A Trail of Coins from Yemen to New York: Pirates, Plunder, and Enslavement in the World of Margrieta van Varick, ca. 1695

PDF: Um, Trail of Coins

Author’s Note: This essay is accompanied by an interactive map (https://indianoceanexchanges.com/coin/mvvmap.html) that will assist the reader in locating key sites, dispersed across four continents and two major bodies of water. The text prompts readers to find and explore the sites based on color, enabled by a color library selected for its visual accessibility. Purple markers indicate where Yemeni coins have been located in North America and off the eastern coast of Africa; teal markers indicate key Arabian Peninsula and Indian Ocean locations stretching from the Red Sea to Southeast Asia and the Cape of Good Hope; and yellow markers refer to places that are relevant to the life of Margrieta van Varick, which span the entire breadth of the map.

Introduction

In a recent issue of the journal Art History that treated the visual and material culture of the “vast early modern Atlantic,” coins make several prominent appearances among a range of other forms. In the volume’s introduction, the co-editors, Esther Chadwick and Cécile Fromont, show how a group of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Caribbean coins were significantly modified through punching, clipping, and overstamping, interventions that vividly attest to the fragile British attempt to consolidate economic control over Spanish-ruled Dominica.1 In her own essay in the volume, Chadwick explores a coin type from Haiti known as the “One Gourde,” which both enshrined and overwrote longstanding conventions of European coins and medals by featuring a prominent profile image of Henri Christophe, the Black king who adopted post-revolutionary power on that island in 1811.2

Drawing attention to an enduring limitation in the field, Chadwick boldly declares that “numismatic objects give distinctive material form to the historical complexities of power, value and representation in the Atlantic world. Accordingly, they are worthwhile as subjects not just of antiquarian but of art-historical study.”3 Chadwick’s pronouncement points to the ways that art historians tend to restrict the interpretive scope of coins, targeting them instrumentally as mere markers of chronology or as empirical indices of iconographic change. On the same topic, Laura Kalba has pressed even further, calling into question art historians’ “hardwired antipathy toward numismatic subjects.”4

This essay takes inspiration from these provocations to center coins within art-historical analyses. It also amplifies Chadwick’s pointed contention that coins are material instruments of exchange that traverse economic systems and can thus unlock the understanding of a whole host of complex early modern oceanic relationships both within and outside of the Atlantic world. Ultimately, this study is grounded in the simple premise that a woman named Margrieta van Varick held some silver coins from Yemen in her estate, among countless other items, at the time of her death in the year 1695. This basic contention, which builds on new archaeological evidence, is both unexpected and powerful, in that these coins wholly pivot our lens on Margrieta’s biography, which, in previous scholarship, has been oriented primarily around her role as a wife and mother.5

When spotlighted, these coins—modest in size, epigraphic in design, and excavated in sites far from their place of origin—speak loudly, prompting us to follow their distinctive peregrinations from the coast of the Arabian Peninsula to the southern islands of the Indian Ocean, and finally to the Atlantic seaboard of colonial North America. As such, they decidedly redirect our attention toward Margrieta’s role as a businesswoman and an enslaver during a fleeting period of time when New York City was directly connected to the Indian Ocean and deeply involved in the Madagascar slave trade. This shift, then, calls for speculation on the occluded biography of a woman named Bette, whose life story has been tethered to that of her enslaver. Ultimately, this interpretation reveals how far-flung matrices of maritime violence and enslavement facilitated the consumption of Indian Ocean goods in late seventeenth-century colonial New York.

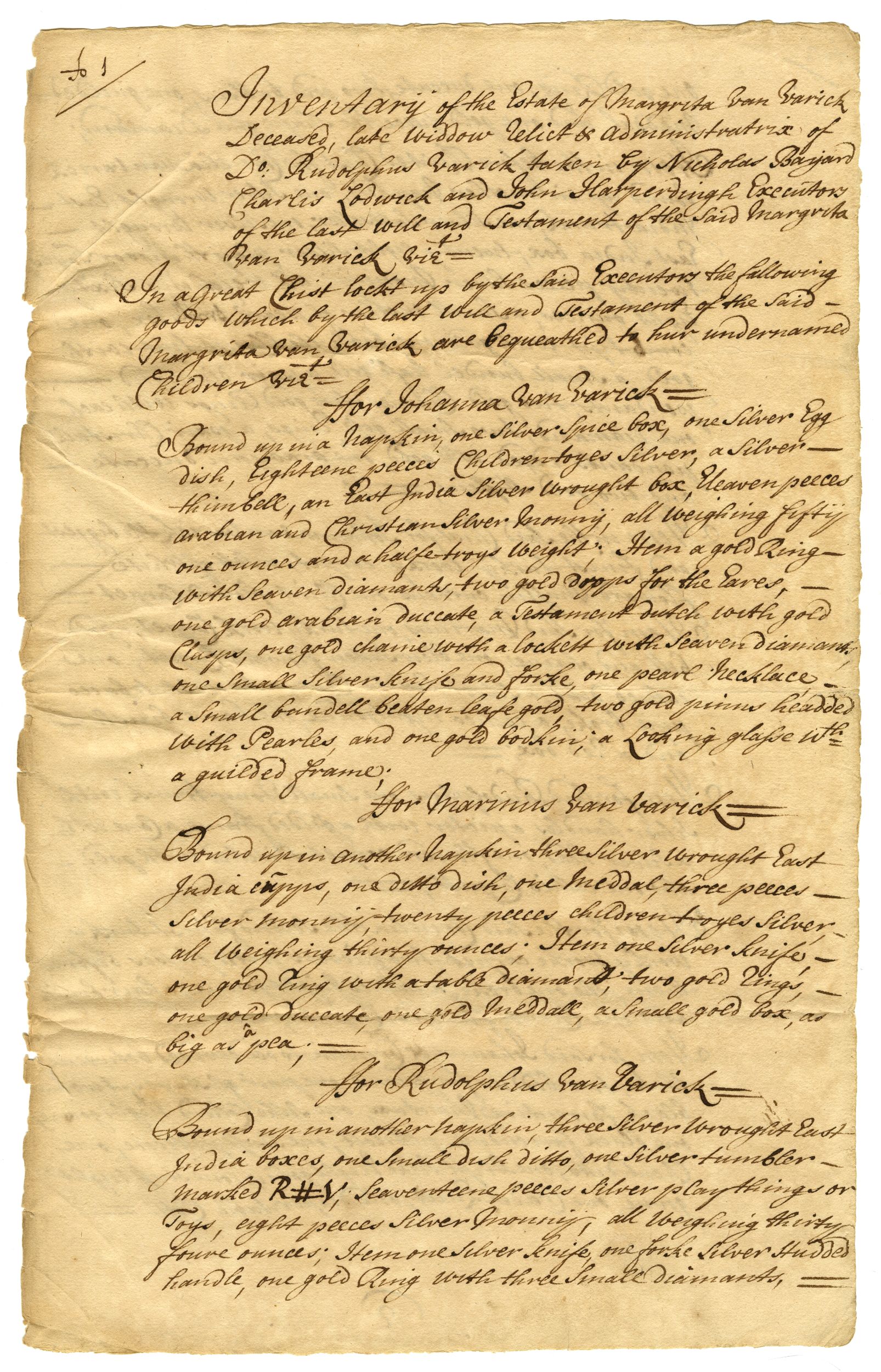

The Inventory of Margrieta van Varick

Margrieta van Varick (d. 1695) is known to us today primarily through a copy of her inventory, held by the New York State Archives. Numbering eighteen pages and completed by three assessors on May 29, 1696, it lists her household possessions as well as those that remained in stock at the small shop she kept at the time of her death. She was born in Amsterdam in 1649 and then moved to Malacca, a major trade entrepôt in modern-day Malaysia, before she turned twenty (see map). She married in Malacca but then returned to the Dutch Republic after her first husband, a merchant, died. There she married for the second time and then traveled with her family across the Atlantic to New York in 1686. She settled in Flatbush, one of the five towns colonized by the Dutch on Long Island, where her husband was appointed as a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church (see map).6 She lived there until her death in 1695. While overseas travel was not entirely unusual for women in the Dutch Republic during this booming maritime era, very few women had the opportunity to cross both the Indian and Atlantic Oceans.7 Among them, Margrieta is unique in that her inventory has survived over the centuries and can serve as a materially salient window into her biography.

This interactive map (https://indianoceanexchanges.com/coin/mvvmap.html) will assist the reader in locating key sites. Hover over the color-coded markers for labels and click on them for additional information, images, and links for further reading. The recenter icon located in the upper left corner resets the map’s zoom level to its default. This map is best viewed and navigated on a desktop or laptop computer rather than a mobile device.

