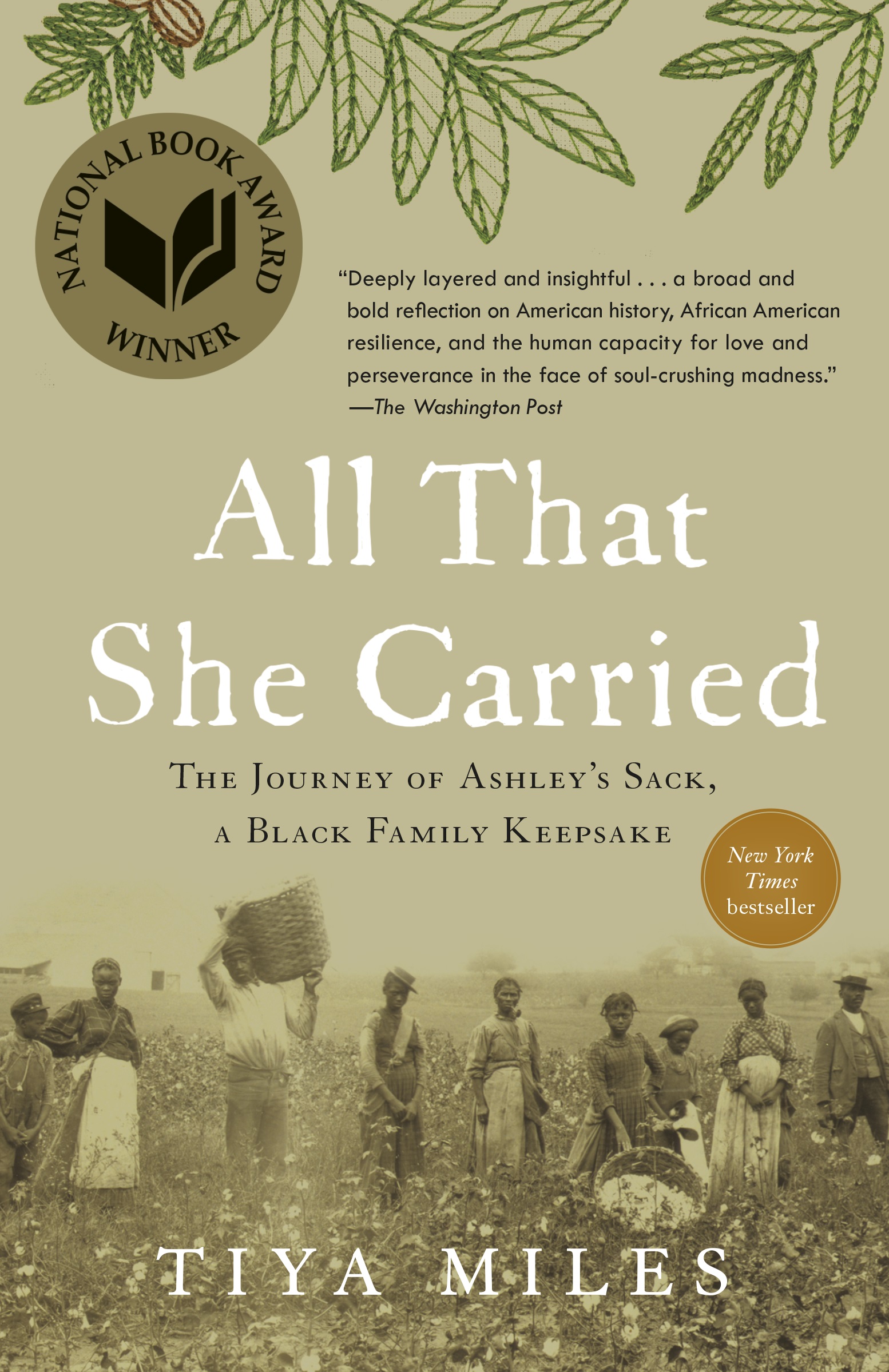

All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake

PDF: Yau, review of All She Carried

All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake

By Tiya Miles

New York: Random House, 2021. 385 pp.; 13 color illus.; 41 b/w illus. Hardcover: $28.00 (ISBN: 9781984854995)

