Closer to Mainstream: Dorothy Liebes Goes Digital

PDF: Sato, Closer to Mainstream

Review of the digital exhibition for A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes

Curated by: Susan Brown and Alexa Griffith Winton, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

In-person exhibition schedule: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, July 7, 2023–February 4, 2024

Online exhibition: https://exhibitions.cooperhewitt.org/dorothy-liebes/

Exhibition catalogue: Susan Brown and Alexa Griffith Winton, eds., A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes, ex. cat. New York: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, in association with Yale University Press, 2023. 253 pp; 175 color illus.; 18 b/w illus. Hardcover $50.00 (9780300266153)

One artifact that encapsulates the place of textile designer Dorothy Liebes (1897–1972) in the postwar cultural landscape is an admiring profile in Life magazine from November 1947. Photographed at the loom in her San Francisco studio, storage bins spilling over with yarn behind her, Liebes was lauded as a prescient tastemaker for the vibrant, mixed-media samples she had designed for various US textile firms.1 Like Jackson Pollock’s storied spread in the same magazine two years later, Liebes’s anointment as “top weaver” evidences a crossover into the mainstream, one that might firmly establish her name within popular culture. This was not to be, however; following Liebes’s 1970 solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York and her death two years later, this lion of midcentury design would fade into obscurity, despite her transformative influence on the development of modern textiles in the United States and elsewhere.2 Starting in the 1940s, the “Liebes look” would come to signal exuberant colors and exaggerated textures, characteristics foregrounded by Liebes’s insistence on clearly articulated weave structures and accented by her embrace of Lurex, a synthetic metallic yarn (fig. 1). These distinctive formal concerns would be absorbed into the zeitgeist throughout the postwar period, in large part through Liebes’s work for industry, even as the designer herself was mostly forgotten.3