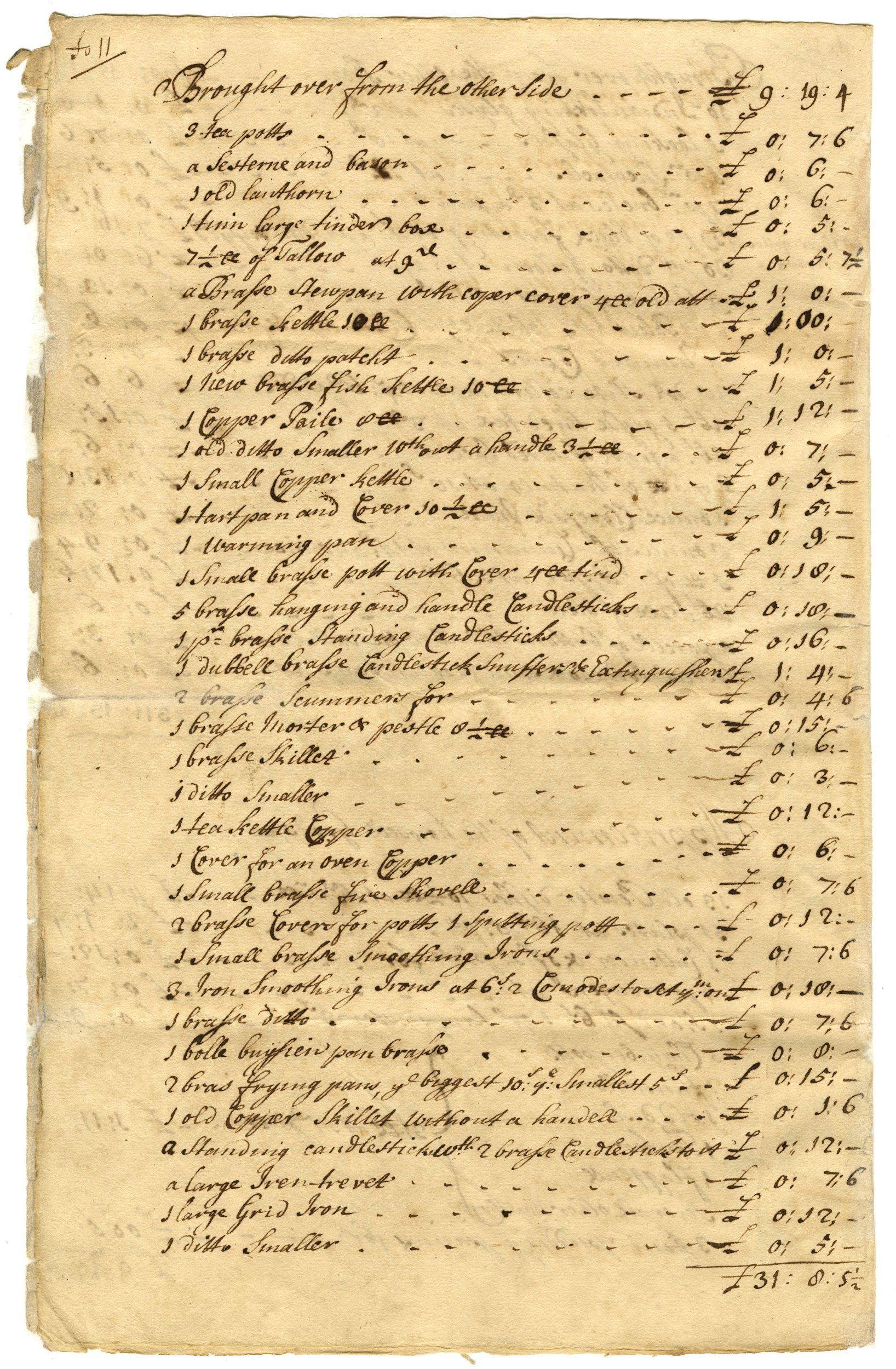

Among the long list of Margrieta’s possessions, we find expected household items, such as those that filled her kitchen: kettles, skillets, pans, dining utensils, porcelain vessels, and more (fig. 1). The inventory also contains the accessories of motherhood, such as baby’s caps, bibs, diapers, and toys. (She was survived by four children, ages two through thirteen at the time of her death.) Clothing and textiles also figure prominently on the list, both as yardage and as garments crafted of damask, serge, flannel, linen, calico, crepe, and other types; some of these she acquired for resale in her shop. Numerous items that may have held personal value, such as “a gold Ring—with seaven diamants,” “an East India Cabinet with an Ebony foot wrought,” and “the picter of Mrs Varick,” were expressly set aside for her children, while the rest of the estate was to be sold off, with the proceeds also going to her children.8

Some of these items are described with precious details that invite comparison to specimens in museum collections today, such as the aforementioned cabinet of tropical wood raised on feet of ebony (fig. 2). Even though none of the descriptions can be associated confidently with known objects, it is clear that some were procured from afar. Indeed, some items are labeled in terms that point directly to distant geographies, such as “Jappan boxes” and “China Cupps with Covers.” As a group, these objects evoke a late seventeenth-century world of consumption provisioned by networks of trade that stretched to the Middle East and Asia, offering painted cottons from India, Chinese porcelain wares of many types, Middle Eastern carpets, and items hewn from Asian hardwoods, among other goods. Caroline Frank posits that the presence of goods from China in colonial North America is evidence of an “indirect” relationship of exchange, both intellectual and material, between the two regions that existed before American independence.9 Margrieta’s inventory represents the wider material aspirations of the moment, with its array of items that were valued for their visual and tactile appeal, their innovative production technologies, and undoubtedly their perceived exotic uniqueness.

The inventory was featured as the centerpiece of a sumptuous exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, New York, in 2009. This show, which was groundbreaking in presenting the first comprehensive body of research on Margrieta and her estate, offers the prevailing assumption that her time spent in Asia, as well as her two husbands’ stints there, allowed her ready access to these goods, procured before they moved to New York (fig. 3). Namely, catalogue contributor Ruth Piwonka found the contents of Margrieta’s inventory, with its large quantity of high-quality wares from afar, to be unique in comparison to those of other New York women of similar status from the same era. This difference led her to posit that the foreign goods Margrieta owned were meaningful to her personally, based on her own travels in the East and those of her first and second husbands, both of whom had served the Dutch East India Company.10 The exhibition co-curator Marybeth De Filippis echoed that perspective, writing, “Margrieta’s first husband, Egbert van Duins, participated in this Indian-Malaccan trade, a connection that perhaps explains the presence of some of the Eastern goods on Margrieta’s inventory.”11 In this way, Margrieta’s personal narrative and travels have greatly underpinned our contemporary understanding of her estate holdings.12

Here I suggest an alternate mode by which these goods entered Margrieta’s possession, contending that at least some were accumulated after her arrival in New York, for retail purposes and for personal use. During the 1690s, New York City, which was in close proximity to her home in Flatbush, served as a key entrepôt for goods acquired directly from Indian Ocean channels. This maritime path constituted an alternate route to the prevailing trading circuits that radiated from Europe and were sustained by the charter trading companies: the English East India Company, the West India Company, and the Dutch East India Company. Indeed, at this time, New York merchants engaged directly with Anglo-American pirates, and together the two groups trafficked enslaved people from Africa, working outside of the charter company circuits. Concurrently, New York officials sponsored privateering while also turning a blind eye to piracy, although the lines between the two domains could be traversed easily at a time when conceptions of maritime imperial sovereignty were being vetted hotly on the opposite shore of the Atlantic. As historian Robert Ritchie describes, “New York became notorious as a pirate haven and the center for supplying the Indian Ocean pirates.”13 These conditions served as more than a contested backdrop to Margrieta’s life in Flatbush. Margrieta herself was imbricated in these circuits of transoceanic exchange, as a shopowner but also an enslaver. The coins she held at the time of her death provide the most vivid material means to understand this involvement, while also prompting a return to the biography of Bette, the enslaved woman that is mentioned only briefly in Margrieta’s will.

The Arabian Chequin

Coins appear in multiple places in the inventory, including several that are singled out in its first pages as items expressly set aside for her children. To her son Marinus, Margrieta left “one gold duccate.” To her younger son, Rudolphus, she also left “one duccate,” but without specification of its metal content. One can presume that both coins were minted on the model of the Venetian gold zecchino, or ducat, a denomination that weighed 3.5 grams and measured around 20 millimeters in diameter (fig. 4). The Venetian ducat became a prevailing currency in the sixteenth century and was imitated across Europe and the Middle East. Its size and weight came to constitute an early modern transregional monetary standard over both land and sea routes. While we can ascertain the size and weight of the two coins due to the stated denomination, it is impossible to know where they would have been minted. The ducat and its derivatives were produced in many locations outside of Venice in the seventeenth century.14

Another gold coin in the inventory, meant for Margrieta’s elder daughter, Johanna, was described with more precision as “one gold arabian duccate” (fig. 5). A subsequent paragraph mentions a seemingly similar type: “one arabyan duccate” for Cornelia, her youngest child. In contrast to the ducats earmarked for Marinus and Rudolphus, which cannot be associated with mint sites, these two “Arabian” coins, both intended for Margrieta’s daughters, can be located with more confidence. They were likely minted by the Ottomans, or perhaps the Safavids, on the Venetian standard of the ducat. While the Ottoman altin or sultani and the Safavid ashrafi were of the same size and weight as their Venetian counterpart, each was covered with epigraphy in Arabic script and interspersed with decorative motifs, rather than bearing figural imagery (figs. 6 and 7).

In this context, the term “Arabian” should not be understood as a precise reference to the geographic region of the Arabian Peninsula or even to today’s broader Arab world. Neither Margrieta nor those who assessed her estate would have been able to read the coins’ inscriptions to determine where they had been minted. Nor would they have been aware of the distinctions between the various languages written in Arabic script, such as the Ottoman Turkish or Persian writing that would have been featured on these coins. I propose that the term “Arabian” was deployed in this context in reference to the presence of Arabic script, as an epigraphic way of pointing toward the wider Islamic world, rather than delineating a specific or known geographic location. It is also possible that the unspecified ducats intended for Marinus and Rudolphus fell into the same category, even though they are not referred to by the term “Arabian.”

