Kirsten Pai Buick

As an early subscriber to one of the ancestry websites, I hit a roadblock because I am, in large part, a descendant of enslaved people. I can trace my white ancestors all the way back to twelfth-century Europe, but when it comes to my African ancestors—whose lives and continuities had been disrupted by the Atlantic slave trade—the early iterations of those sites did not include bills of sale, and my search was therefore stymied. Such sites continue to bypass the ugliness of our collective archive by tracing “genetic ancestry” through geographies that accept borders drawn by invasion, imperialism, and exploitation as fact.

As an art historian, this brings me to the problem of commemoration and monuments. The monuments that exist in public spaces actually work to counter the fact that enslaved women gave birth to property; that modern medicine owes much to experimentation on enslaved people; and that the legacies of enslavement continue to shadow the lives of its descendants. As recent findings establish, George Washington actually harvested teeth from his enslaved people to create his dentures.1 Enslaved people existed at a complex crossroads of invaluable, disposable, interchangeable human commodities whose “labors” (work and the labor of childbirth) were exploited by a nation that has yet to fully recognize its history.2 At the heart of “American democracy” and “American freedom,” there is a shameful rot, which public monuments “labor” to paper over in order to present our struggles and conflicts as resolved and settled. The work that these monuments participate in is to tell only celebratory narratives of Confederate generals, brutal doctors who experimented on captive populations, slaveholding and openly racist founding fathers and United States presidents, and a host of similarly problematic historical figures who are excused as men of their times. How do I know that this is true? Because, despite the protestations of historic preservationists, art historians, and heritage apologists, the public spaces that these monuments have held for decades has resulted in no appreciable betterment or enlightenment of our society. Until they are threatened with removal, those monuments remain largely invisible both spatially and textually (to my knowledge, no monumental corrective has been authored by any art historian who is concerned about their disappearance). Their presence is a promise—something that we will get around to later; an opportunity to fund studies about how to curate a more balanced history around them; temporary sites of intervention and protest, and yes, lynching. They are placeholders—as we have become culture hoarders who have exchanged a dynamic and changing public space for the illusion of fixity and permanence as represented by monuments that do not and cannot represent the complexity of our histories.

