Commemoration of an Epoch: Monuments to the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the United States

Editors’ Note: This article is the first of three digital art history projects generously funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art. The second and third installations of this project will appear in our Fall 2022 issue (number 8.2) and Fall 2023 issue (number 9.2).

Introduction

Upon the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, the artist Adelaide Johnson (1859–1955) reflected on the symbolic importance of her sculpture Portrait Monument: “No one seems to have arisen to the realization that this is something far more than the simple presentation of three busts. It is the commemoration of an epoch.”1 With this, Johnson affirmed the significant role monuments play in memorializing the history of the suffrage movement. Portrait Monument, which honors Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton (fig. 1), was sponsored by the National Woman’s Party and—at the time of her statement—was soon to be dedicated in the US Capitol.2 The sculpture includes half-length busts of each woman, and although they are all roughly the same size, Johnson angled them at different heights, with Stanton slightly higher than Mott and Anthony slightly higher than Stanton. The subtle elevation of Anthony in relation to her companions suggests her heightened importance in the movement. The base from which the busts emerge was left unfinished, and to drive home the statue’s symbolism Johnson included a rough-hewn tapering projection rising from the base behind the busts. She explained that she deliberately left the pedestal and background incomplete “because their work is still unfinished.”3

Johnson’s Portrait Monument is representative of a number of issues related to public monuments to women’s suffrage. The depiction of three white activists concretized the persistent marginalization of women of color in both the movement and its commemoration. Its stolid, unexpected form, sculpted by a woman artist, presaged the coming challenges to traditionalism in public monuments. The monument’s very unfinishedness reflected the evolving public understanding of the women’s movement it celebrated, and, like the movement itself, it was undermined almost immediately. Its placement in the Capitol Rotunda was a nod to the growing influence of women in public life, but just twenty-four hours later—at the behest of a cadre of male politicians—it was unceremoniously moved to the Crypt, a space far less visible and eminent. Here it earned the derisive nickname “Three old ladies in a bathtub.”4

The study of public art in the United States—including the ways in which it is funded, commissioned, and placed; which subjects it takes up; and who makes it—is rife with the same gender and racial inequalities present in other cultural and political arenas. According to an oft-repeated statistic, a mere 10 percent of the more than five thousand monuments in the United States honor women.5 My research, however, reveals that the actual number is much lower, with only 6 percent of all US monuments taking historical women as their subjects. As the writer Rebeca Solnit observed in “City of Women,” “A horde of dead men . . . haunt New York City and almost every city in the Western world.”6 These men stand high on pedestals, making the public literally and figuratively look up to them. Women, on the other hand—long shut out of the traditional hero-making professions of president, statesman, general, or explorer—have few paths to ascend that plinth.

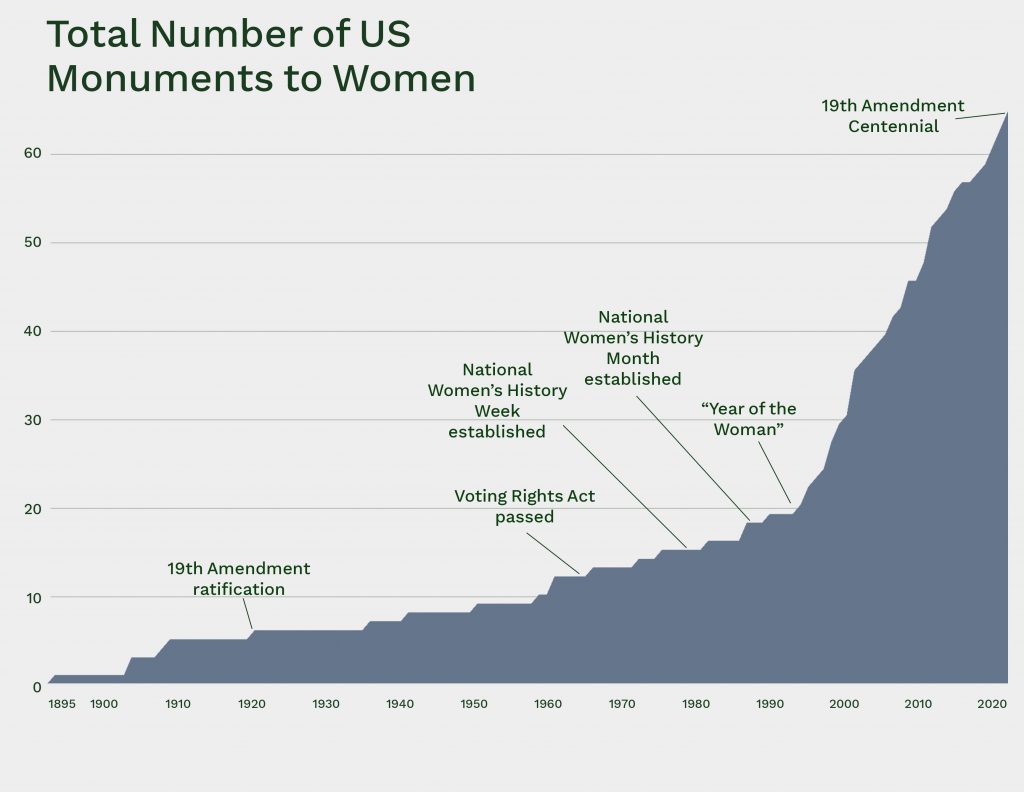

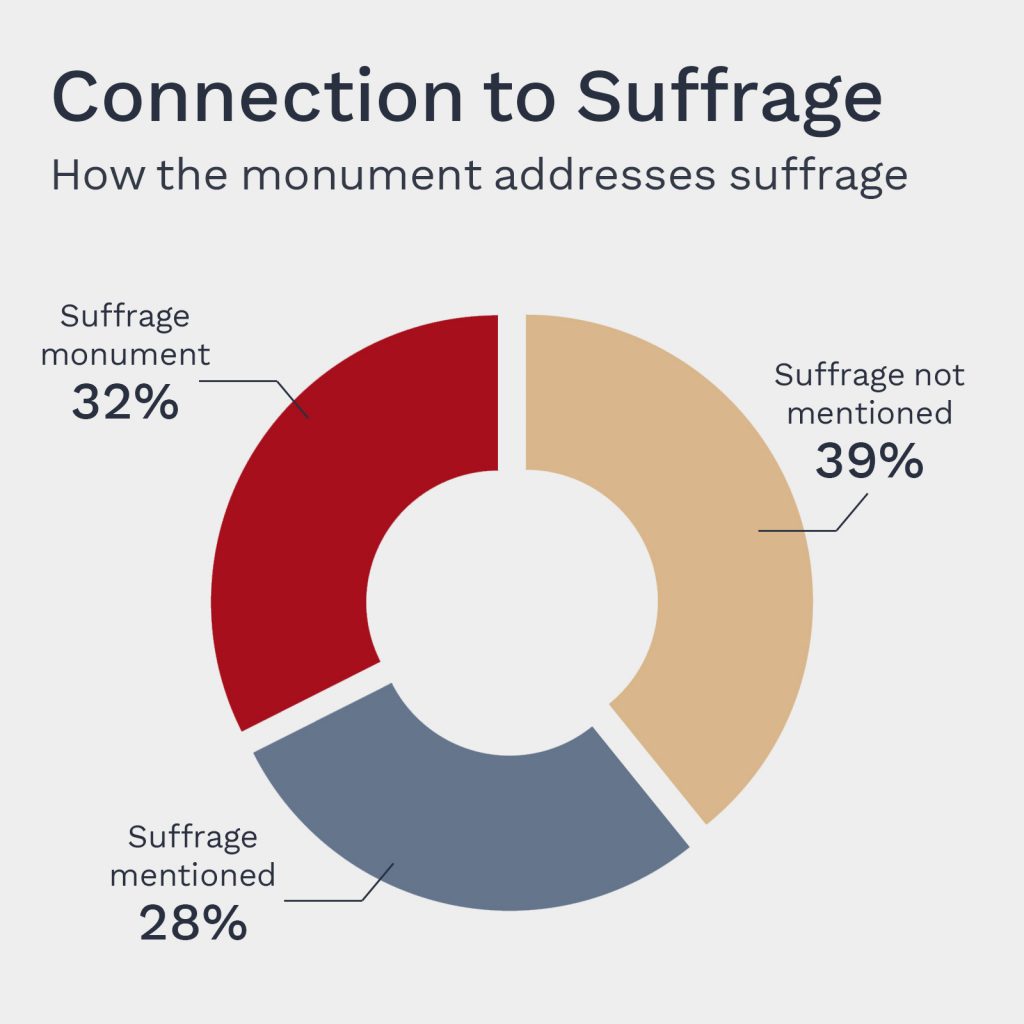

Following the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, affirming a woman’s right to vote, individuals increasingly recognized the importance of public commemoration to solidifying and legitimizing the achievements of women.7 A century later, many of the monuments in the United States recognizing women take suffrage as their subject. This article and corresponding datasets (fig. 2) cast new light on the nation’s seventy-five monuments that honor the suffrage movement and its actors. As the visualization in figure 3 illustrates, efforts to memorialize the movement sharply accelerated in the 1990s—fueled by public history initiatives, which sought to popularize women’s history and position suffrage as a central concern—and peaked on the eve of the amendment’s one hundredth anniversary (fig. 3). The 2020 centennial and its accompanying flurry of monument-building also coincided with a national and international reckoning about public monuments, historical authority, and representation.8

Fig. 2. Suffrage Monuments in the United States. Click “Enable map scroll” to navigate and zoom in and out.

Click individual map icons for expanded information. Click “ArcGIS map” below to open map in new window.

ArcGIS map

Full dataset

More on the map icon

The existing scholarship on public monuments tends to present contextual and historical readings, but a paucity of data.9 With a few exceptions, suffrage monuments have been understudied and underresearched in art-historical discourse.10 Such an oversight is tied to a lack of documentation of the artworks, their “localness,” their frequent employment of traditionalist styles, their tendency to take the form of bronze portraits, and their creation by artists who worked outside major metropolitan art centers. Whereas art-historical essays typically focus on one or two key objects of study, this article takes a bird’s-eye view. By broadening the scope of research to include all the suffrage monuments made over the last one hundred years, I have uncovered patterns and trends in the commemoration of the suffrage movement. This data-driven analysis unearths monuments that have received little attention, reveals an evolving narrative of the public commemoration of women, and demonstrates how the methods of the digital humanities can enhance the study of art.

This methodology looks at suffrage monuments as a distinct collection of artworks, one that tells the story of how the suffrage movement has been perceived or misperceived and subsequently concretized in public spaces. For the purposes of this study, a suffrage monument is defined as a built form that either commemorates the movement broadly or takes as its subject those historical figures who had a significant relationship to the movement. This also includes women who interfaced with suffrage but were not explicit suffragists (see the appendix for an explanation of methodological approach and scope of data collection). Approaching this assemblage of monuments quantitively, as well as qualitatively, this essay demonstrates that the works do not cohere around a singular, linear narrative of suffrage. Instead, they reflect the fractious, uneven, and unfinished history of the movement, dramatize popular stories, and both contribute to and challenge the processes of myth creation. As this essay will show, suffrage monuments in the United States vividly illustrate the power of art to shape public memory writ large.

This article is organized into five sections, each answering with data and case studies a previously unanswered question about the commemoration of women’s activism and suffrage. Section 1 establishes the popular narrative of the suffrage movement and considers the monument’s role in the construction of public memory. Section 2 investigates the subjects of the monuments: what and whose histories are being told in these monuments, and how do race and ethnicity inflect commemoration? Section 3 traces a timeline of suffrage monument-building: when were these monuments built, and what was the context in which they emerged? Section 4 concerns the site of suffrage monuments: what is the relationship of a monument to its location, and how has the regional concentration of suffrage commemoration affected an understanding of its geographic borders? The final section addresses the style of suffrage monuments to consider the artists of these monuments and the visual vocabularies they are engaging. Underlying each section is also a shared question, perhaps harder to answer than the others but no less significant: what impact do these monuments have on audiences? To address these inquiries, this essay calls upon a comprehensive catalogue of US monuments related to suffrage: data on the subject, location and style of the monument, and the gender and location of the artist at the time of their birth and at the time of their statue’s dedication. Data-rich interactive maps and charts drawn from this information showcase findings, forming an essential companion to this article. Such visualizations are indispensable, as they elucidate patterns that only emerge in the aggregate. Simultaneously, this article offers a qualitative history unavailable through looking only at the charts and maps. Taken together, these complementary tools—article, maps, and charts—situate the suffrage monuments in temporal, spatial, and statistical relationships and uncover how women are (and more frequently are not) recognized in public spaces.

