Maryland Institute Black Archives: A Post-Custodial Project

PDF: Tani, Maryland Institute Black Archives

In his 2018 book How Art Can Be Thought: A Handbook for Change, artist Allan DeSouza questions the promotion of individuality over collectivity in art education:

This ideology (and it is ideology) fails to recognize or value the collective labor and knowledge already expended to produce any given individual and which forms the history behind what that individual produces (I include unpaid as well as paid labor—parents, teachers, informal advisors, friends and lovers, colleagues, peers, previous employers, the multitude who clean up after, etc.). In this regard, every artist and artwork has a collective lineage.1

Giving shape to collectivity while acknowledging artists’ individual stories is a primary goal of the Maryland Institute Black Archives (MIBA), a born-digital archive focused on the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in Baltimore (fig. 1). Developed by a recent alumnus, Deyane Moses (BA ’19, MFA ’21), it is also a form of institutional critique that takes aim at the storied art school’s advancement of racist, and specifically anti-Black, policies and attitudes across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. An ethos of postcustodialism, which recognizes the harm that archives can do, shapes MIBA’s anarchival sensibility and local focus. This emphasis sets it apart from other born-digital archives (and passion projects) that document African American art practices more comprehensively—say, the African American Performance Art Archive or Kimberly Drew’s Black Contemporary Art blog—or from wide-ranging and thematic digital humanities projects funded by major grants, like Renée Ater’s Contemporary Monuments to the Slave Past.2 Rather than represent artworks or objects, MIBA documents the history of MICA’s Black community with a clear-eyed understanding of institutional racism and how it functions in the past and present across more than a thousand primary and secondary artifacts, including photographs, rare books, art, documents, music, clippings, and oral histories.3 As DeSouza argues above, within an educational setting the slippage between institutional and instructional racism can be unnoticeably swift. Thus, as an activist archive, MIBA offers a reparative instruction to the online visitor in its approach to the collective history of how art is taught and to whom, challenging conventional research strategies in American art history from many angles.

The project originated as an exhibition titled Blackives: A Celebration of Black History at MICA (January 28–February 22, 2019), held at the Pinkard Student Space Gallery at MICA. Curated by Moses, who was then finishing her BA in photography, it combined the ideas of “Black lives” and “archives” to honor histories of Black people associated with MICA and to highlight the institution’s racist history. It could have ended as a timely project for Black History month, but the exhibition’s vitality opened a fertile seam in the institutional structure within which public interest in the project’s other stories has only grown. The physical exhibition became a digital repository of photographs, archives, and oral histories that lives at https://www.miba.online. Primarily digital, its online format conceals the offline activities of MIBA as a collaborative community archive, whose mission is to “correct the history of MICA from the 1800s to the present” and to “preserve Black history at MICA and empower our community” with a special emphasis on Black Baltimoreans.4 Scrappy and nimble by both default and design, the project presents some challenges of use, but its resiliency lies in its parainstitutional arrangement (it exists independently from MICA) and its commitment to the practice of postcustodialism.

As an undergraduate photography major, Moses began photographing and interviewing students and other members of the campus community. An encounter with photographer Dawoud Bey in the spring of her junior year, she recalls, inspired her to look to her community.5 Curious about the history of Black students at MICA, she researched the institution’s archives in the Decker Library Special Collections. Starting with five names, she chronicled students who had tried to come to MICA when it was still a segregated institution (1895–1954). In its parameters, the project was and is an analysis of how anti-Black racism becomes institutionalized.

The Archive, the Institution, and Postcustodialism

MICA, one of the oldest art schools in the country, was founded in 1826 in Baltimore as the Maryland Institute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts. The slippage between MICA and MIBA, in substituting “Black archives” for “college of art,” announces an alternative history of Black life within the institution—but also outside of it. For Moses, the archive is a key infrastructure of Black life, a way of housing knowledge and preserving history without centering the physical accessioning of property. MIBA documents the college’s first Black artists, but it also speculates on the potential of aspiring Black students who were denied admission based on their race. It includes photographic portraits and oral histories from MICA’s Black community (including staff members who work in custodial, security, and other “service” capacities for the institution), from 2019 to the present.

