Art, Dance, and Social Justice: Franziska Boas, Dorothy Dehner, and David Smith at Bolton Landing, 1944–1949

For several summers in the 1940s, Franziska Boas (1902–1988), Dorothy Dehner (1901–1994), and David Smith (1906–1965) forged a mutually reinforcing artistic and intellectual interchange at Bolton Landing on Lake George in upstate New York—a bucolic location that attracted many visitors, especially in warmer months. With similar political views and shared interests in the visual arts, dance, and music, these artists found commonality and took inspiration from one another’s aesthetic and social concerns.

At the time, visual artists Dehner and Smith lived year-round on a farm near Bolton Landing that they purchased in 1929, shortly after they married. Boas, a dancer and choreographer who regularly and proudly proclaimed her heritage as the daughter of famous anthropologist Franz Boas, had spent time in Bolton Landing as a child. She returned annually from 1944 to 1949 to hold a summer school for dancers.1 Boas and her dancers proved a stimulating addition to the intellectual and cultural life of Bolton Landing. In these years, Boas, Dehner, and Smith independently engaged in formal experiments in their chosen mediums. They also wove radical content into their art practices, professional positions, and community roles. Smith first took up dance as a subject beginning in the mid-1930s and returned to it during Boas’s summers in Bolton Landing. Dance became a subject for Dehner during these years of direct contact with Boas. Because of all three artists’ overlapping interests, their interactions present a useful case study of American modernist practices in dance and the visual arts in the mid- to late 1940s.

The exchanges among these three pioneering American modernists have received little scholarly attention.2 By examining their independent actions and shared connections during this six-year period, I reveal the extent to which they reinforced one another’s commitments to modernist artistic expression and leftist political causes during the final months of World War II and in the years immediately following the conclusion of the war. As I will demonstrate, Boas, Dehner, and Smith, like many artists in the United States, were particularly concerned with anti-fascism and the fight against racial prejudice.3 They were committed to the practice of modernism, shared similar politics, and engaged in social activism, and they believed these concerns could be simultaneously addressed through their respective art forms. Such interests remained at the forefront of their artistic agendas throughout the late 1940s.4 During this period, they sought to address what Dehner called the “state of the world.”5 Each adopted an oppositional stance to engage social justice issues in their art, and they learned from each other how to blend formal innovation with political content. By bringing attention to previously overlooked interconnections among these three artists, I offer a new understanding of each artist’s career in the 1940s, challenging assumptions that American artists abandoned leftist political engagement during and after World War II.

In considering the careers of Boas, Dehner, and Smith from 1944 to 1949, it must be acknowledged that their interactions were complex and multilayered. While Boas was a temporary and intermittent presence at Lake George during the several seasons she summered there, Smith and Dehner were full-time residents. Dehner and Smith had been partners since the mid-1920s. Although their marriage was foundering by the 1940s, their intimate relationship retained a deep bond.6 In contrast, Boas was in an open homosexual relationship with the author Jan Gay. Smith, who was sometimes close-minded, was put off by their lesbianism, which curtailed socializing among the foursome.7 Nonetheless, Dehner and Boas were friendly with one another; they worked together on community projects during the summers and corresponded in the off season, when Boas lived in New York City. Dehner and Smith even visited Boas’s school and interacted with her students. While individual relationships between Boas, Dehner, and Smith were unique, the three shared a mutual interest in advancing modernism and advocating for social justice.

In comparison to the outsized art-historical reputation of Smith, Boas and Dehner deserve greater recognition for their contributions to American modernism. There is still much to learn about Smith’s engagement with dance as an artistic subject and politically driven art of the 1930s and 1940s. By looking beyond conventional scholarly boundaries separating artists and media, I uncover meaningful connections among the three American modernists. Each made work in response to and inspired by the others’ artistic experiments and political commitments. This article contributes to the ongoing process of rethinking mid-twentieth-century American modernism.

Boas’s Dancing School as Site of Modernism

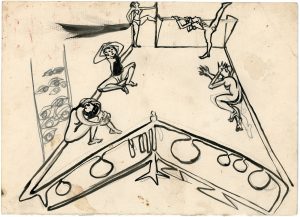

Smith’s 1945 steel sculpture Boaz Dancing School offers a visualization of the overlapping careers of the three artists (fig. 1).8 Made in the second season of Boas’s Bolton Landing program, the work affirms Smith’s interest in the school. More than mere description, Smith’s treatment is a radical experiment in rendering space in three dimensions and a crucial development in his approach to sculptural form. Emily Genauer, an early champion of modern art, described the work as “a witty structure of slanting school-floor, with figures in the different positions of the dance and, at something simulating a window, a confusion of eye shapes representing the curious townsfolk,”9 calling attention to the dancers, their studio, and the local audience.

Bolton Landing residents were curious about the dancers who appeared each summer. Boas had little more than a handful of students in 1944, but by 1945, the school’s roster had grown to eighteen, forming a real presence in the small town.10 The permanent population regarded Boas and her students as “Bohemians,” outsiders both because they were temporary summer residents and because they were engaged in the arts.11 From the beginning, Boas sought to interact with the community; outreach efforts included an invitation to observe Friday evening classes.12 In Boaz Dancing School, Smith captures the locals crowded together and peering at the dancers as a “confusion of eye shapes,” conveying a collective curiosity mixed with uncertainty and even hostility. In doing so, Smith suggests the limited success of Boaz’s well-intentioned gesture of opening her classroom to visitors.

Regardless, Boas as well as Smith and Dehner were genuinely interested in reaching local audiences in Bolton Landing. They made concerted efforts to expose the townspeople to modern art forms, shape them into a receptive audience, and guide them toward a specific social agenda. However, the elitist undertone to their efforts must be acknowledged. The artists wanted to belong to the community but, at the same time, remake the way the local population understood the world. There is a certain irony in the fact that, with Boaz Dancing School, Smith elevated his own art through the vehicle of Boas’s school while rendering the townspeople as incapable of truly comprehending what they saw. Their fascination with the spectacle before them transforms them into nothing more than eyes. The power of their gazes is undercut by their position on the periphery of the composition, where they are literally and figuratively outsiders to the dancers’ world. For them, to see was not to comprehend; in contrast, the viewer of the sculpture operates from a privileged position that simultaneously challenges and rewards careful looking.

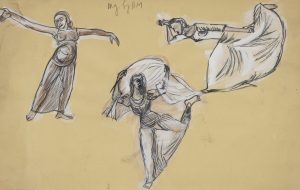

What was there to be seen is informed by two works on paper related to Boaz Dancing School. In each, the room is marked as a dance studio by the presence of a barre mounted on the far wall. Five female dancers warming up for class are distributed around the perimeter. Practice clothes are suggested, but the figures are primarily rendered nude, which allowed Smith to position their limbs precisely.13 The figures’ poses differ slightly from one sketch to the other, but the number of dancers and their basic placement in the room are consistent. One sketch captures the outline of forms (fig. 2), while the other is more concerned with shading significant areas to establish the illusion of three-dimensional forms in space (fig. 3).

There are only three sculpted dancers in Boaz Dancing School, yet each directly relates to a figure in the drawings: the woman seated on the floor with her limbs drawn inward appears in the left foreground of both drawings; the second stretches one leg against a door frame in a pose maintained across all three versions of the composition; and the third, holding an arabesque penché on the far wall in both drawings is repositioned on one of the long sides of the room in the sculpture. The sculptural figures are arranged on a steel plate marked with grooves running lengthwise to indicate the wooden planks of the studio floor. The plate is angled upward and narrows at one end, establishing physical space through a three-dimensional equivalent of one-point perspective. The scale of each figure is manipulated to reinforce a sense of depth, yet this illusionary stratagem is overplayed so that the seated dancer is proportionally much larger than her colleagues. With these choices, Smith employs two-dimensional conventions to establish figures in space as a device to rethink three-dimensional form. He thus simultaneously calls attention to the artistic devices of foreshortening and perspective while thwarting their success.

The crouching figure in Boaz Dancing School is an illuminating example of Smith’s confounding sculptural forms, as it is all but unrecognizable from one point of view to another—something underscored in his photographs of the work (figs. 4 and 5).14 Because the figure cannot be fully comprehended from a single vantage point, the viewer must reorient herself to the sculpture multiple times in order to come to terms with its complexity. In this way, Smith unites spectator and object in a ritualized relationship reminiscent of the formalized movements of dance inherent in the sculpture’s subject. Further, the relationship among the work’s sculptural elements as a concretized spatial procession foreshadows the radical innovations of Smith’s later career.

