Teaching and/as/in Marie Watt’s Sewing Circles

PDF: Hecht and Stang, Marie Watt’s Sewing Circles

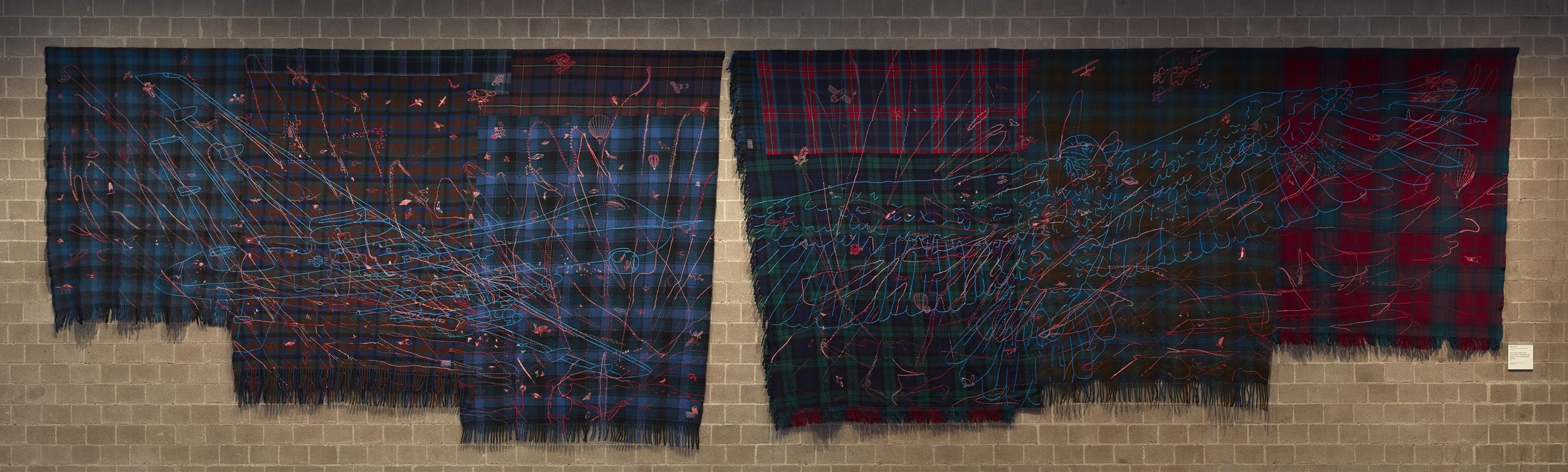

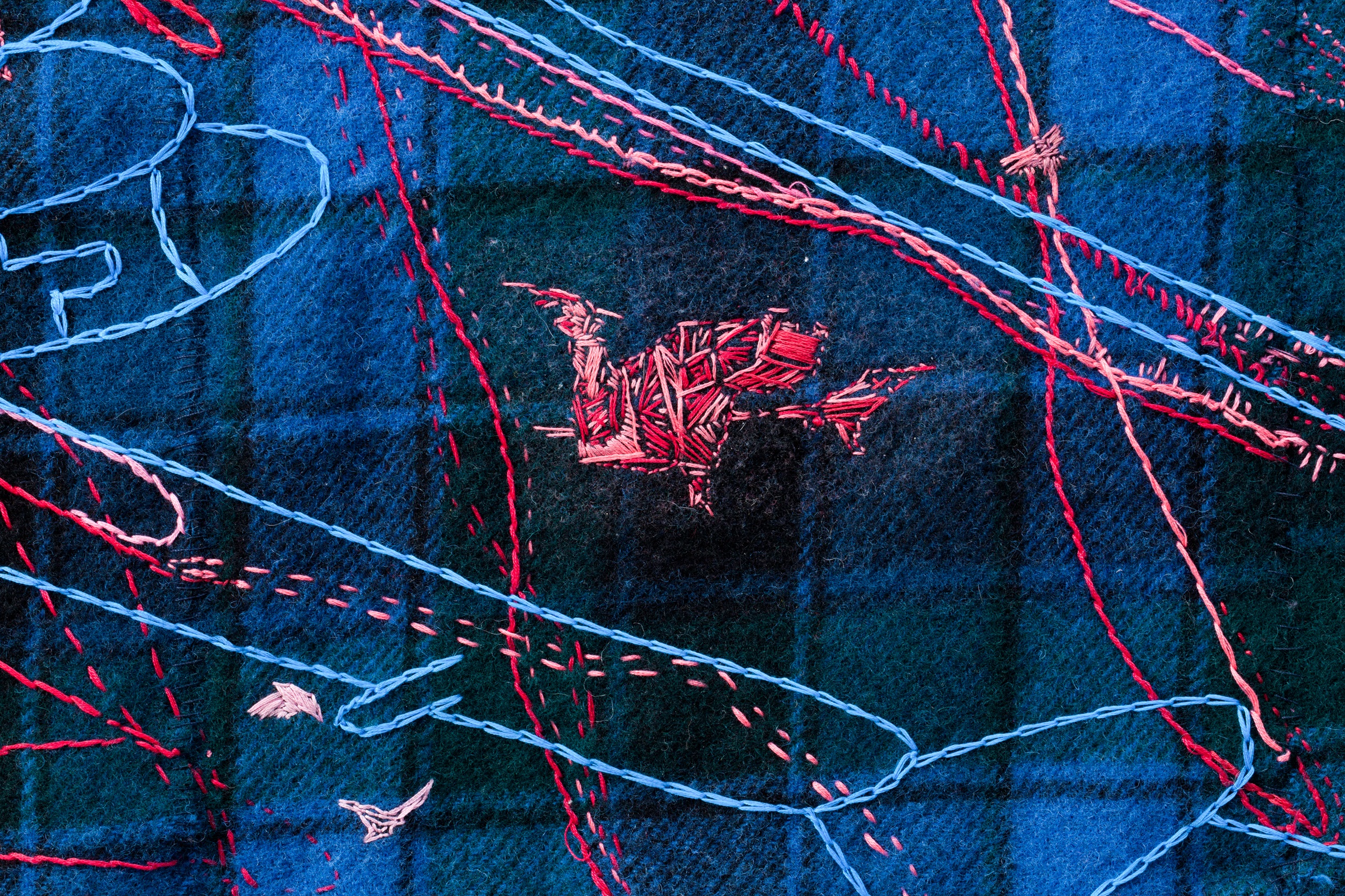

Since 2019, Seneca artist Marie Watt’s textile pieces comprising First Teachers Balance the Universe—Part I: Things That Fly (Predator) and Part II: Things That Fly (Prey)—have been on display at the Yale University Art Gallery (YUAG) in New Haven, Connecticut (fig. 1). The works total twenty-three feet in length and six feet in height and are made from Pendleton wool blankets that hang next to one another, creating the effect of a giant bird’s wingspan. Part 1: Things That Fly (Predator) includes an enormous US military drone in electric-blue thread; Part 2: Things That Fly (Prey) depicts an equally large bald eagle. Both pieces bear embroidery made by individuals participating in Watt’s sewing circles, in which she invites the public to contribute to her process. Many hands added small birds, hot-air balloons, UFOs, and even a tiny Millennium Falcon, all rendered in colorful thread. For Watt, the sewing circle fosters powerful dialogue that can only emerge “when your eyes are diverted and you’re working with something as familiar and intimate as cloth.”1 But the pieces also invite conversation long after the circle has closed.

Over the past six years, we have been YUAG Gallery Teachers while completing our doctoral studies. As we have taught from First Teachers to countless community and university groups, we have been taught by the work, and we have come to appreciate Watt’s approach, which is as much about pedagogy as it is about craft. Mirroring the collaborative spirit of the sewing circle that created First Teachers, we have reevaluated two primary methods for teaching American art through our museum practices.

While at YUAG, we have questioned what it means to teach about the United States during a time when American art education is heavily influenced by the Yale scholar Jules Prown, whose pedagogical methods are embraced across the field, including in this journal. Prown advocated for a looking process built on a sequence of description, deduction, and speculation.2 Museum pedagogy often relies on a cousin of this “Prown Method,” known as Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS). VTS directs educators to “allow the conversation to go where it will” and to “avoid inserting information” in order to encourage open discussion and critical thinking.3 You can gently correct but only when necessary. We have found, however, that works like First Teachers require a different methodology.

