A Look Back: Thirty Years of AmArt-L

In fall 1994, two graduate students—one at Santa Clara University in California and the other at the City University of New York (CUNY)—had a then-revolutionary idea: to connect scholars of American art through the comparatively new medium of online communication. At the time, Andrea Pappas and Sue Luftschein wanted to confront the relative invisibility of American art within the growing network of art historians on the World Wide Web. Over the course of a year, they worked to develop and launch the American Art Listserv (AmArt-L)—a platform that not only charted a course for new and emerging scholarship but also cultivated a network of connection, community, and visibility. In celebration of the listserv’s thirtieth anniversary, this essay traces the history of AmArt-L, visualizing key moments as well as the noteworthy contributions of its subscribers to the field’s scholarship.

Today, online communication is ubiquitous, but in the early 1990s, internet usage was markedly different. Prior to the proliferation of Web 2.0 and the popularity of user-generated content, the Internet was not only a space limited to specialized spheres of research and computational expertise, but it also was dominated by men and the gendered stereotypes associated with technological innovation and entrepreneurship. Listserv programs—file server–supported networks that utilize emails for mass communication—developed in response to a growing network of communities of practice.1 As a relatively new technology, developed less than ten years before the creation of AmArt-L, listservs offered Pappas and Luftschein innovative possibilities and unique challenges.

In addition to the intricacies of command-input coding, one of the most critical challenges in the development of AmArt-L was finding an institution with the ability to store the listserv’s data files. Luftschein, with the aid of her dissertation adviser, Sally Webster, was able to proffer server access at CUNY (one of the earliest pioneers in academic computing networks). CUNY’s willingness to host the listserv represents a significant investment of resources in AmArt-L. Pappas’s prior experience in computer programming was crucial to meeting the listserv’s technical demands as well as setting its standards for online interactions. For Luftschein and Pappas, AmArt-L offered a promising new platform for the dissemination of information among emerging and established scholars. “We wanted to get people ‘in the room’ so that they could be present in the discourse,” Pappas explains, “We wanted to provide a space for professionalization, but the first aim was connection.”2

Their goal was met. Within the first week of its launch, AmArt-L attracted more than two hundred subscribers—a significant feat at a time when many seasoned art historians lacked email addresses. Clearly, a larger community of students and young faculty longed for the same opportunities Pappas and Luftschein sought. As one early user noted, “I wish there were more art history connections as many of us work not only in the North American geographic area, but in others as well.”3 The ability to connect across geographic space provided an unprecedented opportunity for access and inclusivity within the field and strengthened the impact of professional development organizations, like the Association of Historians of American Art (AHAA) and the College Art Association (CAA). Notably, Pappas and Luftschein successfully lobbied through AmArt-L that AHAA become an affiliate member of CAA—a crucial step in expanding AHAA’s membership and garnering recognition for Americanists worldwide.

As AmArt-L grew, so did its areas of specialization, which eventually extended beyond the boundaries of art history to include American studies, museum studies, history, cinema, popular culture, and architecture. In 2007, the listserv was transferred to Florida State University, where Karen Bearor, an early subscriber to AmArt-L, took over the responsibility of moderating the discussion posts of an estimated five hundred subscribers. As of March 2024, AmArt-L had 1,270 subscribers, representing a growth of 535 percent since its inception. What began as an experiment for two burgeoning scholars working hundreds of miles apart set a precedent for online communication that has persisted for decades.

Visualizing the AmArt-L Archive

Although there are always limits to painting a comprehensive picture with data, the archives of AmArt-L provide a wealth of information about US art and the research interests of Americanists over time. Inspired by these possibilities, and in my new role as the DEI/DAH (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion/Digital Art History) manager for Panorama, I initiated text-based data analyses of the listserv’s discussion posts in summer 2024.4 Looking at posts from November 1994 to March 2024, I considered several questions: How has AmArt-L supported the study of American art and visual culture? What are some of the key issues, concerns, and opportunities driving listserv exchanges? Finally, how can AmArt-L’s impact be visualized?

