Lifting the Lid on Cigar Boxes at Winterthur

Last spring, I found enlightenment in the Winterthur Library. I was there to look for images of nudes on tobacco advertisements, and I did find some, but also stumbled across some surprising and unexpectedly beautiful chromolithographs that provided an epiphany about the relationship between censorship and culture at the turn of the twentieth century. The objects that inspired this new thinking were cigar boxes and the labels that adorned them.

The project that brought me to Winterthur is my forthcoming book, Lust on Trial: American Art, Law, and Culture during the Reign of Anthony Comstock (Columbia University Press, forthcoming 2017). Nearly ten years ago, I decided to try and recover the visual culture censored by Anthony Comstock during his years as the nation’s first federally appointed censor, from 1872 until his death in 1915. My work began with a broad array of guiding questions. What can suppressed materials tell us about the evolution of sexuality, gender, art, and law during this time? How and why did standards for obscenity devolve so far and so fast? How did shifts in legal liability change the choices made by artists, publishers, and consumers? And finally, what does this history teach us about the general effectiveness and significance of censorship that might be applicable to our own complicated moment?

The field guides for finding Comstock’s censored materials are the arrest records of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV). Comstock served jointly as an inspector for the United States Post Office Department and as the secretary and agent of the NYSSV, a private and evangelical Christian organization. In this capacity, Comstock was invested with the authority to seize materials he deemed obscene under federal postal laws, as well as a variety of state laws he helped to pass. For more than forty years, Comstock diligently recorded every defendant and seizure in detail in these arrest records, distinguishing even between types of printing plates, formats of photographs, and materials used in manufacturing immoral objects, such as sex toys and contraceptives. Images and objects with listed titles were easy to locate using databases and letters to archivists. Some other types of materials, however, were harder to find. Comstock seized hundreds of thousands of pieces of ephemera, including vast quantities of tobacco advertising, but he provided little detail beyond his colorful judgments about what he deemed was their level of filth.

A case in point is the trial of John Blakely, a cigar dealer at 233 Broadway in lower Manhattan. At the time of his arrest in 1892, Comstock described Blakely as an atheist who “stocked himself with the most obscene matter to draw trade. He gave vile matters away.” Comstock’s seizure included more than one thousand prints as well as one “large picture in frame.”1 There was not a specific title listed in that haul, but it seemed reasonable to search for images in tobacco advertisements that were censored in other media. Thankfully, several ephemera collectors have focused on tobacco, including Tony Hyman, founder of the National Cigar History Museum, and John and Carolyn Grossman, whose vast collection of trade cards and cigar labels is now owned by the Winterthur Library.2

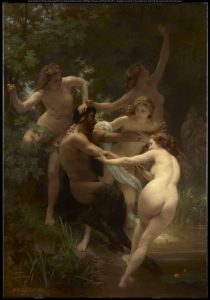

As I looked through folders in the Winterthur Grossman Collection, I was immediately struck by how many images had migrated from high art to tobacco advertisements via censored reproductions of French academic paintings of nudes. A case in point is the enormous painting by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Nymphs and Satyr (fig. 1).

From 1882 to 1901, the painting was the featured attraction in the saloon of the Hoffman House Hotel on Madison Square in Manhattan, where it hung underneath a red velvet canopy. The lighthearted subject of the work undoubtedly contributed to its popularity. In the playful concoction by Bouguereau, a lusty satyr has been caught spying on a group of nymphs who now are taking their vengeance by dragging him into a nearby pond. Satyrs cannot swim, and so his lust has been swiftly transformed into mortal terror.

The eroticism of the scene is highlighted not only by the copious exposed flesh visible, but also especially by the flesh that is pressed together in the scene, including the prominent left arm of the satyr against the breasts of the nymph behind him. The artistry of Bouguereau’s technique in these passages is exquisite. As Fronia Wissman writes: “the brushstrokes are almost invisible. The contemporaneous term was leché, “licked.”3 By 1885, the nymphs had become so famous that a tourist guide printed that year advised: “Ladies can see this superb work any morning before ten o’clock.”4 Two years later, Nymphs and Satyr was still rising in popularity and fame. A critic writing in The Connoisseur in 1887 went so far as to credit the infamous bar and its celebrated painting “with the distinction of inaugurating the alliance between art and cocktails.”5

Although he had the legal authority to do so, Comstock did not have the political power to force Edward S. Stokes, the Hoffman’s wealthy, well-connected, and infamous proprietor, to remove the nymph painting from his saloon. Comstock was able, however, to convince a New York State Appeals Court to rule that reproductions of the painting were illegal, because they would “deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.”6 This test of obscenity technically held sway from 1883 until 1957, although it was enforced erratically at best.7

