Seeing Flora’s Profile as Portrait

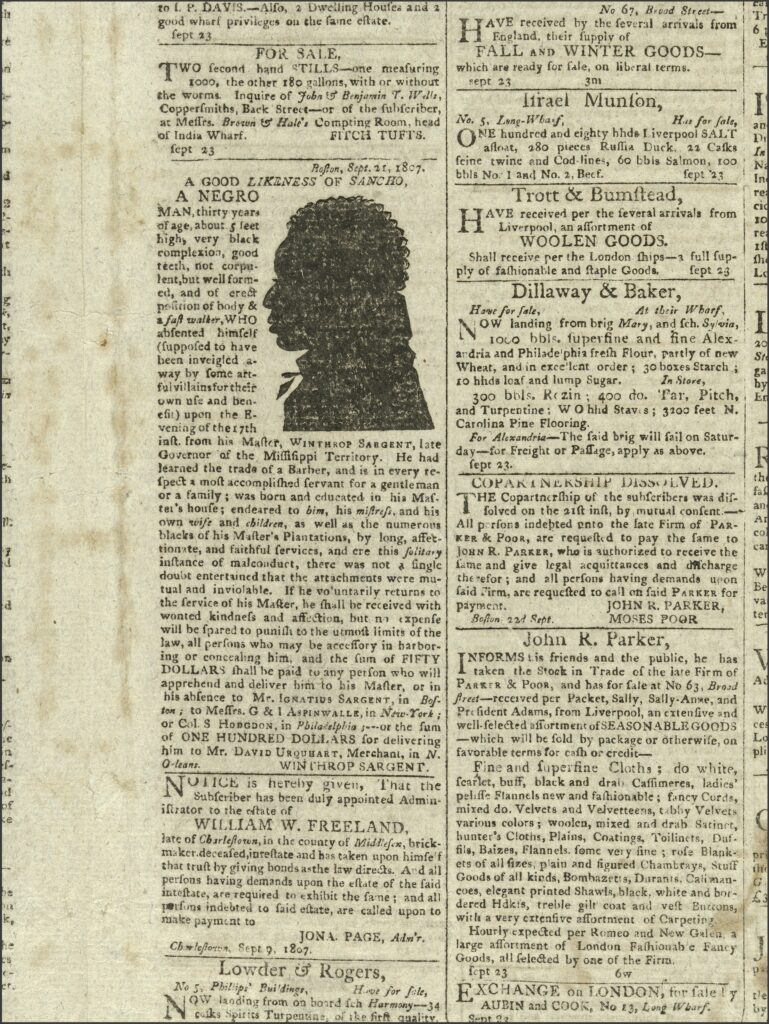

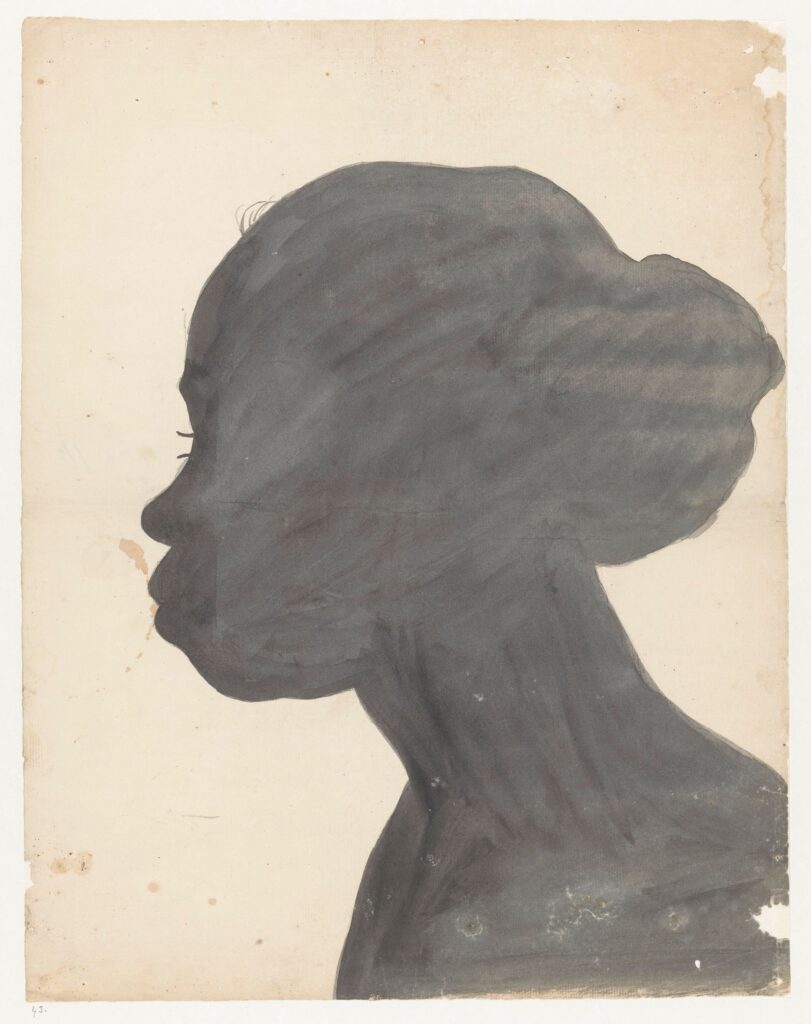

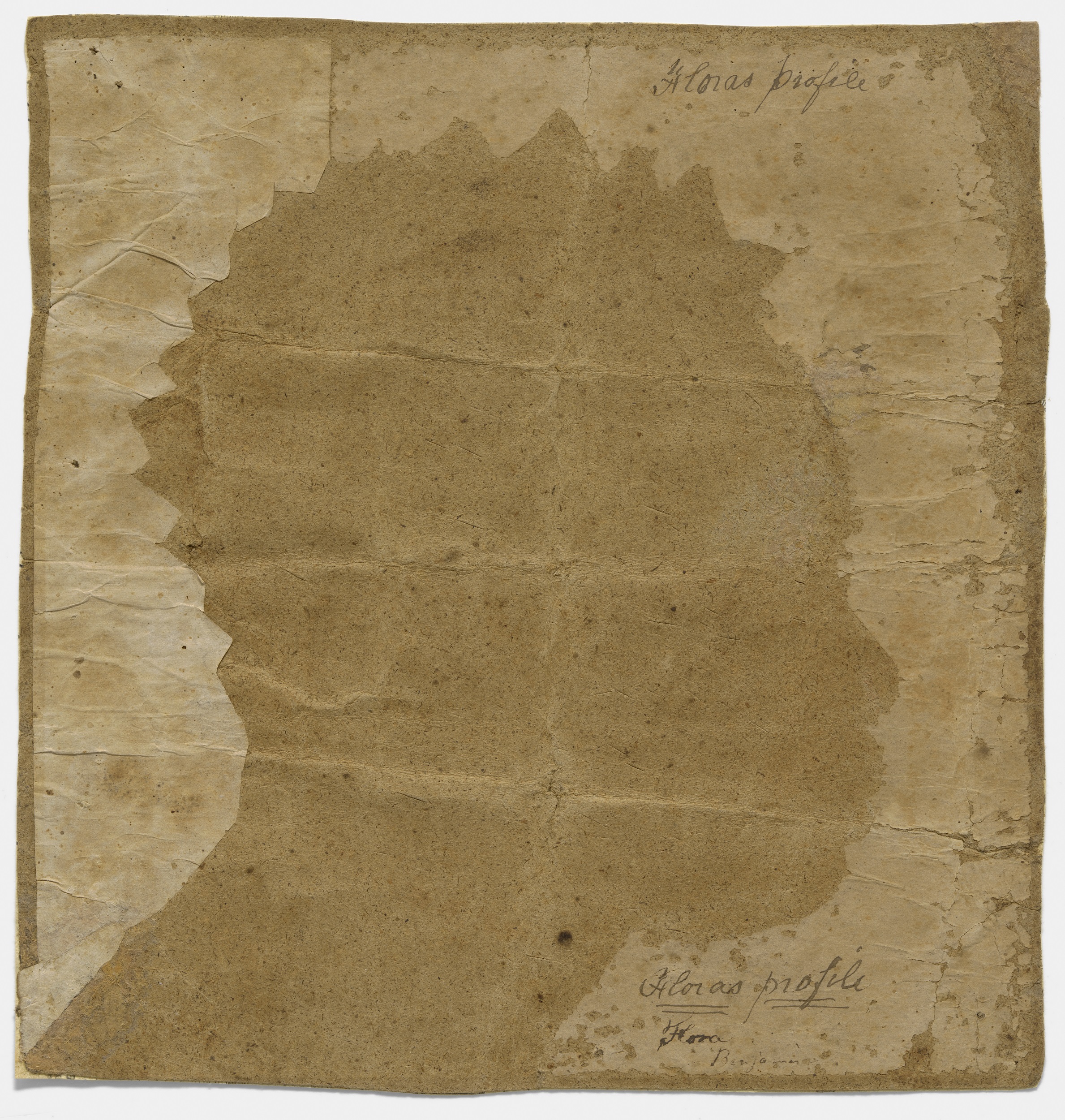

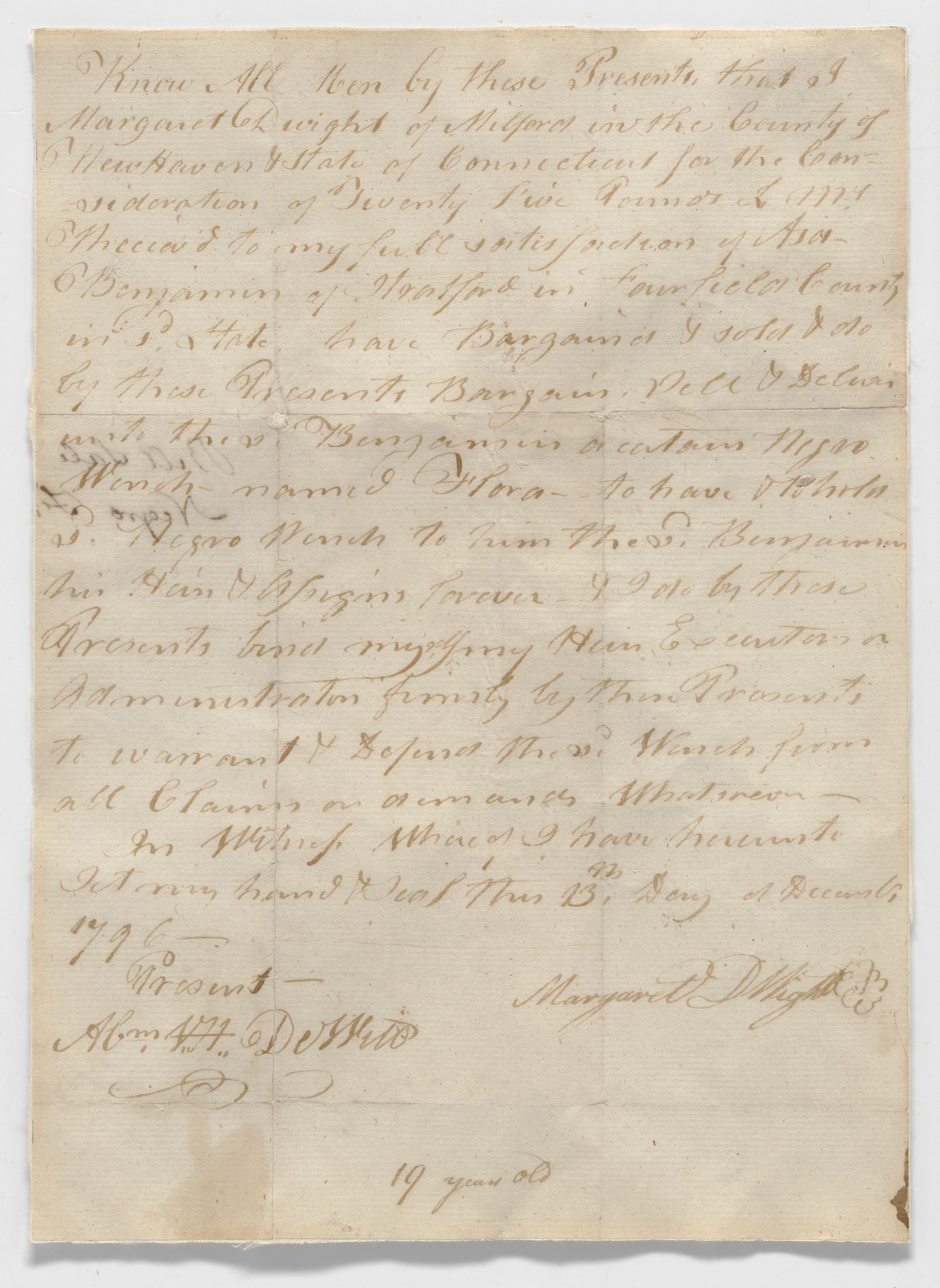

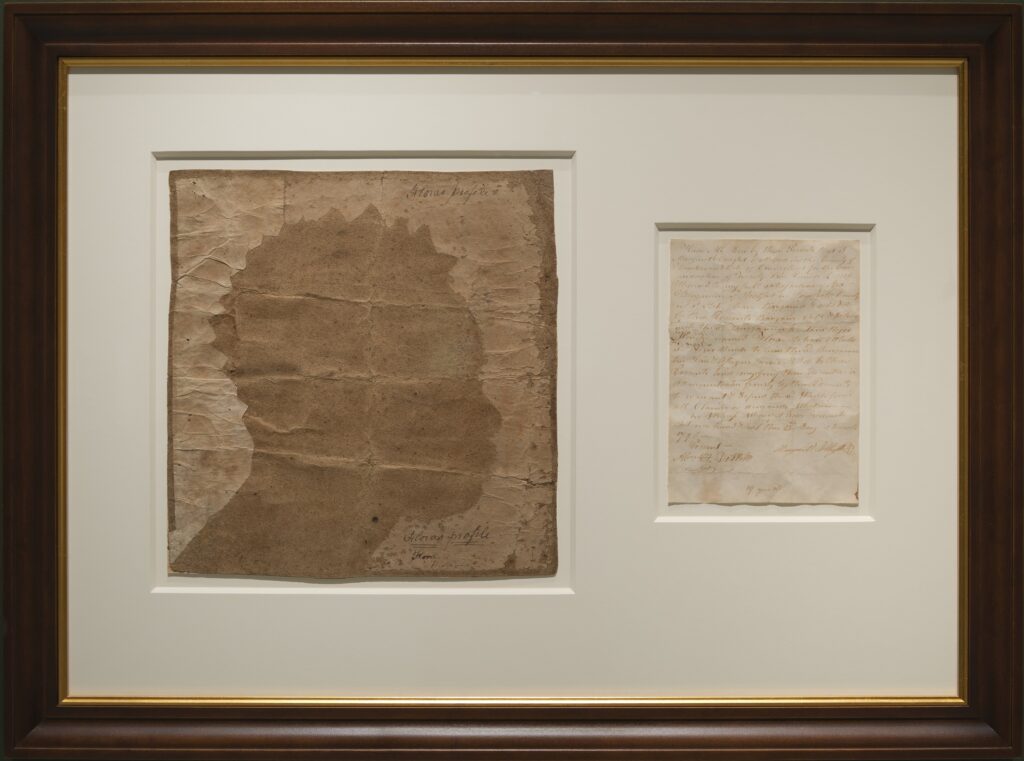

The silhouette of Flora by an unidentified artist gripped visitors to the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s 2018–19 exhibition Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now, curated by Asma Naeem (fig. 1). The profile view shows a young woman, apparently of African descent, turned to her left. Rendering her head and the column of her neck, the silhouette exactingly depicts the curves of her face. At the top of her forehead, the line rises into triangles forming a sharply undulating edge, offering a more abstracted vision of her hairstyle. The silhouette has long been associated with the December 13, 1796, bill of sale marking Flora’s legal transfer, at age nineteen, from Margaret Dwight of Milford, Connecticut, to Asa Benjamin of Stratford, Connecticut, for twenty-five pounds (fig. 2). The two pieces have been framed together for decades, forming a perverse pendant, an image of an individual woman and a text documenting the terms under which she was sold as a commodity (fig. 3).1 Linking them causally, scholars typically envision a scene of destructive creation. Angela Rosenthal and Agnes Lugo-Ortiz, for example, see the sitting as “a potentially terrifying experience” for Flora, “a flattening out and commodification of the self, rather than enabling or ennobling.”2 Far from a portrait conveying subjectivity, the silhouette, by this logic, functioned as an extension of the white objectifying gaze. It was both a substitute for purchaser Benjamin’s visual inspection of Flora’s body at sale and a tool of potential surveillance should she try to self-emancipate: a documentary record of her appearance for her enslavers’ use.

Yet there is no evidence to indicate that Flora’s silhouette was made to serve the bill of sale, and no reason to assume that it was. Enslavers in general did not create visual images for purposes of sale, and nothing internal to the artifacts links them to each other at one specific moment in time. Nor is there documentation for when or how the two artifacts came to be associated with one another. In this essay, we aim to disentangle the two pieces and suggest a new framework for seeing Flora’s profile not as document but as portrait. Close analysis of the silhouette’s material and aesthetic qualities, together with new documentary research into Flora’s history, open up questions about who might have made her silhouette and what it might have meant to her and to them.3

Our research complicates recent scholarship exploring notions of “the slave portrait.” Rosenthal and Lugo-Ortiz, in fact, used their brief analysis of Flora’s silhouette in the introduction to their anthology, Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World, as an occasion for raising larger questions about the genre’s very possibility. Modern definitions of portraiture tend to assume the subject’s agency and, reciprocally, the painter’s aim to convey subjectivity; at minimum, as art historian Marcia Pointon puts it, the sitter is being “depicted for his or her own sake.”4 This flies in the face of chattel slavery’s logic of surveillance, bodily control, and denial of full humanity for Africans and African Americans. Following that logic to its end, David Bindman argues that the term “slave portrait” itself is an oxymoron.5 Using this literature as a point of departure, we first explore the interpretation of Flora’s silhouette as an object of possession on the part of her enslavers. We then question that interpretation, introducing the possibility of an African American maker. While material constraints and violence always mitigated Black freedom of expression under slavery, our research establishes the context in which a Black maker of Flora’s profile is not only possible but plausible. In exploring this evidence, we ask scholars to question the default assumptions that continue to shape the field of American art history about who could make art. As material culture specialists have long shown, enslaved and free African Americans articulated their creative vision in the material and visual fields of pottery, weaving, quilting, ironwork, cabinetmaking, stone carving, and others.6 And portraiture is no different. Scholars beginning with James A. Porter in the 1940s have documented a vibrant history of Black artists dating from at least the early nineteenth century.7