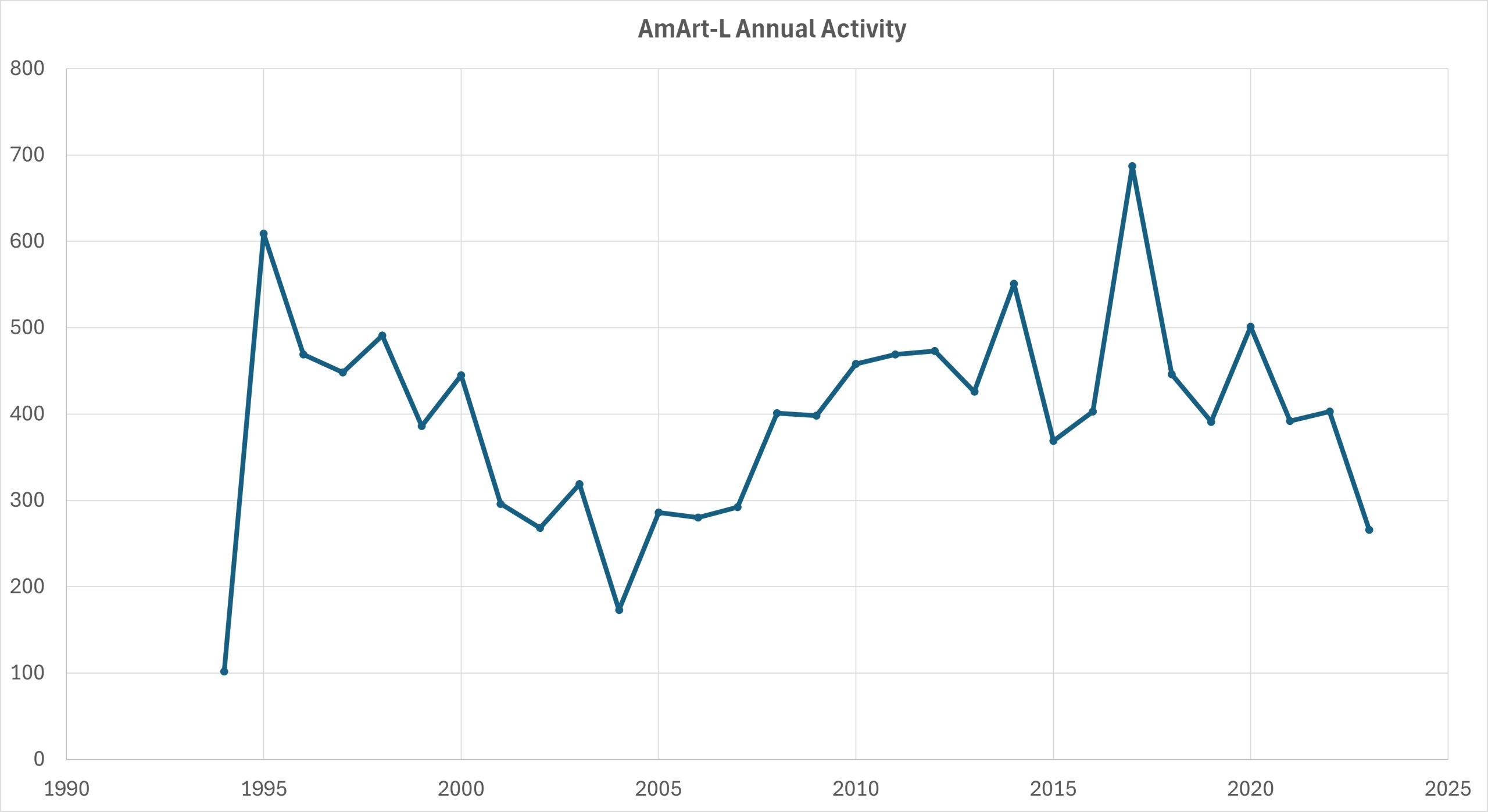

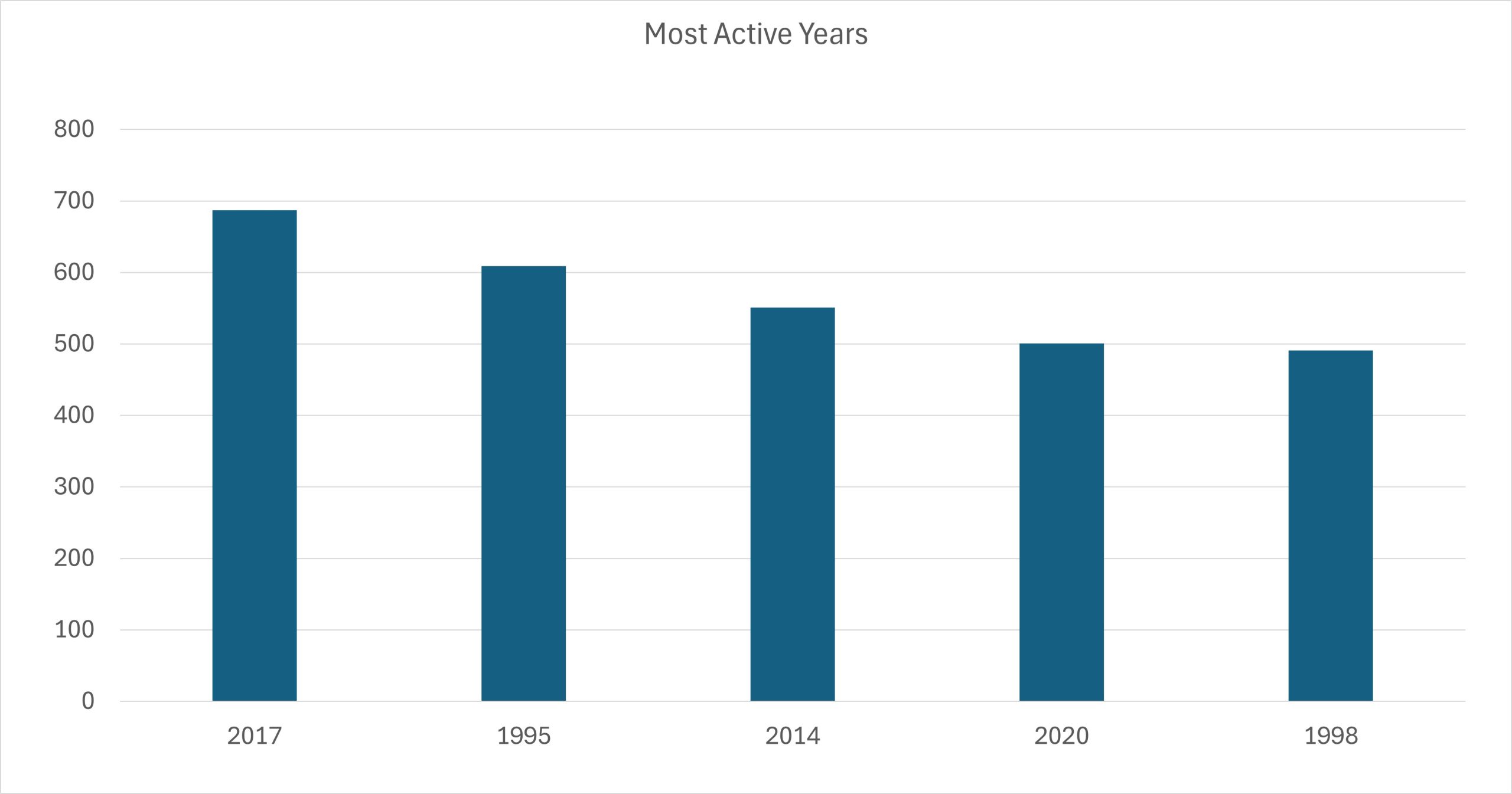

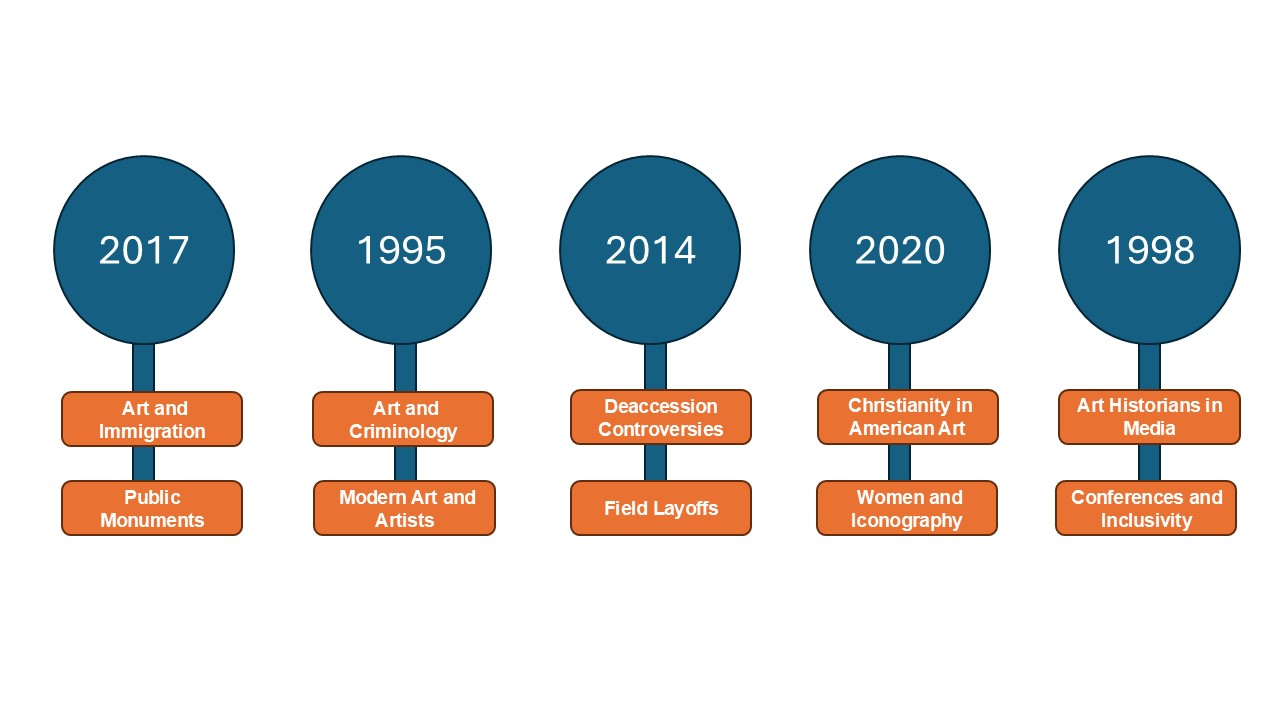

Measuring listserv posts over time (fig. 1), I was able to isolate notable periods of activity. As figure 2 illustrates, the most active years for listserv participation (in descending order) were 2017, 1995, 2014, 2020, and 1998. Conversations during these years centered on a variety of concerns and inquiries (fig. 3). In 2017, for example, subscribers engaged most with two critical topics: 1) immigration and the art world—a response to federal legislation banning the immigration of citizens from select majority-Muslim countries—and 2) the destruction of public monuments in light of the nationwide protests against Confederate monuments. In these discussions, members challenged the role and purpose of AmArt-L in times of political divisiveness, cementing AmArt-L’s value as a resource, a community, and a form of user-driven activism.

