Bernard L. Herman

We welcome your responses and reminiscences in the Comments section below.

On September 13, 2025, hundreds of people gathered on the Eastern Shore of Virginia to remember the remarkable life of Bernard L. Herman, donning pins emblazoned with one of his mottos, “Stay Strange But Don’t Stay a Stranger.”1 Bernie was deeply interdisciplinary in all senses of the word: a folklorist by training, art collector and museum curator, oyster farmer, fig tree tender, loving father and husband—and his memorial celebration brought together people from all walks of life who loved him, including large numbers of former students like myself who ranged from knowing him for decades to only encountering him more recently. I fall toward the latter end of that spectrum, but one thing that struck me was how I recognized my own experiences in so many of the stories shared by people who knew him much longer, and I was not alone in that. When many of us laughed at the same parts throughout the ceremony, I could hear how we “Hermanites”—as one person called us—have all been imprinted with the seriousness, humor, and mindboggling qualities that characterized Bernie.

I started getting to know Bernie in 2010, when I began my PhD in Duke’s Art, Art History and Visual Studies department. My program also permitted me to take classes at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill—which has both an excellent Art History Department with more Americanists than Duke as well as a renowned American Studies department, which Bernie chaired for many years—so I found myself en route to UNC regularly on the Robertson Scholars bus. Bernie had only recently arrived there after a distinguished career at the University of Delaware, where he was most celebrated as an architectural historian. He was, for instance, a three-time winner of the Abbott Lowell Cummings Award given by the Vernacular Architecture Forum (VAF), which, as one of his former students noted, a person is lucky to get once in their career. The VAF also awarded Bernie the Henry R. Glassie award earlier this year—a particularly meaningful gesture given that Glassie’s Patterns in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States (1969) had inspired Bernie to apply for his PhD in the Folklore and Folklife program at University of Pennsylvania in the first place.

Bernie’s arrival in North Carolina in 2009 heralded a new chapter of his career, in which he began working more on the art of living self-taught artists—rogue geniuses whom the academy has never quite known how to handle. Many professors, curators, and museum directors of Bernie’s generation had found themselves baffled by the polarizing personality of Atlanta-based collector Willliam S. “Bill” Arnett, who had been beating the drum for artists across the South since the 1990s, creating an indispensable record of their lives and work in a two-volume publication, Souls Grown Deep. Bernie first became acquainted with Bill in advance of Gee’s Bend: The Architecture of the Quilt—a highly underrated 2006 exhibition accompanied by a catalogue with significant essays by quilters like Mary Lee Bendolph and her daughter-in-law Louisiana. Bernie used his essay, which brought together his eagle eye for architectural lexicons and his ease with quilters (his wife Rebecca is one) to platform the voices of many other Gee’s Bend women. When he died last December, Bernie was working on multiple manuscripts, including Quilt Spaces, a project based on the extensive interviews that he conducted with thirty Gee’s Bend quilters—interviews that uniquely brought forward “how the artists speak to the work that quilts do within their own creative imaginations.”2 Having become more entrenched in histories of Black quilters in recent years, I can say that Bernie’s approach of centering the voices of these women has been extremely rare and will be a tremendous resource for the next generation of scholars who seek to cut the Gordian knot of whether the art world should consider quilts as Art with a capital A and let the artists speak for themselves about the aesthetic intentions they carried into their textile production. I can’t wait to read them.

A folklorist by training, Bernie was incredibly people-centered, including in his approach to teaching. One of my greatest takeaways from learning with Bernie was the delight he took in his students, especially when we found original ways to make critical gestures. I remember that one student in a seminar he was teaching on self-taught artists took all of the artist profiles off of a blue-chip Outsider Art gallery’s website and redacted all biographical information, as a way of proving how little was said about their actual art. This supported Bernie’s ideas about the “connoisseurship of dysfunction,” a concept that skewers one of the obstacles in the reception of self-taught artists: an overemphasis—sometimes to the point of fetishization—of the various states of disability, poverty, or mental illness that so often marginalize them.3 Bernie had talent for using the poetics of conceptual language to make his points particularly memorable and incisive and loved to subvert art historical discourse with surprising uses of its own paradigms. To Bernie, the artist Thornton Dial—who grappled with everything from the death of Princess Diana, to the wreckage left in the wake of a sunken slave ship, to the children who perished in a World Trade Center daycare during 9/11 in his muscular, large-scale painted assemblages—was clearly a history painter who belonged at the top of the hierarchy of painting once blessed by royal academies. Further, Bernie framed the community of artists that Dial flourished within for decades beginning in the late 1980s as the “Birmingham Bessemer School,” a way of underscoring that defining artistic milieus can indeed emerge in places as seemingly barren as the economically depressed and racially terrorized Southern Rust Belt.