The data lays bare historical absences and erasures. As suffrage monuments incorporate some women into the larger histories of the United States, they omit others. Perhaps expectedly, historical commemorations often centered the contributions of white women, leaving Black, Asian, Hispanic, and Indigenous women on the margins. This project quantifies inequities in representation by visualizing these disparities. Read together, the monuments comprise a metatext of historical memory and suffrage canonization. Their study uncovers how the legacies and contemporary implications of suffrage are understood, negotiated, and contested in metal and stone across the US landscape.

Popular Narratives of the US Suffrage Movement: Monuments as Public Memory

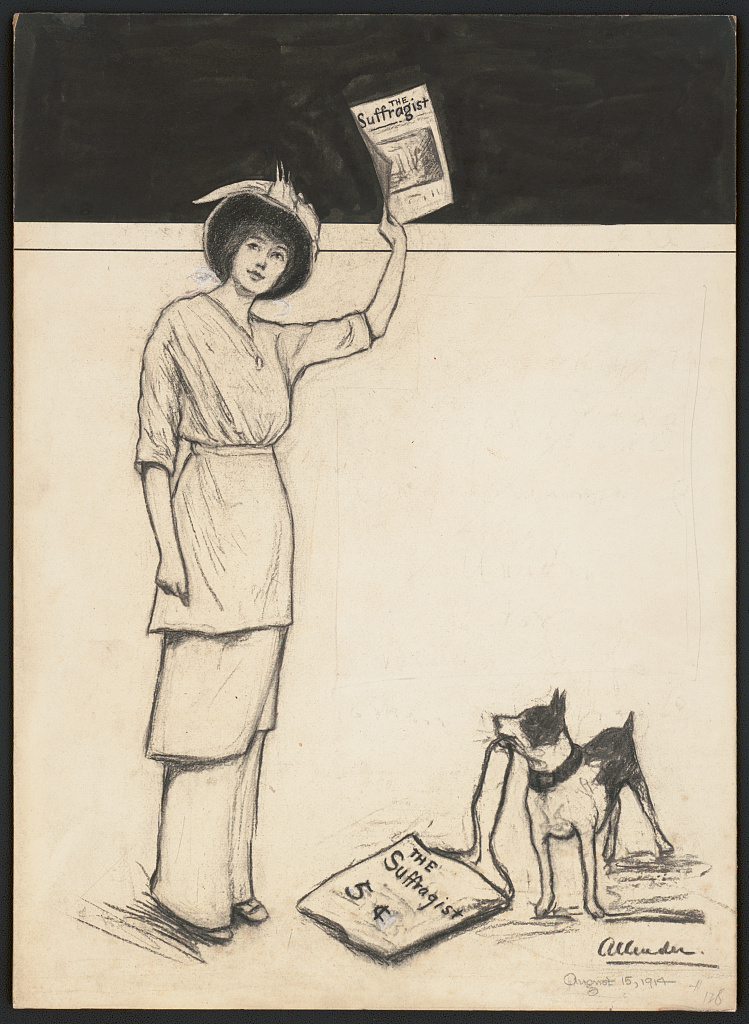

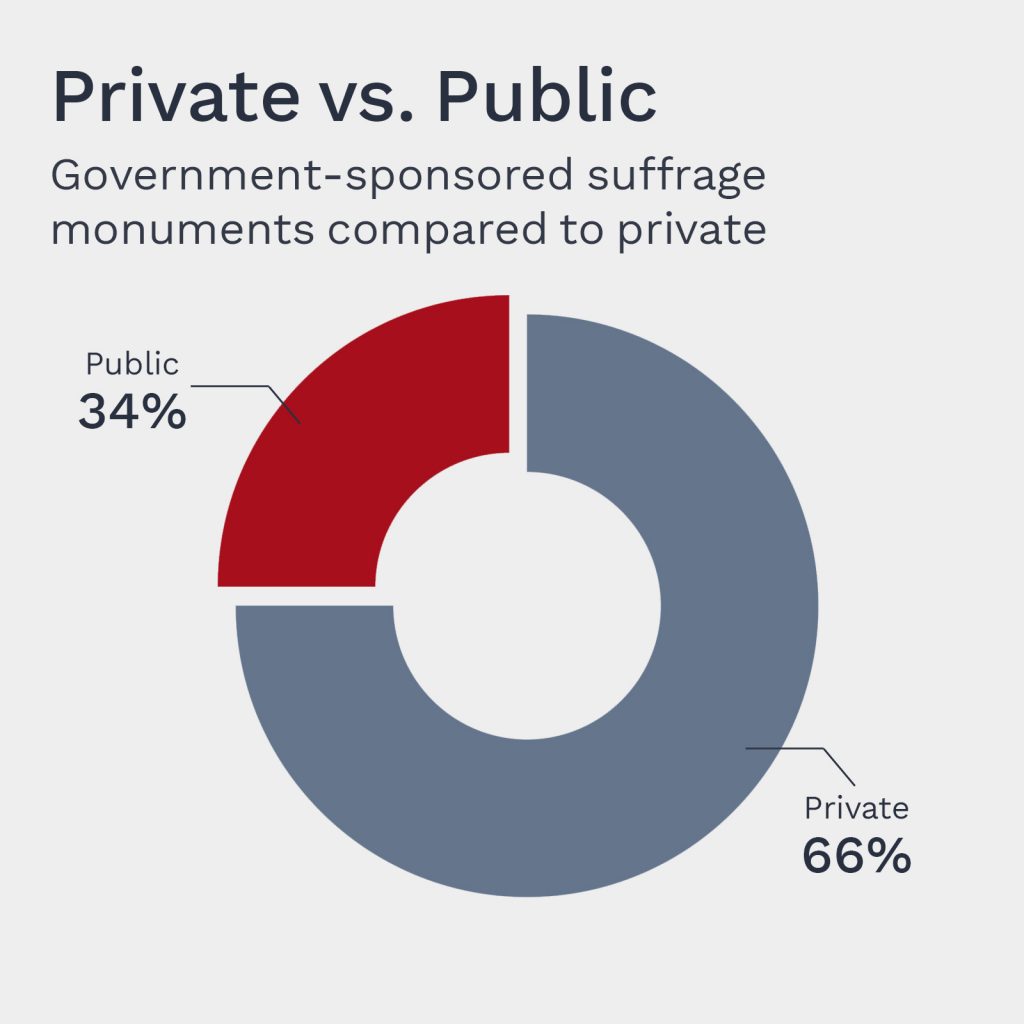

Monuments are powerful visual, material, and cultural forms of public memory. They consciously and unconsciously shape the ways viewers understand history.11 As the historians Renee C. Romano and Leigh Raiford explain, “Memory is the use of history by a wide range of constituencies primarily outside the academy.”12 Although public memory is an expression of many different publics, it is rooted in the production of history. In the United States, monument-building is traditionally a decentralized activity. Monuments are erected across the country, spearheaded by different publics both private and public (fig. 4), and span centuries. They comprise what the sociologist Paul Connerton termed a “topography of remembering.”13 Suffrage monuments, specifically, play an important role in shaping how publics come to understand the suffrage movement. Their form, subject, and location are directly affected by the active construction of the movement’s history during and since its peak. Dominant narratives shape commemorations, and in turn commemorations inflect dominant narratives.

To understand this relationship, we must first review the master narrative of the US women’s suffrage movement.14 Popular understanding marks its inception with the “first” women’s rights convention in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York, organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1887) and Lucretia Mott (1793–1880). Over two days in July, three hundred women and men considered a range of issues facing women in the United States. At the end of the meeting, sixty-eight women and thirty-two men signed the landmark Declaration of Sentiments. Phrased in the language of the Declaration of Independence, the document demanded that women “have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of the United States.”15 The convention adopted eleven resolutions, the most controversial being the ninth, which declared that “it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.”16 With these words, according to the pioneering historian of woman’s history Gerda Lerner, participants in the convention inaugurated the women’s suffrage movement.17 The movement gained momentum in the 1850s but stalled during the Civil War as women’s rights activists curtailed their work toward suffrage to lend their support to the war effort.18

Following the war, debate over the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would bar states from voting discrimination based on race, reignited discussions over citizenship and voting rights, dividing abolitionists and women’s rights activists. Some women’s suffrage activists, such as Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906), refused to support the amendment because it excluded women. Others, such as Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) and Lucy Stone (1818–1893), argued that Black male enfranchisement was a higher priority than women’s rights and that tying it to female suffrage endangered the amendment’s passage. The resulting schism divided the women’s suffrage movement. In 1869, the pro–Fifteenth Amendment faction, led by Stone, formed a group called the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The AWSA tied the pursuit of a woman’s right to vote to a broader agenda of equal rights and pursued suffrage on a state-by-state basis. That same year, Stanton and Anthony founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) to exclusively focus on suffrage, advocating a universal-suffrage amendment to the US Constitution.

After the Fifteenth Amendment passed in 1870 with no provisions for gender, the suffragist movement, now led by the AWSA and NWSA, resumed its efforts, focusing on both national and state-by-state efforts. By 1896, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Idaho had awarded women the right to vote. Washington, California, Arizona, Kansas, Oregon, Montana, and Nevada followed by 1914. In 1890, the AWSA and NWSA merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), which advocated achieving women’s suffrage by portraying women as respectable citizens worthy of the vote. In contrast, splinter groups such as the National Woman’s Party (NWP), founded in 1916 and led by Alice Paul (1885–1977), employed more confrontational strategies, including hunger strikes and pickets, to drum up publicity for the cause. The NWP’s radical tactics and the NAWSA’s effective organizational structure proved successful, and on August 18, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution was ratified, officially granting women the right to vote in the United States.

This tidy victory narrative, beginning in Seneca Falls and ending with the Nineteenth Amendment, has been challenged by numerous scholars. The historian Lisa Tetrault, in her study of the making of the “myth” of Seneca Falls, argued that the movement, in fact, had no single point of origin.19 The framing of the Seneca Falls convention as the inception point for an organized effort toward suffrage was carefully constructed by Stanton and Anthony, along with Matilda Joselyn Gage and Ida Husted Harper, in their coauthored six-volume tome The History of Woman Suffrage, published between 1881 and 1922.20 The authors had three main goals: to craft a narrative of triumph; to unify branching contingents of the movement in the post–Civil War years; and to help establish the record of suffrage in their favor.21 The National Women’s Party took up this myth in the years leading up to the Nineteenth Amendment, and the effects of this triumphalist narrative on public perceptions of the movement were felt long after the amendment’s passage.

Such historical revisionism served to solidify suffrage as having always been the primary goal of the movement. As Tetrault explains, however, “suffrage was not the sum total of women’s rights activism during this period, a fact often overlooked because of the sway of Seneca Falls’ origin tale, with its exclusive focus on the vote.”22 This focus condensed the broad spectrum of issues the movement addressed, including the social and institutional barriers that women faced, racial violence, family responsibilities, and a lack of educational and economic opportunities.

The paradigm of tying Seneca Falls to the Nineteenth Amendment also ignored the ongoing activism of Black women such as Ida B. Wells (1862–1931), who were an integral force within the movement and for whom suffrage remained a concern long after the amendment’s ratification. The amendment might have accorded women the right to vote, but Black women continued to be disenfranchised by state laws that barred voting based on race. In “The Politics of Black Womanhood, 1848–2008,” the historian Martha S. Jones contextualized the work of Black women within a broader history of activism, one in which women’s suffrage was tied to a myriad of other issues: “Following the trail of Black women’s activism leads to new insights about where and in what sorts of organizations the work of women’s rights and campaigns for suffrage can take place. . . . Campaigns for Black women’s rights were linked to their concerns about slavery, abolition, citizenship, and the vote, challenges to Jim Crow and lynching. . . . They would never limit themselves to a stand-alone set of women’s concerns.”23 Jones incorporates Fannie Lou Hamer (1917–1977) and Michelle Obama (b. 1964) into the history of women’s suffrage, demonstrating the potential for a more expansive history of the women’s movement, one that encompasses the broad intersectional political and social reform work done by women in the United States across time and place.

