By Which Melancholy Occurrence: The Disaster Prints of Nathaniel Currier, 1835–1840

The hapless steamboat Lexington left New York for its usual run up to Stonington, Connecticut, at three o’clock in the afternoon on January 13, 1840, carrying passengers and a cargo of cotton bales. The day was particularly cold and the seas beyond Throgs Neck particularly high; almost all the passengers aboard elected to pay the extra 50¢ fare to be off the deck and inside the luxurious heated cabins. The passengers had just finished dinner when, at about seven o’clock, the first mate reported that a fire had broken out in the cotton stowed on deck. Flames quickly engulfed the ship. The captain attempted to steer the vessel to shore but lost control when the rudder ropes burned through. The two aft lifeboats were dispatched; one was shattered by the wheel, and the other was swamped in the chaos. Frantic passengers and crew threw cotton bales into the icy water to use as rafts, to little avail. Of the approximately 140 people on board, only 4 survived.

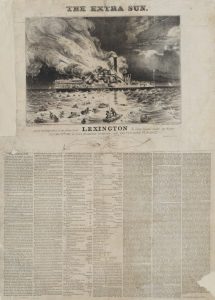

While the disaster sent a wave of trepidation across America, it augured a brilliant future for the fledgling printing firm of N. Currier—known after 1857 as Currier and Ives.1 Nathaniel Currier’s lithographic print Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound on Monday Eveg, Jany 13th 1840, by which Melancholy Occurrence, over 100 Persons Perished, 1840, appeared in record time and was delivered through the uncommon distribution mode of a news extra. It propelled him to national prominence. The success of this print portends some of the rhetorical tactics—and the sensitivity to audience response—that would eventually allow Currier and Ives to dominate the nation’s lithography market in the nineteenth century.2

Although Currier’s early prints of disasters are frequently noted for their foundational role in the history of the firm, the imagery itself has received little attention. The present study examines four of his early disaster images, from his first foray into this subject matter in 1835 to the Lexington disaster in 1840. It isolates a seminal moment in American visual culture to examine the aesthetic and rhetorical formulae employed by Currier and his collaborators in these prints and why they resonated with America’s growing middle class. Currier’s lithographic representations of catastrophes performed a unique function among the cultural productions of the day: they combined the potential of the lithographic medium with an innovative visual lexicon, one that managed a complex set of psychological and cultural tensions to appeal to the sensibilities of a broad swathe of antebellum viewers. Comprising some of the first lithographs on newsworthy subjects disseminated in the United States on a mass scale, these “marketable” disasters portrayed large-scale events and often featured a modern technology or system abruptly and dramatically undermined by primal natural forces. The prints gave an unprecedented visual immediacy to incidents that loomed large in the public imagination, at a price that made them widely accessible. The particular success of these prints rested on their invocation of extant pictorial tropes, such as architectural prints and ship portraits, in a way that attended to the expectations, hopes, and fears of a newly minted audience of consumers of visual culture. Simultaneously more spectacular, imaginative, and subtle than the newspaper reports of the same events, more immediate and local than “high-art” renderings, and more enduring than theatrical performances, these first Currier lithographs gave viewers a space in which to contemplate the vicissitudes of fortune, serving as a catalyst for critical reflection. They made the fault lines of early- to mid-nineteenth-century American life visible while concurrently reassuring and consoling their viewers, reflecting and helping to construct the appropriate responses of period audiences.

To understand representations of disaster in the 1830s and 1840s, we must first examine the semantics of the term within the historical context. A survey of antebellum news sources indicates that writers applied the word disaster liberally to a range of events—everything from a single death to a mass loss of life or property. Disasters usually entailed an unforeseen disruption of everyday life and could be caused by both natural and technological forces: fires, violent storms, floods, earthquakes, industrial mishaps, and ship- and train wrecks. But the word was also used more figuratively and appeared frequently in discussions of economic or political policy.3 The indiscriminate use of the term speaks to the meaning and social function of disasters in the era: the origin of the word disaster—from the Italian, meaning “ill-starred”—is retained in antebellum associations, consistently linked as it is in the Victorian mind with fate or Providence.4 Individual fates, the fate of the economy, the fate of one’s business, and the fate of the nation or of humanity were all abiding preoccupations in the pre–Civil War era. In this period, any sudden occurrence perceived to divert or truncate the course of individual, community, or state qualified as a disaster. Any unexpected incident—great or small—seemed to warrant a moment of reckoning with destiny and the many issues that might attend it.

Within this broad understanding of disaster, Currier productions isolated very specific moments: his early prints favored newsworthy, dramatic ruptures in the destinies of a large number of people. The events to which he applied his presses were visually seductive, awe-inspiring public spectacles. Such representations offered an opportunity to reflect on these events and what they might mean for the viewer’s own condition. While individual reactions to historical images were seldom documented, an analysis of the sociocultural factors that inflected the viewing of Currier’s prints can provide insight into the conditions under which the images could generate meaning.

Rising from the Ashes: The Great Fire of 1835

Nathaniel Currier (1813–88) lived in tumultuous times. His own life trajectory and those of many of his associates arced across one of the most economically, socially, and politically volatile periods in American history—one marked by financial downturns, military conflicts, and massive physical and class dislocations as the tottering republic found its balance and matured into a modern industrial society. Currier’s seventy-five years on this earth also witnessed the advent of technological marvels—steam-powered ships and railroads—that remodeled the topography of the country and radically altered the flow of people within it. Such transformations brought with them the possibility of catastrophic conflict and sudden, grisly death on a grand scale. Visible evidence of this instability frequently recurs in the more than seven thousand images of the firm of Currier and Ives over its seventy-year existence. Fires and shipwrecks punctuate the perhaps more familiar collection of pleasant “scenes from American life” that range from kittens to sporting scenes to bucolic domestic tableaux. Into this mix, the publishers also injected scenes of deadly conflict from the Civil War and western expansion, as well as blatantly political, editorial, or socially prescriptive images.5 Such contrasts and tensions occur across the images of Currier and Ives’s oeuvre and, at times, within individual prints.

In 1813, when the young republic was embroiled in its final, definitive battle for independence, Nathaniel Currier was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts. At the age of fifteen, Currier became an apprentice to one of the first lithography firms in America, Pendleton’s Lithography, in Boston, working with the brothers William S. (1795–1879) and John B. Pendleton (1798–1866). He was exposed to all aspects of the business in this small shop, from artistic creation to production.6 Here he trained for three years alongside fellow apprentice John Henry Bufford (1810–70). Bufford, who hailed from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, would become an important collaborator on Currier’s first successful works. Along with scores of others in the Jacksonian period, Currier and Bufford moved to New York City, and each set up a shop, in 1834 and 1835, respectively. Currier’s first two business ventures in the city—a proposed enterprise with John Pendleton and a partnership with a man by the name of Stodart—both collapsed by 1835, after which Currier established a sole proprietorship. Until the publication of the disaster images on which this study focuses, Currier was exclusively a job printer, producing only the materials that clients requested, such as letterhead.

At this time, lithography was a corporate enterprise, regularly involving collaborations within shops or even among erstwhile competitors. Nineteenth-century lithographic prints thus defy any straightforward notions of authorship, posing intriguing problems for modern observers with respect to intentionality. The individual contributions of draftsman, printer, publisher, and distributor are most often impossible to distinguish, and few of Currier’s business records survive. The documented practice of Currier’s later printing concern with James Ives—perhaps learned at the Pendleton shop—entailed a joint effort in which one or more associates might refine another artist’s work as it went from sketch to stone, based on suggestions by the publisher.7 Although possibly trained as a draftsman in his apprenticeship, Currier hired or commissioned other artists—including Bufford—to execute the imagery of the prints that bear his name, and while Bufford had his own lithography concern, he generally allowed others to come up with subject matter.8 In the early days, both men often chose to share with others—or abdicate altogether—the financial risks of publishing their lithographs and turned to someone like John Disturnell (1801–77), a writer, printer, and book dealer known for publishing guidebooks, to help distribute their output.9 In the case of the first widely distributed disaster print issued by “N. Currier’s Press,” for example, Bufford is credited as artist and Bufford and Disturnell as publishers.