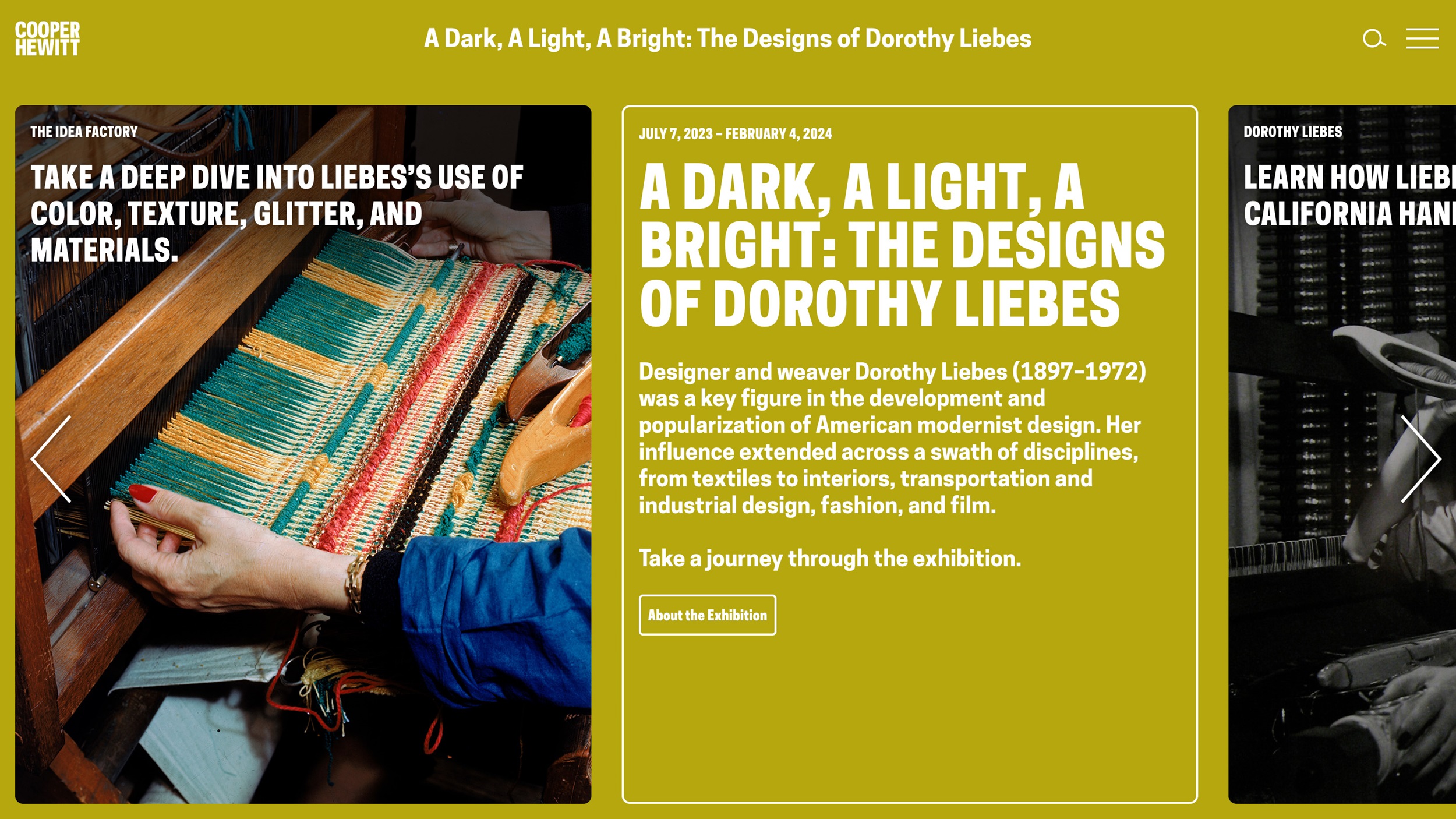

The landmark 1970 Liebes survey appears to be the point on which Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, trained its sights with the recent exhibition A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes. Curated by Susan Brown and Alexa Griffith Winton, this first retrospective treatment of the designer in over five decades reasserted Liebes’s influence on midcentury textiles for new viewers, including viewers who were unable to visit the museum in person. Although the physical exhibition closed in February 2024, an accompanying digital component remains online (fig. 2). Rather than trying to replicate visual or experiential aspects of the in-person exhibition, the digital exhibition (as the museum is billing it) aims to educate its viewers on Liebes’s multidimensional career with an impressive collection of content—forty-nine short essays, “object groups” illustrating signature elements of the Liebes look, a few introductory videos and podcasts, and a photographic timeline. Beyond its stated intent of encouraging future scholarship, Cooper Hewitt commits to something more fundamental with the digital presentation: accessibility.4 If Liebes played a democratizing role in midcentury design, as A Dark, A Light, A Bright posits, by mediating between high modern design and evolving consumer tastes, this wealth of approachable content on significant facets of the designer’s practice carries on that legacy.5

The digital content is broken into sections to explore these facets, which include Liebes’s interior design collaborations with architects and decorators, her samples and color consulting for manufacturing, her luxury fabrics for fashion, and her mentorship of other designers and weavers. The sections roughly correspond to the topics of longer essays in the striking exhibition catalogue, a third component of A Dark, A Light, A Bright. Although there is some overlap between catalogue and digital exhibition, with passages drawn from the catalogue texts and reworked for the website, the digital materials include new information and speak to a broader audience than the book.6 Taken together, the in-person exhibition, digital exhibition, and catalogue cover Liebes’s decades-spanning practice to an unprecedented degree and further affirm the museum’s objective of expanding scholarship at multiple levels. As cocurator Winton notes in the catalogue’s introduction, the 2021 digitization of Liebes’s papers at the Archives of American Art boosted the development of the Cooper Hewitt exhibition.7 While Liebes’s papers are online and available to anyone in their entirety, the digital component of A Dark, A Light, A Bright is a welcoming starting point before delving into the archives.

