Disability and Creativity: David Drake’s Vessels and the Art of Collaborative Craft

PDF: Van Horn and Wright, Disability and Creativity

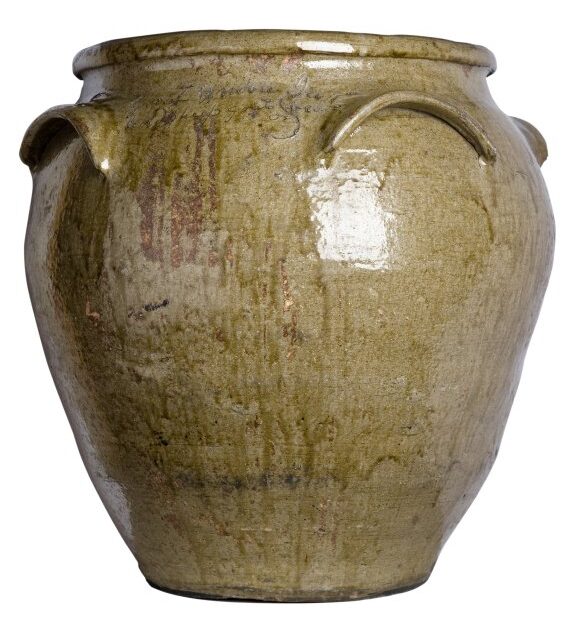

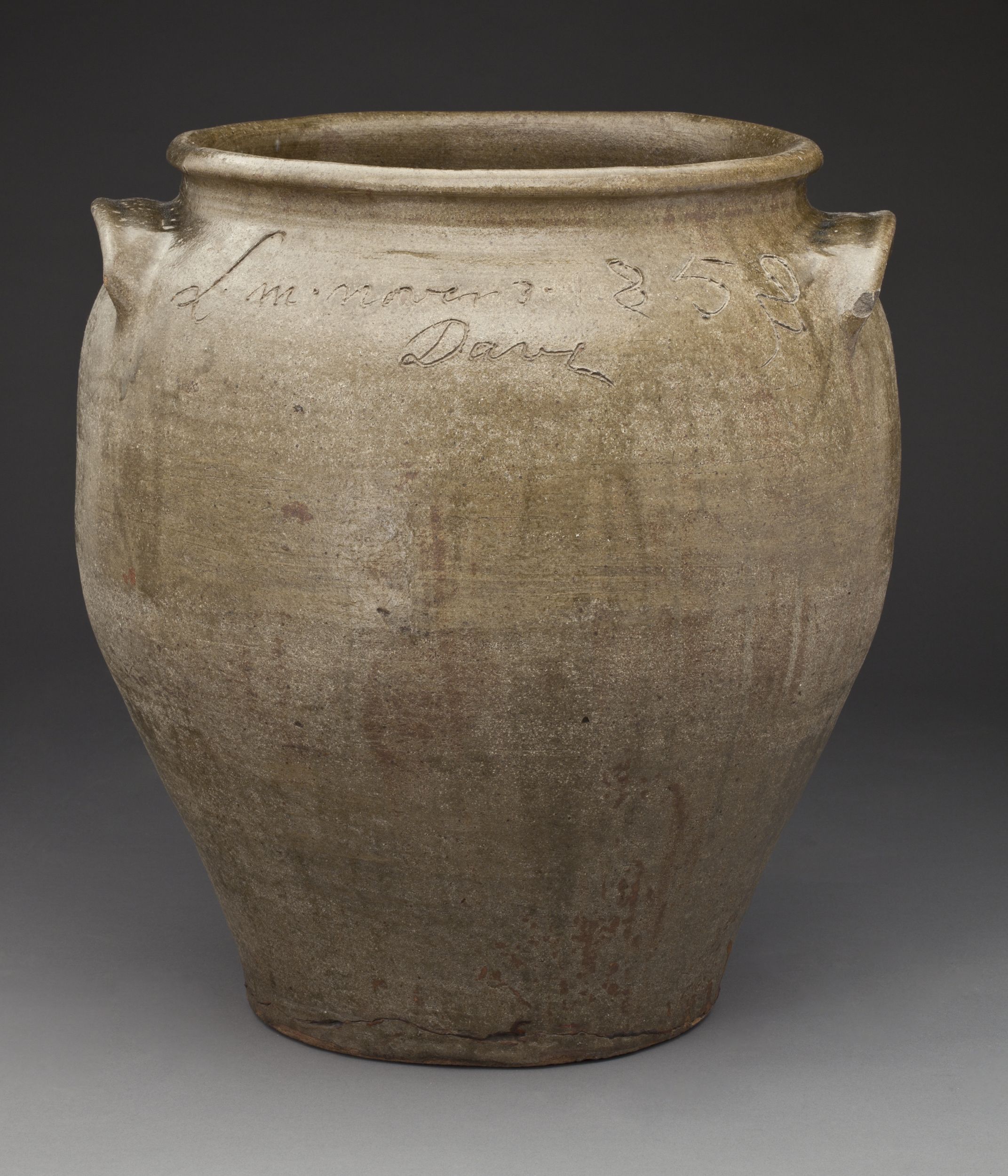

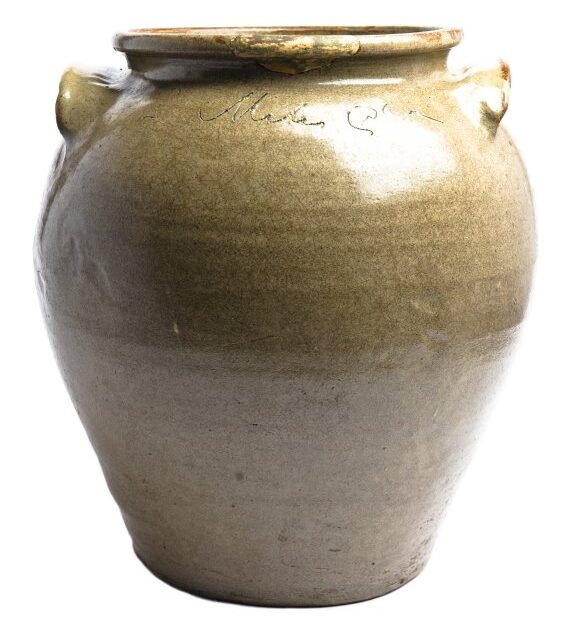

In August 2021, a stoneware jar created by David Drake (c. 1801–c. 1870), an enslaved potter from Edgefield, South Carolina, set a new record for the highest price paid at auction for a work of American pottery (fig. 1).1 The current rise in demand for Drake’s works and the corresponding prices his vessels are now commanding at auction have drawn attention from the public and spurred renewed interest from scholars who are presenting fresh interpretations and explorations of Drake as well as of the long-neglected community of African American makers with whom he worked and lived before and after emancipation.2 A recent traveling exhibition, Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina, organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston (2022–24), attests to these efforts and to museums’ ongoing work to increase the inclusivity of their collections by heightening the diversity of the artists and makers represented.3