There are numerous candidates for a Black maker, as Flora lived in a network of African and African American kin and community. It is worth remembering that eighteenth-century Connecticut was a significant site of New England enslavement—second only to Rhode Island—a fact often forgotten despite decades of scholarship on slavery in the North.8 Just more than 3 percent of Connecticut’s late-colonial population were enslaved, their numbers concentrated on the coast. More than one-third of enslaved people in the colony were held in the counties of New Haven and Fairfield, present in every town in those counties, including Milford and Stratford, the sites of Flora’s enslavement. Slaveholding was endemic and stretched across white social groups and occupations. Historian Guocun Yang found that in 1776, nearly one quarter of Connecticut wills probated included at least one enslaved person as property (almost all were African or African American, but some Native Americans remained enslaved as well). In 1790, 70 percent of merchants held at least one enslaved person, as did half of ministers, deacons, justices, deputies, and wealthy farmers.9 A 1774 ban on the importation of slaves and a 1784 gradual emancipation law eventually ended the institution, but these had no impact on people like Flora, born before the emancipation law went into effect. Indeed, slavery remained legal in Connecticut until 1848, when the state became the last in New England to abolish it entirely.10

The ubiquitous presence of Africans and African Americans broadens the number of viable candidates for the maker of Flora’s profile. At the very least, it means we must question the accepted notion of a white maker. Our shift in default assumptions changes the calculus: if the maker and potential viewers did not conceive of the subject as slave first (not even “enslaved person”), then the profile is no longer a slave portrait. This is a significant move, most narrowly because Flora’s silhouette has become a kind of icon for the genre of slave portraiture, gracing the cover of Lugo-Ortiz and Rosenthal’s 2013 volume, for example, and even for slavery more generally, adorning the 1995 paperback edition of historian Edmund S. Morgan’s 1975 classic, American Slavery, American Freedom.11 But more broadly, our grounded speculation raises questions about how scholars address gaps in the archive of slavery, particularly the visual archive, and asks us to think about what we are willing to accept as assumptions in the face of those gaps.

Our essay moves from what can be determined to what can be surmised to what can be imagined. In part 1, we disentangle the silhouette from the bill of sale. In part 2, we consider the possibility that the silhouette was made for the white enslavers, independent of the moment of Flora’s sale, and preserved by them. In part 3, we expand the range of historical actors to consider alternative possibilities for who made Flora’s silhouette, including African Americans in her family and in her communities. Finally, in part 4, using what is known about enslaved African Americans’ occupation of and claiming of domestic space in slaveholding households, we reflect on who might have viewed and kept Flora’s silhouette, in what spaces, and for what purposes.

These paths are speculative and hypothetical but grounded in documentary research. We use these possible histories to chart different routes to enslaved agency by positing potential makers, users, and preservers of Flora’s profile. We are guided by the work of Saidiya Hartman and her example of scholarship that imaginatively reconstructs the experiences of subaltern groups who were often denied the ability to control images of themselves or the recording of their own histories. As she describes it in her recent work Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval, scholars’ search for Black subjectivity necessitates the creation of “an archive of the exorbitant, a dream book for existing otherwise” to produce “a counter-narrative liberated from the judgment and classification that subjected young black women to surveillance [and] punishment.” Inspired by Hartman, we present the reader with multiple scenarios. None of these are definitive, but all take into account the agencies that run underneath, alongside, and—often unacknowledged—within recorded texts, legal documents, and surviving images.12 We do not intend to convince readers of one particular scenario; instead, we ask readers to sustain the possibilities of all of them. We use detailed analysis of the sources that survive—documentary, material, and visual—to create a space for Flora’s subjectivity as well as those of possible Black makers and preservers, while respecting what cannot be recovered and what must be left unknown and unstated. Our subject positions as white scholars make it particularly important for us to remain attentive to possible biases and to be clear why and how we have come to certain conclusions so that we do not inadvertently inscribe our own scholarly desires—or our own voices—onto Flora. Flora is therefore a constant presence in the shifting histories we present, her image the guiding force and her life story the driving narrative, yet she herself—her hopes, dreams, loves, and sorrows—remains largely unknown to us.

