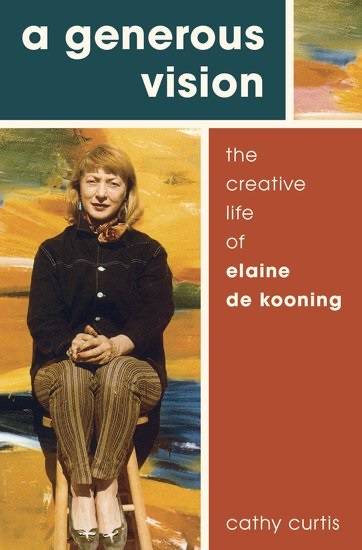

A Generous Vision: The Creative Life of Elaine de Kooning

Cathy Curtis

New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. 304 pp.; 31 color illus.; 27 b/w illus.; Hardcover: $25.49 (ISBN: 9780190498474)

New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. 304 pp.; 31 color illus.; 27 b/w illus.; Hardcover: $25.49 (ISBN: 9780190498474)

Cathy Curtis’s book, A Generous Vision: The Creative Life of Elaine de Kooning, published as part of the Oxford Cultural Biographies series, is the first biography of this painter and art critic. As we find out at the very beginning, despite “painstaking research and dozens of interviews,” the structure of the text was determined by lost memoir notes, mislaid diaries, scattered correspondence, the fluidity of memory, and the unreliability of anecdotes. The elusive nature and seeming inconsequentiality of the archival record precluded the possibility of realizing a classic biographical narrative. The author explains that this is the reason for the narrative being organized thematically, and not chronologically, which results in the occasional overlapping of stories, as well as an unequal amount of attention paid to individual segments. In the ten chapters making up this book on Elaine de Kooning, we find out about her early years and artistic development, pedagogical work, pronounced unconventionality in mid-twentieth-century America, dedication to her family and friends, and marriage to Willem de Kooning. The book is a complex story about various social, artistic, and psychological discourses being privileged and sometimes problematically underprivileged. We also learn about the distribution of power in the art world, about the framework of gender and otherness, and about artists and the institutions that support them. This biography of de Kooning therefore emerges as a generous vision not only of a tumultuous and creative life, but of an entire epoch.

The first chapter, “Drawing and Discovering,” describes de Kooning’s early family life dominated by her difficult and unstable mother, Marie O’Brien Fried, whose autocratic character and unconventional behavior were stoically accepted by her family. Their joint visits to museums and libraries and her mother’s artistic and literary advice, as well as her mental health problems, shaped de Kooning’s life in a complex manner, with traces of this legacy appearing in subsequent chapters. Although Curtis reiterates that de Kooning’s independent spirit needed “nothing but Mother and Bill” (1), the chapter also focuses on how Elaine de Kooning was equally shaped by growing up in Brooklyn, wandering through Manhattan (where she was allowed to take the subway on her own from the age of nine), and her mother’s pride in being a New Yorker. The city became the obligatory scenography of de Kooning’s life, the starting and permanent point of her professional strongholds.

On the trail of the importance of the city to de Kooning, the second chapter, “Life with Bill,” could just as easily be changed to “Life with the New York Art Scene.” The numerous addresses where Curtis takes us create an imaginary map of “Elaine de Kooning’s New York,” equated with the topoi of “art New York.” This imagined map provides ample testimony of de Kooning’s continual mobility and serves to indicate the struggle of the aspiring young artist to ensure the continuity of her artwork, even under difficult material circumstances. It also reveals a life without social etiquette and conventions, unfolding in between studios and cafés, clubs and galleries. Descriptions of de Kooning’s exhibitions and art sales are intertwined with everyday existential uncertainties. The manner in which the book presents picturesque anecdotes of this epoch, introduces the interests and lives of other contemporaneous artists, and includes very straightforward analyses of de Kooning’s paintings expands the potential readership of this book beyond the narrow circle of professional art historians.