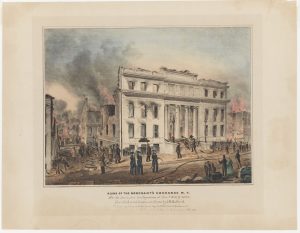

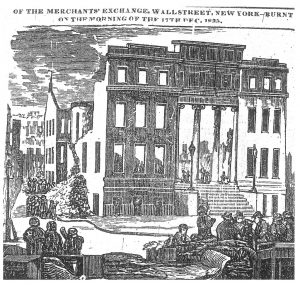

On December 16, 1835, the year that the twenty-two-year-old “N. Currier” opened an office at 1 Wall Street, a great fire broke out in New York’s business district, consuming more than thirteen acres of the city. The Currier-Bufford-Disturnell collaboration, Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange N.Y. after the Destructive Conflagration of Decbr. 16 & 17, 1835, 1835—a lithograph issued initially in black and white and later in a hand-colored version—appeared within days of the fire.10 While newspapers were capable of incorporating rough woodcut imagery in pace with the news cycle, their editors greatly favored text and only used small illustrations, if any. Hence, “the dazzling speed of Currier’s presses created a sensation.”11 This print—one of his first forays into original subject matter—reportedly sold in the thousands and helped to establish Currier’s local reputation.12

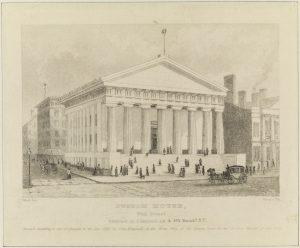

At the time of the Great Fire of 1835, New York City was a burgeoning metropolis into which people were pouring from both the countryside and overseas. In 1800 the city could claim a population of sixty thousand, but by 1830, this number had more than quadrupled, growing to nearly two hundred fifty thousand. The influx of people resulted in social instability and overtaxed municipal systems at the most basic levels. Exponential population growth quickly outpaced services, and sanitation and firefighting were inadequate, to say the least.13 With increased density, the city also suffered devastating epidemics, including a bout of cholera in 1832 that killed more than thirty-five hundred inhabitants.14 It was opportunity that lured people to New York, which had assumed a central role in commerce, responsible now for half of the imports and exports of the young nation. The 1825 completion of the Erie Canal, which linked the port city to the markets and agricultural resources of the interior, made lower Manhattan the new center of the country’s economy. Two majestic buildings devoted to this booming commerce—the United States Custom House and the Merchants’ Exchange building on Wall Street—were its principal landmarks.15

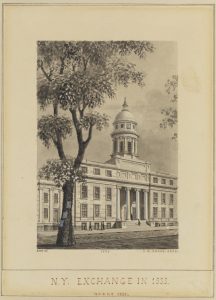

Centered in the financial heart of the city, the Great Fire began in the dry goods store of Comstock & Andrews on Merchant Street at about nine o’clock in the evening and consumed an entire block in less than half an hour. Strong winds fueled the fire; it spread and burned for fifteen hours.16 An antiquated water system, coupled with subzero temperatures that froze the fire hoses, hindered efforts to extinguish it. In the end, the blaze decimated the Financial District, reducing to rubble more than seven hundred buildings, with damages estimated at $20 million. At first, observers believed that the fire would not reach the Merchants’ Exchange, “the pride of [the] city and country.”17 Built in 1827 at a cost of $100,000, the luxurious structure housed mercantile offices, a post office, an auction hall, the Chamber of Commerce, and the New York Stock and Exchange Board (fig. 1). Eventually, however, the building succumbed to the flames, and its dome collapsed upon a fifteen-foot statue of Alexander Hamilton by Robert Ball Hughes (1804–68) that was recently installed there.18 Such was the fateful end of one of the most visible icons of the city’s prosperity, and with it the financial security of much of New York’s citizenry. As recorded in the New-York Spectator: “The arm of man was powerless; and many of our fellow citizens who retired to their pillows in affluence, were bankrupts [sic] on awaking.”19

The Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange print (fig. 2) isolates the notional epicenter of the destruction wrought by the fire. The emphasis in the print is without question on this building, on the scene of its alteration; its light marble façade and grand scale stand out against the surrounding objects and humanity. The print shows the façade of the Exchange from a slightly oblique angle so that the viewer can discern the ravaged interior of the once-imposing commercial center. On the side of the building, only the elevated basement and a jagged cutaway of the Hanover Street elevation remain. Fires continue to smolder within the building, as seen through the charred window openings, in structures behind it, and on either side. Only a small number of windows still hold glass, and the discrepancy between the empty frames and those that retain their glazing makes the vulnerability of the building palpable. Two hoses lie limply on the ground, expressing no water. Further down Hanover Street, where the flames are denser, a fire company operates a pump. Smoke billows into the sky.

The print confines the disaster within a literal and figurative frame: an emblematic moment is selected, when the fire is beginning to dissipate and the disaster has been contained. Its elements are more subdued, ordered, and rational. A tidy formation of soldiers proceeds down a reasonably clear street in front of the building. Firemen mill around in the alley, some engaged in conversation. A civilized group of onlookers, including children and at least one woman, has gathered quietly in front and to the right of the building. With the exception of an errant runner on the left, the people in the view divide between men performing their civic duty to put an end to the destruction and children and well-dressed spectators keeping a respectable distance from these worthy tasks. The unidentified figures appear not as individuals but instead as actors performing various roles (some of whom themselves watch a drama unfold before them) against meticulously wrought scenery itself reminiscent of a stage set.

Notably, almost no one faces out of the image; the inhabitants of the print and its viewer are therefore in a parallel position with respect to the event—both they and we are onlookers. But who, exactly, are the intended beholders of the Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange? Its price point serves as a useful guide.20 Currier and Ives’s own sales slogan—“Popular Cheap Prints’’—for the firm’s later productions points to the broad audience they came to serve.21 Evidence suggests that prints like this one would have sold for between 15¢ and 25¢ (between $4.06 and $6.77 when adjusted to today’s consumer price index), which was comfortably within the means of a middle-class buyer, if a bit more of a luxury for working-class individuals in the Northeast, who made 30¢ to 75¢ a day.22 In terms of the audience presented within the print itself, reading the print from upper left to lower right, the figures on which our eyes finally rest may be said to act as surrogates: they suggest that the primary implicit viewer of the image is likely middle class (or aspiring to be so). If imagined as having escaped the conflagration with at least the clothes on their backs, these figures may represent a glimmer of hope. The actors here—onlookers and workers—may also intimate behavioral cues: the image telegraphs composure in the face of crisis. Equanimity and sobriety are suggested as appropriate responses to the occasion. As the popularity of period advice manuals for the middle class suggests, knowing how to behave was in itself a source of comfort.23 Indeed, these manuals—meant in large part for young adults migrating to urban environments—gave copious advice on proper behavior. Particularly in the face of situations that challenged the characters of their readers, the manuals emphasized “flawless self-discipline.”24

In contrast to the relative serenity and orderliness of the Ruins print, the Herald paints a much more chaotic picture of the scene around the Merchants’ Exchange during the fire. An eyewitness who, by his account, appears to have arrived at the remains of the Exchange at a comparable moment to the one captured in the image, reports thick, sometimes impassable crowds of spectators and objects: “The street was full of people—the sidewalks encumbered with boxes, bales, bundles, desks, safes, and loose articles.”25 Despite the presence of “U.S. soldiers” at the nearby Phoenix Bank, “Boys, men, and women, of all colors, were stealing and pilfering as fast as they could.”26 While the image may authentically represent selected aspects of the scene, such as the firemen at a moment of relative calm, it conveniently relegates most of the unsavory details to some space beyond the frame. For example, New York firefighters of this period—all volunteers—were known to engage in street fights, to sabotage the firefighting efforts of rival companies, and even to refuse to work in the midst of emergencies for competitive or political ends.27 Currier, himself, became a member of one of these volunteer units by 1840, a biographical detail that may explain his penchant for incendiary events and his interest in portraying firemen in a positive light.28 The firm of Currier and Ives later issued numerous prints illustrating and, it has been suggested, idealizing firefighting and firemen, including the famous series The Life of a Fireman (1854–66), for which Currier himself probably served as the model, as in The American Fireman, Facing the Enemy, 1858 (fig. 3).29