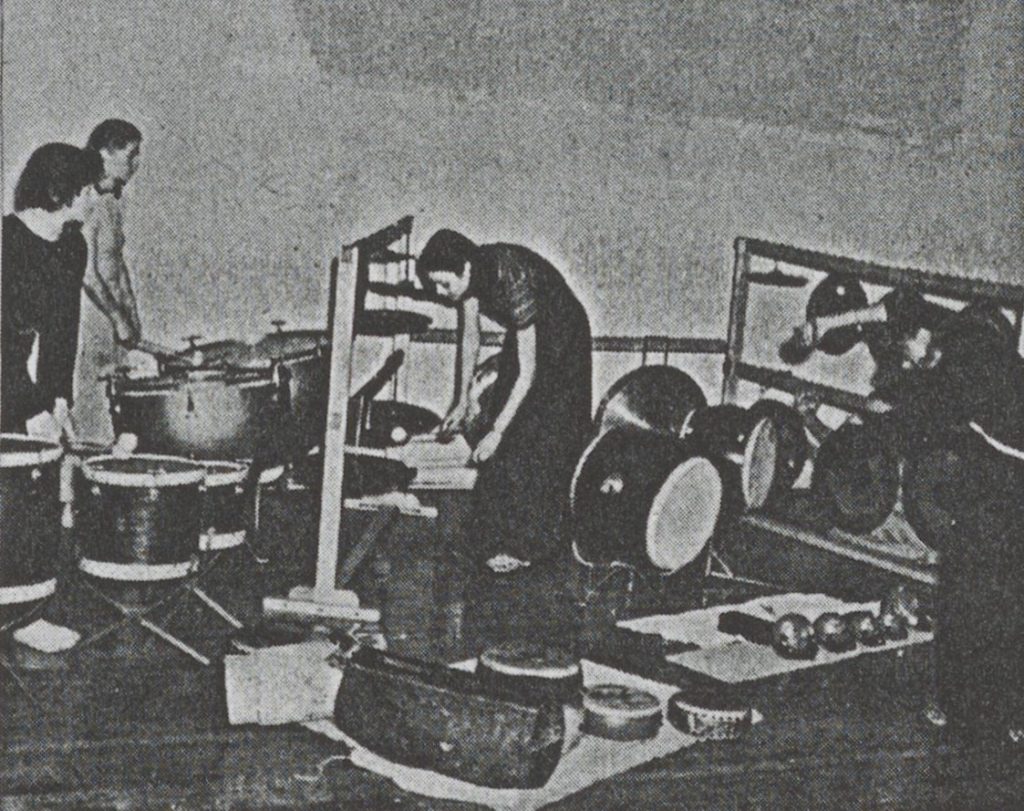

Compared to the treatment of space in the sculpture, the two-dimensional drawings render the dance studio in a more naturalistic manner, with the foreground clearly established by a complex horizontal form. This structure, although absent in the sculpture, can be readily identified as a set of percussion instruments—a commonplace in Boas’s studio and closely tied to her theory and practice. Her extensive collection of drums, cymbals, bells, and triangles appear in a press photograph of her studio (fig. 6).15 Boas was a skilled musician and taught percussion as well as dance. Percussion was a common accompaniment for modern dance in its classical phase. Ease of transport and the need for few musicians made percussive instruments a practical choice for the limited budgets of most modern dance troupes in the second quarter of the twentieth century. But beyond those sensible criteria, the choice also reflects an interest in the primacy of rhythm and a stripped-down musical aesthetic that parallels the focus on fundamental physical movement at the core of the dance performances.

Boas’s use of percussion may have informed Smith’s developing representation of space. Smith’s drawings of Boas’s Bolton Landing studio place the percussion set in the foreground, affirming its physical presence and referencing the dancers’ aural accompaniment. Speaking of percussion music, Boas said, “Sound … create[s] an actual substance to dance in.”16 By conceiving of music as a palpable thing, she emphasizes its physical relationship with dance. In a parallel exercise, Smith embodies the dancer’s movements in space as a route to determining what sculpture could be. The percussion instruments hanging in their frame in the drawings establish a predominantly horizontal element across the foreground that reinforces the illusion of gazing into a fully rendered, three-dimensional space—a room with four sides. Simultaneously, the frame serves as a barrier between the viewer and the dancers’ space. By eliminating the percussion instruments in the sculpture, Smith opens the “fourth wall” of the studio to bring the viewer into the charged space of the dance. The locals peering in from the side have a singular, and thus limited, experience of the room; they are therefore incapable of achieving a full understanding of what takes place there. In contrast, Smith gives the sculpture’s viewer more complete access to a site where space, movement, and sound become one. Smith’s formal innovations of the type found in Boaz Dancing School were acknowledged almost immediately and helped to build the sculptor’s longstanding reputation as a groundbreaking American modernist artist.

Introducing Franziska Boas

In contrast to Smith’s status in the art-historical canon, Boas’s wide-ranging career and contributions to American classical modern dance have only recently begun to receive critical attention. Scholarship in dance history mainly notes her contributions to dance therapy as an emerging field and her work as a percussion accompanist, at the expense of her role as a dance performer, teacher, and choreographer.17 This approach places her at the periphery of the dance world and underscores how scholarship tends to reinforce the significance of figures already deemed central to advancing culture—in this case the “Big Four” of American classical modern dance: Hanya Holm (1893–1992), Martha Graham (1894–1991), Doris Humphrey (1895–1958), and Charles Weidman (1901–1975). Boas was part of a larger circle of influential dancers and choreographers who shaped the American dance world in the 1930s and 1940s. Allana Lindgren’s groundbreaking recent scholarship recognizes the full range of Boas’s contributions, including her social activism and radical pedagogical theory.18 Along with other dance historians, Lindgren’s efforts aim to build a new, more complex, and complete history of classical modern dance in the United States. Figures like Jane Dudley (1912–2001), Katherine Dunham (1909–2006), Sophie Maslow (1911–2006), and Anna Sokolow (1910–2000)19 impacted dance in the 1930s, while Boas was at the height of her influence in the mid- to late 1940s, the same period she was at Bolton Landing with Smith and Dehner.

Boas’s background, training, and experience intersect significantly with that of Dehner and Smith, laying the groundwork for their positive exchanges. The daughter of Franz Boas, she was exposed to a wide range of cultural practices including dance and music. She studied dance formally with Bird Larson, a pioneer in dance education, as an undergraduate at Barnard College, graduating in 1923.20 She took drawing and sculpture classes at the Art Students League (1923–24) and in 1927 traveled to Breslau, Germany, where she studied drawing, printmaking, and sculpture. In New York City, beginning in 1931, Boas continued to study dance and took up percussion with Holm.21 Although Boas built a career in dance, her holistic approach to the arts developed from a foundation that combined visual art, dance, and music.

Holm operated the Wigman School of Dance in New York, dedicated to promulgating the dance theories of German innovator Mary Wigman (1886–1973). Boas’s connection with Holm and thus to Wigman is an important reminder that her lineage was to European sources of classical modern dance. Eventually, those European roots blended with a form of modern dance that emerged from the Denishawn school in Los Angeles, resulting in what became classical modern dance in the United States. The Denishawn school was established in 1915 by dancers Ruth St. Denis (1879–1968) and Ted Shawn (1891–1972) and produced a remarkable group of prominent alumni, including the other three of the Big Four—Graham, Humphrey, and Weidman—who are often credited with creating uniquely American forms of movement.22 Boas was influenced by all four, although Holm was especially important for aiding Boas’s transition from student to teacher.

In 1933, Boas opened her own dance school in New York City.23 There, she continued to evolve Holm’s improvisational modern dance theories and emerged as an influential advocate for percussion accompaniment for dance. In this, she followed Holm, who believed percussion aided students in defining rhythms.24 Although Boas was mostly self-taught as a percussionist, her aptitude in this field came to overshadow her contributions as a dancer. She joined the faculty of the famous Bennington College Summer School of Dance as a percussionist in 1937, 1938, and 1939.25 With the Big Four as founding choreographers, the Bennington program consisted of a rigorous schedule of classes, workshops, and lecture demonstrations, capped by several days of formal performances; it was a veritable wellspring of American classical modern dance. Boas’s immersion in this rich environment yielded many connections. While her position as instructor of percussion eclipsed other accomplishments, Bennington colleagues and students sought out her New York City dance classes.26

Boas formed the Boas Dance Group in 1945, resulting in a limited run of public performances in 1946 before closing two years later.27 The troupe’s commitment to group decision-making and a nonhierarchical structure were completely in line with Boas’s philosophy and socialist thinking of the time, but it also contributed to the company’s disintegration. The absence of a stable and ongoing institution to foster public awareness of Boas’s theories and methods limited her stature in the field. In this, she was her own worst enemy, a matter compounded, Lindgren argues, by her strong repudiation of a “teacher’s name being branded and marketed to promote pedagogical activities.”28 Yet her radical approach to teaching and atypical thinking were congruent with her understanding of modern artistic expression, left-leaning politics, and commitment to social activism. These activities coalesced in the summer school that Boas operated between 1944 and 1949 at Bolton Landing, where she met Dehner and Smith.

Dehner and Smith and the Dance World

While Boas’s summer sessions in Bolton Landing brought modern dance to Dehner and Smith’s doorstep, the couple were already familiar with the evolution of early twentieth-century classical modern dance. From childhood, Dehner was involved with dance as a student and appreciative audience member, encountering the foundational figures of classical modern dance. Her extensive involvement with dance has been acknowledged by other scholars; however, it is worth reviewing with an eye to interrogating her biographical mythmaking.29 As with many of her generation, her initial exposure came through classical ballet. She recalled taking ballet lessons at an early age in the “French tradition” from “Miss Root” in Cleveland, Ohio,30 and seeing Anna Pavlova perform around 1911 with her mother.31 After her parents’ premature deaths, Dehner lived with her aunt Florence Uphof in Pasadena, California, where she continued her studies, adding modern classes to ballet in the late 1910s.32

According to Dehner, this training was encouraged by a neighbor, a male professional dancer at the famous Denishawn School.33 Although this connection was short lived and perhaps only tangential, Dehner may have, in retrospect, recognized how a connection to an influential institution would solidify her bona fides in the dance world and magnify her experiences with modern dance in Los Angeles.34 Dehner was an active dance student there from around 1920 until 1922, when she studied with Violet Romer, a local performer turned teacher. Under Romer’s direction, Dehner publicly performed on at least two occasions what a Pasadena paper referred to as “fancy and classical dances.”35 Romer’s students danced barefoot and en pointe, and their attire evoked the classically influenced costumes of Isadora Duncan (1877–1927), an early advocate of natural movement. A short-lived dream of a career in theater prompted Dehner’s move to New York City, but it was abandoned in 1925 when she set off alone on a lengthy European sojourn. In Florence, Italy, she attended a performance by Wigman, who was also fundamental to Boas’s theories and practice.36 Thus, as a young woman, Dehner lived at the edges of the modern dance world, and Smith was not far off the mark, saying, “When I first met Dorothy Dehner she had been a successful dancer.”37

The two met in 1926, when Smith coincidentally took a room at the same Upper West Side boarding house where Dehner had been living since 1925.38 More than four years his senior and arguably more worldly, Dehner was eager to share her enthusiasm for and knowledge of cultural matters, including dance.39 Their joint exposure to the art form was ultimately eclectic. One of their first cultural outings after their marriage was to a performance by Martha Graham on February 12, 1928.40 They also attended performances of the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo (which first toured the United States in 1933) and the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in 1936 while visiting London.41Throughout this time, Dehner continued to practice dance.42 She modeled dance poses for Smith and occasionally performed for Smith alone and at small social gatherings.43 It is also possible that she continued to take dance classes; she later claimed to have studied with Graham in the 1930s.44

