Genesis of the Carl Rungius Catalogue Raisonné

PDF: Harris, Genesis of the Carl Rungius Catalogue Raisonne

I began working as the curator of art at the National Museum of Wildlife Art (NMWA) in 2000. The subject matter of the museum appealed to me from the start, both on a personal and a professional level. Personally, I grew up in Wyoming, and wildlife has always been part of my life. Professionally, I was intrigued by the possibility of delving into a topic that had been largely overlooked in scholarly circles but that had an incredibly rich history in terms of artistic production. Humans have depicted wildlife ever since the first artist painted images on cave walls.

The NMWA began life as The Wildlife of the American West Art Museum, with close ties to other museums focusing on the West. The museum launched with an amazing collection of work by Carl Rungius (American, b. Germany, 1869–1959), widely acknowledged to be the finest historic painter of North American wildlife. Currently, the NMWA holds the largest collection of Rungius-related material in the United States, including paintings, sculptures, prints, and ephemera. The Rungius collection at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta, is the largest in the world. Other than that, Rungius paintings are held by museums and private collectors across the country. Abroad, there are only a few known Rungius paintings, including a strong collection at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, in Enschede, Netherlands.

As began my curatorial career, I was grateful to have the opportunity to work with leading scholars like Eleanor Jones Harvey, Peter Hassrick, Brian Dippie, and Byron Price. Seeing what they were doing to advance the recognition of Western art within the greater field of American art inspired me to try to do the same for wildlife art, at whatever level I could.

One of the first major catalogue raisonné projects I encountered was that of Charles M. Russell, with Price at the helm. Making its debut in 2007, the Russell catalogue featured a multipronged approach, including a touring exhibit, hardcover book, and online database. I remember being impressed by the scope of the project and how it demonstrated that publishing a massive, soon-to-be-out-of-date tome was not necessarily the best way to accomplish the goals of a catalogue raisonné in our digital era.

Subsequent conversations with Price about the Russell catalogue and Hassrick about the Frederic Remington catalogue produced an outline for a project that I was not sure would ever come to fruition, but one that I believed would raise awareness and recognition of Rungius’s work as it helped raise the stature of wildlife art and the NMWA. During the early 2010s, an institutional goal of the museum was to be recognized as the center for information and knowledge about wildlife art. For the museum to initiate and administer a Carl Rungius Catalogue Raisonné (CRCR) seemed like a major step toward accomplishing that goal.

In 2019, one of the eventual sponsors of the catalogue asked me if there was a project I had always wanted to tackle but had never had the resources to accomplish. I had a few thoughts in mind and went to speak with NMWA chairman emeritus Bill Kerr, asking the same question. At the top of both of our lists was a Rungius catalogue raisonné. With that idea in place and a generous sponsorship offer from both the Thomas and Elizabeth Grainger Family Charitable Fund and the Robert S. and Grayce B. Kerr Foundation, the CRCR was launched. I took on the leadership of the catalogue as a special independent project of the NMWA.

As a newcomer to such an endeavor, I was fortunate to find the Catalogue Raisonné Scholars Association (CRSA), an organization that has provided a supportive online community with numerous virtual seminars addressing topics ranging from emerging projects to digital catalogues. Through the CRSA, I was even more fortunate to find Melissa Speidel, head of the Albert Bierstadt Catalogue Raisonné, who signed on to the CRCR to help research and cataloguing.

One of the most appealing things about the digital platform is that it has the ability to allow access to research more quickly than a hardbound book. The digital platform can change the mode of the catalogue from a single event (the publication of an authoritative volume) to an ongoing process, remaining a self-conscious work in progress. The scholarly rigors of the catalogue raisonné process should not be discarded, but publishing the database when it is near completion while acknowledging that some information is still needed provides genuine opportunities. Making the resource available and asking for help to fill gaps can promote participation from collectors, dealers, and museums. We have yet to test this theory with the CRCR but plan to publish sections of the database as they near completion over the coming years.

