A Conversation on Critical Cataloging

PDF: Midavaine, Hooper, and Meyers, Conversation on Critical Cataloging

Critical cataloging can seem a solitary task, but the foundational work is most successful when it is collaborative. Reflecting on this are Sophia Meyers, Rosalie Hooper, and Bree Midavaine, who contributed to critical cataloging efforts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) through the Bias Remediation for Interpretation and Data (BRID) Team from April 2022 to January 2024. Here we discuss our experiences as members of the BRID team and our perspectives on the impact of this work. These views are the authors’ own and do not represent the official stance of the institution.

On Initial Steps for Collaborating on Critical Cataloging Efforts

Bree Midavaine (BM): As a librarian I have been involved in critical cataloging for much of my career. At the PMA, it dovetailed with my work on a Mellon Foundation grant project, the Art Information Commons,1 which was tasked with connecting information on Black artists from databases across the museum. I remember attending separate meetings with different curatorial departments regarding our standards for recording the nationality/ location of historical artists where the geopolitical boundaries of towns/ cities/ countries had changed over time. I realized each department was tackling the same question as their colleagues in other departments, but independently. While the team was formed largely in response to these siloed conversations, it was also spurred by larger trends in museums and cultural institutions. Part of the grant project involved meeting with external colleagues to discuss their processes. For example, due to the Library & Archives involvement on the Linked Art editorial board, we were aware of the development of Yale University’s linked-data cross-collection discovery platform LUX2 and the various committees that were developed by Yale in the process. As such, we met with colleagues at the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) to discuss their critical cataloging processes and working-group development as they collaborated with others in the institution on LUX.

The Library & Archives at this same time was implementing a new digital asset management system. As we investigated this system’s possible capabilities for presenting art objects on the museum’s website, we were intrigued by the Victoria and Albert Museum’s (V&A) “Collections” section of their website, which includes content warnings3 and image masking.4 We wanted to know more about their flagging process and what policies they had developed as they determined which objects received that treatment. This conversation with staff members at the V&A, as well as what we learned from YCBA critical-cataloging efforts, informed the development of the guide. It also became evident we needed to form a team with multiple perspectives.

Rosalie Hooper (RH): In my work in interpretation, the need for critical cataloging arose on a case-by-case basis as we encountered individual artworks featured in exhibitions that had associated data that staff wanted to reconsider, such as a descriptive artwork title created by earlier curators that contained an out-of-date word. After several similar situations, other colleagues and I felt we needed a more consistent approach to how we consider these questions and came together to develop procedures and documentation to reconsider our cataloging.

Sophia Meyers (SM): In my experience. a topic or theme of an exhibition brings to light needed cataloging updates. If a curator is adding new objects to the galleries or even addressing well-known objects through a new lens, this creates conversations about how an artwork is presented and what needs to change on the labels. For example, reconsidering artist versus maker versus designer in the Arts and Crafts movement necessitates the change of not only the work going on display but the related works in the collection. This clarification will make the exhibition labels more nuanced and thoughtful, but the first step is the database cataloging.

On the Bias Remediation for Interpretation and Data (BRID) Team and Guide

BM: In April 2022, Rosalie and I worked to assemble a team consisting of members from departments across the museum, including curators, curatorial assistants, editors, librarians, fellows, and educational staff (figs. 1–3). Working collaboratively over the next year, we developed a Bias Remediation for Interpretation and Data Guide, containing a set of questions and recommendations staff can consider for flagging, remediating, and documenting decisions taken to address concerns of implicit and explicit bias within our collections data. This work culminated in September 2023 with the completion of a first draft of the guide, which was presented at a symposium5 sponsored by the Library & Archives Art Information Commons initiative. This symposium gathered speakers from across the world to discuss critical cataloging efforts in their institutions.

RH: Collaboration has been essential to the success of this work. We remain very grateful to staff at the V&A, the Getty, Princeton, and Yale, who graciously shared their processes with us as we began to consider what a holistic approach to critical cataloging might look like at the PMA. The development of the BRID guide was an effort to make this work more institutionally driven than individually so. Previously, decisions about when and how to engage in critical cataloging were often driven by individual experiences and preferences. With BRID, we aimed to create a shared set of expectations about when and how this work happens.

