Naming Martin Wong

In fall 2022, Stanford Libraries published the Martin Wong Catalogue Raisonné (MWCR) in collaboration with the Martin Wong Foundation and Stanford’s Asian American Art Initiative (AAAI). The project was coedited by Mark Dean Johnson and Gary Ware (Martin Wong Foundation), D. Vanessa Kam (Stanford Libraries, now Emily Carr University), Anneliis Beadnell (P.P.O.W Gallery and archivist to the Martin Wong Foundation), and myself. Catherine Aster from Stanford Libraries served as the project manager, and Gary Geisler and Arcadia Falcone from Stanford Libraries provided technical expertise and support. Doctoral students Paulina Choh, Delaney Chieyen Holton, and Jennie Waldow served as research assistants on the project, and Solomon “Zully” Adler, Doryun Chong, Margo Machida, and Louise Siddons contributed original scholarly essays. Outside of Stanford, our work is indebted to the tireless efforts of Fales Library and Special Collections, especially Nicholas Martin and Marvin Taylor, and to Florence Wong Fie, Martin’s mother and first archivist.

I begin this essay with a list of contributors to underscore the labor, resources, and collaboration required to produce the online Martin Wong Catalogue Raisonné (https://exhibits.stanford.edu/martin-wong). A catalogue raisonné promises a comprehensive account of an artist’s oeuvre. It would seem a monument to artistic genius, the physical manifestation of the myth of the artist as heroic individual. Yet the sheer scope of a single life—especially one as vibrant and multifaceted as Wong’s—necessarily required a team. A life’s work is more than a list of objects; it is an infinite array of connections with others.

The MWCR began in 2018, when the Martin Wong Foundation reached out to Stanford Libraries about a possible collaboration. After several conversations and a Memorandum of Understanding detailing the responsibilities of each party, we began the project in spring 2020. Anneliis Beadnell compiled artwork records, scanned archives, and coordinated new photography. The editorial team met weekly to conduct quality assurance and discuss formatting and content, and they met monthly with the technical team at Stanford Libraries. The entire project took well over ten thousand hours of collective labor to launch. That we were able to publish the project in just over two years was due to the dedication of the team, the relative flexibility of the online format, and the meticulous records of Wong’s work kept by Florence Wong Fie (figs. 1–2).

Many of the questions posed by the editors of this section are addressed by D. Vanessa Kam in the Introduction and Research Guide of the MWCR. Of particular interest is Kam’s discussion of Spotlight at Stanford, an open-source, online exhibition platform developed at Stanford Libraries. Kam’s lucid explanations point to the importance of Stanford Digital Library Systems and Services (DLSS) to the MWCR. We hope that others will consider using Spotlight for their own projects. DLSS’s expertise with digital humanities projects was crucial to every step of the project: workflow, technical questions, and digital preservation. Online resources risk becoming outdated, dysfunctional, or even obsolete over time. Working with DLSS and housing the MWCR within Stanford Libraries solved this problem for us. This assurance about the long-term future of the MWCR is one of the great advantages of collaborating with an academic institution.

The MWCR was the inaugural research project of Stanford’s Asian American Art Initiative, codirected by Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander of the Cantor Arts Center and myself. The MWCR aligns with the AAAI’s core values: accessibility, community engagement, and in-depth art-historical research based on primary source material. The online format allowed us to supplement traditional catalogue raisonné entries with a wealth of primary source information, including Margo Machida’s previously unpublished 1989 oral history with Wong; an in-depth interview with Wong’s best friend, Gary Ware; audio of a 1991 lecture Wong gave at the San Francisco Art Institute; a video portrait of Wong by Charlie Ahearn; and dozens of previously unpublished photographs. Machida also contributed a major essay based on her interview that reveals the depth of Wong’s engagement with transcultural sources.

