Andrew Wyeth and Birds of War

Introduction

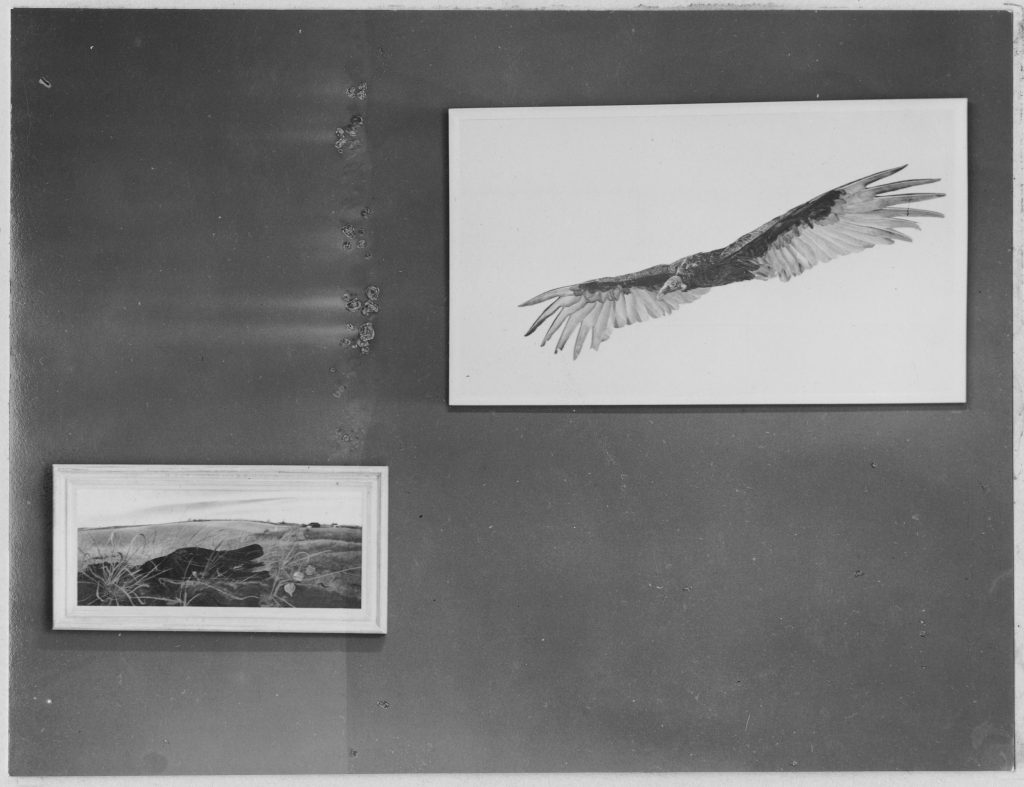

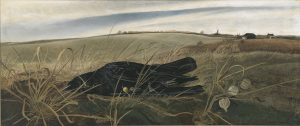

In 1943, the exhibition American Realists and Magic Realists at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York put Andrew Wyeth’s drawing of a turkey buzzard and his tempera Winter Fields into dialogue with each other (fig. 1). An installation photograph has Wyeth’s drawing of the vulture, with its wings spread, soaring high on the wall. Winter Fields, which features a worm’s eye view of a dead black crow, hangs below it and off to the side at a diagonal (fig. 2).1 In effect, the raptor appears to be swooping down, ready to feed on the carrion of the dead crow. With this hanging of the two works, the curators of the exhibition animate a narrative about death between the carnivore that seeks it out and the prey that lies lifeless and helpless on the ground. Staged in the middle of World War II, this visual enactment of avian foraging and death resonated inevitably with news from the battlefronts of the war.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt activated the military draft in September 1940, requiring all men between the ages of twenty-six and thirty-five to enlist, Andrew Wyeth registered, as did his older brother, Nat.2 Apparently Wyeth was, in the words of David Michaelis (biographer of Andrew Wyeth’s father, N. C. Wyeth), “gung ho to ship out for the Solomon Islands.”3 However, military recruiters assigned 4F status to Wyeth after a physical exam in February of 1943. Wyeth was born with what was then called Otto’s Pelvic Syndrome and walked with a limp.4 He turned down the opportunity to be a war correspondent in the US Navy’s Combat Artists Corps in April of 1942, and his medical condition led him to refuse as well a chance to cover the war for Life magazine. He responded to a query from Daniel Longwell, editor of Life, in a letter dated March 6, 1943:

I was delighted to receive your letter containing the remarkable opportunity for me, and I’d jump at the chance to go but less than a month ago my draft number came up and I took an advance Army physical and came through with a 4F! . . . I’ve been waiting just for a chance such as you offered and am terribly disappointed to have to reject it now that its [sic] come along. I feel I could do a real job with such a chance. I hope you will keep me in mind for the near future as I know it won’t be long before I am o.k. and ready for action.5

Wyeth’s optimism was misplaced: he never went to war as an artist correspondent or as a soldier.

Throughout the war, Wyeth stayed in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, in the Wyeth family compound where both he and his father, the famous illustrator, had studios. Although seemingly far removed from the battlefields of World War II, several of Andrew Wyeth’s landscapes from the early 1940s highlight the threat of violence and the presence of death in nature. As Wyeth himself stated: “You don’t have to paint tanks and guns to capture war. You should be able to paint it in a dead leaf falling from a tree.”6

In this essay I focus on how two temperas painted by Wyeth that feature birds are haunted by wartime killing and death. In Soaring of 1942 to 1950 (fig. 3)—for which the drawing of the buzzard exhibited at the MoMA show was a preparatory sketch—and Winter Fields, Wyeth experimented with radically different perspectives. Whereas the exhibited sketch delineates a frontal view of the vulture, the completed version of Soaring provides a perspective over the back of the bird in flight. Looking from on high or from flat on the ground in Winter Fields, the viewpoints in these pictures zero in on isolated birds in the landscape, stilled by the anticipation of the kill or by death. These paintings, both undertaken in 1942 just after the United States’ entrance into World War II, announced a new seriousness in Wyeth’s art by exploring avian vision both in theme and technique. In so doing, these paintings entered into a complex visual dialogue with those of Wyeth’s father and his brother-in-law, artist Peter Hurd, both of whom produced pictures explicitly on behalf of the war effort featuring birds or aerial viewpoints, respectively. Accordingly, this essay takes an extended foray into the wartime works of these other two artists, which set the immediate context for Wyeth’s paintings. Providing an alternative to N. C. Wyeth’s and Hurd’s more obviously patriotic and celebratory wartime pictures, Soaring and Winter Fields develop interspecies contact between birds and humans, enabling viewers to imaginatively empathize and experience death with the birds.7 It is precisely by exploring the possibilities and limits of avian vision that Wyeth’s paintings bring home the anxiety and tragedy of death at the battlefront. Soaring and Winter Fields point to the complex ways in which an exploration of the relationship between human and bird enables pictures of local nature to evoke the battlefront and to bring those on the home front into close and visceral proximity with death.

Soaring Like a Bird

In Soaring, begun in 1942, Wyeth took to the sky to adopt a bird’s-eye view of his surrounding landscape. In this large-scale painting, the viewer hovers with three turkey vultures above a lone house and barn isolated in a vast, empty landscape. The largest vulture, suspended just below the posited viewer, spreads its wings to span almost the entire width of the painting. It appears as a dark form outlined against the fallow winter fields below. The two other raptors that circle below, closing in on the farm, indicate the yawning distance between the viewer and the ground.