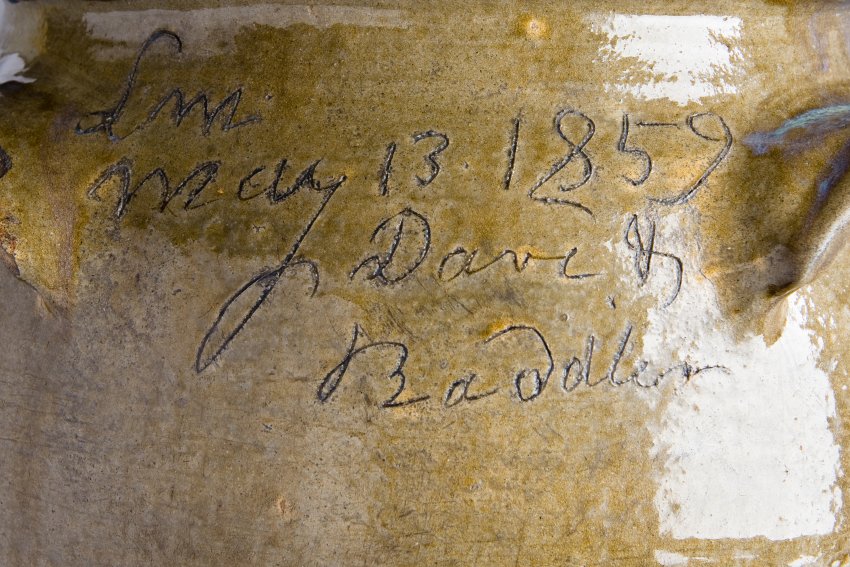

To date, the primary focus of much of this scholarship has been the lyrical words Drake inscribed on his monumental pots—inscriptions made at a time when it was illegal in South Carolina to teach enslaved people to read or write. An example is the large storage jar of 1858 (fig. 2) that bears his signature, “Dave,” along with the date of production and his enslaver’s initials, “LM,” on one side and a verse on the other: “I saw a leopard & a lions face / then I felt the need—of grace.” Drake’s vessels have been studied as an act of resistance, as a site of communication with other enslaved people of African origin and descent, as a politically charged articulation of Black skill, as part of African American craft tied to ancestral traditions, as a product of industrialized ceramic production, as an artifact of religious faith, and as a vision of an emancipatory future.4 These are all important insights, but overlooked in these discussions are issues surrounding Drake’s status as a multiply marginalized disabled maker.

Drake’s disability and its impact on his art making merit further attention. An 1873 newspaper account, written near the presumed year of Drake’s death, identifies Drake by his disability: “the veteran one-legged Dave Drake.”5 At this time, we do not know the exact date when Drake experienced limb loss or the circumstances in which this occurred, and there is a possibility that we never will. However, the 1930 oral history of eighty-five-year-old formerly enslaved African American potter Carey Dickson (earlier called Posey) claims that this event occurred within Drake’s enslavement and before his labor for Lewis Miles. Dickson recalled (using the harmful language for disability of the time): “He [David Drake] used to belong to old man Drake . . . and it was at that time that he had his leg cut off. They say he got drunk and layed on the railroad track. Later Dave went to Mile’s Mill. After Dave was crippled he had Henry Simkins, who was crippled in the arms, to drive the wheel for him.”6

The cause of Drake’s limb loss was recently and publicly disputed. When the Hear Me Now exhibition’s curators put forward the possibility that Drake’s enslavers violently caused his disability through dismemberment, a group of Edgefield-based historians and artists countered with the story of the railroad accident—a historical narrative that the curators argued is shaped by racial stereotypes and perpetuates apologist notions of slavery as a benevolent institution.7 We acknowledge the importance of recognizing violence as an endemic part of enslavement. However, in this essay, we set aside speculation about the cause of Drake’s impairment—which even Dickson verbally distanced himself from (“they say”)—to consider an understudied aspect of Drake’s life: the impact his disability had on his ceramic production. We reconsider Drake as both a disabled and an enslaved maker. We do so in the spirit of disability studies and its associated tenets of disability justice and pride, which hold that disability is not inherently negative but rather a complex, nuanced, embodied, and socially constructed experience.

Examining Drake’s surviving vessels, we ask how his practice of making evolved after the loss of his limb and how his artistic practice changed to accommodate a comaker—oftentimes the enslaved Henry Simkins, who also had a limb difference that affected his arms. By seeing Drake as a multidimensional maker who worked with Simkins and others in his community to create pots collaboratively, we follow the example of the Hear Me Now exhibition, which emphasized collaborative making, for instance, by listing the names of hundreds of Edgefield potters at the gallery entrance of the MFA’s installation.8 Here, we recover the fundamental importance of disability to this collective and to an understanding of Drake’s creative production.

Today, many viewers who encounter Drake’s work see the vessels as evidence of his body and strength—and his alone. Viewers frequently conjure a figure defined by his musculature.9 Historian Vincent Brown describes such a reaction in his essay for the Hear Me Now catalogue: “On its own terms, [the pot] is an impressive object. Solid, heavy, with elegant curves rising from a sculpted torso out to broad shoulders that support a handsome full-lipped mouth. It looked as strong as the muscles it took to make it.”10 The scale of Drake’s pots, which often required about forty pounds of clay and stand over two feet tall, invite this anthropomorphic projection, which heightens their numinous qualities by alluding to Drake’s missing corporeal presence.11 Yet in viewing the Drake vessels as a body—and specifically as reference to his body—it becomes difficult to make room for other creators who worked with Drake.

As Brown’s description suggests, Drake’s masculinity (as defined by his musculature and strength) is also often invoked.12 Decorative arts scholars frequently refer to Drake’s works as “monumental,” calling attention, as Brown did, to the sheer power required to work that much clay. The capacity marks inscribed on Drake’s pots, connoting how many gallons they could contain and store, also materially gauge the vessel’s size and Drake’s skill. These small dashes are visible to the right of the first line of text on an 1859 Drake vessel, appearing almost as quotation marks (figs. 3–4).13 “Capacity” in a disability context carries additional meaning. It has been such a ubiquitous measuring stick for physical and intellectual disability that recently scholars such as Jasbir K. Puar have defined disability as a continuum between debility and capacity.14 In this framework, capacity is the opposite of disability. When Drake’s capacity is tied to the measurements on his vessels, then this perception works to “overcome” his disability and obscure it. The overcoming occurs in part because the pots invite imagery of shoulders, faces, lips, and torsos, leading viewers to imagine Drake’s upper body and not his lower body. We only have half of the picture.

Including Drake’s disability into his figuration makes possible a more complete accounting of Drake’s collaborative practice. In this essay, we find Simkins’s presence in Drake’s early wheel-thrown vessels, and we argue for the importance of collaborative practice in Drake’s later work with other potters, including Baddler, Mark, and Abram. These collaborations, in the case of Baddler, resulted in Drake’s largest-known coil-built vessels. While collaboration is a facet of industrial-scale ceramic production, it is also a vital and necessary aspect of disability epistemology in how it shapes ways of being and knowing.

Attending to Drake’s individual skills as a potter and a poet—which are undeniable and should be celebrated—only accounts for his identity as an enslaved craftsperson and the ways in which he used his skills to counteract and transcend industrial slavery. In the masculine model of self-emancipation, autonomy is the ideal, and disability exists solely as a form of violence. This violence is seen as something to be resisted and/or as a force that spurs retributive acts of refusal and denial.15 The celebration of an individual artist also fits neatly into contemporary art markets and institutions. Scholars, however, are now looking to disability as a way of breaking apart this hegemonic viewpoint. In her recent work on disability and creativity, Elizabeth Guffey has, for example, examined the sculptural practice of French Impressionist artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir and how it changed when rheumatoid arthritis meant that he could no longer use his hands. He, too, ventured into collaborative art making. Rather than take away from Renoir’s artistic skill, Guffey turns our attention to the movements and communication between multiple creators.16

To offer a new view of Drake’s collaborative production that foregrounds disability, we build on Guffey’s work as well as important recent studies by historians focused on the complex intersections between disability and enslavement. Fundamental also is the rich literature on material culture studies of disability and the interrelated study of design and disability history, much of which is focused on the twentieth century to the present.17 We seek to complicate assumptions about authorship and art-historical narratives about Drake, which draw formal and thematic comparisons between Drake and contemporary ceramic artists and construct lineages of decorative arts study that place Drake’s vessels in relation to other ceramics of a similar type from the same region in order to resituate Drake as a disabled craftsperson. Moving disability from the periphery of Drake’s narrative to the center of his creative and collaborative praxis illuminates the racialized nature of disability in relation to enslaved artisanship in the nineteenth-century United States. More broadly, we offer a meditation on the possibilities of a materially based critical consideration of disability, unfreedom, and creativity that moves beyond analyses based on assessment of singular authorship, productivity, value, and gain in order to recover collaborative forms of making that enabled modes of expression predicated on and happening within—yet still distinct from—extractive labor systems.