While Moses rents a small storage unit to house documentary images, facsimiles, and ephemera that have been given to the archive, MIBA is modeled on a postcustodial approach to archives that centers born-digital content. Postcustodial archival practice, according to the Society of American Archivists, is a systematic approach to preservation in which archivists may no longer physically acquire and maintain records but instead provide management and oversight for records that remain in the possession of their creators, often through digital repositories.6 For MIBA, this means yielding authority to its community: “The primary role of the collection is to empower the Black Community and motivate social change within the field of art and design. By preserving, celebrating, and providing equal access to ignored and untold stories, we reclaim our power to construct our own narratives and determine what has value for the present—and the future.”7 Within the broader context of art history’s reckonings with methodologies and values rooted in settler colonialism and/or imperialism, we can understand postcustodialism as an archival method that is nonextractive, that privileges trust rather than acquisition, and that values access to knowledge and stories over the preservation of physical objects. In any decision-making platform—whether archival or curatorial—one engages in the process of discrimination, and this ethical tether provides crucial grounding.

MIBA’s parainstitutional position holds radically disruptive potential, but without the infrastructural stability that concrete affiliation might provide, practical and technical challenges arise. In considering MIBA as an archival and curatorial project, I struggled with the structure of the website itself, where it remains unclear if the postcustodial concept or the inchoate nature of the project drives the user experience. Due to limited resources, the website runs on a barebones Squarespace format and lacks accessibility measures (such as transcripts of video content, a search option, and alt-text for images). It strikes this reader as a constraint on Moses’s curatorial vision that makes the project’s postcustodial values challenging to prioritize.