Viewers are close enough—disconcertingly so—to the largest vulture that they can scrutinize the distinctive markings of the bird: the ruffles of individual feathers; the long avian phalanges at the ends of its wings; the broad, feathered tail; and the wrinkled, bare red head that gives the name “turkey” to this species. Before undertaking this tempera, Wyeth began with extensive pencil sketches of an actual vulture. His commitment to objective analysis of the bird’s appearance aligned him with the tradition of ornithological illustration, following in the footsteps of famous nineteenth-century naturalist John James Audubon. Yet whereas Audubon would kill and then, using wires and threads, pose his specimens, Wyeth studied the live bird. His neighbor Karl Kuerner reported:

Buzzards always interested him, and one day he comes and says he has to have one so he can paint it. So Andy ’n me got the placenta from a newborn calf, put it in the pasture field back there, and set a ring of traps with it. And, by golly, we caught one. So there was Andy out there with that buzzard for days, painting. He wanted to paint it from above, and he had to see it.8

Vultures feed on carrion and combine keen vision with a discerning sense of smell to whiff the stench of death below. Curator Michael R. Taylor first pointed out a resonance between the bird’s-eye view in Soaring and aerial bombing in World War II:

Vultures are of course notable scavengers, and it may not be too much of a stretch to read a metaphorical meaning into Soaring, which was made during the darkest years of the Second World War, when civilian populations were menaced by dive-bombing airplanes. Suddenly the tiny homestead below seems threatened by the fearsome birds that are naturally drawn to the weak and the vulnerable.9

Developing this insight in a different direction, I argue that Wyeth explored the relationship between avian and human vision, revealing the multisensorial abilities of the bird, the limits of human vision, and ultimately the paradoxes of camouflage during World War II.

Wyeth had predecessors in striving for avian sight. Winslow Homer, an artist Wyeth greatly admired, began late in life to paint works such as The Fox Hunt of 1893 and Right and Left of 1909. In these works, Homer attempts to empathize with the animals he depicts by adopting their points of view: a fox being tracked by crows, two ducks as they are shot by a hunter.10 In our own day, this desire to experience the world like an animal has been taken to extremes. The veterinarian and writer Charles Foster recounts, in his book Being a Beast, his efforts to live like a badger, an otter, a fox, a red deer, and a swift, literally with his nose to the ground, chewing grass, or burrowing underground. Yet as Foster concedes:

Shamanic transformation possibly aside, there will always be a boundary between me and my animals. It’s as well to be honest about this and try to delineate it as accurately as possible. . . . The method, then, is simply to go as close to the frontier as possible and peer over it with whatever instruments are available. This is a process radically different from simply watching.11

Wyeth certainly tried to do more than passively study the live turkey vulture he had captured. In speaking about Soaring in an interview with George Plimpton and Donald Stewart, he recalls, “As a kid I used to lie on my back in the fields in March and April, when you get those turkey vultures here and find myself looking up and wondering how it would look looking down. I did the painting long before I went up in a plane.”12 On another occasion, he likened the experience of wearing a Halloween mask to imagining himself as his dog: “The feel of your face under a mask walking down a road in the moonlight. I love all that, because then I don’t exist anymore. To me it’s almost like getting inside of my hound, Rattler, and walking around the country looking at it through his eyes.”13 In Soaring, Wyeth—and by association the viewer—looks down as if he were himself a raptor onto fellow vultures, a farmhouse, and the distant hills.

Wyeth’s efforts to close the gap between human and bird put him at odds with two different visual traditions: at one extreme, the tradition of ornithology that treats the bird as a specimen, and, at the other extreme, the films from Disney Studios that anthropomorphize animals, including birds. The ornithologist studies the powerless—typically dead—bird in order to obtain knowledge that expands human understanding and asserts intellectual dominance over the animal kingdom. In Audubon’s illustration of a vulture of 1838, the bird appears perched on a branch against a white ground (fig. 4). Enabling close visual observation of the vulture’s distinctive markings, from the fine fluff on the neck to the elongated and sharp nails on the claws, the illustration maintains a clear boundary between the human and bird: the human can study this stilled creature with dispassion and presumably acquire the information necessary to recognize the buzzard in nature.

The Disney legacy stands in contrast. Beginning in the 1920s, Disney released silent short cartoons based on Grimms’ fairy tales, and in 1928 it launched Mickey Mouse in Steamboat Willie, its first cartoon with synchronized sound. A decade later, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs of 1937, the first full-length animated feature film by Disney, met with enormous success at the box office. Disney’s animated films consistently project human affects onto a variety of animals, including mice, pigs, and birds. The films often divide the animal kingdom into good and evil camps. Both the crow and vulture are aligned with evil in Snow White. For instance, a black crow, pet to the Evil Queen, perches on a skull to watch as she prepares her poison apple. In a later scene, the vultures, presumably whiffing the odor of death, track the Evil Queen through the forest to Snow White’s abode, and they follow her again when the seven dwarfs give chase. These large, evil birds contrast with the sweet little songbirds who encircle Snow White and exude goodness through their cute size and chirpy song. In short, the animated birds in Snow White, the bad along with the good, serve primarily as devices for representing recognizable human behavior and moral values.

Much like the ornithologist, Wyeth captured the vulture and studied it to enable precise visual representation. For all of his interest in the buzzard, he asserted human domination, undoubtedly causing the bird to suffer in captivity before setting it free. In the painting, however, he also used his empathetic imagination to recreate what a vulture might see from the air and to animate the vulture’s viewpoint for the human viewer. Crucially, avoiding Disney’s strategies of anthropomorphism, Wyeth implicitly presents this vision as avian and not human, exploring the divergence between the human and the animal much like Foster would later do. Although the viewer may adopt the vulture’s perspective in Soaring, able to discern the little white farmhouse embedded in the landscape below, she cannot see or smell the carrion that the circling birds obviously do. After all, the turkey buzzard feeds primarily on the dead flesh of animals owing to its keen senses of vision and smell that humans simply lack.

Tempera and Hyperprecision

Wyeth’s choice of medium also engages in avian vision. Even as Soaring implicitly points to the limits of the human capacity to see as a bird, Wyeth’s own painting technique as it developed during the war demonstrates an effort to outdo human vision, perhaps to see and paint like a bird, to see everything clearly and at once. His use of tempera helped Wyeth realize his commitment to “intensive perceptual acuity,” as photographer James Welling describes it: what painting conservator Joyce Hill Stoner labels “hyperprecision.”14 Wyeth’s artistic process entails an effort to see as carefully as possible by studying nature up close—indeed, by identifying with animals as much as humanly possible—and to recreate, with pencil and tempera, what he sees with as much painstaking clarity as possible.

Working with such extreme precision in tempera, as exemplified by both Soaring and Winter Fields, marked a radical shift in practice from his earlier work in watercolor. Wyeth attributed this shift toward more serious themes and techniques to his father’s untimely death in October 1945. He was deeply distressed by his father’s passing, saying later:

The loss of someone very close to you . . . does something that you can’t get any other way. His death shook me to my foundation. I think it lifted me out of being an “artist” into actually facing life, not doing caricatures of nature. It gave me a reason to paint. I wanted to get down to the real substance of life itself.15

When describing the change in emotional tenor in Winter, 1946, a tempera he completed after his father’s death, Wyeth disparaged his earlier watercolor landscapes: “When [my father] died, I was just a clever watercolorist—lots of swish and swash.”16 Many critics viewing Wyeth’s watercolors in the early 1940s did indeed describe them with words such as “ebullient.” An anonymous article devoted to “one of America’s youngest and most talented artists” in American Artist in 1942 opened with lavish praise for the exuberance of Wyeth’s watercolors: “They dance, they sparkle, they are full of gusto with which this young artist embraces nature and life itself. They are likeable.”17