The Power of Naming and the Limits of Scholarship

As we begin, it is important to articulate our choices about naming and terminology, our approach to sources and their limits, as well as our positionalities in this retelling of enslaved disabled craftspersonship. The act of naming the enslaved artisan David Drake is complex. Many scholars and curators, including those in the Hear Me Now exhibition, advocate for using the name “Dave,” since this is the way the potter signed his vessels. Others refer to the potter as “David Drake,” since this is the name given in the 1870 census, the first in which he was listed. Important questions remain as to when the potter adopted this surname (it is that of an early enslaver) and whether he did so willingly, as well as whether the name “Dave” was imposed on him or was his preferred name. Both names, one inscribed by the potter before emancipation during craft production, one articulated to a census taker after emancipation, could potentially represent the potter’s naming of himself or constitute a name imposed on him. As scholars have shown, while enslaved people bestowed names that invoked cultural traditions as well as names that connected families and community members across generations, they did not consistently have the power to name themselves. Additionally, enslavers often did not honor their names, renaming enslaved people upon purchase or refusing to record their surnames. Moreover, the white supremacist practice of referring to African American adults by patronizing nicknames and omitting surnames continued in the post-emancipation South.18

Both of the contemporary naming conventions, “Dave” and “David Drake,” are guided by the desire to honor the potter’s agency and to deploy the social recognition of his name as a means of recuperation.19 In this essay, we use the name the potter adopted legally post-emancipation, David Drake. For us this name is both a form of redress and a critical tool, since it calls attention to the constructed nature of the potter’s signature on his vessels. Distinguishing between “David Drake” and “Dave” highlights the distance between Drake’s lived experiences and the author/artisan’s public persona that he intended for circulation beyond Edgefield’s potteries. As we argue, “Dave” can be viewed as functioning similarly to an amanuensis as well as a craftsperson’s “mark”; it tied Drake (and usually Drake alone) to the verses he incised as well as to the pots that he cocreated.20

We also consider Drake as a disabled maker, conceding the complexity of the term “disabled” when applied to an enslaved person of African descent in the nineteenth-century United States.21 Drake’s enslavers, similar to those throughout the American South, assessed enslaved people according to an ableist system of racial capitalism, in which value was predicated on presumed age, gender, and potential for physical and reproductive labor as well as skill. This system led to categorizations of disabled enslaved people as “unsound” or “unfit,” which resulted in their diminished value.22 By reclaiming Drake as a disabled maker, we activate disability as a critical approach to move beyond notions of value tied to commercial exchange and to situate Drake in relation to the analytical category of disability. At the same time, we recognize that the complex entanglements between Blackness and disability have long been neglected. As many scholars, including Christopher Bell, Therí Pickens, and Anna Hinton, demonstrate, disability studies as a field of inquiry has privileged and presumed whiteness while failing to consider the full impact of race on unequal framings of disability. It particularly fails to account for the lives and strategies deployed by Black disabled people in the light of racial injustice.23 Our work builds from calls to formulate what Christina Visperas describes as “alternative or counter-narratives against ableism, heterosexism, capitalism, and racism.”24 We are indebted to the vital work of thinkers in Black disability studies who seek to establish a praxis for the ethical study of Black disability even as they work toward larger inclusion in disability studies as a whole.25

Related to these efforts to increase equity, it is important to acknowledge our shared positionality as two white authors who have different and complex relationships with disability but who currently do not identify as disabled. It has been a pleasure to coauthor an essay that is fundamentally about joint authorship and creation as vital facets of disability and creativity, and we believe that our parallel act of creation has given us insights into collaborative processes of making. Yet our own experiences as coauthors are unquestionably shaped by our positions of privilege. We have and continue to critically interrogate the multiple differences between our lived experiences and those of the Black disabled makers about whom we are writing.26

Like all who engage with histories of enslavement, we confront absence. The approximately 270 vessels attributed to Drake that are now known (about forty of which bear verses) stand in stark contrast to the silence of the archival record. There are real limits to the information that survives, not only about the lived experiences and craft practices of enslaved people in the nineteenth-century South but even about their identities. The names of many enslaved craftspeople remain hidden in what scholars have identified as the tainted archives of slavery, records produced by enslavers and slave traders to facilitate racial capitalism and oppression. In the case of Edgefield potters, enslaved people typically appear in government censuses, probate inventories, wills, and records of sale, documents made to fulfill the legal and economic concerns of the state and of white pottery owners and enslavers. Since the “discovery” of Drake’s vessels in the 1920s, cultural-heritage practitioners, dealers, scholars, citizen historians, and descendants (both Black and white) have conducted exhaustive searches into these records to piece together a more complete picture of Edgefield’s Black potters—recovery work that continues today.27

By drawing attention to Drake’s collaboration with Simkins, this essay demonstrates the need for more research to expand this important work. Similar to the uncertainty surrounding when exactly Drake lost his leg, we also cannot definitively state the length of Drake and Simkins’s partnership. This necessarily limits our ability to identify any specific vessels that they created together and, therefore, any material traces of Simkins. One day we hope more information about Simkins, as well as those turners with whom Drake later collaborated, will surface. In this essay we offer a materially informed and archivally grounded—yet nevertheless speculative—reframing in which disability is the guiding theoretical lens. We heed Hear Me Now cocurator and scholar Jason Young’s call to explore “the history of Old Edgefield pottery in such a way that democratizes and expands debate, rather than closing off conversation or privileging any single point of view or interest group.”28 Invoking artist/curator Theaster Gates’s words “to speculate darkly,” we view speculation as an important part of what has moved scholarship on Drake forward since its beginnings, and we see our work as a continuation of that effort.29

Our essay follows the powerful examples of Black feminist scholars Saidiya Hartman and Marisa Fuentes, who argue for the need for scholars to approach archives differently and to read across them holistically in order to creatively and ethically address absence.30 We painstakingly reconstruct and carefully imagine what we can of Drake and Simkins’s shared practice of craft in order to consider the implications for their vessels and for histories of disabled Black and enslaved craftspersonship broadly. Building from fragmentary sources—including Dickson’s 1930s interview describing the Drake/Simkins working relationship, a later photograph of a Black South Carolina potter at work, labor contracts negotiated with Edgefield potters post-emancipation—together with the vessels themselves, comparative examples of other makers, and theories of craft, making, and the senses, we locate collaboration, creativity, and disability across archives, be they documentary, visual, or material.

Also guided by Hartman and Fuentes, we hold space in our essay for Drake’s and Simkins’s individual personal subjectivities while remaining attentive to the limits of our knowledge. The verses Drake inscribed have sometimes provided authors with a false sense of unrestricted access to Drake’s feelings. We are mindful of Drake descendant Pauline Baker’s words that Drake “was still disguising how he felt.”31 For instance, Drake did not comment on his disability in any of his verses. By limiting our analysis to the work of these two enslaved disabled makers, we refuse to project our words or emotions onto these men and thereby risk reinscribing the systems of oppression under which they created.32

Disability, Enslavement, and Artisanship

There are many ways in which Drake was and is exceptional. Drake’s literacy and the verses he inscribed, as well as the size of his vessels and the exemplary skill evidenced in their making, all contributed to Drake’s status as a remarkable craftsperson and have fueled the renown that Drake and his work have garnered in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. However, the fact that Drake was a disabled enslaved artisan was not exceptional. Craft and disability were frequently conjoined in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Making was often disabling to artisans, typically due to exposure to hazardous materials, and it was recognized as such in the period. For instance, the London Tradesman, published in 1747, warned that carpenters, house painters, and glaziers were “subject to the Palsey more than any other Trade” due to “much handling of Lead.” Similarly, the author enjoined that pewtering “is an ingenious Business and abundantly profitable, but very unhealthful, because of the Fume of the Metal, which soon renders them [pewterers] Paralytic.”33 Potters too faced exposure to lead, in the form of glazes, as well as to airborne particles of silica (from clay), which resulted in lung disease.34 Enslavement itself was also often disabling, given the physically taxing work that enslaved people did, as well as enslavers’ propensity to acts of violence and their legal impunity from withholding medical care or failing to provide adequate nourishment, clothing, or heat. Nondisabled enslaved people were part of the “pre-disabled,” to borrow the term from French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, meaning those who historically have faced the most physical and psychological risk due to race, class, and nationality.35 Moreover, artisans routinely assigned enslaved people work that was the most dangerous and entailed the greatest exposure to unsafe materials within a given workshop.36