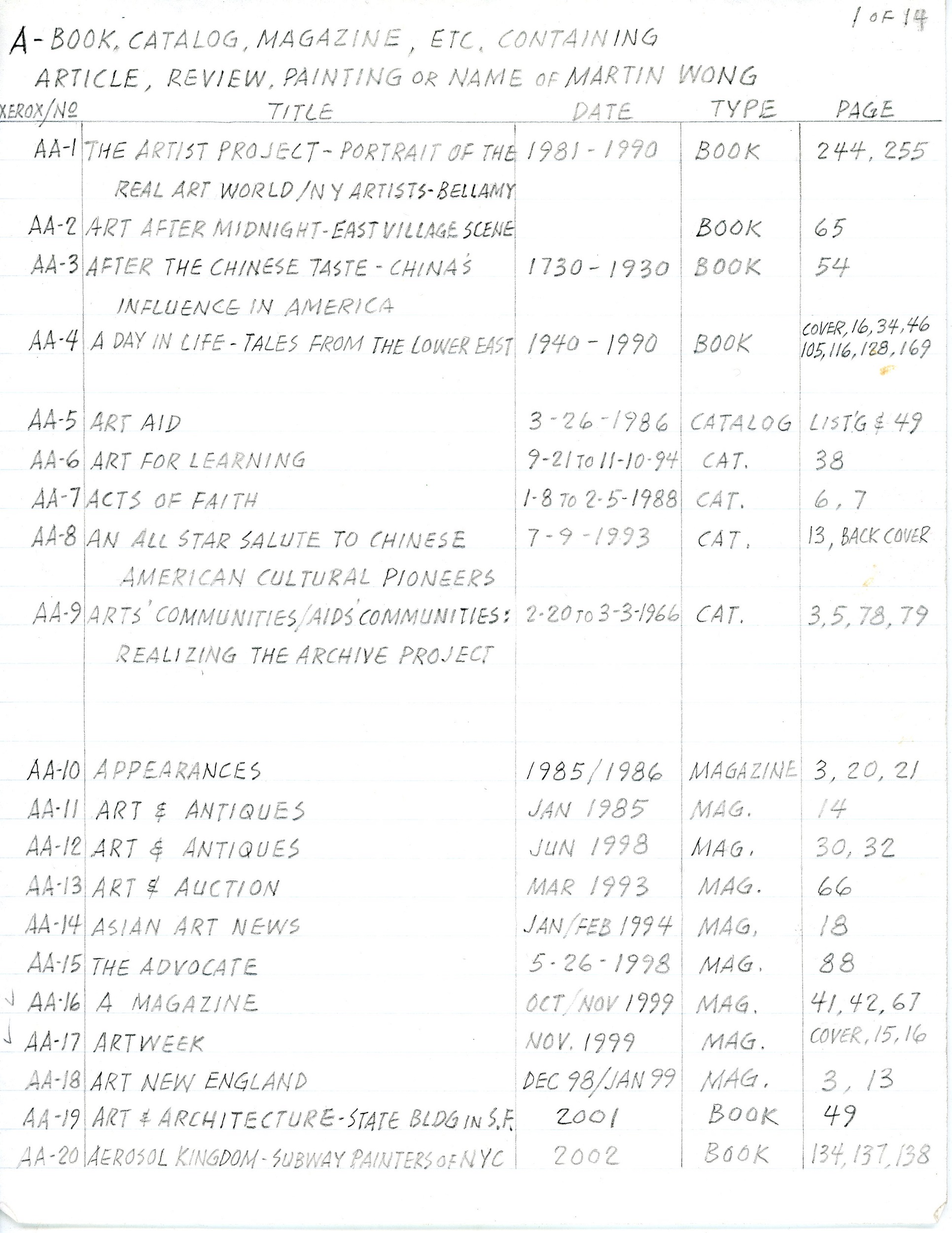

The Spotlight platform allowed us to label entries for works of art with what we called associated topics. These custom metadata topics let us group works together in multiple ways: medium, decade, and exhibition as well as recurring iconography, subjects, and themes (fig. 3). This flexibility is one of the great advantages of a digital format and yielded important insights about Wong’s oeuvre, enabling us to track the transformation of certain motifs and themes throughout his oeuvre. For example, the “poetry” associated topic demonstrates Wong’s engagement with language from his psychedelic-calligraphic scrolls of the 1960s through his use of finger spelling and collaboration with Nyuorican poet Miguel Piñero in New York. Our research also revealed the importance of Wong’s artistic formation in northern California and particularly his involvement with the Angels of Light Free Theater.1 Often elided with the better-known Cockettes, the Angels of Light was a radical queer performance troupe that believed that art should be given away for free (many of the surviving members were delighted that access to Wong’s catalogue raisonné would be free).

Classification posed one of the biggest challenges for the editorial team. Do constellations count as language? Is an eight ball also an eyeball? When a painting includes buildings from Chinatowns in San Francisco and New York, should we label it with “San Francisco Chinatown,” “New York Chinatown,” both, or simply “Chinatowns”? What is the difference between American Sign Language and finger spelling? Names and categories are not mere minutiae but consequential interpretive decisions. As Érich Michaud has shown, art history’s divisions of national and period styles—the consolidation and alignment of an aesthetic with a “people”—shored up the violent ideology of racial homogeneity and European continuity.2 As Sharon Mizota observes, “Metadata isn’t neutral.”3