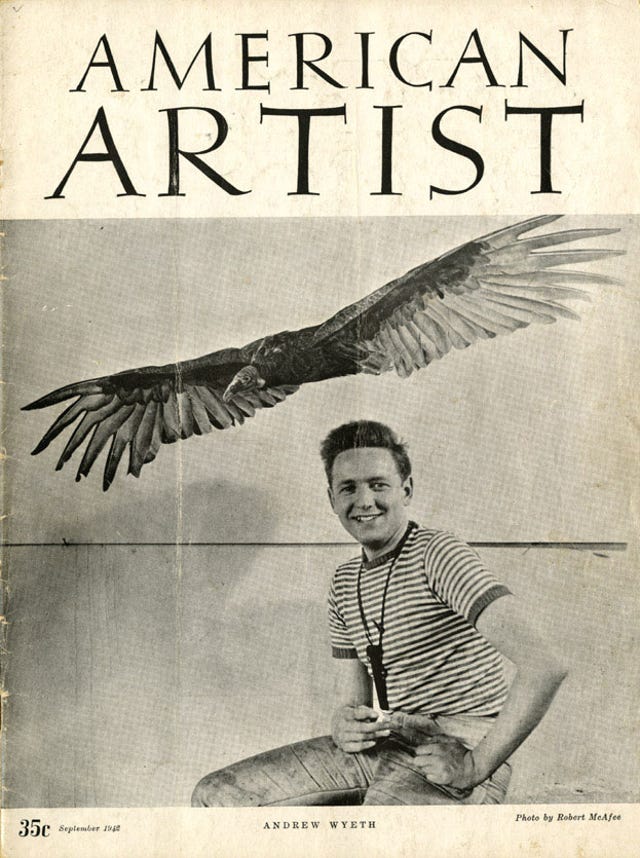

But, in fact, the change in tone in Wyeth’s art predates his father’s death, appearing first in temperas he began painting following the United States’ entrance into World War II. Wyeth’s pencil studies of the turkey vulture in 1942, together with the tempera Soaring, mark the beginnings of a shift in medium, from spirited and quick brushwork to hyperprecision, from lighthearted seascapes to serious scrutiny of nature. On the September 1942 cover of American Artist (the issue containing the article praising his lively and likeable watercolors), Wyeth is photographed seated on a stool, grinning at the camera, in front of one of his vulture drawings, so that the enormous bird appears to be hovering above him (fig. 5). Despite Wyeth’s cheerful demeanor in the portrait, the swooping vulture hints at the darker side of nature emerging just then in Wyeth’s temperas.

This drawing of a turkey vulture was included in American Realists and Magic Realists, an exhibition that further included two ink drawings and five temperas by Wyeth, Winter Fields among them. One of the other tempera works included in the show, Frog Hunters in the Brandywine Valley of 1941, also focuses on the perspective of an animal, in this case presumably a frog, hidden among the foliage at the edge of a pond and observing two men in the distance, one of whom is armed with a rifle. Two years later, Wyeth depicted another view of a hunter, this time from the perspective of a bird. The Hunter of 1943 invites the viewer to perch on a branch of the giant buttonwood tree filling the foreground and to look down on a hunter whose red cap makes him startlingly visible among the otherwise subdued russet tones of the fall landscape (fig. 6). Wyeth’s thematic insistence on taking up the perspectives of animals, particularly in life and death situations, stands in sharp contrast to Audubon’s oil painting Ivory-billed Woodpeckers, also included in American Realists and Magic Realists, in which three birds peck away at a tree, seemingly oblivious to the fact that they are being observed (fig. 7).18 In Audubon’s piece, the viewer remains firmly human, looking in from outside of the animal’s sphere.

Although American Realists and Magic Realists included precedents from the nineteenth century, the exhibition focused primarily on works by younger American artists championed by curators Dorothy C. Miller and Lincoln Kirstein as exemplifying “sharp focus and precise representation.”19 In Wyeth’s case, this new predilection for precision in tempera led critics of the MoMA exhibition, as well as of Wyeth’s solo show at the MacBeth Gallery in New York that same year, to recognize and applaud a new seriousness in his art. Later in 1947, when Wyeth received the Award of Merit from the Academy of Arts and Letters, a critic for Newsweek commented: “By 1943, he was painting with a clarity which the Museum of Modern Art endorsed with the title ‘magic realism.’ He had discovered angles and aspects which gave meaningful overtones to subjects like a frozen bird in a winter field or a close-up of sycamore bark.”20

This shift in seriousness in Wyeth’s case was motivated personally by a desire to be an artist rather than an illustrator, a distinction encouraged by both his father and his wife. N. C. Wyeth had always urged his son to become what he himself was not: a serious artist. Andrew Wyeth paid tribute to his artistic training under his father in the statement included in the catalogue for American Realists and Magic Realists:

This training consisted of incessant drilling in drawing and construction from the cast, from life and from the landscape, “and so,” my father often said, “to understand nature objectively and thus be soundly prepared for the later excursion into subjective moods and the high spirit of personal and emotional expression.”21

With his mature works, Wyeth strove to depict nature with care and craft, from pencil sketches to tempera, using nuanced brushwork and subdued colors. As the artist himself commented, his father created everything from imagination not from nature. Andrew Wyeth also pointed to his use of color as a marked difference between his father’s illustrations and his own paintings, saying that people in the commercial field pushed his father to heighten his colors.22 Endowing his scenes with a gravitas lacking in the bright, swashbuckling illustrations of his father delineated a clear difference in professional ambition and practice between father and son.

The shift in medium and tone marked the emergence of an artistic ambition that was strongly encouraged by Andrew’s wife, Betsy, whom he married in 1940 and who, in October 1942, took over the management of her husband’s career from the elder Wyeth.23 Betsy Wyeth not only dealt with finances; she also pushed Wyeth to pursue “serious art” rather than commercial illustration. Encouragement in this direction entailed both praising her husband for his ambitious paintings and discouraging him from accepting commercial assignments for the sake of earning money. For example, after Wyeth completed The Hunter for the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in October 1943, the magazine offered him the opportunity to do ten more covers. Betsy was adamant that to accept would lead to eventual artistic degradation, and he would “be nothing but Norman Rockwell for the rest of [his] life.”24 What she left unsaid here is that he risked becoming a commercial illustrator like his father.

A commitment to precision in tempera, encouraged by an ambition to be something other than a commercial illustrator, put Wyeth in step with certain trends in the art world, as acknowledged by his inclusion in the exhibition at MoMA. Combined with a thematic interest in death and killing, this new turn to hyperprecision in tempera also resulted in works that, as we will see, resonated with the war.

The Wyeths and War Illustration

Richard Meryman, Wyeth’s biographer, reports that when N. C. Wyeth saw Soaring, he told his son, “Andy that doesn’t work. That’s not a painting.”25 Andrew Wyeth set the painting aside and did not complete it until 1950, when Kirstein encouraged him to include it in a show at the MacBeth Gallery in New York. Although there is no further written account of N. C. Wyeth’s reaction to Soaring, the father’s condemnation was likely motivated by the son’s choice of a bird associated with death rather than his own more inspiring collection of bird images begun in 1942, the same year Andrew Wyeth began his picture.