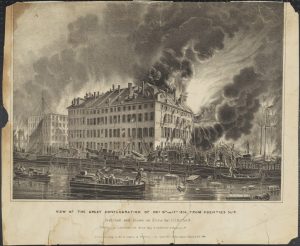

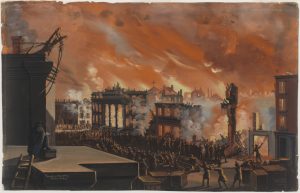

The lesser known View of the Great Conflagration of Dec 16th and 17th 1835; from Coenties Slip, 1836 (fig.4), also a Currier collaboration with Bufford and Disturnell, tends slightly more in the direction of the eyewitness report from the Herald. Whereas Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange is both ominous and comforting in equal measure, the view of Coenties Slip is more generally descriptive. The latter represents a distinctly different, earlier moment in the course of the fire—one showing a climactic moment as opposed to the denouement of the Ruins. In this print, the dark, immense columns of smoke billowing skyward make the combustion seem more threatening, although, at this arrested moment, the building is still intact and may be saved. Compared to the stillness of the Ruins, the emphasis of Coenties Slip is on the strenuous efforts of people to recuperate the potential losses of the fire. Here figures heave bundles of goods out of the windows of a burning building and into the water in a desperate attempt to save the merchandise stored in these warehouses, stockpiled with riches from around the world. While firefighters and engines are visible, they blend into a large crowd of indistinguishable people who have gathered at the base of the building. In its tone and message, Coenties Slip is more ambiguous than the Ruins print. A sense of civic order is replaced by a chaotic jumble of humanity, while in the burning building above, we discern individual figures risking their lives to save goods from a burning commercial building. From the safety of boats, men watch the pyrotechnics and collect the merchandise floating by.30 Are they merchants retrieving their wares? Thieves? Can these losses be recuperated? The print leaves such questions open. Without the civic iconography of the Ruins and its subtle moralizing message, the Coenties Slip view of a private building and property may have seemed too equivocal to period viewers, which may explain its lower survival rate and relegation to an obscure corner of Currier’s history.

Although many have noted the speed with which Currier produced his prints of the fire, the disaster sparked the imaginations of other image makers at the time; a comparison of their work to Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange underscores what is unique about this work. Views by other makers—all of which seem to postdate the publication of Currier’s print—address different audiences and take a divergent approach to their modulation of sensation. Like Coenties Slip, several show the event at or near its dramatic peak, but in, for example, Henry R. Robinson’s lithographic rendition (fig. 5), flames burst dangerously toward spectators (and viewers). In contrast to the rational decorum of the personnel in the Ruins, here the figures, pointing in all directions, give an impression of confusion and agitation; a gathering of prominent citizens in the middle foreground, their dark coats contrasting with the fire, create a focal point in the print. Indeed, Robinson’s approach may have appealed to his specialized clientele, who seem to have had an even more keen appetite for sensationalism and celebrity than Currier’s audience.31

The fire so captured the attention of Nicolino Calyo (1799–1884)—best known as a gouache artist—that he painted twenty-two original large-scale color views of the event from 1835 to 1840. Born to an aristocratic family, Calyo studied at the Royal Academy of Naples, where he was taught the traditional Claudian formula for painting a landscape. After traveling extensively throughout Europe, Calyo arrived in the United States around 1834—his first stop was most likely Baltimore—and he settled in New York the following year.32 His academic European approach reveals itself in a comparison with the Ruins image. Many of Calyo’s several views in gouache present the fire at its height (fig. 6). Calyo, who exhibited his work Eruption of Vesuvius along with other works in Baltimore in 1835, approaches the New World event as an epic narrative.33 He trades on eighteenth-century conventions of the sublime—diminutive figures dwarfed by the grand panoramic scale of the scene, for instance, and dramatic contrasts of light and dark—employed in such works as The Eruption of Mount Vesuvius (1877) by French painter Pierre-Jacques Volaire (1727–99), who visited Naples in 1768 and likely inspired Calyo’s own iteration of the same event.34 Such academic conventions would have appealed to the artist’s more sophisticated, well-to-do audiences, who could afford the higher prices of original paintings and would appreciate the deployment of established pictorial recipes.35 Calyo’s Great Fire portrayals could take their place within a long line of legendary disasters—a line that included his English contemporary John Martin (1789–1854)—in which the particular locale is secondary to the universal sublimity of the tragedy.

In its composition and specificity of location, the Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange has more in common with an architectural print. Such works recorded an architecturally or historically important edifice and were common to early American printmaking. Architectural prints were produced throughout the nineteenth century.36 An image of the United States Custom House later disseminated by Disturnell illustrates this style (fig. 7). Distant from the high-art pretensions of Calyo, the architectural print convention gives the Ruins a particularly tangible, regional reality. Yet it upends the logic of its prototype by tacitly casting itself as the “after” to the architectural print’s “before.” Whether the viewer had seen renderings of the Merchants’ Exchange or not, the implied analogue gives the reader imaginative access to both states, effectively intensifying the pathos of the image.

Where the Calyo works and the Ruins lithograph do share commonality is in some of the formal properties of their respective mediums. No longer tethered to the severe linearity of engravings, lithography facilitated a lighter touch and offered the artist more subtle chiaroscuro, in this regard closer to painting or watercolor than the hatching and striations of intaglio processes. Indeed, these evocative, tonal qualities plant Currier’s print firmly in the Romantic mode. Compared to the average engraving, the softer tones of lithography were better able to play on sensibilities and open up an imaginative terrain for the viewer. Dark and light are more continuous, autographic, and nuanced in the lithograph, as are, perhaps, their moral and psychological correlatives, facilitating a complex emotional response.

Historically speaking, lithography also blurred the lines between high and low culture—it was a democratizing mass medium that made more visual information available to more people. In this way, it was closely connected to the recently established “penny press,” without which the Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange print might not have been possible. Compared to the mainly political and economic orientation of the established (and expensive) upper-class subscription papers, the new penny press sold on demand in the streets and pursued human-interest stories that played to the emotional responses of its readership. The editor of the New York Sun—one of the first of these publications, launched in 1833—stated:

We newspaper people thrive best on the calamities of others. Give us one of your real Moscow fires, or your Waterloo battlefields; let a Napoleon be dashing with his legions throughout the world, overturning the thrones of a thousand years and deluging the world with blood and tears; and then we of the types are in our glory.37

The Sun, along with the Daily Transcript, founded shortly afterward, and the Herald, established in 1835, competed for the attention of the common citizen—the implicit audience for the Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange and later, the explicit audience for the Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound.38 By 1835 the circulation of the Daily Transcript and the Sun hovered around ten thousand each, greatly eclipsing that of the eleven mercantile journals in New York, which only claimed about seventeen hundred subscribers per paper.39 The style and content of the penny papers responded to the egalitarian leanings of Jacksonian democracy, which coincided with a new era of accessibility to information and, with it, a greater degree of transparency.40 During the banking crisis of 1837, for instance, Herald editor James Gordon Bennett (in a clearly self-serving manner) publicly insists that the engineers of the then proposed scheme to cease specie payments should speak to the people in a way they would understand. He admonished them to avoid couching the plan in the impenetrable language of the upper-crust mercantile papers.41 Likewise, Currier’s prints made newsworthy events visible on a wide scale and in a visual vocabulary that was accessible and acceptable to this new class of consumers.