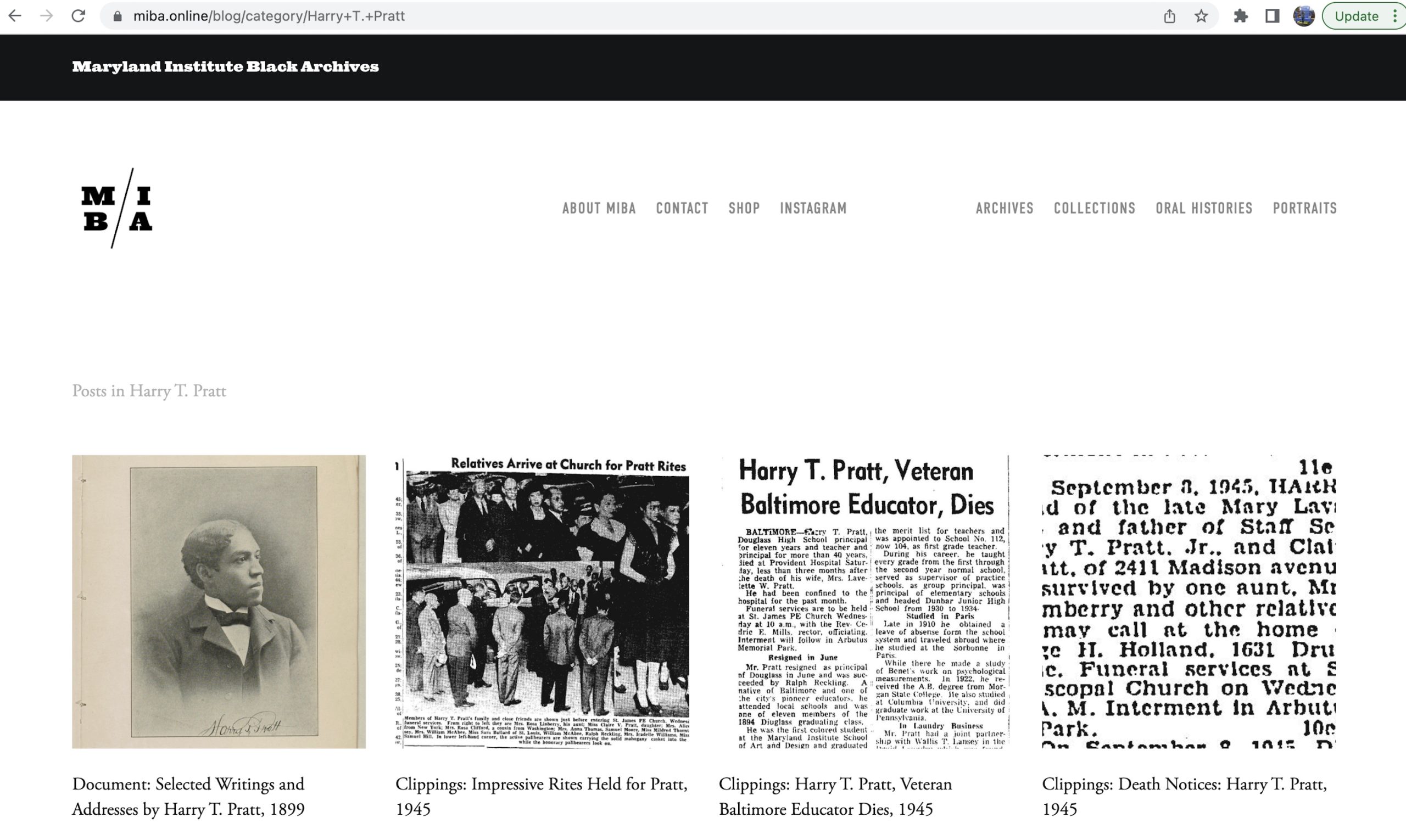

Take, for example, one of the site’s most prominent subjects, Harry T. Pratt. MICA admitted Pratt as its first African-American student “by legal appointment” in 1891.8 His enrollment and that of the few Black students who followed caused more than one hundred white students to withdraw in protest by 1895; the financial duress of tuition loss led the Maryland Institute board to protest as well, and after Pratt’s graduation in 1895, they established an admissions policy restricted to “reputable white pupils.”9 The tag “Harry T. Pratt” reveals the most robust archival constellation on MIBA, with seventeen records, including photographs, Pratt’s writings, news clippings, census records, his obituary, and even his ancestry.com profile (fig. 2). While clicking on this category in the “Collections” drop-down menu reveals all associated records, an introduction of Pratt himself does not appear in a central place; it must be parsed from the content of each associated record. One might think that such a central figure for this project would receive structural emphasis.

Troubling the Institutional Paradigm

When I brought up other missing or confusing contextual information in conversation with Moses, given her role as director and curator of the project, she expressed hope that MIBA could receive financial support to hire more staff to improve such framing and add links to external resources, while adhering to the ethical standards of citation. In many cases, however, the content speaks for itself if one reads between the lines—as researchers are trained to do—and the patchy surface of what links the entries to our world is an alluring space for generating more questions that can foster new connections across categories and tags. Given that some entries do have summative introductions (see each entry on Thomas Wiggins), this inconsistency reflects the archive’s ongoing development rather than a purposeful withdrawal from imposing an authorial narrative.10

On the bottom of any page on MIBA, one will see the phrase “powered by Blackives, LLC,” a company founded by Moses after the project’s inception, whose mission is “to provide historical research, archival services, and knowledge mobilization for Black artists and communities.”11 Blackives, LLC, provides both a funding source to MIBA and a vehicle for its community outreach, a necessary build-out for the project’s independent growth (indeed, much of the work happens offline). The project’s inchoate archival form becomes more of a repository than a finding aid, and it both aggregates and selectively withholds content in a way that holds messy possibility. The oral histories, for example, exist as photographs of the speaker and a transcription of their response. Upon reading them, it is clear the speakers were responding to a central query from Moses—but the query is ours to guess, as is her connection with these individuals. Researchers may find such lacunae unsettling; additional metadata and organizational decisions might improve the archive’s functionality while enhancing its capacity to collect evidence of how institutional racism is encoded in visual culture. Take the reproduced page from the book MICA: Making History, Making Art (published to celebrate the school’s longstanding history as the oldest accredited art school in the country).12 Vaguely titled in MIBA as “Document: Page 91, 2010,” the page is the only evidence of African American students’ history at MICA in that richly illustrated volume, and it, as Moses noted to me, acknowledges exclusion but does little to reveal those students’ stories.13 As MIBA seeks to fill the space between evidence of exclusion and narratives of presence, I would like to see this page bearing a more descriptive name and populated with links to other records in the archive that flesh out the space between its mention of students, their lives and achievements, and the broader community.