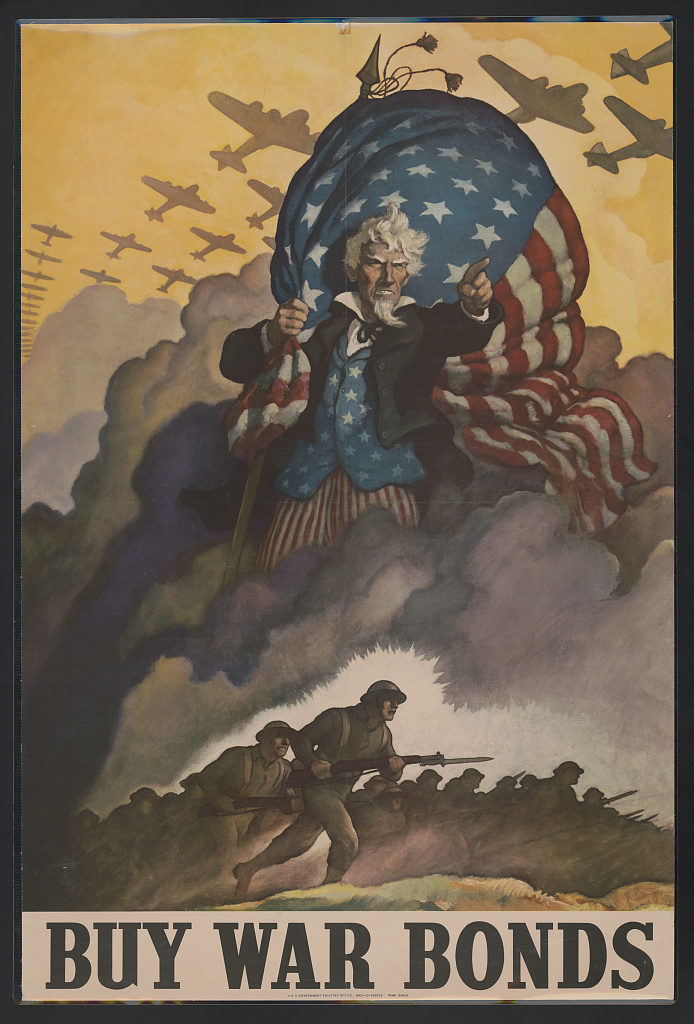

With the entrance of the United States into World War II, N. C. Wyeth started designing stirring illustrations of airborne flags and eagles for calendars and war bonds. In his poster Uncle Sam (also known as Buy War Bonds), published for the Treasury Department in spring 1942, the massive figure of Uncle Sam hovers majestically in the sky (fig. 8). Winning a special citation for its design in 1943 and singled out as one of the most popular posters issued at the time,26 the image pictures a determined Uncle Sam gripping an enormous American flag, which sweeps over his shoulders and waves above ominous clouds. With a squadron of fighter planes flying overhead in the sunlit sky, he points the way forward, guiding the soldiers on the ground below him.

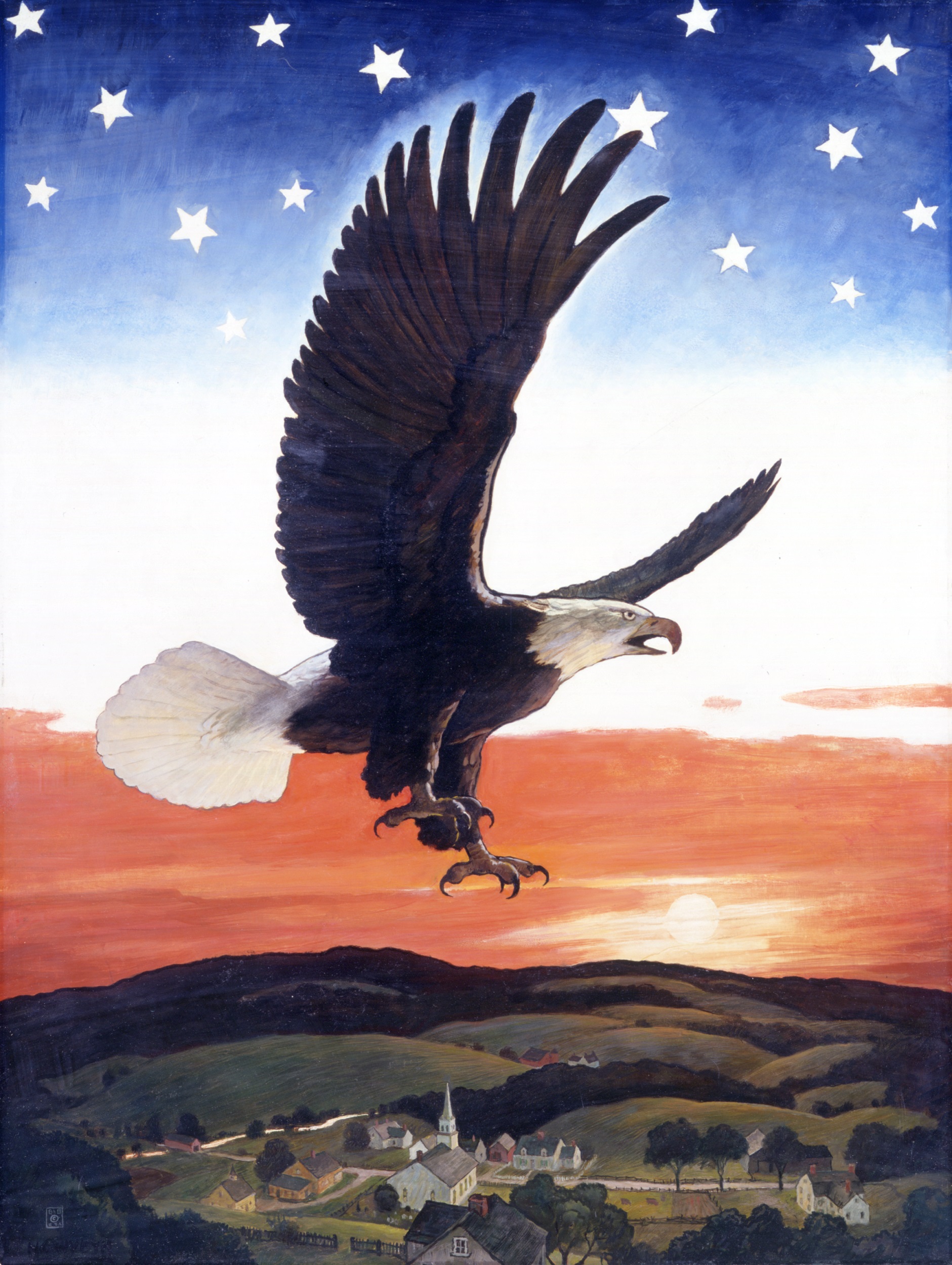

This horizontally split format appears in a number of N. C. Wyeth’s patriotic posters and paintings about World War II. Consider Our Emblem of 1942, which portrays an eagle soaring above a stereotypical New England village (fig. 9). This oil painting was commissioned by the publishing house Brown and Bigelow, which used it as a calendar illustration. As Wyeth specialist Christine Podmaniczky notes, N. C. Wyeth received explicit instructions for the composition from his client:

At the bottom . . . a small village with the red of the sunrise that will suggest the red stripe in our flag. This tone will gradually fade into a pure white . . . into the lightest tone of blue, gradually going into the deeper values of the same color to the top of the composition, and the blues will be studded with the stars of the night. The American Eagle is to be superimposed over the blue. . . . A long time ago, you illustrated a book of American patriotic poems by Brander Mathew [sic]. Our client has seen this book, and he would like you to paint the eagle as you did for the frontispiece of this book.27

For Our Emblem, N. C. Wyeth reversed the image of the eagle he had rendered earlier for the endpapers of Brander Matthew’s Poems of American Patriotism, while also enlarging it in relation to the overall image.28 The bird’s size in the later work, together with its determined glare and open beak screeching a warning, strengthen the eagle’s symbolic value as a protective avatar over an idealized New England village, complete with church steeple. In Old Glory Symbol of Liberty, another poster produced in 1942, N. C. Wyeth pictures a soaring eagle from below so that it appears outlined against white clouds and hovering above an American flag rising out of dark clouds. The recurring motif of the eagle in these wartime posters embodies an inspirational patriotic sentiment.