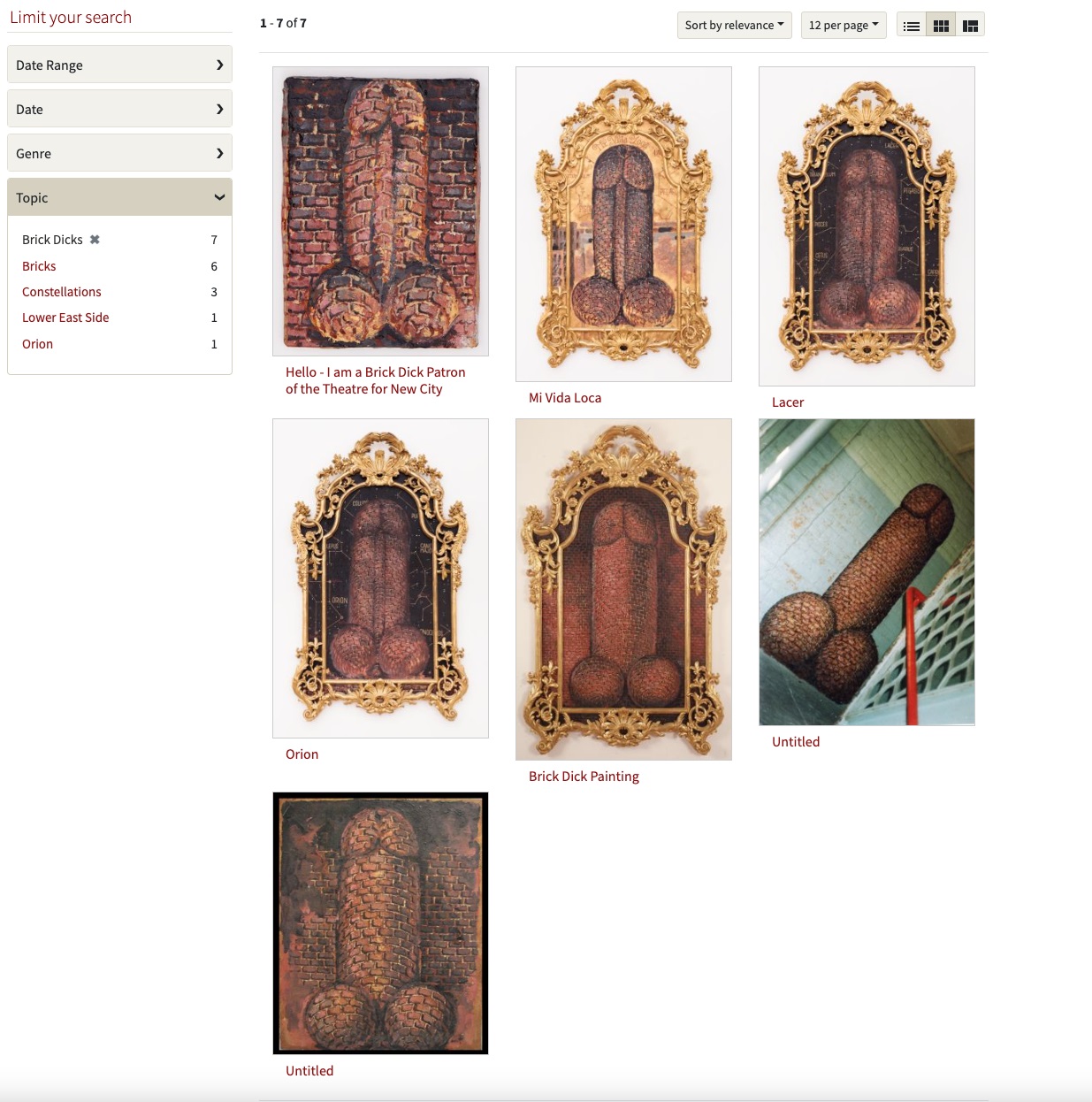

A digital art history project foregrounds problems of classification. Information is organized within templates, and fields are often populated with preset drop-down options. Breadth can bury; naming allows one to search and sort through massive quantities of information. As scholars of Asian American studies have long recognized, naming allows for recognition and visibility, but it also abets classification. Our team felt the challenge of trying to shape Wong’s unruly, expansive oeuvre into the orderly geometry of digital data. Our editorial meetings often involved discussions of the stakes of naming something, of describing it one way or linking it to another. Often, we solved the problem through proliferation, adding numerous associated topics to each entry. We also tried to capture Wong’s own description of his distinctive iconography, for example adding “Brick Dicks” and “Brick Discs” to the long list of associated topics (fig. 4). Wong’s work showed us that one thing could be many things. Behind each term and grouping are hours of discussion, negotiation, questioning, and disagreement. Ultimately, we had trust that the depth of Wong’s practice and each of the individual work will always exceed whatever category we place it in or name we affix to it.

Cite this article: Marci Kwon, “Naming Martin Wong,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17334.

Notes

- See Marci Kwon, “Glittering Visions: Martin Wong and the Queer Counterculture,” Martin Wong: Malicious Mischief, ed. Krist Gruijthuijsen and Agustín Pérez Rubio (Cologne: Walther König, 2023). ↵

- Érich Michaud, The Barbarian Invasions: A Genealogy of the History of Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019). ↵

- Sharon Mizota, “Metadata Isn’t Neutral: Addressing Orientalism and Patriarchy in OpenGLAM Art,” Medium, March 4, 2022, https://medium.com/metadata-learning-unlearning/metadata-isnt-neutral-addressing-orientalism-and-patriarchy-in-openglam-art-fb42bff7b93. ↵

About the Author(s): Marci Kwon is Assistant Professor of Art and Art History at Stanford University, where she also codirectors the Asian American Art Initiative with Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander. She is the coeditor of the Martin Wong Catalogue Raisonné.