Part 1

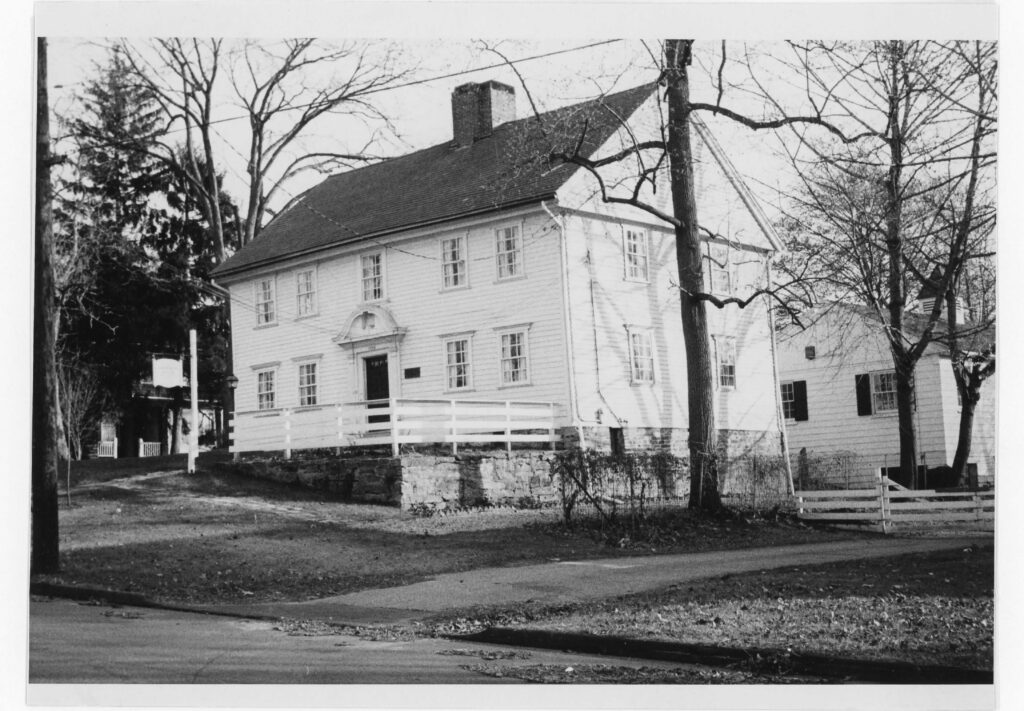

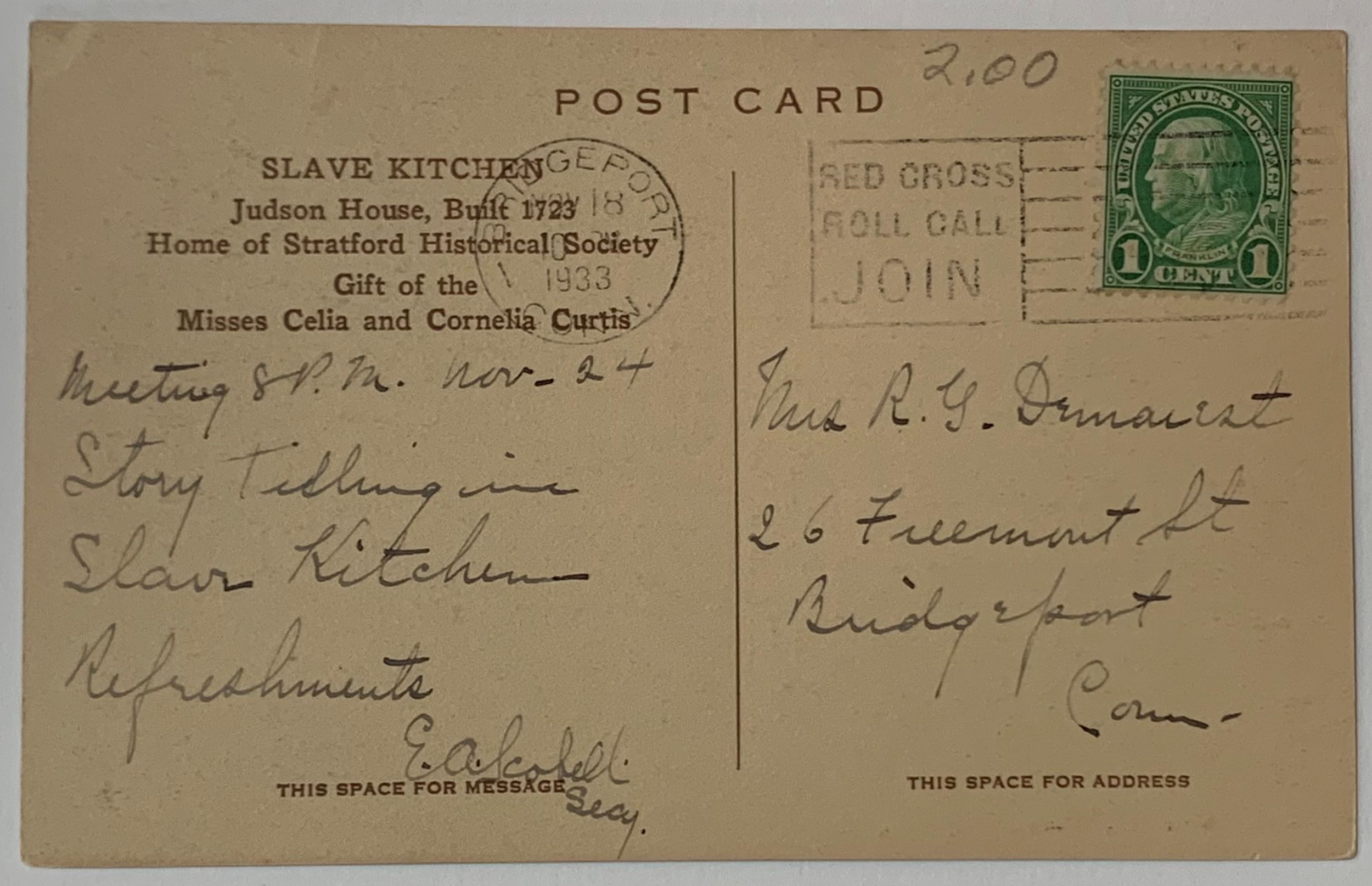

The silhouette’s provenance and recovery are understandably murky. It was apparently discovered in the cellar kitchen of the eighteenth-century Captain David Judson House in Stratford, Connecticut (fig. 4)—the same town where Flora’s purchaser and enslaver Asa Benjamin resided and only three miles from Margaret Dwight’s hometown of Milford. Stories vary as to whether the profile was stowed away in a drawer or hidden inside a wall of the kitchen. It is not known who placed the silhouette there, who put it together with the bill of sale, or when that pairing happened. It is also not known when they were discovered, though it was probably after 1925, when the Stratford Historical Society acquired the house.13 The first reference to the silhouette we have found is a 1968 Stratford Historical Society newsletter. It describes the silhouette and bill of sale as framed together and displayed in the Judson House cellar kitchen. This space was referred to as the “slave quarters” or “slave kitchen” during tours and on postcards from the very beginning of the society’s curation of the house in the 1920s. We do not know when they were framed together or first went on display there; they are not visible in the postcard photographs of the cellar kitchen dated 1926 and 1933 (fig. 5), though they could be out of the photographer’s frame. But once they were placed on view there, the framing and setting helped cement the idea that the visual artifacts were made in common purpose, an idea that has shaped subsequent scholars’ interpretations of Flora’s profile.14

We must recognize, however, that there was no reason for a silhouette to accompany a bill of sale in the first place; sellers and buyers saw no need for visual documentation. Enslavers often “inspected” enslaved people before purchase in order to assess their health, appearance, and perceived capabilities. Benjamin had ample opportunity to see Flora in person if he so desired. His house near Yellow Mill Creek in Stratford15 was only eight miles west of downtown Milford, where Dwight, as a recent widow, was likely staying with her brother Abraham DeWitt, who witnessed Flora’s bill of sale.16 When enslavers made purchases sight unseen, they generally trusted the word of white sellers or agents.17 DeWitt may have helped arrange Flora’s sale, for example, either through correspondence or through personal interaction with Benjamin. If so, following period norms, Benjamin would have largely relied on DeWitt’s oral or written account of Flora. Even in their written descriptions, sellers and buyers defaulted to broad categories of laborer: for example, a “hand” for a field worker or “wench” for a woman of child-bearing age. Indeed, this latter term was used on Flora’s bill of sale. As Walter Johnson has shown, buyers also relied on their own illusion of mastery in the market, projecting their own fantasies onto the bodies of enslaved individuals. Visual representation of individuals for the purpose of soliciting sale therefore seems to have been anathema. For the same reasons, bills of sale usually included no more than a name, age, and gender, with little individual detail and never an image. In addition to our own archival experience, we recently surveyed sixteen historians of North American slavery, especially those with a focus on New England. All responded, with none having ever seen or heard of any visual depiction of any kind accompanying a bill of sale in North America or elsewhere.18

There is one partial exception to this practice, a pair of images probably created for the purpose of soliciting sale, though not physically associated with a bill of sale. This single example came much later, only with the proliferation of photography and specifically with the creation of durable tintypes that could be mailed or carried without fear of breakage. In about 1858, a young boy in Texas was made to stand unclothed and to smile for a pair of photographs showing his entire body, front and back. Descendants of his white enslavers, in whose possession the tintypes remained until fairly recently, report that the family’s oral tradition asserts that the photographs were taken for the purposes of the boy’s sale. Indeed, analysis of their formal qualities by historian of photography Matthew Fox-Amato supports this narrative.19 It is difficult to imagine other uses for the tintypes except sexual exploitation, which was, of course, twisted inherently into the logic of slavery and the slave market in the first place.20 But Flora’s silhouette did none of the horrifying visual work that these tintypes accomplished. It did not expose any of her body to scrutiny, and while silhouettes did produce a kind of accuracy later attributed to photography, this physical information was limited to the outline of her face and head.

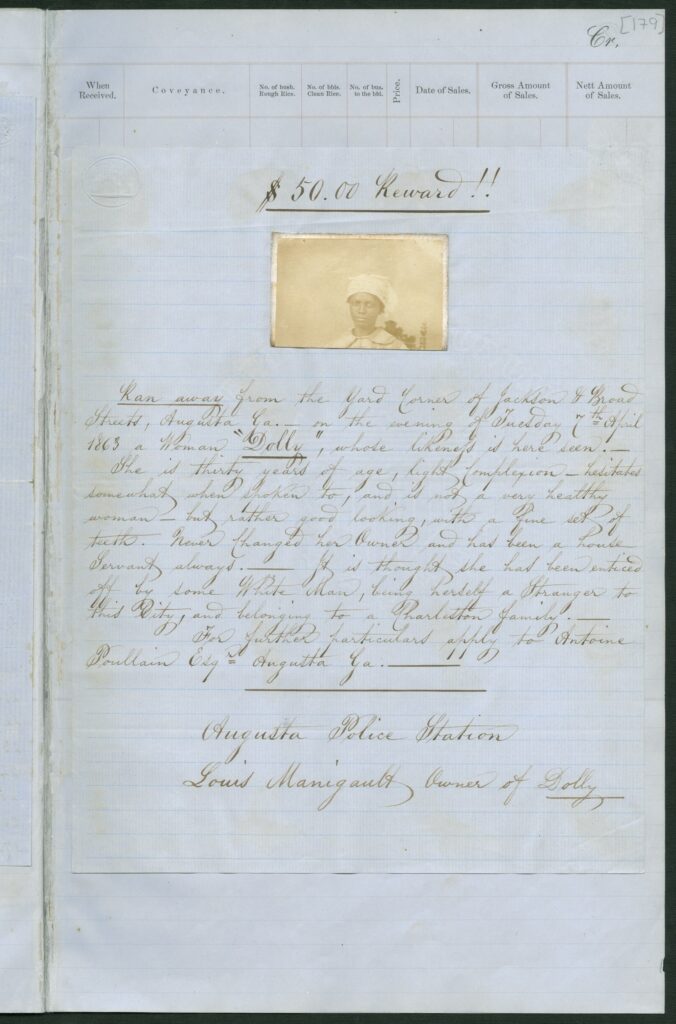

The silhouette’s other proposed origin is as insurance against Flora’s self-emancipation after her transfer to the Benjamins. Art historian Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, who has offered the most thorough analysis of Flora’s profile to date, has interpreted it as a tool for the Benjamins’ “use in active surveillance,” likening it to “the contemporary police mug shot.”21 While there is a logic to the idea of creating and preserving a likeness for this purpose, there are only two known instances of depictions of specific enslaved people added to “runaway” advertisements: Sancho, whose silhouette was included in an 1807 advertisement in a Boston newspaper (fig. 6), and Dolly, whose photograph was appended to a handwritten 1863 broadside her South Carolina enslaver assembled himself (fig. 7). While Sancho’s printed profile has also been interpreted as an act of surveillance, its formal qualities imply that it was a wood-engraved copy of a professionally produced silhouette with prior use in a domestic capacity, perhaps signaling the white family’s imagined familiarity with Sancho. Similarly, Dolly’s photograph was cut down from an already-existing carte de visite her enslavers had commissioned. In each case, the image had been created earlier for other purposes and only later repurposed into a tracking device.22 These two outliers notwithstanding, “runaway” ads routinely relied solely on textual description, though sometimes accompanied by a brutally generic printer’s icon alerting readers to the advertisements’ function but not purporting to represent any individual freedom-seeker.23 If Flora’s silhouette were, in fact, created to document the moment of her sale or to thwart her escape afterwards, it is an absolutely unique and unprecedented artifact for its era.

Even if a buyer were to feel a visual rendering of this financial transaction necessary, an image produced around the time of sale would likely have been a simple outline sketched on the same or similar paper as the bill of sale. The bill of sale is written on laid paper, a relatively expensive, often-imported paper used by elites and merchants for letter writing. Its watermark, “BAND / 1795,” identifies it as produced in Somerset, England. Flora’s silhouette, by contrast, involved different materials and entailed a lengthier process of construction, one shaped by aesthetic considerations. The recent inclusion of Flora’s silhouette in Black Out spurred our initial conversations about its creation and gave us the opportunity to discuss it with the Smithsonian conservator to better understand its physical composition and mode of manufacture.

