Digital-Born Catalogues Raisonnés and Networked Art Histories

PDF: Voelker, Digital-Born Catalogues Raisonnes

Catalogue raisonné projects published solely in hard-copy formats represent more traditional—dare I say, market-driven and sustaining—approaches in the field of art history, whereas digital iterations might enable a reimagining of the genre itself. As a form, the catalogue raisonné obviously privileges maker-centered methodologies and, in paper versions, especially affirms positivist approaches by aiming to embody the authoritative, final reference on a given artist. Such print projects often materialize this authority through the inclusion of heavy, oversize tomes, luxurious color illustrations, and multiple volumes. As physically manifested in the outcome, these scholarly enterprises are time consuming, expensive, prestigious, and not intended to be (at least frequently) revisited or redone. Digital-born editions, in contrast, are flexible, living, and adaptive, enabling the incorporation of, or at least connection to, other critical questions beyond production. When digitally conceived, could a catalogue raisonné exist in a larger network of methodological concerns, spaces, and epistemologies that might expand both the stakes and the number of stakeholders involved?

As traditionally conceptualized, the catalogue raisonné demonstrates the Eurocentrism of our discipline in that it champions particular constructions of maker (the individual creator) and elevates certain media (those historically promoted in Western art academies). As a historian of photography and nineteenth-century visual culture, for example, I rarely use this form of scholarship in that it infrequently confronts the methodological concerns of my research. Focusing on photographic representations of Indigenous American Peoples both made and circulated across the Atlantic World, my work engages with authorship—and simultaneously notions of authority itself—as laden with power dynamics and as fraught, contested, and necessarily open to reclamation. Much more central to the questions this type of material demands are the histories of the sitters and the colonial structures in which they operated when these objects came into being and through which the works have circulated since.