Enslaved people’s skilled, although forced, labor contributed to virtually every craft in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century United States, in urban centers, rural towns, and plantations.37 As one Virginia enslaver noted, his plantation was the workplace for enslaved “carpenters, coopers, sawyers, blacksmiths, tanners, curriers, shoemakers, spinners, weavers and knitters, and even a distiller.”38 Ongoing scholarly and digital public humanities efforts, most notably Tiffany Momon and Torren Gatson’s Black Craftspeople Digital Archive, are doing incredibly important work to recover the names, expertise, and contributions of enslaved craftspeople of African origin and descent in North America.39 However, thus far, physical impairment has not factored into scholars’ thinking as a condition that encouraged enslavers to train enslaved people in the “art and mystery” of a craft. Historians Dea Boster, Jennifer Barclay, and Stefanie Hunt-Kennedy argue that despite enslavers’ and slave traders’ low monetary evaluations and characterizations of individuals with mental and physical impairments as “unfit,” they nevertheless found many ways for disabled enslaved people to contribute to their profits. Because the loss of lower limbs meant enslaved people could not perform field labor or work that required standing, disability seems to have been an incentive for training men in a craft, particularly skilled work performed while seated, such as shoemaking.40

The choice to train men, rather than women, in trades was consistent across the South. It stemmed from gendered ideas of craft persisting from guild structures in Europe, as well as enslavers’ propensity to deploy women as field laborers and in skilled domestic work, such as textile creation, that did not require the same kind of artisanal training. Enslavers’ decisions about craft had significant outcomes for self-emancipation and for perpetuating racial capitalism; enslaved craftsmen had more opportunities for mobility and financial gain than enslaved women, who had fewer, if any, choices to purchase their own freedom or to free themselves. Because children’s status followed their mothers’, this helped sustain unfreedom generationally.41

Two examples illuminate the kinds of personal trajectories that led enslaved disabled men to the craft of shoemaking. William Lee, an enslaved manservant to George Washington, suffered injuries to both knees in the 1780s during his service to Washington, including valeting and assisting him in surveying. As a result, Lee was unable to stand and therefore to perform his assigned duties during Washington’s presidency. After sending Lee back from New York (which was then the capital) to his Virginia plantation, Mount Vernon, Washington had his former valet trained in shoemaking, a craft that Lee could undertake despite his limited mobility. By 1791 Lee repaired and created shoes for the people enslaved at Mount Vernon, a sizable task; he produced approximately 334 pairs of shoes in 1794 alone.42 Formerly enslaved shoemaker and Methodist minister James L. Smith recounted his experiences of disability and craft training in his published narrative. Also enslaved in Virginia, Smith injured his knee in childhood. He wrote, “Being lame I was not very profitable on the plantation,” which led his enslaver to have him “learn the shoe-maker’s trade” at the age of eighteen.43 Despite Lee’s and Smith’s designation as “lame” (Washington used the term for Lee in his 1799 list of those people he enslaved), both men were skilled and active craft practitioners. Indeed, in Smith’s case, shoemaking sustained him after he self-emancipated, and he passed the craft on to his son.44 Whereas Smith, like many self-emancipated or manumitted artisans, leveraged his craft for his own benefit, enslavers anticipated that they would reap the economic benefits of training disabled men in shoemaking. The commonality of this approach is suggested by physician W. H. Robert’s reassurance to white readers of a Southern medical journal that after Robert amputated the leg of an enslaved teenager, his enslaver did not “sustain . . . any loss, for he has made him a cobbler.”45

David Drake and Henry Simkins, Disabled Makers

Unlike assigning enslaved men with disabilities to train in shoemaking, the practice of teaching them to become ceramic producers does not seem to have been a frequent strategy. Keeping in mind that we do not know exactly when Drake’s limb loss occurred, it seems most likely that Drake had already trained as a potter before his injury. While the circumstances of his early life, including the nature of his training and the date of his lower-limb loss, remain uncertain, historians believe that he was already working as a potter or “turner” at the wheel before his amputation. Drake’s earliest known inscribed vessel is dated to 1834, and the earliest date scholars have proposed for his injury is 1835.46 Drake then was a knowledgeable artisan who became disabled rather than a disabled person who was assigned to learn a craft. It is significant that this disabling event is generally thought to have preceded his most prolific period of creation: while Drake was enslaved by Lewis Miles from 1849 until his emancipation after the Civil War in 1865.47

To some extent, ceramic production was similar to shoemaking in that it relied on upper-body strength and the manual dexterity of the maker’s hands and arms, identifying it as a craft that could accommodate a creator with a lower-limb injury. However, it also at times depended on a foot-driven technology: the treadle that spun the potter’s wheel, which allowed a maker to use both hands to shape the clay and form it into a vessel. To get an idea of the kind of foot-driven treadle that Drake and other turners used in Edgefield’s potteries, we can look to a rare surviving nineteenth-century example used in the shop of Massachusetts potter Hervey Brooks. Brooks’s potter’s wheel consists of a simple wooden frame with a wheel for throwing pots connected by an iron crank to a kick wheel at the bottom. In their search for evidence of the shop practices of enslaved Edgefield potters, ceramic scholars have turned to a series of photographs of African American potters working in South Carolina in the early twentieth century. A photograph of Black potter Rich Williams, who created vessels that have been compared to Drake’s, documents a handmade wooden-framed standing kick wheel in his shop (fig. 5).48 Whereas Brooks’s wheel was designed for a seated user, Williams’s was intended for a standing or partially standing maker, suggesting that the wheel that Drake used was likely also wooden-framed equipment intended for a standing turner.

If it was the case that Drake used equipment for a standing potter, then the amputation hampered Drake’s ability to power his own wheel. The solution for him to continue his trade was one common across the South for disabled enslaved laborers: forced partnership with another disabled person so that the pair could complete tasks difficult or impossible for either individually. Dickson’s oral history described Drake and Simkins’s working relationship (again, using the harmful language of the time): “After Dave was crippled he had Henry Simkins, who was crippled in the arms, to drive the wheel for him.”49 This labor arrangement recalls similar assignments across the plantation South, including at Mount Airy plantation, Virginia. As Barclay details, there “Lame Sam” and “Blind Tom” were assigned to work as a pair; Tom was a skilled carpenter, and after his impairment, the men worked together as millers and ginners.50

Scholars have spent eighty years carefully gleaning what they could about the details of Drake’s life. By contrast, Simkins remains understudied, as do the approximately two hundred enslaved and free Black men, women, and children—bound together by intergenerational knowledge of their craft as well as their personal and familial ties—who made up the workforce in Edgefield’s numerous thriving potteries, which were, in turn, owned and managed by an interlinking coterie of white enslavers and their families.51 Although evidence is scant, there is nothing to suggest that Simkins ever received training in ceramic production. Instead, he was likely one of a large number of workers who undertook the variety of tasks necessary to support turning clay on the wheel, firing vessels, and transporting them for sale and distribution. These jobs included harvesting and processing clay, grinding ingredients for glaze, chopping firewood, caring for horses, loading or unloading the kiln, and driving a wagon.52 Simkins’s impairment meant that he could not participate in these tasks for his enslaver’s pottery alone. Working with Drake and learning new skills in setting a pace for production at the wheel increased Simkins’s profitability for his enslaver exponentially. And Simkins’s labor enabled Drake to once again utilize his highly valued skill in throwing pottery, which included his knowledge of materials, working with clay, and expertise with the wheel.