As such examples illustrate, history-telling and mythmaking were central strategies employed by activists leading up to and following the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Public monuments were an essential part of that memory campaign, historically and today. The architectural historian Dell Upton, in his consideration of Confederate monuments, contends, “Monuments are components of expansive landscapes that, as a group, tell stories and narrate origin myths.”24 This context, Upton goes on to argue, can be understood by analyzing monuments as a single assemblage and placing them in relation to one another. Such a relational approach is particularly helpful in animating the temporal contours of suffrage memory: how the movement was defined by its participants, how that memory has evolved over time, and how the movement continues to be remembered today. Exploring these questions elucidates how public monuments contribute to the construction of popular suffrage narratives and, in turn, how monuments are shaped by those narratives.

Simple Stories of Complicated Times: How the Formal Limitations of Monuments Impose a Skewed Narrative of Suffrage Subjects

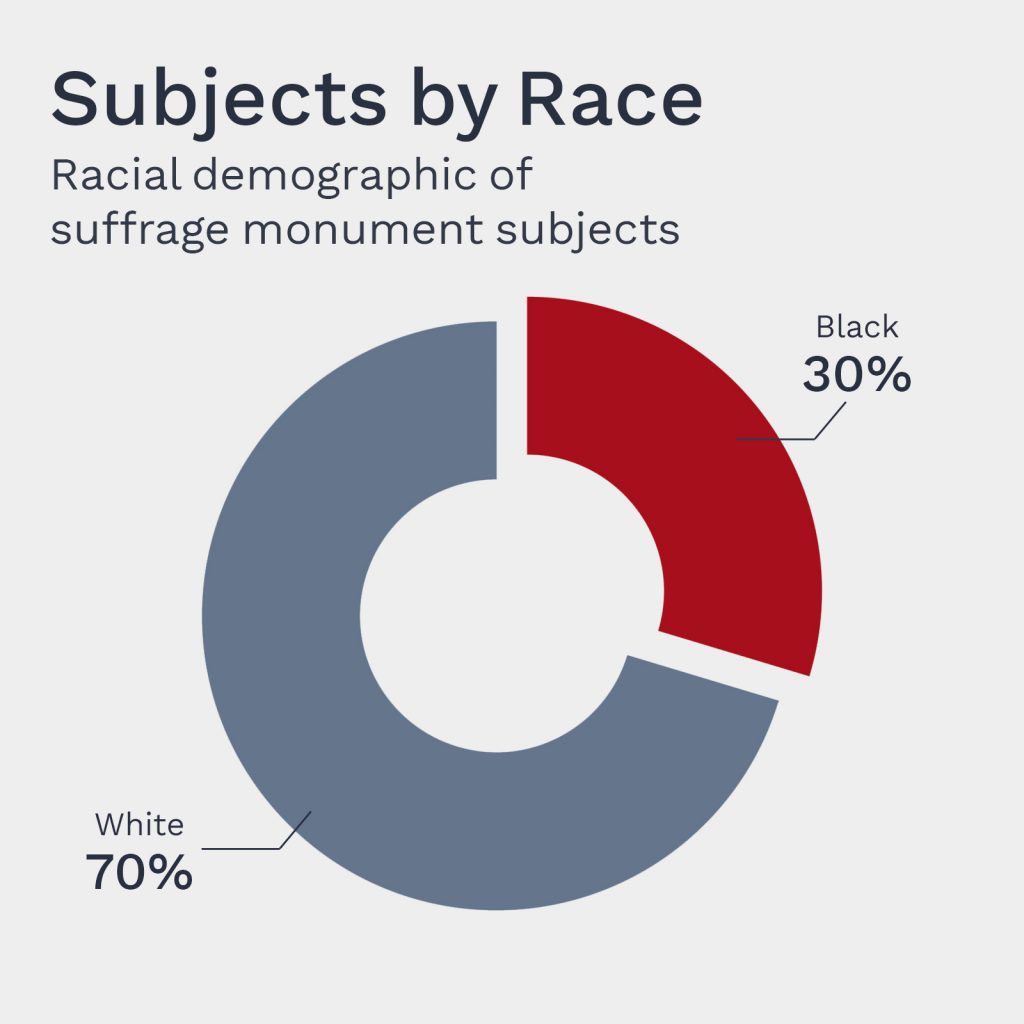

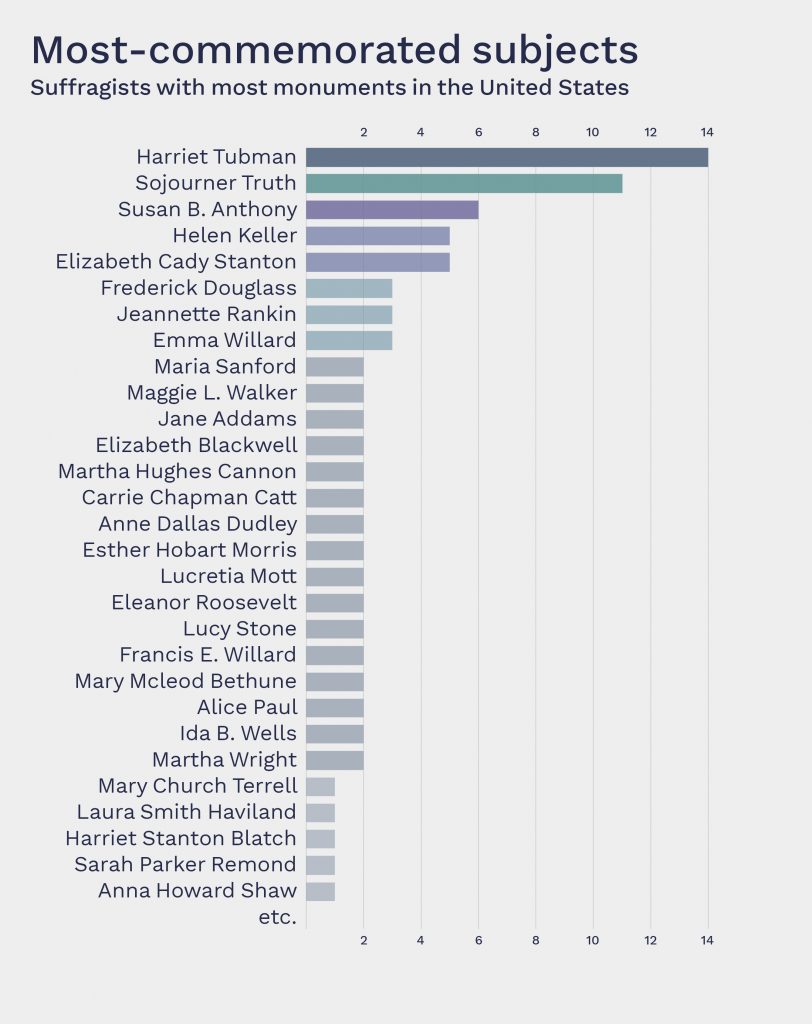

The writing of public history, as seen in the work of Stanton and Anthony, is necessarily reductive, relying on politicized elisions and streamlined narratives. Similarly, building public monuments is a process of selective narrativization, one that begins with the choice of a subject. To answer the question of whose histories are being told in these monuments, it is important to look at the demographics of who is and is not being honored. In the seventy-five suffrage monuments in the United States, eighty-nine individual subjects are represented. White women comprise 70 percent of the subjects in this dataset (fig. 5); Black women comprise the remaining 30 percent. Although not equal, 30 percent representation could be read optimistically, except that it is attributable primarily to the depiction of just two subjects: Harriet Tubman (1822–1913) and Sojourner Truth (1797–1883) (figs. 6 and 7). These women have twelve and nine monuments respectively, with two more in progress for each, making them among the most commemorated women in the United States. Although the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have witnessed an increase in the number of sculptures that depict Black subjects such as Tubman and Truth, there are still no monuments honoring Indigenous, Latina, or Asian American suffragists.25 The racial demographics of suffrage monuments align with the demonstrably false history of the movement as primarily led by white women.

Fig. 7. Monuments to Black women suffragists in the United States

ArcGIS map

Although there are no monuments dedicated to Indigenous suffragists, there is one key stipulation worth noting. Western suffrage organizations at the turn of the nineteenth century commissioned commemorations of historical Indigenous women, such as Sacajawea, the Lemhi Shoshone woman who accompanied Lewis and Clark as a guide on their journey. Such commemorations aimed to bolster the cause of women’s suffrage in the West by tying it to regional history.26 In one illustrative example, the Oregon Equal Suffrage Association sent a bronze statue of Sacajawea by Alice Cooper (1875–1937) to the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland.27 The Association used Sacajawea as evidence of the important role women played in US history, positioning her as a pioneer of the burgeoning women’s movement. Framing Sacajawea as a sister in the fight for voting rights was particularly paradoxical given that Indigenous men and women in the United States could not vote until the 1924 passage of the Indian Citizenship Act, which conferred US citizenship on Indigenous peoples. Because Sacajawea did not herself participate in the movement, and the story of a short period in her life was merely adopted by suffragists, sculptures of her are not included in the dataset.

A simple demographic breakdown of monuments by way of race and ethnicity elides the more pernicious way in which public monuments as material forms contribute to a reductive history of the suffrage movement. Monuments typically recognize only one aspect of a woman’s (often lifelong) activism. As Tetrault and other historians have argued, suffrage was often not the sole issue for the women who participated in its movement. Women such as educator Mary McLeod Bethune (1875–1955), temperance leader Frances E. Willard (1839–1898), doctor Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910), conservationist Marjory Stoneman Douglas (1890–1998), and disability rights activist Helen Keller (1880–1968) all supported the right of women to vote as part of larger social advocacy work. Being multiply subjugated, women fought on simultaneous fronts, including against racism, classism, ableism, and other forms of discrimination. And yet, monuments frequently represent their subjects in a manner that highlights just one specific element of their lived experience or their activism. The tradition of the “single-issue” monument has had a particularly harmful effect on the racial segregation found in suffrage commemoration, as Black women activists, with the exception of Tubman and Truth, are rarely recognized.

Tubman, a woman whose political life defined intersectionality long before the term entered the discourse, is honored with monuments that too often narrow her life and legacy for the sake of historical legibility. Significant to this study is the fact that—while Tubman was an active suffragist—none of the twelve monuments honoring her are explicitly dedicated to commemorating her work in that struggle. Monuments such as Alison Saar’s (b. 1956) Swing Low: Harriet Tubman Memorial (2008) (fig. 8) in New York City illustrate how Black women are largely understood through the lens of abolitionism, foreclosing a more expansive view of their multiple spheres of influence and activism.

Like many Black activists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Tubman was deeply involved in political and social movements beyond abolitionism. Born enslaved, she escaped to Philadelphia in 1849. It is believed that Tubman returned to Maryland thirteen times to personally liberate more than seventy enslaved people and help an additional fifty find freedom using a network of safe houses known as the Underground Railroad.28 During the Civil War, Tubman served the Union army as a nurse, cook, and spy. Following emancipation, she supported suffrage, giving speeches in Boston, New York, and Washington, DC, and appearing at local and national conventions into the early 1900s.29 She established a home and hospital for aged, orphaned, and sick Black Americans in Auburn, New York, where she lived until her death in 1913.

Despite her active postwar life as a humanitarian and activist for women’s suffrage, in the public memory Tubman is primarily framed as the great Black liberator.30 Monuments dedicated to Tubman confine a long life of social activism to her time as conductor of the Underground Railroad. Swing Low literalizes this by depicting Tubman as the train itself. Located in Harlem in New York City, the monument was part of a city-revitalization project intended to beautify and enrich the surrounding area and boost tourism to the neighborhood.31 It belongs to a suite of monuments to Black historical figures called the “Harlem Gateway” that roughly maps the boundaries of the neighborhood (fig. 9). Former state senator Bill Perkins championed the sculptural project during his time on the New York City Council, describing the collection as “a symphony of statues of these historic heroes and heroines to help future generations remember their contributions and sacrifices.”32 As Perkins suggested, subjects were not necessarily connected to local history, but rather to the demographics of present-day audiences, which at the time were primarily Black Americans. Tubman never lived in Harlem, yet her sculptural presence was used to reflect the contemporary community.