To create the profile, the unknown maker held up or affixed two sheets of paper to a wall, traced the profile across them, cut it out, and pasted the two pieces onto a darker-colored paper that served both to support and complete the silhouette. These cut sheets are of wove paper, used for daily letter writing and for other common uses, including professionally produced silhouettes. A third type of paper, a darker and rougher millboard, forms the silhouette’s background support.24 A heavy, unfinished paper manufactured from ground-up ropes, millboard is commonly used in book boards, where it is covered with a finer paper to make the binding. It is an unusual choice, perhaps one employed of necessity from cast-off scraps as well as for an aesthetic purpose—its brown tones setting off the cream cut profile. The possible constraint of working with make-do materials appears again in the wove paper. Flora’s silhouette is constructed from three pieces of paper joined together: the two larger pieces form a vertical seam visible above Flora’s head, and a small third piece was added at the lower left corner. That fragment completes the line of Flora’s neck, seemingly an ad hoc solution to the problem of size but also an artistic choice.25

The paper’s careful mounting on millboard to form the silhouette further heightens the sense of the maker’s aesthetic attention. The profile was cut smaller than the support and placed so that a darker border appears on all sides, echoing the effect of a wooden frame (except where the third bit of paper was added to Flora’s neck).26 That deliberate choice of framing suggests that the image was originally conceived to be displayed and viewed on its own, not folded together with other documents or tucked into the pigeonhole of a desk. The millboard’s stiffness—it measures about one millimeter thick (about the same as four standard playing cards stacked together)—along with its contrasting use as a framing device strongly suggest that Flora’s silhouette was intended initially as a standalone object and one that would literally stand up on its own. Perhaps it was created for mounting on a wall or for propping on a mantle, like cabinet cards a century later. At some point, however, it was folded. But even these creases point toward the separate initial usage and storage of the two pieces. Flora’s silhouette was folded roughly in half and then in uneven quarters, leaving visible lines that do not correspond to those found on the bill of sale, which follow a fold pattern typical of a letter—in thirds vertically, then thirds horizontally. Given the silhouette’s bulky mass when folded, it is difficult to imagine it being stored alongside letters or legal documents. Its folds perhaps represent the keeping of a secret or the necessities of portability, rather than filing or record keeping. The greater degradation and loss of the cut paper along the silhouette’s right side suggest that this edge was exposed once folded and supports the idea that the artifact was stored for a relatively long period of time in this bundle-like format, possibly separate from the bill of sale for most of its early life.27

One final connection made between the bill of sale and the profile has been the four inscriptions on the silhouette: “Flora’s profile” (written twice, once with double underlining), “Flora,” and “Benjamin.” Conservation analysis was not able to determine the dates or sequences of the inscriptions. All are in iron-gall ink, common through the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. While the handwritten name “Benjamin,” added just below “Flora” (perhaps in a different hand), must date, at earliest, from her 1796 relocation to the Benjamin household, this inscription could have been added to the work at any time after that. The others could have been inscribed at any point after the silhouette’s making, which may or may not predate the bill of sale. The unknown dating of these inscriptions, their repetition, and the likelihood of more than one hand together suggest the possibility of multiple inscription campaigns by more than one author. In the nineteenth century, silhouettes were often marked with paratext identifying sitters’ names, listing their spouses or children, and giving their life and death dates. Such information was unnecessary for those who could identify the sitter but was intended for future viewers; it was sometimes included retrospectively, even well after the sitter’s death. It is easy to imagine a sequence in which the Benjamin surname was added to the profile after the other inscriptions to identify Flora in relation to the Benjamin family. What at first seem to be Asa Benjamin’s marks of possession appear less certain when considering common practices of silhouette marking.28

Part 2

Once we let go of the assumption that the silhouette was made in service of the bill of sale, we can explore other possibilities, uses, and audiences. The December 13, 1796, bill of sale records Flora’s age as nineteen, putting her birth in 1777 (or possibly the last few weeks of 1776). Given Flora’s youthful appearance in the portrait, she was likely between her teens and early twenties, meaning the image could have been created as early as, say, 1790, several years before the sale, or as late as perhaps 1810, well after the sale. Taking these suppositions as our starting point, we see several possibilities for when and where the portrait might have been taken.

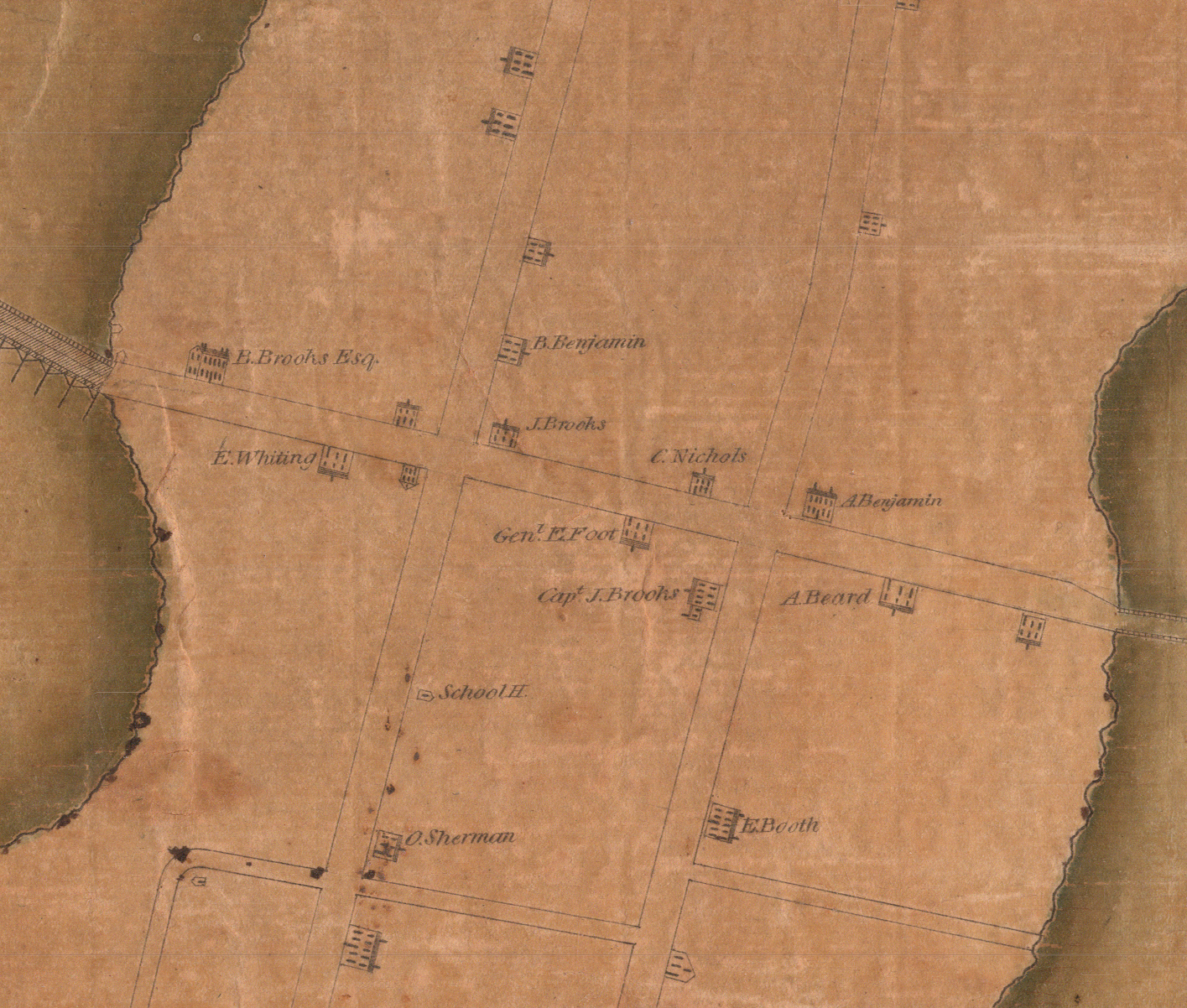

To begin, let us consider that the profile could have been made after Flora was in the Benjamin household, where she likely remained until her death. Asa Benjamin owned a house and operated a ropewalk in Stratford at New Pasture Point, on the west bank of Yellow Creek just across the Yellow Mill Bridge. His house is visible in a detail of an 1824 map drawn by H. L. Barnum and engraved by Nathaniel and Simeon Jocelyn (fig. 8). While the impressive five-bay, two-story house is recorded on the map, the ropewalk and wheelhouse, which once stretched between the main house and the river, were no longer extant and are not pictured. In the 1790s, however, the facility was a significant enterprise where male workers processed flax and hemp, spinning it into rough yarn and then twisting strands to form rope that Benjamin supplied to local shipbuilders and captains. Ropemaking required skilled physical labor; makers walked on the ropewalk with the rope looped around their waists, making sure that the fibers stayed in the proper position and at the right tension for a wheel in the wheelhouse to bind them together. While he had established the ropewalk before 1791, Benjamin expanded it greatly over the next few years. His 1790 household included only three members; by 1800, it numbered seventeen total, including, aside from himself and two young sons (both under ten), three white boys aged ten to fifteen, five white boys and men aged sixteen to twenty-five, and two white men aged twenty-six to forty-four. All were likely ropewalk apprentices or workers like John Jones, whom Benjamin advertised in 1804 as a fugitive “indentured apprentice.” Housing ten white male workers suggests that Benjamin was one of the most prominent of Milford’s several rope makers.29

Benjamin’s purchase of Flora in 1796 was part of his amassing of capital, economic and social. His expansion of the ropewalk, the birth of his first child in 1791, his commissioning of family portraits from local artist William Jennys in 1795 (figs. 9–11), and the purchase of Flora the next year all testify to Benjamin’s growing stability and attempts to cement his social prestige. But his fortune did not last. In 1806, he filed notice with the state of Connecticut that due to “various losses, and misfortunes, he has become insolvent.”30 Benjamin may have felt that foreign competition hastened his downfall; in 1801, he had petitioned Congress to impose duties on imported rope.31

Given Asa Benjamin’s 1806 insolvency, it is possible that he sold Flora at that point to help lessen his economic distress. There is uncertainty surrounding Flora’s death date. A Benjamin family member is said to have recorded the death of an enslaved woman named Flora on August 31, 1815, but we have not been able to determine the original source for this statement or whether it refers to the same woman depicted in the silhouette.32 If this date is correct, then Flora died at age thirty-eight, after nineteen years in the Benjamin household. Federal census records, however, suggest that Benjamin held onto Flora despite his financial setback and that she lived until after 1830. An enslaved woman of the correct age range is listed in his household for 1820 and 1830, when Flora would have been forty-three and fifty-three, respectively. Since it is very unlikely Benjamin would have purchased anyone covered by Connecticut’s gradual emancipation law—those born after 1784—much less someone in these age ranges, it seems likely that Flora remained in the household.33 If she is the person represented in the 1820 and 1830 censuses, then she was enslaved by the Benjamins for more than thirty years.

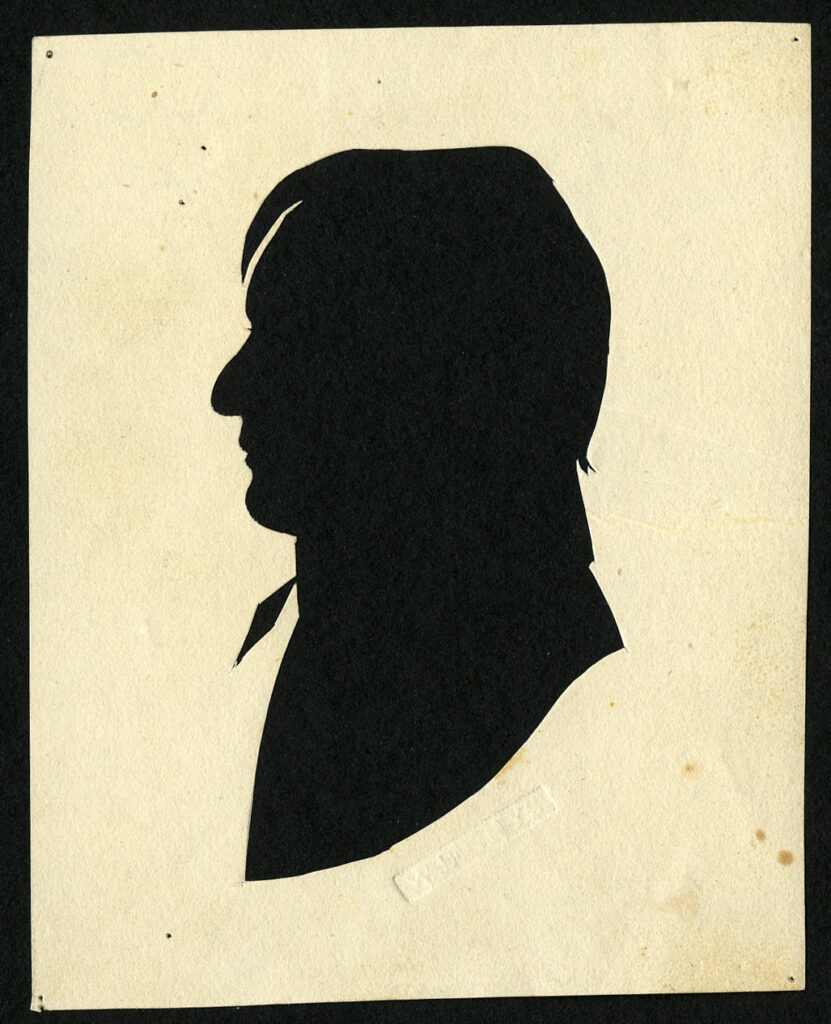

What would Flora’s visual experience have been within the Benjamin household? What visual artifacts did the Benjamins own; what relationships did they have with silhouettes; and what images would Flora have encountered as well? How familiar would she have been with the profile format before hers was taken? The survival of the white Benjamin family’s visual artifacts spurs us to consider Flora’s responses to them. As we have mentioned, just one year before Flora’s 1796 purchase, Asa and Hannah Benjamin, along with four-year-old Everard, sat for portraits by local artist Jennys. These paintings, especially those of Asa and Hannah (figs. 9 and 10), show Jennys’s use of a single strong light source, causing his sitters’ noses to cast dark shadows onto their faces. As his interest in shadow suggests, Jennys was also a silhouette artist, and beginning in the 1790s he produced profile views, such as this hollow-cut profile of an unidentified man (fig. 12). The Benjamin family might well have had silhouettes taken by Jennys or another artist, though none are extant. This seems likely, given the fact that the parents and eldest son had their likenesses taken but no paintings have survived of the younger Benjamin children. Silhouette takers were common in the region; Peter Benes estimates that there were more than thirty profile artists in New England using mechanical equipment (as Jennys did) between 1790 and 1810.34

Flora, then, was likely familiar with professionally made silhouettes, either from those possibly displayed in the Benjamins’ or their neighbors’ households or even from watching a silhouette cutter, such as Jennys, at work. If a professional silhouette artist produced profiles of the Benjamin children, however, it is unlikely that the same artist also created Flora’s image. Flora’s profile does not resemble those done by professionals, who relied on a mechanical “physiognotrace” and a practiced hand to cut silhouettes almost the scale of miniatures, usually measuring from two to four inches in height.35 Flora’s profile is thirteen inches tall, close to life-size, and was likely taken by candlelight or firelight against a wall. It therefore more closely resembles popular amateur-cut profiles. Most of those that survive from the eighteenth century feature political elites, including one of George Washington (fig. 13). Supposedly made over tea by Samuel Powel, a prominent merchant and Philadelphia mayor, this example attests to the fashionableness of amateur silhouette taking at social gatherings.36 We might imagine one of the Benjamins, inspired by their experience with Jennys’s work, having Flora sit for them as they tried their hand at the practice.