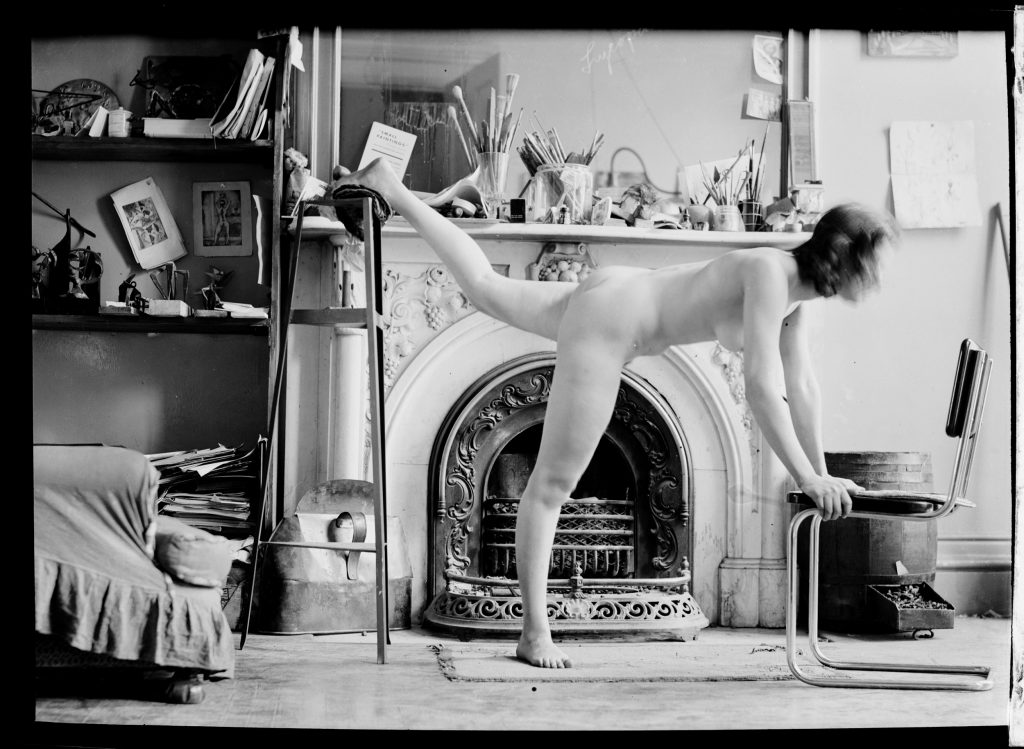

When Smith first embraced dance as a subject for his art beginning in the mid-1930s,45 he took photographs of Dehner in dance poses and employed them as the basis for artworks (fig. 7). He frequently worked from photographs in this period. In addition, he clipped images from popular publications to use as inspiration. He was interested in all types of rhythmic physical expression—social, folk, ballet, and modern.46 His choices reflect his dance experiences with Dehner and his interest in the major figures of the emerging field of American modern dance.47 For example, in a single notebook of 1938, Smith made sketches after photographs of Graham, Holm, and Weidman.48

By far the best known of Smith’s two-dimensional treatments of dance are three independent drawings (fig. 8, 9, and 10) based on photographer Barbara Morgan’s famous 1941 book Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographs.49 Each sheet includes multiple vignettes of dancers; the individual groupings follow the book’s order, reinforcing the connection between the sketches and Smith’s experience of looking at the published photographs. In her introduction, Morgan acknowledges the challenge of translating “the intense reality of movement contained in the original dance” into still photography.50 With his sketches after her photographs, Smith explores Graham’s choreography as mediated by Morgan’s choices. One cannot help but think he was simultaneously working through problems he deemed relevant to his own concerns in capturing movement, a matter he would take up again in Boaz Dancing School.

Leftist Ideologies and Political Organizations

Smith’s specific interest in Graham’s conception of the body moving in space as recorded by Morgan’s photographs highlights the modernist orientation of these artists. Their respective formal experiments broke traditional boundaries and embraced new modes of expression, but their parallel commitment to modernism was not limited to stylistic issues: they also shared an interest in a leftist avant-garde political agenda. The dynamic intersection of experimental art and radical politics gave rise to a politicized community of creatives in the 1930s to which Smith, Boas, Dehner, Graham, and Morgan all belonged. At Bolton Landing in the mid- to late 1940s, Boas, Dehner, and Smith continued to share a worldview shaped by leftist policies rooted in the previous decade, including their stand against fascism and activism against racial prejudice.

In the 1930s—an era well known for group action—professional associations proved especially effective in promoting solidarity among individuals with similar interests. Such organizations provided a useful collective identity, advocated for the rights of members, and promoted causes they considered relevant. As many of these groups were communist influenced, their policies frequently aligned with the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA). In 1935, Smith and Morgan both signed the “Call for the American Artists’ Congress,” a document frequently used as a measure of leftist commitment on the part of visual artists of the era.51 The American Artists’ Congress (AAC) was a communist-influenced organization intended to foster community among artists and provide a platform to stand against war and fascism.52 That both artists signed the call signaled their individual commitments to the organization’s goals, although it does not mean the two actually met. Each participated in AAC exhibitions over the next several years, offering evidence of their support for the organization’s professional and political objectives.53

The AAC’s membership rolls drew almost exclusively from visual artists, but its programming acknowledged shared concerns across the arts. Graham addressed the topic “The Dance, an Allied Art” at the second annual AAC meeting in December 1937.54 Concurrent developments in dance reflected the belief that such organizations reinforced solidarity among cultural workers and served as a springboard for social activism. In 1936, the National Dance Congress was established with the involvement of a virtual who’s who of classical American modern dance, including Boas, Graham, Holm, Humphrey, and Weidman.55 Later that year, all five participated in the single meeting of this short-lived organization.56 On the final day, the Congress adopted resolutions that paralleled specific concerns addressed in the call for the AAC, notably opposition to war, fascism, and racial discrimination. Not surprisingly, such issues were also at the forefront of the popular front agenda of the CPUSA.57

To be anti-fascist in the late 1930s was to be anti-war. One need only think of the AAC, whose members rallied around the motto “Against war and fascism.”58 Though the pairing may seem counterintuitive, for those following the policies of the communist party in the popular front era, to be against war was to refuse elites the opportunity to manipulate workers into armed conflict to their own physical, political, and economic detriment. And to be against fascism was to reject a repressive political system that threatened any opportunity for the working class to protect its own interests. In the mid-1930s, people on the Left saw fascism as imperiling all the nations of the developed world, not merely those where authoritarian regimes already held power.

Dehner and Smith were committed leftists in the early 1930s, and their lengthy trip to Europe from 1935 to 1936 confirmed for them the looming threat of fascism.59 After returning to the United States, they eagerly joined political and professional colleagues in supporting anti-fascist and anti-war causes. Smith joined the Artists’ Union—another communist-influenced professional organization like the ACA, which strove to protect artists while supporting a broader agenda of workers’ rights.60 Dehner was not an official member of either but participated in meetings, rallies, and marches.61 Group action was one way to demonstrate commitment, but evidence of their political agenda also appeared in their art.

Dehner’s art from this period occasionally turns a sympathetic eye to society’s underprivileged, and Smith’s lays out his anti-war, anti-fascist agenda in explicit detail through his Medals for Dishonor—a series of fifteen metal plaques first exhibited in 1940.62 With dense imagery and complex symbolism, the medals mounted a pointed attack on powerful institutions that Smith viewed as abusive of the poor and weak. Among those “honored” were the press in Propaganda for War and men of the cloth in Cooperation of the Clergy. The anti-war, anti-fascist worldview underlying his project was also on prominent display in Munition Makers and Private Law and Order Leagues (fig. 11). A selection of the Medals for Dishonor series appeared in the AAC’s anti-war exhibition of 1941, cementing the link between the artist’s personal agenda and group affiliation.63

Although the Left did not abandon the fight against war, the anti-fascist cause gained new intensity with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936. When radical conservatives took up arms to challenge the democratically elected Spanish government, the resulting conflict was wrenching confirmation of the threat posed by fascism to those on the Left. According to Dehner, Smith briefly considered joining the Abraham Lincoln Brigade of American volunteers fighting alongside republican forces in Spain, but ultimately he settled for using his art to bring attention to the cause and raise funds for the suffering Spanish people.64

Sympathetic dancers also used art in service of the cause, choreographing works that specifically addressed the Spanish Civil War and staging performances to benefit medical aid for republican soldiers. Between 1937 and 1939, at least twenty such dances premiered, including Graham’s solo Deep Song (1937), described in program notes as presenting “the torture of mind and body experienced in common by all people who react to such suffering as the Spanish People have faced.”65 Dances inspired by the Spanish conflict were performed in a variety of contexts, including programs with no ostensible political agenda and as part of more casual statements of support for the Spanish cause. On two notable occasions—May 23, 1937, and February 5, 1939—the luminaries of the modern dance community rallied in support of Spanish loyalists. These dance concerts were organized under the auspices of the American Dance Association—founded in 1937 and devoted, like so many similar groups, to advocating for their artists’ professional standing as well as “promoting world peace and fighting fascism.”66 The dance community’s engagement with the struggle against fascism and specific efforts to support Spanish democracy thus parallel the concerns and actions of other creatives in the 1930s.