And yet, even as Bernie was eager to show how self-taught artists could be framed by the same paradigms on which art historians have relied to establish hierarchies or norms of intellectual sophistication and exchange, he was deeply distrustful of the politics of annexation he saw happening when previously marginalized artists were deemed canonical. It is hard to imagine a more victorious moment for self-taught artists than when the Metropolitan Museum of Art erected a giant banner reproducing a Dial work, History Refused to Die (2004), to announce the 2014 exhibition of their gift from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation. But Bernie did not leave the world thinking that the work was done; instead he left it with an exhibition and book, Unsettled Things: Art from an African American South—and more on that soon. Bernie was intellectually restless and anarchic in this way, bristling at definitive pronouncements and skeptical of simple solutions to entrenched problems. Many have noted in their remembrances of him how he seemed to be more interested in the questions than the answers. I remember going to his office hours in the research phase of my dissertation, overprepared like the good Virgo that I am with a new prospectus draft or chapter notes in hand. I had lists! But he had riddles that sent my brain through never ending loops as I rode the bus home and tried to unpack what had just happened. As his close friend Tom Ryan put it at the memorial, at times Bernie was “impenetrable. He was speaking from the realms which he inhabited in his own mind.” That Bernie’s mischievous grin and signature spectacles made him look a bit to me like the Cheshire Cat left me feeling in turn like Alice, a pupil whose practice and polish were of little use after falling deep into the rabbit’s hole.