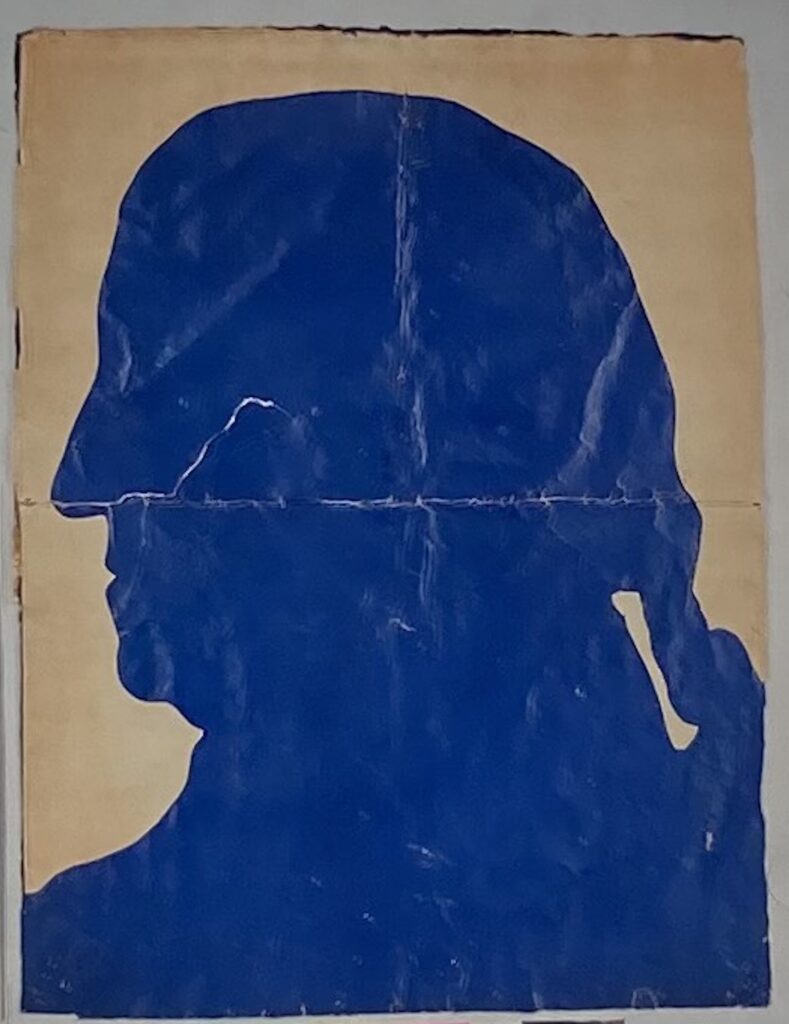

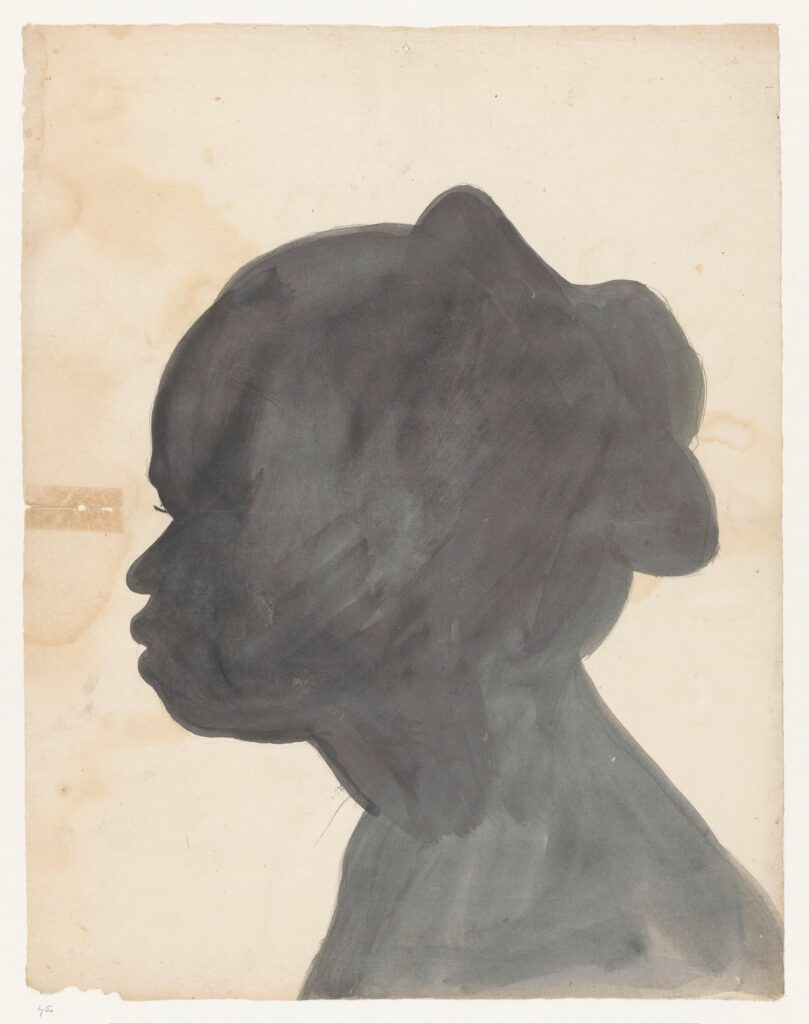

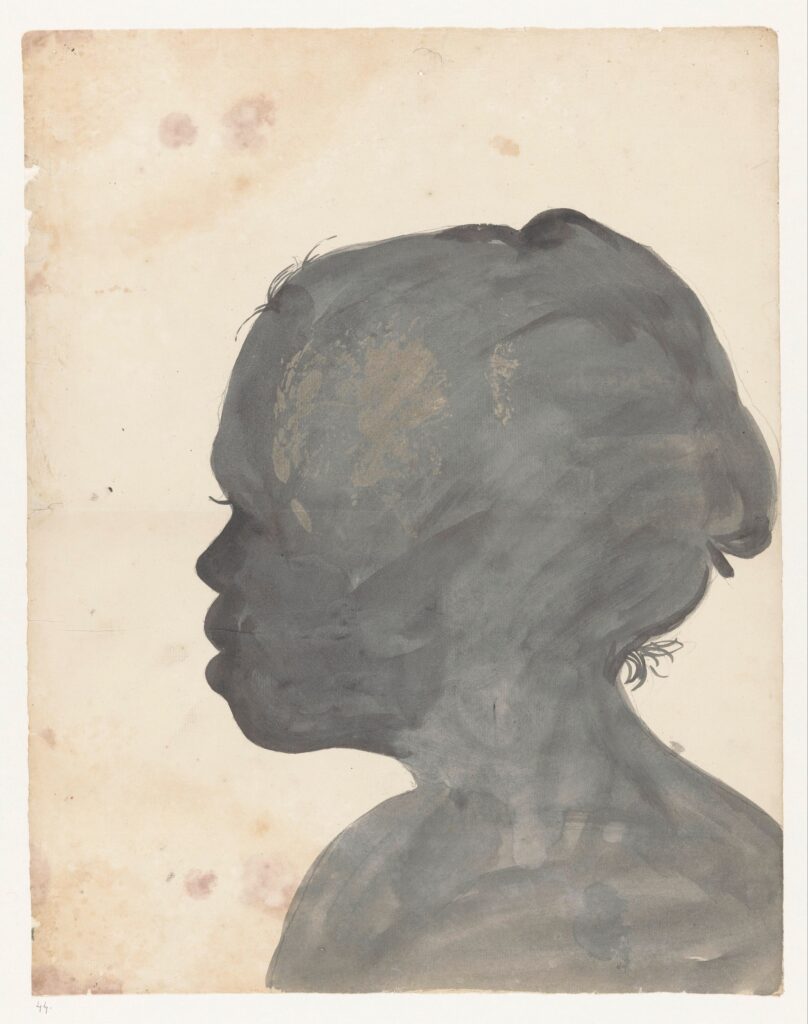

This scenario seems more plausible when we consider a second silhouette of a second enslaved Flora, who lived half a world away at around the same time. Now at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (fig. 14), this silhouette was produced around 1783–84 by her enslaver Jan Brandes, a Dutch Lutheran minister appointed to Batavia, the administrative headquarters of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in Southeast Asia. In the nine years he spent there, Brandes produced copious watercolors and drawings of daily life as well as renderings of animals, plants, and insects (fig. 15). He also made silhouettes of two women, Flora and Sara, and one child, Bietja, whom he purchased and held in bondage as domestic workers. Rather than cutting their profiles, Brandes traced the enslaved women’s projected images and then filled them in with broad strokes of black pigment; they are, like the Connecticut Flora’s silhouette, close to life size. Though produced in a distant locale, Brandes’s work suggests the widespread interest in silhouettes in the third quarter of the eighteenth century and the shared impulse to include enslaved people as subjects for such optical experiments.37

In Brandes’s case, silhouette making complemented his scientific pursuits. Because Brandes completed profiles of himself and his son as well as Flora, Sara, and Bietja, his practice suggests a comparative enterprise likely informed by the popular system of physiognomic analysis. For his 1783–85 profiles, Brandes might have consulted translations of Johann Casper Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy, published in Dutch from 1780 to 1783. Lavater was read internationally and contributed to the swelling popularity of silhouettes at the end of the eighteenth century. He promised that practitioners could discern temperament and intelligence through the study of head shape and facial features. His claims intersected with Enlightenment natural history to produce a racist science that many white silhouette patrons and makers embraced. Indeed, the Connecticut Flora’s profile also might have been shaped by Lavater’s physiognomic analysis, as Rosenthal and Lugo-Ortiz suggest.38

So too could the developing science of anthropometry—whose practitioners used measurements of facial angles and skull shape to make “scientific” arguments about racial difference—have played a role in spurring silhouettes made of people of African descent. This seems especially likely for Brandes, given his Dutch background and therefore possible knowledge of Dutch anatomist Petrus Camper’s 1770 demonstrations and published lectures, in which he used measured drawings of subjects in profile to argue that people of African descent had a different facial angle (from forehead to incisor teeth) than Asians and Europeans. Camper’s ideas, first published in English in 1794, together with Lavater’s essays and emerging techniques of phrenology, formed the bedrock of American racist anthropology that developed more fully in the nineteenth century. Even abolitionists deployed the popular sciences of phrenology and anthropometry, as in the 1840 silhouettes produced of the Amistad rebels and published in John Warner Barber’s A History of the Amistad Captives, in which the author assigned positive and negative behavioral characteristics based on skull measurements and shape. Black intellectuals, most notably James McCune Smith and Frederick Douglass, explicitly rejected phrenology as unscientific and racist.39