A view of disability based on conceptions of “wholeness” may understand Simkins and Drake to “complete” each other, with Drake acting as the upper body and Simkins as the lower. This framing, however, perpetuates racial capitalist and ableist assumptions of bodily “fitness “and “lack.” For instance, in their assessments of enslaved people, nineteenth-century slave traders and enslavers mapped economic productivity (and therefore assessed value) using metaphors of “whole” and “partial” bodies centered on “the hand.” An enslaved person labeled as a “hand” was someone who could complete the maximum amount of physical labor possible in a day. In labeling someone as a “half hand” or “quarter hand,” assessors referred to those who had diminished productive value, whether because of age, illness, or lack of knowledge. According to this ableist mindset, Drake and Simkins were “half hands” who, due to their labor assignment, could come together to constitute a full “hand.”53

Drake/Simkins and Wedgwood/Bentley

While it is helpful to understand the assigning of Simkins to drive Drake’s wheel in the context of enslavement, this collaborative model also incorporated disability into long-standing arrangements of hierarchical cooperative labor, common in large pottery manufactories, that paired workers with different skills. Beginning in the eighteenth century, at pottery manufactories in Staffordshire, England, for instance, potters’ wheels were often powered by a “great wheel” similar to the wheels used for lathe turning (also a part of pottery production). These independent wheels were not set into motion by the potter but by young assistants or children who lacked the strength or bodily knowledge required for throwing pots.54 In one famous instance, a great wheel facilitated the work of another disabled potter: Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795). The British pottery entrepreneur contracted smallpox early in his life, which resulted in complications to his right lower leg such that he chose to have it amputated. Employing a great wheel at his factory in Etruria, near Stoke-on-Trent, England (possibly the surviving example in figure 6), Wedgwood threw pots after his amputation with the aid of his business partner, Thomas Bentley, a man not trained in ceramics but who was able to power the wheel.55 These pots are known today as the First Day Vases. Further research is required to establish how Wedgwood’s use of a great wheel as a disabled potter was related to his well-studied efforts to accelerate ceramic production, develop a marketable aesthetic, and streamline the process of making at Etruria to increase economic profit.56 There are, of course, significant differences in racial, legal, and social status between Wedgwood and Drake. For our purposes, Wedgwood is important as a comparative example of a skilled turner who adapted existing shop practice and reconfigured inaccessible industrial technology for his own needs. Wedgwood encourages us to see his ceramic vessels, and Drake’s later pots, as part of a longer process of ad-hoc design intervention charted by scholar Bess Williamson, in which disability can engender new modes of making and thinking that are generative rather than prohibitive.57

We are not the first to invoke Wedgwood and Drake together, though in the work of past scholars, this comparison has been founded on white-centric histories. In his book on Drake, Leonard Todd (a descendant of Drake’s enslaver Reuben Drake) imagined someone reacting to news of his leg amputation by saying, “Tell him it will make him a better potter, poor boy! Remind him about Josiah Wedgwood!”58 For Todd, the correspondence between these two potters’ disabilities cast Drake as someone who could aspire to Wedgwood’s success. This approach parallels the technologically based idea of progress and attitudes of Edgefield’s white pottery entrepreneurs and enslavers, who looked to English ceramic producers, including Wedgwood, for models of how to create industrial regional pottery enterprises. Indeed, Abner Landrum, often hailed as the progenitor of Edgefield’s potteries, named one of his sons after Wedgwood.59

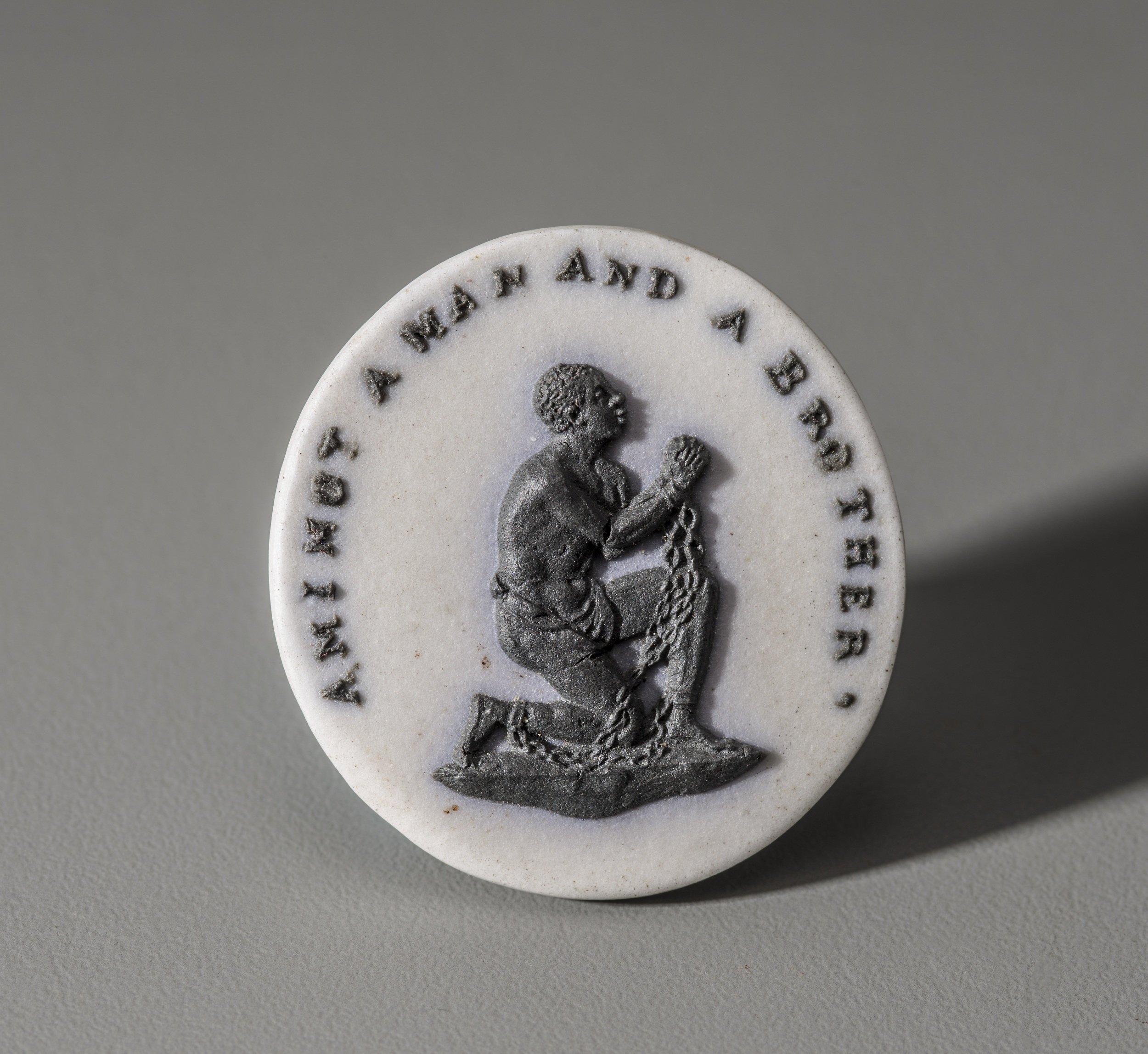

We would like to shift focus, instead, to consider Wedgwood through Drake. In other words, how might the two potters’ shared disability, combined with their differing statuses, change how we approach one of Wedgwood’s most famous creations, the “Am I Not a Man and A Brother” antislavery medallion based on a seal commissioned by the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade (fig. 7)?60 Unaker or “Cherokee” clay from North and South Carolina played a vital role in Wedgwood’s experiments with, and in his recipes for, both encaustic glaze and jasper, connecting the medallion’s materiality with the geography of Edgefield.61 The figure of the kneeling man is notably nondisabled; only the chains represent debility. This figure was reproduced countless times in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Because of the Wedgwood medallion’s importance to the abolitionist movement and antislavery visual and material cultures, his figure also evidences the strong connection between the nondisabled enslaved body and resistance—a connection that we continue to witness today in narratives about Drake’s creations as acts that resist, by extension, his disability.