Shared Interest in Racial Inequality

In these same years, racial inequality regularly garnered attention from left-leaning individuals and organizations. At a time when racism was deeply entrenched in the national psyche and segregation was the law of the land in the United States, the CPUSA encouraged anti-racist activism throughout the 1930s.67 The 1935 “Call for the American Artists’ Congress” identified discrimination “against Negroes” as one justification for “an artists’ organization on a nation-wide scale, which will deal with our cultural problems.”68 The Dance Congress of May 1936 similarly acknowledged segregation and suppression of the “Negro People in America” in its concluding resolutions.69

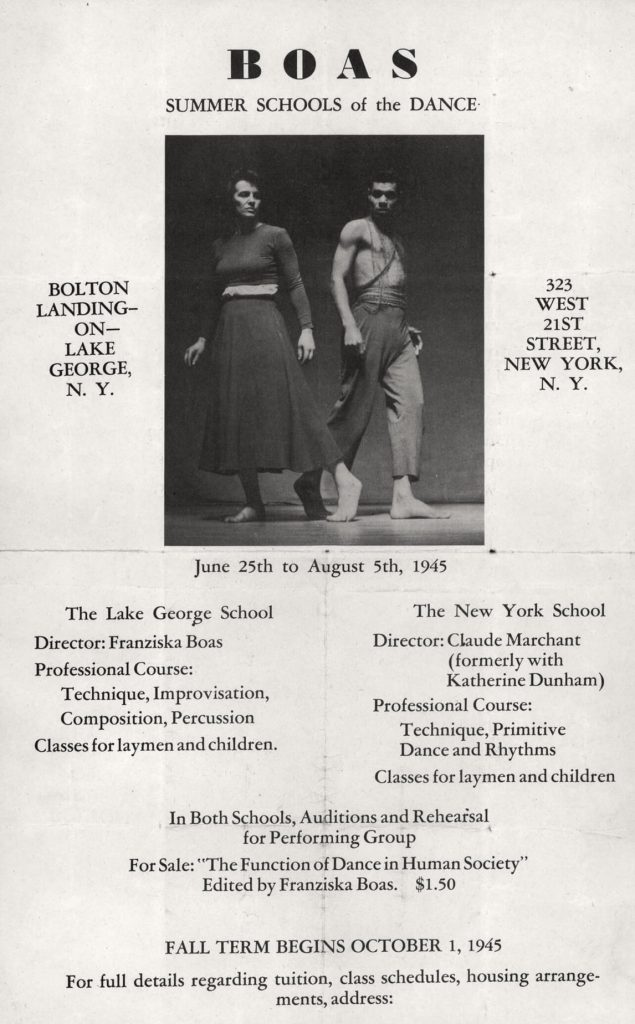

In keeping with their leftist agendas, Boas, Dehner, and Smith were all involved in fighting racial discrimination long before meeting in Bolton Landing. Boas’s understanding of racial prejudice was rooted in her father’s groundbreaking anthropological studies, which served to undermine pseudoscientific links between race and intelligence.70 Her theoretical commitment to the concept of racial equality was supported by active efforts to recruit African American students to her New York City dance school. Starting with its 1933 founding, she conscientiously worked toward integration, running advertisements in African American newspapers such as The Pittsburgh Courier.71 Her faculty and staff also reflected Boas’s goals for integrating the dance community.72 Claude Marchant (1919–2004), an African American dance pioneer, studied with Boas and later taught at her school.73 He had performed with the influential African American dancer Katherine Dunham in the mid-1940s.74 Dunham’s choreography was informed by anthropology, resulting in a unique and influential blend of classical modern dance, African ritual, and Caribbean rhythm.75 Unlike Boas, Dunham secured her reputation and legacy by founding a successful touring company and school. Dunham’s school began in 1944 briefly as a joint venture with Boas. The two united in support of racial equality, and the school reflected their shared goal of using “dance education as a means of anti-racist activism.”76 It reflected Boas’s longstanding commitment to the racial integration of faculty, staff, and students in New York City. Boas established her summer school in Bolton Landing that same year.

In upstate New York, Boas found allies in Dehner and Smith, who had taken up parallel concerns in the 1930s. In 1935, Dehner advocated for Angelo Herndon, a young African American communist organizer in Atlanta, whose arrest and conviction as an insurrectionist made him a CPUSA hero. Dehner collected Bolton Landing signatures to petition the Georgia governor to free Herndon and repeal the “insurrection” law, and she sought donations for his legal-defense fund handled by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a communist-led organization.77 Smith addressed related subject matter in his Private Law and Order Leagues (1939) from the Medals for Dishonor series (fig. 11). Among the many symbols Smith used to address the subject of American vigilante groups, a series of what first appear to be mountains running along the top of the medal are really shrouded heads of Ku Klux Klansmen surveilling the landscape below with a lynch tree heavy with “strange fruit” (fig. 12). Lynching was a form of domestic terrorism that functioned as a social device to terrify and suppress the African American population. The American Left was vociferous in its attacks on lynching and the white-dominated legal system that tolerated it. Smith was among many visual artists who brought attention to the terror and injustice of lynching in the 1930s and 1940s, along with choreographers who created dances with similar themes, such as Weidman’s Lynchtown (1936).78

As a lived example of Boas’s commitment to racial integration, her summer school challenged the Bolton Landing community to accept racial diversity. Because students resided communally to facilitate the intensive program, the residential component provided Boas the opportunity to “demonstrate how people of different races could learn together and live together harmoniously.”79 If modern dance was a challenge for the small town, racial integration was a greater one. From the beginning, Boas worked to build bridges between locals and dancers and to demystify the activities in her studio. As depicted in Smith’s Boaz Dancing School, Friday evening sessions were open to visitors, and Bolton Landing residents could join the students’ exercise classes free of charge.80 Boas’s commitment to racial integration was also publicly manifest in the 1945 summer session poster featuring a photograph of Boas performing with Marchant (fig. 13).81 However, African Americans associated with the program experienced discrimination in Bolton Landing.82 Still Boas persisted in bringing a racially diverse group into town, summer after summer. Her partner, Gay, recorded that the community seemed to learn to accommodate their presence as years passed.83

Boas carefully fostered the participation of African Americans in her Bolton Landing program. She directly contacted historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), alerting them to an available scholarship for Black students.84 Students from Hampton Institute and Fisk University held scholarships in 1946, 1947, and 1948.85 Boas publicized the school’s success in recruiting African American students through an August 21, 1946, press release consisting of a photograph of Boas with two African American students from the 1946 summer session accompanied by a brief text.86 The release was distributed by the Associated Negro Press, a national news agency providing stories of interest to African American subscriber newspapers.87 The photograph and text was printed in at least ten different papers across the country between August 23 and September 22, 1946.88

Constructed to celebrate racial integration at the school, the press release foregrounded the accomplishments of HBCU students. The headline, “Fisk and Hampton Students Attend Boas Summer School,” established a connection between Boas and HBCUs that no doubt caught the attention of newspaper editors and readers. The text delineated the accomplishments of Isabel Hamil from Fisk and Curtiss James from Hampton before introducing Boas as “the daughter of the famous anthropologist” who “carries out in her school of dance the same principles of racial equality that marked her father’s work.” Racial integration was further underscored by the accompanying photograph of the two youthful African American students on either side of the white, middle-aged Boas (fig. 14). The photograph stands as a document of the strengths and limitations of Boas’s efforts to achieve racial equality since, despite her good intentions, Boas appears as a figure of (white) authority due to her central position, greater age, and race. She was, nevertheless, committed to fighting racial injustice and believed it was necessary for all people to acknowledge the realities of racial discrimination, protest the status quo, and take action.89

Expanding Boundaries and Building Community in Upstate New York

Whatever the limitations of Boas’s approach, she had bold ambitions for her intensive residential summer school in Bolton Landing. To provide a transformative experience for students and expose them to professional practices, Boas built an unusual curriculum. Along the way, she engaged members of the local community and raised the profile of the arts for Bolton Landing. Because Boas conceived of creativity as fostered across many fields, as hers had been, she constructed an experience that followed her own training and practice. The raison d’être for the school may have been dance, but Boas formalized participants’ exposure to music, visual arts, and creative writing in ways distinctive from her New York City school. Full-time summer school students studied dance morning and evening, with music, art, and writing on alternating afternoons. The aggregate experience offered a comprehensive arts training.

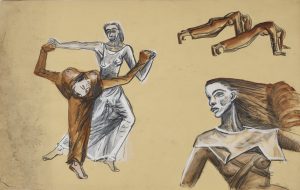

Although Boas was responsible for teaching most of the dance and some of the music classes, additional faculty members filled out the curriculum. Each summer, Gay taught creative writing.90 Boas called upon Dehner and Smith to teach visual arts. Smith’s involvement was limited to a few sessions in 1945, but in these brief encounters, he critiqued the students’ clay “figures of dancers.”91 The figures likely had roots in an exercise Boas employed in the dance studio, where students used clay to shape their bodies in movement—a concrete example of her commitment to using one art form to inform another.92 Later she would ask the students to repeat the exercise to reveal greater physical self-awareness. For Smith, seeing students conceptualize their dancing bodies in three-dimensions likely affected his own thinking about issues he explored in Boaz Dancing School, which he made the same year. Boas invited Smith to teach a full sculpture course for the summer of 1946, but he declined.93 Instead, Dehner taught painting in 1946 and again in 1947.94 She described her class as “fun to do,” reporting that students “made up a dance for me . . . an artist dance with models falling from fatigue, etc. Quite funny and good.”95 The choreography was a charming tribute to Dehner but also referenced the fact that Boas’s students served as models for both Dehner and Smith.

Students posed for the visual artists summer after summer, providing a convenient supply of lithe, strong bodies to sketch in the studio. The dancers’ physical training—complemented by their self-awareness built by Boas’s classroom exercises—made them especially successful artist’s models; as Dehner observed, “God how they do love to POSE.”96 Working with live models was not unique to this period in Dehner’s and Smith’s careers. They employed models from their student days onward, believing that sketching from life helped avoid being “stymied.”97 However, access to models was sometimes limited by circumstance, including financial restraints and their relative isolation on the farm. Therefore, Dehner and Smith welcomed the arrival of dance students each summer.

Their engagement with the dancers—as models, students, and performers—heightened the significance of dance as subject matter for their art. Through their firsthand involvement with Boas’s curriculum and its conscious embrace of multiple art forms, Dehner and Smith were part of a carefully planned system that closely mimicked their own contemporary practices in which dance, music, and poetry were complementary, overlapping sources for visual art. Further, Boas and her students had a significant impact on the local community, since, as Dehner commented, they “put culture in the town.”98 For Dehner and Smith, full-time residents of Bolton Landing who remained alien to most of the locals, there had to be comfort in reinforcements arriving every summer to mold a creative community, further legitimize modern artistic practices, and foreground a transformative social agenda.