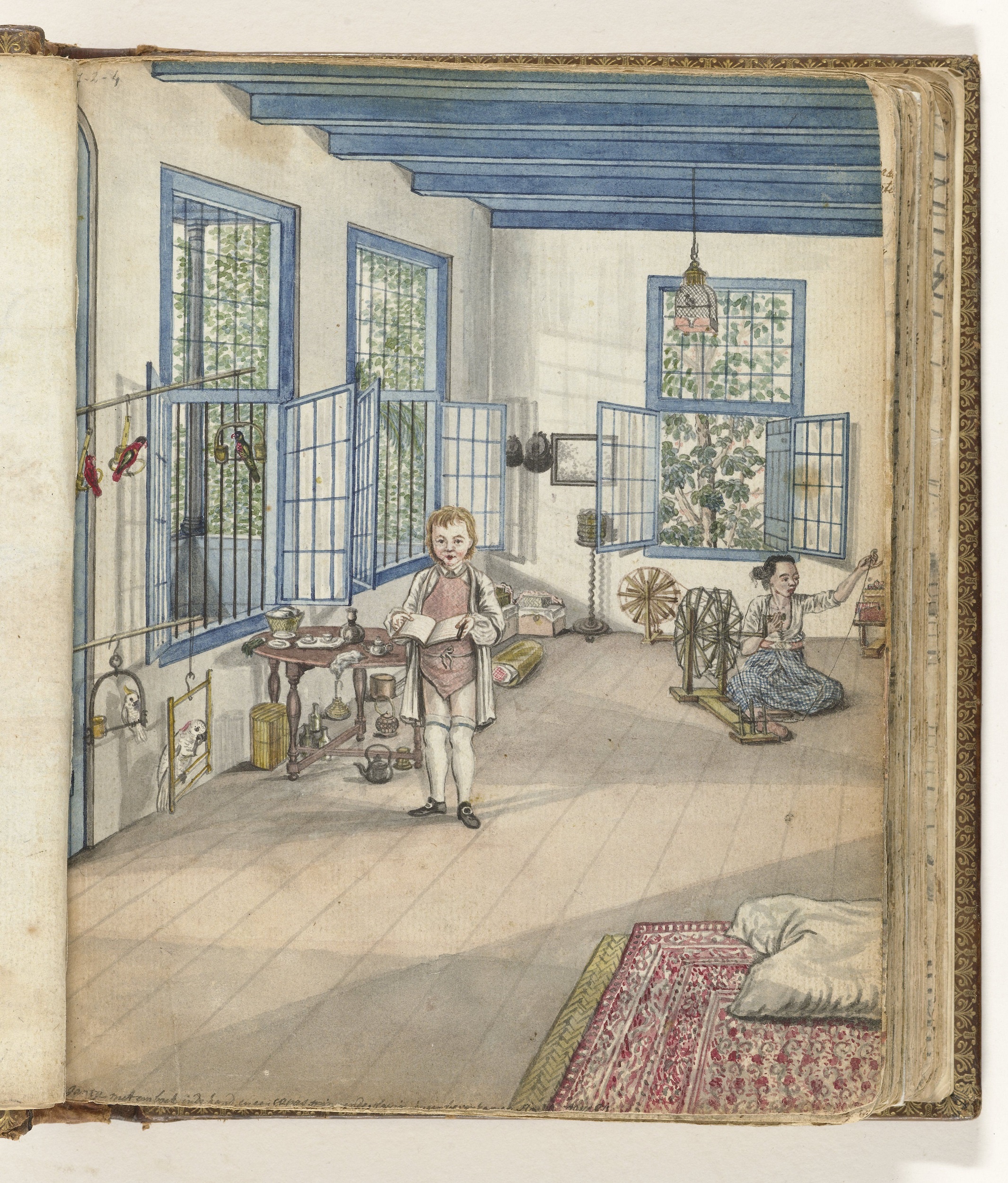

Brandes might have been intrigued by the racial identities of the women he enslaved and sought to categorize them using facial angles or to compare those angles to profiles of Europeans. Timang van Boegis—as Flora was first known before Brandes assigned her a new name—was likely kidnapped from the south Sulawesi region of Indonesia, her original name identifying her with this location. Like many people enslaved in Batavia, she was also perhaps partially of African descent. Brandes’s watercolor scenes suggest Flora’s complex racial identity as well as her labor within the household. In his precise rendering of a domestic interior (fig. 16), Brandes shows his son, Jan, standing in the foreground in Western dress, holding a book, while Flora, seated on the floor in the back right corner, spins cotton from Brandes’s plantation. The many exotic birds in the room formed part of his taxidermy collection, some of which Flora helped stuff as specimens of natural history. Like sitting for her silhouette, Flora’s labor in preparing birds for Brandes enmeshed her in an Enlightenment project as an unequal participant. Brandes’s watercolors of fauna and flora resonated with his silhouette of the enslaved and renamed woman, as they might all be read as specimens, subjects of the male possessor’s scientific gaze recorded in his sketchbook and brought back from the colony to the metropole. Indeed, since Brandes marketed tropical flowers from his plantation and also sold Flora in 1785 in anticipation of his departure from Batavia, the conflation of woman and flower was more sinister still.40

The silhouette and sketch of Flora/ Timang van Boegis encourage us to think of the Connecticut Flora’s profile in relation to other images made of enslaved domestic workers. Silhouettes of enslaved people constitute a tiny but significant portion of profiles taken in early America. For example, prominent silhouette artist Auguste Edouart cut approximately 3,800 silhouettes in the United States, seven of which he noted as being of enslaved individuals. A woman Edouart identified only as “Slave Belonging to Mrs. Oyley” sat for her full-length profile in New Orleans on March 1, 1844, at the same time as her white enslaver (fig. 17). The Oyleys likely paid for this image and kept it in their possession in an act that Fox-Amato, referring to 1850–60s daguerreotypes of enslaved sitters, describes as “intimate possession.”41 In this type of commissioning and ownership, the representational tropes of portraiture invoke the subjective humanity of enslaved people but only within the slaveholders’ circumscribed framework of meanings.

The Benjamins—or Flora’s previous enslavers, the Dwights—might have created Flora’s silhouette for their own visual consumption, as a marker of their ownership of her or as a record of their complicated emotional relationship with her, one predicated on inequality and an enslaver’s fantasy of subservience and devotion. To claim that the Benjamins might have wanted to have an image of Flora as a reminder of her is not to negate the possibility that she could have faced violence at their hands. In Batavia, Brandes’s treatment of Flora/ Timang van Boegis suggests the intertwining of brutality and enslavers’ emotional projections onto the people they enslaved. In October 1782, when Flora was recaptured after an escape, Brandes ordered two enslaved men to “beat her” and chain her up. Brandes reported that she had fled out of fear that he would discover her sexual relationship with an enslaved man named Valentijn. Brandes’s words suggest his assertion of sexual control over Flora and his own sexual exploitation of her. That possibility is strengthened by Brandes’s sexual relationship with Roosje, whom he also enslaved and sketched. He also ordered her beaten after she, too, fled over fear that Brandes would punish her for a supposed relationship with another enslaved man.42 Brandes’s actions suggest that the silhouettes that commemorated enslaved domestic workers and the violence he enacted against those same people were not contradictory but part of the same possessive logic of enslavement. Conditions of slavery were different in Batavia than in Connecticut, but we can easily imagine a similar scenario for Flora in Connecticut. Both Floras were vulnerable to violence, as North American enslavers also attempted to control and to limit enslaved people’s leisure, their friendships, and sometimes their sexual partners. And Flora was also potentially at risk for assault by the Benjamins’ rope walkers.43

If indeed the Benjamins made Flora’s silhouette, then the profile’s preservation and its eventual arrival in the Judson House might have occurred because of their psychic need to hold onto her memory as they had her body, even—or perhaps especially—long after her death. In 1797, one year after Flora’s sale to the Benjamins, Hannah’s sister Sarah Plant married Daniel Judson, grandson of Captain David Judson, who had commissioned the 1723 Judson House (see fig. 4). Sarah and Daniel Judson lived in downtown Stratford, merely two blocks from the Judson House, owned by Daniel’s first cousin Abner (II) and his heirs until 1881. It is possible that Flora’s silhouette and/or the bill of sale passed at some point into Sarah’s hands and then eventually into the Judson House nearby. The objects would have had to survive two major house renovations, first in the 1880s and again between 1891 and about 1926, just after the Stratford Historical Society acquired the house; their folding, however, suggests that either or both could have been tucked away for safekeeping. Alternately, Flora’s profile might have been preserved elsewhere within a Benjamin family house or collection and donated to the historical society only later, in the early decades of the society’s occupation of the Judson House.44

Either of these possible provenances might indicate the white families’ staging of their own family memories through the silhouette. Certainly the profile’s size, materials, and form indicate its creation and intended use within a familial or intimate setting, not for dissemination or publication. In this scenario, Flora’s profile, while not linked to her sale or potential recapture, would still have served as an object of “intimate possession.” At the very least, the possibility of a white maker in the context of slavery limits the scope through which we might interpret Flora’s profile as a fully subjective portrait.45

Part 3

But what if the artist were Black? Rather than an image made by or for her enslavers that inscribed her status as property, could this be an image that celebrated Flora’s humanity, made by someone close to her—possibly someone who was also enslaved? In 1800, eleven other enslaved African Americans plus thirty-one free people of color lived in households within the Benjamin family’s broader neighborhood.46 While our default assumptions, based on the relative power of enslavers, might make a Black maker seem less likely than a white one, there are good reasons to challenge this assumption.

At least one African American man became a professional silhouette maker in early America. Moses Williams, a mixed-race man enslaved by artist and museum operator Charles Willson Peale, used a physiognotrace to make hundreds of silhouettes for visitors to Peale’s Philadelphia Museum.47 More important, in the late eighteenth century, silhouette making was so popular and the vernacular practice was so widely known that virtually anyone with access to paper, a cutting implement, and glue or paste could have created Flora’s image. Indeed, the conjoining of the pieces of paper, the addition of a third scrap to complete the silhouette, and the unusual millboard backing indicate a nonprofessional and perhaps novice maker utilizing what supplies they could obtain. Even within the context of slavery, it was possible for African Americans to buy inexpensive wove paper and millboard from a stationer’s shop. The many transactions documented in shopkeepers’ ledgers of enslaved customers’ purchases of textiles, foodstuffs, and ceramics readily attest to this possibility.48 Or perhaps the materials were obtained surreptitiously from the white households in which enslaved people worked and stayed. Either way, the necessary cutting tools, usually embroidery scissors or a small knife, were easily at hand, especially for domestic workers responsible for household sewing and mending.49

The use of millboard in the silhouette also bears consideration in light of a possible enslaved maker. Composed of ropes and hemp, millboard is a coarse paper that is easier to make than white paper, which requires more skilled and lengthy processing. As a result, millboard was sometimes manufactured by millers expanding their enterprises into paper making temporarily or on a trial basis. Milford, as the name suggests, was an area dense with mills, beginning with Fowler’s grist mill, founded in 1640 on the lower Wepawaug River. While Milford had no paper mills until the late nineteenth century, at least two fulling mills—where wool cloth was finished—opened in this era, one on the Wepawaug in 1674 and the other on Beaver Brook in 1689; there were four in the area by 1815. Fulling mills could produce paper, as they already possessed the necessary equipment, and workers were familiar with the processing of materials required for paper production. It was not unusual for fulling millers to turn their hand informally to paper making. It is therefore possible that the millboard used in Flora’s silhouette was of local manufacture, purchased, bartered for, or taken from a Milford mill by an enslaved person or a white ropewalk worker. Benjamin’s ropewalk made his firm a likely supplier of hemp or rope to a nearby mill. As a seventeenth-century English observer noted, rough brown paper and millboard were made from “Coarse Raggs and useless Rope-Stuff serviceable only by that Occassion.”50 Perhaps then the rope employed in the millboard is even of Benjamin’s own manufacture—a piece of the finished product that made its way back to his household in an exchange or as a sample.

Enslaved Africans and African Americans found creative ways to express themselves visually, both through the normal course of their productive work and in their own time, using available materials, as for example in sewing and quilt making.51 We can readily imagine someone extending and applying their domestic work skills to profile cutting. Hand skills more often deployed in darning socks, finishing the hem of a piece of clothing, or even pinning a paper pattern to cloth before cutting the fabric could have been redeployed to cut a paper profile.52 There is no reason to assume, then, that Flora’s profile could not have been created by a Black maker.

To explore this possibility, we need to understand more about the African American communities in which Flora lived. In 1774, just before Flora’s birth, the 158 enslaved residents of Milford comprised 7.4 percent of the town’s total population of 2,127. In Stratford, similarly, 319 enslaved people comprised 5.7 percent of the 5,555 total. As in the rest of the colony, they tended to be held in a concentrated set of households: those of merchants, clergy, officials, and wealthy landholders. Africans and African Americans therefore comprised a quite visible minority, and they engaged in a robust private and public culture. Archaeological research has shown that these Black communities, even distributed among white households as they were, continued and adapted communal African spiritual practices, including burial rites. And theirs was a culture that moved across the coastal landscape: people of African descent gathered from miles away for annual holiday celebrations and parades. Most spectacular among these was “Negro Election Day,” when African Americans held paralegal governors’ elections, casting ballots for Black men typically celebrated for their strength, wisdom, and African heritage; these elected governors presided ceremonially over the Black community until the next election.53 So despite—and perhaps in part because of—their relatively small numbers, Africans and African Americans in coastal Connecticut carried a strong communal sense of identity, supporting each other across their dispersed domestic spaces.