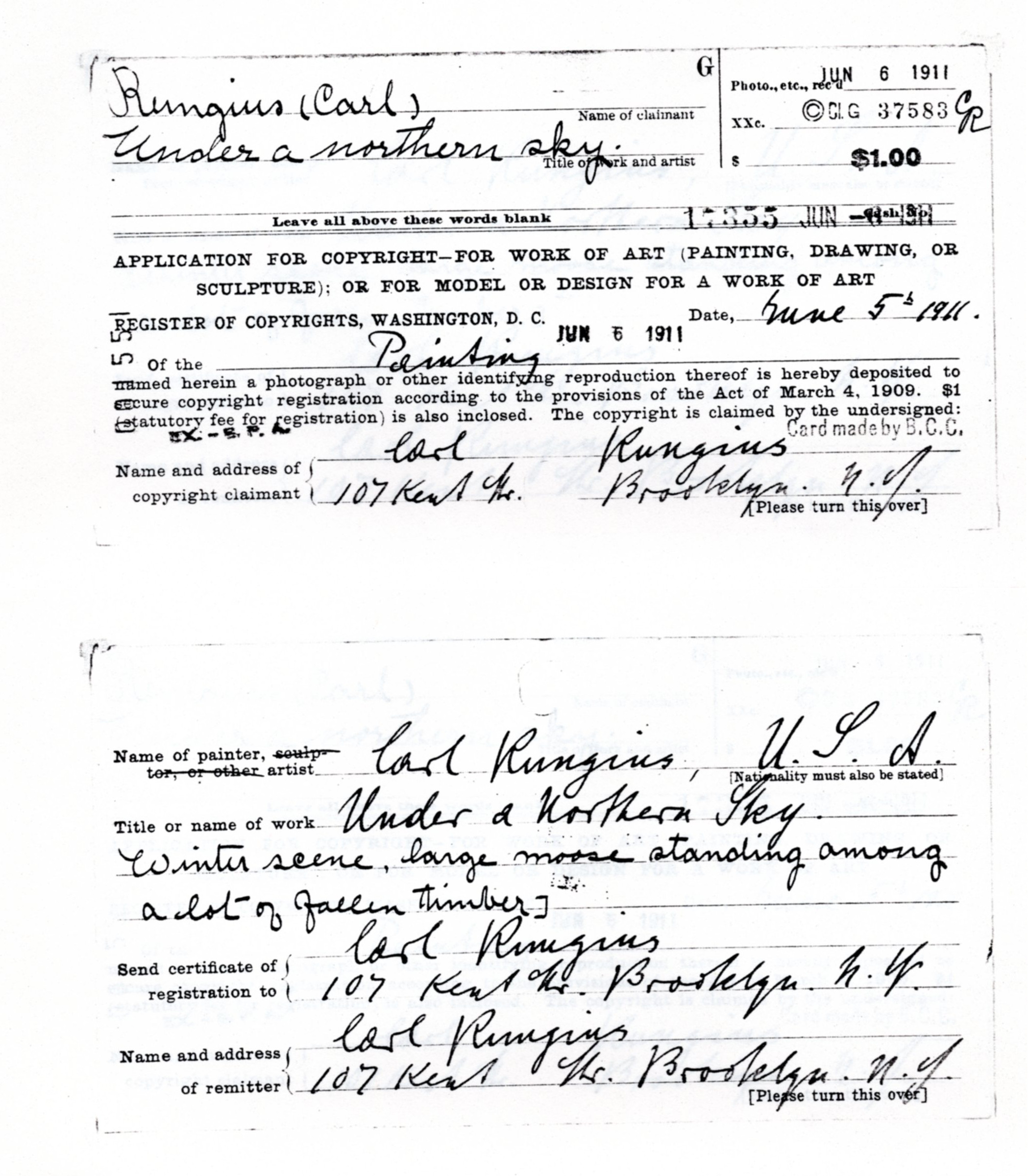

Early in his career, Rungius copyrighted a selection of his finished paintings by submitting black-and-white photographs of the works and application forms to the US Copyright Office (figs. 1–2). Numbering roughly one hundred objects, these copyrighted paintings will be the first set of records to be made available online. This set will serve as a test to see how our database is working and reveal what tweaks need to be made. The second set of records will be Rungius’s published book and magazine illustrations. The third set will be defined after we gauge the success of the first two. This model shows how the digital catalogue raisonné can have a more flexible structure, allowing experimentation with different scenarios—advancing, pausing, or even rewinding in response to various circumstances.