Despite their congruencies, prints and newspapers in 1835 diverged in some essential ways. The first job of the newspapers was reportage, and these publications carried text-dense, profusely detailed accounts of all aspects of the fire. Journalists could perform several tasks that were not easily handled by an illustration alone: they could specify how and where the fire spread and the weather conditions that facilitated it, quantify the losses in buildings and dollars, list the merchants affected, seek out causes and responsible parties, and offer observations that would otherwise be difficult to visualize. We are able, for example, to make sense of the unused hoses lying on the ground in the Ruins lithograph from the Herald’s reports about the extreme cold, as a result of which “the hose of the fire engines was run along the street and frozen” in the subzero conditions.42 News stories could also delve into the more distasteful aspects of the event—such as looting—that image makers at the time seem inclined to avoid.

Moreover, newspaper texts and the newly emerging visual culture of lithography employed different rhetorical strategies. Whereas the newspaper accounts made liberal use of hyperbole and bombarded readers with a surfeit of detail, the Ruins print relied on suggestion and editorial economy. In a point-by-point comparison to the news reports, the Currier-Bufford-Disturnell rendition of the print appears more staged, a selective fiction and not an actual snapshot of the scene.44 Like any good realist fiction, the print created a convincing verisimilitude. Indeed, the Ruins worked upon its viewers through a series of imperceptible effects. Instead of trying to capture the whole fire, for example, the print employed something like the literary device of synecdoche—the remaining fragments of the building allude to the former structure and from there to the totality of the social, economic, and psychic tolls of the fire, inviting viewers to fill in the implications with their imaginations. Romanticism embraced the ruin in just these terms, arguing that what is fragmentary and suggested, but not specified, is even more emotionally and psychologically powerful than what is visible or spelled out. The durable quality of the print—in this regard more like a novel than a disposable newspaper—allowed readers to return again and again to this idealizing version of the story or, more boldly stated, of history. Insofar as viewers derive pleasure from such an exercise of the imagination, the print rewarded repeated exposure. People possessing the Ruins print could come back to this compelling representational space long after the daily news had been discarded.

That said, we do not know exactly how prints such as the Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange were used or, in fact, how long they were kept by their purchasers. These prints seem to have had some life after the initial news story; Robinson’s advertisements for his print of the “Great Conflagration” continued at least until well into August of the next year.45 In terms of how the prints may have been displayed, the evidence is only circumstantial. The later Currier and Ives firm once suggested its prints might be used for the “ornamenting of walls . . . the backs of bird cages, clock fronts, or any other place where elegant tasteful decoration is required.”46 A large selection of the later Currier and Ives prints were well-suited to adorn nineteenth-century parlors, but whether newsworthy prints like the Ruins would have constituted tasteful decoration in this domestic setting is debatable. As a place most often characterized as a sanctuary, the Victorian home and its peace-preserving walls may not have been an ideal locale for a print of a calamity. Conversely, the genteel, palliating representation of the fire conveyed in the Ruins print might have increased its eligibility for domestic decoration; its makers may have been mindful of this possibility when designing the image.47 We may certainly imagine the prints adorning firehouses—sometimes extravagant structures with dining rooms, drawing rooms, and libraries—barrooms, hotels, barbershops, and other businesses (firefighting prints were promoted to and even used as advertisements for insurance companies), and, perhaps, schoolrooms.48 They may have even found their way into Victorian scrapbooks or albums, becoming an expression of an individual’s identity that could be shared with guests and family members. In these latter viewing conditions—while different from those of a framed illustration—middle-class codes of conduct would have still demanded some delicacy in the treatment of the print’s subject matter.49

One possible use of the disaster prints was as memorialization. In this light, the decision to cast the remains as ruins was not without its cultural implications. Ruins held an abiding attraction in the Euro-American Romantic period and after, with their nearly universal power to elicit a pleasurable melancholy and ruminations on the destiny of civilizations. In keeping with the portrayal of the print, the Herald called the remains of the Merchants’ Exchange “magnificent” and “uncommonly picturesque.”50 The notion of ruins was closely linked in at least some writers’ minds with the historical and the monumental, at a time when the still fledgling republic lacked both history and monuments. As if in compensation, the Herald entered its Great Fire in a strangely morbid competition even before the smoke had cleared:

We recorded in our paper of yesterday, the first stage of one of the most awful conflagrations that ever befell any city, in any age, or in any country. Talk not to us of the burning of Moscow—the property there lost was nothing in comparison to that yesterday in New York. The great fire in London is equally unimportant.51

For all of its terrible devastation, at least the fire gave New Yorkers a major event to register in the annals of their incipient history. The Sun augments the historical significance of the fire by connecting it directly with an image of iconic, time-honored ruins: “The merchants of the First Ward, like Marius in the ruins of Carthage, sit with melancholy moans, gazing at the graves of their fortunes, and the mournful mementoes of the dreadful devastation that reigns,” a reference, no doubt, to Marius amid the Ruins of Carthage (1832) by John Vanderlyn (1775–1852), which was exhibited at the rotunda built for the purpose in 1818–19 on Chambers Street, near City Hall Park.52 Ruins occasion meditation on time and fate; the Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange acted as a palimpsest, inscribing the present over the past and allowing the viewer to simultaneously consider what is and what was.

Viewing this representation of the fire could evoke a series of disparate emotions, among them awe and idealism, along with grief and anxiety. Some entrepreneurs and developers may have been able to see the outlines of a profitably reconstructed business district in the ashes of the fire. Indeed, within a year, a more vibrant, majestic city center replaced the old one as five hundred grander buildings lined the now wider streets, with significant profits accruing to many merchants, as well as to the authors of this improved metropolis.53 From a broad perspective, substantial evidence supports the idea of an American ethos of creative destruction and regeneration throughout the country’s history.54 And we cannot overlook what Currier, Bufford, and Disturnell might have imagined as the immediate dividends of the fire print for their businesses. Some period writers simultaneously bemoaned the immense devastation of the fire and primed the citizens of New York with pep talks on revival: “We possess here, life, strength, energy, enterprise, and every animal and mental power to rise above the awful catastrophe. . . . Cheer up fellow citizens—cheer up. We must recover it in a couple of years.”55

Nonetheless, at the time the print was made, many sources reveal a general uneasiness about the future. As Kevin Rozario notes, “Businessmen were not yet conditioned to see the economic opportunity in the ruins.”56 This period was also rife with news reports and sermons that betrayed anxieties about moral decay and irreparable destruction and suggestions that Providence may either capriciously or intentionally rain down devastation on the republic and its citizens. After the fire, responses included hand-wringers worrying that New York would fall behind in the ever-important race with other urban centers.57 Some speakers and writers felt that the disaster rendered oxymoronic the idea of “financial stability”—whether individual or national. Historian Fred Somkin suggests that many antebellum Americans despaired that their prosperity would, ironically, precipitate their own demise. He cites the diatribes of numerous speakers and writers on this subject, concluding that, “The essential fragility of civilization and its liability to instantaneous and utter destruction were themes constantly reiterated, as if in a new theology of prosperity.”58 One of the many sermons delivered after the fire echoes the idea that the financial success of New York literally and symbolically carried the seeds of destruction: “The very merchandize [sic], from which industry and enterprise make their gain, can easily be turned by God into fuel.”59 Likewise, the Sun offers this discernment:

Where but thirty hours since was the rich and prosperous theater of a great and productive commerce, where enterprise and wealth energized with bold and commanding efforts, now sits despondency in sackcloth . . . It seemed as if God were running in his anger and sweeping away with the besom of his wrath the proudest monuments of man.60

As it turns out, these Americans had good reason to fear that the other shoe was going to drop. Within a year and a half, a loss of faith in banks and the rampant speculation endemic to Jacksonian policies (continued under Martin Van Buren) led to the Panic of 1837, which thrust the country into a five-year depression.

Compounding these specific financial uncertainties, citizens in this era were often subject to other kinds of psychic afflictions, brought on by a new social mobility and actual physical mobility. Karen Halttunen suggests that middle-class Americans were suspended in a “liminal” state as they transitioned in great numbers from rural to urban life and as socioeconomic definitions became more fluid: “By the 1830s, middle class no longer meant a point of equilibrium between two other fixed classes; to be middle class was to be, in theory, without fixed social status.”61 If the idea of impending ruination raised by sermons, newspaper stories, and a superabundance of behavioral instruction is any indication, this liminal state would have suspended many Americans between social and economic statuses, between virtue and debasement, security and desperation.62 Currier and Bufford were two such Americans without fixed social status—two young men who had recently arrived in the big city and established speculative businesses within spitting distance of a devastating fire that threw the future hopes of the metropolis into chaos.