Fig. 9. Monuments in Harlem to Black historical figures and population demographics

ArcGIS map

Saar’s monument is a thirteen-foot-tall, fourteen-foot-long bronze sculpture depicting a larger-than-life Tubman charging forward with fists clenched. Saar (who is the daughter of acclaimed assemblage artist Betye Saar) is a Los Angeles–based sculptor and mixed-media artist whose practice addresses African diasporic and Black female identities. Saar illustrates Tubman’s inseparability from the Underground Railroad by portraying her body as a train.33 With the transportive force of a railroad, Tubman’s figure literally uproots the ground on which she walks. Leaving entangled roots in the wake that extends from the back of her skirt, the sculpted body appears to move, a testament to Tubman’s strength and determination in the face of seemingly impossible obstacles. Saar explained that the roots reference both “the pulling up of roots by slaves as they leave all behind, and Tubman’s uprooting of the slavery system itself.”34

Saar incorporated African and African American cultural and spiritual imagery into the statue. The title Swing Low invokes the nineteenth-century spiritual and its refrain: “Swing low, sweet chariot, coming for to carry me home”—a song that was sung by enslaved men and women as an expression of community solidarity and inspiration during the ongoing fight for freedom.35 The design reflects cultural narratives associated with Tubman, interweaving biographical lore and vernacular objects. Tubman’s skirt is patterned with an inventory of items that formerly enslaved people carried with them during the journey north: worn shoe soles, tools such as a knife and scissors, mementos including a locket and pipe, the herbal remedies of lily root and licorice root, and cowrie shells for good luck. The skirt also features faces, some based on passport masks from West Africa, which are believed to grant carriers safe passage in the afterlife, and others representing the men, women, and children Tubman led to freedom. Broken shackles are a symbol of freedom, indicating the emancipation of enslaved people via the Underground Railroad.

Tubman is depicted more than any other woman in the dataset. She is the subject of thirteen monuments, all of which depict her as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. None of them foreground other points in her long life. Saar’s statue responds to the particular conditions of its site in Harlem, as well as to the terms of the commission, which stressed Tubman’s role as a Black leader. Nonetheless, by conflating Tubman’s legacy with that of the Underground Railroad, and by literalizing this connection by making her body a vehicle of conveyance, Swing Low contributes to what the historian Milton Sernett describes as an “overdetermined” view of Tubman, one that eclipses the full scope of her long life’s work, including her efforts on behalf of women’s suffrage. Tubman’s contributions to women’s suffrage, however, will soon be recognized with the dedication of Ripples of Change, scheduled to be unveiled in 2021 in Seneca Falls. The monument, designed by Jane DeDecker (b. 1961), will honor women who are underrepresented in the history of suffrage by featuring Tubman alongside Laura Cornelius Kellogg (a member of the Oneida Nation), Martha Coffin Wright, and Truth.36

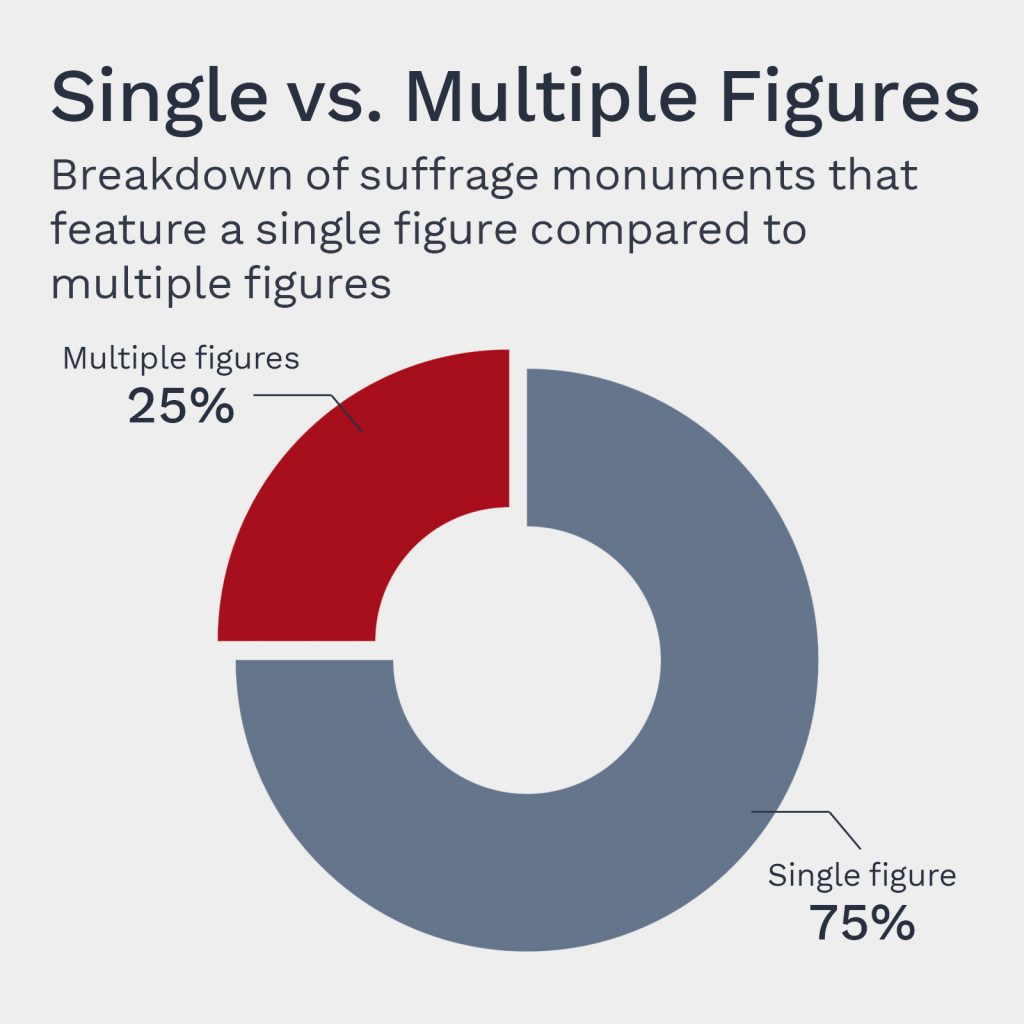

DeDecker’s proposed design, which honors multiple subjects within the space of one monument, offers a possible solution to the reductionism of the public monument and its single-issue focus. The multisubject monument has the potential to complicate and expand public understanding of suffrage history in two ways. First, such a model provides opportunities to include a greater diversity of figures associated with the movement. Second, the monument undercuts the “great man” theory of history, which posits that history is the product of distinguished and important men who should be recognized for their own unique achievements.37 The formal strategy of a figurative monument—elevating a single person on a pedestal—is the aesthetic substantiation of this paradigm, crediting sweeping historical changes to a single person.38

Twenty-five percent of suffrage monuments feature more than one subject (fig. 10). Although a smaller percentage, it is not insubstantial. Several models are employed in such multisubject monuments. One model contextualizes the suffrage movement within the larger scope of women’s history by situating individual suffragists within larger networks of political and social action that occurred over time. This strategy is endorsed by the She Built NYC Committee, a public art campaign launched in 2018 by the City of New York that aims to increase the number of monuments honoring women and people of color in the five boroughs.39 The committee unanimously agreed that the city should honor groups of women “rather than individuals, to make the salient point that history is never changed by one individual alone, that changes take time, and that women are known to work collaboratively.”40 Examples of this strategy are found in Virginia Women’s Monument (2019; Richmond), which will feature a total twelve women from four hundred years of Virginia’s history, including Jamestown colonist Anne Burras Laydon (c. 1594–1625), Pamunkey chief Cockacoeske (fl. 1656–1686), and first lady Martha Washington (1731–1803), as well as suffragists Maggie L. Walker (1864–1934) and Adele Goodman Clark (1882–1983). Seven of the twelve statues have been unveiled to date.

A second model focuses on suffrage but showcases more than one suffragist pictured together. In this form, the suffrage movement is not condensed to one woman but conceptually echoes She Built NYC’s contention that “history is never changed by one individual alone.” One such subject who has been honored in groups of women rather than on her own is Anthony. Arguably the most widely known suffragist of the past century,41 Anthony is commemorated in six monuments. Despite serving as the symbolic figurehead of the movement, she is most often depicted alongside other activists, a fitting tribute since Anthony herself championed the commissioning of multisubject monuments to honor suffrage activists. When Johnson approached Anthony about sculpting her marble portrait bust for the Women’s Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 (which served as the basis for the Portrait Monument in the Capitol), Anthony recommended that Johnson also sculpt a bust of Stanton, explaining: “I cannot think of having my bust go to the World Fair without Mrs. Stanton.”42 Anthony later suggested adding Mott to the grouping. Johnson’s sculpture established the convention of depicting Anthony with other activists, a form replicated in three separate New York monuments: When Anthony Met Stanton (1998; Seneca Falls), which depicts Anthony with Stanton and Amelia Bloomer; Let’s Have Tea (2001; Rochester), which pairs Anthony with Frederick Douglass; and the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument (2020; New York City), which portrays Anthony alongside Stanton and Truth.

The multisubject approach, however, is not without pitfalls and may also contribute to a reductionist understanding of the movement’s history. Anthony’s monuments, in particular, are important case studies for understanding the thorny ways in which racism is elided in favor of commemorative legibility. Let’s Have Tea (fig. 11) depicts the friendship between Anthony and Douglass. The monument was commissioned by the Susan B. Anthony Neighborhood Association, which aimed to elicit neighborhood pride by highlighting its illustrious history. Founded in the 1970s, the Association sought to revitalize a historical neighborhood that was primarily composed of middle- and working-class residents until the urban flight of the 1960s led to an increased number of vacant houses and, subsequently, crime.43 By creating a permanent statue to Anthony, the Association hoped to draw attention to her affiliation with Rochester’s other famous resident, Douglass.

Supported by a fundraising drive, the Association approached Laotian-born, Rochester-based artist Pepsy Kettavong (b. 1972) to create a sculpture for the neighborhood’s park, Susan B. Anthony Square. Kettavong’s finished bronze statue depicts Anthony and Douglass sitting in chairs face to face. A table between them holds a teapot, two cups, and two books—a volume of poetry and a book of law. The over-life-size figures appear like friends captured mid-conversation, as Anthony gestures to Douglass with a finger and Douglass opens his mouth to speak with one hand gently raised. Of the monument’s subjects, Kettavong remarked, “A black man and a white woman are drinking tea together, a Laotian makes their sculpture. It could be a metaphor for American democracy.”44

In presenting the mien of a friendly Anthony and Douglass, the statue does not acknowledge their at times contentious relationship and the racism that underlaid the suffrage movement. Douglass is largely remembered for his work as an abolitionist, but, like many abolitionists, he was also dedicated to achieving women’s suffrage.45 Going back to the antebellum era, activists in both movements were alternately collaborative and antagonistic. White women played a role in the fight for emancipation and enfranchisement for Black Americans, and many white female abolitionists, disillusioned by poor treatment from their white male counterparts, found their way to women’s rights. As outlined previously, bitter debates over who should be accorded the vote in the postbellum period leading up to the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment pitted abolitionists like Douglass, who afforded Black male suffrage precedence, against white suffragists who lobbied for universal suffrage. Anthony and Stanton specifically employed racist arguments to rally against the Black vote, arguing that “unwashed” and “uneducated” Black men were less deserving of the vote than white women.46 Despite such vocal racist positions, Douglass continued to lobby for women’s suffrage after the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. The debate, which conflated women with whiteness and Blackness with men, cast Black women’s interests to the “rhetorical margins.”47

A nearly identical set of issues was raised during the commissioning process of the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument (fig. 12; 2020). Located in New York City’s Central Park (only a few miles away from Saar’s Swing Low), the statue was to be the first monument in the park dedicated to a real, rather than allegorical, woman. The private organization spearheading the commission originally conceived the project as the Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Woman Suffrage Monument, positing Anthony and Stanton’s close friendship and decades-long collaboration as a leading force in the movement.48 The commission was awarded to Meredith Bergmann (b. 1955), whose proposed design paired the bronze figures of Anthony and Stanton raised on a plinth. Anthony was to stand behind a seated Stanton, who would be shown writing on a long scroll that cascaded down into a bronze ballot box. Included on the scroll would be quotations from twenty-two other women, including Truth, who were involved in the struggle for women’s suffrage. The quotations would fulfill the commission’s request for proposals, which specified that the artwork should “honor the memory of others besides Stanton and Anthony, who helped advance the cause of Woman Suffrage.”49

However, when the proposed design was publicly unveiled, it received a wave of criticism in the press for failing to include a Black suffragist. Critics, including Gloria Steinem, charged that by not including a Black activist, the monument whitewashed suffrage history.50 Bergmann ultimately amended the design and added the figure of Truth to the figural grouping of Anthony and Stanton. Yet the revision also received condemnation that echoed the issues raised by the reception of Let’s Have Tea. Critics contended that by portraying Truth in concert with Anthony and Stanton, the artist concealed the differences between white and Black suffrage activisms and glossed over Anthony and Stanton’s racism.51 Despite the embattled process of creation, the finished monument, which includes figures of Anthony, Stanton, and Truth, was dedicated on the centennial anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment in August 2020.52 In recognition of the limitations of the monumental form in capturing the full expanse of the movement’s history, the monument’s signage and didactic texts acknowledge the public debate spurred by the monument, concluding, “The controversy over its design speaks to the limitations of traditional figurative monuments to be inclusive, to fully represent something much larger than the persons depicted—in this case, a decades-long struggle that involved numerous contributors and aimed to benefit over half the population.”53

The process of memorializing a moment, movement, or individual is an abrogation of a complex history in service to symbolic storytelling. The conceit of a monument dedicated to a historical figure or group of figures distills the life of a subject into one static moment, freezing them in time. This is true of all monuments, but its effect is especially deleterious to popular understandings of suffrage history. Attending to the racial demographics at play in suffrage monumentation attests to the massive gap between the contributions made to suffrage by women of color and their continued lack of acknowledgment in memorials.

