Douglass’s Pictures, Julien’s Lessons

PDF: Murokh, Douglass’s Pictures, Julien’s Lessons

To walk into the deep-red ambient surround of Sir Isaac Julien’s (b. 1960) Lessons of the Hour (2019) is to enter the chilling synchrony of the tumultuous mid-nineteenth century and our own early twenty-first (fig. 1).1 Part sonic collage, part biographical tribute, part historical re-envisioning, this multiscreen installation, running just under twenty-nine minutes, gives audiovisual form to the powerful presence and rhetorical eloquence of the nineteenth century’s most photographed American—the self-emancipated author, orator, and abolitionist Frederick Douglass (1818–1895).

The last two decades have witnessed a surge in scholarly and popular interest in Douglass, revisiting his investment in the human capacity for “picture-making” and “picture-appreciating,” generally, and the liberatory potential of photography, in particular.2 In art history, Douglass’s present-day resonance is overdue, given his insistence on the relationship between pictures and progress.3 The convergence of politics and aesthetics has been at the center of this renewed attention, not only in academia but also in contemporary art, from Rashid Johnson’s photographic Self-Portrait with My Hair Parted Like Frederick Douglass (2003) to Charles Gaines’s performance-based installation Manifestos 4: The Dred and Harriet Scott Decision (debuted in 2020 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art).4

Like the historical man, Julien’s Douglass is ever on the move. Following the celebrated reception of the work premiered at the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester in 2019, it has been on view in many venues, recently including the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (December 10, 2022–July 9, 2023), the Museum of Modern Art in New York (May 19–September 28, 2024), and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, DC (starting December 8, 2023), where it will be up through the 250th anniversary of the founding of the United States after being jointly acquired by SAAM and the National Portrait Gallery. Still more installations are to come. The current circulation of Julien’s Lessons suggests it might be understood as an apex of contemporary Douglassiana, to play on antiquated verbiage denoting the material record of mass-cultural popularity. Douglass, in other words, is having yet another life as an American icon—this time in art museums, institutions regarded as some of the most decisive arbiters of culture.