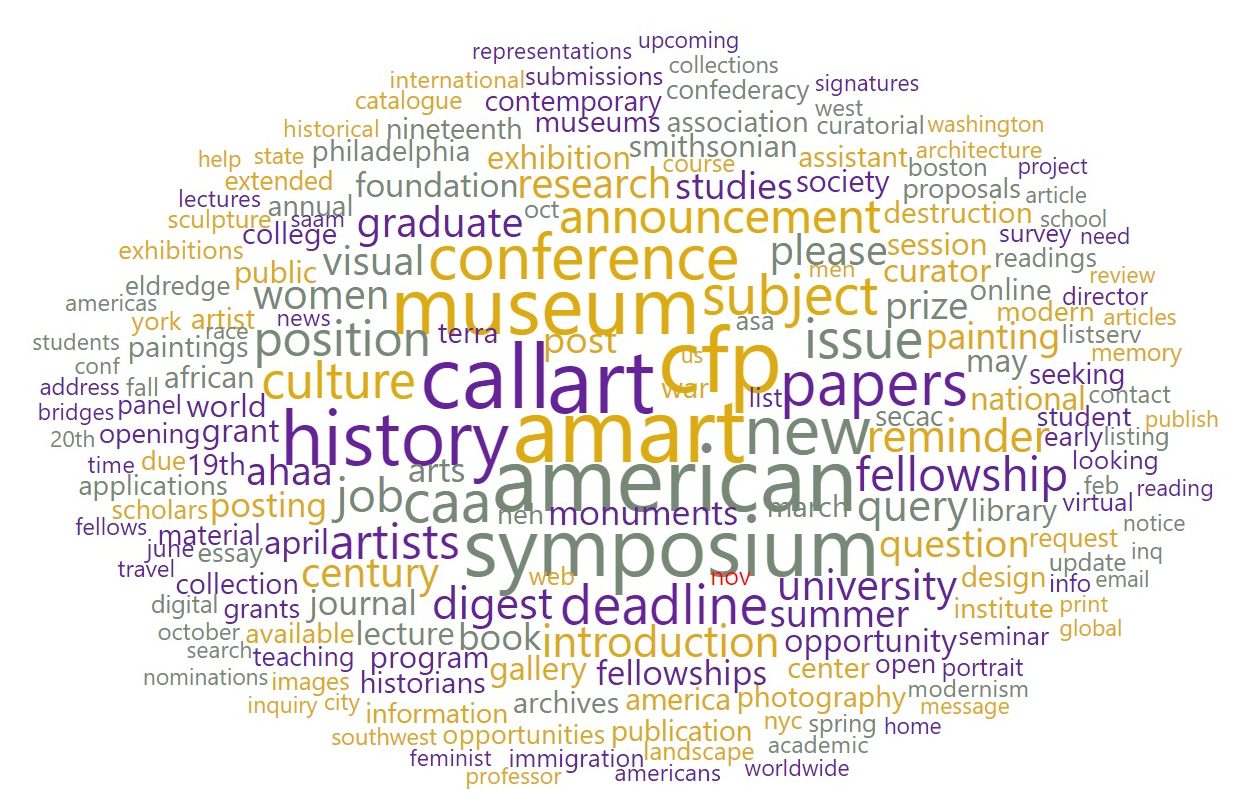

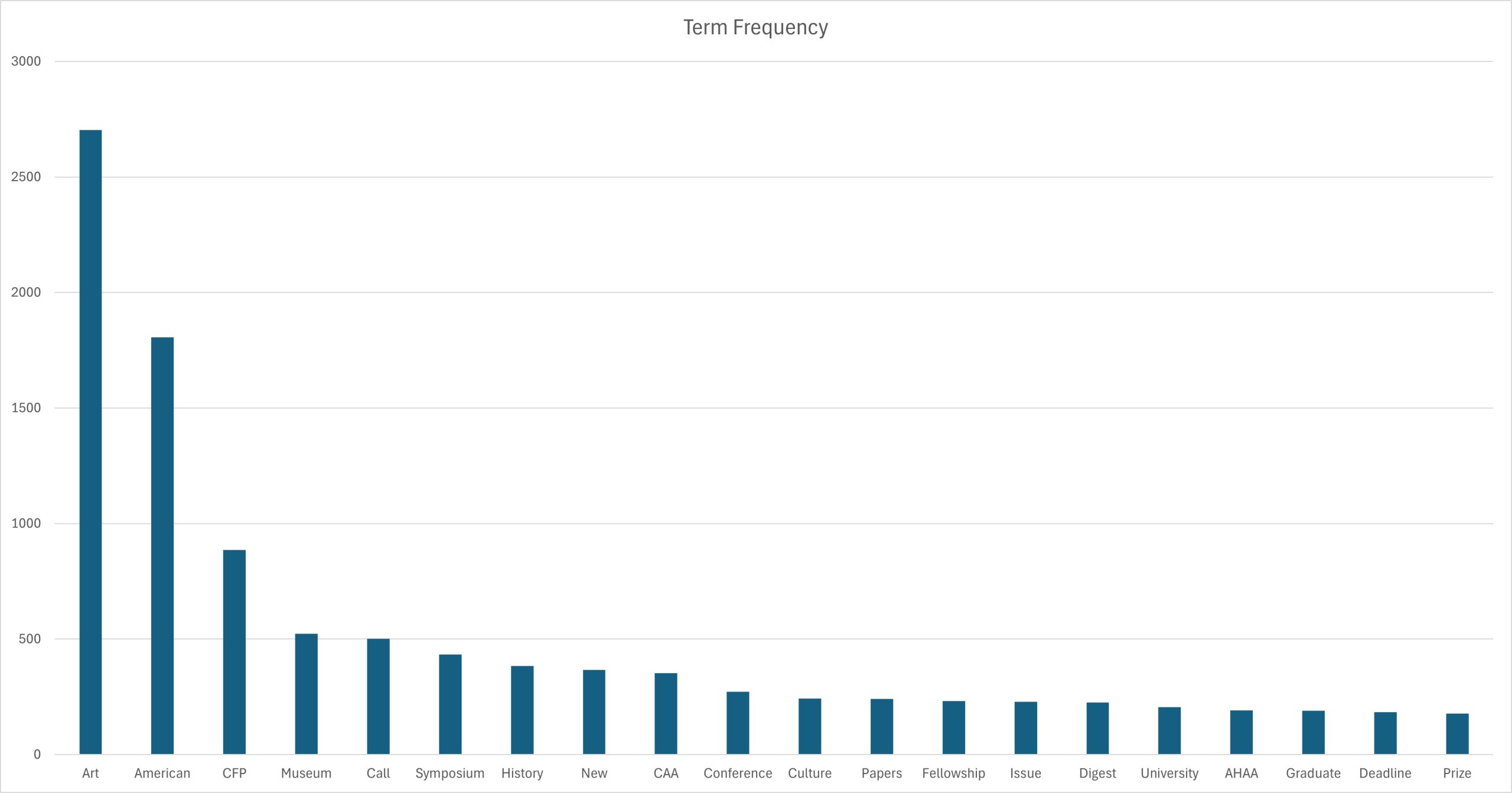

Analyses of email subject lines sent since 1994 reveal what subscribers talked about most often. A word cloud (fig. 4) illustrates popular terms by prominence, and a corresponding bar graph highlights the top twenty terms and their recurrence (fig. 5). As expected, given the listserv’s focus, the words “American” and “art” appear the most often, and in line with the previously mentioned popular topics, “war,” “destruction,” “monuments,” and “confederacy” also appear repeatedly. Other prominent terms, including “call for proposals (CFP),” “symposium,” “fellowship,” and “conference,” reflect the use of AmArt-L for networking and professional development.

