Art and Narrative: The 2022 AHAA Seventh Biennial Symposium

PDF: Caskey, Art and Narrative

This year’s 2022 AHAA Seventh Biennial Symposium was co-hosted by Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, and the University of Arkansas’s School of Art in Fayetteville. The symposium was preceded by a series of free lectures held in honor of the ten-year anniversary of the Tyson Scholars of American Art Program at Crystal Bridges and featured conversations between past Tyson Scholars and contemporary artists Patrick Martinez, Anna Tsouhlarakis, and Consuelo Jimenez Underwood. As a recent Tyson Think Tank Scholar, I was encouraged by the large community of scholars who returned to Bentonville to share their recent research and engage in conversations about queering art history, the colonial and imperial impact on landscape, and the turmoil of philanthropy in today’s museums.

The keynote speaker of the symposium was Chilean-born artist Alfredo Jaar, who delivered an engaging lecture that explored his thought process behind recent projects that share the stories of those experiencing homelessness, refugees, and victims of natural and human-made disasters. Jaar imparted on attendees that “art was given to us to change the order of our reality.” I interpreted this statement as a call to action that the artists and art historians who presented at and attended the symposium must uphold through their scholarship and curatorial work.

Over the next two days, art historians exchanged ideas in eight thought-provoking sessions and two workshops on a variety of themes, including materiality, decentering collections, rethinking historical borders, and the breadth of art and empire. In this wrap-up, I focus on a handful of presentations that I was able to attend.

Friday’s “Material Histories” session focused on how the materials used in creating art can reveal complex and sometimes violent histories. Colton Klein of Columbia University presented on Minnie Evans’s Airlie Oak (1954; Smithsonian American Art Museum)—an oil on wood relief painting that took over three years to carve. Klein explained that the use of turpentine in Airlie Oak was Evans’s way of commenting on the dark history the native resource had on the North Carolina area. Although the oak trees yielding turpentine were profitable, the labor was hazardous to the many enslaved Black people forced to harvest it. Moreover, while the forest of oaks could serve as a place of refuge for those fleeing enslavement, they were also sites of lynching, as described in Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem The Haunted Oak (1913). Additional presentations by Jennifer Chuong of Humboldt University and Ramey Mize of the Portland Museum of Art, Maine, also drew attention to the complicated histories of environmental exploitation and how as artists, scholars, and consumers we should take interest in how products are made.

Later that day, a session titled “Activating Collections: Case Studies in Decentering” explored the different ways museums and art historians can tell the entire history of objects, spaces, and peoples that have previously been whitewashed, ignored, or silenced. Presenters offered examples of reinstallation and copartnering with contemporary artists as ways museums can disrupt outdated and exclusive narratives. Janine Yorimoto Boldt of the Chazen Museum of Art spoke on the institution’s efforts to decenter its collection by sharing the entire narrative behind historically complex artworks. The lecture focused on Thomas Ball’s sculpture Emancipation Group (1876; Chazen Museum of Art), a depiction of a standing President Abraham Lincoln breaking the shackles of a kneeling black man, which Boldt noted has been criticized for showing “Black freedom as an act of white power.” The Chazen’s responsive collaborative exhibition, titled re:mancipation, unpacked the sculpture’s past as a way to educate the public of the sculpture’s history and encourage them to have a more critical eye.

Saturday morning kicked off with “Border Crossings,” a session that reinforced how expanding the field of American art requires greater attention to the often-undermined or invisible agency of non-European and Indigenous peoples. Erin Pauwels of Temple University presented on Shugio Hiromichi, a Japanese diplomat who was instrumental in spreading the popularity of Japanese art in the United States. Pauwels pointed out that the japonisme craze did not just happen in Western culture by European discovery, but that instead it was curated by individuals like Hiromichi, who advocated for the cultural richness of his native country. Bart Pushaw from the University of Copenhagen shared the artistry of the Inuit people (specifically the Indigenous people of Greenland) and how their rich artistic output was involved—through the networks of colonialism—in systems of cultural and material exchange that span the Western hemisphere. Pushaw argued, for instance, that a decorated tobacco pouch made by an Inuit woman not only reflected the international tobacco trade made possible by the plantation system of the American South but also paid homage to the blubber industry of Greenland. This session, like “Material Histories,” took a critical look at how the commodification of materials and their networks of exchange can inform the way we interpret objects as art historians.