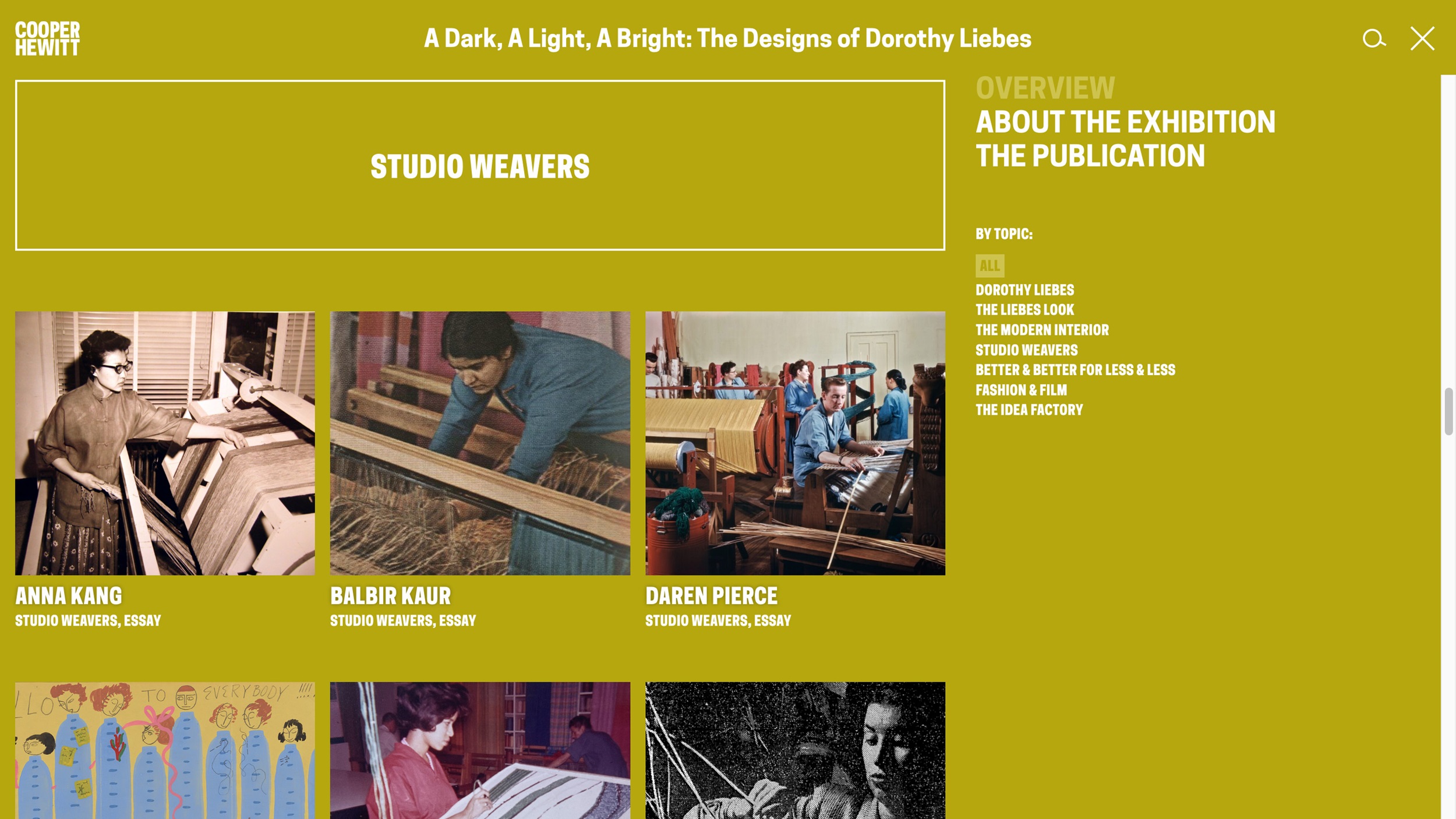

One particularly absorbing section of the digital exhibition looks at weavers and designers who worked as part of Liebes’s studios in San Francisco and later in New York (fig. 3). Drawing on archival documents, period sources, and new interviews, the short essays on painter Emma Amos, interior designer Daren Peirce, knitter Mary Walker Phillips, and eleven others reveal a supportive studio atmosphere that encouraged individual growth as much as collective output. For a number of these artists, the Liebes studio was one stop along their cross-disciplinary paths; yet the skills they developed there, and the networks they gained entry to, seemed to stay intact even after they had moved on. While another section provides an overview of Liebes’s career, on the whole A Dark, A Light, A Bright does not go out of its way to biographize the artist—which, for a woman subject working in a craft medium, is unusual and refreshing. Still, indications of Liebes’s character, such as her drive, inventiveness, generosity, and sociability, come through in these accounts of how she affected, and was affected by, the people she welcomed into her studio.8 It is one thing to argue for Liebes’s influence on postwar design through analyses of the work, but also mapping out the specifics of her impact on individual colleagues, as this section does, results in a richer, more compelling case for it.