From Heretics to Heroes: How Monuments Ushered Suffrage into the American Canon

Swing Low, Let’s Have Tea, and the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument were erected during a flurry of monument-building during the first two decades of the twenty-first century, amid increasing efforts to break the “bronze ceiling” of male-dominated public monuments. The questions of when suffrage monuments were built and amid which context they emerged must be viewed within the gendered history of commemoration more broadly and within the chronology of suffrage monuments more specifically. Monuments dedicated to suffrage span 125 years and encompass over a century of social, economic, and political achievements for women in the United States (fig. 13). The first such monuments emerged at the end of the nineteenth century from the margins of political influence, were championed largely by local women’s groups, and often met strong opposition. By the centennial celebrations of 2020, the cause was safely historicized, honed to a familiar narrative, and far enough away from controversy that its activists were honored even by a conservative US president, who championed new monuments for reasons more partisan than celebratory. Looking at the timeline of monument-building reveals the ways in which the suffrage movement, once perceived as a radical disruption of the political order, became canonized within public spaces.

Fig. 13. Time series of suffrage monuments in the United States

ArcGIS map

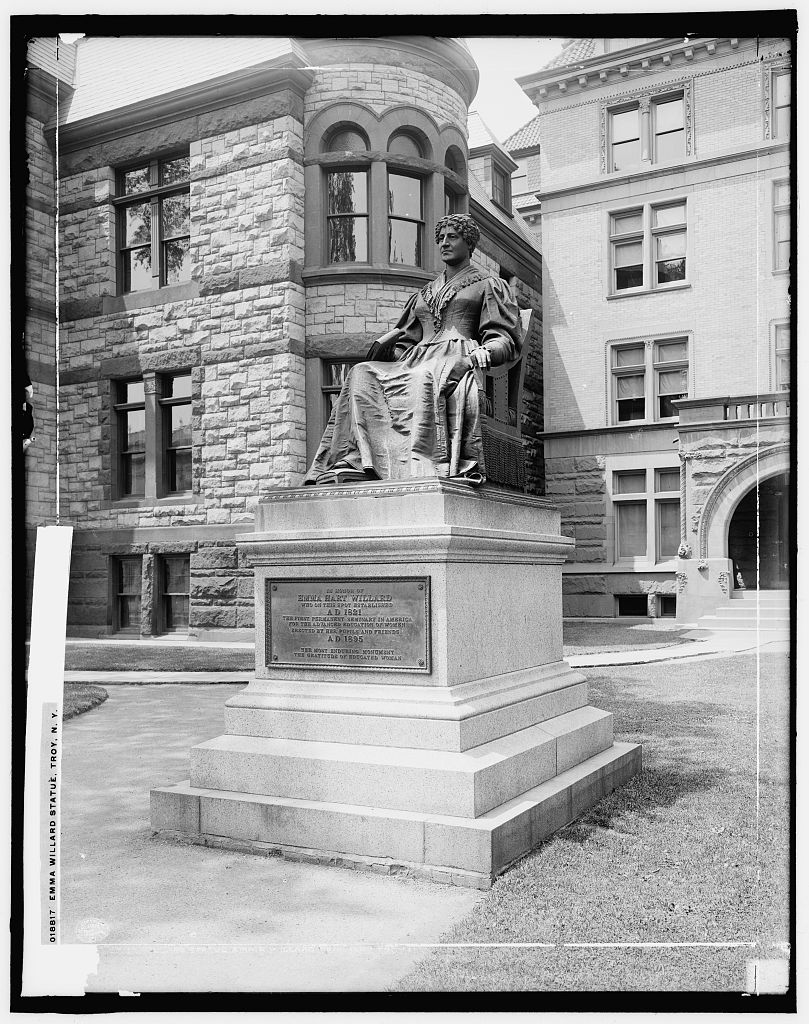

The first monument to a woman’s rights activist was built in Troy, New York, in 1895, twenty-five years before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment (fig. 14). The subject, Emma Willard (1787–1870), presents a dilemma in how to define the parameters of women’s suffrage and, subsequently, how to define a suffrage monument. Historically, when women appeared in public monuments, they were anonymous, allegorical figures, representing abstract ideals such as peace, loyalty, or vice. Suffragists were among the very first real women to be honored with public monuments, and their commemoration offered a rejoinder to the gendered language usually employed to describe allegorical sculptures. In 1821, Willard, recognized for her efforts to expand women’s access to education, founded the Troy Female Seminary, which is regarded as the first institution of higher learning for women in the United States. The school was renamed the Emma Willard School in 1895, the same year the statue of her was dedicated on the school grounds, serving as a second layer of commemoration.54 The Emma Willard Statue Association—composed of school alumnae—spearheaded the commission. In an 1890 New York Times article soliciting funds for the monument, the Association explained: “It seems appropriate . . . that the first statue erected in America in recognition of a woman’s notable work in the interest of the education of her sex should be in her honor.”55 Alexander Doyle (1857–1922), sculptor of Union and Confederate Civil War monuments,56 created the bronze statue, which depicts Willard seated. The position deliberately recalls Willard’s Victorian view on female oratory, that a woman could make a public speech only if she were seated, for then the speech becomes mere conversation. A photograph of the statue’s unveiling (fig. 15) shows a sea of alumnae and friends of the seminary; the predominantly female crowd visualizes the reach of Willard’s influence and the collective female support behind the monument’s creation.

At a time when women’s education was generally limited to finishing schools, the Troy Female Seminary provided women with educational opportunities equal to those offered to men. Willard educated a generation of “new women,” including many future suffrage leaders. Despite her influence on the movement, Willard did not publicly support women’s suffrage—even when beseeched by her former student Stanton. Instead, she placed women’s education above the right to vote.57 The seventy-four years between the founding of Willard’s school (1821) and the dedication of her monument (1895), however, witnessed radical progress in women’s education and suffrage, creating an ideal environment for a commemoration of Willard that would twin the causes and link her, at least tangentially, to the suffrage movement.

Women’s groups did not erect monuments to living leaders, as is typical of monument-building. Instead, they commemorated figures, like Willard, only after death. Prior to 1920, only five monuments dedicated to women’s rights activists had been erected, and these represent just three subjects: Willard, who was also honored at the Hall of Fame for Great Americans in New York City in 1905; Frances E. Willard (Emma Willard’s cousin), a temperance leader and suffragist, who was commemorated in National Statuary Hall in the US Capitol in 1905 and in the Hall of Fame for Great Americans in 1910; and Laura Smith Haviland (1808–1898), an abolitionist and suffragist, who was honored in 1909 with a statue in Adrian, Michigan. The Emma Willard School statue and the Haviland statue were intended to stand alone, while the others were created as part of broader statuary collections, thus inserting women into already existing sites specifically designated for public monuments. That the monument to Willard was built on the grounds of her namesake private school also suggests that public spaces were not yet open to commemorations of progressive women activists, which were still considered too radical in 1895. The paltry number of monuments to women activists erected before 1920 also demonstrates that, although suffragists were exerting political influence at the turn of the century, erecting monuments in public spaces was a herculean task that necessitated concerted, long-term organizing of public, monetary, and political support.

Few monuments were built immediately following the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, a fact that points to the struggles involved in leading the movement and the lack of support for its commemoration. Instead of a flurry of monument-building to commemorate the franchise, as one might expect, a fallow period followed. Only thirteen suffrage monuments were built between 1920 and 1990 (see fig. 13), including the Iowa Suffrage Monument (1936; Des Moines, Iowa) by Nellie Verne Walker (1874–1973); Esther Hobart Morris (1963; Cheyenne, Wyoming), sculpted by Avard Fairbanks (1897–1987); and Jeanette Rankin (1980; Helena, Montana), created by Terry Mimnaugh (b. 1955).

It was not until 1992 that monument-building to women increased at a rapid pace (see fig. 3). In fact, more monuments to women have been built since 1990—fifty-four—than in all the preceding years. Female commemoration is therefore a phenomenon almost entirely confined to the past thirty years. This corresponds to a boom in monument-building more generally, or what the art historian Erika Doss has called “memorial mania.”58 Historical circumstances also aligned to make women’s commemoration more publicly acceptable. The woman’s liberation movement of the 1970s led to the establishment of women’s history as a recognized field of study. The nonprofit National Women’s History Project (NWHP), established in 1980 by a collective of historians, sought to celebrate the achievements of women by providing educational and informational services to the public.59 Their first act was to coordinate the passage of a congressional resolution designating a National Women’s History Week to be held in March each year. Upon its official adoption in 1980, President Jimmy Carter proclaimed: “Too often the women were unsung, and sometimes their contributions went unnoticed. But the achievements, leadership, courage, strength and love of the women who built America was as vital as that of the men whose names we know so well. . . . I urge libraries, schools, and community organizations to focus their observances on the leaders who struggled for equality—Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth, Lucy Stone, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Harriet Tubman, and Alice Paul.”60 All the names referenced by Carter are women who participated in the suffrage movement, indicating the outsized role the movement played in popular understandings of women’s history. Women’s History Week was eventually extended to the entire month of March in 1990, and the women cited in Carter’s speech became popular subjects for monument builders in the proceeding years. The initiative and others like it helped to legitimize and popularize the scope of women’s history, and specifically suffrage history, during the final decades of the twentieth century.61

The year 1990 marked the seventieth anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, and to celebrate, a coalition of women’s groups, led by the NWP, ignited a public campaign to move Johnson’s Portrait Monument out of the Crypt to its original and more prestigious spot in the Rotunda. The restoration of the statue was cast as a feminist act imperative to the redistribution of the spaces of the Capitol in favor of gender parity. As Caroline Sparks, chair of the coalition, succinctly put it: “It’s not nice to put your forefathers in the living room and your foremothers in the basement.”62 The coalition soon learned that the road to the Rotunda was not an easy one, as it encountered a resistant Congress and an endless barrage of bureaucratic roadblocks.63 It was not until seven years later, on June 26, 1997, that the Portrait Monument was successfully re-sited. Hundreds of supporters gathered to witness its rededication in the Rotunda.64

The 1990s also saw a gradual but steady increase of women in leadership and elected offices. This culminated in 1992, the so-called Year of the Woman, when the number of women in the US Senate doubled and the number in Congress increased from twenty-eight to forty-seven.65 Monument-building is a slow process; many years tend to elapse from a monument being conceived to its being commissioned and finally dedicated, making it difficult to precisely identify underlying causes of monumental trends. However, it is striking that, since 1992, a new suffrage monument has been erected almost every year (and in some years multiple monuments).