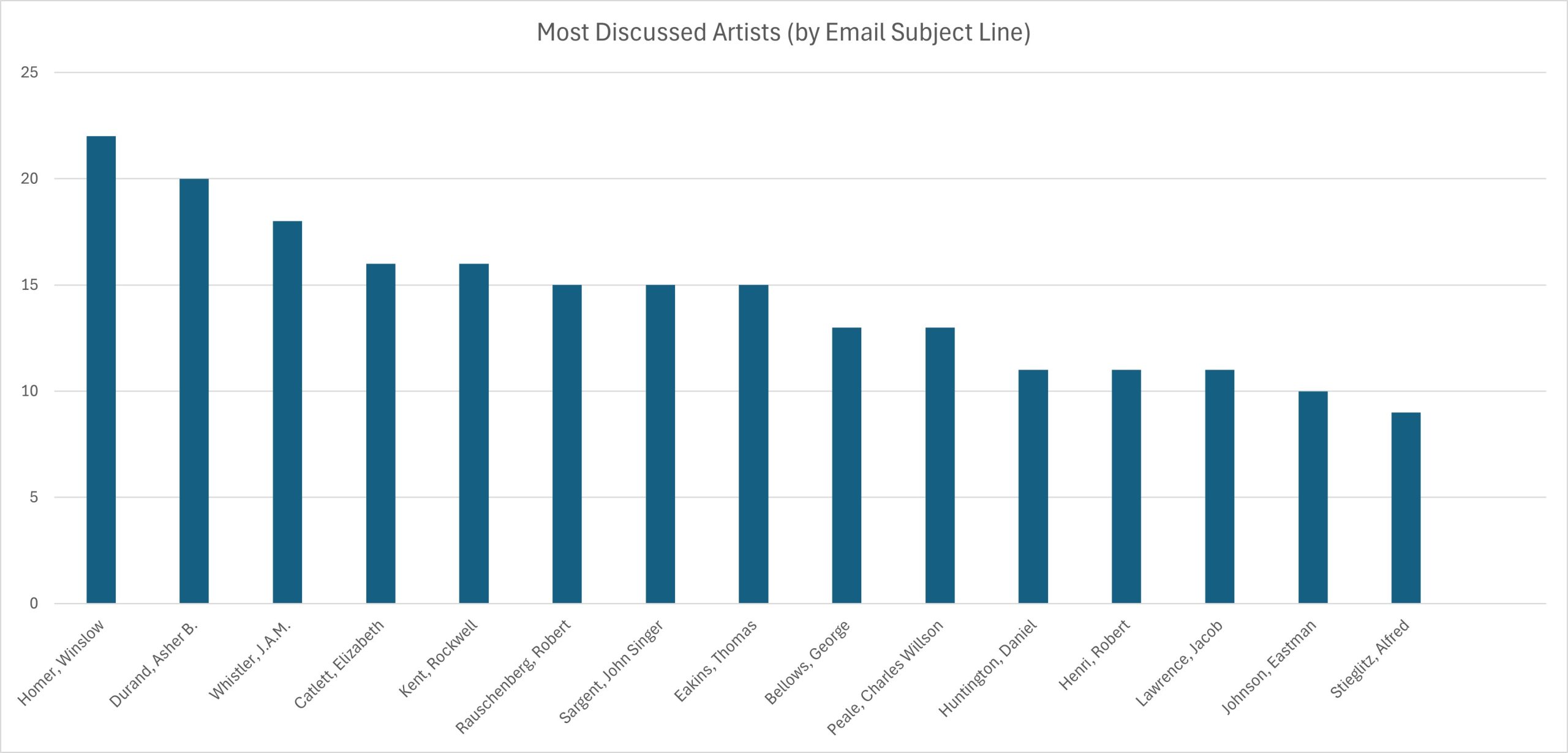

As suggested by the most popular terms, subscribers to AmArt-L tend to engage with broader themes and topics within American art. Over the years, email subject lines related to specific artists have been limited. Nevertheless, some patterns and visualizations can be gleaned from the data provided. Figure 6 presents a graph of the top fifteen artists mentioned in the listserv’s email subject lines.5 Winslow Homer led these discussions with twenty-two posts. Most of these inquiries were focused on his representation of gender, race, and nature, as well as recommendations for new scholarship. Homer-related exchanges are spread out over time with clusters of conversations occurring in 1995, 2011, and 2014. Other artists of note include African American artist Elizabeth Catlett—the sole woman represented in the featured graph. Her 2012 death garnered tribute posts, and in 2022, subscribers used AmArt-L to find resources for the exhibition of her early works in painting and sculpture. While at first glance, names such as Homer, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, John Singer Sargent, and Thomas Eakins may suggest some lingering conservatism within the field, it is important to emphasize the comparatively small sample size of these conversations. Homer may have the highest frequency, but he represents a mere .2 percent of AmArt-L’s dialogues.