So, why, then, would Margrieta hold two, or perhaps even three or four, gold coins minted in the Ottoman or Safavid world at the time of her death? To answer this question, one must turn to the history of coinage in the North American colonies in the late seventeenth century, which was characterized by a persistent lack of specie. There were no active mints in North America in 1695. The Massachusetts Bay Colony mint, which had issued low-denomination silver coins for a few decades, shuttered in 1682 (fig. 8).15 Additionally, England severely restricted exports of sterling to the colonies. Thus, without a dominant currency, colonial Americans had to rely on a panoply of foreign coins, in gold, silver, and copper, to conduct their business, in addition to engaging in barter, using bills of exchange, and eventually relying on paper money.16

![Silver coin with a spiky tree in its center, surrounded by a circle of dots. Around the edge of the coin are the letters "S A T H U S E [I or T] S • IN •](https://journalpanorama.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/word-image-20342-9.jpeg)

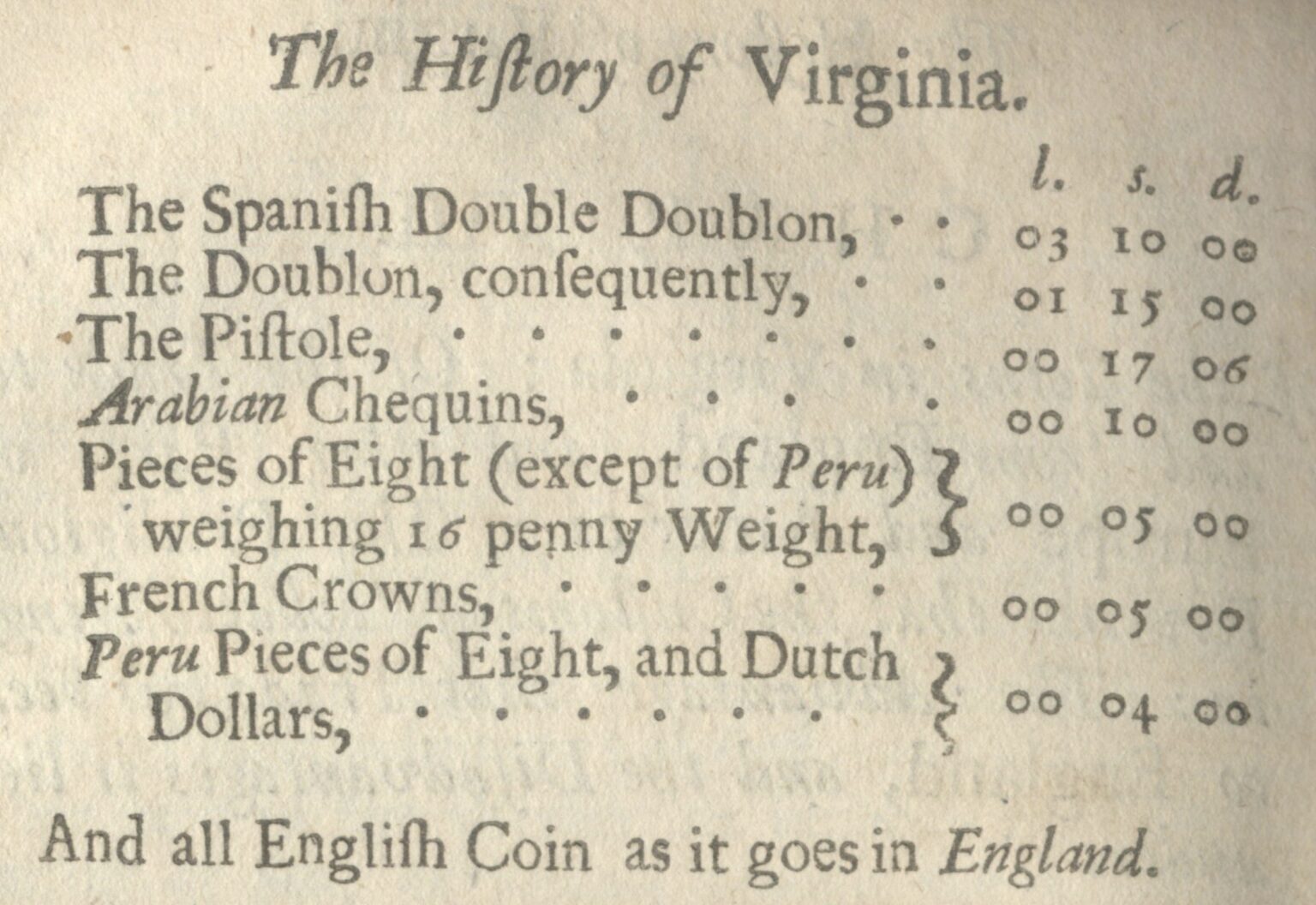

It is not so surprising, then, that the Ottoman altin or the Safavid ashrafi found a useful place in colonial America, with its multiplicity of currencies. Numismatic historian Oliver Hoover notes, however, that the circulation of Islamic coins in the colonies “has been so thoroughly forgotten that only a very few are probably aware that it ever existed.”20 A historical account published in 1708 listed the range of foreign coins in circulation in Virginia at that time, thirteen years after Margrieta’s death (fig. 9). Notably, the Arabian ducat appears here as well, referred to by a cognate term, the Arabian chequin.21 This foreign currency appears on this list without any gloss or description, suggesting not only that it was exchanged with a frequency that merited its inclusion but also that it was recognizable enough to be noted without further elucidation. Yet, even if it was a known currency in Virginia, it did not circulate widely there or in New York.22

Hoover cites various possible channels of conveyance for these gold Arabian chequins to colonial North America, including both Mediterranean and Indian Ocean routes. While these gold coins appear in late seventeenth-century and early eighteenth-century local textual sources, including those mentioned above, there are no extant specimens that are known to have circulated in colonial North America. According to Hoover, “they now seem to have completely disappeared from the North American find record.”23 As is common with any item of gold, the raw material would have been avidly repurposed, so the lack of material evidence should not be taken as indicative of this coin’s historic reach or scope.

Arabian Silver Money

In addition to these four gold coins, a total of forty-two silver coins are included in Margrieta’s inventory, also set aside expressly for her children. As with their gold counterparts, the silver coins are invoked with varying degrees of specificity, although they are never named by denomination. Here as well, some of the silver coins came from the Islamic world, particularly those described as “eleaven pecces Arabian and Christian silver monny” that were earmarked for Margrieta’s elder daughter, Johanna (see fig. 5).

The curators of the 2009 Bard exhibition surmised that the coins described as “Christian” were Spanish reales, minted under Iberian authority of silver mined from Potosí, in present-day Bolivia. Although these Spanish reales were issued in various denominations, the most important and widely circulating was the Spanish real of eight, often referred to as the Spanish dollar or piece of eight (fig. 10). A hefty coin of 20 grams and 38 millimeters in diameter, the Spanish dollar is posited as the first global currency, having achieved a wide reach across the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans since the sixteenth century. As suggested in the 1708 list of foreign coins used in Virginia (see fig. 9), the Spanish dollar was a common currency in colonial North America, to the extent that it constituted half of the coins in circulation before Independence.24

Some of the “Christian” silver coins could also have been Dutch lion dollars.25 The leeuwendaalder was minted for circulation in VOC Indian Ocean networks in the seventeenth century (fig. 11). However, the leeuwendaalder had a lower silver content than the Spanish dollar and never managed to supersede its global dominance. Former American Numismatic Society curator John Kleeberg indicates that the leeuwendaalder could be found in New York, particularly between 1693 and 1733, and ties its presence directly to the short-lived but vigorous investment of New York merchants in the Madagascar trade, a topic discussed in more detail below.26

Unlike the Arabian chequins, the silver coins in Margrieta’s inventory are never mentioned by denomination. As such, their identity and objecthood are posited in a very different way than the foreign coins that sustained a consistent identity based on their face value—such as the ducat, which was understood as a distinct coin type regardless of the script that appeared on its surface. By contrast, the silver coins listed in this inventory are defined by three different characteristics: their origin, as defined in the broadest of terms (either “Christian” or “Arabian”), their quantity, and their weight. However, the individual weight of any one of these coins is impossible to isolate, because the weights were recorded in aggregation with other coins in addition to other items crafted of silver, which were likely both bigger and heavier. For instance, the eleven silver coins meant for Johanna were weighed along with two boxes, an egg dish, eighteen children’s toys, and a thimble, all made of silver totaling 51.5 ounces in troy weight, the standard used for precious metals.

While the gold coins (or ducats) and silver “Christian” coins mentioned in the inventory may be plausibly identified, the silver coins described as “Arabian” in this mixed group are more difficult to determine. Indeed, in 2009, the curators of the Bard exhibition could only speculate about reasonable candidates to represent them. As one possibility, they featured a silver mazuna, minted in present-day Morocco, noting that its weight equaled that of another coin fragment excavated from a colonial-era shipwreck.27 The other Islamic silver coin selected for the exhibition was a rupee minted under the name of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, dated 1691. This choice seems to have been based on the kinds of coins that Margrieta and her two husbands may have come across while posted in Asia, perhaps with the assumption that these items remained in the family’s possession from those stints abroad. Her first husband, Egbert van Duins (d. 1677), had previously been posted to the Mughal port of Surat before moving to Malacca, where he met and married Margrieta (see map/ map).28

Since the Bard exhibition, a series of new and surprising archaeological finds have emerged to shift our identification of the “Arabian” silver coins in the inventory. Namely, a significant number of silver coins from Yemen have been unearthed across colonial-era sites stretching from Connecticut to Maine. In 2018, archaeologists affiliated with the Connecticut Office of State Archaeology found a Yemeni silver coin at the Lt. John Hollister site in South Glastonbury, excavated at the edge of a building dating to the late seventeenth century (see map).29 This small coin, only 12.5 millimeters in diameter, is worn, and its edge has been chipped off, resulting in a ragged outline (fig. 12). As with the Arabian chequins, the coin is defined by an epigraphic program. The Arabic inscriptions on both sides are surrounded by a solid border within a dotted band. The inscription on its obverse, unevenly stamped, bears the honorific title “al-Nasir li-din al-haqq,” which refers to Imam Muhammad bin Ahmad of Yemen, who died in 1718. On the reverse, the partial inscription conveys a pious phrase, “the faith rejuvenated,” and includes the date, which can be discerned as 1692–93 (1104 AH).30

The Connecticut find joins several similar discoveries, such as a larger and much more pristine Yemeni coin specimen unearthed in Middletown, Rhode Island. A metal detectorist and historian named James Bailey found the coin in 2014 (see map). This coin bears a different regnal title, “al-Hadi,” and a very clear date, 1693–94 (1105 AH), along with the name of the mint site.31 Similar to the specimen featured in figure 13, this coin was produced in the Yemeni town called al-Khadra’, which was one of the ruling seats of Imam Muhammad bin Ahmad, who used three different titles during his rule, including both al-Nasir and al-Hadi (see map).32

These two Yemeni coins, both found in sites associated with colonial-era occupation, are not isolated specimens. Professional archaeologists and the metal detecting community have announced several other similar Yemeni coin finds from four states across the Northeast, including Massachusetts and Maine.33 Although some are too damaged or fragmented to be legible, at least eight can be identified with a certain level of precision.34 It is striking that they constitute a consistent corpus that can be related to comparative examples in international coin collections, such as the American Numismatic Society. All date to the same short time period, between 1689 and 1695. They were all minted by the same Imam, Muhammad bin Ahmad, during his long reign of over thirty years. I am confident that more Yemeni coins of this type will continue to turn up, particularly as commercial metal detecting equipment improves in its sensitivity and depth detection.