The 2020 centennial anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment prompted a spate of commemorative events, including the erection of five new public monuments honoring the suffrage movement and its activists, with several more in progress as of this writing. This was presaged by the #MeToo movement and the 2017 Women’s March; both events galvanized conversations about women’s representation, just as planning for centennial celebrations began. Erecting suffrage monuments offered the country the opportunity both to reflect upon past injustices perpetrated against women and to recognize ongoing discrimination as a slate of new injustices was coming to light.66

National centennial celebrations culminated in a bipartisan bill approving the creation of a suffrage monument in Washington, DC, officially signaling the movement’s consecration in the canon of US history. The bill specifically recognizes the nonprofit organization Every Word We Utter as the commissioning body. Established in 2019, Every Word We Utter has one mission: to support Jane DeDecker’s efforts to design and create a tribute to the women’s suffrage movement and ensure its placement in Washington, DC. A sculptor in bronze, DeDecker, who is based in Loveland, Colorado, has created several suffrage monuments, including four casts of a statue of Harriet Tubman and three multisubject monuments that are currently in progress. DeDecker came up with the idea for the suffrage monument when she was a finalist for the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument commission in New York City. When Bergmann won that commission, DeDecker brought her design to the Colorado congressional delegation to be considered for this new project.67

In keeping with the conventions of the multisubject monument, Every Word We Utter: National Women’s Suffrage Monument (fig. 16)—which will ultimately be twenty feet tall—features a roster of suffragists: Anthony, Stanton, Truth, Harriet Stanton Blatch, Wells, and Paul. The title refers to Stanton’s reflection on the life of her compatriot Mott: “Every word we utter, every act we perform are wafted into innumerable other circles.”68 Although the monument currently only exists in maquette, DeDecker’s design portrays a three-dimensional narrative of the Nineteenth Amendment, with figures positioned at increasing heights, much like Johnson’s Portrait Monument. Anthony and Stanton serve as the base, representing the “beginning” of the suffrage movement; Truth and Blatch stand to their sides. Above them, Wells and Paul form the next generation of the movement, symbolically and literally standing on their shoulders. Paul holds the ratification flag, which cascades down the side of the monument and is encircled with signatures of women involved in the fight for suffrage—echoing the Stanton quote.

In one of his final acts as president in 2020, Donald J. Trump signed H.R. 473 into law, officially authorizing the creation of DeDecker’s monument. The final design and site will still require approval by the National Capital Memorial Advisory Commission. On its face, this could be read as a narrative of victory: in 1921, Johnson’s Portrait Monument suffered the indignity of a brief installment in the Capitol Rotunda followed by a swift removal to the basement. One hundred years later, a sitting president proudly authorized the first outdoor suffrage monument in the nation’s capital.

The bipartisan support for DeDecker’s new monument—during a period of rampant and virulent political discord—indicates that the suffrage movement, which in its time was among the most extremist political efforts in US history, had become thoroughly integrated in public history and largely uncontroversial. Anthony was a provocative and at times deeply unpopular figure during her lifetime. She was mocked by the public and the press—a reporter once called her a “hobgoblin of the public mind”69—and her rhetoric faced bitter opposition from both sides of the political spectrum. Paul, who serves at the apex of the monument, was violently arrested in 1917 for picketing in front of the White House in an attempt to pressure President Woodrow Wilson into supporting the Nineteenth Amendment. While in jail, she, along with 150 other women, went on hunger strikes and were subsequently force-fed through tubes.70 Wells, in particular, exemplifies the ways in which Black women suffragists were perceived as especially “dangerous,” fighting racialized and gendered injustices on multiple fronts. When Wells, who founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago, was told she and other women of color would have to march at the back of the 1913 Suffrage Parade in Washington, DC, she stood on the parade sidelines until the Chicago contingent of white women passed and then defiantly joined the march. For her tireless work on antilynching campaigns, she was frequently the target of public opprobrium, violent threats, and attacks.71 The fact that suffrage, by 2020, had shed its political progressivism is amplified by the larger dialogue surrounding public monuments.

In the summer of 2020, protestors around the world began defacing, beheading, and toppling monuments with racist and colonialist histories, including those honoring Confederate generals and Christopher Columbus.72 These actions were spurred by the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests against police brutality and specifically the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by a Minneapolis police officer. The public monument, as a commemorative category, quickly became a vector for reckoning with a racist past and present. In response to the so-called attack on public monuments and politicized readings of US history, Trump established an executive order calling for the establishment of a “Garden of American Heroes,”73 a landscape of 244 statues of significant US historical figures, which included eleven suffragists.74 Trump’s support for DeDecker’s Every Word We Utter came at the same time, indicating that he saw the suffrage monument, at least in part, as a rebuke to the contemporary social protests. That Trump—who has been accused by twenty-six women of sexual misconduct75—was the president who authorized the first suffrage monument to be erected on public ground in the nation’s capital, at the site where Paul and Wells once held their protests, is further evidence of how thoroughly deradicalized the suffrage movement has become.

Looking at the chronology of suffrage monument-building, we see the full arc of public perception of the movement mapped onto the shifting social and political contexts of the United States. What began as largely unrecognized in the commemorative landscape—and, in the instance of Johnson’s Portrait Monument, deliberately sidelined—grew quickly in the wake of the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s. The organized efforts to integrate women’s history into the larger story of US history greatly accelerated monument-building throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, and by 2020 the movement had become thoroughly canonized, brought up from America’s metaphoric basement and into the spotlight. Commemorations of suffrage during its centennial year allowed the US public to examine issues of sexism through the lens of a rearview mirror. Yet the social cataclysms of the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, and the conservative backlash they prompted, expose the dangers inherent in celebrating an image of equality while decoupling the radical and progressive efforts it took to get there.

The Regionality of Suffrage Memory: Mapping the Concentration of Commemorative Sites across the United States

Every Word We Utter illustrates how a monument’s location can amplify its significance and complicate its symbolic meaning. A place in the nation’s capital among its illustrious collection of national monuments suggests that the suffrage movement is indeed understood as one with national relevance. The location conveys the existential impact of the Nineteenth Amendment on American identity. This is true far beyond the capital, however, as the movement and its history are intimately connected to regionality. Regional distinctions emerged within the movement from its earliest days and are reflected in the locations of its commemorations. The contours of suffrage memory and the contest over its geographic legacies are readily visible when surveying the nationwide distribution of suffrage monuments. In the aggregate map (fig. 17), distinct regional concentrations of monuments become apparent. The Northeast holds the greatest number of monuments, with forty-four; upstate New York alone has ten. In contrast, the South has twelve monuments, the West Coast has four suffrage monuments (all in California), and the entire region of the Northwest and Western Plains has only five monuments. Concentrating on the disparities in the number of monuments between Northeast and West, this section argues that the regional distribution of monuments reifies the narrative that the movement began and was predominantly based in the Northeast, though a closer look at the landscape also reveals the ways in which Western states have sought to emphasize their role in the movement’s history.

The density of monuments within the Northeast generally, and upstate New York specifically, animates the foundational myth of Seneca Falls as the so-called birthplace of women’s rights. This reputation was born of decades of concerted efforts by women’s groups to position the town as the movement’s epicenter, shifting the historical record from the West—where US women first gained the vote—to the Northeast. Seneca Falls was actively constructed as a site of suffrage pilgrimage, starting with the first official commemoration of the convention in 1908, on its sixtieth anniversary. Other public observations followed, including the seventy-fifth anniversary celebration in 1923 and the centennial anniversary celebrations in 1948.76 In 1979, a group of local feminists and historians organized to save Stanton’s house, which had been designated a National Historic Landmark in 1965 but was being threatened by commercial developers. At the time, there was little in Seneca Falls that suggested its significant role in US history. Once a robust manufacturing center, Seneca Falls, like Rochester and many postindustrial American towns, faced an ominous future by the 1970s.77 The town’s historic sites, including those associated with the nineteenth-century women’s rights movement, were badly dilapidated or repurposed as commercial spaces.

Fig. 18. Women’s Rights National Historic Park sites, Seneca Falls, NY

ArcGIS map

In 1980, working under the auspices of the Elizabeth Cady Stanton Foundation (ECSF), the women envisioned a new national park dedicated to preserving the nineteenth-century history of women’s rights, which would include the Stanton House and three other discontiguous sites in the area (fig. 18).78 They joined forces with the Seneca Falls Chamber of Commerce to petition the National Parks Service (NPS) for national park status.79 According to Nancy Dubner, an early member of the Foundation, the village was not initially keen on drawing attention to its history as a center of feminist activism.80 Support only began to grow when it became clear that the town’s feminist history could be translated into tourism and profit. Richard Campo, director of County Commerce, put it most clearly when he said, “We have a gimmick here that we should milk for all it’s worth.”81 Local business owners found themselves in an unlikely alliance with feminists, all of whom successfully lobbied for the creation of a national park. In one of his last acts before leaving office, President Carter authorized the creation of the Women’s Rights National Historic Park (WRNHP), the first national park specifically dedicated to the women’s movement.82

WRNHP includes two suffrage monuments that honor East Coast activists and one more that is in progress: The First Wave Statue (1992) by Lloyd Lillie (1933–2020), When Anthony Met Stanton (1998) by Ted Aub (b. 1955), and Ripples of Change by DeDecker (in progress). The first in the suite of bronze multisubject monuments, Lillie’s The First Wave Statue (fig. 19) is also the largest. The sculpture honors the 1848 convention attendees in bronze. Life-size sculptures depict twenty men and women—including key figures such as Stanton and Douglass, as well as anonymous participants—in clusters, as if they are emerging from the convention.83 Lillie positioned the figures, set directly on the ground, in casual, uneven groupings. The sculptural arrangements allow visitors to walk between figures—as Lillie explained, “like it’s a maze”—and imagine themselves participating in the historical event.84 Taken together, the figures visualize the history of the site and convey the importance of the convention, while simultaneously working to humanize participants by placing them on the same level as viewers.85 The monument is sited in the visitor’s center, the de facto epicenter of the park, complementing the NPS exhibits and educational resources.

The important role that the NPS plays in the creation of monuments is apparent when we lay the NPS map of historically significant sites relevant to the suffrage movement (sites listed on the National Register of Historic Sites and other historic homes, museums, and markers) onto the map of suffrage monuments (fig. 20). Clear links emerge between historic events, places, and public commemorations. The concentration of historic places related to suffrage in the Northeast (particularly New York City and Rochester) and the Midwest (Chicago) corresponds to the high number of monuments in those areas. In contrast, the region of the Northwest and Western Plains has fewer historic suffrage sites and only a handful of monuments. The correlation—positive in the case of the Northeast, negative in the case of the West—between the concentration of historic sites in a given region and its number of public monuments confirms that established public history networks and organizations are vital to the process of erecting monuments. In other words, areas with more historic sites and more monuments clearly have better infrastructure and support for public commemoration.

Fig. 20. Suffrage monuments and point layer representing places that were pertinent to the suffrage movement. Historic places include those listed on the National Register of Historic Sites and other historic homes, museums, markers, and plaques

ArcGIS map

Colorado, Utah, and Idaho were among the first to grant female citizens the right to vote. The territory of Wyoming led the way in 1869 and passed laws giving married women control of their property and mandating equal pay for female teachers. Despite this history, why, then, are there only five monuments in the region rather than dozens?

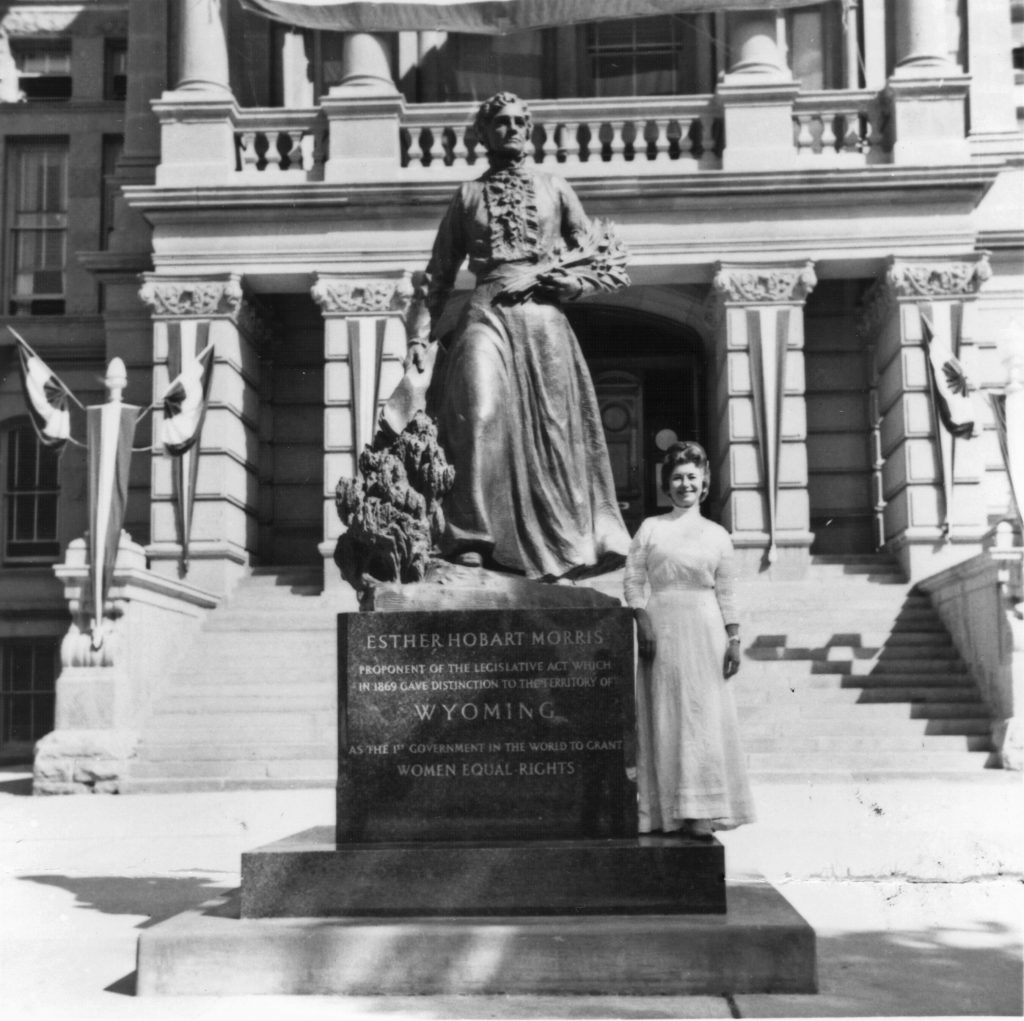

A statue of Esther Hobart Morris (1814–1902) was one of the first suffrage monuments in the region, erected in Cheyenne, Wyoming, in 1963. Her monument demonstrates how, starting in the 1960s, Western states sought to bolster their reputation in suffrage history and challenge New York’s dominance.