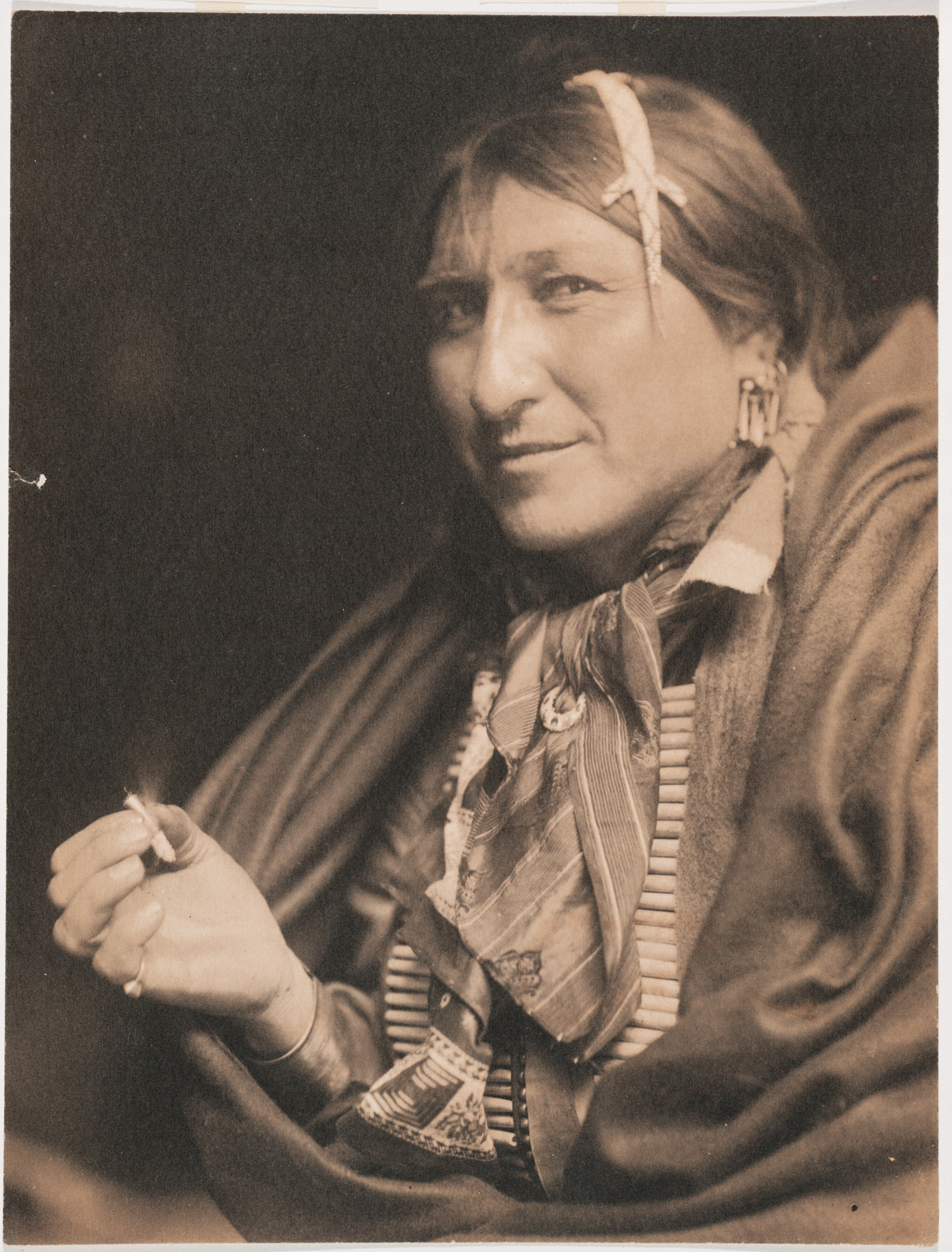

Indeed, I have found in my projects that reception and reengagement—whether visual, material, or both—conveys a much more complex, urgent set of meanings than the unilateral focus on maker. Of course, certain types of material remain more compatible with particular interpretive frameworks than others, but an example demonstrates the possibilities that bridging such inquiries with a networked approach might enable. While far fewer photographers are the subjects of catalogues raisonnés than practitioners in other media (such as painters or sculptors), those that operated squarely within the discursive space of the fine arts are most likely to be considered. Gertrude Käsebier might serve as a candidate; Alfred Stieglitz, to whom she was connected through the Photo-Secession, for example, is one of the few photographers who has been the subject of such a project.1 One of Käsebier’s most renowned bodies of work is a group of portraits of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performers made in her New York studio while the show came through the city on tour in 1898 (fig. 1). The exquisitely crafted platinum prints, many of which contain her red Arts and Crafts–style monogram at bottom left, demonstrate her virtuosity in both the visual and technical aspects of the medium. Her well-known pictures of Joe Black Fox capture the illumination of his face and various textures of his regalia in the nuanced tonal range and matte saturation of the platinum process.

If these works embody Käsebier’s participation in movements seeking to codify photography as a fine art at the turn of the century, they equally attest to the survivance of Indigenous Peoples in the US assimilation era through participation in racialized performance cultures like wild west shows. Black Fox, as well as many of the performers who worked with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West since its inception in the early 1880s, were Lakotas, recruited from Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and neighboring agencies. In these communities today, the travel and participation of ancestors with such troupes shapes collective and family memories of the early reservation period. Accordingly, photographs like Käsebier’s and other materials related to wild west shows reside—some materially and others digitally—in reservation-based archives, where they function in relation to local meanings, uses, and practices of history keeping. I am currently a collaborator on a planning grant exploring these issues entitled “Wičhóoyake kiη aglí—They Bring the Stories Back: Connecting Lakota Wild West Performers to Pine Ridge Community Histories,” funded by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission of the National Archives.2 The project supports the development of a collaborative digital edition to ultimately be housed at Woksape Tipi, Oglala Lakota College. Given the increasing concern in American art history to both represent and engage the myriad communities that have shaped—and continue to shape—the contemporary United States, it seems that a methodology steeped solely in an individual creator limits the multivalent stories we might, and, I would argue, should, tell.