Just as African-influenced culture persevered in spite of slavery’s violence, African Americans also formed families and communities within and across the constraints of white households. Therefore, to learn about Flora’s familial relationships, we need to understand those of her enslavers, especially Margaret DeWitt Dwight, who sold Flora to Benjamin in 1796. Flora was not the only enslaved person held by Margaret’s family; in 1790, there were five enslaved people in the household of her parents, Garrit and Margaret DeWitt. The census taker did not record names, ages, or genders, but Garrit DeWitt’s 1793 will named three: a man named Cudgehoe, a woman named Morea, and a woman named Monimian. The fourth person is not named and may have been deceased or sold by 1793. Separately, the 1794 estate of Garrit’s wife, Margaret, named a fifth individual: “my Negro Girl named Flora”—who was soon to have, or had recently had, her silhouette made. Flora was not the first Flora enslaved by Margaret’s family, however. One generation earlier, another Flora was held in bondage by the elder Margaret’s parents, New York City merchant Abraham Van Horn (no known relationship to coauthor) and his wife, Catharine. In his 1756 will, Abraham bequeathed to Catharine a woman named Flora. We have not been able to track what happened to this Flora—she was to be sold at Catharine’s death—but the fact that thirty-eight years later, in 1794, the Van Horns’ daughter Margaret Van Horn DeWitt’s estate included the younger Flora presents the strong possibility that the two Floras were related. Tellingly, Abraham Van Horn in 1756 also bequeathed to Catharine a man named Cudjo—possibly an older relative of the younger Cudgehoe in the 1793 DeWitt household. We are unable to determine whether the elder Flora or elder Cudjo ever made their way into the DeWitt household—and therefore whether young Flora grew up under their influence. Even if they did not, the intergenerational repetition of both names—Flora and Cudjo/ Cudgehoe—passed along by enslaved people bequeathed through the Van Horn family, suggests parental or other familial ties.54

It is worth noting that Cudgo is an Akan day name meaning “Monday,” signaling a sense of African as well as familial identity being passed down. Moreover, the pattern of name repetition resonates strongly with African American lineage and naming practices employed across British North America. On one North Carolina plantation, for example, historian Herbert Gutman found that children carried the name of a biological relative in 80 percent of cases. Half of these families had sons named for a father. And while naming daughters for mothers was less common, two-thirds of the families had at least one child named for an aunt or uncle. Perhaps the elder Flora was young Flora’s mother or aunt. If the elder Flora and Cudjo were spouses, then the younger Cudgehoe might have been Flora’s brother or cousin. While the linked names suggest a multigenerational African American family, members were likely dispersed among white households. In the immediate neighborhood of the DeWitt’s home, located on the Milford public green, there were twelve other enslaved people, four of them next door or very close by, plus twenty-six free people of color, most of whom lived in Black-headed households. Other members of Flora’s family, perhaps siblings or cousins, could be among those African Americans enumerated in the census.55

Given this knowledge, we might readily imagine Flora’s portrait as produced within a Black familial environment and for familial purposes. Just as the name Flora may have been passed down from one woman to another, the silhouette may have been produced in an act of remembrance that linked two generations by commemorating shared features. Those intentions would have been understood, at least implicitly, by the Van Horns and DeWitts, who similarly reused names to memorialize generational ties and who also deployed visual representations to maintain ancestral connections. Margaret’s mother, in passing down “my two Family pictures”—portraits of her parents—stipulated that if her son Garrit had no heirs, the paintings would go to William, and failing heirs there, to John instead. The elder Margaret sought to ensure that the pendant portraits, described as “large” and valued at six pounds, remained tied to her ancestral line. Perhaps Flora’s silhouette, too, was created by and for viewing and enjoyment but in this case Black rather than white, the smaller and more mobile silhouette, in a sense, running counter to the monumental oil-on-canvas portraits as a carrier of lineage.56

If a Black silhouette cutter produced Flora’s profile, it might help explain the sensitivity to Flora’s hair perceptible in the image. Because hair styles were often a means for eighteenth-century Africans and African Americans to express their creativity as well as cultural traditions, hair care remained a site for individual subjectivity despite enslavement. Flora’s silhouette strikingly traces the outline of her deliberately kept hair. Whether the raised triangles in profile represent braids, locks, or threaded knots, they signify her assertion of an identity distinctive from the white majority around her but also likely from her peers. They are an index of her subjectivity, as previous authors have argued.57

Indeed, Flora’s profile possibly represented not only an act of Black agency but perhaps, more specifically, one of Black female agency. The attentiveness to Flora’s hairstyle in the image could support this scenario. Hairstyling was often completed by people of the same sex in enslaved communities, giving a Black woman, perhaps more than a man, familiarity with Flora’s distinctive hair and an awareness of its personal importance and cultural meanings. A Black woman would also have been more likely to have ready access to fine scissors and a facility in sewing and handiwork needed to capture a profile view.58 The moment of styling Flora’s hair and of making Flora’s silhouette were points where Black female agency was probable. If this image were created by a Black woman, Flora’s profile might be the earliest known extant African American portrait by a maker of African descent and the first associated with a Black female artist. Of course, we cannot demonstrate conclusively that a Black woman cut Flora’s silhouette, nor do we want to argue for the profile’s status as “a first.” Rather than posit this silhouette as unique, our intention is to open a conversation about the potential for this and other early images to be the unacknowledged work of Black makers.59

We have traced the outlines of the Black community and potential family members who surrounded and supported Flora in Connecticut. New research on the DeWitts presents another intriguing possibility about Flora’s background and extends the number of candidates for making her silhouette; she might have spent several years in Virginia with Margaret DeWitt Dwight’s family before returning to Connecticut just before the sale. We know that Margaret herself had only just arrived back in Milford after several years away. Around 1789, she had married Dr. Maurice Dwight; they moved briefly to Baltimore, Maryland, and then settled in Kempsville, Virginia, a small port town on the Chesapeake, by December 1790, when their first child, Margaret, was born. They had a son, Henry, born 1793, and in October 1794, a daughter, Catharine, named for Margaret’s sister. The naming of Catharine seems significant since just seven months earlier, in February 1794, it was not Margaret but her sister Catharine who was named to receive Flora in their mother’s will. The fact that it was Margaret who then sold Flora in 1796, however, indicates that Catharine must have transferred Flora to Margaret sometime between the January 1795 division of their mother’s estate and the December 1796 bill of sale. Perhaps Catharine needed the money more than she needed the support of additional enslaved labor and felt that Flora’s labor might be more profitably employed in Margaret’s growing Virginia household. Indeed, Catharine was not yet married and probably lived with one of their brothers, Garrit or Abraham, in Milford. Margaret expressed affection for her sister in the naming of her own daughter after her, so the gift or sale of Flora to Margaret would not be implausible.60 And certainly it is difficult to imagine a doctor’s wife, in the pervasive slaveholder’s culture of Virginia, managing a household of several children with no female enslaved workers to support her.

The chronology of Margaret’s life and the sale of Flora also coincide to suggest this scenario. In 1796, a wave of tragedy washed over Margaret’s Virginia household. Her sixteen-month-old daughter, Catharine, died in February, just a month before the birth of her son Maurice. On August 11, she lost her husband to the yellow fever pandemic he was likely helping to treat, and ten days later, three-year-old Henry died as well. Margaret returned to Milford that fall with infant Maurice and six-year-old Margaret, the latter of whom she sent to live with Dr. Dwight’s mother.61 The sale of Flora, then, would seem to have been precipitated by this turn of personal and economic disaster for Margaret.

Moving Flora out of and then back into Connecticut might have raised legal questions, since the colony in 1774 had banned the importation of enslaved people, and the state in 1784 updated that law and enacted gradual emancipation. But the 1784 law only manumitted people born after March 1 of that year and, even then, only when they reached the age of twenty-five. Flora was already seven years old by then, and her sale within the state remained legal for the rest of her life. A 1792 law tried to curb out-of-state sale of those not covered by gradual emancipation, but it allowed exceptions for slaveholders carrying people out of state for purposes of residence. This would have been the case for Margaret, who may have taken Flora to Virginia by 1789 or 1790. Bringing Flora back into Connecticut in the fall of 1796 might have raised some eyebrows, however, especially since Margaret sold her almost immediately, in December. The import ban did, after all, apply to enslaved people brought in “to be disposed of, left or sold within” Connecticut and imposed a harsh penalty of one hundred pounds on both seller and knowing buyer.62 But if anyone had doubts, Margaret could simply have argued that she was merely bringing Flora back with her own family, and, in fact, she may not have even contemplated sale until after returning to Milford and discussing matters with her brothers. There was, then, no legal impediment to carrying Flora to Virginia and back again, and the timing of Margaret’s return and sale of Flora points to this forced migration as a strong possibility.

If Flora accompanied the Dwights on their Virginia sojourn, she might have left Connecticut around age twelve or thirteen, only to return to be sold in 1796 at the age of nineteen. As she would later at the Benjamin household, Flora likely helped to care for the Dwights’ children and to perform household labor. However, during her teenage years in Virginia, she would have come into contact with a different group of enslaved people and encountered a different cultural environment than the one in which she had grown up in Connecticut. With a population 41 percent enslaved, tidewater Princess Anne County would have immersed Flora in a much broader and more diverse African American culture, perhaps multiplying the opportunities for her to engage a friend to cut her silhouette and to help fashion her hair into its distinctive style. Domestic architecture in the Chesapeake even encouraged this cultural distancing. Kitchens and other work spaces in Virginia were often housed in separate outbuildings, where many African Americans labored and also slept beyond the main house and thus outside enslavers’ immediate purview. Kempsville had been an important colonial Virginia port and was bustling in the 1790s. But it remained a small town in a rural landscape characterized by wetlands, woods, and plantation fields. This porous landscape may have provided Flora with more opportunities to claim her own time among African Americans, both during the workday and in the evenings, increasing her possible freedom to sit for an image.63

Part 4

With Flora’s specific familial contexts in mind, we turn now to the spaces in which her profile may have been made and displayed. Separate slave quarters were rare in New England, with enslaved people sleeping in haylofts and sheds, on landings and hearths. We do not know where Africans or African Americans stayed in the Van Horn, DeWitt, Dwight, and Benjamin households—none of these houses are standing, to our knowledge. However, the Judson House (see fig. 4), where Flora’s silhouette was recovered in the twentieth century, provides a viable reference. Indeed, just before Flora’s birth, in the early 1770s, five enslaved people—Jim, Rose, Titus, Ames, and Peg—stayed there, held by Captain David Judson’s son Abner. While the Stratford Historical Society has emphasized the basement kitchen as a site of enslaved labor (see figs. 5 and 18), the Judson House actually includes two kitchen hearths, with an “upper” kitchen in the large back room on the ground floor. This ground-floor kitchen was, in fact, a more common local architectural feature (fig. 19). In the region’s most ubiquitous early house type for those with means, known as the “saltbox,” a large ground-floor kitchen hearth dominated a rear room, often spanning the width of the house (sometimes divided into smaller rooms), served by a large central chimney. This hearth—typically seven to nine feet wide and up to four and a half feet tall—was originally inside a “lean-to” room tacked onto the rear of the gabled house, giving the house its namesake form. By the early eighteenth century, this room was designed as part of the house, and even houses built as full two stories, including the Judson House, included this large rear kitchen hearth on the ground floor. The saltbox form would seem a likely candidate for the home of the Van Horns, where the elder Flora and Cudjo were enslaved, and for the DeWitt house on the town green in Milford, where Flora was enslaved before the sale. Asa Benjamin’s house in Stratford, as depicted on the Barnum map, shows two internal chimneys and a window arrangement indicating a central passage plan that placed the kitchen in one of the rear corner rooms but still on the ground floor, as with the lean-to plans.64

In all these cases, the spaces of enslaved labor were somewhat integrated into the white household and therefore more open to scrutiny and oversight than the Judson House cellar space. Still, we might imagine enslaved women left to their work, spending hours chopping, boiling, baking, and roasting food over these hearths as well as processing textiles, mending, or sewing by the fire’s light (figs. 18 and 19). These spaces, obviously the sites of sweat and tedium, were also zones where African Americans exercised what spatial control they could and where creative activities could take place. Recent archaeological investigations of colonial Connecticut houses and other buildings indicate that enslaved African and African American residents literally demarcated the cellar, garret, and other service spaces they occupied, inscribing signs and carving figures on joists, beams, and floorboards, even leaving behind crafted objects with likely spiritual meaning and power.65

The firelight cast by the kitchen fireplaces that dominated the workspaces where enslaved women cooked, worked, ate, and slept was ubiquitous. How many times might Flora have watched her shadow flicker across a stone or plastered kitchen wall? Seated before a fireplace in Milford or Stratford, Connecticut—or even in a kitchen separated from the main house, more typical for Kempsville, Virginia—an enslaved woman perhaps traced Flora’s silhouette on paper carefully salvaged or purchased, then used the embroidery scissors typically employed for mending and darning enslavers’ clothing to cut the silhouette, and finally pasted it in place on a purchased or taken piece of millboard. It is fitting, then, that the Stratford Historical Society long displayed Flora’s silhouette in this cellar kitchen. We cannot connect Flora herself to the Judson House, but its two kitchen spaces are suggestive of the environments in which Flora worked and lived as well as the possible setting for the creation and perhaps original display and preservation of her portrait.66

Considering a Black maker introduces the possibility of Black viewership and possession of Flora’s silhouette. Remember that Flora shared the DeWitt’s household in Milford with Monimian, Morea, the younger Cudgehoe, and one other enslaved African American, possibly the elder Flora. Four other enslaved African Americans stayed a few doors down; eight others were nearby; and twenty-six free people of color lived in the neighborhood as well. Even though we cannot know much about them, these individuals’ presence enables us to imagine an enslaved community that surrounded and likely supported Flora. Her silhouette, folded into a bundle, might have been initially preserved through networks of friendships that sustained enslaved people in the interlinking Black communities of Milford and Stratford. Records show that by 1790 and thereafter, there do not appear to have been any people held in slavery at the Judson House, making a direct conduit there by an African American possessor unlikely. But we can well imagine the silhouette being preserved by Flora’s family in the DeWitt household—perhaps commemorating her absence in Virginia—or, later, held by Flora herself at the Benjamin household, whether privately or with full knowledge of the Benjamins. Historian Stephanie Camp documents two cases of enslaved people asserting aesthetic choices with visual artifacts in their domestic spaces, even in the face of their enslavers’ opposition (in these cases, a display of antislavery “prints” and a newspaper image of Abraham Lincoln).67 If the Benjamins confiscated the silhouette during Flora’s lifetime or discovered it after her death, they or their descendants might eventually have paired it with the bill of sale, which would have been part of Benjamin’s business records.