While the work environment in Edgefield’s potteries is less documented than Wedgwood’s Etruria, at both sites manufactory owners shared an emphasis on industrializing processes of making in order to achieve profit through the quick production and wide distribution of ceramic wares.62 Edgefield’s potteries relied on an overwhelmingly enslaved labor force; however, evidence suggests that there was a hierarchical arrangement familiar from earlier pottery manufactories. An 1866 labor contract between Edgefield manufactory owner Benjamin Franklin Landrum and African American men and women turners Simon, Dave, Sam, Selia, Kittie, and Ann, as well as children Wash, Jack, and Adam, indicates a pairing of skilled and less skilled workers. The agreement stipulated: “I, Simon, on my part agree to turn what is known as ‘the long day’s work,’ a boy being furnished to assist me.”63 Simkins and Drake’s pairing resonated with long-standing practices of disassociating the driving of the wheel from the throwing of clay for purposes of economic gain and of modifying tools or technologies to accommodate disabled potters. Drake and Simkins’s labor arrangement, formed in relation to Edgefield’s enslaved workers, also coincided with traditional arrangements in which people without skills as potters provided assistance to turners at their wheels.

Aurality and Communal Creation

David Drake utilized a variety of methods to produce ceramic vessels of varying sizes and forms across his decades-long practice. In the following sections we consider what scenarios of joint work at the wheel might have looked like. Together Simkins and Drake approached the question of how to reformulate Drake’s past practice of potting to include Simkins’s direction of the wheel. Potters require the wheel to remain predictable and to move slowly as they center the clay and then to spin with greater speed as they raise the walls of the pot. If the speed of the wheel is too fast, if the pressure of their fingers too strong, or if these factors are not in concert, then the pot will twist or torque. As Jenni Sorkin, a scholar of later twentieth-century ceramics, describes, in “wheel-thrown vessel[s], . . . the body of the craftsman, through his or her physical manipulation of the clay, determines the size and shape of the most intimate spaces of the vessels itself: its girth and weight, the delicacy of the rim, the strength and placement of a handle.”64 Like all skilled potters, Drake had developed what design historian Kate Smith labels the embodied knowledge critical for production.65 Before his injury, Drake could use his body as a mechanism to control pacing: because his foot movement set the wheel’s tempo, physical sensation allowed him to match his upper body movements to the speed of the wheel. Like other craftspeople, Drake was skilled at corporeal anticipation, predicting what the clay would do next and using his body to create conditions in which the clay moved as he wanted it to in order to fulfill the conditions needed for the next step of making. As Richard Sennett describes, the rhythm of making consisted of both a beat and tempo (created by the press of the foot against the treadle) and the corresponding speed of the wheel turning, a constantly shifting rhythm that anticipated future need.66

The addition of another person who determined the wheel’s pace meant that the tempo of making, at least initially, had to be communicated externally. While we do not know exactly what system the men used, given the fact that Drake was using both of his hands, we believe it likely that his cues to Simkins were auditory rather than gestural. As Smith argues, it is difficult to recover “the grunts and hand gestures that surely facilitated production practices in . . . eighteenth[-]century [potteries].”67 The vocal or auditory signaling systems used in other crafts can provide a useful comparison. For instance, a blacksmith working iron with a striker taps their hammer on the anvil a set number of times to indicate when the striker should start and stop. When working alone, individual smiths also strike the anvil (rather than the metal they are forging) as a means to maintain a constant rhythm and to orient their aim.68 Over time, as Simkins acquired expertise, it is possible that the men’s partnership evolved to a point where no communication was necessary, and Simkins’s embodied knowledge enabled him to anticipate Drake’s need for greater or lesser speed. To follow that line of thinking, we want to make space for Simkins’s influence on the process of joint creation that was itself an artistic act. To move away from hierarchies of craft and labor calls for critical examination of which actions are considered skilled or unskilled and to acknowledge multiple forms of creative action and knowledge.69

Looking again at Drake’s lathe-raised or finished storage vessels, we see them as the physical manifestation of a multipart coordination—physical, material, mental, and auditory—distributed across two bodies and one wheel. In this way, historian Katherine Ott’s observation that “objects document movement” and enable scholars to “restore that lost knowledge [of] people in motion, especially bodies that move in unconventional ways” can reveal Drake’s vessels as material records of his and Simkins’s disabled making—the power and pace provided by Simkins’s foot and the applied pressure directed by Drake’s arms and fingers.70 Or, to orient the vessels in a different sensory plane, we might think about “listening” to their pots, becoming attuned to the interplay of sound and movement that registered in the rotating clay. Building from scholars’ observation that Drake delighted in sound combinations—as evidenced in many of the verses he inscribed—scholar Shelly Jarenski calls attention to the importance of the aural in Drake’s vessels. Turning to contemporary artist Theaster Gates’s (b. 1973) engagement with Drake in his 2010 art installation and exhibit To Speculate Darkly, held at the Milwaukee Art Museum, Jarenski details how Gates’s artistic response enabled greater appreciation of Drake’s aurality. Gates assembled a large gospel choir, with singers from Chicago and Milwaukee, to sing a “hymnal” that he composed for the exhibition, which included many of Drake’s verses. In this way, Gates amplified the nonocular and extratextual components of Drake’s pots.71 Scholar Tina Campt similarly articulates the ways that “listening” to photographs of African Diasporic subjects can side-step white-centric and colonialist archives intended to buttress unequal power dynamics of race and, instead, enable discovery of familial and personal connections and recognition of acts of self-fashioning and material agency. Such modes of engagement (including the haptic or tactile in addition to the aural) enable our recuperation of the depicted subjects.72

If we factor workshop practice and our knowledge of disabled making into efforts to “hear” Drake’s pots, then in addition to their explicit verses intended for Southern readers/viewers/listeners, we might also encounter a different set of utterances, sounds, and signals that facilitated communal creation. Sorkin stresses the importance of studying ceramics not as finished objects but as process, “not as commodity but as experience.”73 She illuminates how throwing pots on the wheel is necessarily a performance and a mode of creation tied to communal knowledge production and conversation. The invocation of the communal practice of blacksmithing is once again particularly salient in relation to the Black Atlantic and the rituals and rhythms that blacksmiths of African origin and descent shared across space and through memory. As anthropologist Candice Goucher demonstrates in the Caribbean and southern United States, the beat of Black blacksmiths’ hammers striking the anvil and the exhalation of the bellows that kept their forges hot provided a communal rhythm that invoked ritual and defined Black space.74 Thinking of Edgefield’s potteries as sonic spaces and recognizing creation with clay as a pliable part of performance encourage us to keep this larger sound world in mind, one in which the beat of feet on potters’ wheels and the communications between turners and their assistants facilitated Black creativity even amid racial capitalist systems of oppression and forced productivity.