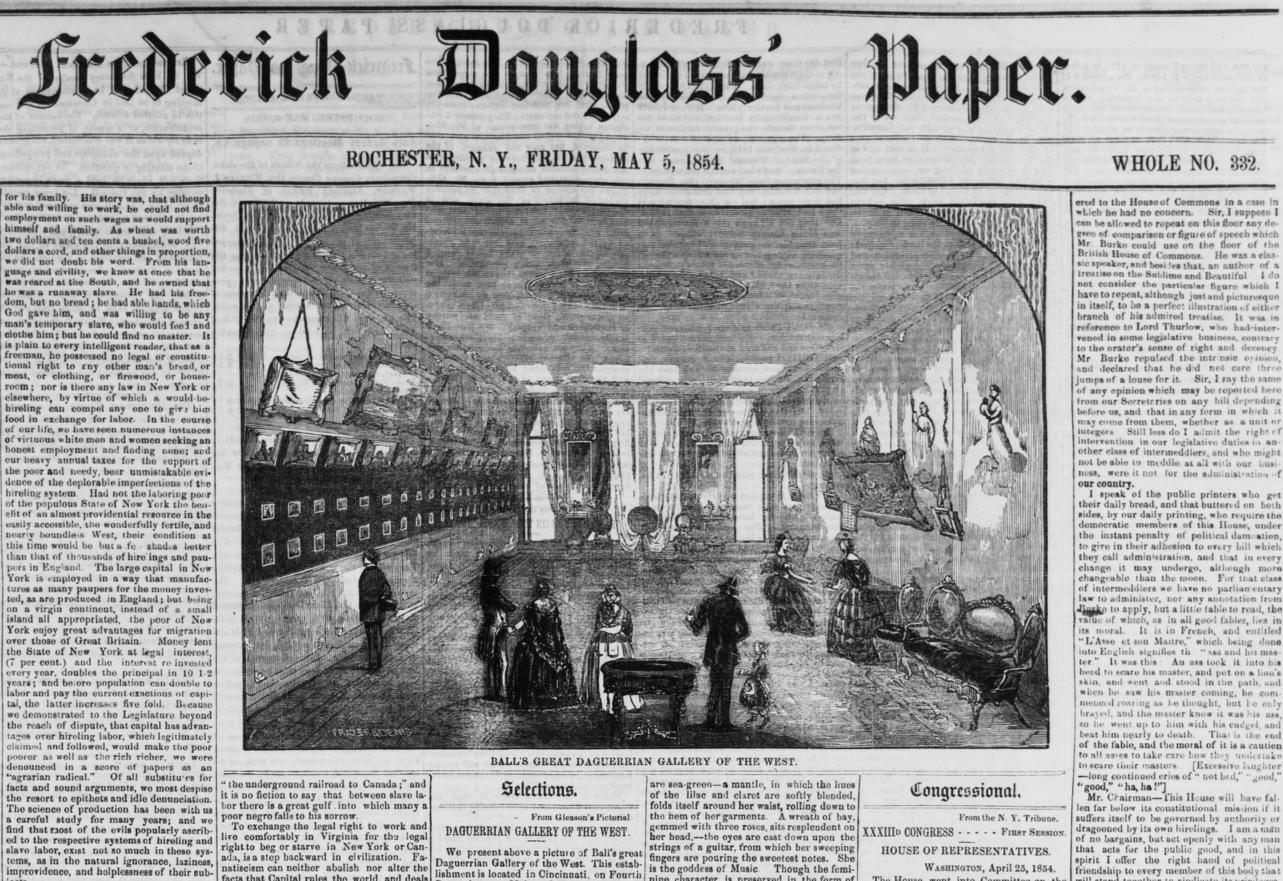

In Julien’s rendering, actor Ray Fearon dons the orator’s recognizable hairstyle and journeys between landscape and lectern; among the represented elsewheres, he sits for a photograph in J. P. Ball’s “Great Daguerrian [sic] Gallery of the West” (fig. 2).5 As in this prolonged scene, much of the time Fearon’s Douglass is speaking with an empowered depth of feeling that takes on even greater poignancy later in the piece as Julien transitions from his high-definition rendering of Douglass’s nineteenth-century world to a grainier view of ours. As Douglass continues to speak over surveillance footage of protests following the 2015 killing of Freddie Gray Jr. in police custody and Fourth of July fireworks, Julien redirects Douglass’s oratory against the contemporary media environment and our attendant spectatorial practices, critically indicting the ways in which brutality against Black people is and has always been entwined with celebrations of nationhood.

Importantly, Douglass’s lectures were not only about photography; they were also about the stakes of transforming the world into a series of pictures and the attendant practices of viewing and response. Julien’s screens of different sizes and in nearly overlapping positions echo the salon style of nineteenth-century art exhibitions, on the one hand, and the frenetic multimodal, audiovisual experience that marks contemporary life, on the other. Under both regimes, pictures compete for the viewer’s focus while also assembling a more totalizing view.

Noting that pictures circulate and signify within structures, Douglass once remarked that “the portrait makes our president,” elaborating that “the political gathering begins the work and the picture gallery ends it.”7 If pictures themselves can be institutionalized, they are also agents of institution building. By transforming the galleries of today’s museum into sites of re-encounter with the presentness of the past, Julien’s Lessons folds the institution of pictures back onto itself, calling into question not why Douglass should be or remains an icon today but rather how Douglass might circulate within institutions as more than image or symbol.

If art historians and gallery-goers are willing to face Julien’s Lessons, the work must be recognized as more than contemporary art speaking back to history and against the failures of the present. Julien’s installation raises Douglass’s concerns with representation and power, to be sure, but it also signals a cognizance of the ways in which real and imagined images constitute a worldview that institutions cultivate and affirm. Spaces for pictures have long been mobilized literally and rhetorically toward social and political meaning, and we must challenge ourselves to resist the pull of narrow presentism as we work to imagine and enact new conditions for art and/in community. By presenting Douglass’s way of seeing—a period eye responsive to the rapid proliferation of media, industrialization of image production, and increased interpolation of mass and high culture—Julien demonstrates the possibility of seeing like Douglass, rather than only seeing Douglass. To really see Douglass through Julien, then, is not to recognize each man’s greatness or rely on the artist or his subject to have the last dissenting word but to reckon with the continuities that we cannot avoid once we choose to look and to listen.