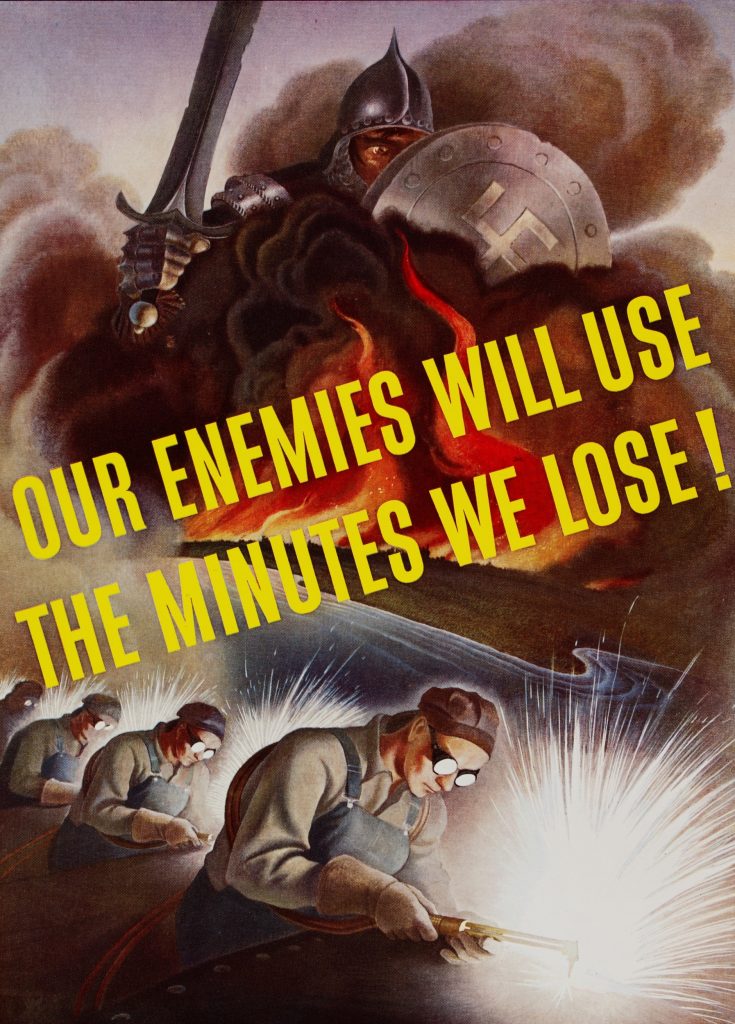

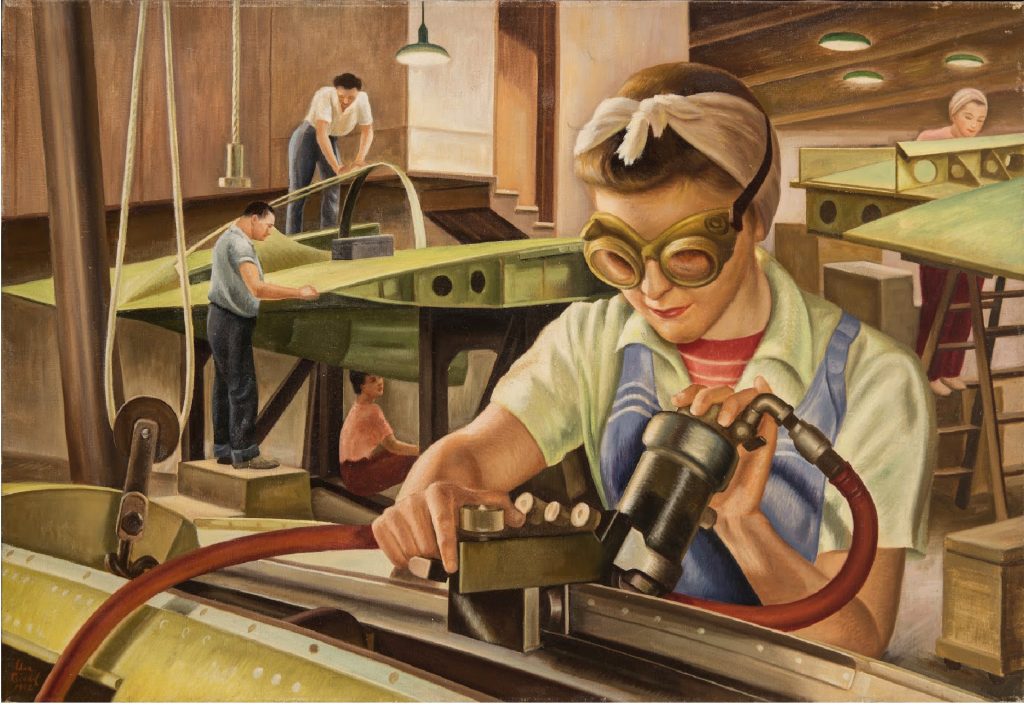

Andrew Wyeth designed only one war bond poster. In it, he mimicked his father’s split-level design and patriotic fervor, although the message is as dark and menacing in the upper half as it is exhorting below. In Our Enemies Will Use the Minutes We Lose!, produced for Abbott Laboratories in 1942, a massive Teutonic knight, akin to the sort seen in N. C. Wyeth’s illustrations of chivalric knights from Sidney Lanier’s The Boy’s King Arthur of 1917, holds a sword in one hand and a shield emblazoned with a swastika in the other (fig. 10). Looming over the landscape, this horseman of the Apocalypse drives before him orange and yellow flames that threaten to engulf the town appearing on the horizon. Wyeth pictures an imminent threat to the United States from enemies abroad, along with the response from a phalanx of industrious welders seen in the bottom half of the poster. The workers do not confront the knight directly but rather focus on their task of building arms for others who will take them into battle. The welders, presumably American, are possibly women who have, like Rosie the Riveter, entered the industrial workforce during the war.

The bodies of Wyeth’s welders are notably androgynous, unlike, say, Edna Reindel’s paintings of women at work in a Lockheed aircraft plant and a California shipyard, published in Life magazine in June 1944 (fig. 11).29 It was apparently important to Reindel to emphasize the femininity of the women she depicted. Their visors are perched on their heads to reveal individualized faces, and their overalls cling to the curves of their bodies. In the captions, Reindel gives names to the women and highlights their particular skills, including manipulating drills, riveting machines, and welding torches. Even those wearing protective helmets and overalls are identified by their gender. In contrast, Wyeth depicts the workers as androgynous robots, covered in gloves, goggles, and caps so that they appear as interchangeable cogs in an assembly line. His figures exemplify Fordist labor and the efficient production of military equipment that promised to defeat the Nazis. Yet for Andrew Wyeth, unlike for his father, this illustration remained an exception to his main focus on less didactic painting.

In 1942, as his father began picturing eagles literally caught up in battle, Andrew Wyeth’s Soaring avoided any obvious polemic, dwelling on a raptor of death rather than an eagle of victory. This bird was one known for feeding on death rather than a beloved symbol of country, patriotism, and nationalism. Moreover, the care and attention Wyeth employed in his tempera was a far cry from the rapid and efficient manufacture of military equipment on the assembly line by welders or the prescriptive production of posters exemplified by his illustrator father.

Peter Hurd and Aerial Vision

Andrew Wyeth’s rendition of the vulture’s view of the Pennsylvania landscape also entered into dialogue with the work of his brother-in-law Peter Hurd. Hurd, who apprenticed in 1924 with his father-in-law, N. C. Wyeth, had a special relationship with Andrew, teaching him how to paint in tempera in 1936.30 Returning the favor, Wyeth instructed Hurd in the use of watercolors in 1943, so that Hurd could make quick sketches in his role as a war correspondent. Hurd had two assignments as a war correspondent for Life magazine. The first took him in 1942 to England with the 8th US Army Air Force. On his second job in 1944, he toured around the world with the Air Transport Command. During his travels, he wrote to both N. C. and Andrew Wyeth, telling them about the geography and people of the various countries he visited. Paintings from both of Hurd’s assignments were reproduced in Life magazine, and N. C. and Andrew Wyeth alike complimented Hurd on these works.31

On his first mission embedded with the 8th US Army Air Force, Hurd documented its operational activities. As he recorded in his journal in July 1942, one of his greatest experiences was accompanying pilots on a cross-country training mission when, at one point, Hurd took the bombardier’s seat in the nose of the plane. During or immediately after the flight, he completed five small watercolors.32 Versions of three of these were reproduced in Life magazine a year later, accompanying an article featuring the Flying Fortress planes as powerful precision bombers.33 In the first image, the viewer inhabits the post of waist gunner (located in the middle of the plane) and looks over fields as if seeking a target through the bombsight. In the second, the viewer assumes the tail gunner’s perspective as he looks back at two columns of black smoke rising to the left of his sight, as if after a bombing raid. In the third, the viewer takes the perspective of the navigator, comparing the view on a map to that from the window. The Life article extols the Flying Fortress as a means to attack military targets with accuracy while avoiding civilian casualties (although during the war, these bombers would also be purposefully used against noncombatants and were not as precise as the military claimed). The article in Life champions the 8th US Army Air Force as accomplishing “miracles” with such advanced aircraft.34 Hurd, highlighting the sharpness of vision attributed to the bombardier, renders the bombsights, machine-gun posts, maps, and aerial views with detail.

