AHAA Recap: What Does the Future Hold for American Art History?

PDF: Payer, AHAA Recap

On a sunny afternoon just before the start of the 2024 AHAA conference in Birmingham, Alabama, early arrivers were treated to a tour with the sculptor Joe Minter (fig. 1). Built over more than three decades, “African Village in America” is Minter’s captivating opus. An immersion into a cacophony of improvised sculptures that pay homage to African Diasporic history and the Civil Rights Movement, the tour was a fitting preamble to our three-day program. The symposium that followed offered no shortage of illuminating research, animated debate, and calls to refine our pedagogical approaches. All of this was offered in service of our work in American art; work that as Renée Ater reminded us must “be relevant to the communities we are teaching and living in” during a Saturday afternoon panel.

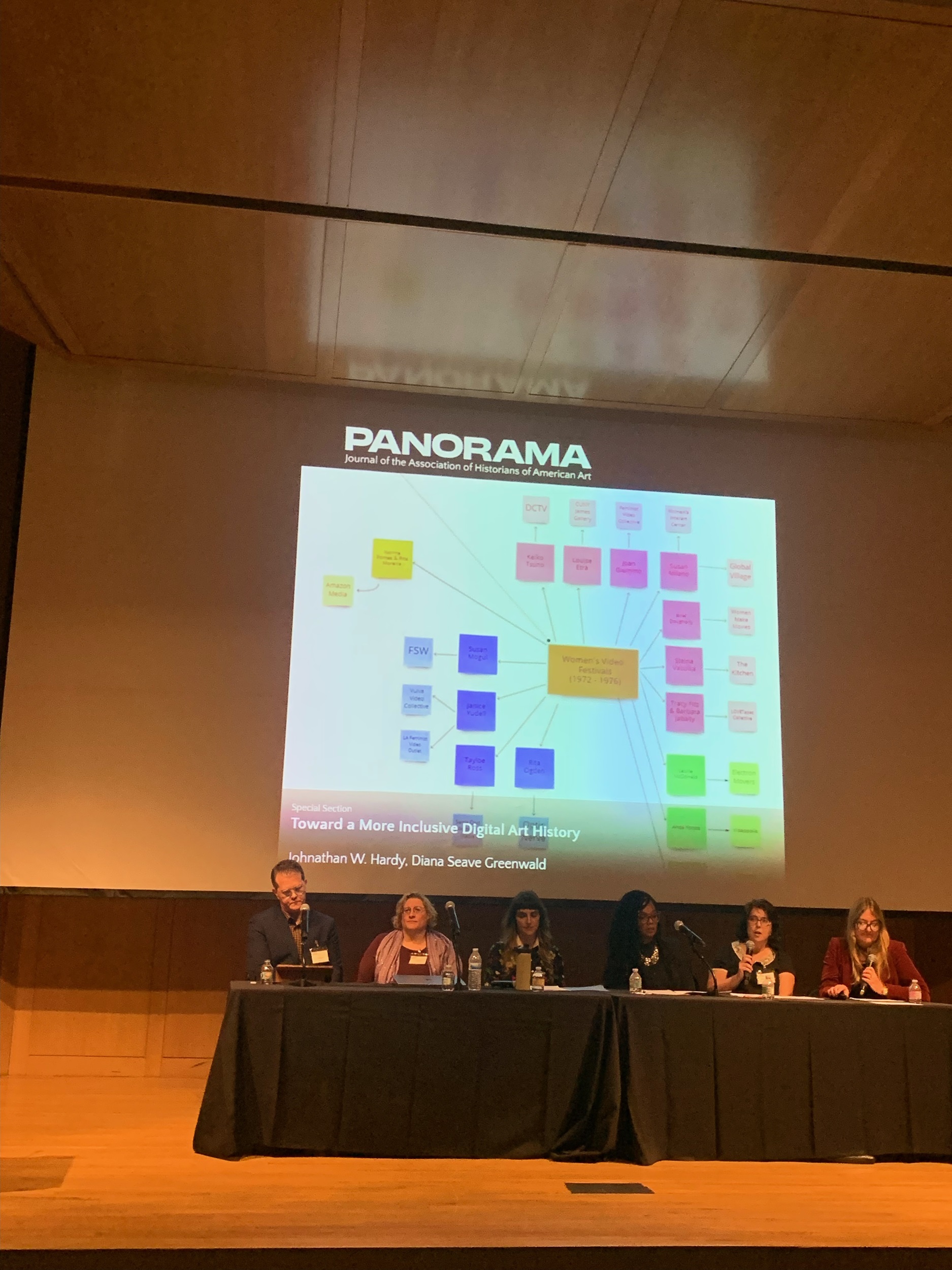

The Thursday evening panel celebrated a decade of Panorama, featuring speakers who took stock of the journal’s numerous contributions to American art scholarship while looking forward to a future that will include a more diverse slate of writers and topics (fig. 2). As the first open-access journal in the field, Panorama embraces digital art history, using new tools that promote quantitative and geospatial methodologies, and has begun to not only measure various metrics of reader engagement but also evaluate the demographics of its contributing writers as a first step in its commitment to greater inclusion of diverse and emerging scholars. A new member of the editorial team, Keidra Daniels Navaroli spoke about the importance of this self-reflective approach to publication infrastructure, which “recognizes that art history is not objective” and that diversity, equity, and inclusion are more than data points and must be about social empathy and care (fig. 3). It is no wonder that Jenni Sorkin, one of the Co-Executive Editors of the journal, found “revision” to be the word most present in a survey of Americanists, the results of which are included in this issue. The questionnaire records, among other things, how our field has benefited from the recent expansion in geographical scope and greater attention to artists of color and Indigenous artists.