Echoes of Henry Simkins

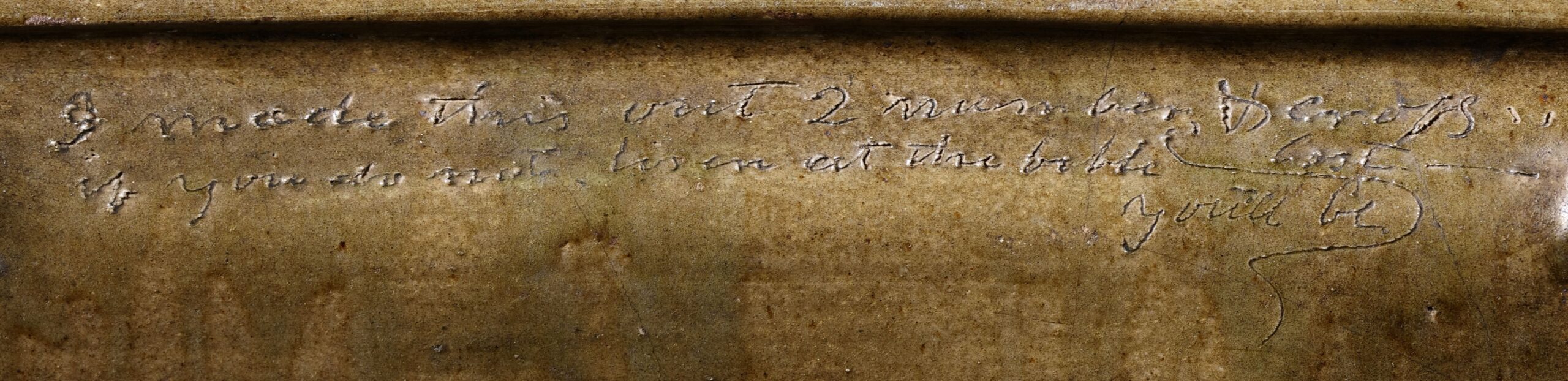

As we look at Drake’s vessels with comaking and aurality in mind, we become attuned to physical traces where Simkins’s presence perhaps can be found, felt, or heard. While the exact dates of Drake and Simkins’s collaboration remain imprecise, an early vessel in the Charleston Museum’s collection, dated July 22, 1840, and incised “L. Miles Dave,” is a potential candidate for their joint manufacture (fig. 8). Even under the alkaline glaze, the throwing rings—circular rings formed by the potter pulling up the clay—are a dominant presence within this vessel’s walls. A three-dimensional scan of an 1862 Drake vessel in the collection of the National Museum of American History (NMAH) in Washington, DC (fig. 9) enables us to vicariously experience similar throwing rings from different vantage points. (We encourage readers to take a moment to engage with the NMAH pot using this viewing device.) From inside the pot looking up, the throwing rings appear as a pulsating substructure, their undulations an active topography that channeled the rivulets of alkaline glaze and that, though now long dry, continue to animate the vessel’s interior surface. These throwing rings resemble those on earlier pots, such as that now in the Charleston Museum (see fig. 8), which were conceivably the product of Simkins’s skilled pace setting.

Fig. 9 David Drake, Storage Jar, 1862. Inscription: “I made this jar all of cross, If you dont repent you will be lost,” “May 3, 1862/LM Dave.” Stoneware with alkaline glaze, 20 1/2 x 18 in. Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Washington, DC, 1996.0344.01. Interactive viewing device: https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object/nmah_1181785

Our awareness of the auditory facet of Drake and Simkins’s making opens new opportunities for redress through sound by shifting attention from the pot’s exterior to its interior, from the inscriptions to the throwing rings, and from Drake’s prominent presence to Simkins’s faint shadow. In the throwing rings, which are rearrangements of clay’s matter generated by the motion of the wheel rotating at a pace set by the raising and lowering of Simkins’s foot, we find the muted but integral rhythm of Simkins’s body. Dwelling in the pot’s interior, we are guided by Campt’s analysis of visual and material sources that are “quiet,” meaning they engage a “lower range of intensities” that can be felt but not heard directly, such as a low hum. Reminding us that sound “is a profoundly haptic form of sensory contact,” Campt models how “quiet” material things can register both touch and sound, since sound itself is “a wave resulting from the back-and-forth vibration of particles in the medium through which it travels,” a description that recalls the throwing rings’ similar material formation and current appearance as frozen crests.75 In this analysis, sound waves and the vibrations of the potter’s wheel that thrummed with the motion of Simkins’s foot coalesce, commingle, and persist in the throwing rings.

As we consider locating Simkins through sound, the work of scholar Dylan Robinson (Stó:lō/Skwah) on Indigenous sound worlds is useful in his emphasis that listening, not just sound creation, is critical for recuperative histories. The throwing rings are also records of listening and accommodation between Simkins and Drake, because the men set a working pace that relied on mutual knowledge and necessitated bringing together their varied sensory experiences and skill sets. For Robinson, the palimpsest is a useful metaphor for listening in which “a counter orchestra of whispers” becomes perceivable not through the aural alone but in a multisensory approach that acknowledges lived experiences of movement and relationships within communities. Like Campt, Robinson argues that attending to silence, quiet, or imagined sounds can afford space for recovery.76 Their works encourage us to emphasize that Simkins’s and Drake’s physical traces on these vessels are not commensurate—there is no iconographic element or inscribed verse to which Simkins’s presence can be pinpointed as there is for Drake. Instead, by turning to alternate modes of sound—a vital force for Black life throughout the Black Atlantic—we can posit a place where he can perhaps still be felt as a low hum, a whisper, an echo.

The growth upward and outward of the turning rings also materialize cultural negotiations of time. As makers, Drake and Simkins inhabited what material culture scholar Edward S. Cooke Jr. articulates as “artisanal time.”77 Just as we probe what, and who, is encompassed within Drake’s signature, Cooke argues that inscribed dates on objects similarly further a single-authorship model by flattening an object’s creation to one stage of its completion—in this case, Drake’s turning. Drake dated many of his vessels precisely, noting the day, month, and year, alongside his signature, and he never signed a vessel without an associated date, evidencing their inextricable connection.78 The “cumulative, partially invisible, nonlinear, and episodic” nature of artisanal time accounts for other necessary tasks that Simkins and others took on outside of Drake’s turning.79

The fact that Drake, Simkins, and Drake’s other collaborators were enslaved had a significant importance for their framings and understandings of artisanal time. Enslavement severely limited their ability to set their own pace of production and heightened the urgency of their making. As Mark M. Smith and others have shown, across the South enslavers used clock time, calendar time, and recordkeeping to monitor enslaved people’s output, and together with the application of violence, they maximized production and increased their profits.80 Yet enslaved people resisted enslavers’ attempted temporal domination, for instance, by deliberately slowing down the pace of work or by hiding or breaking necessary equipment, enabling enslaved craftspeople to reframe their conceptions of work in relation to time beyond that dictated by their enslavers. Indeed, as Walter Johnson argues, enslaved people’s ability to mobilize multiple time scales (including the biblical and historical) was a major factor in communal armed rebellion.81

Resistance to enforced clock time also relates to “crip time”—the idea that disability alters experiences of time to slow some things down and speed up others.82 Scholars have already discussed the liberatory aspects of crip time in how it makes the strict, linear time of contemporary capitalist frameworks more flexible. Yet enslaved people with bodies and minds that could not conform to enforced clock time also reveal crip time’s potentially emancipatory qualities. Today, crip time is additionally used to describe feeling “out of time” with nondisabled peers. Yet the turning rings on Drake’s vessels materialize how he was “in time” with Simkins in ways that speak to the collaborative nature of crip time through interdependence. Drake and Simkins negotiated approaches to time based on their multiple identities and statuses—experiences of time that could be conflicting or harmonious but that coalesced into the turning rings that the kilns of Stoney Bluff fired into perpetuity.

“Crip ‘Things’”

A focus on Drake’s vessels as records of shared movement with Simkins called into being through auditory cues and archives of sound and alternative notions of time, rather than as completed artifacts, encourages us to bring the concept of “crip things” into our analysis. In recent lectures and conference presentations, Guffey has introduced “crip things,” which she describes as “how disabled people make art and even worlds in and through seemingly unspectacular stuff combined with choreographies of movement.”83 Using the aforementioned example of Renoir, Guffey discusses the objects that the French painter designed as aids when rheumatoid arthritis significantly limited his range of motion—a moving easel and palette. These, she argues, are “crip things,” language that borrows from Ott’s concept of “disability things,” which Guffey uses to problematize the term “mystery” as applied to disability and creativity. Returning to the so-called art and mystery of craft, our contention is that this concept of crip things is vital to histories of disability and craft. In this case, the most obvious crip thing at the center of Drake and Simkins’s choreography is the wheel. However, Drake and Simkins’s collaborative work highlights an important part of Guffey’s concept—that choreographies of disabled making are often between people and objects and not just between a single person and a given thing.84 As in the example of blacksmiths, this choreography is vital to craft in ways that reveal how both craft and disability upend hegemonic understandings of authorship.