However, Yemeni coinage from this era is notoriously difficult to study. The weights and sizes of coins are incredibly varied, even within a single denomination, and the local textual sources do not correlate with material specimens in a clear or consistent way. Even so, the bulk of the identifiable coins from Yemen that have been found within this North American corpus appear to be of the same type.35 This coin type has been referred to using the Arabic vernacular term, khamsiyya (plural khamasi), which means five. The khamsiyya was a low-value silver coin, generally 12 to 16 millimeters in diameter and weighing an average of .72 grams.36 Most of the examples are razor thin and smaller than a dime.

The khamsiyya is well documented in the trade records of the European merchants who operated out of the Red Sea port of Mocha, in modern-day Yemen. Calling it the “commassee,” they singled it out as a local currency that circulated in that city’s market, tendered for everyday goods such as groceries and dry goods. As an example, on January 15, 1721, some supplies were purchased for the English trading factory at Mocha. Among other items, the list included some greens for four khamasi, milk for four khamasi, salt for two khamasi, eggs for nine khamasi, and fish for three khamasi. At that time, the exchange rate was forty-five khamasi to one Spanish dollar.37 Even while the khamsiyya was a local denomination, it was minted from silver mined at Potosí during a time when Spanish dollars were flooding the Arabian Peninsula for the coffee trade. In fact, the main Yemeni coffee market at Bayt al-Faqih only accepted cash in Spanish dollars, while other regional markets operated on credit.

Islamic coins have only very rarely been excavated at colonial American sites and usually stand as isolated finds without ready comparisons or detailed documentation.38 By contrast, the Yemeni coin finds described here come together to constitute a significant and consistent corpus of silver Islamic coins produced during a fixed time frame and deposited at various colonial sites across the Northeast. Given the locations where they have been found, their consequential number, and their narrow but highly compatible date range, I contend that at least some of Margrieta’s pieces of “Arabian silver money” were Yemeni khamsiyya coins.

I also want to underscore that the various labels that appear in the inventory—ducats, Arabian ducats, and Arabian and Christian silver money—were assigned by the assessors, not by Margrieta. In fact, Margrieta seems to have regarded these foreign coins, including the Yemeni khamsiyya, as more than mere liquid tender. On October 29, 1695, several weeks before she died, Margrieta wrote (or more likely dictated) her will, in which she determined which items to set aside for family members, leaving the rest to be sold off for her children’s benefit.39 Narrated in the first person, this document reveals her voice at a very fragile moment, when she was ill at the end of her life. As such, it communicates in a way that the inventory, compiled by the assessors after her death, does not. For this reason, the two documents, will and inventory, must be read together. Although the will conveys her final wishes, the inventory has tended to receive more attention from scholars.40

In her will, Margrieta earmarked for each child a bundle of goods, each wrapped in a napkin. While the will does not mention the “Arabian” silver coins specifically, the inventory does, along with other small, precious goods, under the subheading “For Johanna van Varick—Bound up in a Napkin.”41 She prepared a similar wrapped bundle for each of her children and notably doled out the four gold ducats equally among them. The two specified as “Arabian” were given to her daughters. The silver coins were also divided such that each child received between three and twenty, although only Johanna’s were described as “Arabian and Christian.” In contrast to the methodical reporting of the assessors, it is clear that Margrieta took personal care in dividing up and preparing these parcels as parting bestowals to her children.

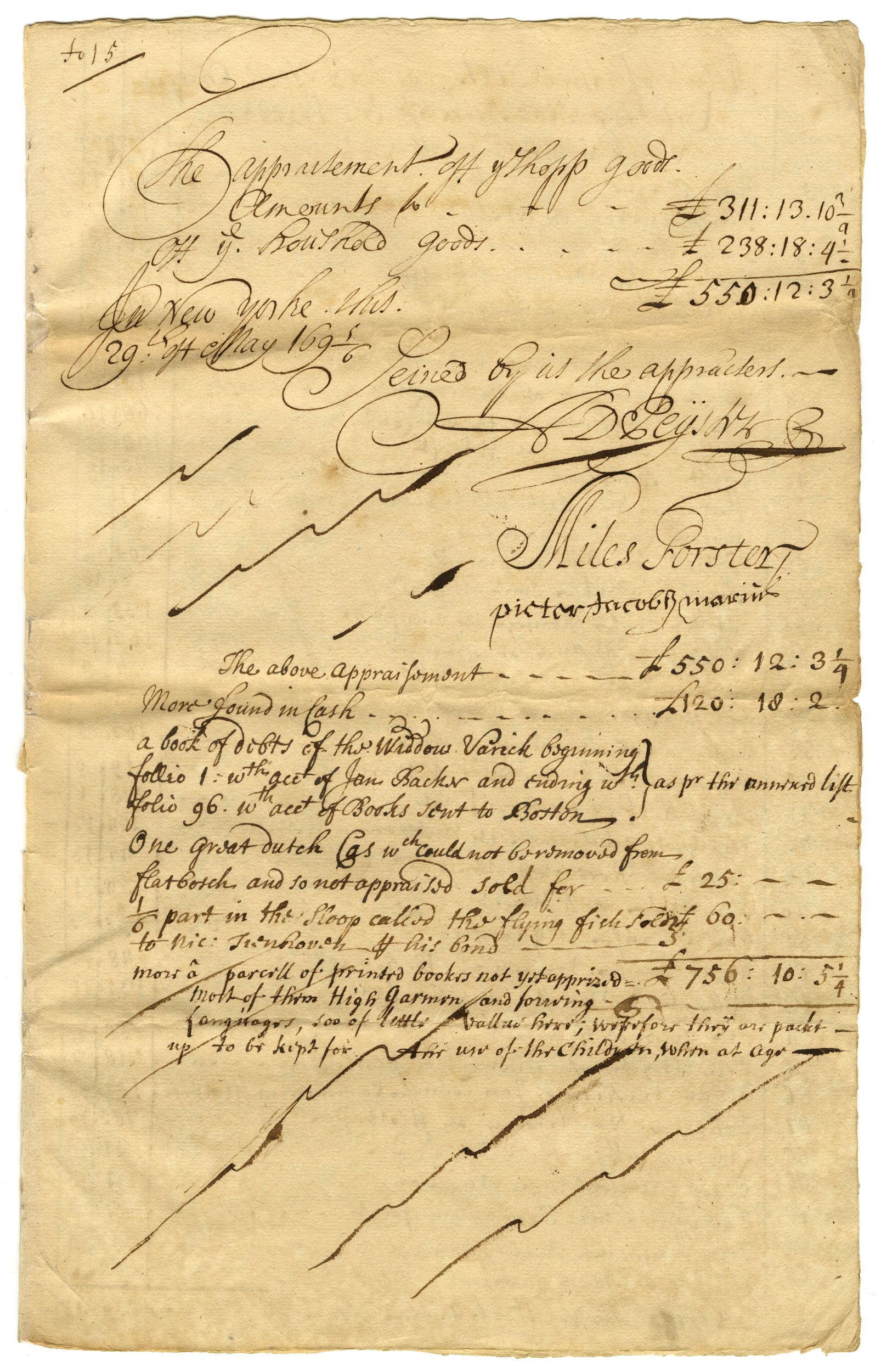

Indeed, these coins were treated differently from other forms of scattered cash held in the estate. The cash was tabulated by the assessors after Margrieta’s death and gathered up among the goods intended for auction. Rather than being singled out in the inventory as a particular type of coin or currency, this money was enumerated at the end of the assessed roster in a lump sum, appearing in one of its final lines as: “More found in Cash, £120:18:2” (fig. 14).42 This designation sets that money apart, cast in New York pounds, from the varied foreign coins described above, which were called out by denomination, identified as “pieces” expressed by their weight, and specifically wrapped and set aside for Margrieta’s children. This starkly differential treatment underlines how the array of foreign coins in her possession—whether Arabian chequins, Spanish dollars, Dutch leeuwendaalders, or Yemeni khamsiyya—constituted part of her personal and material object world. They were not treated as controvertible forms of cash or presented as direct sources of liquidity.

From Mocha to New York

As described above, some of the foreign coins held by Margrieta, namely the Arabian chequin, the Spanish dollar, and to a lesser extent the Dutch lion dollar, circulated quite fluidly as international currencies and could have arrived in New York through various channels of trade and exchange, via the Indian Ocean or the Mediterranean. Indeed, these coin types were transregional in their scope and played important roles in maritime trade circuits. By contrast, the Yemeni khamsiyya was a low-value currency with a very narrow purview of circulation. Even within Yemen, its usage zone was delimited to a small strip on the southern Red Sea coast in and around the port city of Mocha (see map).43 Because of its small range of standard circulation in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the khamsiyya thus offers a specific and very short-lived history of conveyance that can sharpen our understanding of the maritime relationships sustained between colonial New York and the Indian Ocean at the time of Margrieta’s death.

Although Yemen played a nearly exclusive role in the global trade of the coffee bean during this time, direct connections between Yemen and North America were not established until after American independence. Rather, during the 1680s and the 1690s, the maritime spheres of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans became closely linked through the activities of a group referred to as the “Red Sea pirates.” These Anglo-American pirates had long operated in the Caribbean but, finding their activities constrained, sought out new lucrative arenas. Historian Mark Hanna describes them as the “hundreds, if not thousands, of Englishmen who preyed upon Muslim pilgrims sailing in the Indian Ocean bound for Jeddah [Jidda], the largest port in the Red Sea and the gateway to Mecca . . . who based themselves mainly on the East African island of Madagascar.”44 They timed their arrival at Bab al-Mandab, the southern opening of the Red Sea, in order to seize pilgrimage ships traveling from Jidda on the return journey to the port of Surat in Gujarat (see map). Charged with carrying pious passengers, these vessels were also rich with precious metals, including the coin types mentioned above, and tended not to be heavily armed. The pirates targeted these ships with a sense of impunity, under the premise that it was justifiable to pilfer cargo carried by Muslims.45

Many famous Anglo-American pirates plied this route, such as Thomas Tew, Henry Every, and William Kidd. Every (also known as Avery) plundered a particularly well-outfitted Mughal pilgrimage vessel, referred to popularly as the Gunsway, owned by Emperor Aurangzeb, in the year 1695.46 Indeed, 1695 is a landmark year that marked more than Margrieta’s death. Every’s attack was singled out for the extreme brutality of the crew’s actions on board, in addition to the magnitude of riches that he and his crew seized. The infuriated Mughals retaliated against English establishments in India, which, in turn, led to a severe English crackdown against pirates in both the Atlantic and the Indian Oceans, a decisive change in the official response to such activities. Every himself was never caught, although some of his crew members were tried and hanged in London. Others escaped punishment and were even spotted in the colonies. After the infamous attack on the Gunsway in 1695, piracy suppression became a top priority in English maritime affairs.47

It is notable that pilgrimage ships like the Gunsway always stopped at the port of Mocha before exiting the Red Sea (see map). Mocha was the last major port of call before these vessels headed into the open waters of the Arabian Sea. The crew and passengers disembarked there to pick up fresh water and provisions before they began the most grueling seaborne leg of their return journey.48 Inevitably, they left the Red Sea with some khamsiyya coins in their possession as change from their transactions in Mocha’s market.