The postwar New York art scene and protagonists who created it are successfully sketched out through descriptions of the de Koonings having a good time, of them entertaining company and enjoying parties, of the literature they were reading, of “Bill’s habit of whistling themes from classical music, which got on Elaine’s nerves” (29), and numerous other unpretentious notes and anecdotes. Of particular importance are the details of de Koonings’ living conditions, which determined the possibilities of Elaine de Kooning’s creativity. While seemingly banal, notes on buying canvas and thoughts about how much color it would take to fill it subtly problematize the causal relations between opportunities and desire, the starting point and its realization, compromise, and determination.

The third chapter, “Black Mountain, Provincetown, and the Woman Paintings,” focuses, in part, on Willem de Kooning’s engagement at Black Mountain College, an episode that Elaine de Kooning viewed “as the college experience she had missed out on” (43). In a bricolage of bohemian life—including dancing lessons held in the college dining room with Merce Cunningham, lectures spanning topics from Tolstoy to industrial design, Erik Satie’s concerts for the piano played by John Cage, the production of The Ruse of Medusa (in which Elaine de Kooning played the role of Frisette), modest food, and even more modest accommodations—one gains authentic insight into the everyday life of this indispensable, mythical place of modern American art. During her stay at Black Mountain College, de Kooning established lifelong connections with individuals in the worlds of avant-garde theater, dance, and poetry; these protagonists subsequently appear in her canvases, illustrating the art spaces in which she moved.

The chapter “Illuminating Art,” sums up Elaine de Kooning’s critical work for ARTnews, starting in 1948. The unswerving dedication with which she approached this dimension of her career confirms her passionate immersion in the world of art.

The disjointed nature of chapter five, “East Hampton, Pro Sports, and the Separation,” elucidates the warning early in the book about its structure being conditioned by the amplitude of source material (or its absence) instead of by the dynamics of biographical chronology. At times, it is difficult to wade through the pastiche of events—from enforced moves through the scenography for the play Presenting Jane to de Kooning’s first solo exhibition in 1954 at the Stable Gallery on West Fifty-Eighth Street, as well as a subsequent one held in 1956. All the while, stories about Willem de Kooning unfold—the Woman series, his rivalry with Jackson Pollock, his mother’s visit, his affair with another woman and the birth of their daughter, and his ensuing marital separation from Elaine de Kooning. The confusion is magnified by a combination of narrative approaches, ranging from retold anecdotes to detailed artistic analyses of the series of works on basketball players.

The sixth chapter, “Enchantment,” deals with her stay in New Mexico, her engagement with local art, the painters’ commune attached to the university, her pedagogical work, and impressions after meeting Georgia O’Keeffe. As Curtis explains, “When Elaine arrived in Albuquerque in the fall of 1958 as a visiting artist at the University of New Mexico, it was love at first sight” (91). Despite the differences between New Mexico and the New York scene, de Kooning was seemingly at ease when it came to fitting in at New Mexico. Cultural nomadism was never a problem for her. It was during this period that she began the series of bullfighting paintings, in which scenes of life, death, power, beauty, and tragedy unfold simultaneously, and which demonstrate a subtle balance between form and content. As she said, “Even in my abstractions, I have to have a theme” (98). And while de Kooning sympathized with the tragic role intended for the bull in this bloody spectacle—writing to a friend that she “hated the picadors” (99)—narration still gives way to painterly solutions. Blood is no longer blood, “it was simply red” (100).

The ensuing chapter, “Loft Life, Speaking Out, and European Vistas,” focuses on some of the spaces within which de Kooning lived and created and the objects she kept near her. It is interesting to note that in each of her studios, heaps of press clippings were regularly placed alongside her painting materials. It would appear that, despite her temperamentally-phrased observations that she did not care about what people thought of her, this bit of information, mentioned in passing, relativizes such claims.

In keeping with her character, de Kooning actively commented on numerous social and political issues. Her interest in the case of convicted murderer Caryl Chessman, for instance, resulted in a portrait of him, as well as efforts to commute his death sentence. She was the only artist to sign the Declaration of Conscience, printed in the leftist periodical Monthly Review, which supported the Cuban Revolution. She actively participated in the struggle for the rights of Indigenous people. She took part in the Peace Tower project in West Hollywood even though, interestingly enough, she did not believe in the power of art as a conveyor of protest messages. “Picasso’s Guernica was seen only by ‘the super-sophisticates,’ she said. ‘And it didn’t change anyone’s opinion one bit about stopping war’” (120). Instead, she was of the opinion that the role of art should be pragmatic—to help raise money for more effective methods of struggle.