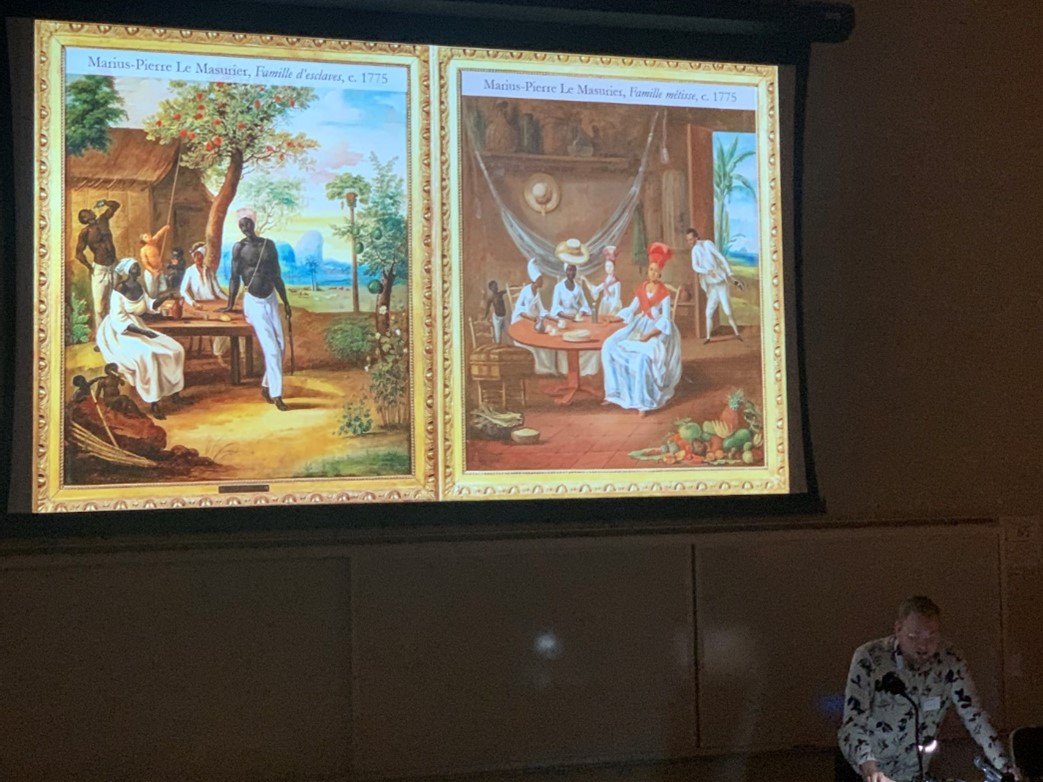

The final panels of the conference were open sessions, including one addressing “Art and Empire.” Kate Clarke Lemay of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, presented on an upcoming exhibition on US imperialism—specifically within the islands of the Caribbean and Pacific. Lemay’s talk introduced narratives of the people of Cuba, Hawai‘i, Puerto Rico, and others who were a part of the “Spanish-American War.” The National Portrait Gallery will not be using that name for the war and will instead designate it as the “War of 1898” to draw attention to all the nations who perpetuated and were affected by it. Similarly, Ashley Williams of Columbia University focused on the overlooked prison laborers of the Philippines who supplied the wicker furniture craze of the early twentieth century. As in the “Decentering” and “Border Crossing” sessions, these presenters showcased those whose names and contributions have been whitewashed and anonymized by mainstream narratives of history and statecraft, like prison industrial complexes.

The 2022 AHAA Seventh Biennial Symposium brought together a diverse yet complementary group of themes. Each session explored ideas of complex materiality, recontextualizing art and art collections, and (re)visions of imperialism. Overall, the symposium was an intellectual and (as time will tell) hopefully fruitful success for all attendees.

Cite this article: Lauren Caskey, “Art and Narrative: The 2022 AHAA Seventh Biennial Symposium,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15400.

About the Author(s): Lauren Caskey is a PhD Candidate at The Ohio State University and a 2022 Tyson Think Tank Short Term Fellow.