On the Challenges of Critical Cataloging

RH: The long-term work of improving cataloging involves careful consideration and research, and though it has a big impact, it is often easy to prioritize other, more immediately pressing tasks and projects. In my role, I see the ripple effects of investment in this work, as reconsiderations of how we describe artworks change how we think about broader art-historical concepts. For example, a decision to credit many examples of early American decorative arts as made in the “Shop of . . .” allows us to better recognize and remember the many hands that contributed to artworks beyond the singular name of a shop owner. There has always been a degree of interpretation at play in cataloging, in terms of what information is included and omitted: who is represented, how artworks are described, which political boundaries we recognize, and other choices. It is exciting at this moment to see a growing sense of awareness, criticality, and responsibility about how our individual choices shape our larger understandings of artworks and museums.

SM: While being collaborative work, critical cataloging is also uniquely individual to each department and object. Although some terms can be batch-updated in a database, the reality is that careful cataloging requires object-by-object attention. For the American Art department, standard practice dictates that all objects start with the geography field listed as the United States, but does that make sense for objects dated before the creation of the United States? If not, each object pre-1783 needs to be reviewed. I believe having designated time to do the work is the major hurdle to getting updated cataloging done.

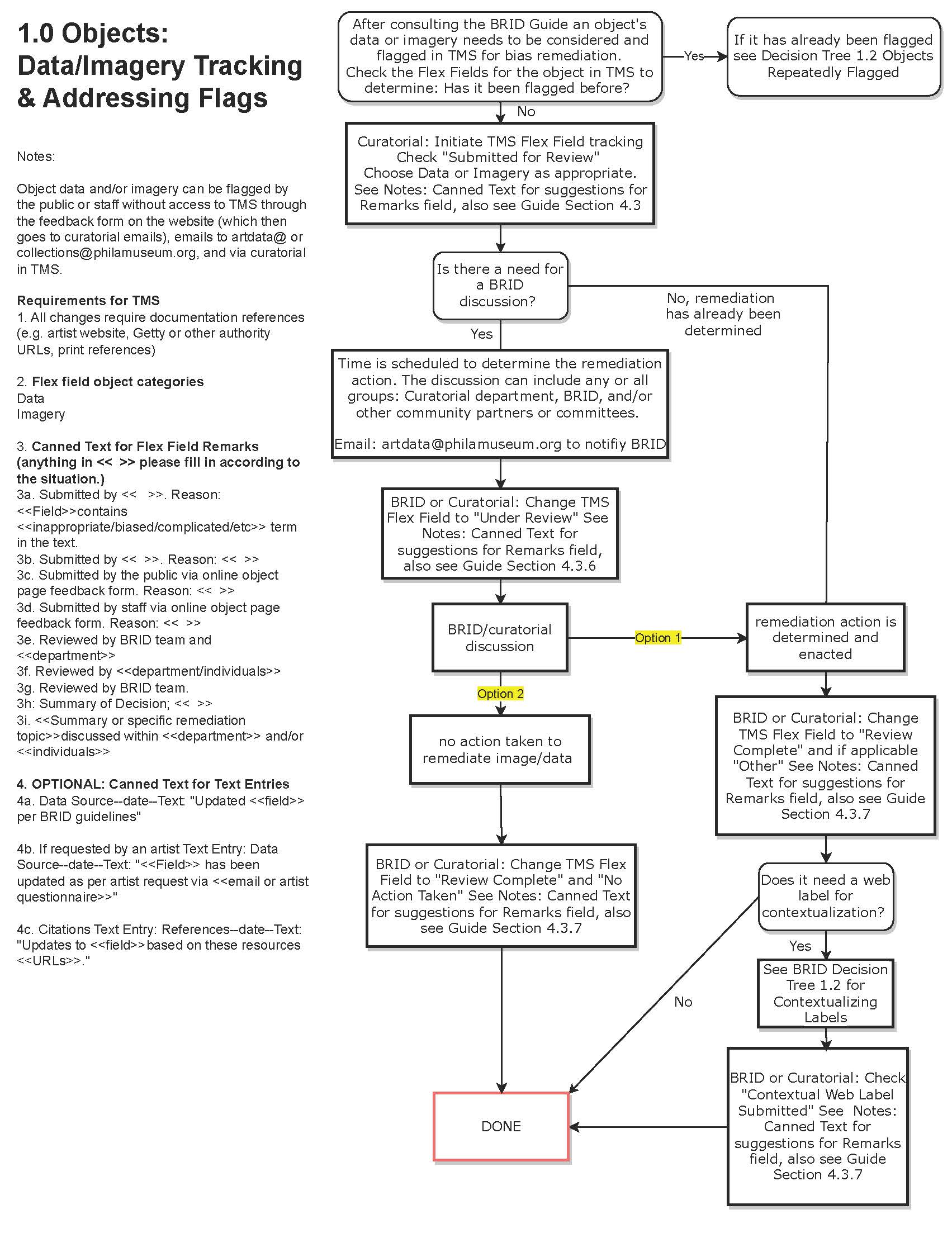

BM: Finding time can be tricky, as well as maintaining the momentum. I look at the guide as the first step; the next step is to integrate it naturally into our daily work. It was not developed in response to a specific task or project; rather we worked in the theoretical. It was a vision of how we hoped the practice of critical cataloging could work, as seen in figure 4. We are grateful to have the broad vision of the guide. It is nimble and provides flexibility in its recommendations that we can work from as we adapt it to the realities and practicalities of critical cataloging work. One way is by incorporating the BRID guide into our existing documentation for entering objects into our collection database.

On the Long-Term Work and Impact of Critical Cataloging

SM: I see the long-term impact of my work as part of a larger history of the objects and institution. I want to make sure cataloging decisions make sense in this time and in future times to a variety of audiences. It is important that my work has that type of longevity. Incorporating aspects of the guide in our daily work is a way to ensure it outlasts a single individual.