The subject of Tiya Miles’s book All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake is an ordinary cotton sack, now held at the Middleton Place House Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, from which an extraordinary set of intentions, acts, and artistic expressions emerge.1 Measuring thirty-three inches long by sixteen inches wide, this utilitarian object from the mid-nineteenth century was made to carry food items—like flour, nuts, or seeds—necessary to physically sustain an enslaved workforce. But the embroidered verses on one side of the sack tells us that an enslaved woman named Rose repurposed it to carry weightier contents for nourishing her daughter’s mind and heart as well:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfuls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

To verify and chart the historical circumstances of an artifact of antebellum Black life is challenging enough, given the scarcity of archival records about the lives of the dispossessed. But what Miles accomplishes in her book is far greater and more consequential: she illuminates the contours of caretaking, remembrance, lineage, and love between generations of Black mothers and daughters that animate the journey of Ashley’s Sack. By focusing on Rose’s gift to Ashley and Ruth Middleton’s carefully stitched record of her family’s oral history, Miles tends to the silences of the past with fierce empathy for her subjects and their worlds.

The material structure of the sack as a textile and a container figures throughout, foremost as a metaphor for approaching “the conundrum of the archive” in understanding the lives of the enslaved (300). Miles cites historian Marisa Fuentes, who in probing the records of slave owners, slave sellers, and slaver jailers describes her archival strategy as reading “along the bias grain” (17) for the “tensile give” of the traditional archive, where records “can be stretched to reveal still more about individuals consigned to erasure” (65). Building on a stance first articulated by Saidiya Hartman, Miles interweaves a sense of loss and grief over their persistent absence in the archive, adopting “a trans-temporal consciousness and use of restrained imagination.” The impact is to “bring these women vividly into our minds while linking their circumstances and hard-won wisdom to great urgencies of our present moment” (18).

These approaches are poignantly in use in chapter 2, “Searching For Rose,” in which Miles casts a wide net on South Carolina plantation record books, slaveholders’ wills, estate inventories, property transactions, and textile distribution indexes for any mention of an enslaved woman named Rose. Miles takes readers along her research journey, pointing out that, while documents reveal nearly two hundred Roses, only three can also be linked to someone named Ashley. While Miles eventually leads readers to a Rose enslaved by one Robert Martin of Milberry Place Plantation, this fact seems to matter less than questions raised along the search: “The life of every enslaved Rose shines with its own worth and brilliance, even as their lives taken together illuminate . . . a society in which it was commonplace to both capture women and name them for flowers . . . Among these many Roses, how do we find and faithfully tell even one of their life stories?” (65). The longing to know and understand her subjects causes Miles to throw light against small historical facts and fill their silences with doleful wonder. For example, Miles learns from estate inventories that Ashley labored at Martin’s country plantation while Rose remained in his Charleston townhouse. Based on seasonal rhythms of the privileged, Miles writes, “perhaps Rose had chances to watch over Ashley there, giving the girl a hearth-baked bread or salvaged piece of pretty ribbon, and wishing she possessed the power to free her child from the invisible prison that she knew with a painful intimacy.” This turn to fictionalizing is not wistful nor wishful thinking but rather evidence of her approach as a public historian; she guides her audience to consider the value of historical voids and to resist “the default in which historical gaps feed contemporary forgetfulness” (89).