Music, Concerts, Festivals

Boas began her summer school with an ambitious agenda and aimed to elevate it year after year. Music was an especially important element, given its complex relationship with dance. She took advantage of summer visitors and locals to augment her percussion courses and round out the music component of the curriculum. She also sought compositions to inspire original choreography and showcase her and her dancers at the end of each season. In 1946, Hugh Wilson, a local Yale musicologist, led the music program.99 Boas thought in grander terms the next summer, hiring Canadian composer Colin McPhee (1900–1964) as composer-in-residence.100 In 1948 and 1949, Meyer Kupferman (1926–2003), a rising star in the music world in the late 1940s, filled the role of resident composer.101 Their collaborations were typical of Boas’s professional relationships. She targeted people on the rise who were eager for opportunities and exposure and undeterred by a meager salary.

The escalating involvement of composers-in-residence paralleled the increasingly elaborate public performances at the end of each season. From the first year onward, dancers performed as part of a community concert with the Bolton orchestra.102 By 1948, this event had evolved into the full-fledged, three-day Bolton Landing Festival of Music, with one night devoted to a performance by Boas and her students.103 Both Dehner and Boas worked with locals to organize a more extensive festival for 1949; although the event fell apart at the last moment, plans were so advanced that the program survives in typescript.104

Dehner made a concerted effort to include the visual arts in the evolving festival. She took responsibility for hanging an art show for the 1948 festival, as an extension of her annual effort to present small exhibitions of local artists in the Bolton Landing Barn Playhouse, where summer stock theater was held.105 The 1949 program set out an even more ambitious goal as Dehner called for “an exhibition of modern American painting that will include the best work being done in the contemporary field.” She underscored the significance she assigned to contemporary American art, continuing: “Excepting a handful of modern French masters, we believe the most creative and most imaginative work in present day painting and sculpture is being done in the United States.”106 Even though the ambitious exhibition never materialized, Dehner’s perceptions were prescient. This was the same summer when Life magazine signaled a new level of interest in modern American art by famously asking, “Is [Jackson Pollock] the greatest living painter in the United States?”107

Propagating modern American art was the primary reason Dehner dedicated so much time and energy to the festivals. Along with curating exhibitions, she served as art director for the 1948 and 1949 festivals, which she described as “endless work and drawings for publicity etc.”108 Boas was dance director for these same festivals. The draft of the 1949 program reveals another previously unacknowledged professional collaboration between them: Dehner was credited with creating the sets and costumes for The Cycle, a dance choreographed by Boas to music by Kupferman.109 This project never reached the stage, given the abrupt cancellation of the festival that year, but the short time between cancellation and the scheduled performance makes it likely that Dehner’s designs were underway, even if they were never used. The project affirms the level of familiarity and interest Boas and Dehner had in each other’s artistic output.

At that same canceled performance, Boas was scheduled to be joined onstage by Lin Pei-Fen, identified in the program as “a native of China, from the province of Canton.” Early in 1949, Lin performed across the United States, as reported in the major dance publications of the day, in which her approach was characterized as a blend of “Oriental dance” and “Graham technique.”110 Lin’s invitation to perform at Bolton Landing was another example of Boas’s concrete efforts to bring racial diversity to American dance and to the town. Lin’s tour was sponsored by the East and West Association, an organization founded in 1942 by Pearl S. Buck (1892–1973) to foster cultural exchange and better understanding between Asia and the West.111 Buck, the daughter of American missionaries, had lived much of her life in China and gained fame as an author and popular authority on the country when her novel The Good Earth, a sympathetic account of rural life in a Chinese village, won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1932.112 Smith and Dehner were already familiar with Buck and her writings through their research on China and its politics when Smith was commissioned to design a medal for the Chinese government in 1941; they found her liberal views and sympathy for the Chinese people appealing.113 Lin’s invitation to join the festival thus provides a further instance when Dehner’s and Smith’s connections and concerns overlapped with those of Boas.

Reverberations of the Spanish Civil War in the Postwar World

In 1946, Boas choreographed a solo concert piece she titled Goya-esque. It debuted that year as part of the Boas Dance Group’s performances in New York City and was performed again at the 1948 Bolton Landing Festival of Music. The title of the work immediately invokes Spain and Spanish culture through its reference to the great romantic artist Francisco Goya (1746–1828), and Boas made a tighter, specifically anti-war connection to Goya’s art by inserting the phrase “after ‘The Horrors of War’ etchings by Francisco Goya” below the title in the printed program.114 Goya’s Los desastres de la guerra (1810–20) was a well-known series of approximately eighty prints inspired by the dramatic social upheaval and unbridled violence unleashed during the Peninsular War in the early nineteenth century. Horrors of War served as a powerful source of inspiration for 1930s artists responding to the contemporary crisis in Spain and the wider threat of fascism. In fact, Smith cited Goya’s series as a direct influence on his Medals for Dishonor.115

For late 1940s audiences, Boas’s title and the dance’s anti-war theme would reverberate with associations to the Spanish Civil War. In taking up this topic, Boas projected her ongoing leftist political view of world events. Although the dance was generated in New York City, it was produced after her first two summer sessions at Bolton Landing. Her contact with Dehner and Smith may well have reinforced Boas’s unease over the political agenda of world leaders at the conclusion of World War II. For those still sympathetic to the Left, such concerns were justified by the tenuous outcome of the war. As the conflict in Europe ended, the impending Allied victory over the Axis powers was undermined by an Allied tolerance of fascist tendencies, including the February 1945 decision of Britain and France to affirm Francisco Franco as Spain’s head of state. These fears were compounded by evidence of the European nations’ ongoing totalitarian and imperialist policies in the years immediately following the war. Leftist publications including the Daily Worker, leftist-influenced newspapers such as PM, and even mainstream press outlets such as the New York Times and the San Francisco Chronicle reported regularly on these issues in the late 1940s.116

The circumstances surrounding the making and presentation of Goya-esque help clarify the meaning of the dance in the context of Boas’s career. It was choreographed in April, while Boas was developing an untitled concert piece for a series of New York City performances by the short-lived Boas Dance Group.117 Boas worked with the dancers to compose a piece “inspired by the persecution of republican groups during the Spanish Civil War.”118 As already mentioned, Boas was little concerned with conventional choreography—a key reason her profile in the history of American classical modern dance is so limited. Instead of imposing ideas on fellow dancers in a formalized, repeatable sequence of movement, she taught personal expression to dancers who then applied generalized techniques to their practice.119 As the work progressed, the content shifted through this expressive process from the Spanish Civil War to encompass a more immediate topic for the interracial dance troupe: race relations in the United States.120 Certainly, the evolution of the troupe’s dance provides a fascinating example of elision between subjects of foremost concern to the cultural Left as injustice of one sort (fascism) merged with another (racial discrimination).

Although the work of the group dance evolved beyond the nominal topic of the Spanish Civil War, Boas took up the subject for her solo Goya-esque. The anti-war theme of Goya’s prints was a powerful force in shaping the content of her piece, and it set the horror of war rather than the hope of peace before her postwar audience. Goya’s series was a furious indictment of senseless violence, exposing the suffering of the weak subjected to unbridled power. The savagery of his imagery was at once in keeping with a romantic sensibility yet timeless in its outrage. The passion imbued in his project carried over into Boas’s treatment of a parallel subject; as a dancer, Boas found inspiration in Goya’s two-dimensional prints, which provided a meaningful formal exchange between the visual arts and dance. As Lindgren observes, Goya-esque attempted “to reconcile the pictorial power and stasis of visual art with the three-dimensional mobility of dance.”121

In Goya-esque, Boas’s choreography responded to the settled forms in Goya’s prints and the reality of her body in motion as a bridge between two-dimensional and three-dimensional art forms. Classical modern choreography self-consciously exploited the contrast between stillness and motion fundamental to all forms of dance. For Boas, this tension was likely heightened by thinking about the fixed images of Goya’s prints in relationship to her actions on the stage. However, Boas was also thinking specifically in terms of the exchange between the two-dimensional images in relationship to her three-dimensional body. Goya’s aggressive renderings of degraded, tortured forms—sometimes no more than dismembered fragments—were a radical rejection of the classical celebration of the human body in either the visual arts or dance. For a dancer who thought about the human body as a complete, singular instrument, the relationship to Goya’s brutalized figures must have been both fascinating and horrifying. The challenge of conceptualizing and then accommodating the differences she set for herself with the parameters of this project bear striking similarities to the complex depictions of three-dimensional forms referencing two-dimensional schemas found in Smith’s Boaz Dancing School. In this way, parallel explorations of form as well as content emerged in the work of Boas and Smith in the mid- to late 1940s.