The danger with the Prown Method or VTS is that many of the student-viewers we have encountered can name American signs associated with settler histories but not with Native American histories, resulting in a reconstitution of dominant interpretations fostered by a museum setting that is itself implicated in colonialism. Without receiving context or appropriate language in a timely fashion, a learner can feel that their teacher is setting them up to fail. For Watt, the multigenerational and cross-disciplinary sewing circle reminds us that “teachers are learners and learners are teachers.”4 Even though we ourselves have never joined one of Watt’s circles, they have inspired us to stoke more community-based knowledge production with our teaching. This shift means that we as teachers learn about our community’s notions of American history, and the students walk away with new ways of complicating those notions.

When discussing First Teachers, we lean into approaches that promote intersubjective looking and embodied learning. In one activity, we ask viewers to draw a detail from the piece and to write a question about it. They then pass their paper to the person next to them, who will draw another detail and write another question. We continue this until each paper returns to its original owner. We move into the next stage of the activity when we prompt the group to share a question from their paper that surprises them most.

We do not let the group rely only on what they can see in isolation. Rather, we answer their questions, pushing them to look deeper as they learn about Pendleton’s appropriation of Indigenous designs in their blankets, the flying animals at the heart of the Seneca creation story, or the fact that the big blue plane is a Predator drone (fig. 2). Regardless of the type of groups we have brought before First Teachers—ranging from corporate retreats to homeschool classes—we have never felt resistance to the piece’s critiques of the United States. We always manage to have transformative conversations when we collectively sew the work’s meaning anew out of each group’s curiosities. This approach empowers viewers to be informed “co-investigators” of American history, as well as of art’s power to tell another story.5

First Teachers provides a pedagogical model for decolonizing museums and universities. Each viewer brings their own stitch to American life. So, too, the teacher has a stitch. At this piece, we come together in an exchange that is inspired by Watt’s collective making practice and by an Indigenous worldview that honors communal knowledge over emphasis on the individual in an effort to disavow colonial erasure. We build on scholar Amy Lonetree’s contention that “a decolonizing museum practice must be in service of speaking the hard truths of colonialism.”6 In our teaching, we ease students into communal conversation about these hard truths, with the hope that viewers can examine their assumptions and prejudices about complicated American iconography.

Cite this article: Charlotte Hecht and M. Stang, “Teaching and/as/in Marie Watt’s Sewing Circles,” in “American Artists x American Symbols,” ed. Katherine Jentleson, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 2 (Fall 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19334.

Notes

- Robin Cembalest, “An Artist Sews a Sense of Community,” Yale Alumni Magazine (March/April 2021), https://www.yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5271-an-artist-sews-a-sense-of-community. ↵

- Jules David Prown, “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method,” Winterthur Portfolio 17, no. 1 (April 1982): 1–19. ↵

- This language is repeated across VTS training materials, but see, for an example, Milwaukee Museum of Art, “Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS)—Teacher Resources,” accessed August 21, 2024, http://teachers.mam.org/collection/teaching-with-art/visual-thinking-strategies-vts. ↵

- Marie Watt, “In Conversation with Marie Watt: A New Coyote Tale,” Art Journal 76, no. 2 (April 3, 2017): 124–35. ↵

- For a more in-depth account of YUAG’s Gallery Teacher training, see Jessica Sack and Rachel Thompson, “The Wurtele Gallery Teacher Program Method: A Practical and Experiential Approach to Training Cohorts of Museum Educators,” Journal of Museum Education, August 4, 2024, 1–11. ↵

- Amy Lonetree, Decolonizing Museums Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012). ↵

About the Author(s): M. Stang is joint PhD candidate in American studies and film & media studies at Yale University, as well as a Wurtele Gallery teacher at the Yale University Art Gallery. Charlotte Hecht is a PhD candidate in American studies at Yale University and a Wurtele Gallery teacher at the Yale University Art Gallery.