An important question related to digital catalogue raisonné projects is what software to use. The CRCR uses TMS Collections. While not specifically designed for catalogues raisonné, TMS has the benefit of feeding directly from the museum server to the website via another program, eMuseum. TMS Collections is also web-based, allowing catalogue workers (Melissa and me) to log in remotely from home offices instead of having to be physically at the museum. When used to its full capacity, TMS enables the kinds of linked data one would hope for in a digital platform. For example, when users pull up a record for Rungius’s Under a Northern Sky, they might see that it appeared in an issue of Forest and Stream. Clicking on the record for Forest and Stream, they can see that two other Rungius paintings appeared in that same edition and then click through to those records. Similar interactivity is possible with exhibition records and other significant fields. Another benefit of the digital platform is the ability to provide multiple images. In the case of Rungius’s copyright filings, an image of Under a Northern Sky and its completed copyright application are easy to make available. As more and better images are found, they can be added to the record and made public almost immediately.

The Henry Moore Catalogue Raisonné uses TMS Collections to its full advantage and helped us learn the best ways to leverage the robust capabilities of the program. One of the challenges of creating a digital catalogue raisonné is simply learning how to use the software. Many of our early records had bibliographic and exhibition references listed in static fields that did not allow for the interconnectivity we wanted. After learning a new way to enter the data, we then had to go back through and input this information a second time, in a different way, so that it would link to other records. As with traditional catalogues, deciding on how to format entries (MLA, Chicago, etc.) and then sticking with that format consistently is another huge challenge. Since there does not seem to be one accepted “raisonné” style, I am in favor of making each entry as readable as possible, so anyone who comes across a CRCR record will be able to understand it without referencing separate lists of abbreviations or having to know the intricacies of a particular manual of style. I hope that this will make the CRCR more accessible to a broader range of people.

It is also valuable, if the resources exist, to produce a physical book of “masterworks” or some other type of companion volume. A book highlighting the best work from a catalogue raisonné is not timeless, of course, as information on certain paintings will always change. The raison d’être of a companion book is to publish a curated segment of the artist’s oeuvre, a goal that should stand the test of time. The physical book is also a tangible object promoting the larger project that can help spread awareness of the digital initiative.

With the Russell catalogue as a model, the CRCR also takes a multipronged approach. At the end of the research phase of the project, I forecast a traveling exhibition and masterworks book to accompany the launch of the full online database. Midway through the project, we are working on an exhibition and catalogue that will help advance the goals of the CRCR. This summer the NMWA will premiere Survival of the Fittest: Envisioning Wildlife and Wilderness with the Big Four, Masterworks from the Rijksmuseum Enschede and the National Museum of Wildlife Art, which will then tour to five venues in the United States. The exhibition features Rungius paintings alongside work by three of his contemporaries, Richard Friese, Wilhelm Kuhnert, and Bruno Liljefors. The exhibit and accompanying catalogue are major separate undertakings, but, if things work according to plan, these midstream endeavors will raise awareness of the CRCR, attract new submissions, and, perhaps, help us glean more information about the paintings we already have in the catalogue.

A catalogue raisonné can play a major role in addressing greater concerns or lacunae in the field of American art. On the one hand, I am working on an understudied artist in an understudied realm of art history. One the other, I am working on a white male painter of European descent whose work was collected by members of the highest echelons of American society. For example, Theodore Roosevelt owned two Rungius paintings and one of his bronze sculptures. While, in terms of a diversity, equity, and inclusion framework, there are many additional artists in need of serious study, I believe that due to long-held prejudices in the art world, wildlife art is among the least well-studied areas of American art; researching one of its greatest practitioners, to me, has real merit. Creating a digital catalogue raisonné open to anyone provides a baseline of sound scholarship from which further research, critique, and analysis can develop. American art history can only benefit as more online catalogues are published on a wider array of artists. The current plan is to offer free access to the CRCR on the NMWA website. When it goes live, a link to the CRCR will be added to our dedicated webpage: https://www.wildlifeart.org/collection/carl-rungius-catalogue-raisonne.

Just as our catalogue hopes to raise awareness and recognition of Rungius, other cataloging projects can elevate previously understudied artists by giving them the serious attention and rigorous study afforded to better-known art-world luminaries. With the ability to publish the results online, new catalogues can be more accessible to a broader audience than hardbound books, which are often expensive to produce and can be difficult to locate or borrow. A less-formal vision of what a catalogue raisonné can be also makes it (potentially) less costly and more open to a wider range of scholars working on more diverse artists. Only time will tell in what new directions the digital catalogue raisonné will take us.

Cite this article: Adam Duncan Harris, “Genesis of the Carl Rungius Catalogue Raisonné,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17343.

About the Author(s): Adam Duncan Harris is the Grainger/Kerr Director of the Carl Rungius Catalogue Raisonné.