Two concomitant strains—prosperity and calamity—manifest in the tensions of the Ruins print, which gives voice to these fears and also serves as a rejoinder to them. If transience and upheaval made Americans yearn for greater “fixity,” as Halttunen suggests, the print fixed in the mind’s eye a moment in which audiences could indulge in the emotional and aesthetic valence of such a spectacle, while the carefully orchestrated imagery offered a way to negotiate not only this disaster but, in a sense, any potential disaster that might arise, putting the idea of salvation just within reach.63

Dreadful Wrecks: Drama at Sea

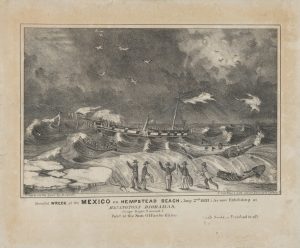

The first print of a shipwreck bearing Currier’s name was produced in 1837, a small folio print of 6 ½ by 9 7/8 inches. This image is rarely mentioned in the literature on Currier and Ives. Drawn “on the spot by artist H. Sewell,” the Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico on Hempstead Beach. Jany. 2nd 1837, 1837 (fig. 9) records the fate of a sailing ship from Liverpool that foundered in a snowstorm off Long Island while waiting for the arrival of a pilot from New York to guide her into port.64 Of the 116 or so people on board, only 8 were rescued. People who assembled on the beach could see the stricken ship but were unable to render assistance because of the high waves, which also capsized the lifeboat. One small craft made it to the ship and rescued eight passengers, although conditions made it too dangerous to return for more.65 Bystanders witnessed a horrific scene in which for “18 hours [the victims’] piteous cries and shrieks were heard upon the beach.”66 The lithographic rendering of this event that soon issued from Currier’s press had to modulate the drama for middle-class sensibilities and likely taught the fledgling entrepreneur invaluable lessons about his potential audiences and how to address them.

The Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico shows the vessel demasted (which was done by the crew to steady the hull), covered in icicles, and full of despairing people. On the left side of the print, a boat makes its way to shore—probably the rescue vehicle. On the right, two people—still alive—flail in the water. A ghostly section of a sail flies aloft toward dry land. Front and center, helpful people handle ropes, presumably as part of the rescue effort. Finally, in the lower right foreground, below the fallen mast, rests the skeleton of a small boat—possibly the lifeboat destroyed by the heavy surf—foreshadowing the fate of the passengers in the next few hours.

Here again, the visual presentation and the newspaper coverage parted ways. Descriptions of the dead—often graphic and horrific—regularly appeared in news accounts. The New York Courier and Enquirer (a newspaper with a primarily political and business bent) reported: “The next morning the bodies of many of the unhappy creatures were seen lashed to different parts of the wreck embedded in ice.”67 In its characteristically sensational aspect, the Herald takes this one step further, describing bodies from the wreck that washed up on the beach “bruised, blackened, and mangled.”68 In the Dreadful Wreck, bodies receive less attention than the scene of the disaster and the wrecked craft. Dead bodies almost never appear in these representations—a distinction that has significant consequences for interpretations of the later print of the Lexington.

In place of a post-facto inventory of the dead, the Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico substitutes the high drama of the attempted rescue. It picks up the action at a point similar to that of Coenties Slip, as the disaster unfolds and when salvation is still possible, but here the frantic activity is clearly toward moral ends, as the characters scramble to help the victims of the wreck. Roiling seas literally tower over the figures in the foreground; wild waves amid imposing blocks of ice replace the calm of the waters around Coenties Slip, where the extreme cold leaves no visual evidence. Moreover, the viewer is situated not at a distance from the action but immediately on the beach with the rescue crew, unshielded from violent natural forces. These characters are no longer keeping watch, nor are they detached middle-class viewers; they are coming to the aid of sufferers. Like the Ruins, though, the print pits the tragedy of the scene against elements of consolation—the notions of proper behavior (frequently reiterated in the news stories about the rescue efforts). With people alive on the ship and on the lifeboats, we may yet entertain the illusion of hope. The moody atmosphere and romantic symbolism of spectral sails and skeletal lifeboats—once again facilitated by the tonal capabilities of lithography—contribute to the drama and fearsomeness of the view and foretell the impending disaster. Comparable to the ethos of the Ruins, the tonality also softens the blow, allowing the disturbing atmospheric elements to work on the audience in a genteel and almost allegorical manner—even the torn sails taking flight on the wind find their correlative in birds circling the heavens. If the Ruins resembles a stage set, the dramaturgy of the Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico separates us emotionally from actual death and destruction. The flattened perspective situates the foreground band of rescuers unnaturally close to the doomed ship, thus formally comprising two stable parallel registers, emphasizing the idea of actors performing against theatrical scenery.

As it happens, a version of the Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico did play a part in a theatrical performance.69 The caption on the print indicates this image was “Exhibiting at Haningtons Dioramas.” Where Currier’s earlier productions were essentially copublished with penny press newspaper stories, here the print worked symbiotically with another form of popular entertainment, one that also looked to both epic stories and sensational newsworthy subjects (often disasters) to attract an audience. Hanington’s “Dioramic Institute,” installed at the City Saloon on Broadway, was one of the commercial moving dioramas of the day. It offered spectacles in which, for 12 1/2¢ to 50¢—the same general price affixed to many of Currier’s prints—audiences could experience events and scenes staged as enlarged paintings on screens.70 Attached to giant rollers, the scenes unfurled past observers, accompanied by narration—and, in Hanington’s case, very loud sound effects and music.71 These works filled one’s visual field in a protocinematic fashion and employed every available sensory device (including explosives) to produce maximum dramatic effect. Hanington’s delighted audiences with “performances” of such historical subjects as “The Conflagration of Moscow,” biblical scenes such as “The Deluge,” and more contemporary disasters, such as the wreck of the Mexico and the Great Fire. The precedent for these “mechanical theaters,” according to Erkki Huhtamo, was the baroque theater, “a kind of viewing machine, a system for presenting scenic illusions.” Notably, as in Currier’s disaster images, scenery became a primary actor in this period: “Tensions developed between spectacular sets and the human presence. Actors were increasingly seen as elements of the scenic view.”72

A notice about the New York diorama show Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico first appears in the Herald on January 9, 1837, indicating that a mere week after the event, the disaster had already been transformed from headline into theater. This instructive notice indicates how viewers were meant to respond to this image: “The loss of the barque Mexico will be faithfully represented in Hanington’s Moving Dioramas this evening . . . will form a scene of the most intense, although melancholy interest.”73 At the diorama presentation, the audience could experience all of the emotions attendant to such an event at the remove provided by theatrical spectacle, where “intense” interest is sanctioned and melancholic responses are prescribed. Another advertisement in the Herald for Hanington’s, repeated every couple of days from January 11 through March 25, 1837, attempts to describe (and augment) the audience for the “Shipwreck of the Mexico”: “The faithful representations of this melancholy event having created the most intense interest to a very large and fashionable audience, on its first representation, it will be repeated this evening.”74 In fact, the sheer volume of the sound effects and music, as reported by neighbors, suggests that an audience seeking subtle, refined entertainment would likely look elsewhere.75 Along these lines, Huhtamo confirms the diversity of audience for these productions: “Moving panorama shows attracted a more heterogeneous clientele by combining the seductive popular culture with assurances of their moral quality, suitable for anyone irrespective of religious or political stance, gender, or age.”76 The moving dioramas of Hanington’s employed many of the same tactics as Currier’s disaster prints, with both promoting a democratic art form that elicited a strong response.

The Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico print is most likely a smaller version of the same scene drawn at large scale for the diorama; Sewell, its draftsman, was touted as one of the “best artists” working for Hanington’s.77 The Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico must have appeared within the two-month span of the advertisement, as the “now appearing” subtitle indicates. The print may have been available as a keepsake for people who had seen the diorama presentation, served as an advertisement to lure people to Hanington’s, or functioned as a stand-alone print, or perhaps all three.78 Its departure from the newspaper accounts and connection to the highly dramatic dioramas underscore its audience’s taste for a certain kind of theatricality: a desire less for actuality than for dramatic enhancement and sensory amplification. Hanington’s performance was ephemeral, however, while the print could endure. The print allowed viewers to process the disaster on their own terms in the privacy of their homes, as opposed to the stage-managed and often cacophonous public atmosphere of the dioramic theater, which was not conducive to reverie or quiet contemplation.

While they share a basis in theater, the mediums diverged in other ways. The narrative nature and physical conditions of the diorama encouraged the audience’s perhaps baser desire for a sensational experience in the dark. The print, seen in the more sober light of day and in its static, quiet, genteel representation of do-gooders, celebrated virtuous behavior and restraint in the face of disaster. Hanington’s advertisement for the Mexico diorama illustrates the gap between the mediums. It gives a blow-by-blow description of how the action will unfold in a series of scenes—from the first “appearance of the Mexico” to “firing distress guns during the tempestuous night” to the “cheerless appearance at daybreak—the rigging covered with ice.”79 By contrast, the one part of the diorama narrative selected for the Currier print, while offering a moment of high drama, precedes the worst of the tragedy in which (the Hanington’s advertisement boasted) the ship is “finally sinking and bilging on Hempstead Beach” and, we presume, the majority of the passengers have surrendered their lives.80

“Solemn Proof of the Uncertainty of Life”

Currier could not have mistaken the potential of this kind of image or failed to recognize the hallmarks of Hanington’s success.81 Nor did Benjamin H. Day, owner of the Sun, also known for his audience-arousing tactics and the publisher of record for the Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico print. Indeed, this connection between Currier and the Sun may well have set the precedent for the collaboration that resulted in the wildly successful print Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound, 1840. This print marks an evolution in Currier’s understanding of his audience and in his marketing techniques. It entered into circulation in an unprecedented manner for a lithograph and represents a new threshold in Currier’s developing sense of how to balance sensation and decorum. In addition, the Lexington image gives form to antebellum attitudes toward technology, greed, fate, mortality, and consolation, thus providing viewers with a scaffold for multivalent responses.

As the story goes, Currier was in the offices of the Sun when news of the Lexington disaster reached the newspaper. The Sun’s management (Moses Beach, brother-in-law of founder Benjamin Day, was the owner at this time) and the lithographer must have immediately recognized its significance and sought to capitalize on its potential interest for audiences.82 With all dispatch, artist William K. Hewitt was commissioned to draw the scene, and together the Sun and N. Currier Lithographer launched the shipwreck image that secured the printmaker’s national fame.

If the Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico rolled by enthralled audiences for more than two months, the Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound trumped the former shipwreck on several fronts. Also in the dead of winter, the Lexington disaster involved a massive fire that demanded of its 140 victims a terrible choice between burning on board or freezing to death in the icy waters of Long Island Sound. It was sparked by the incautious choice, driven by profit motives, of transporting a flammable commodity—cotton—too near the hot smokestack of a ship carrying passengers and by the fitting of blowers on the boilers that overheated the stacks. It sent to the bottom of the sea the very popular vessel—of revolutionary speed and design—personally commissioned by rising transportation magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt and launched only five years before.83 The grand 205-foot Lexington, built at a price tag of $75,000, went down in a blaze in the middle of a nationwide economic depression.

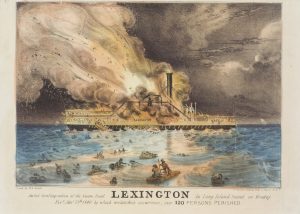

The Lexington wreck appeared in newspapers across the country and generated a great body of literature, including sermons, poetry, and children’s books.84 It also spawned a number of lithographic prints. Perhaps because of Currier’s speed in bringing it to market, its novel pairing directly with newsprint, the print’s aesthetic choices—or all of the above—the image became the “most widely distributed news picture of its generation.”85 Currier, who continued to sell the print eleven months after its publication, issued at least four versions of the Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound that vary in size from about 8.5 by 12 inches to 23 by 16 inches.86 The Sun originally published the print in black and white (fig. 10), but Currier offered a hand-colored version soon after (fig. 11).87

In the image, the fire raging in the center of the ship sends copious flames and smoke into the sky toward the left side of the composition. The clouds and moon in the night sky on the right side of the print add a menacing element. Minute figures crowd the decks of the ship, some hurling themselves into the water. One person appears to be throwing a cotton bale off the transom, probably to use as a flotation device. Remnants of the two scuttled lifeboats are half-sunken in the water near the wheel. In the foreground, people float directly in the water or on cotton bales—the very instruments of the fire and their demise—with some calling for help and some aiding others; one person low in the water may be dead. In the right middle ground, we can make out a sail, no doubt on the sloop Improvement that we later learn could have rescued the passengers but uncharitably turned away from their troubles.

Relative to the overall mood of calm and control of the Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange and even the drama of the Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico, the Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound exhibits a heightened theatricality—it combines elements of the earlier prints in a way at once more spectacular and sublime. Like the previous two images, it deploys a sort of stagecraft through its emphasis on elaborate scenery and its relative de-emphasis of the victims. The moment illustrated by the print is when the fires burn at their highest but the ship remains afloat and the people in the water are still alive—a dramatic pinnacle. The brooding romanticism of the sky of the Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico returns, but here it is violently interrupted by a great plume of flame and smoke. In a horrible echo of Coenties Slip, people throw their own bodies out of the burning structure along with the goods; human salvation is the priority. At the same time, the Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound still insists on propriety. The man on the raft in the foreground—the most discernible figure—seems to be wearing fine clothes, and he and other men in the image have wondrously maintained their top hats in rough seas or after casting themselves into the water. The charity and moral behavior of earlier prints persist, as people try to help each other onto the floating debris. We see no tide of corpses, and the renderings of the victims are so hazily sketched that we do not encounter burned, frozen, or injured bodies. High art in this period may not have shied away from lifeless bodies transformed by death, but popular disaster prints by such makers as Currier and his contemporaries approached this subject with circumspection.

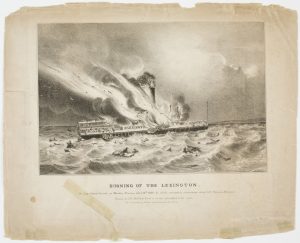

Aside from its fairly unique placement within newspaper text, Currier’s representation of the Lexington disaster differs to greater and lesser degrees from the many renditions by others that followed.88 Speed may have been the main advantage, but the particular balance of drama and potential deliverance of the Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound may have been another. Bufford published his own lesser-known version of the event (fig. 12).89 More professional than Hewitt’s rendering, Bufford’s portrayal is also tamer and not as arresting. The ship, listing at a slight angle toward its aft, appears less solid and imposing, and the flames and smoke seem elegantly linear and less histrionic. Lithographer Daniel Wright Kellogg, of Hartford, Connecticut, produced a print—a very close copy of the Hewitt—that de-emphasizes the drama of the fire and smoke; the latter blends almost seamlessly with the clouds in the sky, and the people in the water are now indistinct outlines. A French lithographer conveys a rather fanciful version of the ship that most closely approximates the style of English artist J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851) (fig. 13).90

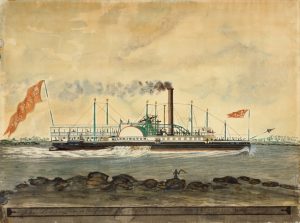

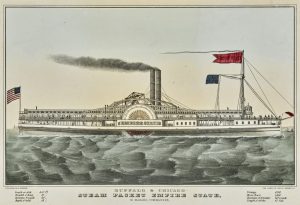

Currier’s wrecks, instead, heed the conventions of the ship portrait genre, works often commissioned tocoincide with the launch of a new vessel. The American fascination with the new steamship technology explains the proliferation of these images; Currier and Ives eventually issued two hundred separate portraits of these marvels of maritime technology.91 In such images, the ship, shown in profile, fills much of the composition, neatly bifurcating sea and sky, as in the painting of the Lexington made by maritime painters James (1815–97) and John Bard (1815–56), sometime after 1835, and Currier’s print Buffalo & Chicago Steam Packet Empire State, 1845 (figs. 14 and 15).92 Like the buried trope of the architectural print in the Ruins, borrowing the composition of the ship portrait for a shipwreck image would likely evoke an awareness of before-and-after conditions. This tacit comparison invites a reckoning of fate and, in the case of the Lexington, of pride and failure: how quickly the mighty fall, the stricken behemoth declares.