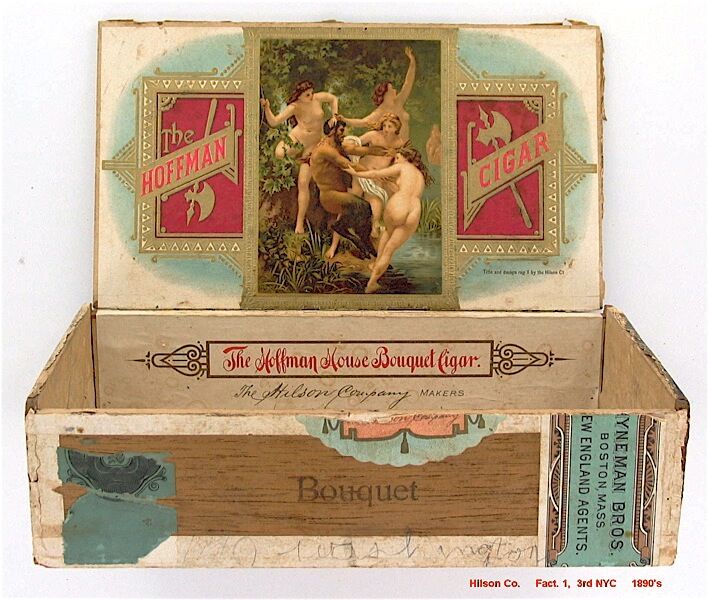

How did Americans react to the attempted suppression of reproductions of art such as Bouguereau’s Nymphs and Satyrs? Material culture such as cigar labels demonstrate that many Americans were unconvinced that they would be ‘depraved and corrupted.’ Instead, they had fun and made money. Recognizing the public appeal and commercial potential of Bouguereau’s notorious Nymphs and Satyr, the owners of the hotel used the work in abundant promotions. Most notably, the Hoffman House issued its own brand of cigars with the nymphs as decorative labels starting soon after the ruling of the appeals court. On the interior of the cigar box lid, (fig. 2), a designer even added decorative hatchets on either side of the nymphs, subliminally reinforcing the misandrist overtones in the painting. Other label designers used the nymphs as a starting point for humorous flights of fancy.

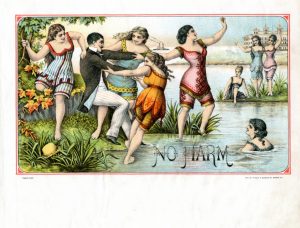

In 1894, the firm of Witsch and Schmidt parodied Bouguereau’s famous work in a cigar box label in the Grossman Collection, titled No Harm (fig. 3).8 The satyr in this case has been transformed into a well-dressed dandy, who presumably will suffer no harm when he is deposited in the water by a group of strong and determined women in risqué bathing costumes. In the upper right corner of the label, the massive Brighton Beach Hotel at Coney Island is visible, transporting the nymphs from verdant woodlands into a setting known for its outrageous and innovative entertainments, many of them geared toward young working women.9

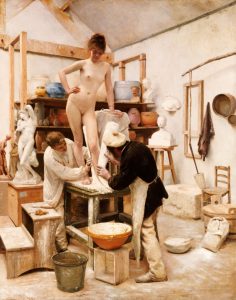

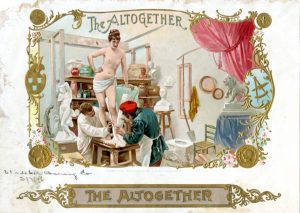

Another great example of an image that migrated from fine art to advertising owing to Comstock’s censorship efforts is Édouard-Joseph Dantan’s painting, Un Moulage sur Nature (fig. 4). Dantan’s original painting depicted two sculptors taking a cast from a model’s leg. To highlight the venerable tradition of sculpting from life, Dantan included at bottom left both a copy of Christophe-Gabriel Allegrain’s sensual statue of a nude, Bather, (also known as Venus) , as well as Michelangelo’s languorous Dying Slave.10 He also added a note of humor by depicting three busts in the background all gazing in amusement at the artistic action. The model’s clean-shaven and pale skin is intended to represent the aesthetics of classical and Renaissance sculpture, such as that of Michelangelo, but Dantan has made her face and lower arms quite visibly pink—a touch of realism that reviewers often complained about in contemporary French academic painting. The same year the painting was shown in the 1887 Salon in Paris, Comstock seized reproductions of the work as part of a raid at Knoedler gallery in New York.11 Press coverage of the case was explosive. Within days of the Knoedler raid, the New York Evening Telegram cheekily published line drawings of every picture seized. Dantan’s Un Moulage sur Nature was featured on page one.12