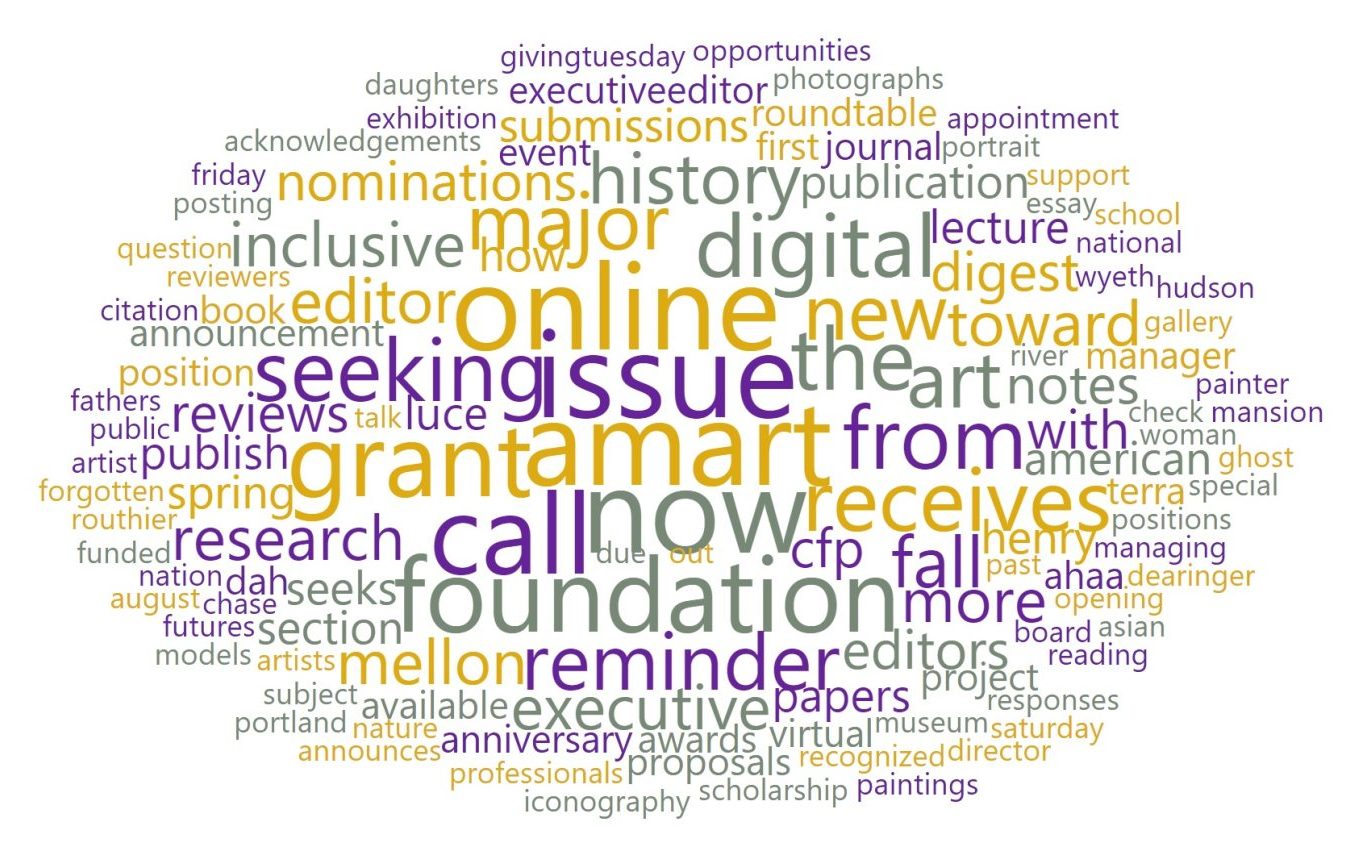

AmArt-L has been repeatedly used as a platform to ask larger questions about the limits and biases of the field. In both 1996 and 2008, for example, questions about the “Americanness of American art” and “American icons” not only served to address who the discipline represents but, more critically, who it leaves out. The recurrence of words like “African,” “feminist,” and “race,” among other terms, coincides with such inquiries. Responsively, Panorama debuted on AmArt-L in 2013 with a CFP for its inaugural issue, which encouraged perspectives that applied “local,” “global,” and “interdisciplinary” contexts to the study of American art and visual culture. A word cloud of Panorama’s posts to AmArt-L (fig. 7) illustrates the journal’s most frequently used terms—many of which correspond to words mined from AmArt-L’s larger archive. Each year since Panorama’s fall 2014 debut, AmArt-L has served as a resource for the journal’s promotion of art-historical scholarship.

Conclusion (and Considerations)

A closer look at AmArt-L reveals a story of experimentation, activism, and critical engagement. Today, the ephemeral nature of online communication and the rapidly changing preferences for digital technologies can obscure the histories (and individuals) vital to a digital community’s development. Pappas and Luftschein created AmArt-L in a digital landscape that was limited in its accessibility—especially for young female scholars. More than thirty years later, the impact of AmArt-L is reflected not only in its creators’ willingness to experiment with innovative technologies but also in a growing network of subscribers committed to fieldwide change. Documenting the listserv’s history, even in part, offers opportunities for the preservation and assessment of user-sustained technologies. Although the migration of AmArt-L’s archive is in transition, the listserv itself recently moved to AmArt Google Groups, which can be accessed by emailing Amart-l@barnard.edu.6

AmArt-L has been maintained by a network of volunteer labor and supported by the allocation of educational resources. Its archives are living records, which—through computational analyses, such as machine learning and data mining—provide options for quantifying the community’s growth as well as its areas of neglect. Accessing the AmArt-L archive is critical not only to understanding a process of evaluation and change but also to ensuring its community maximizes opportunities for access, inclusion, and responsibility.