In 1960, Wyoming commissioned a bronze statue of Morris for the National Statuary Hall (NSH) in the US Capitol, and a replica for the State Capitol three years later for the seventy-fifth anniversary of the state granting women the right to vote (fig. 21). Morris was a champion of women’s voting rights; she also served as the territory’s first female justice of the peace and was the first woman to hold public office in a state government. A widely distributed 1920 pamphlet, How Woman Suffrage Came to Wyoming, authored by historian Grace Raymond Hebard, portrayed Morris as the single most important figure in the suffrage movement. However, by 1960 she was little known outside Wyoming.86 Edness K. Wilkins, the first female speaker of the Wyoming House of Representatives, and Nellie Tayloe Ross, the first woman in the United States to serve as a state governor, urged the Wyoming House of Representatives to put forth a bill for the erection of a statue to Morris. The bill was initially met with strong opposition from male senators, but when the women of Wyoming sent a flurry of telegrams in support of the statue, the senators relented and gave overwhelming approval to the measure.87

Overseen by the Wyoming State Historical Society, the Esther Hobart Morris Statue Commission selected University of Utah sculpture professor Avard Fairbanks to create the monument. Fairbanks, who was known for portraits of Lincoln, compared Morris to Moses, “who led a captive people to liberty,” and Hammurabi of Babylon, “who gave his codes of laws”—comparisons he visualized in his sculptural portrayal.88 Raised on a plinth, the nine-foot Morris strides forward, one foot stepping up onto a craggy ledge, her long dress billowing behind her. In one hand she holds a sheaf of papers, presumably legislative documents, and in the other, a bundle of flowers. The inscription on the base reads: “Esther Hobart Morris / proponent of the legislative act in 1869 which gave distinction to the territory of Wyoming as the 1st government in the world to grant women equal rights.” The dedication proclaims Wyoming’s leading role in the women’s rights movement, not just in the nation but in the world at large.

The 1960 statue was sent to the National Statuary Hall at the US Capitol in Washington, DC, whereas its 1963 copy was erected at the Wyoming State House in Cheyenne. This highlights one regional distinction between the Northeast and West that emerges from the dataset. In the East, commemorations appear more frequently in federally designated NPS sites; in the West, capitol buildings are preferred for historical monuments, especially those to suffrage. A capitol building offers an august venue for a public monument, imbuing it with political significance. National Statuary Hall extended that political significance further, providing Wyoming a platform to celebrate Morris on a national scale.

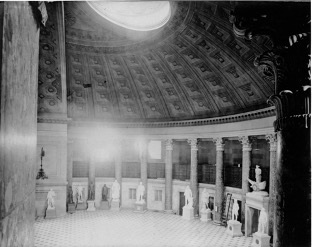

Established by President Abraham Lincoln in 1864, Statuary Hall (fig. 22) is a unique nexus of national and state-specific interests and, as such, is a valuable dataset unto itself, one that complicates the perceived dominance of the Northeast in suffrage commemorations. The hall offers each state the opportunity to submit two statues for permanent display. Of the nine statues of women currently in the hall, six of the women were suffragists, and all were honored by states outside of the Northeast: Morris and Keller (donated by Alabama), Jeanette Rankin (donated by Montana), Maria Sanford (donated by Minnesota), and Frances E. Willard (donated by Illinois).89

The patchy geographic distribution of suffrage commemoration across the United States makes it difficult to draw a comprehensive landscape of commemorative activities. Commemorations favor East Coast sites and neglect the many galvanizing contributions from activists west of the Mississippi.90 If we read these statues as a historical text, one attempting to tell the geographic story of the women’s movement, it fails. Such results speak to the enduring prevalence of the Seneca Falls–centric narrative advanced by Anthony and Stanton. In the end, mapping the landscape of suffrage commemoration tells us more about mythmaking and contemporary actors than it does about the actual historical contours of the nineteenth-century movement. However, looking more closely at National Statuary Hall reveals the ways that states outside the Northeast have highlighted their contributions in the movement’s history.

The Dilemma of Style: Beyond the Figuration/Abstraction Binary

The subjects and aesthetics of most monuments in this dataset, such as Fairbanks’s statue of Morris, lend a nineteenth-century air to their subjects, but it is crucial to recognize that they constitute a collection of largely contemporary art, as the timeline makes evident. By assembling the monument artists and cataloguing an overview of their visual vocabulary, this study offers an alternative view of the prevailing stylistic movements of art and artists in the United States during the same interval.

The dilemma of style has long plagued the study of public monuments. From the realist portraiture of the late nineteenth century and the stylized idealism of the early twentieth to the preference for minimalism in the late twentieth century, the favored style of monuments has evolved over the decades, as each era answered the question, What is the appropriate form of a monument? This question has taken on new urgency in recent years, as more diverse historical actors enter the monumental landscape. The central conflict is a simplistic binary that sets realism in opposition to abstraction. Many attendant valuations end up pinned to each side: populist versus elitist, academic versus avant-garde, conservative versus progressive, kitschy versus tasteful, low art versus high art.

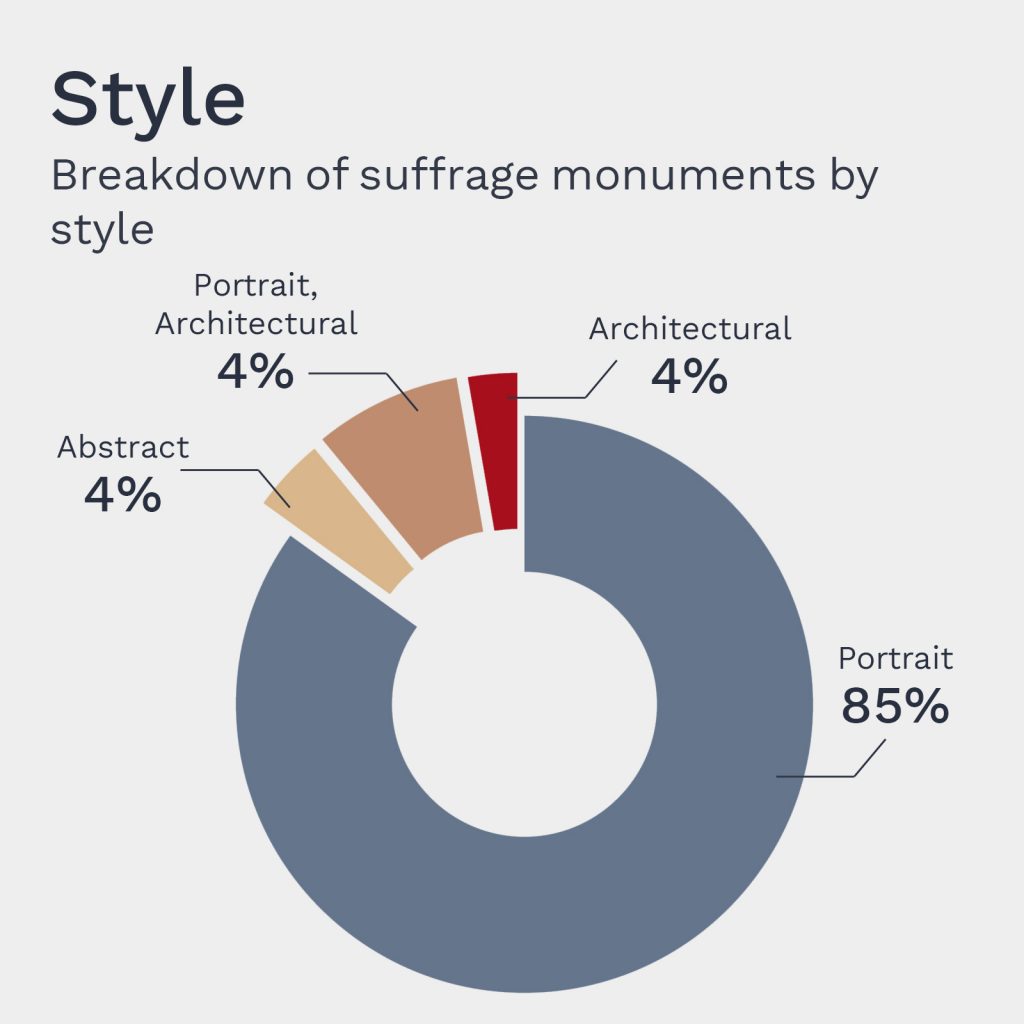

In suffrage commemoration, realism is the rule and other styles the exception. Eighty-six percent of all suffrage monuments are portrait sculptures that utilize realistic figuration to depict their subjects (fig. 23). There have been stylistic departures that expand upon the visual conventions of the traditional portrait monument. The majority, however, embrace representational visual language to convey monumentality and dignity—these are qualities typically associated with male subjects, yet they do not uniformly reinforce a masculine paradigm. Their very presence within this country’s corpus of monuments represents the achievements of women and challenges traditional conceptions of a heroic ideal.

One of the earliest monuments in this dataset is the marble portrait statue of Frances E. Willard (fig. 24) by Helen Farnsworth Mears (1872–1916), which was donated to the National Statuary Hall by the state of Illinois in 1905. The statue helped to establish two standards of suffrage monuments: its format (figurative, realistic, life-size or larger) and its artist (a woman). Willard, a prominent figure in the temperance movement, was the second president of the national Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Under her leadership, the WCTU expanded its focus to embrace women’s rights, including suffrage and women’s education. Fellow suffragist and WCTU member Anna Adams Gordon (1853–1931) was the dominant force behind the commission. After Willard’s death in 1898, Gordon doggedly lobbied the state to nominate Willard to the National Statuary Hall and provided funds for the creation of the statue. Serving as the chair of the Illinois Board of Commissioners for the Frances Willard statue, Gordon shepherded its creation and selected the artist.