The painting was known in America only through reproductions with a limited circulation and the line drawing published in The Telegram. Nevertheless, Comstock’s prosecution made it famous. An enterprising artist working for George Schlegel’s prolific commercial design firm in lower Manhattan repurposed Dantan’s work as the decorative highlight of a cigar box label in 1896 (fig. 5). Given the fidelity of the copy, it is highly likely that the designer began with a photographic reproduction of the painting, then added a tiny swag of drapery at the pelvis of the nude. For some enhanced glitz, the designer also added a frame including a gold easel and palette, and several decorative medallions that lend an air of artistic acclaim. The title, The Altogether, was well known in the mid-1890s as a key bit of dialogue in George du Maurier’s novel Trilby, which appeared in serial form in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine and then as “the first novel to be named after an artist’s model” in 1894.13 The phrase also was key within an infamous theatrical sketch titled “Ten Minutes in the Latin Quarter” in 1896, in which the actress Hope Booth portrayed a poor young woman who takes up modeling for an artist.14 With its mixture of associations from Michelangelo to the vaudeville stage, the label achieves a perfect integration of rarified high and saucy low.

Prior to visiting the Winterthur Library, I had not realized how frequently images censored by Comstock reappeared in commercial art, as straightforward copies, parodies, or modified, less spicy versions. Owing to the profitable publicity created by Comstock’s censorship, artists had strong incentive to utilize these images. As I also discovered upon seeing the originals at Winterthur, the chromolithographic trimmings designed for the interiors of the boxes were elaborately crafted and extremely beautiful, with as many as twelve separate layers of color, elements of sculptural dimension from pressed paper foundations, and the glitter of applied gold highlights. A third epiphany was more logistical and conceptual in nature. There were indeed plenty of images Comstock considered obscene on cigar boxes—but only on the inside of the lid. The exteriors of cigar boxes contrastingly were rarely saucy. I definitely had not realized this from looking at examples of labels online and in the catalogue written by John Grossman.

Winterthur Librarian Jeanne Solensky helped me understand how cigars typically were packaged in rectangular wooden boxes adorned with elaborate decorative prints, known as trim: “A full set of trimmings consisted of several labels. A label on the inside of a box usually measured 6” x 9,” while an outer label was smaller at 4 ½” x 4 ½” or 2” x 5.” To add decoration while hiding box construction, edging strips were placed over hinges attaching lids to boxes and small tags covered nails.” The smaller size of the exterior trim was necessary to leave room for tax stamps, cigar maker identification, and cautionary notices.15

The difference between outside and inside helps explain why Comstock does not specifically record suppressing the boxes themselves. Cigar stores typically displayed their wares inside their stores, in humidified cases with box lids open to offer a view of the dazzling artistic labels. As long as the nudes were visible only to the type of wealthy gentlemen who frequented tobacco stores selling entire boxes of cigars, Comstock ignored them. He was on this beat only when the boxes migrated to the shop window. In the NYSSV’s Annual Report for 1904, he complained: “we discovered in certain cigar stores in the lower part of the city, certain pictures displayed upon the inside of cigar boxes, which were placed in the window so that boys and girls passing could see them. . . . There had been convictions upon this same picture, but this firm did not know of it.” Rather than seek an indictment, Comstock reported that he called the tobacco company, and the vice president “ordered them removed.”16

Although it is possible that Comstock got what he wanted in this one small instance, the flood of nudes that continued to proliferate in the United States in the early twentieth century belies any claim that this type of censorship was effective in the big picture. Censorship efforts undeniably fueled incinerators with seized materials, sent many to jail, and created fear of suppression, which begat self-censorship that served the same repressive purpose. But in other important ways, Comstock’s acts of censorship doomed their own objectives. As cigar box labels demonstrate, the regulatory restraints that provoked a chill in some, such as the tobacco executive, contrastingly provoked enthusiasm in others, including commercial artists who were happy to take advantage of the opportunity Comstock created for enhanced sales. On balance, the latter effect seems to have been much more potent.

American public culture was indisputably more filled with sexual images in 1915 when Comstock died than when he began his career in 1873, despite the forty-three years he had worked so aggressively to suppress them. Comstock himself traced the course of this path in discussing the evolution of theatrical entertainments in 1901:

There are many living to-day who can remember the first production upon the stage of the “Black Crook,” who will recall the storm of indignation which its gross features aroused. That was an entering wedge. Little by little since then, the managers of play-houses have been catering to depraved tastes, until, now, things indescribably vile are placed upon the public stage to meet the demands of a debauched public taste and desire. Dives of blackest hue are run openly, patronized by well-dressed persons, persons often moving in decent society and in the churches, who sneak into these abominable pest holes for personal entertainment.17

Comstock no doubt felt that the situation between 1901 and 1915 further degenerated, with the advent of new technologies, such as Kinetoscopes and nickelodeon movie houses catering to debauched tastes for a vaster swath of Americans of every class status.