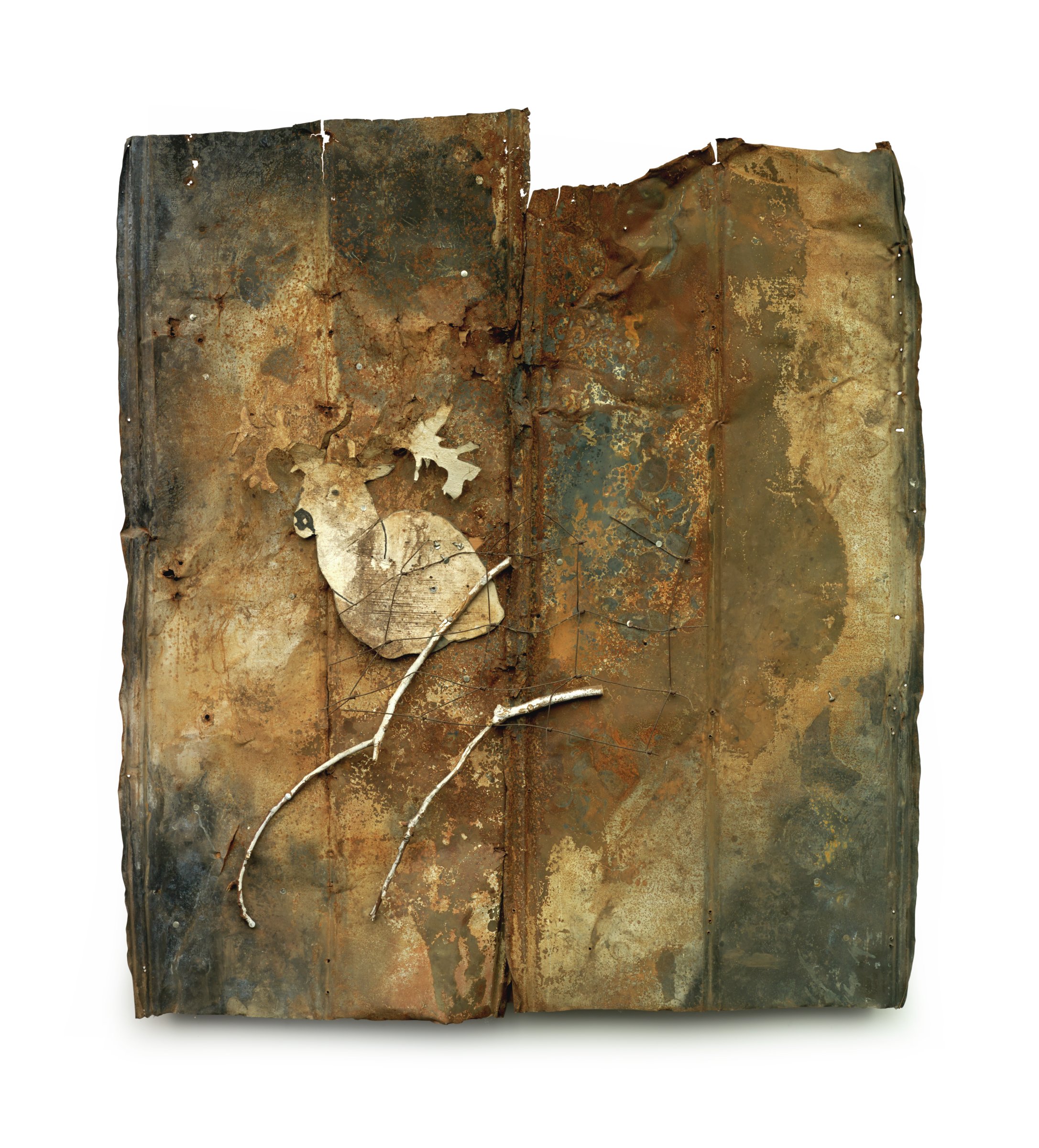

Another way to think about these provocations is that they were sincere invitations to collaborate. He enjoyed co-authoring and writing in nontraditional formats—as in an essay he co-wrote with his frequent interlocutor, Colin Rhodes, for the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Great and Mighty Things: Outsider Art From the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection (2013) that was conceived as an epistolary exchange. As an editor of catalogues myself now, I can only imagine trying to wrangle that contribution, but it’s a wonderful antidote to the often stale catalogue essay format. Bernie also became a curator in his own right over the last decade and a half of his career, organizing three exhibitions for UNC’s Ackland Art Museum on Souls Grown Deep artists, including Dial, Ronald Lockett; and the aforementioned group exhibition that drew widely on the museum’s permanent collection, Unsettled Things. When he curated exhibitions, he always made space for his students to contribute essays, giving us not only a chance to think deeply about the art we cared about, but also a c.v. boost that is so critical to emerging scholars. He did this for me when he organized Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett, a nationally touring exhibition that wound up being the first major loan show I brought to the High Museum of Art in 2016. As fate twisted on, the High also acquired the profoundly disarming metal assemblage featured on the catalogue’s cover, Once Something Has Lived It Can Never Really Die (fig. 1). The title of Lockett’s heartbreaking masterwork embodies—if ever anything did—the poetics so loved by Bernie. It also dwells in the duality of loss and legacy in which those of us who mourn and celebrate Bernie find ourselves today.

Bernie passed at the tail end of December of 2024, not long after Unsettled Things went on view at the International African American Museum, a new institution built on the site of Gadsden’s Wharf, one of the most active ports of the transatlantic slave trade. Earlier this year, I had a narrow window to see the exhibition on my way back from Wilmington, North Carolina, where I was doing research for my current exhibition on Minnie Evans, whose ancestors came through that port. Charleston was by no means on my way home to Atlanta, but I thought I could swing it, even if it would mean spending ten hours in the car that day instead of six. My window to arrive at the museum before closing time began to slip shut, however, as I waited on one of the elders of the Evans family to confirm a time for us to meet. Mr. Norris Evans—Minnie’s last surviving grandchild—did call, and the beautiful morning we spent together turned out to be especially fated, as he too would leave this world just a few months later, passing in July of 2025. By the time I left the Evans residence, I had no chance of seeing Unsettled Things before closing, but I know Bernie, inexhaustible conversationalist and cherisher of human lives that he was, would have blessed that choice.

- Since Bernie’s passing, a number of wonderful tributes to him have been published on the sites of his former academic departments and professional associations as well. See “–Henry Glassie Award: 2025 Bernard L. Herman,” Vernacular Architecture Forum, accessed September 24, 2025, https://www.vafweb.org/Glassie-award; “In Memoriam: Bernard L. Herman,” UDaily, January 17, 2025, https://www.udel.edu/udaily/2025/january/in-memoriam-bernard-herman; and Jessica Abel, “Carolina Community Remembers Bernie Herman,” College of Arts and Sciences, February 27, 2025, https://college.unc.edu/2025/02/herman. ↵

- “Bernard Herman, North Carolina: Meet the Collector Series Part Sixty Two,” Jennifer Lauren Gallery, accessed September 24, 2025, https://www.jenniferlaurengallery.com/news-press-media/bernie-herman-interview. ↵

- am sure Bernie published on this idea in one of his essays or articles that eludes me, but he spoke frequently about it both in his seminars and public lectures, especially around 2011. ↵