Gathered at the Birmingham Museum of Art on Friday, art historians exchanged ideas on meaning, materiality, and the power of place. In the morning, Kimia Shahi examined particulate matter as visual pollution through a look at Kodachrome slides from the EPA’s 1972 project Documerica. Shahi demonstrated how smog became a hypervisible material in Birmingham as ferrous oxide, sulphuric acid, and other emissions from iron and coal plants peppered the air. Aleisha Barton showed how Faith Ringgold’s attention to the materiality of black paint pigments in her Black Light series marked a shift toward situating black as the starting point for all color, thereby moving away from white as origin (fig. 4). I presented a paper considering land, guts, and beads in the work of Nadia Myre and Maureen Gruben and putting Indigenous feminist materiality in conversation with visual sovereignty. In her analysis of Maria Louise Spear’s 1865–67 Memorial Quilt from North Carolina, Elizabeth Keto untangled the textile’s known relationship to the white supremacist project of Confederate memorials and its heretofore unknown link to civil rights activist Pauli Murray’s ancestor. Then, Phoebe Wolfskill showed us how movement, migration, and monumental scale played out in the epic works on paper by Emma Amos with a unique relationship to her birthplace of Atlanta. William Coleman made a convincing case that Betsy James Wyeth was a distinctive designer of architectural and landscape masterworks for which she never claimed credit but are both works of art in their own right and also defined many scenes painted by her husband, Andrew. Louise Siddons wrapped up the morning sessions with a talk on Bean Yazzie, whose photographs of queer Navajo families are deeply informed by place, photographic sovereignty, and culturally specific kinship.

In the afternoon, Molly Eckel read Robert S. Duncanson’s Robbing the Eagle’s Nest as an allegory for abolitionist activism in the wake of Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, tracing its visual elements to depictions of Edom, which abolitionists circulated as a prophecy for the impending doom of a country still practicing enslavement. Emily Burns located Lakota belongings in the paintings of De Cost Smith and Edwin Deming, working toward (re)claiming animate knowledge systems and an interconnected, asymmetrical network of makers. Sehyun Oh carefully situated Kyo Kioke’s Northwest-based photography and botanical practices as a kind of “diasporic imagination” that connected volcanic mountains and related ecologies across the transpacific “Ring of Fire.” Olivia Murphy ended the session with a shoutout to Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter and deeper engagement with April Bey’s multimedia installations featuring Black cowgirls who reimagine the American west outside of this world. The day’s closing session was a workshop led by five industrious organizers who pushed us to rethink the American art survey course by moving toward place-based approaches and using the local as the means with which to do relevant pedagogical work.

Saturday morning brought us to the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where transnationalism, dirt, and a sorely needed discussion about American sculpture were on the docket. In his microhistory of mourning in New Amsterdam, Joseph Zordan narrated how a silver spoon marked grief for the family of Maria Van Rensselaer and was continuously repurposed in estate planning and reinscription by subsequent generations. Hampton Smith centered wrought iron in his study of New Orleans infrastructure, showing how enslaved and free Black craftspeople of Haitian descent made their mark on the ironwork design that bear a visual relationship to Vodou spiritual diagrams known as Vévé as well as culturally significant practices of bundling. Pulling together examples from a few centuries, Smith also brought the relevance of New Orleans blacksmithing to twentieth-century fiction and twenty-first century museums. Sasha Whittaker gave the interwar period its due by carefully looking at the work of Harper’s Bazaar photographers who created images revealing of their hybridized immigrant and American identities. Later that day, Joseph Litts spoke about the grotto as a backdrop for early American portraiture, tactility, and the availability of tourism experiences at many of these sites today. Megan Baker engaged in a process methodology by recounting how she makes pastels herself from historic recipes while discussing how pastels are dangerous to those who make them and experience the workplace hazards of too much chalk dust. Ellery Foutch also engaged a maker’s practice, discussing a chair with turned spindles that she and her students made from an assortment of relic wood as an archive of sorts, once fragmented and now cohesive. Lea Stephenson explored the haptic connection to place through sand, citing Isabella Stewart Gardner’s two etched glass bottles filled with sand collected from Egypt.

The final panel of the conference was a lively roundtable that addressed the imperative to expand the field of American sculpture and better engage the public. Renée Ater, Kelvin Parnell, and Brittany Webb traded beautiful oration and incisive critiques back and forth as the symposium came to a close. We heard about the first retrospective exhibition of the twentieth-century sculptor John Rhoden and his sensuous work influenced by love, travel, and remarkable determination. In contrast, we heard about the monuments in the United States that have so often failed, left out, or stereotyped Black artists and community members. Quite clearly, we heard Kelvin Parnell’s provocation: “We should ask ourselves, what is the role of scholarship on sculpture in impacting real people and communities?” Indeed, how does our work serve others? These were examples of the “honest conversations” that our panelists both demonstrated and called for in American art; conversations that reverberated throughout our conference and will continue to unsettle the field.

November 22, 2024: This article was updated to correct the spelling of Maria Louise Spear’s name and the date of her Memorial Quilt.

Cite this article: Taylor Rose Payer, “AHAA Recap: What Does the Future Hold for American Art History?” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 2 (Fall 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19460.

About the Author(s): Taylor Rose Payer is a PhD candidate and a teaching fellow in art history and American Indian studies at the University of Minnesota.