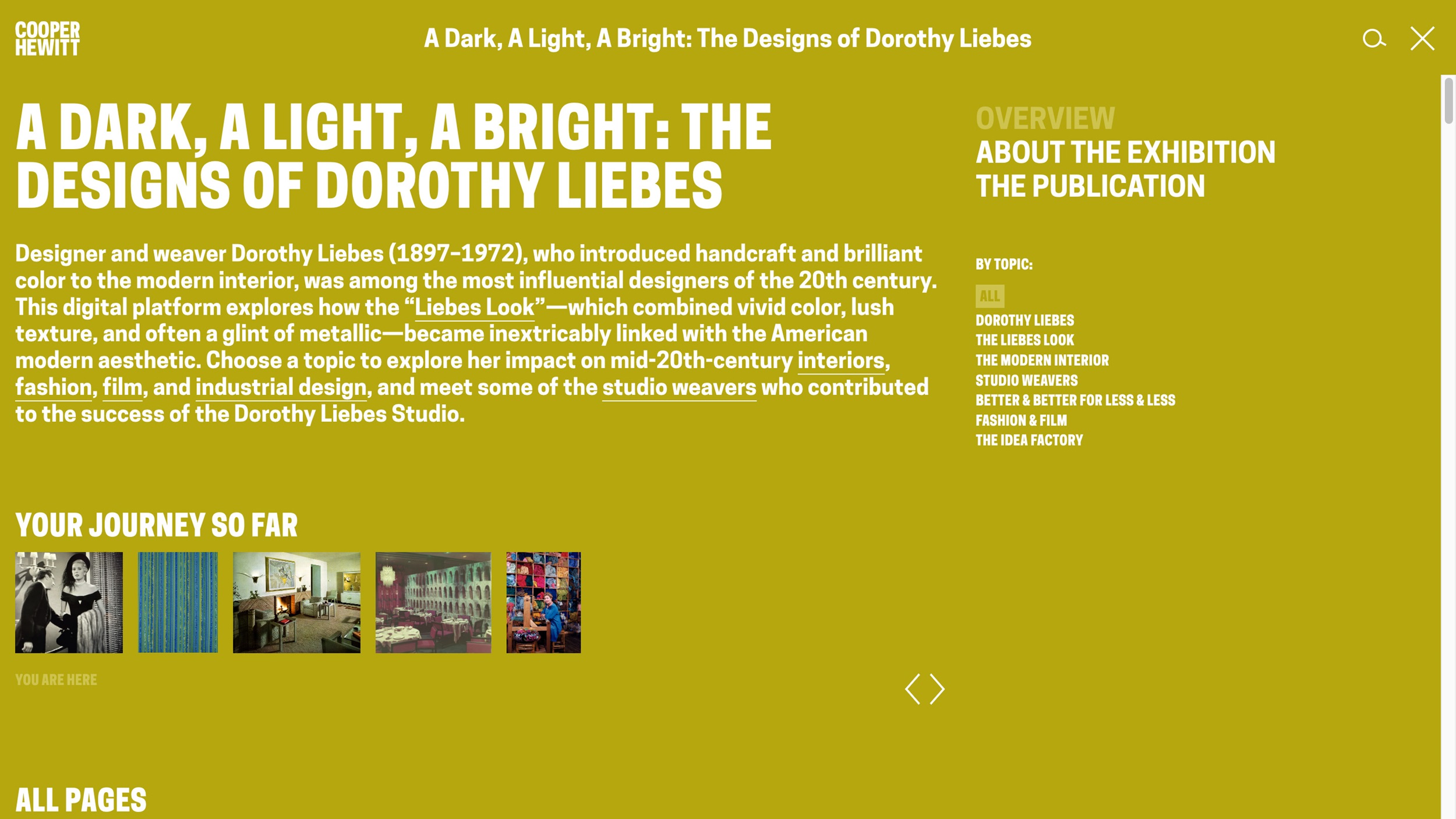

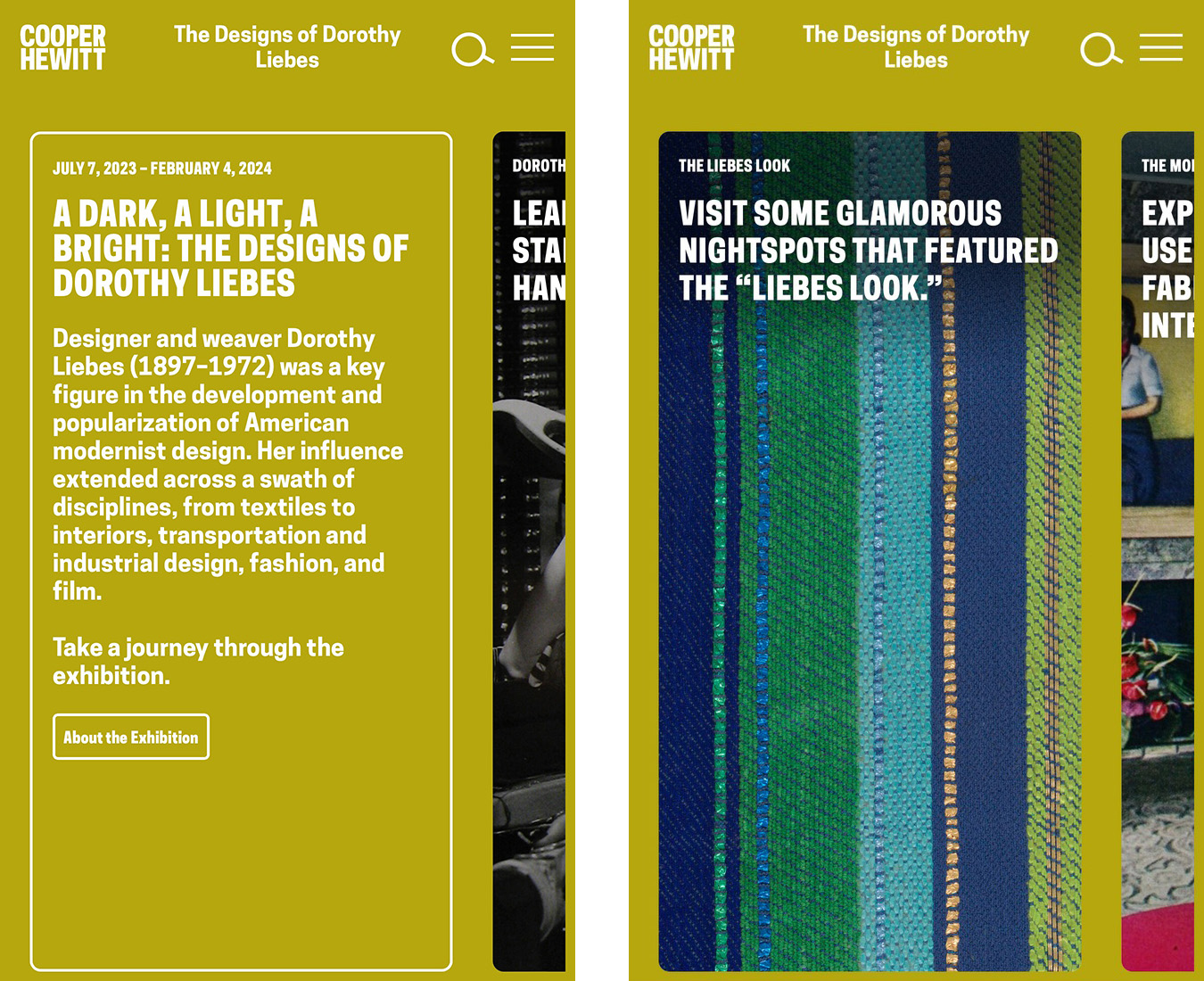

The digital exhibition’s design is sleek and graphic, if at times fiddly to navigate, depending on the device a viewer is using. Its main page (see fig. 2) encourages a nonlinear progression through the many subpages: viewers can scroll horizontally and select from among the seven content areas, which are presented without defined hierarchy; once a content area has been selected, the “Next Show Me” feature then limits viewers to a choice between two subpages, with the idea that one would continue choosing and viewing subpages within that content area until all have been exhausted. Viewers could then return to the main page to start the process over with another content area. Alternatively, viewers can also click the menu icon at the top right to access the “Overview” page, an overlay that slides up from the bottom of the screen to conceal the main page (fig. 4). The full range of the exhibition’s content is viewable only on this Overview page, which requires scrolling vertically at length to see thumbnails for the various subpages, organized by content area. As a result, toggling between the main page and the Overview page on a laptop can be disorienting; while the overlay is structurally dependent on the main page, it directly links to much more content, and indeed it could function as the exhibition’s main page on its own.