These pirates sustained a base on Saint Mary’s Island (Île Sainte Marie), today’s Nosy Baraha, off Madagascar (see map).49 After their exploits off the coast of the Arabian Peninsula, they would retreat to that island to repair ships and tend to the ill and injured, heavy with the gains they had seized from pilgrimage vessels. At the same time, this island drew North American merchants, particularly from New York. Colonial merchants had purchased enslaved individuals from Madagascar since the 1670s, but these efforts intensified in the 1690s and were deeply intertwined with pirate activity.50 These merchants provisioned the pirates on Saint Mary’s Island with supplies brought from the Atlantic world. They then, in turn, enslaved Malagasy people, who had been brutally captured, transporting them for sale back in the colonies. The traders saw Madagascar as an ideal target for a new and lucrative wing of the slave trade that sat outside the purview of the Royal African Company, which was founded in 1672 under an English charter and controlled the whole Atlantic coast of Africa. As historian Arne Bialuchewski describes in stark economic terms: “This legal loophole gave venturesome entrepreneurs an opportunity to set up a profitable trade, as slaves in Madagascar were much cheaper than those in West Africa.”51

This journey also provided a means for North American merchants to gain direct access to Indian Ocean goods, picked up at the Cape of Good Hope or acquired in the islands around Madagascar. In this way, they circumvented the circuits of trade that were tightly controlled and heavily taxed from sites such as Amsterdam and London.52 On the return journey to New York, many of these ships covertly ferried pirates to the colonies, where they sought haven and relative anonymity, provisioned with their newly acquired coins and loot.53 Indeed, some colonial governors overlooked or even welcomed these cash-rich arrivals, despite their checkered pasts.54 The governor of New York, Benjamin Fletcher, who held office from 1692 to 1697 and thus personally presided over the adjudication of Margrieta’s estate, publicly spearheaded legislation to suppress piracy, even as he made clandestine side deals to protect pirates from recrimination and to personally benefit from their activities. As Ritchie observes, “Under Fletcher’s administration the piracy business flourished.”55

However, this period of free passage and relative immunity, which brought together the voracious interests of Indian Ocean pirates, New York enslavers, and colonial merchants, was short-lived, reaching a height precisely in the mid-1690s, right around the time of Margrieta’s death.56 Every’s exploits in 1695 ended the tacit English tolerance for piracy and support of privateering. In 1698, Parliament authorized a new East India Company with monopoly rights, intended to end any direct trade between colonial America and the Indian Ocean.57

These new conditions affected even those voyages that were already in progress. As an example, the Margaret, owned by the New York merchant Frederick Philipse, a key investor in the Madagascar slave trade, set sail for the Indian Ocean in 1698.58 That vessel carried large quantities of wine, beer, and rum in addition to gunpowder and some “sundry” items. When the ship embarked on the return journey in 1699, with 114 or 115 enslaved people on board, it was stopped at the Cape of Good Hope.59 The cargo was seized, the slaves were sold at the Cape, and Captain Samuel Burgess was sent to London for trial, accused of collaborating with pirates and engaging in piracy himself. The seized goods included nutmeg, cloves, saffron, dyes, coins, broadcloth, porcelain vessels, Indian textiles, and more. The coins were broken down specifically as 9,800 pieces of eight, 2,000 gold chequins, and 7,500 lion dollars.60

Although they are not named among the coins brought back on the Margaret, some Yemeni khamsiyya coins were likely carried on that ship as it left Madagascar. In 1702, the Speaker sunk off the coast of Mauritius, with John Bowen, an infamous pirate, as its captain. Sources indicate that the ship had just come from plundering three vessels off the Arabian coast and was heading for Madagascar before veering off course only to sink just off that nearby island (see map).61 When a French team excavated the shipwreck in 1980, they found an array of coins, including six silver Spanish dollars minted in New Spain in denominations of four and eight, four Ottoman gold sultanis (or Arabian chequins), two Venetian ducats minted in the late seventeenth century, a Dutch lion dollar, three Yemeni khamsiyya coins, and a few other types.62 That set of finds, submerged for almost three hundred years, demonstrates the purview of pirate loot that is often referred to in generic terms as “coins of all nations.” Moreover, it illustrates how these coin types, the same denominations that Margrieta held at the time of her death, were aggregated when they were seized off the Arabian coast and then brought to the southern islands of the Indian Ocean.

In some ways, the khamsiyya can be compared inversely to the Arabian chequin. The golden Arabian chequin appears in text but has left no material trace from the colonial era. By contrast, the silver khamsiyya has been excavated or found in several colonial archaeological contexts but cannot be identified definitively in textual sources, even while plausible identifications, such as the present one, can be made. Additionally, the Arabian chequin was a high-value golden coin produced precisely for transregional exchange, while the khamsiyya was low in value and minted for local use within Yemen. Yet one can see the utility of the khamsiyya in the cash-poor colonies, where one of the biggest needs was for small change. This demand led to the frequent clipping of silver fragments from higher-value coins, such as the Spanish dollar, for practical use.63 Yemeni khamsiyya coins could thus fulfill a demonstrated demand for low-denomination tender, which may be why they remained in circulation and continue to be turned up by contemporary archaeologists and metal detectorists across New England.

Margrieta and the Indian Ocean

One might assume that this intertwined sphere of Indo-Atlantic trade, piracy, and enslavement had little to do with the world of Margrieta van Varick, a minister’s wife, mother of four, and a modest shop owner. Indeed, these coins from afar could have come into her possession through various means, possibly transferred to her by way of a patron in her shop. Yet this detached view of her life is untenable. Margrieta was connected to the Madagascar trade through her business ties and social circle; in fact, she may have been directly involved herself.64

In her will, Margrieta designated three people as executors: Nicholas Bayard, Charles Lodowick, and Jan Harperdingh.65 In the 2009 Bard catalogue, these choices were described largely based on her personal ties, emphasizing longstanding friendships and family connections. On his deathbed in 1694, her husband Rudolphus had called on Nicholas to attest to his will, thereby indicating his status as a reliable member of his circle.66 Surely, those ties were relevant to Margrieta, who, facing her own imminent death, would have been concerned with the welfare of her young children. At that dire time, she would have sought the most trustworthy representatives to ensure their well-being in her absence.

However, Nicholas and Charles may have also been her business contacts. Nicholas (1644–1707/11) has been described as the eleventh wealthiest man in New York during his era.67 Historian Cathy Matson also indicates that he was “widely known to have benefited from piracy in the 1680s,” when he served as a city councilor and then as mayor of New York, a position that rotated annually.68 Additionally, in the 1690s, Nicholas worked closely with Governor Fletcher, serving as his go-between with the various pirates and privateers who operated between New York and Madagascar.69 Nicholas was so invested in the Madagascar trade that he went to England to rally his allies against rising trade restrictions after the governor, his patron, had been recalled.70 His close associate Charles Lodowick (1658–1724) was an English merchant engaged in the fur trade, who held the positions of customs collector and then mayor of New York from 1694 to 1695. In 1692, Governor Fletcher dispatched both Nicholas and Charles to Albany, to aid the mayor of that city, Pieter Schuyler, during King William’s War.71 According to historian Kevin McDonald, Charles was also involved in the Indo-Atlantic trade.72 The third executor, Jan Harperdingh, does not appear to have been involved with these commercial activities, although he had served as an executor for several other estates among New York’s Dutch community, and so his experience would have positioned him well for this role.

These personal connections to merchants who were directly involved in the Madagascar trade provided Margrieta with access to some of the Indian Ocean goods that she sold in her shop.73 Moreover, Margrieta was financially invested in the shipping industry. After her estate was assessed, it was discovered that she held one-sixth ownership in a sloop called The Flying Fish, which was valued at 60 pounds.74 Yet, neither the inventory nor the will connect her shipping activities, or those of her associates, with the shop directly. Indeed, we know very little about Margrieta’s business. It is assumed that she started it as a way to care for her family after 1690, when her husband was caught up in the political drama brought on by the Leisler Rebellion, when English control of New York was overthrown in the wake of King James’ deposition. Implicated in the ensuing political drama in Flatbush, Rudolphus ended up in jail for a short time.75 This is a murky time in Margrieta’s life, when she briefly fled Flatbush, although it is unknown where she went or exactly when she returned.

Despite these uncertainties about Margrieta’s business dealings, the goods that remained unsold in her shop were recorded with great detail, across four pages and separated from those items that she left to her children and her general household effects. The majority of her shop merchandise was comprised of textiles, calculated by the yard or the ell (a historic unit of length, the Dutch ell was around 27 inches), along with some tailored items. The types of named textiles are diverse, including flannel, jersey, druggett, damask, calamanco, serge, calico, “Bengall,” linen, fustian, and more. She also sold sewing supplies such as thread, lace, buttons, thimbles, and pins, in addition to spices such as nutmeg, cloves, mace, cinnamon, and pepper. The spices and some of the textiles—namely the calico and the “Bengall” cloth, which was a type of muslin— surely came from the Indian Ocean trade.