On February 21, 2019, Samuel Hoi, the president of MICA, released a campus-wide memo apologizing for the college’s racist admissions policies between 1895 and 1954, while also promoting the institution’s “multi-faceted DEIG [diversity, equity, inclusion, and globalism] plan.”14 The outsized impact of Blackives on the campus community inspired the administration’s invitation to extend the show for another month in a more prominent space: the neoclassical Main Building, which houses the college administration, drawing studios, and twenty-two classical sculptures used for study (fig. 3). There, in the arcaded double-height atrium, Moses installed two walls of exhibition material—both photographs of people and reproductions of archival material—and hung curtains that obscured the sculpture gallery from view. On the front steps of the building, she organized “Take Back The Steps,” a remembrance of Robert H. Clark, the first student who was appointed in 1895 by Harry S. Cummings, the city’s first African American councilman, but denied admission because of his race. He stood defiantly on the front steps of the administration building the following year to demand that the institution follow through on its promise to the city. The hand-painted banner originally held by demonstrators hung vertically in the Main Building’s atrium as a trace of that commemoration. Yet it is still hard to know if the exhibition generated real transformation at an institutional level or if it merely provided positive optics for a school that, since then, has come under fire from its own faculty. In September 2020, senior leadership at the college issued a vote of no-confidence, and the college laid off recently unionized staff members ahead of initial contract negotiations in July 2022.15

That “take back the steps” banner is an apt metaphor for the project itself: held communally, handmade, and shaped by the institution but unmoored from it, it articulates both the project’s possibility and its limitations. One might take back the steps, but can one change what’s inside? MIBA’s achievements are commendable: it shook the foundations of a long-standing institution, energized a community of collaborative stewards, and introduced a radical standard of care into archival practice at MICA. The challenge it faces is how to create an archive—a kind of institution unto itself—without the pitfalls of institutionality. I initially believed this effort meant that the archive had to embrace a precarious existence—and wondered what it meant to entrust preservation of memory and voices to a structure of precarity. But perhaps that reflects my own narrow thinking about institutions: that without them, without their administrative structure and organizational power, things would fall through the cracks. MIBA illustrates how the digital yields potential for a more dynamic and equitable form of both preservation and access. Thus, while the archive will certainly change over time, what remains consistent is the project’s ethical core of postcustodialism: “to support community collectors in maintaining control of their archival records while providing preservation support and public access.”16 Moses’s application of the concept here is motivated by the question of trust. How can one avoid causing harm in archival practice? Some people may have reservations about sharing their oral histories out of fear of retribution; others may be triggered by recounting them. And while some organizations in Baltimore are writing grants for digitizing community archives, does the community trust those entities with their histories?17

As a grassroots archive independent from the college, MIBA survives as a scrappy digital repository with an outsized communal footprint; much of its work involves one-on-one meetings and community workshops, modeling community building as institution building. Depending on available funding, MIBA sometimes has research staff available to add descriptive texts about subjects in the archive. It would be a wonderful teaching tool for students interested in researching African American art history while being mindfully engaged in its present. MIBA is nimble by necessity but also by nature, since the concept of postcustodialism requires a responsive approach to archival care and a platform with flexible infrastructure. Yet as a parainstitutional archive, it exists in a precarious state of contingency. “Our collection is in its infancy and ongoing,” as the website reads, and it will be exciting to witness its growth.18

Cite this article: Ellen Y. Tani, “Maryland Institute Black Archives: A Post-Custodial Project,” review of Maryland Institute Black Archives (digital archive), Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.14589.