In his watercolors of the landscape from the airmen’s perspective, Hurd evokes the technological means by which the military made terrain visible for the purpose of reconnaissance, tactical bombing, and the assessment of damage. As art historian Jason Weems argues, the aerial view had already emerged in the 1930s as a means to make legible a rationalized Midwestern landscape, which had been transformed into a homogeneous grid for the purpose of industrial agriculture.35 In Hurd’s pictures, the viewer sees how the military adopted tools such as the aerial camera, scope, map, compass, and ruler to measure and navigate the landscape in order to bomb it.36

Images of airmen and their airplanes captured the imagination of Americans during the war, appearing in advertisements, war bonds, and even on stamps. War movies produced during the 1940s often featured fearless pilots, enabling audiences at home to share an aerial perspective of the landscape during battle. The British documentary Target for Tonight from 1941 portrays, as stated in the film’s publicity materials, “the authentic story of a bombing raid [by the Royal Air Force] on Germany . . . how it is planned and how it is executed.”37 The film won an honorary Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1942 and inspired a US version in 1944, titled Target for Today. The original British film opens with a bomber flying overhead and dropping a bundle to be retrieved on the ground. It turns out that the package contains photographic film, which is delivered to the photography section of the bombers’ command post. Using a magnifying glass and comparing the new batch of photographs to aerial photographs taken three months earlier, the squadron leader discovers enemy oil storage tanks located at Freihausen on the Rhine. A clear chain of military command, combined with a detailed consideration of maps, weather, and winds, demonstrates all of the rational organization, analysis, and planning involved before executing a bombing raid.

Yet these films also hint at the limits of aerial vision. Once airborne, the pilots have difficulty seeing their target because of nightfall, the unpredictability of the weather, and the flashes of light and smoke from the bombs they drop, as well as the confusion caused by enemy flak. On the return home, thickening fog also disrupts visibility. Target for Today heroizes the brave pilots, making viewers sympathetic to the difficulty of their assignments, and acknowledges the ways in which unforeseeable factors can obfuscate omniscient perspective.

The movie highlights the complexities of aerial vision. On the one hand, by studying aerial photographs, the squadron leader sees through the enemy’s camouflage, while, on the other hand, human impediments and natural causes make the hidden storage tanks hard for the pilots to see and destroy. Indeed, new practices of camouflage developed during World War II exemplify the military possibilities offered by aerial vision as well as its limits. Most texts published on military camouflage acknowledge the claim made by Herbert Friedmann in 1942 that the “modern study of concealment and disguise in nature may be said to date from the work of American artist-naturalist Abbott Thayer.”38 In his book Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom: An Exposition of the Laws of Disguise through Color and Pattern (1909), cowritten with his son, Gerald, Thayer relied overwhelmingly on the example of birds to demonstrate how natural color patterns interacting with surrounding light could make birds disappear into the background, concealing them from predators. Starting in World War I, the military hired artists to design camouflage inspired by the example of natural concealment investigated by Thayer. With the increased use of airplanes in World War II, however, camouflage became a much more complicated practice, no longer confined to hiding targets from ground-level view.

In response to the increased visibility of the landscape as seen through the bombsight of a plane, a new science of camouflage developed to anticipate aerial raids and to hide potential targets from the bombardier’s view. An interdisciplinary group of experts in fields including art, architecture, design, and engineering collaborated to invent new practices of camouflage that would hide military or civilian targets from airplanes flying quickly under changing conditions of light and weather. The goal was to design camouflage effective at distracting and disorienting the enemy flying overhead rather than completely hiding a target from view. At the same time, pilots and bombardiers had to be trained to see through the enemy’s disguises and to master aerial reconnaissance in order to detect camouflaged targets.39

Whereas Hurd’s illustrations suggest that the technology of aerial vision—as framed by the window, bombsight, eye of the bombardier, or map—had the ability to make the landscape fully visible to the bombardier, Soaring points to the limits of the human eye by comparing and differentiating human and avian vision. Wyeth provides the domestic counterpart to the pilot’s perspective presented by Hurd. Indeed, Soaring offers an ironic twist on the avian origins of the practice of military camouflage. In this work, Wyeth reverses Thayer’s proposition by having birds exemplify the predator’s perspective, superior to human efforts to see through disguise. The painting invites the viewer to partially experience the superior perception of the vulture targeting its prey through a combination of sight and smell. Yet the raptors hover and circle around dead carrion that they can presumably smell and that we, as human viewers, cannot see. This interspecies contact does not presume the superiority of human vision, which can be foiled by the unpredictability of nature or human cunning in camouflage. Rather, it forces human viewers to recognize their own perceptual constraints.

Winter Fields and Dead Soldiers

Winter Fields, another tempera painted by Wyeth in 1942 and included in the American Realism and Magic Realism exhibition, likewise features a bird. However, in Winter Fields, Wyeth’s perspective, rather than flying high above the earth, is lowered to the ground, from where he and the viewer observe another scavenger, the black crow, from a proximate position. Known for its intelligence, the crow has a more catholic appetite than the vulture and eats almost anything, from insects to human garbage. Wyeth’s crow, however, lies dead on the ground.

Viewing the crow from such a close vantage, the viewer can see the stiff bird’s dark, feathery underside, touched by highlights of white, and its wizened claws. The corpse is framed by wisps of brown grass and lantern plants, dry and almost transparent. Beyond is a field that has been harvested, a barn and house on the horizon, a human world seemingly indifferent to the dead bird, to the inexorable cycle of nature, and even to us, the viewers.40 If anything, this bird is now the carrion awaiting a turkey vulture swooping down from above. Even as the crow’s distinctive features are rendered with an ornithologist’s precision, the bird’s placement allows viewers to experience death up close and to feel vulnerable themselves to the potential attack from above.

Curator Patricia Junker points to the allegorical aspect of Wyeth’s point of view in this picture: “Winter Fields is a shocking, all-too-close, worm’s-eye view of a dead crow, frozen stiff in a field drained of color—fallen like so many soldiers in the killing fields of any war.”41 Indeed, the dead crow resonates with a history of images of war dead. Wyeth had been familiar with such images since childhood, when he first saw photographs of dead soldiers from World War I in his father’s studio. As Podmaniczky explains:

N. C. Wyeth’s studio had a vast archive of printed resources that presented all aspects of the war. He had preserved approximately three hundred fifty rotogravure pages from the New York Times, New York Sun, and Philadelphia Public Ledger dating from the [World War I] years. . . . Perhaps most important for its effect on an impressionable imagination was The World War through the Stereoscope, a set of three hundred stereopticon views of the war. . . . The sharply focused images, viewed in three dimensions through a handheld stereoscope, presented a record of the war otherwise available only in newsreels.42

Although photographs of the war dead were banned during World War I, they were included in The World War through the Stereoscope series, released in 1923. Likewise, the movie The Big Parade, King Vidor’s silent film of 1925, includes scenes of trench warfare, with dead and wounded soldiers. Andrew Wyeth, whom N. C. Wyeth introduced to the film when his son was only eight years old, developed a particular attachment to it, eventually owning a copy that he would screen regularly throughout his life.43

The dark shape of the crow lying on the ground in Winter Fields also evokes, further back in the American history of combat, one of the most famous photographs from the Civil War: Timothy O’Sullivan’s Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, July, 1863. As one of the first photographs of American war casualties, O’Sullivan’s image presents dead bodies strewn across the landscape from a slightly above-ground level. Although the scene blurs in the distance, the foremost soldier is clearly visible, lying spread on the ground, his body bloated, his skin blackened, his fingers stiffened, surrounded by strands of grass rigidly sticking up from the ground.