Comstock spent his life attempting to suppress public displays of bare flesh, but even when he cleared a stage or shop window, he never was able to halt the social and technological changes that doomed his efforts. More often than he would have liked to admit, the images he attempted to suppress did not disappear, but instead migrated to other media, and often new audiences. In the same years that commercial artists imported nudes from French academic painting onto cigar box labels, many more American painters and sculptors were inspired to take up similar subjects for the first time. The leading examples include Kenyon Cox, John La Farge, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and Frederick MacMonnies. A new generation would soon follow their example, including George Bellows, Everett Shinn, John Sloan, and Robert Henri.

My valuable epiphany at Winterthur was that cigar boxes are perfect evocations of the effects of censorship. The exteriors may have been sanitized in satisfaction of legal requirements, but that did not change the picture underneath the censored surface. Anthony Comstock undeniably was effective at suppressing an enormous quantity of visual culture. Much more impressive is what he never could suppress: dazzling displays of American playfulness, entrepreneurship, sexuality, technological innovation, and social transformation. Going forward, I would suggest that scholars who want to track changes in the aesthetics and subject matter of high art in America at the turn of the twentieth century spend some time going low—downstairs to the basement of the Winterthur Library.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1571

PDF: Werbel – Lifting the Lid on Cigar Boxes at Winterthur

- “Names and record of persons arrested under the auspices of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice” 2 (July 21, 1892), 226–27, Library of Congress. ↵

- I am grateful to Henry B. Voigt for suggesting that I consult the Grossman Collection. Online information is available at: http://www.winterthur.org/?p=438. Tony Hyman maintains an informative website at: http://www.cigarhistory.info/Cigars/Welcome.html. Wonderful collections of tobacco-related ephemera are also held by institutions including: cigarette cards: W. Duke, Sons & Co., Digital Collections, Duke University: http://blogs.library.duke.edu/bitstreams/2014/10/24/collection-preview-w-duke-sons-co-cigarette-cards/; various collections and online exhibits: Digital AAS, American Antiquarian Society: http://www.americanantiquarian.org/digitalaas; photos, cabinet cards, tobacco cards, and photos of exotic dance from burlesque to clubs: Charles H. McCaghy Collection, Ohio State University: https://kb.osu.edu/dspace/handle/1811/47556; cigarette cards: New York Public Library Digital Collections: http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/cigarette-cards#/?tab=about; photography and the theater: Broadway Photographs, David S. Shields, University of South Carolina: http://broadway.cas.sc.edu/; trade cards: The Art of American Advertising, 1865–1910, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School: http://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/artadv/index.html ↵

- Fronia E. Wissman, “William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Nymphs and Satyr” in Sarah Lees, ed., Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Vol. 1 (Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute), 78. ↵

- “Some of the Art Attractions of New York” National Academy Notes including the Complete Catalogue of the Spring Exhibition. National Academy of Design, no. 5 (1885), 167. ↵

- “Notes” The Connoisseur 1, no. 2 (March 1887), 46–47. ↵

- Stephen Gillers, “A Tendency to Deprave and Corrupt: The Transformation of American Obscenity Law from Hicklin to Ulysses” Washington University Law Review 85, no. 2 (2007), 218. ↵

- For a recent overview of the evolution of obscenity law, see Whitney Strub, Obscenity Rules: Roth v. United States and the Long Struggle Over Sexual Expression (Wichita: University Press of Kansas, 2013). ↵

- The best source on cigar box labels is John Grossman, Labeling America: The Story of George Schlegel Lithographers, 1849–1971 (East Petersburg, PA: Fox Chapel Publishing, 2011). ↵

- Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986). ↵

- “Bather, also called Venus” (Louvre Museum, Paris), http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/bather-also-called-venus ↵

- Mark Hunter, “’Effroyable réalisme’: Wax, Femininity, and the Madness of Realist Fantasies” RACAR: revue d’art canadienne 33, nos. 1/2 (2008), 46. ↵

- “Our Art Censor” New York Evening Telegram (November 16, 1887), 1. ↵

- Jane Desmarais, “The model on the writers’ block: the model in fiction from Balzac to du Maurier” in Jane Desmarais, Martin Postle, and William Vaughan, eds., Model and Supermodel: The artist’s model in British art and culture (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2006), 54-55. ↵

- David S. Shields, “Carnal Glory? Nudity and the Fine and Performing Arts, 1890-1917” (Website Broadway Photographs), https://broadway.cas.sc.edu/content/carnal-glory-nudity-and-fine-and-performing-arts-1890-1917 ↵

- Jeanne Solensky to Amy Werbel, personal communication (March 11, 2016). ↵

- The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, Thirty-first Annual Report (New York, 1905), 23. ↵

- The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, Twenty-Seventh Annual Report (New York, 1901), 9–10. ↵

About the Author(s): Amy Werbel is Associate Professor of the History of Art at the Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York.