BM: Critical cataloging can broadly affect research and collection development. The “Mrs. Project” was a large archival remediation project aimed at recording a woman’s given name for those formerly known only as Mrs. [husband’s name] in our database. They are now findable and can be connected to other resources. As we assess our library collections, this work allows us to see gaps in our collecting and amend what is collected, which in turn gives additional resources to our staff for research and exhibition planning. Critical cataloging gives representation to formerly marginalized groups and in turn improves access so new knowledge can be created. It reminds us that the data we work with is not static, sitting in a database. It is information giving context to archival material, objects, and artists; it may determine whose stories are told and how; it can inform what is preserved and how objects are labeled; and it is useful for researchers. Critical cataloging practices have the power to transform exhibitions, shape collection development (for not just libraries and archives but acquisitions as well), build connections to our communities, and create new understandings about art, artists, and history.

RH: The categories we use in databases to describe and classify artworks are foundational to how we perceive these artworks. By reconsidering the language and methodologies we use to catalog, we then shift our understanding of the artworks, expanding the ways we interpret and create new points of connection with audiences. Recognizing the many hands who contribute to the creation of an object, or the complicated geopolitical histories impacting how we attribute nationality, or the changing meanings of words in a descriptive title opens new ways of engaging with the public and changes what we see as the impacts of our work.

Cite this article: Bree Midavaine, Rosalie Hooper, and Sophia Meyers, “A Conversation on Critical Cataloging,” in “Critical Cataloging: Researching American Art History on Its Own Terms,” ed. Tracy Stuber and Jennifer Way, Digital Dialogues, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 11, no. 1 (Spring 2025), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19942.

Notes

- “Art Information Commons,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Library & Archives, accessed April 6, 2025, https://artinformationcommons.github.io. ↵

- “LUX: Yale Collections Discovery,” Yale University, accessed April 6, 2025, https://lux.collections.yale.edu. ↵

- Sample of a Victoria and Albert Museum artwork page with a content warning. “Little Alabama Coon,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed April 6, 2025, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1292326/little-alabama-coon-sheet-music-starr-hattie. ↵

- Sample of a Victoria and Albert Museum artwork page with a masked image. “La Tragédie de Salomé,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed April 6, 2025, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1407880/la-trag%C3%A9die-de-salom%C3%A9-photograph-gerschel-charles. ↵

- “Art Information Commons: Art in Context III; Identity, Ethics, and Insight Symposium on Bias Remediation,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Library and Archives, accessed April 6, 2025, https://artinformationcommons.github.io/blog/art-in-context-symposium-third. ↵

About the Author(s): Bree Midavaine is the assistant director of library and digital strategies in the Library & Archives department at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Rosalie Hooper is the associate director of interpretation in the Learning and Engagement division at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Sophia Meyers is a collections assistant in the American Art curatorial department at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.