Cite this article: Keidra Daniels Navaroli, “A Look Back: Thirty Years of AmArt-L,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 2 (Fall 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19437.

Notes

This research was conducted with the technical support of Brook Miller at the University of Central Florida’s Center for Humanities and Digital Research (CHDR). Additional thanks to Andrea Pappas and Sue Luftschein for generously sharing their insights and experiences and to Florida State University for providing access to AmArt-L data.

- Listserv software was developed in the mid-1980s by École Centrale Paris graduate student Éric Thomas. See D. A. Grier and M. Campbell, “A Social History of Bitnet and Listserv, 1985-1991,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 22, no. 2 (2000): 32–41, https://doi.org/10.1109/85.841135. ↵

- Andrea Pappas, in discussion with the author, August 22, 2024. ↵

- Joan M. Vastokas, “Meet Your Moderators” AmArt-L, November 15, 1994, 18:50:28 EST. ↵

- For this research, data was mined from approximately 12,210 email posts archived over a thirty-year period by Florida State University. Data was extracted from archived hypertext markup language (html) files using a custom Python script, converted into comma-separated values (csv) files, and processed for visualization. The infographics featured were generated through a combination of Microsoft Excel and PowerPoint software and the open-source data-mining program Orange. ↵

- In order to distill a list of popular artists, listserv terms were organized and isolated by frequency. A total of 9,697 terms were filtered to account for last names appearing with a recurrence of ten or more posts. These names were reviewed and cross checked with email topics from a corpus of 12,210 posts to distill a final list and eliminate irrelevant data points. Only inquiries related to an artist, their body of work, exhibitions, symposia themes, or call for proposals were counted. Museums, foundations, or scholarships named for specific artists were excluded. ↵

- The AmArt Google Group is moderated by Elizabeth Hutchinson, associate professor of American art history at Barnard College and member of Panorama’s Advisory Council. ↵

About the Author(s): Keidra Daniels Navaroli is a McKnight Doctoral Fellow at the University of Central Florida and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion/ Digital Art History Manager at Panorama.