Notes

- Allan DeSouza, How Art Can Be Thought: A Handbook for Change (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 41. ↵

- African American Performance Art Archive, https://aapaa.org; Kimberly Drew, Black Contemporary Art (blog), https://blackcontemporaryart.tumblr.com; Contemporary Monuments to the Slave Past, https://www.slaverymonuments.org. ↵

- My capitalization of the term “black” follows the nuanced model of Lisa Uddin and Michael Gillespie, who distinguish Black as a descriptor of a social category from blackness and black as conceptual gestures in “Black One Shot and the Art of Blackness,” liquid blackness 5, no. 2 (2021): 85–93, https://doi.org/10.1215/26923874-9272802. ↵

- MIBA’s emphasis on Black Baltimoreans addresses broader structural frameworks of public policy and access to education: in MICA’s original contract with the city, a Baltimore council member could appoint a student from their district to attend the institute tuition-free. The project’s focus on the history of “Black at MICA” incorporates students (most prominently Henry Pratt, who was appointed by a Black city council member) and also includes the broader Black community of MICA, such as security staff, service workers, etc. For more, see “Community Assessment,” MIBA, 2018, https://www.miba.online/about. My references to MIBA’s website reflect its content upon writing, as of September 2022. ↵

- Deyane Moses, “Document: Take Back The Steps – Deyane Moses’ Speech, 2019,” MIBA, 2018, https://www.miba.online/blog/2018/11/23/photo-harry-t-pratt-yrr4d-fht3g-gx5g7-p75rc-wcs7c-h52nf. ↵

- “Postcustodial,” Society for American Archivists Dictionary of Archives Terminology, accessed October 4, 2022, https://dictionary.archivists.org/entry/postcustodial.html. Moses first learned of the concept through scholars at the University of Texas, likely those affiliated with LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections projects at UT Austin, who have modeled postcustodialism in numerous forms, such as Latin American Digital Initiatives (https://ladi-prod.lib.utexas.edu/en/home), a digital repository for historical materials pertaining to human rights in Latin America. See “Post-Custodial Presentation and Latin America,” University of Texas Libraries Newsletter, no. 21 (2016): 9, https://www.lib.utexas.edu/sites/default/files/utl-nl-fw2016.pdf. Deyane Moses, interview with the author, August 11, 2022. ↵

- “Collections Development Policy,” MIBA, 2018, https://www.miba.online/about. ↵

- Henry Pratt was nominated in 1891 by Harry S. Cummings, the city’s first African American councilman. “Document: Page 91, 2010,” MIBA, 2018, https://www.miba.online/blog/2018/11/23/photo-harry-t-pratt-yrr4d-fht3g-gx5g7-p75rc-wcs7c-bfk8j-watgk-e2wnr-6sbs4. ↵

- This policy held until 1954, when the Brown v. Board of Education decision by the US Supreme Court influenced the board’s unanimous vote to integrate the school. “Document: Page 91, 2010,” MIBA. ↵

- Posts tagged “Thomas Wiggins,” MIBA, 2018, https://www.miba.online/blog/category/Thomas+Wiggins. ↵

- Blackives, https://www.blackives.org/company. ↵

- Douglas L. Frost, MICA: Making History, Making Art (Baltimore: Maryland Institute College of Art, 2010). ↵

- “Document: Page 91, 2010,” MIBA. ↵

- Hoi’s letter continued: “MICA as an institution—represented by its president, vice presidents and board of trustees—apologizes for its historical denial of access to talented students for no other reason than the color of their skin, and for the hardships to those who were admitted but not supported for their success. With a multi-faceted, pan-institutional DEIG plan, we are working to ensure that our campus now and into the future welcomes, respects and supports equally students, faculty, staff, and public members of all backgrounds.” Samuel Hoi, “Acknowledging MICA’s past as we forge together a better future for all,” MICA, February 21, 2019, https://www.mica.edu/mica-dna/leadership/president-samuel-hoi/memo-on-blackives-and-micas-history. ↵

- Valentina Di Liscia, “Faculty Declare ‘No Confidence’ in Senior Leadership at Maryland Institute College of Art,” Hyperallergic, September 14, 2020, https://hyperallergic.com/588170/no-confidence-vote-mica; “Maryland Institute College of Art Set to Lay Off Recently Unionized Workers,” Artforum, July 14, 2022, https://www.artforum.com/news/maryland-institute-college-of-art-set-to-lay-off-recently-unionized-workers-88814. ↵

- Collections Development Policy,” MIBA. ↵

- Deyane Moses, interview with the author. ↵

- Collections Development Policy,” MIBA. ↵

About the Author(s): Ellen Y. Tani is a Smithsonian Institution Postdoctoral Fellow.