The flexibility of digital-born platforms, with their ability to morph and evolve over time, also allows for historical analysis that is adaptive to the concerns a contemporary moment demands. An example of a maker-centered digital-humanities project that incorporates this multivocality and responds to the urgent questions the works present today is “Casting Identities: Race, American Sculpture and Daniel Chester French.”3 Commissioned by Chesterwood in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, the project is part of the National Endowment for the Humanities grant “For the People and by the People: Transforming National Trust Historic Sites through the Humanities,” which is being organized by Research Specialist Emily C. Burns, along with Meagan Anderson and Olivia von Gries, two PhD students in the art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma.

“Casting Identities” aims to contextualize French’s work within both historical and current debates related to monumental public sculpture, commemoration, and constructions of race. Based on Omeka and with embedded Thinglink photo tours of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 and of the Four Continents sculptures in lower Manhattan, the initiative serves as a particularly good model for the possibilities a digitally conceived and single-artist project presents when bridging multiple methodologies, voices, interpretations, and time periods through a networked approach. For example, in Anderson’s essay for the site, she uses the digital format to virtually move us around French’s sculpture of “America” from the Four Continents, enabling a more nuanced consideration of how it constructs a narrative of racialized national identity.4 With this photographic tour, we can circle the sculpture to focus closely not only on the dominant white classical allegory of America at its center but the Indigenous figure peeking over her shoulder at left or the broken piece of pottery at the sculpture’s back base (fig. 2). Using stitched photographs, Anderson was able to recenter this broken pottery, allowing for its identification as Alabama River pottery (created c. 1500–1700), regularly being expropriated from Southeast gravesites at the time French produced this work.5 The technology therefore facilitates critical connections between the sculpture’s narrative of Indigenous disappearance and the looting of Native burial objects now protected under Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

Given the multivocal and adaptable potential of digital humanities projects, demonstrated by the examples given here, it seems that catalogues raisonnés conceived entirely in this format could integrate a number of these approaches to confront some of the most pressing concerns of American art history now. The format enables a refiguring and opening of this genre of scholarship that can reflect the questions and methods that have transformed the field itself. Digital-born projects and the interconnections they enable formally mesh almost seamlessly with the increasing turn to networked approaches across our discipline, which chart webs of agents, materials, and spaces in tracing our objects of study.

Cite this article: Emily L. Voelker, “Digital-Born Catalogues Raisonnés and Networked Art Histories,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17354.

Notes

In addition to the projects cited here, the author would like to thank Christine Garnier and Naomi Slipp for their thoughts regarding this topic, as shared during the College Art Association annual meeting in New York in 2023.

- See Sarah Greenough, Alfred Stieglitz: The Key Set; The Alfred Stieglitz Collection of Photographs (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art; New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2002). The project is also available online as a digital edition through the National Gallery of Art: https://www.nga.gov/research/online-editions/alfred-stieglitz-key-set.html. ↵

- The project is referenced in relation to these National Archives grants: “New Round of Mellon Grants,” NHPRC News, October 2022, https://www.archives.gov/nhprc/newsletter/october22. ↵

- “About,” in Emily C. Burns, Olivia von Gries, and Meagan Anderson, Casting Identities: Race, American Sculpture and Daniel Chester French, https://eb-omekadev.oucreate.com/about. ↵

- Meagan Anderson, “An Introduction to French’s Four Continents,” in Emily C. Burns, Olivia von Gries, and Meagan Anderson, Casting Identities: Race, American Sculpture and Daniel Chester French, accessed April 10, 2023, https://eb-omekadev.oucreate.com/exhibits/show/four-continents/introduction-to-french-s-four-. ↵

- Thank you to Emily C. Burns for sharing the information and findings detailed here regarding what the digital format has enabled in expanding interpretation of French’s work. ↵

About the Author(s): Emily L. Voelker is Assistant Professor of Art History at University of North Carolina Greensboro.