Although the inventory does not elucidate how or when Margrieta acquired these items for resale, it is likely that she procured them directly through Indian Ocean channels, drawing on her connections to Nicholas and Charles, who were actively engaged in the Madagascar trade around the time of her death, or even via the boat in which she held shares.76 The maritime traffic between New York and Madagascar was regular, as indicated by Frank, who provides a list of eighteen such journeys conducted from 1690 to 1699, in addition to several others that landed at or were dispatched from nearby ports, such as Newport, Philadelphia, and Boston. Frank also notes that additional missions likely went unrecorded.77

This proposal diverges from that of the Bard curators, who tacitly suggested that Margrieta procured these eastern goods during her time in the Dutch Republic before arriving in New York, or even when she was in Malacca almost two decades earlier. Frank concurs with their earlier perspective, presenting the view that Margrieta and both of her husbands’ stays in Malacca allowed for the “accumulation of . . . alluring Far Eastern goods.”78 However, it is unlikely that Margrieta or her second husband, Rudolphus, would have had the foresight to acquire such copious quantities of Indian cloth or spices for resale before leaving Malacca. For instance, among the assessed items in the store, there were five pounds of pepper, nine and a quarter yards of “Bengall” textile, and at least nine different types of calico, equaling over thirty yards in total.

It is also possible that Margrieta provisioned some of the outgoing cargoes on these Madagascar missions. The shipments to that island included supplies that were intended for sale to the pirates who had just come from battles at sea and long maritime journeys. Ritchie underlines the particular need for clothes and tools used to make clothing, as pirates’ garments were subject to a great deal of wear and tear on the water.79 In this regard, we should return to the outgoing cargo of the above-mentioned Margaret that headed for Madagascar in 1698, which included six chests and seven casks of “Sundry merchandise.” Among these varied items were guns of various types, knives, flints, cloth, looking glasses, thimbles, scissors, ivory combs, buttons, tobacco pipes and boxes, and hats. Bulk items included sugar, lead, and tar.80 Margrieta’s store was replete with many of the named supplies. For instance, at the time of her death, the inventory of her shop merchandise included almost one hundred knives, thimbles, almost seventy pairs of scissors, twenty ivory combs and ten of horn, and tobacco boxes made of steel and wood, along with the textiles mentioned above.81 The list of shop goods also included fifteen mirrors, of which ten were described as “Indian looking glasses.”82

Additionally, specific items on these outgoing vessels were intended for the “local trade” in Madagascar, which obliquely indicates a category of goods used to barter for enslaved people, as well as local products such as ivory. As Bialuchewski describes, North American merchants profited from intertribal conflicts, in which local Malagasy groups, often from the coast, aided in enslaving people from rival communities on the island. He also indicates that “the indigenous people were keen to acquire beads, novelties, and copper or brass wire. Silver coins—the widely used Spanish pieces-of-eight—were also highly valued,” and guns increased in demand during this time.83 In 1698, the Margaret carried beads, brass neck collars, and armrings to Madagascar, presumably for this purpose.84 Similarly, Margrieta’s shop inventory included “49 glasse Necklaces” and “a remnant Copres.”85 It is notable that her shop carried significant quantities of some of the key items that would have been desirable to both the pirates who made temporary homes in Madagascar and the island’s resident human traffickers.

Lastly, it is surely possible that Margrieta procured some of the Asian goods among her personal belongings through the Madagascar trade, rather than acquiring them in Malacca or in Holland, as the Bard catalogue suggested. For context, we refer once again to the Margaret. In 1698, when the ship was about to be dispatched to Madagascar, the shipowner’s son Adolph Philipse made a request for a few specific items: “If you meet with a verry good Cabinet, bring that among the rest; Costs what it wil.”86 The following day, he added, “And if out of the Produce you can bring So much good China Ware (of the best) as will fit a Mantel peice, I desire you so to do. . . . The Cabinet that I ordered, let it be of the best you can gett.” Although it is not specified if these items were for his personal use or not, he was clear about their desired high quality and had a vivid idea of where the porcelain pieces would sit within a household, perhaps his own. The pointed nature of these requests suggests that these were not generic items intended for resale to a prospective unidentified buyer. In the end, the cargo of the Margaret never made it to New York, and Adolphe Philipse went all the way to London to recoup his losses. Even so, his sprawling Hudson Valley estate was filled with sumptuous items imported from Asia, made of porcelain and lacquer, as indicated by a mid-eighteenth-century inventory.87 Moreover, his repeated requests to the ship’s captain confirm that such items—namely movable hardwood furnishings (see fig. 2) and Chinese porcelain vessels, both which appear prominently on Margrieta’s inventory—were solicited through this channel. By extension, in the 1690s, the networks of procurement for and consumption of such desirable foreign goods in colonial New York were tied up with the brutal trafficking of enslaved people.

Bette of Flatbush

Margrieta was an enslaver, a fact that does not appear in her inventory. As historian Nicole Maskiell and others have amply demonstrated, she was not unique in this regard, as slavery underpinned the world of Anglo-Dutch New York City and its environs at this time. After listing the long roster of items that she wished to bequeath to her children in her will, Margrieta assigned the fate of “my neger girl Bette,” whom she invoked dismissively, using a pejorative Dutch term.88 Clearly an enslaved Black woman, Bette was cast in a callous and dehumanized manner, mentioned only in relation to the task with which she was charged: to care for Margrieta’s youngest child, Cornelia, until Cornelia reached the age of fourteen. In line with conventions of the time, Bette is presented as moveable property, likened indifferently to the “china butter dishes” and Margrieta’s “best black night gown,” all of which appear in the same section.

After Margrieta’s death, Bette likely remained in the role assigned to her, caring for Cornelia until she turned fourteen, which was around the year 1706 or 1707.89 Even if Bette remained with Cornelia beyond that age, her service would have surely reached its end after August 18, 1711, when, at the age of eighteen or nineteen, Cornelia married her first husband, Barent De Kleyn.90 Although it is not specified in the will or inventory, it appears that young Cornelia joined the household of Margrieta’s niece Maritje van Tienhoven and her husband, Nicolas, at some point following Margrieta’s death.91 Bette probably accompanied Cornelia to their residence, also in Flatbush, where she would have spent the next twelve or more years of her life. As Piwonka notes, in other inventories that mention enslaved individuals, provisions for their future, including if or when they should be emancipated, are often included. Neither Margrieta’s will nor her inventory include any such language regarding Bette. After that point in time, Bette’s trail goes cold; the documents related to Margrieta do not provide any further details.

Based on the context sketched in this essay, it is possible that Bette was brought forcibly from Madagascar and transported along the maritime route that linked the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic, at some point in the 1680s or 1690s. The anthropologist Wendy Wilson Fall has shown that the enslaved community in early colonial America was diverse beyond presumed West African origins. Ancestral roots to Madagascar are generally not evidenced by textual documentation; many descendant communities sustain their lineage to the southern Indian Ocean based instead on distant family memories or other modes of informal knowledge. Similarly, there are no solid figures about the number of enslaved individuals from Madagascar that arrived in New York at the end of the seventeenth century. Yet one can gain a sense of the scale of these movements through the shipping activity of Frederick Philipse. Records indicate that he spearheaded at least eight journeys between Madagascar and New York in the 1690s, involving 1,079 enslaved individuals, not all of whom survived the difficult maritime journey.92 Frank assesses that at least eighteen ships were dispatched on the route during this decade, including Philipse’s. By extension, an estimated total of 2,400 enslaved people can be proposed. That rough figure, as a very small fraction of the larger transatlantic slave trade, bolsters Wilson Fall’s assertion that “each ancestor from Madagascar serves a symbolic function as a claim to humanity that predates and survives the calamities of captivity, enslavement, and exile” and by doing so fuels the interest in learning more about this community.93

In 2005, the remains of two Malagasy women were found in a burial ground in Colonie, New York, north of Albany, New York. A historic map indicated that the area was previously part of the extended grounds of the Schuyler Flatts property, owned by Pieter Schuyler (1657–1724), mentioned above as the first appointed mayor of Albany and a member of one of the region’s most prominent colonial families.94 The Schuylers were described, along with the Bayards, van Cortlands, Stuyvesants, Philipses, van Rensselaers, and Livingstons, as being “bound together in an aristocracy of related wealth and position” in New York at this time.95 Maskiell also identifies the same families as enslavers, vividly demonstrating that slavery was central to sustaining their wealth and position at the turn of the eighteenth century.96 As underlined above, many of this group also profited directly from the Indian Ocean trade. For instance, Pieter Schuyler was noted as an investor in a 1698 voyage to East Africa.97 An inventory from the Schuyler Flatts estate, dated April 12, 1711, lists seven enslaved people, described as “negros and negrowomen” named Jacob, Charles, Peter, Thom, Anthony, Mary, and Bettie.98 Once again, this group of enslaved individuals was invoked simply as property, fully dehumanized and enumerated along with the horses, cows, sheep, and pigs on the farm.

The Schuyler Flatts burial plot was not used for members of the wealthy Schuyler family, who were buried elsewhere. Rather, the burials found in Colonie, dated to the 1700s or early 1800s, were modest in nature, and the bioarcheological data presented signs of physical stress consistent with lives of hard labor.99 Of the seven adults from whom viable MtDNA evidence was drawn, six were of African descent and one was likely of both Native American Micmac and African descent. The burial referred to as number 9 included the remains of a woman who was likely from Madagascar, as indicated by the MtDNA analysis, and died between the ages of fifty and sixty.100 Dental records show that her teeth were worn, consistent with smoking a pipe during her lifetime. She was around five feet four inches tall, with a “robust” build and “vertebrae fused from arthritis after years of hard work.”101 Burial 12 included remains of a younger woman, who died between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-five and was “probably born in New York but her DNA analysis indicates that her maternal ancestry was from Madagascar.”102 Standing at a height of around five feet two inches tall, this woman was, by contrast, “not quite muscular as the others but still had the early stages of arthritis in her back and joints,” which indicates that her tenure on the farm may have been shorter. All of the human remains from the excavation site, located along a busy commercial thoroughfare, were reburied respectfully in custom-designed burial containers at an official ceremony at the Saint Agnes Cemetery in Albany in 2016.103

It is tempting to suggest that the Bettie mentioned in 1711 at Schuyler Flatts was the same Bette who lived in Flatbush in 1695, or to surmise that the Bettie (or Mary) named at Schuyler Flatts in 1711 may be associated with the remains of one of the two Malagasy women unearthed near Albany. But we will probably never know what happened to Bette after Cornelia reached adulthood, or to Bettie and Mary after 1711. We also may never be able to confirm this proposal of Bette’s Malagasy origin. Rather, these stories are offered in parallel as a means to envision possible futures for Bette after she left Flatbush, even if they may have been bleak. Particularly, the Malagasy woman whom we can identify only through her remains, and the arbitrarily assigned burial plot number 12, presents a biographical profile that would be consistent with someone like Bette of Flatbush, whose life of enslavement could have shifted from domestic work and caregiving to the more demanding physicality of agricultural labor, until her life was cut short at a young age. These parallel stories also point to the far-reaching impact of the North American investment in the Madagascar slave trade, which extended far beyond New York City in the 1690s. Margrieta’s silver coins from Yemen compel us to ask more targeted questions and to seek evidence of Bette and the dispersed community of enslaved Malagasy people within these larger stories of bondage and oppression.