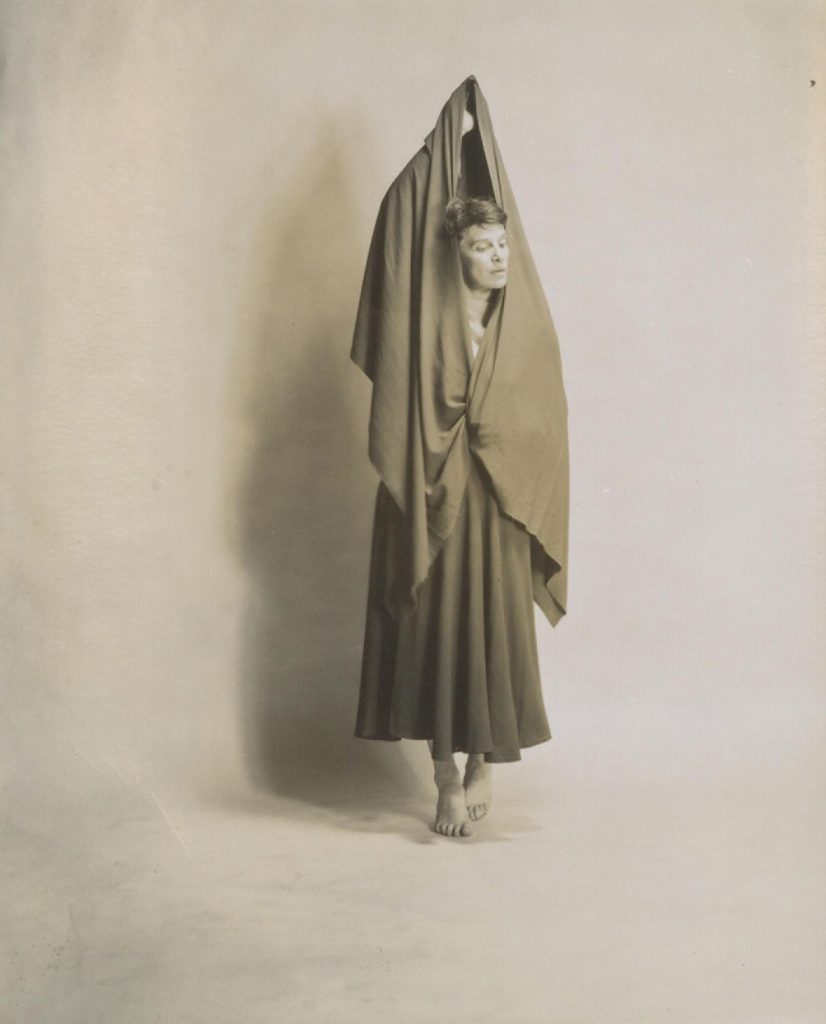

Goya-esque stands as an intriguing marker of Boas’s career, yet there are distinct challenges in establishing what an audience would have experienced. As is true for almost all of Boas’s dance compositions, little documentation survives. Without a company to preserve and pass on her choreography from one generation to the next, there is no living memory of her dances and only a patchy historical record.122 Still, more traces exist for Goya-esque than for most of Boas’s oeuvre: Kupferman’s original score is preserved; the dance was partially described in contemporary reviews; and, most significantly, more than twenty photographs survive that capture snapshots of Boas’s performance.123

These photographs provide a crucial, yet limited, record of Goya-esque. Because they are still images, they capture only fragments of the dance, perhaps unintentionally intensifying the parallels to Goya’s radical dismemberment of the human body. In addition, there is no indication of the order in which the photographs were taken and therefore no clear information as to their relationship to the sequence of movements that made up the dance. Nonetheless, the photos offer a tantalizing and important glimpse into Boas’s performance, displaying both her artistic innovation and the strong classical modern dance roots of her practice.

Among these connections to classical modern dance are Boas’s bare feet, movements featuring dramatic contractions and extensions of the body, and the use of a simple yet versatile costume. Performing barefoot allows modern dancers to move beyond the physical confines of classical ballet shoes and gain an alternate sense of balance thanks to a stronger, more direct relationship with the ground. The orientation of movement around contraction and release (to use Graham’s famous terminology) gives classical modern dance a more organic quality than ballet’s continual battle against gravity (fig. 15).124 And, as sets and elaborate costumes were expensive to commission, maintain, and transport, a spare background and straightforward attire can contribute to the content of the piece.125

As demonstrated in the surviving photographs, Boas’s costume for Goya-esque comprised three simple elements: a loose, long-sleeved, round-necked top; a full, ankle-length skirt; and a large rectangular scarf. Even in the sepia-toned photographs, it is evident that the blouse was of light-colored cloth contrasting with the darker tone(s) of the skirt and scarf. Using her body and the costume—especially the scarf—Boas was able to achieve a wide range of dramatic shapes, capture an array of moods, and perhaps communicate multiple characters without necessarily shaping a conventional narrative. Some photographs capture the scarf tightly draped over her head, shrouding her identity (fig. 16). In others the scarf is wound around her neck, exposing her garments and face, thereby revealing her as a specific individual—the dancer Boas but also perhaps a female protagonist in the drama (fig. 15). She also employed the scarf to isolate elements of her body and transform its shape, as when she held the scarf aloft with one hand while holding it closed on her torso with the other, thus highlighting her face and transforming the contour of her body (fig. 17).

This last effect, where the fall of the fabric achieved a sculptural form reliant on but largely independent of the body, may have been influenced by Goya’s fragmented bodies, but it also immediately calls to mind Graham’s exploration of grief in her dance Lamentation (1930), recorded in Morgan’s well-known photographs (fig. 18). Graham’s famous manipulation of the fabric tube that encased her body in her “dance of sorrows” would have been familiar to Boas, since she had been at Bennington College when Graham performed it.126 However, it is important to note that such similarities suggest not so much the derivative nature of Boas’s composition as the fact that it was of its time. As with Lamentation, Goya-esque addressed intense emotion, the expression of which is one of the cornerstones of classical modern dance.

As captured in the photographs of Goya-esque, Boas employs her costume not just to explore the literal formal interaction between costume and body but to communicate diametrically opposed aspects of her theme. A contemporary critic described Goya-esque as projecting “the alternate tensions of hatred and despair in a dark, morbid creature submitted to war, and inevitably being destroyed by it.”127 This phrasing suggests that Boas’s dance captured both the aggressor and the victim in the sole figure of the dancer, who ultimately experienced not a triumphal, transcendent unification but a singular, crushing defeat.

The words of a supportive writer may have captured the essence of Goya-esque, but the link between Boas’s experimental choreography and a powerful social justice agenda remained problematic for some cultural critics of the late 1940s. Their position was an extension of one established in the heyday of the politically active 1930s by critics who took a negative view of forms of expression that, in their opinions, unnecessarily complicated pure art with overt, specific subject matter. This modernist critical perspective was fully on display when the national dance press reacted to the 1946 performances of the Boas Dance Group (which included Goya-esque). While some critics were sympathetic to what had been achieved by Boas’s responses to Goya, the Dance Observer questioned the very legitimacy of Goya-esque as a dance.128 Its critic, writing in a publication generally sympathetic to modern dance, found the piece had too specific a social agenda and not enough “dance sense.”129 This assessment serves as a powerful reminder of the frequent critical resistance experienced by artists of the era who sought to blend experimental form with politicized subject matter; it also reveals the dominance of formalist criticism, which advocated for the purification of the medium to the exclusion of all other considerations.

Similar critiques were lodged against visual artists. At a time when Smith’s radical reworking of sculptural materials and his own rethinking of the relationship between two and three dimensions was attracting favorable comments from critics, his works with a strong social message were less warmly embraced by leading critics.130 In the same months as Boaz Dancing School, Smith made several sculptures with politically charged, leftist-oriented subject matter. Representative of these are False Peace Spectre (1945) and Perfidious Albion (1945–46), both of which signaled his belief that the end of World War II simply led to the continual prospering of the capitalist system under relentless authoritarian and imperialist governments.131 In False Peace Spectre, he fabricated a grotesque caricature of a dove of peace as a menacing bird of prey clutching a human victim in its beak in place of the traditional olive branch (fig. 19). His association of this rapacious, duplicitous power with capitalism is affirmed by a related drawing labeled “Spectre with capital peace.”132 Smith’s Perfidious Albion maintained False Peace Spectre’s ideological association between expansionist political power and a capitalist economy while establishing a specific link with Great Britain through the ancient name Albion (fig. 20). In constructing a female personification of Britain as an imperialist monster, Smith signaled his view of the empire as a negative force on the world stage—its wealth, indicated by the complex and disturbing fecundity of the sculpture’s surface, coming at the expense of other cultures.133

Both these sculptures demonstrate Smith’s commitment to a leftist political agenda at the conclusion of World War II. The symbolism of each work conveys a strong, perhaps heavy-handed message, even if that content is somewhat obscured by a surrealist complexity. At the same time, these sculptures display Smith’s increasingly inventive use of materials and techniques compared to traditional sculpture. False Peace Spectre combines bronze and steel, cast and found objects, into a form abstracted from nature, while Perfidious Albion fuses cast bronze and welded iron. Modernist critics generally chose to brush aside his continued attempts to address politicized subject matter and focused on his novel use of materials, innovative formal achievements, and radical conceptualizations of space in Boaz Dancing School and other sculptures from the same prolific period in Smith’s career. Whatever solace Smith and Boas may have found in one another’s parallel responses to the postwar world, they were subject to similar, reductive pressures from dominant critical voices.

Dehner’s Ongoing Anti-Fascism

In the late 1940s, Dehner, like Boas and Smith, responded to a worldview shaped by her experiences of the 1930s and early 1940s, but for the first time she turned to dance as a vehicle to convey her visual ideas. The exploration of dance in her art aligned with her friendship with Boas and their shared interests in art and politics. The late 1940s was a complicated period for Dehner. She loved aspects of the farm at Bolton Landing and took pleasure in her engagement with her community. She found a new direction for her art by turning to large-scale drawings and away from painting, which had dominated her practice from her student days. In addition, she was ambitious, and her efforts were rewarded by several exhibition opportunities.134 However, her relationship with Smith was increasingly tense. His episodes of verbal and physical abuse plagued their marriage from its earliest days.135 One especially intense episode of domestic violence led Dehner to leave Smith for approximately five months in 1945, although she chose to return later that year.136 In her art, the private pain at her disintegrating marriage was fused with the lingering horror of World War II and her fear that the flames of conflict had not been truly extinguished by the official declaration of peace.

These dual personal and political concerns are evident in many of the drawings Dehner produced in this period of tortured bodies and ravaged landscapes. Previous scholars have read them primarily as Dehner’s response to the circumstances of her personal life. Art historian Joan Marter interprets them as “related to post war tensions” but as having “more to do with her state of mind in these final years of her marriage to David Smith.”137 I argue that Dehner’s ongoing concerns with the threat of fascism, which paralleled the political perspectives in Smith’s and Boas’s contemporaneous artistic output, deserve greater attention, although her personal suffering no doubt affected her works’ emotional resonance. Dehner executed multiple drawings of dancers during these years that fall within this spectrum between individual anguish and universal suffering. Scholars have also mostly narrowed their analyses of these works to the personal, focusing on Dehner’s own training and practice of dance and the influence of Smith’s interest in the subject.138 Until now, there has been no discussion of Boas’s impact on Dehner’s representations of dance.