Unexpectedly, the digital exhibition might be better experienced on a smartphone. The bold design elements of the main page are more potent, yet still readable, in this smaller, vertically inclined format (fig. 5), and the interface of the content-heavy Overview page is more streamlined.9 The smartphone viewing experience also obscures the exhibition’s lack of zoom-in capabilities—its short essays are liberally illustrated with small-scale archival and period images, but these cannot be enlarged or magnified. On a laptop (or desktop), the lack can leave one feeling thwarted, especially given Liebes’s emphasis on texture and then-radical materials.10 On a smartphone, however, the images fit the width of the screen, subduing the impulse to zoom in. Overall, this thoughtfulness toward the smartphone viewer returns us again to the implicit goal of accessibility, as a general audience is more likely to encounter the digital exhibition on a phone. It is an understanding that seems to have shaped Cooper Hewitt’s attitude toward digital exhibitions across the board; notably, the design of A Dark, A Light, A Bright is identical to that of three other digital exhibitions currently on the museum’s site.11 The efficiency of a platform approach surely enables the museum to offer more content to a wider viewership, though it does not allow the design as much flexibility to respond to individual subjects, either functionally or visually.

In terms of the content, there are a few topics the Liebes digital exhibition leaves surprisingly unbroached. For example, it does not address gender politics at any length (nor does the catalogue, for that matter). This might be related to the apparent disinclination to focus on Liebes’s life story. While viewers can still make extrapolations about gender dynamics from the telling biographical details that do surface in the essays, the larger omission means that some important conversations are not initiated. Delving into gender politics would bring more scrutiny to Liebes’s exclusion from postwar design histories and the degree to which this was affected by the intersection of her profession and her gender—for the two are linked inextricably in this context.12 It is true that similar discussions are already central to the scholarship on twentieth-century textiles, so there might be value in temporarily setting them aside here, in view of the target audience.13 With each of its components, A Dark, A Light, A Bright takes as a given Liebes’s merit as a subject for examination, without any need to categorize or justify. The nature of Cooper Hewitt as an encyclopedic museum of design facilitates this, but perhaps the project also signals a change in how textiles are being approached now, at least for broader audiences.

A Dark, A Light, A Bright contributes to an emerging understanding that the postwar period in the United States was incredibly fruitful for textiles. As exemplified by Liebes, utilitarian textiles were being produced in innovative ways, with unorthodox materials, and for novel applications, against the backdrop of a booming economy and widespread societal changes.14 There was also a modern tapestry revival, imported from France and evident in the robust US market for tapestry and institutional interest in the medium for decades following the end of the war.15 By the end of the 1950s, fiber artists would begin experimenting with nonutilitarian textiles as well, moving quickly over the next decade from woven wall hangings that resembled practical textiles to free-hanging or freestanding objects that very much did not. Liebes would not champion fiber art as it emerged, deriding much of it as “dust catchers.”16 Yet her aestheticization of utilitarian textiles, her elevation of their formal qualities, cannot entirely be separated from these other artistic developments in nonutilitarian textiles.17 Neither can Liebes’s overall practice remain absent from histories of postwar design, nor postwar history at large, as Cooper Hewitt’s digital exhibition makes plain.

Cite this article: Analisa Coats Sato, “Closer to Mainstream: Dorothy Liebes Goes Digital,” review of A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 2 (Fall 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19262.

Notes

- The article’s copy proclaims Liebes “far and away the best and most successful textile designer in the U.S. and probably the world.” “Top Weaver: Dorothy Liebes Uses Metal, Plastic, Wood,” Life, November 24, 1947, 93. Liebes’s Life profile is briefly mentioned at the beginning of an introductory video made by Cooper Hewitt. See “Get to Know Dorothy Liebes,” A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2023, https://exhibitions.cooperhewitt.org/dorothy-liebes/485-2. ↵

- Design historian Emily M. Orr writes about Liebes’s cultivation of a global network of designers and manufacturers through her travels outside the United States, in “Modern Weaving’s Global Ambassador,” in A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes, ed. Susan Brown and Alexa Griffith Winton (New York: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, in association with Yale University Press, 2023), 122–34. ↵