I have referred to the historic characters that are featured in this essay, such as Margrieta and Bette, by their first names. On one hand, this approach to naming helps to reduce confusion between Margrieta and her many family members with the same surname. Yet more pointedly, I follow the strategy presented by Maskiell, who intentionally levels the status of historical actors in her writing by referencing everyone on the terms by which enslaved people have been remembered, thereby consciously inverting the imbalanced conventions of the archival record.104 I have also followed Maskiell’s compelling model by pursuing a longer biography for Bette than Margrieta’s will or inventory provides, and by suggesting at least one possible trail out of Flatbush, while also recognizing the profound limits of our knowledge.105

Conclusion: A Trail of Coins

It is not easy to make claims about how any item reached its point of destination without a precise record of its historic itinerary. In this case, Margrieta’s inventory lists hundreds of goods; each would have traveled its own distinct journey to Flatbush and would have continued to move after leaving her estate. Many scholars before me have imagined Margrieta or one of her two husbands acquiring some of these goods in the Asian port cities of Surat or Malacca before transferring them to the Dutch Republic and eventually New York. Holland itself was a rich repository of goods from the east, where Chinese porcelain vessels in blue and white, ebony furniture, and calico cloth could have been procured before Margrieta’s family moved to Flatbush. Moreover, major trading centers such as Amsterdam and London re-exported items from the Asian trade to the other side of the Atlantic, another possible channel that could bring such goods into Margrieta’s hands while she lived in New York.

The Yemeni khamsiyya coins that appear on her inventory as “Arabian . . . silver money” offer a different yet very specific line of conveyance, from the port of Mocha in Yemen, out of Bab al-Mandab, and into the Arabian Sea. We can imagine one of these coins carried in the pouch of a pilgrim, who had newly acquired the title of hajji in Mecca, heading back home to India via the port of Surat. After leaving the Red Sea, the pilgrim’s ship, and thus the itinerary of the khamsiyya, would have been diverted from its intended route and seized by pirates, along with many other coins of much higher value. The coin’s journey would then have shifted toward the south, bringing it to Madagascar, possibly Saint Mary’s Island, where it would have been among the loot divided up by the crew. There it may have passed from a pirate’s hand to that of a merchant from New York, perhaps in exchange for a pair of scissors. This exchange would have sent our tiny silver coin on a path around the Cape of Good Hope into the Atlantic, likely on a boat that also would have carried enslaved people from Madagascar to the colonies, possibly to toil on a farm like Schuyler Flatts. The movements represented in this hypothetical telling were spurred on by acts of maritime violence, extreme brutality, and a disregard for human life, largely motivated by the desire for profit and personal gain.

In this essay, I have made the case for a new understanding of how some of the Indian Ocean goods in Margrieta van Varick’s estate may have ended up in her possession. While drawing on the important 2009 Bard exhibition that first spotlighted and elucidated Margrieta’s biography, I diverge from its focus on her travels to the east. Rather, I argue that some of the items on her inventory—namely those proposed to be silver coins from Yemen but also some of the bulk products that she sold in her store—arrived in New York via a maritime route plied by pirates and enslavers and were acquired by Margrieta after her arrival in the colony. By doing so, I assert Margrieta’s role as a shop owner, a businesswoman, and an enslaver, rather than focusing primarily on her identity as a niece, wife, widow, or mother.

I have also shed light on these maritime channels of procurement and transport as active processes, rather than ruminating on the static dimensions of ownership that an inventory, by nature of its genre, is meant to represent. Ultimately, this portrait depicts Margrieta’s New York not as a “Dutch” city, but rather as one node in an evolving Anglo-Dutch world that was deeply imbricated in contested Indian Ocean networks of piracy, plunder, illicit trade, and the brutality of enslavement in the 1690s, precisely at the time of her death. This moment marks a key maritime turning point when the rising interests of company and state expanded, thereby causing the English to seek greater maritime authority and overseas trade protection.

Coins of various types serve as the interpretational lynchpins of this study, powering the central argument in distinct ways and deflecting the assumption that such tokens operated as neutral media of exchange. In fact, Hoover stated how gold Arabian chequins became so associated with the illicit activities of pirates that they were eventually seen as tainted currency in the colonies.106 By extension, they also became associated with enslavement, to such an extent that the first published antislavery pamphlet in the colonies, The Selling of Joseph, written by Samuel Sewall in 1700, mentions in its opening lines “Arabian gold” as a recrimination to those who profited from the sale of human life.107 But I have also pursued Jennifer Morgan’s quest to decenter the seemingly empirical premises of economic history by providing alternative ways to think about the transactional relationships between money and enslaved African men, women, and children.108 To that end, Islamic coins of various types serve here as storytellers, occupying a central but improbable place in narrating occluded episodes from colonial American history.

This story of pirates, plunder, and enslavement also diverges from the standard account of Margrieta van Varick’s biography, which has been previously mapped on to the accepted vectors of Dutch expansion, highlighting the intimate domestic life of a colonial woman and her family. Indeed, the scattered silver and gold coins that appear in her inventory, covered with words in Arabic script, illegible to Margrieta herself, were material markers of her own imbrication in these increasingly contested circuits that stretched from Yemen to New York, threaded through the islands of the southern Indian Ocean. This essay has elucidated how some relatively small finds, dug out of the ground by archaeologists and hobbyists carrying metal detectors, can reorient our reading of Margrieta’s inventory. My hope is that it will bring into focus a short-lived moment in colonial North American history and encourage us to see the maritime spheres of the Indian and Atlantic Oceans as materially intertwined at the turn of the eighteenth century.

Cite this article: Nancy Um, “A Trail of Coins from Yemen to New York: Pirates, Plunder and Enslavement in the World of Margrieta van Varick, ca. 1695,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 11, no. 2 (Fall 2025), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.20342.

Notes

For someone who generally works in the Eastern Hemisphere, this essay represents an unusual foray into the world of colonial North America and its vast scholarship. I embarked on this unlikely journey in order to better understand the story behind a curious corpus of seventeenth-century Yemeni coins that began appearing at colonial sites in New England over a decade ago. I offer thanks to those who helped me along the way, including many audiences who heard versions of the talks that led to this essay at Johns Hopkins, Princeton, University of Pennsylvania, the European University Institute in Florence, UCLA, University of East Anglia, Yale, and the New Netherland Institute Scholars’ Seminar. I thank Deborah Krohn and Meredith Martin for their friendship and for commenting on drafts of this essay; the editors and anonymous reviewers for Panorama, who provided excellent suggestions for the improvement of this article; and Lidia Ferrara for her generous assistance with research, sources, editing, and development. Nevertheless, I must accept my relative dilettantism as a necessary condition of doing work that is unruly in its global scope and of studying interactions that refuse to be bound by the kinds of subfields that order our discipline today. I take responsibility for any errors of interpretation, and possibly also of fact, while also inviting those who hold expertise in this field to build on my preliminary proposals and to see this modest contribution as a mere spark for what I hope will be further studies.

- Esther Chadwick and Cécile Fromont, introduction to “A Vast Early Modern Atlantic,” special issue, Art History 46, no. 5 (2023): 859. ↵

- Esther Chadwick, “The Aesthetics of Postrevolutionary Haiti: Currency, Kingship, and Circum-Atlantic Numismatics,” in “A Vast Early Modern Atlantic,” 1014–45. ↵

- Chadwick, “Aesthetics,” 1016. ↵

- Laura Kalba, “Beautiful Money: Looking at La Semeuse in Fin-de-Siècle France,” Art Bulletin 102, no. 1 (2020): 56. ↵

- In this essay, I endeavor to follow the model of historian Nicole Maskiell by referring to historical figures by their first names, both adults and children, even when their surname is known. This is an intentional strategy that can unsettle “systems of oppression and silences.” Nicole Maskiell, Bound by Bondage: Slavery and the Creation of a Northern Gentry (Cornell University Press), 11-12. ↵

- David William Voorhees, “Flatbush in the Time of the van Varicks,” in Dutch New York Between East and West: The World of Margrieta van Varick, ed. Deborah L. Krohn and Peter N. Miller (Yale University Press in association with Bard Graduate Center and the New-York Historical Society, 2009), 84. Hereafter, I refer to the Bard catalogue as simply Dutch New York. ↵

- Susanna Shaw Romney, New Netherland Connections: Intimate Networks and Atlantic Ties in Seventeenth-Century America (University of North Carolina Press, 2014). ↵

- “Appendix: The Inventory of Margrieta van Varick,” in Dutch New York, 347, fol. 5. Throughout this essay, reference is made to the copy of Margrieta van Varick’s inventory filed in the Court of Appeals in 1719, held today in the New York State Archives, relying on the useful reproductions and transcriptions published in Dutch New York. Folios are cited with reference to the exhibition catalogue page number and the corresponding manuscript folio number. However, it should be noted that the 1719 copy includes an error in numbering; two consecutive pages are numbered as folio 14. ↵

- Caroline Frank, Objectifying China, Imaging America: Chinese Commodities in Early America (University of Chicago Press, 2011), 4. See also Jonathan Eacott, Selling Empire: India in the Making of Britain and America, 1600–1830 (University of North Carolina Press, 2016). ↵