Pride and failure were keynotes in the jury inquest, which was held immediately after the accident. In his testimony, Cornelius Vanderbilt attested to the seaworthiness of the ship. The defenders of the Lexington mention the quality of the wood and the fittings, the character of the builders, and many other specifics. Newspaper reports on the inquest repeat a common theme of reports of steamship accidents: blame must be assigned. In subsequent news stories, issues emerge about the reckless behavior of the crew, the negligence of the inspection authorities, the heartless decision to sail on made by the captain of the Improvement, and the questionable choice of carrying cotton on a passenger vessel; without the promise of the dividends from said cotton, it should be noted, Vanderbilt probably would not have commissioned the ship.93 The final verdict of the inquest reported in the Herald on February 1, 1840, condemned the steamboat inspectors, as well as the directors of the company, for their negligence, citing the latter for the “odious practice of carrying cotton on passenger boats, in a manner in which they are liable to take fire.”94

Newspaper accounts of steamboat accidents primarily sought recourse to human error and not to the technology itself. Americans had a fraught relationship with recent innovations in transportation technology, such as the steam-powered ship and the railroad.95 They were enamored of these new technologies despite the possibility of a new kind of mass and gruesome death, with steamship explosions among the most often cited contributors to deadly accidents.96 The glory of steamships rested in their awe-inspiring power and speed, collapsing time and opening new ports of travel and adventure. On an economic level, they allowed the transportation of goods on a greatly enlarged scale. It appears that the fascination with steam power produced in travelers a kind of amnesia about the many reports of accidents. According to one writer who published her western journeys in 1850 with a section titled “Steamboat Disasters”: “I do not think that it ever occurred to any of our cheerful little party that they ought to be nervous, or that we ever called to mind the perils by which we were surrounded.”97 By contrast, some travelers did not lose sight of the risks, including Charles Dickens, who in his 1840 American Notes for General Circulation announced: “It always conveyed that kind of feeling to me which I should be likely to experience, I think, if I had lodgings on the first floor of a [gun]powder mill.”98 Likewise in analyzing the accounts of steamboat accidents in the 1856 Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory and Disasters on the Western Waters, historian Walter Johnson notes that the extensive registers of the dead contained therein combined with current information about the Mississippi Valley “at once signaled the underlying dangers of the steamboat economy, unstably contained them within its ‘history,’ and reaffirmed a shared commitment to that economy through a sort of remembering (the dead) that was also forgetting (the danger).”99

Americans, however willing to accept the risks of steamboat travel, did faithfully commemorate accidents through a host of cultural forms. Books on disasters at sea were published in 1834, 1836, 1846, and 1856; a raft of music sheets appeared; and even a child’s jigsaw puzzle titled Blown Up Steamboat was produced.100 Many of the news accounts of the period expressed the admixture of horror and fascination at the sight of catastrophic technological failure, including one firsthand story of an explosion that resulted in a man “who presented a most shocking and affecting spectacle; his face was entirely black—his body without a particle of skin. He had been flayed alive.” In this same account, this passenger then offers a striking rationale of the technology, focusing on human inventiveness even in the face of the most horrific human tragedy: “I went to examine that part of the boat where the boiler had bust. It was a complete wreck—a picture of destruction. It bore ample testimony of the tremendous force of that power which the ingenuity of man has brought to his aid.”101

These gruesome tales indicate a certain appetite in the audiences who consumed them, which might also help account for the increased sensationalism of the Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound print relative to Currier’s earlier efforts. Its attention to the mass suffering of its victims may be linked to a still evolving idea of pain in this era, particularly with respect to spectatorship. It has been argued that the sensationalism of the penny press was an outgrowth of the earlier “culture of sensibility,” which was characterized by a form of sympathy that blended what historian Karen Halttunen terms “vicarious pain” with readerly pleasure.102 As early as 1800, William Wordsworth bemoaned the fact that urbanization and improved communication technology had cultivated an increased desire of the public to be astonished and excited, as long as the spectator could do so safely.103 The concept of safety is again key to appreciating Currier’s Lexington representation. We are close to the civilized victims in the foreground but far from the fire, the turmoil aboard the ship, the frantic desperation of the passengers casting themselves into the water. The audience cannot fail to notice this terrible desperation, this pain, but the Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound does not assault viewers with it. A closer or more detailed view might have pushed the image into taboo territory.104

Equal in importance to the understanding of sensationalism and its appeals are Victorian attitudes toward death and dying. Americans were preoccupied with their bodies and their souls in this period, as evidenced by a surfeit of songs, poems, sermons, and novels about death and how to deal with it—“consolation literature”—which flooded the consumer market.105 Many theories have attempted to account for this widespread phenomenon. Some suggest that rising mortality rates help explain the preoccupation; one historian documents a net decrease in lifespan from 1790 to 1860.106 High infant or childhood mortality rates and death in childbirth were real enough, but awareness of the consequences of pandemics, natural disasters, and large-scale accidents resulting from new transportation technologies may have been magnified in the public mind by the communal nature of city life: urban density made large-scale death from a common source more possible and more conspicuous.

In this light, the wreck of the Lexington may have served as a memento mori to many—an image in the service of remembering not only the life and death of its victims, but the life and death of the viewer.107 Such awareness was ubiquitous in private journals, such as this 1840s example: “Oh how uncertain is life, and yet man [sic] live quite as heedless as though their life was guaranteed to them.”108 This unidentified author writes about the urgency of preparing for death, a sentiment constantly reiterated in a pamphlet published shortly after the tragedy of the Lexington. Its title, A Warning Voice from a Watery Grave! . . . Or a Solemn Proof of the Uncertainty of Life, and Importance of an Early Preparation for Death! In the Instance of the Melancholy and Untimely Fate of the Much Esteemed and Lamented Miss Sophia W. Wheeler, Who Was One of the Many Unfortunate Victims Who Perished by the Awful Conflagration on Board the Ill-fated Steamboat Lexington, on Her Passage from New-York to Stonington, Jan. 13, 1840, effectively sums up its contents, which exhort readers—especially younger ones—to live a good Christian life before parting this mortal coil. The tract employs a revealing selection of metaphors that reinforce both the powerful symbolism of primordial forces and the vicissitudes of fate. The unnamed author speaks of the “cold icy arms of death,” likens time to a “long flowing stream,” and describes life as a “dubious navigation.”109 The writer also paints a macabre picture of the victims at the bottom of the sea:

And could we but have an internal view of that watery sepulcher, where lies still buried so many of the lifeless bodies of those who but yesterday were in active life, with the fond expectation, perhaps, of participating in the enjoyments thereof, what a spectacle should we there behold—the melancholy, if not frightful remains of that amiable and beloved daughter, so late fair and gay, and whose sudden and unexpected exit at this very minute probably wrings the heart and moistens the eyes of her afflicted parents! . . . And there might we behold the remains of that tender beloved infant, so late prized above all price, by that affectionate mother, whose cold and inanimate body still lies by its side, or, perhaps, with it still pressed to her bosom, as if unwilling to be separated from her precious charge, even in death!110

While the author of that particular pamphlet suggests it is “gain for the Christian to die, however sudden and unexpected his or her death,” most of the widely circulated consolation literature penned for middle-class audiences at the time would lead to a different conclusion.111 These materials made manifest the value of a “good death,” a concept that dates to medieval times but was revived in the nineteenth century with a new slant.112 Private musings on death by individuals and in the consolation literature had this in common: a good death began at home, in the company of friends and family, and often ended with an elaborate burial ritual.113 By contrast, a bad death occurred in the “wilderness,” away from home, alone or surrounded by strangers.114 In these terms, it was thus almost impossible for the people who went down with the Lexington to experience a good death. Uneasiness about this subject no doubt plagued many of the loved ones of the victims, as well as general audiences receiving news of the disaster—and may have prompted what seems like an excessive rumination on rotting corpses in A Warning Voice from a Watery Grave!