Intent on commissioning a female artist, Gordon selected Mears, who had studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and had sculpted several other prominent public monuments. As a former studio assistant to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, she worked on the large equestrian statue of General Sherman, and her statue Genius of Wisconsin was selected to represent Illinois at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893.91 Gordon expressed a decided preference for a woman artist and wrote to several prominent women’s groups soliciting recommendations. In response, Anthony implored her, “I hope you will certainly give the job to a woman. I have never known a man artist, sculptor or painter to do other than give a masculine look when he tried to express strength of character in a woman’s face.”92

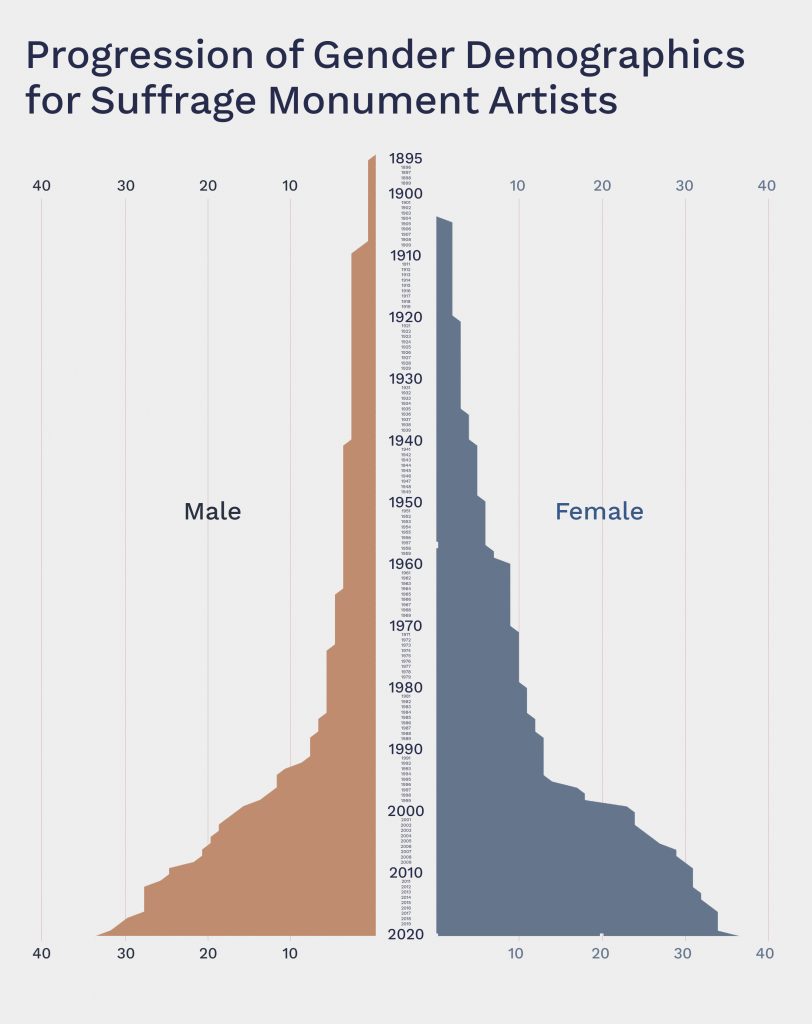

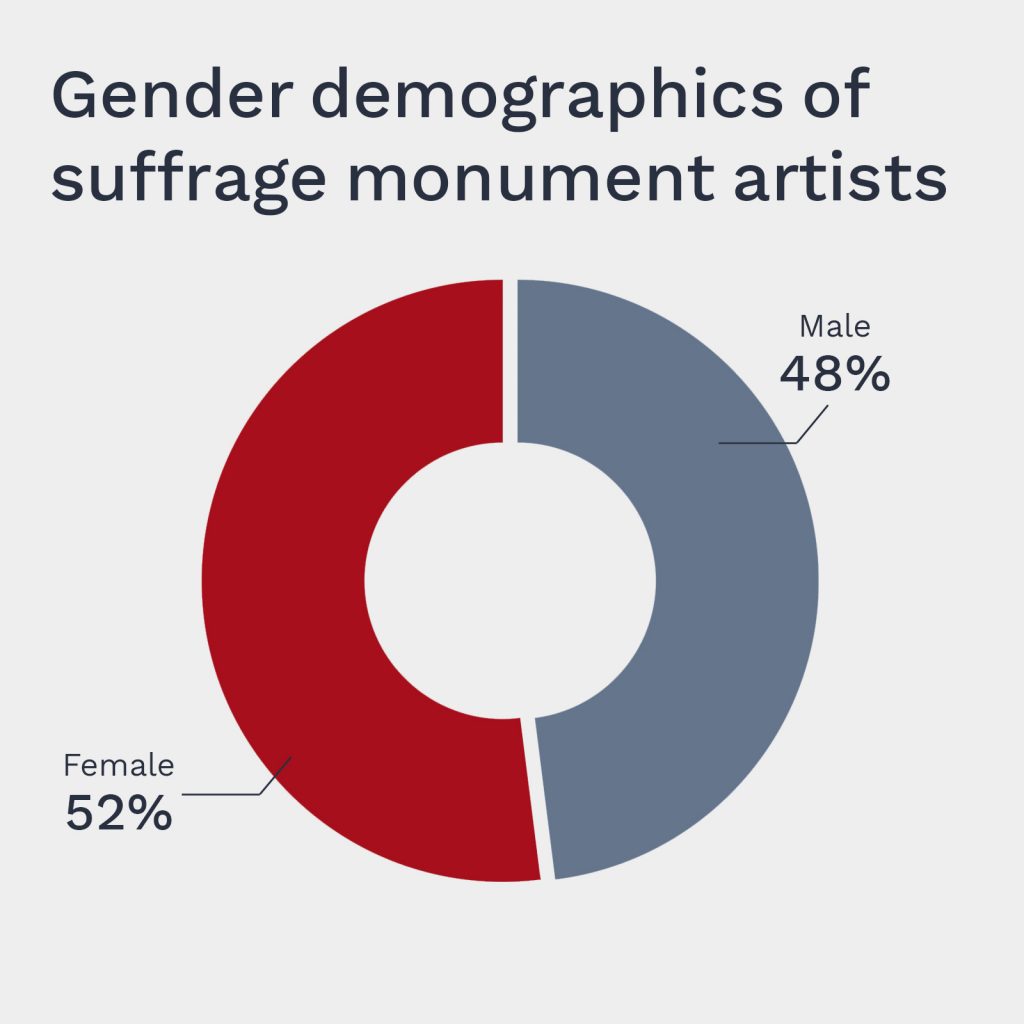

Anthony’s criticism of male artists explicated the difficulty of navigating the wholly new territory of commemorating women. For many women such as Anthony, allowing female artists to sculpt female subjects not only afforded professional opportunities but was paramount to rearticulating a heroic ideal that did not rely on traditional masculine styles of representation. Gordon’s and Anthony’s preference for female artists was realized in 1936, when the number of women monument artists in this dataset first exceeded that of men (fig. 25). Although not an overwhelming majority, the 52 percent of suffrage monuments by women (fig. 26) (current as of this writing) indicates that sponsors were attuned to how commemorations of women from the past could advance the professional profiles of women in the present.

Mears depicted Willard standing in front of a lectern—a significant departure from the statue of a seated Emma Willard commissioned only ten years prior. Raised on a plinth, Mears’s Willard stands erect, with one hand resting atop the stand and one hand holding papers by her side, a reference to her skills as an orator. In order to capture her exact likeness, Mears based the depiction on photographs of Willard, including an 1894 image of her speaking at St. Margaret’s Church in Horsmonden, England.93 Mears’s statue conforms to the stylistic conventions of a hero on a pedestal, yet its female subject is a subversion of its traditionally masculine conceptions of heroism.

The Illinois bill designating that Willard’s representation be sent to National Statuary Hall made note of fifteen eminent male citizens of the state, including Ulysses S. Grant and Abraham Lincoln, who lost out on commemoration in favor of Willard.94 In his dedication address, Representative Henry Thomas Rainey (D-IL) framed the decision in gendered terms: “Men acquired fame upon the battlefield, amid the pomp and glory of war. This opportunity is denied to women. Men acquire fame as diplomats and statesmen, but this opportunity is also closed to women; and so, we have in Statuary Hall figures of heroic size presented by the States; nearly all of them the portraits in stone and bronze of men who have had access to these great fields of human effort and human ambition; for them the door of opportunity always stood open.”95 He continued that after the Civil War the need to honor a different kind of hero emerged. “It was at this time that there came out of the North a new leader—not a leader of armed men, but a leader of unarmed women—a woman of supreme capacity, mental and moral and physical. . . . She led the fight for the home, for personal purity, for better habits of living, for the rights of children, for the uplifting of women.”96 Rainey’s rhetoric reflects the nineteenth-century ideology of “true womanhood,” which positioned women as the moral center of the nation.97 Illinois therefore placed Willard within the boundaries of early twentieth-century concepts of heroism, stressing her femininity while also casting her in the guise of a masculine leader.

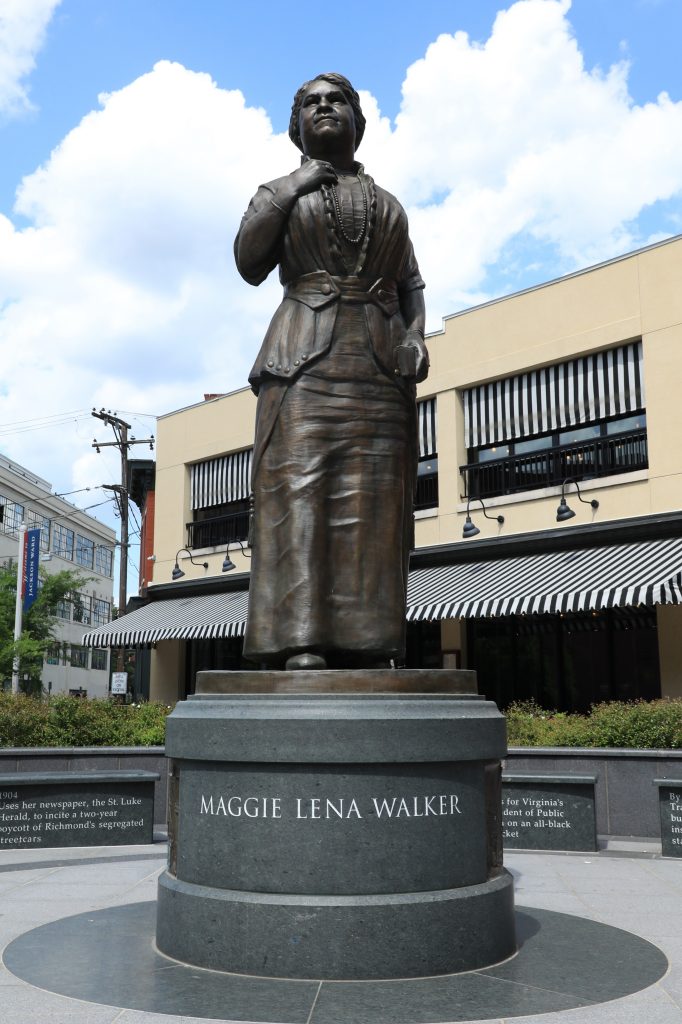

In returning to the question of style and format, the portrait statue as the dominant form endures, as seen in a contemporary monument honoring Maggie L. Walker (1864–1934) (fig. 27). Dedicated in 2017 at the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site in Richmond, Virginia, the ten-foot bronze statue, sculpted by Toby Mendez (b. 1963), depicts Walker standing on a plinth, a checkbook in hand to signify her legacy as the first Black woman to charter a bank. This iconographic detail operates to signal her profession, just as the lectern and papers represent Willard’s role as an orator. More than one hundred years separate the two statues, yet the formal vocabulary remains much the same. Willard and Walker are just two of the dozens of representational portrait statues honoring suffragists across the country.

In the 1990s, the conceptual and formal reimaging of monuments coincided with the increase of public commemoration of women, raising questions about whether portrait statues to women should be built at all. Feminist scholars writing about monuments to women argued that celebrating women through commemorative statuary merely reinforces a masculine framework.98 The 1980s and 1990s saw a paradigmatic shift in commemorative practices away from portraits in favor of new forms of monumentation, best exemplified by the minimalism of Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial (1982) and other contemporaneous “counter-monuments” favored in Holocaust commemorations. Such examples resist realistic figuration, overt didacticism, and overdetermined heroic rhetoric.99

The move to expand the monumental form beyond the “statue on a pedestal” remains limited. Communities have elected to build new realist monuments to previously marginalized subjects as explicit rejoinders to the white male–dominated landscape of public statuary. The divide between critical discourses of commemoration and the expectations of diverse publics came to a head over a planned monument commemorating abolitionists in Willoughby Square Park in Brooklyn in 2020. Artist Kameelah Janan Rasheed’s winning proposal sought to reinvent the vertical, representational format by installing engravings and bronze placards in the ground. Activists, who for twenty years had pushed the city to honor Brooklyn’s abolitionist roots, complained that Rasheed’s design was too abstract. They argued that women and people of color need to see themselves figuratively represented in public monuments. Shawné Lee, whose family helped ignite the neighborhood preservation effort, articulated this viewpoint: “I want to see historical figures represented, because these days we need to see people who look like us in the city’s monuments.”100 The populist argument made for portrait statuary and realist figuration is a persuasive one: such works employ a familiar visual language whose exalted symbolism is easily understood by audiences.