- Ruth Piwonka, “Margrieta van Varick in the West: Inventory of a Life,” in Dutch New York, 108, 112–13. ↵

- Marybeth De Filippis, “Margrieta van Varick in the East: Traces of a Life,” in Dutch New York, 44. ↵

- Other scholars have accepted the tacit assumption that these goods were procured by Margrieta or her husbands while in Asia. See James Bailey, “Late 17th Century Arabian Coins Found in Southern New England: Uncovering the Evidence and History of Red Sea Piracy in Early America,” Colonial Newsletter: A Research Journal in Early American Numismatics 57, no. 2 (2017), 4612; Frank, Objectifying, 3. ↵

- Robert Ritchie, Captain Kidd and the War against the Pirates (Harvard University Press, 1986), 38. ↵

- The Bard catalogue provided an example minted in Utrecht in 1643. Dutch New York, 234, cat. no. 78. ↵

- “Massachusetts Bay Silver 1652–1682: General Introduction,” Coin and Currency Collections in the Department of Special Collections, University of Notre Dame Libraries, archived February 3, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250203074315/https://coins.nd.edu/colcoin/colcoinintros/MASilver.intro.html. ↵

- Philip Mossman, Money of the American Colonies and Confederation: A Numismatic, Economic, and Historic Correlation, Numismatic Studies 20 (American Numismatic Society, 1993), 29. ↵

- John McCusker, Money and Exchange in Europe and America, 1600–1775 (University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 157, 159; “Appendix: The Inventory of Margrieta van Varick,” in Dutch New York, 360, fol. 17. ↵

- Chadwick, “Aesthetics,” 1016. ↵

- Eric Helleiner, “One Nation, One Money: Territorial Currencies and the Nation-State,” 1997, University of Oslo, ARENA Centre for European Studies, working paper 97/17, https://www.sv.uio.no/arena/english/research/publications/arena-working-papers/1994-2000/1997/wp97_17.htm. ↵

- Oliver Hoover, “The Real Forgotten Coins of North America: Islamic Gold, Silver, and Copper from the Eastern Trade,” Colonial Newsletter: A Research Journal in Early American Numismatics 53, no. 3 (2013): 4071. ↵

- The term chequin was derived from the word “sequin,” based on the Italian term zecchino, which happened to be drawn originally from the Arabic term sikka, which means mint. ↵

- As one indication of the limited scope of circulation of these coins, a survey of hundreds of published abstracts of New York wills issued from 1665 to 1707 surfaces only four with any mention of the Arabian chequin or ducat, one of which was Margrieta’s. Abstracts of Wills on File in the Surrogate’s Office, City of New York, vol. 1, 1665–1707, New-York Historical Society Publication Fund 25 (New-York Historical Society, 1892), 97, 271, 272, 310, 449. ↵

- Hoover, “Real Forgotten Coins,” 4074. ↵

- “Spanish Silver: General Introduction,” in Coin and Currency Collections in the Department of Special Collections University of Notre Dame Libraries, archived February 3, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250203124827/https://coins.nd.edu/ColCoin/ColCoinIntros/Sp-Silver.intro.html. ↵

- In regard to the inventory, John Kleeberg asserted that the silver “Christian” coins could not have been leeuwendaalders. His contention was based on an assumed total value of the silver in the estate, which included the items set aside for her children, although these were not factored into the assessors’ final appraisals. John M. Kleeberg, “The Circulation of Leeuwendaalders (Lion Dollars) in England’s North American Colonies, 1693–1733,” Colonial Newsletter: A Research Journal in Early American Numismatics 53, no. 2 (2013): 4039. ↵

- Kleeberg also underlines that the leeuwendaalder’s presence in New York at that time should not be correlated with the city’s large Dutch population, then under English rule. Kleeberg, “Circulation,” 4032. ↵

- Entries by Robert Wilson Hoge, Dutch New York, 238, cat. nos. 80–87. To this point, in 2013, a metal detectorist in North Carolina found a late seventeenth- to early eighteenth-century holed coin of that type and posted about it on an online message board. Screwynewy, “Dug a hammered silver coin – but its {sic} not Spanish,” May 28, 2013, TreasureNet, https://www.treasurenet.com/threads/dug-a-hammered-silver-coin-but-its-not-spanish.356592. ↵

- De Filippis, “Margrieta van Varick in the East,” 46; Entries by Hoge, Dutch New York, 236, 238, cat. no. 85. ↵

- Brian D. Jones, “The 17th Century John Hollister Site in South Glastonbury, Connecticut,” Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Connecticut 81 (2019), n.p., fig. 15. Thanks to Sarah Sportman for providing information and the permission to publish this find. The Connecticut Office of State Archaeology offers excellent online documentation of the Hollister site: https://osa.uconn.edu/home/recent/hollister. ↵

- Nancy Um, “Linking Seventeenth-Century Yemen to Colonial New England: A Closer Look at Silver Coins Across the Indian and Atlantic Oceans,” American Journal of Numismatics 36 (2024): 369–70. The Yemeni coins in this essay and in the accompanying map are referred to by their Common Era (CE) date range, derived from the Islamic calendar date, marked by AH. ↵

- Bailey published this coin find in 2017, and his story was widely popularized across media outlets in 2021. Bailey, “Late 17th Century Arabian Coins”; William J. Kole, “Ancient Coins May Solve Mystery of Murderous 1600s Pirate,” Associated Press, April 1, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/ancient-coins-may-solve-mystery-1600s-pirate-f5a6151b74e0dcf96de585eab451f90c. ↵

- For more information about this imam, see Nancy Um, “From the Port of Mocha to the Eighteenth-Century Tomb of Imām al-Mahdī Muḥammad in al-Mawāhib: Locating Architectural Icons and Migratory Craftsmen,” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 41 (2011): 387–400; and Nancy Um, “Foreign Doctors at the Imam’s Court: Medical Diplomacy in Yemen’s Coffee Era,” Genre: Forms of Discourse and Culture 48, no. 2 (2015): 261–88. ↵

- These finds are documented unevenly, often on online message boards used by the metal detecting community. Bailey provided a lengthy, but not comprehensive, list based on direct communication with the various finders. Bailey, “Late 17th Century Arabian Coins,” 4581–86. In 2023, Bailey attested that thirty Middle Eastern silver coins have been found on the east coast of the United States, twenty-three of them in New England. James Bailey to the author, July 7, 2023. ↵

- These coins and fragments bear some pieces of legible information, usually a part of the title of the ruling imam, a date, or the mint site, and they can often be dated based on comparison with extant examples in global numismatic collections. The list of eight includes finds beyond those that Bailey documented (2017), while also omitting those exemplars that could not be verified by this author based on the reproductions. Um, “Linking,” 366–77. ↵

- Um, “Linking.” The weights, across different issues of the coin, range between .299 and 1.02 grams. This coin type was frequently redesigned with new formats and epigraphic formulas during this time period. ↵

- This average is based on twelve specimens held in the British Museum, the Ashmolean, and the American Numismatic Society and documented on the coin crowdsourcing site, Zeno.ru.—Oriental Coins Database, https://zeno.ru. For a full account, see Um, “Linking,” 368–76. ↵

- Stewards Account of Disbursements for the Month of January 1721, G.17.1, fols. 207–8, British Library, London. ↵

- Two historic examples include the now-lost Malden Hoard of square copper coins, proposed to be Mamluk and found in Malden, Massachusetts, in the late eighteenth century during the construction of the rail line; and a late seventeenth-century Mughal copper dam, minted in Surat under Emperor Aurangzeb, found at Fort Pentagoet in Castine, Maine. Hoover, “Real Forgotten Coins,” 4075; Alaric Faulkner and Gretchen Faulkner, The French at Pentagoet, 1635–1674: An Archaeological Portrait of the Acadian Frontier (Maine Historic Preservation Commission, 1987), 259–60. The other specimens have been found by the metal detecting community. Bailey published a holed Ottoman akçe from the late seventeenth century that was found by a metal detectorist named Tim Larkin in Norwell, Massachusetts, and another silver coin that may date to an earlier period from Yemen, found by Paul Davis in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Bailey, “Late 17th Century Arabian Coins,” 4582–85. ↵

- “Appendix: The Will of Margrieta van Varick,” in Dutch New York, 337–340. ↵

- “Appendix: Transcriptions of the Wills and Administration Papers of Rudolphus and Margrieta van Varick,” in Dutch New York, 333. ↵

- “Appendix: The Inventory of Margrieta van Varick,” in Dutch New York, 343, fol. 1. ↵

- “Appendix: The Inventory of Margrieta van Varick,” in Dutch New York, 358, fol. 15. ↵

- In 1768, the German traveler Carsten Niebuhr noted that the khamsiyya was not used in the port of al-Luhayya, located around 300 kilometers to Mocha’s north, where a different denomination called the bali dominated. Carsten Niebuhr, Beschreibung von Arabien (Copenhagen: Nicolaus Möller, 1772), 218. ↵

- Mark G. Hanna, Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570–1740 (University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 185. ↵

- Ritchie, Captain Kidd, 87. ↵

- Steven Johnson, Enemy of All Mankind: A True Story of Piracy, Power, and History’s First Global Manhunt (Random House, 2020). See also Bailey, “Late 17th Century Arabian Coins,” 4588–17. ↵

- It is noteworthy that none of the Yemeni coins found in North America have been dated beyond 1695. ↵

- As an example of such a journey, see “Anis al-Hujjaj,” an account left by a pilgrim from India named Safi bin Vali in 1676–77. His journey from Mecca included stops in Jidda and Mocha before finally docking in Surat. Nancy Um, “From Surat to Jidda: Picturing the Western Indian Ocean Port City,” in The Sea and the Mobility of Islamic Art, ed. Radha Dalal, Sean Roberts, and Jochen Sokoly (Yale University Press, 2021), 184–99. ↵

- Kevin P. McDonald, Pirates, Merchants, Settlers, and Slaves: Colonial America and the Indo-Atlantic World (University of California Press, 2015), 55; Ritchie, Captain Kidd, 112–26. ↵

- Hanna, Pirate Nests, 186. ↵