I believe that acknowledging Boas’s influence on Dehner’s drawings is a necessary component to a rethinking of Dehner’s early career that counters using Smith as the sole gauge to measure her activities. As is so often true of scholarship addressing artists in intimate heterosexual relationships, the male is assumed to be the dominant figure shaping the artistic development of his female partner.139 In the case of Dehner and Smith, Marter has successfully challenged this troublesome paternalistic model by persuasively arguing that both artists benefited from a two-way exchange of ideas.140 In earlier publications, I have established that Smith and Dehner operated in broader intellectual circles in the 1930s and 1940s in order to correct the perception of Dehner as exclusively trapped in a dyad with Smith.141 Recognizing Boas’s contributions expands on this effort, since both Smith and Dehner were influenced by her presence, ideas, and art. Despite the many crosscurrents in these exchanges, Smith’s and Dehner’s artistic responses were ultimately independent.

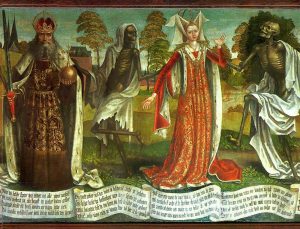

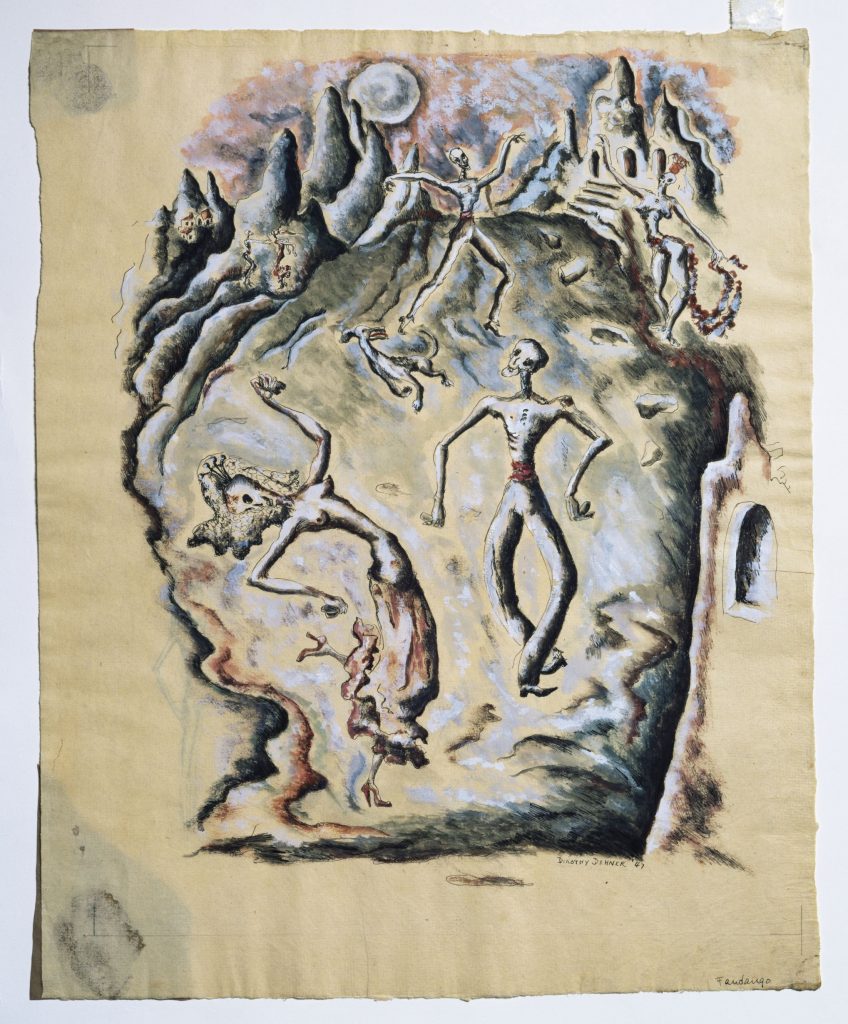

Dehner’s representation of dance communicates her version of the modern world in content and form. She uses dance to alert the audience to the dangers of lingering fascism in the postwar world, a message both Smith and Boas address around the same time. With specific allusions to Spain and frequent references to death, her themes come especially close to those of Boas’s Goya-esque. Dehner’s dance drawings are typical of her working method in these years: she filled the pages of small sketchbooks with ink and graphite drawings and produced related larger-scale and independent sheets with more elaborate, polished compositions often finished with areas of gouache and watercolor. Many of these works are dominated by stylized skeletal figures in the poses of classical dancers, gleefully completing the steps of formal dances within tortured landscapes that evoke wartime devastation. There is a macabre humor in the contrast between the precise, elegant movements of the dancers and their emaciated bodies and skull-like heads. Dehner’s titles include Fandango, Allemande, Gavotte, Gigue, Pas de Deux, Pavanne, Sarabande, and Tarantelle, all referencing traditional dances that had been codified into character dances in classical story ballets and subsequently reimagined by modernist choreographers.142 The accuracy with which Dehner depicts each named dance in her drawings reflects her intimate knowledge of the subject.143 However, in her renderings, the dances become more than a particular set of movements; they carry symbolic weight as she—a visual artist—experimented with the dancing body as her medium of expression.

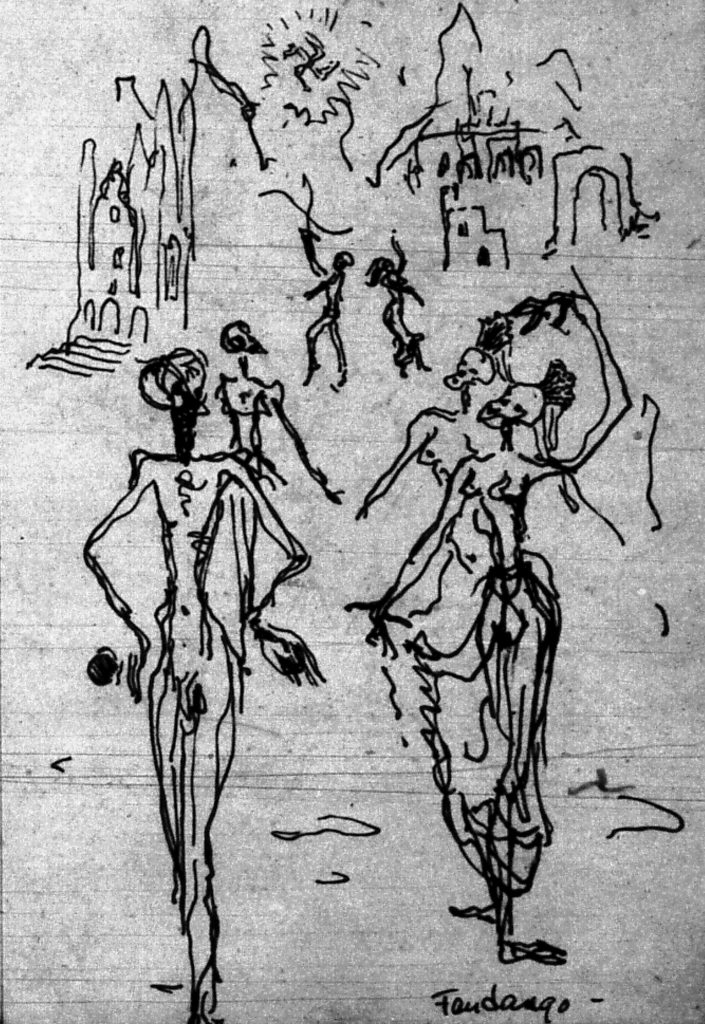

Dehner worked through her dance themes on the pages of her notebooks, trying out compositional variations and experimenting with different details. These pages sometimes offer more complex forms and overt symbolic elements than were present in the larger independent drawings intended for exhibition. As a result, the sketches provide particular insight into the meanings behind this body of her work. Especially relevant is the notebook page Dehner labeled “Fandango,” where skeletal dancers perform under a sun emblazoned with a Nazi swastika (fig. 21). In this satirical scene, fascism’s eternal presence lights a world whose inhabitants have surmounted death. Not incidentally, the Fandango is a lively dance of Spanish origin, and Dehner reinforces its cultural derivation by drawing the two female figures wearing skirts in the foreground with Spanish peinetas (traditional large combs) perched on their skull-like heads. The political content of the sketch fully overlaps with Boas’s postwar references to Spain. For Dehner, with a Marxist perspective on world events, the declaration of peace at the conclusion of World War II did not end the threat posed by fascism, which her drawings present as an enemy who triumphs even over death.

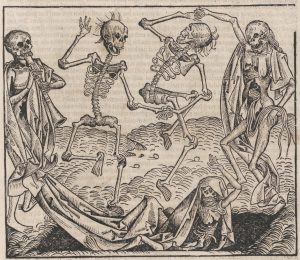

Dehner repeatedly links dance and death in this body of work, even labeling a list of specific dances she considered as subjects “Dances of Death & Destruction.”144 On one level, she references the dances of death or danses macabres of medieval mystery plays that are pictured in murals, illuminations, and prints from the early modern period.145 Dehner would have been familiar with this iconography from her wide-ranging knowledge of art history and particular interest in medieval illumination, which she cultivated around 1940. The inclusion of “destruction” in Dehner’s label was likely another indication of her association between the dances of death and war—specifically World War II—which developed a long-standing Western tradition of linking the danse macabre in Western culture with wartime or other periods of extreme upheaval.146 From its origins, the most common image of the dance of death involves one or more personifications of Death leading the living in procession toward the grave (fig. 22). Dehner’s examples specifically invoke a variation of the danse macabre in which skeletons cavort wildly, functioning for their Christian audience as a gruesome reminder of the corruptible body, as opposed to the eternal, incorruptible body of Christ (fig. 23).147 In Dehner’s political context, the well-trained, polished skeletal performers have survived the war only to occupy a battle-scarred wasteland as the minions of fascism.