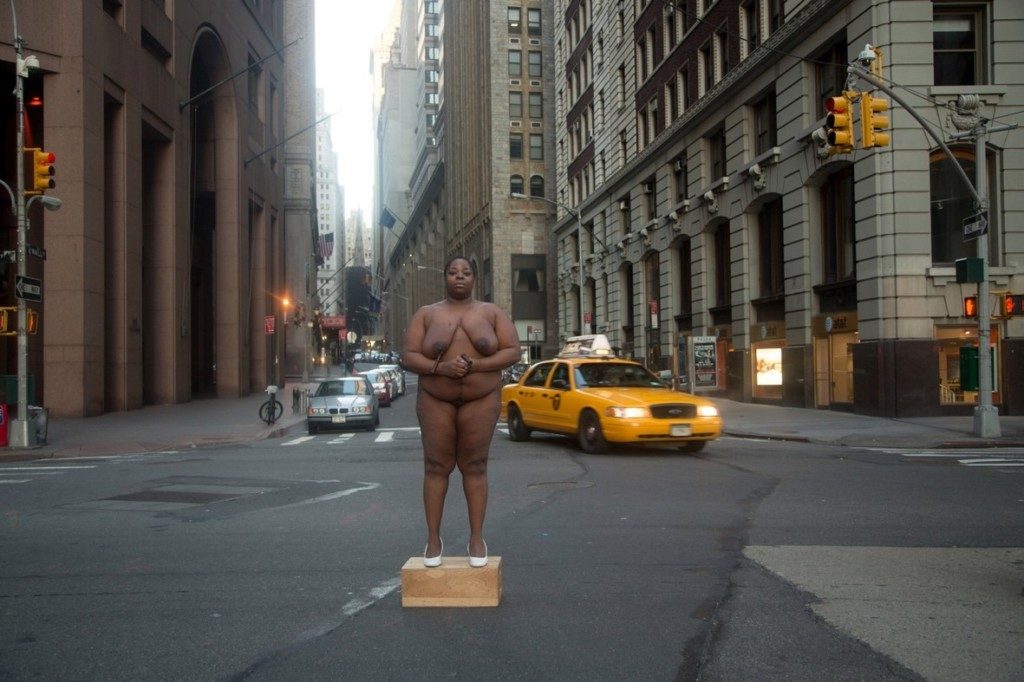

Recently, I had occasion to ponder the history of black women who were sculptors and their complex relationship to commemoration, monument making, and American freedom.3 Each artist, Mary Edmonia Lewis (1854–1907), Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877–1968), and Augusta Savage (1892–1962), revealed a deeply ambivalent and revelatory relationship to the perversity of American freedom, since the concept is diametrically opposed to and uniquely constitutive of black freedom and blackness itself. I am still learning from them; and what I call their “monumental gestures toward anti-monumentality” taught me that perhaps monuments should be temporary, mobile, difficult, in flux, and challenging to our most deeply held fictions. And I have found resolution in the work of artists such as Nona Faustine, whose White Shoe series “walks the line between the past and the present” and whose work explores “the inherited legacy of trauma, lineage, and history.”4 In the series, Faustine wears only white, low-heeled pumps and traverses the landscape that enslavement made. In her self-portrait, From Her Body Sprang Their Greatest Wealth (2013), she stands naked on a plain wooden box in the middle of Wall Street, which functioned during the Colonial period as a slave market. Her presence—silent, somber, monumental—nuances that space, which most recently has hosted empty and shallow debates about the confrontation between “Fearless Girl” (placed to honor so-called “international women’s day” and subsequently papering over the fact that, as Elsa Barkley Brown notes, “not all women have the same gender,”5 because of their lived experiences that are inflected by factors like race, geography, and class) and “Charging Bull.”6 Faustine’s photograph pays homage to the labors of enslaved African women and adds something complex to the debate about Wall Street and how to tell a history that is inclusive and complex. Her truly fearless monumental gesture toward anti-monumentality continues in significant ways the early work of African American women artists and disrupts the comfortable silences of the old public placeholders.

Cite this article: Kirsten Pai Buick, untitled essay, “Bully Pulpit,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1637.

PDF: Buick, Bully Pulpit

Notes

- Kathryn Gehred, “Did George Washington’s False Teeth Come From His Slaves?: A Look at the Evidence, the Responses to that Evidence, and the Limitations of History,” Washington’s Quill (October 19, 2016). http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/george-washingtons-false-teeth-come-slaves-look-evidence-responses-evidence-limitations-history. ↵

- Paul P. Murphy, “Homework Assignment Asks Students to List Positive Aspects of Slavery,” KYMA.COM (April 20, 2018). http://www.kyma.com/news/national-world/homework-assignment-asks-students-to-list-positive-aspects-of-slavery/732530826. ↵

- Kirsten Pai Buick, “MONU*MENT*ALITY: Edmonia Lewis, Meta Fuller, Augusta Savage and the Re-Envisioning of Public Space,” in Jeffreen M. Hayes et al., Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman, exh. cat. (Jacksonville: Cummer Museum of Art in association with D. Giles, London, 2018). ↵

- Nona Faustine {artist’s website, accessed May 13, 2018}, http://nonafaustine.virb.com/about. ↵

- Elsa Barkley Brown, “’What Has Happened Here’: The Politics of Difference in Women’s History and Feminist Politics,” Feminist Studies 18, No. 2 (Summer, 1992): 298. ↵

- Danielle Wiener-Bronner, “Why a Defiant Girl Is Staring Down the Wall Street Bull,” CNN Money (March 9, 2017). http://money.cnn.com/2017/03/07/news/girl-statue-wall-street-bull/index.html. ↵

About the Author(s): Kirsten Pai Buick is Professor of Art History at the University of New Mexico.