At the time Wyeth completed Winter Fields, the American government still censored photographs of the dead on the battlefields of World War II. One year later, this injunction was lifted in order to rally the public to support the war abroad. Initially, President Roosevelt and his advisors had feared that military setbacks would contribute to diminishing American commitment to fighting the war. Starting in 1943, however, they worried that publicizing only victories would distort the expectations and perceptions of the American public. As George Roeder argues in The Censored War, advisors to the president proposed that the government release harsher photographs, emphasizing the realities of war, to prepare the public for greater casualties. As Roeder points out, this policy soon manifested itself when, in May 1943, Newsweek printed a photograph of an American soldier badly injured in the Pacific campaign. The editors announced in its pages that “to harden home-front morale, the military services have adopted a new policy of letting civilians see photographically what warfare does to men who fight.”44 Life, the most widely read photo-magazine of the day, released its first photograph of Americans killed in the war in September 1943.

Winter Fields would have gained a new layer of meaning with the release of photographs of war dead from the battlefronts of World War II. However, the painting does not adopt the usual perspective of the war photographer documenting death during the world wars. Such war images overwhelmingly preserve a distinction between the living and the dead, as photographers typically stand above and look down on the corpses. Wyeth’s painting places us much closer to death, in the position of the lifeless crow itself or perhaps some distasteful creature such as a vulture lowering itself to the level of its meal, or even an insect come to feast on dead flesh. Perhaps Hurd could have sensed some resonance with his own experience of war, once back on the ground, when he wrote Wyeth two years later in 1944 about his “times of terrific horror” experienced from his own lowly perspective:

One day in the middle of May, after a jeep trip to the front from Naples I found myself smack bang in the middle of a battle—a frontal assault by tanks and Infantry [sic]—my first (and I hope last!) battle. If we had an hour together now I think I could make you feel how it was to be there—to see it from my view: the view from the eye of a scared worm.45

Famously, Ernie Pyle’s syndicated daily columns from the battlefront, which appeared in newspapers around the country, delivered a “worm’s eye” or “foxhole” view from the perspective of the soldier, rather than from a broad overview of military strategy or even a bomber’s elevated outlook. Pyle himself commented “that after the worm’s eye view I got in the front lines during a big portion of the fight, it was hard to see anything from the big angle.”46 Wyeth, it would seem, experimented at home with both the bird’s-eye and worm’s-eye views of death.

Conclusion

The curatorial choice to juxtapose Wyeth’s drawing of the turkey buzzard in flight against Winter Fields in American Realism and Magic Realism generated a vivid story about death in nature. The exhibition, which opened only a few months before the American government decided to release explicit photographs of dead American soldiers, enabled viewers to observe and imagine an interactive scenario in which the vulture swoops down to the landscape in Winter Fields to pick at the dead body of the crow. The extremely divergent viewpoints of Winter Fields and the Soaring study—together with their physical juxtaposition in the show—asks viewers to consider what it might feel like to be the potential victim of the hovering vulture or to be the hungry raptor searching below for carrion. It insists on making death a visceral experience from both perspectives.

It is difficult to make sense of the melancholy of Wyeth’s wartime works without considering the news from the battlefront that filled the newspapers every day and being aware of the propagandistic and journalistic images of the war produced by N. C. Wyeth and Hurd. Forced to remain at home, Andrew Wyeth, in dialogue with both his father and his brother-in-law about the visual and emotional experience of war, offers a complex and poignant view of death through his images of nature and landscape on the home front. His paintings enable both panoramic and intimate views of death. Moreover, they ask viewers to dwell empathetically on the liminal zones between humans and animals, between the living and the dead, and between combatants and noncombatants—all barriers that can never be fully traversed. Such empathetic imagining points to the limits of human vision while also enabling human viewers to expand their capacity for experiencing death and feeling vulnerable. Undercutting humankind’s capacity and confidence to stand and to fully dominate the landscape, these temperas raise questions about the human command over nature and the costs of war.

Cite this article: Cécile Whiting, “Andrew Wyeth and Birds of War,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12367.

PDF: Whiting, Andrew Wyeth and Birds of War

Notes

I am very grateful for the invitations I received from colleagues to present an earlier version of this paper: Elizabeth Cropper at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, David Peters Corbett at The Courtauld Institute, and Amelia Goerlitz at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. At each venue, I received very provocative comments that caused me to rethink my argument. Special thanks go to Jacqueline Francis, Jim Herbert, John Ott, and Caroline Riley as well as the curatorial staff and librarians at the Brandywine Conservancy and Museum of Art. I also thank the anonymous reviewers for Panorama for their important insights.

- The catalogue reproduces the two pictures, one above the other, on the same page, producing a similar, albeit less powerful, effect. ↵

- David Michaelis reports, “Andy registered with his local draft board in Maine. He was twenty-four and planned to wait until called, then enter the army as a private.” Nat was indispensable at DuPont during the war, where he “invented automated machinery that produced detonators for antiaircraft guns.” N. C. Wyeth: A Biography (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1998), 375, 381. ↵

- Michaelis, N. C. Wyeth, 400. Patricia Junker points out that Andrew Wyeth turned down the chance to be a war correspondent in April 1942; see her “Marking Time, 1917–1949,” in Andrew Wyeth in Retrospect, ed. Patricia Junker (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 20. ↵

- N. C. Wyeth to Henriette Wyeth (Andrew Wyeth’s sister), February 4, 1943; reprinted in Betsy James Wyeth, ed., The Wyeths: The Letters of N. C. Wyeth, 1901–1945 (Boston: Gambit, 1971), 820. ↵

- Wyeth to Daniel Longwell, March 6, 1943, Daniel Longwell Papers, 1920–74, box 7, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. ↵

- Junker, “Marking Time,” 17. ↵

- The central texts in animal studies that have informed my thinking in this essay include Rosi Braidotti, “Animals, Anomalies, and Inorganic Others,” PMLA 124, no. 2 (March 2009): 526–32; Charles Foster, Being a Beast: Adventures Across the Species Divide (New York: Henry Holt, 2016); and Elizabeth Sutton, Art, Animals, and Experience: Relationships to Canines and the Natural World (New York: Routledge, 2017). ↵

- Gene Logsdon, Wyeth People: A Portrait of Andrew Wyeth as He is Seen by His Friends and Neighbors (Garden City: Doubleday, 1971), 34–35. ↵

- Michael R. Taylor, “Between Realism and Surrealism: The Early Work of Andrew Wyeth,” in Andrew Wyeth: Memory and Magic, ed. Anne Classen Knutson (New York: Rizzoli, 2006), 32. Since 2006, when Taylor compared the vultures in Wyeth’s Soaring to “dive-bombing warplanes,” a number of scholars have discussed how Wyeth expressed wartime anxiety in his paintings of the 1940s. See Henry Adams, “Andrew Wyeth at the Movies: The Story of an Obsession,” in Junker, Andrew Wyeth in Retrospect, 48–63; Thomas Denenberg, “Soaring: Art and Anxiety in Mid-Century America,” in Wyeth Vertigo, ed. Thomas Denenberg (Lebanon: University Press of New England, 2013) and published as well in AFAnews.com, http://www.afanews.com/articles/item/1975-soaring-art-and-anxiety-in-mid-century-america#.X0fUZGdKitk; Junker, “Marking Time,” 10–29; Alexander Nemerov, “The Glitter of Night Hauling: Andrew Wyeth in the 1940s,” in Rethinking Andrew Wyeth, ed. David Cateforis (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 101–11; and Christine B. Podmaniczky, “Andrew Wyeth’s War Memory: The Enduring Influence of N. C. Wyeth and World War I,” in Junker, Andrew Wyeth In Retrospect, 30–47. ↵