If Flora’s profile remained in the hands of a Black user or users for some time, then it is also a product of a Black family and community who chose to keep it safe. Jan Brandes’s silhouettes provide a useful counterpoint. His images of Sara and Bietje (figs. 20 and 21), when placed alongside his profile of Flora/ Timang van Boegis (see fig. 14), offer an unintentional archive of an enslaved female community: two women and a girl who served in bondage together as household staff but who surely formed emotional bonds among themselves. Their commonality of experience as well as engagement in cooperative tasks like childminding—this Flora, for instance, gave birth in 1782 (there is no similar indication for Flora in Connecticut)—likely united these women in bondage. Their relationships, no doubt contentious as well as supportive, defined the contours of their emotional lives.68 We can imagine the meanings that Sara’s and Bietje’s profiles might have held for Flora after the three were separated on Brandes’s departure, for instance, though, of course, Brandes took those images with him, denying that tactile connection. Back in Connecticut, the preservation and descent of Flora’s silhouette might indicate that someone enslaved in Milford or Stratford held onto her image and used it to recall the absent Flora before it passed into the space of the Captain Judson House.

Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw eloquently describes how, “in its organic regularity,” Flora’s hair “becomes like the petals of a flower. . . . Her image, like a pressed blossom, is sandwiched into the two dimensions of the paper.”69 The silhouette’s mounting on millboard, commonly used for book covers, and the fact that it was at some point folded so that it resembled a small but thick book or scrapbook also resonates with this invocation of the pressed keepsake. The implied folding and unfolding of the silhouette by viewers over time suggests the image’s potential to spur memories bound up not with property value but with affection and familiarity.

Flora’s portrait, if produced by and for a Black user, could never be a “slave portrait.” In that case, the maker and preserver saw Flora as person rather than Flora as possession. To them her subjectivity was never in doubt. Of course that attribution is not a demonstrable fact but rather a potential, or set of potentials. To offer agency in place of dishumanization70 is a scholarly choice that embraces conjecture and allows for a nonconclusive series of possibilities. Saidiya Hartman and others remind us of the benefits of practicing informed speculation to more fully tell enslaved people’s visual and material histories.71

Flora’s silhouette reveals that American art history has yet to fully come to terms with the fact that racialized disenfranchisement within a system of slavery makes evidence difficult to come by and conjecture a necessity. To practice art history in a racially inclusive way, we must let go of default assumptions of white makers, take seriously the project of locating Black makers, and be willing to let multiple possibilities coexist. Scholars accepting the received origin story of Flora’s silhouette—like those interpreting the Zealy daguerreotypes of Delia, Renty, Drana, Jack, Alfred, Fassena, and Jem—have worked to recover Flora’s subjective humanity from an image assumed to objectify her, reading it against the grain.72 By disentangling Flora’s profile from the bill of sale, we would like to read with the grain, seeing in the silhouette’s original creation and preservation the possibility of Black self-expression—for both artist and sitter. Before photography, silhouettes were thought by many to be the most accurate form of representation, creating, as they did, a literal trace of the person’s physical presence. By taking cues from the portrait itself and from its historical context, we would like to open interpretive possibilities, to work to see in it some trace of Flora herself.

June 17, 2022: An earlier version of this article swapped the captions for figures 20 and 21.

July 9, 2022: The full name of the Greenberg Steinhauser Forum in American Art was added to the acknowledgments.

Cite this article: Phillip Troutman and Jennifer Van Horn, “Seeing Flora’s Profile as Portrait,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.13111.

PDF: Troutman and Van Horn, Seeing Flora’s Profile

Notes

The authors are especially grateful for the generosity of Robyn Asleson, Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, who shared her ongoing research into the profile’s provenance, and to Im Chan, paper conservator for the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery, who shared her knowledge of the material objects gained during the conservation process. We accept responsibility for any errors in fact or interpretation. We would also like to thank Allegra di Bonaventur for opening up a new line of research for us, Wendy Bellion for her thoughtful comments on an early draft, and Stratford Historical Society staff for sharing their knowledge. Finally, thank you to Asma Naeem, who invited us to the Greenberg Steinhauser Forum in American Art study day for the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition Black Out, which spurred our initial conversation about Flora.

- Asma Naeem, Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now (Princeton: Princeton University Press in association with National Portrait Gallery Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC, 2018), 92–93; National Portrait Gallery, “Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now,” May 11, 2018–March 17, 2019, https://npg.si.edu/exhibition/black-out-silhouettes-then-and-now; Philip Kendicott, “Before Photography, the Silhouette Helped Leave an Impression,” Washington Post, May 21, 2018. For the logic of pendants, see Wendy N. E. Ikemoto, Antebellum American Pendant Paintings: New Ways of Looking (New York: Routledge, 2018). ↵

- Agnes Lugo-Ortiz and Angela Rosenthal, “Introduction: Envisioning Slave Portraiture,” in Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 22. For the common assumption that the silhouette was made on the occasion of the sale and accompanied it, see “Flora,” PBS, Africans in America, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h69.html. ↵

- This essay thus counters Naeem’s claim that “the silhouettes of . . . enslaved individuals . . . such as Flora . . . are more vessels of transient information that expose subjugation than they are portraits”; Black Out, 28. Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw offers the most thorough analysis of Flora’s silhouette before the Black Out exhibition and catalogue. We indicate our intersection with and divergence from her arguments at different points in the essay; see Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century (Seattle: University of Washington Press for the Addison Gallery of American Art, 2006), 49. We are indebted to a rich body of scholarship on silhouettes, especially Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, “‘Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles’: Silhouettes and African American Identity in the Early Republic,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 149, no. 1 (March 2005): 22–39; Anne Verplanck, “The Silhouette and Quaker Identity in Early National Philadelphia,” Winterthur Portfolio 43, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 41–78; and Wendy Bellion, “Heads of State: Profiles and Politics in Jeffersonian America,” in New Media, 1740–1915, ed. Lisa Gitelman and Geoffrey P. Pingree (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 31–59. ↵

- Marcia Pointon, “Slavery and the Possibilities of Portraiture,” in Rosenthal and Lugo-Ortiz, Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World, 42. ↵

- David Bindman, “Subjectivity and Slavery in Portraiture: From Courtly to Commercial Societies,” in Rosenthal and Lugo-Ortiz, Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World, 75. ↵

- John Michael Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990); John Michael Vlach, By the Work of Their Hands: Studies in Afro-American Folklife (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991); Aaron De Groft, “Eloquent Vessels / Poetics of Power: The Heroic Stoneware of ‘Dave the Potter,’” Winterthur Portfolio 33, no. 4 (1998): 249–60; Michael A. Chaney, ed., Where Is All My Relation?: The Poetics of Dave the Potter (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018); Regenia Perry, Harriet Powers Bible Quilts (New York: Rizzoli International, 1994); Black Craftspeople Digital Archive, https://blackcraftspeople.org; Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA Journal) 41 (2020), https://www.mesdajournal.org. We look forward to the publication of Tiffany Momon and Torren Gatson’s coedited volume Black Craftspeople on the Southern Landscape, 1650–1865. On the broader visual field, see Grey Gundaker, Signs of Diaspora / Diaspora of Signs: Literacies, Creolization, and Vernacular Practice in African America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998). ↵

- We are indebted to the art historians, curators, and collectors who have worked to recover early Black North American artists, a process that continues today. See especially James A. Porter, Modern Negro Art (1943, repr. with new introduction by David C. Driskell, Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1992); James A. Porter, Ten Afro-American Artists of the Nineteenth Century: An Exhibition Commemorating the Centennial of Howard University, February 3–March 30, 1967 (Washington, DC: The Gallery of Art, Howard University, 1967); David C. Driskell, with catalogue notes by Leonard Simon, Two Centuries of Black American Art (New York: Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Alfred A. Knopf, 1976); Dorothy B. Porter Wesley, “Patrick Henry Reason (1816–1898),” in Dictionary of American Negro Biography, edited by Rayford W. Logan and Michael R. Winston (New York: W. W. Norton, 1982), 517–19; Steven Loring Jones, “A Keen Sense of the Artistic: African American Material Culture in Nineteenth Century Philadelphia,” International Review of African American Art 12, no. 2 (1995): 4–29; and Lisa Farrington, African-American Art: A Visual and Cultural History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017). ↵

- Scholars are still bringing stories of Connecticut slavery and African American life to light. See Kari J. Winter, “Slaves Under the Driveway? Exhuming Buried History in Milford and Southbury, Connecticut,” Connecticut Review 30, no. 2 (2008): 63–72; Robert P. Forbes, “Grating the Nutmeg: Slavery and Racism in Connecticut from the Colonial Era to the Civil War,” Connecticut History 52, no. 2 (2013): 170–201; and Vincent J. Rosivach, “The Hubbards, an African-American Family in Connecticut, 1769–1810,” Connecticut History 35, no. 2 (1994): 263–77. Modern scholarship on slavery and Black life in colonial New England began with African American historian Lorenzo Greene’s The Negro in Colonial New England (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942). See also William Piersen, Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988); Wendy Warren, New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America (New York: Liverright, 2016); Jared Ross Hardesty, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England (New York: Bright Leaf Press, 2019); and Joan Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England (New York: Cornell University Press, 2000). ↵

- Guocun Yang, “From Slavery to Emancipation: The African Americans of Connecticut, 1650s–1820s” (PhD diss., University of Connecticut, 1999), 112–27, 132. ↵

- David Menschel, “Abolition Without Deliverance: The Law of Connecticut Slavery 1784–1848,” Yale Law Journal 111, no. 1 (September 2001): 185, 191. See also Melish, Disowning Slavery. ↵

- We are inspired by Cheryl Finley’s discussion of the slave ship abolitionist print as icon; Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018). See the covers of Rosenthal and Lugo-Ortiz, Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World, and Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia, paperback ed. (1975; repr. New York: W. W. Norton, 1995). The ubiquity of Flora’s profile was also furthered by the silhouette’s frequent display and appearance in traveling exhibitions. The May 1995 Stratford Historical Society newsletter gives a sense of the silhouette’s frequent use and exhibition, announcing: “FLORA’S FAME keeps spreading. In the Sammis store display case in our museum which is located directly below the 1796 silhouette of Flora, the slave, are shown four books in which Flora has been featured. This extremely rare portrait and its accompanying bill of sale are widely known. ‘Flora’ has been prominent in exhibitions in Washington, D.C., and Brooklyn. Recently she has been requested for a traveling exhibition that would take her to Hartford, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Ohio, New Jersey, and New York State. The Executive Board must act on this request”; Stratford Historical Society newsletter, May 1995, http://stratfordhistoricalsociety.info. ↵

- Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019), xiv–xv. See also Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 1–14. ↵

- One account states that “Sometime prior to 1921, a silhouette was found in a drawer in the slave quarters {cellar kitchen} of the Judson House. The silhouette had an accompanying bill of sale dated 1796 for a slave woman named ‘Flora.’” Others have said it was found hidden in a wall of the cellar kitchen. Stratford Historical Society staff have also suggested that it was possibly donated to the society after 1925, having been found “folded up in the lower levels of a house”—not necessarily the Judson House. Contrast “Miss Flora Goes to Washington,” Stratford Historical Society Update, March 2018, with Melvin Mason, ‘From Stratford to the Smithsonian,” Stratford Star, June 28, 2018, both at http://stratfordhistoricalsociety.info. Phone conversations with Stratford Historical Society staff, May 2019 and January 2022. ↵