Classroom Patriotism

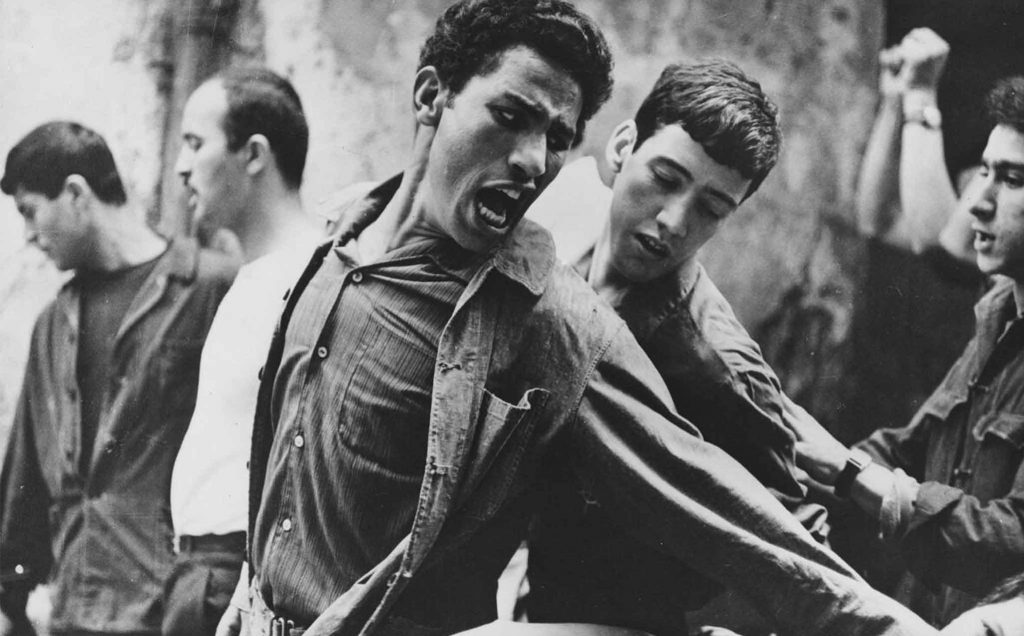

It was only a few weeks after 9/11. We were still reeling, aching inside. I was scheduled to screen a classic of Italian neorealism in my world cinema class. At the last minute, I decided the occasion called for a very different classic instead, The Battle of Algiers, a 1966 Italian film that recreates the uprising of the Algerian people against French colonial rule during the 1950s. With a newsreel-style grittiness and authenticity reminiscent of the neorealist masterpieces of two decades earlier, it depicts brutal acts of violence perpetrated by both sides in the conflict.

During a particularly disturbing scene, in which Muslim women dressed as Westerners plant bombs in crowded cafes and milk bars in the French quarter of Algiers, one of my students jumped to his feet and stormed out of the auditorium. The rest of us finished watching the movie, which includes an equally upsetting scene of military interrogators torturing Muslim men.

When I returned to my office, I logged on to a message from the student, which read, “I figured you deserve an explanation as to why I left class. With recent events as they are, to see a movie with such graphic depictions of Arab terrorism (even glorifying such activities) infuriated me. I could not sit there and watch more innocent people die. I think it was in very poor taste to choose such a movie at a time like this.”

I called him to make peace, and we talked things out. He said he comes from a military family, where patriotism is the highest form of virtue. In his opinion, the showing of that film was unpatriotic. I asked him to come to class the next day and explain his point of view. He did, and the result was a heated and probing two-and-a-half hour debate about the responsibilities of the artist in times of national crisis. I will never forget that discussion, or that student. It embodied the fair-minded, clamorous but not-hostile exchange of views that he and I, however different our political allegiances or sense of how to combat terrorism, could both feel patriotic about.

In the 1960s counterculture classic Growing Up Absurd, the progressive educator and social critic Paul Goodman, who had taught art students at Black Mountain College, stressed that schools should encourage patriotism, rather than mock it or write it off as an opiate (in today’s terms, opioid) of the masses. He warned against letting it be hijacked by politicians, demagogues, clerics, and business leaders who exploit it for their own special interests. Patriotism, after all, is love of country, and that need not mean chauvinism or jingoism. It can also mean love of community on the grand scale and a deep appreciation of democratic values, including freedom of expression by those with whom we vigorously disagree or who don’t share our sentiments. “My guess,” Goodman wrote, “is that more pride in country is engendered by one good decision, or even one good powerful dissenting opinion [by the Supreme Court], than by billions of repetitions of the pledge of allegiance.”1

Patriotism can involve loving one’s homeland for the diversity of cultural enclaves it encompasses, while not excluding the rest of humanity or claiming the superiority of our homeland to every other on earth. To be sure, global thinking (in the form of economic globalization or cultural imperialism) has a lot of negative baggage attached to it, but having a cosmopolitan outlook should be encouraged in tandem with patriotic thinking, not seen as its opposite.

Two years after the classroom incident, when the student had graduated and moved on, he mailed me a newspaper clipping. “Professor,” the accompanying note read, “I bet you’ll like this!” And I did. It was a report that the Pentagon had screened The Battle of Algiers for high-ranking officers and military strategists who were being deployed to Iraq to help them understand not only the guerrilla tactics of the insurgents, but also their festering grievances, bred from centuries-old exploitation by the West and their own governments.

In talking about art of the past with our students, perhaps the most patriotic thing we can do is allow them to work through their respective and often deeply held convictions about their nation, whether they are proud of it or ashamed, in a way that encourages dialogue rather than stifles “incorrect” viewpoints.

In that non-proscriptive environment, they can explore the ideas and pent-up rage of their ideological opponents and discover for themselves what kernels of longing and logic are embedded in political positions they have been taught to abhor.

True patriotism demands nothing less.

Cite this article: David Lubin, “Bully Pulpit: Classroom Patriotism,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 3, no. 2 (Fall 2017), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1611.

PDF: Lubin, Classroom Patriotism

Notes

- Paul Goodman, Growing Up Absurd (New York: Vintage Paperbacks, 1960), 114. ↵

About the Author(s): David M. Lubin is the Charlotte C. Weber Professor of Art at Wake Forest University