- In historian Regina Lee Blaszczyk’s estimation of Liebes’s designs for DuPont, “Without a doubt, Liebes had an impact on mass market taste with her ‘vibrating colours’ and unusual textures. . . . She created textiles that balanced the familiarity of handicraft with Modern design, landing somewhere in the great middle ground,” in “Designing Synthetics, Promoting Brands: Dorothy Liebes, DuPont Fibres and Post-war American Interiors,” Journal of Design History 21, no. 1 (Spring 2008), 88–89, https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epm038. See also Monica Penick, “The Liebes Look: Better and Better for Less and Less,” in Brown and Winton, A Dark, A Light, A Bright, 170–84. ↵

- This objective of spurring future scholarship is confirmed by cocurator Winton in the exhibition catalogue (9). I acknowledge that “accessibility” can have multiple applications here; while the content of the digital exhibition is accessible in terms of its targeting a wide audience, its technological accessibility is somewhat less so. A quick scan of the main page using accessbilitychecker.org, a popular web-based tool, indicates an issue with the contrast ratio between the white text and green background, for example. ↵

- In the foreword to the catalogue, Cooper Hewitt director Maria Nicanor emphasizes Liebes’s role as mediator between modern architects, designers, and the public and credits her with democratizing midcentury design (4). ↵

- Much of the overlap comes from texts written by curators Winton and Susan Brown, while the content that is exclusive to the digital exhibition was chiefly contributed by other Cooper Hewitt staff. ↵

- Winton, introduction to Brown and Winton, A Dark, A Light, A Bright, 7. Dorothy Liebes papers, ca. 1850–1973, bulk 1922–70, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/dorothy-liebes-papers-9143. ↵

- Textiles scholar Erica Warren considers Liebes’s mentorship and community building in greater depth in “Fission: Design and Mentorship in the Dorothy Liebes Studio,” in Brown and Winton, A Dark, A Light, A Bright, 186–200. ↵

- Specifically, the thumbnails for each content area on the Overview page now appear in rows of two, rather than three, and what was a sticky menu on the right side of the page (on the laptop) is now confined to the top of the page (on the smartphone). ↵

- Such materials included cellophane, vinylite, wood, polystyrene, and Lurex, among others. A summary of Liebes’s uses of materials features in both the digital exhibition and the catalogue. See Susan Brown, “Materials,” Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes, https://exhibitions.cooperhewitt.org/dorothy-liebes/materials. ↵

- At the time of this writing, these digital exhibitions are An Atlas of Es Devlin, Designing Peace, and Willi Smith: Street Couture. ↵

- Winton briefly acknowledges the “reflexive prejudices” of design scholarship, which has often underestimated the contributions of both women and textile designers. She also suggests that black-and-white photographs of Liebes’s textiles are partly to blame, because they diminished Liebes’s “remarkable gifts as a colorist”; in introduction to Brown and Winton, A Dark, A Light, A Bright, 9. ↵

- Significant studies of twentieth-century textiles and gender include Elissa Auther, String, Felt, Thread (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009); T’ai Smith, Bauhaus Weaving Workshop: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014); and Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art + Textile Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017). ↵

- Virginia Gardner Troy lays out the interrelated developments in US textiles and society in the postwar period in “Textiles as the Face of Modernity: Artistry and Industry in Mid-Century America,” Textile History 50, no. 1 (May 2019), 23–40, https://doi.org/10.1080/00404969.2019.1587237. ↵

- For a thorough unpacking of the postwar modern tapestry revival in France and the United States, see K. L. H. Wells, Weaving Modernism: Postwar Tapestry Between Paris and New York (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019). ↵

- As Liebes wrote to her friend Elizabeth Bayley Willis in 1966, “Here we have these knitted, poorly constructed, poorly engineered things called Wall Hangings. Actually, they are dust catchers and I am unsympathetic with most of it”; quoted in Troy, “Textiles as the Face of Modernity,” 36. ↵

- Textiles scholar Sarah V. Mills has situated Liebes’s practice as part of a wider “beautification of utilitarian textiles” that began in the United States in the late 1930s. See her “Weaving Modern Forms: Fiber Design in the United States, 1939–1959” (PhD diss., City University of New York, 2019), 132. ↵

About the Author(s): Analisa Coats Sato is a PhD candidate in Art History at CUNY Graduate Center.