Cite this article: Dina Murokh, “Douglass’s Pictures, Julien’s Lessons,” in “American Artists x American Symbols,” ed. Katherine Jentleson, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 2 (Fall 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19431.

Notes

- On Julien’s Lessons of the Hour, see Isaac Julien and Cora Gilroy-Ware, eds., Isaac Julien: Lessons of the Hour; Frederick Douglass (London: Isaac Julien Studio; Rochester, NY: The Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester; Saratoga Springs, NY: The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Gallery at Skidmore College; New York: DelMonico Books • D.A.P., 2021). ↵

- Frederick Douglass, “Pictures and Progress” (1864), published in John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier, Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American (New York: Liveright, 2015), 170. In addition to Picturing Frederick Douglass (2015), on Douglass and pictures see, for instance, Henry Louis Gates Jr., “Frederick Douglass’s Camera Obscura: Representing the Antislave ‘Clothed and in Their Own Form,’” Critical Inquiry 42, no. 1 (Autumn 2015): 31–60; Celeste-Marie Bernier, “A Visual Call to Arms against the ‘Caracature {sic} of My Own Face’: From Fugitive Slave to Fugitive Image in Frederick Douglass’s Theory of Portraiture,” Journal of American Studies 49, no. 2 (May 2015): 323–57; Celeste-Marie Bernier, “A ‘Typical Negro’ or a ‘Work of Art’? The ‘Inner’ via the ‘Outer Man’ in Frederick Douglass’s Manuscripts and Daguerreotypes,” Slavery & Abolition 33, no. 2 (2012): 287–303; Marcy J. Dinius, “Seeing a Slave as a Man: Frederick Douglass, Racial Progress, and Daguerreian Portraiture,” in The Camera and the Press: American Visual and Print Culture in the Age of the Daguerreotype (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 192–232; Ginger Hill, “‘Rightly Viewed’: Theorizations of Self in Frederick Douglass’s Lecture on Pictures,” in Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity, ed. Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 41–82; Laura Wexler, “‘A More Perfect Likeness’: Frederick Douglass and the Image of the Nation,” Yale Review 99, no. 4 (October 2011): 145–69; John Stauffer, “Frederick Douglass and the Aesthetics of Freedom,” Raritan 25, no. 1 (Summer 2005): 114–36. See also Robin Kelsey’s discussion of photography and Douglass’s ideas in the context of shifting notions of the picture in “Pictorialism as Theory,” in Picturing, ed. Rachael Z. DeLue, Perspectives in American Art (Chicago: Terra Foundation for American Art, 2016), 176–211. ↵

- The phrase “pictures and progress” references one of the titles as well as the broader theme of Douglass’s early 1860s lectures on the topic. See Stauffer, Trodd, and Bernier, Picturing Frederick Douglass. ↵

- See Shawn Michelle Smith’s chapter on Johnson and Douglass in Photographic Returns: Racial Justice and the Time of Photography (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 16–33. I am indebted to Sora Han for bringing the Gaines work to my attention through her own engagement with it. ↵

- James Presley Ball was a Black photographer and entrepreneur working in Cincinnati in the mid-nineteenth century. Julien’s reimagining of the interior of Ball’s studio references a view captioned “Ball’s Great Daguerrian {sic} Gallery of the West” reproduced in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, following its circulation in Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion in April 1854. Ball is also known for the Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States Comprising Views of the African Slave Trade (1855). On Ball, see Deborah Willis, ed., J. P. Ball: Daguerrean and Studio Photographer (New York: Garland, 1993). A recent installation at SAAM addressed Ball’s well-known collaboration with painter Robert S. Duncanson (2023–24), https://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/ball-duncanson. ↵

- “Rightly viewed, the whole soul of man is a sort of picture gallery, a grand panorama, in which all the great facts of the universe, in tracing things of time and things of eternity, are painted.” Frederick Douglass, “Lecture on Pictures” (1861), in Stauffer, Trodd, and Bernier, Picturing Frederick Douglass, 131. ↵

- Frederick Douglass, “Age of Pictures” (1862), in Stauffer, Trodd, and Bernier, Picturing Frederick Douglass, 143. ↵

About the Author(s): Dina Murokh is assistant director of the Graduate Program in the History of Art, Williams College.