The risk of forgetting the “slave mother’s mind” (93) and that of her kin drives the investigations of the subsequent chapters. They are revelatory demonstrations of “thick descriptions” and close readings of objects and time periods that will be familiar to art historians and scholars of material culture. In chapter 3, “Packing the Sack,” Miles meditates on the when and why of Rose’s idea to give Ashley this emergency kit, offering a particularly moving account of hair as a site of corporeal control and a sentimental material of personal connection in the nineteenth century. Chapter 4, “Rose’s Inventory,” explores the many possible meanings of the tattered dress as a hard-earned commodity for the unfree and as a symbol of self-possession. In chapter 5, “The Auction Block,” Miles investigates the scene of Ashley’s separation and the horrible economics that motivated it. Chapter 6, “Ashley’s Seeds,” focuses on the handful of pecans that could serve as sustenance and seed. This item gives a window onto enslaved people’s roles in agriculture (we learn of Antoine, the first cultivator of the pecan tree), as well as Black and Indigenous foodways that have grounded communities and tended to the land. The final chapter, “The Bright Unspooling,” centers on Ruth’s position in Philadelphia’s Black middle class and the significance of sewing, rather than writing, the story of Rose and Ashley on the sack. Miles carefully attends to Ruth’s embroidery as both a historical document and poetic work, “greeting her ancestors, welcoming them into her memory and into reunion with one another” (263). Throughout, sensory experiences of touch, smell, and taste animate Miles’s evocative passages about Rose, Ashley, and Ruth’s lived experiences.

The radiant power of Ashley’s Sack grows brighter as each chapter builds on the others, in large part due to Miles’s staggering research. Precious notes from enslaved and recently escaped people, along with other primary sources, demonstrate how Rose and Ruth did not act alone per se. Their decisive acts were like those made by generations of dispossessed African Americans who activated mundane things, like a lock of hair, a quilt, or coins, as tools in the ongoing struggle for freedom and dignity. In this vein, of particular note is the special status of fabric in African American women’s history discussed in the book’s conclusion. Surveying fabric’s material qualities—its woven structure, its connectedness to everyday life, its fragility under repeated uses and washings, and its nearness to the body, among other comforting, intimate presences—she argues that fabric is a medium for life itself (271–73). In “Carrying Capacity,” a visual essay composed with Michelle May-Curry featuring artworks by Kelly Taylor Mitchell, Letitia Huckaby, Rosie Lee Tompkins, Sonya Clark, Marianetta Porter, and Miles’s great-aunt Margaret (whose quilt is reproduced in part) function as fellow light and wisdom bearers. Printed in color plates, this novel addition to the book illustrates how the far-reaching lineage for Ashley’s Sack extends into the present.

The shifts between literal and social fabric that permeate All That She Carried serve the book’s ultimate argument for the practice of love essential for survival in times marked by loss, trauma, and existential threat. Defined simply in the prologue as “decentering the self for the good of another” (3), love, as discussed in Miles’s final pages, shows its reparative potential “for new kinds of wholeness” (277), which she urges that her readers adopt for a different, more equitable kind of future: “We are the ancestors of our descendants. They are the generations we’ve made. With a ‘radical hope’ for their survival, what will be packed into their sacks?” (xvii). In a time when political assaults on education, historical truth telling, and civil discourse intensify almost daily, Miles’s case rings loudly and more urgently than ever. Responding to All That She Carried is a bit like translating some of the profoundly visceral responses that visitors have had upon seeing Ashley’s Sack on museum display: it is the sum of many things, all at once.

The winner of ten book prizes, including the National Book Award for nonfiction, this is a riveting story of a single object and the generations of women who cared for it, told with honesty and rigor. Immensely readable in its translation of academic ideas for general audiences, its appeal for ethical action exemplifies the best of public humanities scholarship. It is also an accessible teaching tool. Any student of African American Studies, women’s history, and material culture will learn from Miles’s notes on terminology and reflective essay on process, which provide personal insight into her scholarly journey and the community insights that bloomed into the book’s final form. Complete with meticulous footnotes, Miles’s book is a touchstone for scholarship that stays close to its harrowing themes while showing us a more hopeful way forward. Such is the generosity of the best teachers.

Cite this article: Elaine Y. Yau, review of All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake by Tya Miles, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 2 (Fall 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18149.

Notes

- From 2016 to 2021, Ashley’s Sack was exhibited at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, before returning to the Middleton Place House Museum in Charleston, South Carolina. Plans are underway to display it again in Charleston’s International African American Museum. See “Ashley’s Sack: How Much Can One Bag Carry?” Middleton Place, June 6, 2021, https://www.middletonplace.org/news-and-events/ashleys-sack-how-much-can-one-bag-carry. ↵

About the Author(s): Elaine Y. Yau is associate curator at the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, where her primary area of care is the African American Quilt Collection.