- Rachel Z. DeLue discusses Winslow Homer’s identification with fox and ducks in her introduction to Picturing, ed. Rachel Z. DeLue (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 15–16. Annie Ronan explores the interspecies dynamic at work in Homer’s pictures that depict deer in “Capturing Cruelty: Camera Hunting, Water Killing, and Winslow Homer’s Adirondack Deer,” American Art 31 (Fall 2017): 52–79. ↵

- Foster, Being a Beast, 13. ↵

- “Andrew Wyeth: An Interview with George Plimpton and Donald Stewart,” Horizon (September 1961): 99–100. ↵

- Richard Meryman, “Andrew Wyeth,” Life, May 14, 1965, 108. ↵

- James Welling, “The Wyeth Foundation for American Art and CASVA,” in National Gallery of Art Bulletin (Spring 2015), 43; and Joyce Stoner, “The Messages in Andrew Wyeth’s Medium,” in Cateforis, Rethinking Andrew Wyeth, 87. ↵

- Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Spoken Self Portrait (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art with D.A.P., 2013), 99. N. C. Wyeth’s untimely death occurred in October 1945 when he, together with his grandson, were sitting in a car that stalled on railroad tracks and was hit by an oncoming train, killing them both. ↵

- Meryman, “Andrew Wyeth,” 108. ↵

- “Andrew Wyeth: One of America’s Youngest and Most Talented Painters,” American Artist 6 (September 1942): 18. ↵

- American Realists and Magic Realists attributes the oil to Audubon. In actuality, it was painted by Joseph Bartholomew Kidd at Audubon’s request. Kidd copied a watercolor of the woodpeckers by Audubon and added the background landscape. For information on Kidd and this painting, see “Ivory-Billed Woodpeckers,” Metropolitan Museum of Art website, accessed October 6, 2021, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/11332. ↵

- Dorothy Miller, foreword to American Realists and Magic Realists, ed. Dorothy Miller and Alfred Barr (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1943), 5. Emphasis original. ↵

- “An Early Wyeth,” Newsweek, April 21, 1947, 94. See also M. R., “Andrew Wyeth’s New Maturity,” Art Digest, November 1, 1943, 9. ↵

- Miller and Barr, American Realists and Magic Realists, 58. ↵

- E. P. Richardson, “Portrait: Andrew Wyeth,” Atlantic 213, no. 6 (June 1964): 64, 68. ↵

- Michaelis, N. C. Wyeth, 391. ↵

- Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), 181. ↵

- Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life, 160. ↵

- Christine B. Podmaniczky, N. C. Wyeth: Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, 2 vols. (Wilmington: Wyeth Foundation for American Art, 2008), 2:694. ↵

- Podmaniczky, N. C. Wyeth, 2:688–89. ↵

- For more on Wyeth’s illustrations for Matthews’s book, see Michael K. Komanecky, N. C. Wyeth: Poems of American Patriotism (Rockland, ME: Farnsworth Art Museum, 2018). The original painting for the endpapers is illustrated on p. 92. ↵

- “Women at War: Edna Reindel Paints Them at Work in U.S. Shipyards and Plane Plants,” Life, June 5, 1944, 74–78. ↵

- Junker discusses Hurd and Wyeth attending a demonstration of tempera painting in the early Renaissance manner at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1938 (“Marking Time,” 14). Wyeth himself wrote: “Tempera is something with which I build—like building in great layers the way the earth was itself built. Tempera is not the medium for swiftness.” Wyeth quoted in Thomas Hoving, introduction to Andrew Wyeth: Autobiography (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1995), 11. ↵

- Hurd seemed particularly pleased when he wrote to his wife in the summer of 1945 that he had received “a nice letter from Andy telling of liking my spread in Life” (Peter Hurd to Henriette Wyeth, summer 1945; quoted in Robert Metzger, My Land Is the Southwest: Peter Hurd Letters and Journals (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1983), 345. Wyeth also praised Hurd’s pictures in Life: “I think the Pete Hurd layout was swell. He is a great guy and fine painter,” Andrew Wyeth to Daniel Longwell, March 1943, Longwell Papers, 1920–74, box 7, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. ↵

- Peter Hurd, journal entry dated July 26, 1942; quoted in Metzger, My Land Is the Southwest, 281. ↵

- “8th U.S. Army Air Force: Hurd Paints Early Days of Operations Now One Year Old,” Life magazine, July 26, 1943; available online at https://books.google.com/books?id=R1AEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA58&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false. ↵

- “8th U.S. Army Air Force: Peter Hurd Paints Early Days of Operations Now One Year Old,” Life, July 26, 1943, 60. ↵

- Jason Weems, Barnstorming the Prairies: How Aerial Vision Shaped the Midwest (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), ix. ↵

- Aerial photographs, many of which were published in the print media, were used as a basis for creating maps as well as three-dimensional models of cities in military war rooms. See Jean-Louis Cohen, Architecture in Uniform: Designing and Building for the Second World War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 322. ↵

- Bosley Crowther, “Target for Tonight, a Fine Fact Film About the R.A.F. at the Globe,” New York Times, October 18, 1941, 22. ↵

- Herbert Friedmann, The Natural-History Background of Camouflage, Smithsonian Institution War Background Studies 5 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1942), 3. ↵

- Some excellent secondary sources with helpful discussions on camouflage include John Blakinger, Gyorgy Kepes: Undreaming the Bauhaus (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2019); Sonja Duempelmann, Flights of Imagination: Aviation, Landscape, Design (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014); Robin Schuldenfrei, Atomic Dwelling: Anxiety, Domesticity, and Postwar Architecture (Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, 2012). Many articles appeared on camouflage in both art magazines and in the magazine Civilian Defense during the 1940s. ↵

- Apparently Wyeth found a dead crow lying frozen on the ground and carried it back to his studio, where he made two drawings with ink and watercolor. He then returned to the field and made a drybrush drawing of the winter landscape from life. The two sets of drawings resulted in the painting Winter Fields. See David McCord, Andrew Wyeth (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1970), 53. ↵

- Junker, “Marking Time,” 17. ↵

- Podmaniczky, “Andrew Wyeth’s War Memory,” 33, 35. Podmaniczky discusses Wyeth’s fascination with World War I as it developed in his childhood, an obsession owing to the vast repertoire of props and reference materials of that war that his father accumulated and kept in his studio. ↵

- Michaelis quotes Andrew Wyeth’s words on The Big Parade: “This film made such a deep impression on me that it got into my bloodstream.” Michaelis explains that he eventually owned a copy of the film and viewed it “four or five times a year all through his adult life” (N. C. Wyeth, 380). ↵

- George H. Roeder Jr., The Censored War: American Visual Experience during World War Two (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 11. ↵

- Peter Hurd to Andrew Wyeth, December 10, 1944; quoted in Metzger, My Land Is the Southwest, 342. ↵

- Ernie Pyle, “The Final Push,” in Here is Your War: Story of G.I. Joe (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 219. In another instance, Pyle wrote, “I haven’t written anything about the ‘Big Picture,’ because I don’t know anything about it. I only know what we see from our worm’s eye view” (246). ↵

About the Author(s): Cécile Whiting is Professor of Art History at University of California Irvine