Alternatively, prints like the Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound posited another solution to this disquieted audience—one that encouraged forgetting. In its dramatic yet ultimately delicate handling of a mass fatality, the work helped to move the viewer rhetorically through a sequence of possible responses, from excitement to wretchedness to the hope of redemption. Moreover, an important part of its appeal may rest in its condition as a picture—its ability to preserve a moment in time—tempering the text, which presents the narrative through a longer course, one that inevitably results in death and despair. In defiance of actual history, prints such as the Dreadful Wreck of the Mexico and the Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound show a quantity of living victims, as if in some alternate history they will be rescued. In essence, these prints keep them alive in perpetuity.

Navigating Formidable Shoals

Nathaniel Currier launched a business in uncertain times. The formative years of Currier’s enterprise were bracketed by events that included a massive fire, an economic depression, and several large-scale technological catastrophes. These calamities transpired within a nation that was changing at a rapid rate, circumstances that unsettled many Americans and caused lingering insecurities. These same Americans evinced a stubborn faith in progress and oft-professed determination to overcome adversity. As the market for advice manuals suggests, middle-class Americans were struggling to find their place in the world, if only some safe middle ground out of harm’s way. In the face of uncertain fate, they sought out ways to reconcile what was going on around them, including imagery that could give voice to their fears, ideals, and even secret pleasures. Currier and his associates gave them just such catharsis—representations that created this imaginative space. Indeed, the resounding success of Currier’s later firm in partnership with James Ives illustrated his keen intuition about the needs and desires of his audience. In the drama and complexity of the early disaster images that helped set his career in motion, we see some of the mechanisms that lit the way to such audience sensitivity, from which he learned lessons that propelled him to fame. To us, these images offer a privileged point of entry into issues of nineteenth-century viewership. Rich repositories of emotion and ideology, they demonstrate the remarkable human capacity to hold, at once, complex and contradictory ideas and the equally remarkable way makers of culture navigate these formidable shoals.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1518

PDF: By Which Melancholy Occurrence: The Disaster Prints of Nathaniel Currier, 1835–1840

Notes

- In 1852 James Merritt Ives joined Currier’s business as a bookkeeper; by 1857, Ives became a full partner in the business, which was active until 1907. ↵

- At the height of the firm’s success, Currier and Ives were responsible for as much as 95 percent of the images in circulation, as noted in Bryan F. Le Beau, Currier and Ives: America Imagined (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001), 1. ↵

- The terms catastrophe and calamity also appear in the newspapers with great frequency. ↵

- Kevin Rozario notes the persistence of this premodern use of the term even into the contemporary era. See Kevin Rozario, The Culture of Calamity: Disaster and the Making of Modern America (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2007), 11. Period literature suggests that the antebellum audiences of Nathaniel Currier’s prints largely clung to the divine origins of disaster. ↵

- Currier images that prescribed proper behavior could range from the overt—such as thirty prints on the consequences of intemperance (the first of which was published in 1841)—to more subtle messages “showing women in their ‘proper sphere’ and enjoying it.” Le Beau, Currier and Ives, 181. ↵

- David Tatham, John Henry Bufford: American Lithographer (Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, 1976), 50, 51. According to Tatham, “Apprentices in the next decade would find themselves more narrowly trained.” ↵

- As recounted by Le Beau, Currier would receive a draft illustration from one artist—perhaps showing only a background—and he would send it along to another in-house artist with instructions to add whatever figures Currier had in mind. See Le Beau, Currier and Ives, 22. ↵

- Tatham, John Henry Bufford, 51–52. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- See Harry T. Peters, Currier and Ives: Printmakers to the American People (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., Inc., 1942), 5. The correct title of the building is “Merchants’ Exchange.” The singular possessive, “Merchant’s,” appears in the title of Currier’s print. ↵

- Le Beau, Currier and Ives, 19. ↵

- Russell Crouse, Mr. Currier and Mr. Ives: A Note on Their Lives and Times (Garden City, NY: Garden City Publishing, 1936), 4–5. The print was copyrighted in 1835, affirming the speed with which it was produced. See Warren A. Weaver, Lithographs of N. Currier and Currier and Ives (New York: Holport Publishing Company, 1925), 25. It is quite possible that Currier and Bufford’s first attempt at a disaster print was the undated Ruins of the Planters Hotel, Which Fell at 2 O’Clock, on the Morning of the 15th of May 1835 Burying 50 Persons, 40 of Which Escaped with Their Lives. The relative rareness of this print suggests that this first experiment in disaster imagery was not as successful as Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange. ↵

- John D. Stevens, Sensationalism and the New York Press (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 12. ↵

- A comparable death toll today would amount to more than one hundred thousand. See John Noble Wilford, “How Epidemics Shape the Modern Metropolis,” New York Times, April 15, 2008. ↵

- Robert G. Albion, The Rise of the New York Port (New York: Scribner, 1939), 235–36, as cited in Stevens, Sensationalism, 10–11. ↵

- “The Conflagration,” Herald, December 18, 1835. ↵

- “Awful Desolation of New York by Fire,” Extra Sun, December 19, 1835. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Dreadful Calamity,” New-York Spectator, December 21, 1835, in 19th Century U.S. Newspapers, electronic resource (accessed January 2, 2015). ↵

- It should be noted that audience responses to such prints as the Ruins of the Merchant’s Exchange, however, can only be indirectly gleaned. The distribution for lithographic prints often involved street peddlers, and provenance of the large numbers of these moderately priced prints is impossible to trace. Nor did viewers record their impressions of the print in formal ways. Evidence such as advertisements from the makers do not shed light on audience, as Currier and Bufford, if they advertised at all in the period between 1835 and the early 1840s, seem not to have advertised single prints but the variety of prints they proffered (for an example of Currier’s advertising strategy see the Weekly Herald, April 16, 1842; for an example of Bufford’s advertising see the Herald, August 8, 1836). ↵

- Versions of this slogan appear in several places, most notably as the title of the catalogues the firm sent to agents who sold its output. A letter to these agents references the “Catalogue of Popular Cheap Prints,” quoted in Peters, Currier and Ives, 11–12. ↵

- Wages decline about 15 percent after the Panic of 1837; see Stanley Lebergott, “Wage Trends 1800–1900,” in Trends in the American Economy in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1960), 462, 464. In 1842, when wages had not changed significantly, Charles Dickens notes a profusion of prints as decorations in the homes of the residents of the impoverished Five Points area of New York. See Charles Dickens, American Notes (New York: The Modern Library, 1996), 117. ↵

- According to Karen Halttunen, these manuals surfaced in response to fears that mass rural-to-urban migration of young people would facilitate the breakdown of the social order and threaten the republican experiment. The popularity of these manuals is evidenced by the number of titles and iterations they enjoyed in this period. Published in 1833, Young Man’s Guide by William A. Alcott, for instance, was reissued in twenty-one editions by 1858. See Karen Halttunen, Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830–1870 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1982), 1–32, 95. ↵

- Halttunen, Confidence Men and Painted Women, 93. ↵

- “The Conflagration,” Herald, December 18, 1835. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Lowell M. Limpus, History of the New York Fire Department (New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, Inc., 1940), 145, 164–65. ↵

- Le Beau, Currier and Ives, 302. ↵

- For a detailed analysis of the hagiographic treatment of firemen in Currier’s prints and particularly of The American Fireman, see Amy S. Greenberg, Cause for Alarm: The Volunteer Fire Department in the Nineteenth-Century City (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), 20–21. ↵

- The image of bundles of goods bobbing away from a disaster, as well as the themes of desperation, loss, redemption, and potential salvation, will resurface in the Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound print, which also betrays a complicated relationship between commodities and the people who consume them. ↵