As Curtis explains, de Kooning also distanced herself from the women’s liberation movement, saying “Women’s lib and feminism never seemed an issue to me, because as far as I was concerned, my mother ruled the universe. We had to be liberated from her” (120). The turbulent family relations of her upbringing and her apparent need for male attention, however, were not the only reasons she had for distancing herself from feminism. One should not overlook her lifetime credo based on opposing norms. De Kooning manifested her subversive disobedience toward given gender models, opposing both the heteronormative social matrix and its rejection by feminists. This resistance was tumultuous and did not allow for making compromises, either with herself or with others. This also explains why her art likewise cannot be described as feminist, even though the implications of her paintings are feminist, in the sense of their potential to destabilize the meanings and values of patriarchal culture.

Finally, in the same chapter, Curtis mentions de Kooning’s long-term problem with alcohol as an integral part of her life. She writes openly about it but is circumspect enough to steer clear of cheap sensationalism. Curtis treats De Kooning’s negligence, intransigence, sporadic lack of tact, and romantic liaisons in the same discreet manner.

Chapter eight, “Portraits as Moments and Memory,” thematizes the motif of portraiture in de Kooning’s painting—comparing its frequency to a dependence on smoking. We follow the genesis of some of her most successful works, such as the portraits of Willem de Kooning, Harold Rosenberg, Cunningham, and Frank O’Hara, as well as numerous portraits of women. These paintings present individuals from her social life and indirectly address her own belonging within this (elite) group, standing as testimonies of her disregard for conventions and (gender) norms.

The next chapter, “Painting the President,” describes the circumstances in which de Kooning’s best-known and most-analyzed series of works of John F. Kennedy came into being. Compared to stories about the creation of her other male portraits, the narrative around these images relativizes the idea of the absolute autonomy of creation, while pointing to artistic boundaries determined by the complex dynamics of social, political, and cultural models and expectations. The subsequent invitation to paint a portrait of the then-president for the Harry S. Truman Library in Independence, Missouri, is a testament to the fact that her work was very much appreciated, despite sporadic criticism.

Her artistic successes are emphasized even more clearly in the next chapter, “Caretaking and Cave Paintings,” in which scenes from her last studio inexorably impose comparisons with her first working and living spaces described at the beginning of the book. This chapter evokes the final years of Willem de Kooning’s life and her own illness and concludes with an emblematic anecdote. On the occasion of the opening of the exhibition Bacchus in Baltimore in 1980, somebody cracked the following joke: “The three questions not to ask Elaine de Kooning are, ‘How’s Bill?,’ ‘What did JFK say?,’ and ‘Why are you showing in Baltimore and not in New York?’” (179–80). These seemingly jocular and innocent questions sum up de Kooning’s lifelong displeasure at the way the interpretation of her art was chronically shaped through the qualification “de Kooning’s wife.” Equally, they suggest the ways in which the public followed her JFK portrait on account of the-one-painted, not because of the-one-painting, as well as the ways in which de Kooning’s unfulfilled expectations of recognition from the New York art world created a slow-burning disappointment within her.

Describing her never-completed memoirs toward the end of her life, de Kooning said that they would be “a history of the period” (192). This actually serves as a brief and all-encompassing assessment of A Generous Vision, the first complete biography of this artist. This meticulously researched and carefully written book precisely maps the artist’s life within the framework of the many spaces within which she worked. At the same time, it represents a fragmentary reconstruction of the topography of the New York art scene after World War II and the fates of some of its main protagonists. After putting the book down, the reader will undoubtedly feel acquainted with the life of Elaine de Kooning, from which her art came into being.

Cite this article: Simona Čupić, review of A Generous Vision: The Creative Life of Elaine de Kooning, by Cathy Curtis, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9988.

PDF: Cupic, review of A Generous Vision

About the Author(s): Simona Čupić is Professor in the Art History Department at the University of Belgrade