In contrast to the sketchbook page labeled “Fandango,” Dehner’s formal drawing Fandango reduces the number of foreground figures to two and depicts the remaining dancers in poses of great abandon, as opposed to the precise positions in the sketch (fig. 24). Additional details of their costumes reinforce the Spanish origins of the dance and complement the speed and energy of their flamenco performance: a cummerbund and heeled boots for the male and high-heeled shoes, a flounced skirt, and castanets for the female. The skull heads of the figures indicate that their performance remains a danse macabre. The explicit anti-fascist message of the swastika-emblazoned sun has been replaced by a full moon so that the ghostly, unsettling quality to the nighttime scene takes preeminence over an overt political agenda.

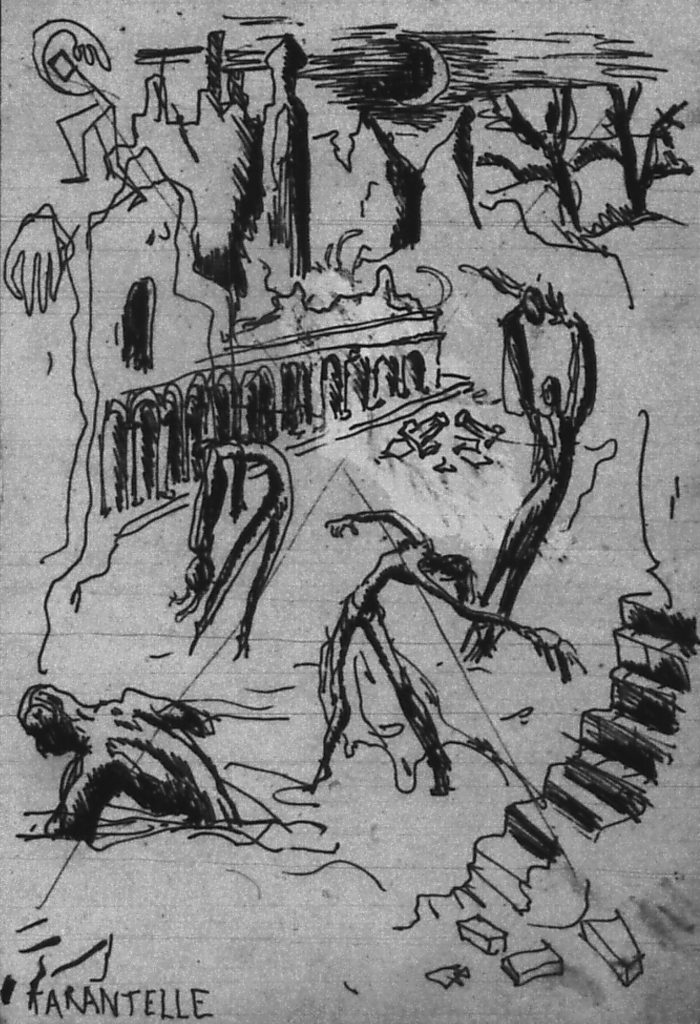

Dehner employs cosmic elements in other works in this group. In a notebook page labeled “Tarantelle,” a carefully defined crescent moon shines down on dancers moving among a town’s ruined buildings indicating war’s cataclysmic destruction (fig. 25). The classical arcade that closes off the dancer’s space simultaneously references the Italian Renaissance and Giorgio de Chirico’s pittura metafisica (metaphysical art) while providing an Italianate setting appropriate to the tarantella, an Italian folk dance.148 Notably, Italy, like Spain, was a fascist state during the recent war. But in this sketch, unlike that for Fandango, Dehner sets aside the gleeful, skeletal figures striking ballet poses in traditional costumes and portrays more conventional bodies performing a different type of movement. These four figures are thin but conventionally fleshed forms, and they proceed independently of one another, their bodies arched in forms recalling the characteristic expansion and contraction of classical modern dance. The context is still death but not the frenetic danse macabre. The figure in the left foreground emerges from the earth as do the dead in the foreground of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. Along with the fellow inhabitants of the town, this rising figure appears to suffer and mourn for his condition rather than gleefully cavort in celebration of an unnatural state. The distinctions between the bodies and movements in “Tarantelle,” as opposed to “Fandango,” suggest Dehner assigned symbolic meaning to dance styles—negative associations to traditional ballet and positive ones to classical modern dance—for it is her modern dancers who express pain, mourn the state of the world, and communicate truthfully with their audience.149 The skeletal ballet dancers are complicit in a false dynamic: they dance in a formalized fashion, maintaining their precise movements as they thwart death. Dehner employs images of modern dance to tell the truth of the state of the world, in a manner that parallels Boas’s understanding of dance.

Boas’s modern choreography embodied abstract concepts, such as Goya-esque’s reference of political abuse of power and ensuing suffering. While Dehner addresses similar themes, her images are one step removed from Boas’s abstraction in that she renders stylized images of dancers’ bodies through the medium of drawing. However, her choice of dance as subject and the meanings she conveys by contrasting one form of dance with another reveal her thinking along the same terms that define Boas’s art. Further, her representation of dance explores a relationship to space that merits examination. Dehner provides settings for the dancers that contribute to the mood of each drawing. Her dancers occupy hostile realms, desolate landscapes, or ruined towns. In the landscapes, attenuated rock formations and scraggly trees make nature threatening rather than grand, and in the cityscapes, urban debris suggests the destruction wrought by armed conflict. In addition to contributing to the mood of death that pervades these drawings, these environments oftentimes establish a stage-like space for what was, after all, a performance. The semblance of scenery is reinforced by Dehner’s use of a high horizon line combined with steep perspective that creates the effect of a raked stage for dance performances. In addition, the compositions are frequently treated as vignettes, as in Fandango, where forms cluster together in the center of the page, leaving wide, empty margins. Dehner built these images by traditional means; she marked the basic orthogonals and transversals of one-point perspective on “Tarantelle.” At the same time, her interest in dance and the stage-like space where it takes place suggests that she, like Boas and Smith, was thinking in terms of actual bodies in movement. These drawings function as her own dance-driven exploration of the relationship between two- and three-dimensional representations of objects in space. For Dehner, without question, these investigations were modern; “Suite Moderne” was the name she wrote at the top of a list of dance drawings.150

Despite the connection between modernism and truth that Dehner seems to posit, from a formalist perspective, her drawings seem removed from the advances made by other American visual artists in the late 1940s, especially the modernists generally championed in art-historical writing. It is worth recalling that the more inclusive conception of modernism evident in Dehner’s practice was in keeping with the thinking of many artists, critics, and museum professionals who did not hold with a singular, exclusive definition of avant-garde art. As such, Dehner’s distortions of scale, rejection of conventional renderings of space, and eclectic range of symbols fit the broad definition of experimental American contemporary art. In addition to these formal qualities, from her perspective, Dehner’s politicized subject matter was another legitimate component of her modernism. In the late 1940s, she shared this complex, multilayered understanding of modernism with Smith and Boas, and the critical resistance the visual artists may have faced paralleled the critique of Goya-esque as lacking “dance sense.”

In December 1948, Dehner included Tarantella and Fandango among thirty-three works in a solo exhibition at Skidmore College.151 The exhibition checklist organized works according to medium, but sandwiched between “Ink Drawings with Wash” and “Gouaches” was a third category titled “Six Drawings about the State of the World,” where the dance drawings appeared. For Dehner, the “state of the world” might recall two interconnected realms—her personal life, including the state of her marriage, and the world at large, emerging from the trauma of World War II.152 In the public context of the exhibition, the phrase likely suggested the latter. While the political message was communicated more forcefully in notebook sketches and emerged comparatively muted in the independent drawings displayed in the exhibition, by identifying them as representing the “state of the world,” Dehner asserts a specific contemporary framework for the images.

Conclusion

The anti-fascist, anti-imperialist stance Dehner shared with Smith and Boas in the years immediately following World War II was an important marker of the political perspectives of the three artists. As I have explored, modernist formal developments in dance and the visual arts were similarly intertwined in the works of the artists during these years. By 1950, the direct comradery and solidarity these three shared in the few short Bolton Landing summers had slipped away, each going a separate way. The communal dream of an annual arts festival died with the collapse of the 1949 program. Boas’s New York City school was failing, and she lost any traction she had gained toward sustaining a meaningful summer program. Her Bolton Landing school struggled along with a reduced roster of classes in 1950 and 1951 and then ground to a halt when Boas found much needed financial security in a full-time academic position at Shorter College in Rome, Georgia. There she focused on teaching dance in a liberal arts curriculum, far from the avant-garde world of New York City, although she remained directly involved in the cause of racial justice.153

The crises in Dehner and Smith’s marriage escalated in the late 1940s, with Smith’s physical violence toward Dehner precipitating significant periods of estrangement before a final break in 1950.154 Smith remained in Bolton Landing, while Dehner chose to leave her beloved farm to set off in new directions. She quickly completed an undergraduate degree at Skidmore College and eventually took up residence again in New York City. Although their paths diverged, there is ample evidence that Dehner and Smith—like Boas—remained committed to the social and political issues that so engaged them at Bolton Landing.155 However, having set aside the complex political and personal iconography evident in their work of the late 1930s and 1940s for the interior explorations typical of emerging abstract expressionism, such stances were less obvious in their subsequent artistic output.156

Still, in the final months of World War II and in the war’s immediate aftermath, Boas, Dehner, and Smith had undoubtedly shared a series of varied and sometimes intense encounters in Bolton Landing. They were drawn together by their joint commitment to making modern art shaped by their shared social and political perspectives. Their bonds were reinforced by dichotomous positions as outsiders to the rural community and leading figures in the broader art world. Collectively, they explored modernism and its limits, sought new ways to engage with communities—near and far—and challenged the social and political status quo. For this brief, fertile interlude in Bolton Landing, visual art, classical modern dance, and leftist politics were the vehicles and stimuli for creativity.