Even as we embrace the analytical power of crip things, we also want to consider the dangers inherent in applying this concept uncritically to enslaved disabled makers in the nineteenth-century South. In South Carolina, race-based enslavement and anti-Black racism meant that people of African origin and descent had their full personhood denied and were considered by white enslavers to be things. Scholars, including Zakiyyah Iman Jackson and Walter Johnson, illuminate enslavers’ strategies of “dis-humanization,” in which they sought to deny Black personhood and assert objecthood even as they manipulated and benefitted from enslaved people’s humanity.85 In this context, the term “thing” cannot be disentangled from the ways enslavers sought to limit and control Black agency. Antislavery author Harriett Beecher Stowe famously wished to give her novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin the subtitle “The Man That Was a Thing” to highlight the legal position of enslaved people as human beings who were also property.86 Stowe attempted to open up a space of critique for nineteenth-century white readers even as her text perpetuated inequity and recycled stereotypes of African Americans as uneducated and by extension supposedly “humorous,” particularly through her use of racist dialect. Similar stereotypes and use of racist dialect appear in a period account of Drake from the nineteenth century, published in the Edgefield newspaper.87

This newspaper account lays bare the conjoined racism and ableism that constrained Drake and Simkins’s creation and through which we inevitably encounter their vessels today. To put it clearly (but painfully), in their enslavers’ view, Drake, Simkins, and the wheel were all legal property, “things” put into motion only for their enslavers’ economic benefit. To fully understand the ways that Simkins and Drake’s choreography upends hegemonic understandings of authorship requires care in how we attend to racialized systems of power. We must also acknowledge the constraints placed on enslaved people’s assertions of agency and the complexities of the resistance they enacted through material forms that linger to the present. We must consider how race intersected with crip things to allow the making of “art and even worlds.” In the last section of the essay, we return to Drake’s vessels with these directives in mind.

Beyond “Dave the Potter”

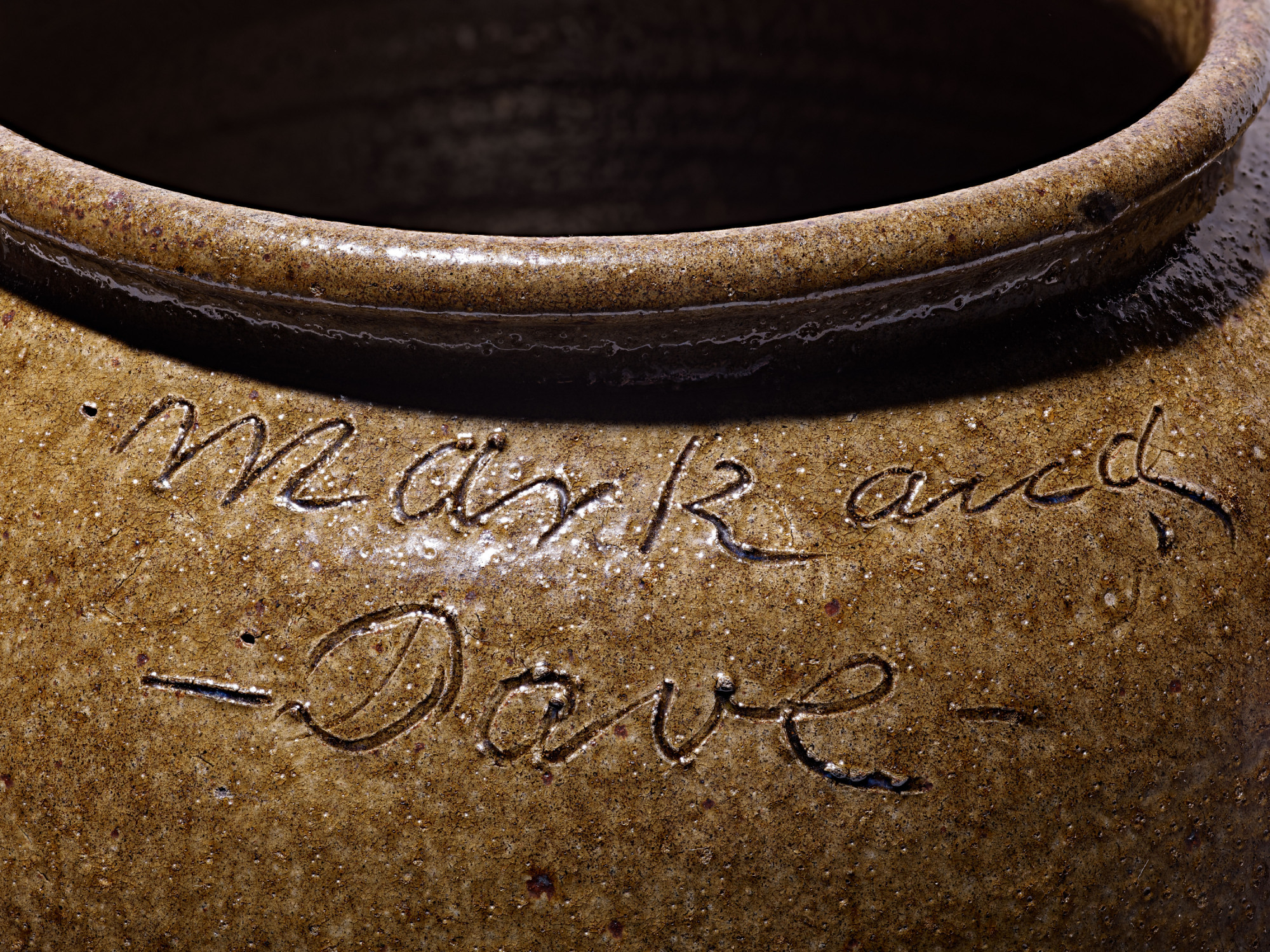

After establishing the importance of Drake and Simkins’s collaboration at the wheel in relation to disability and creativity, we can reconsider the importance of collaboration across Drake’s decades as an enslaved potter (roughly 1829–64). 1859 proves an important year, resulting in three known co-signed pots. Decorative arts scholars have long noted that two of these storage vessels may have necessitated the work of multiple potters or turners—people with the embodied knowledge of building and shaping pots on a wheel. They dwarf even Drake’s massive individually signed pots of the 1850s and 1860s, such as the 1858 example mentioned at the beginning of our essay (see fig. 1). All are significantly taller and wider than the earlier Drake pots, such as the 1840 example in the Charleston Museum that measures approximately fifteen inches in height (see fig. 8). These multipart vessels combined two different techniques. They required coil-building parts of the vessel that were then combined and further shaped and refined on the wheel.88 The seams that connect the different sections are visible in these vessels and have been used, among other characteristics, to attribute large pots to Drake.89 One ridge is especially visible in a c. 1840–50 vessel in the Chipstone Foundation collection in Milwaukee (fig. 10). These seams appear in the two aforementioned monumental jars, on which Drake identified Baddler as comaker (figs. 11–12). Here, the seams act as material manifestations of collaboration. A smaller storage jar in the NMAH collection has “Mark and Dave” inscribed on it (figs. 13–14) and was likely coproduced with potter Mark Jones, as is claimed by Corbett Toussaint, who has published the most comprehensive study of the African American potters in Edgefield.90

We would like to place those extremely successful collaborations in line with Drake’s earlier shared process of making pots with Simkins to suggest that their joint creation set the stage for Drake’s later cocreated vessels. We raise the possibility that it was the experience Drake gained after his impairment—when he had to strategize and transform the individually powered act of turning on a treadle kick wheel typical in Edgefield to include a second maker, thereby reconceiving the intuitive physical process of making a vessel into a series of verbal or auditory cues—that later enabled him to make vessels with other skilled turners. In other words, this may be an example of “disability gain.”91 Drake’s loss of a limb resulted in a corresponding gain—the formulation of a new multisensory, collaborative approach to making that was inventive and imaginative and that ultimately spurred the creation of vessels that might not have been possible for Drake before; these vessels, in the case of the Drake and Baddler pieces, had nearly twice the capacity of his largest earlier works and transcended the limitations of the traditional practice of a single turner.

This claim presents a new way to interpret Drake’s work, one that differs from what was put forth in the Hear Me Now exhibition. In that show, curators used the “Mark and Dave” vessel (see figs. 13–14) as an opportunity to discuss Drake’s disability. The label text read, “Dave’s disability required a co-worker, someone to work the pedal that rotated the kick wheel. In the case of this jar, that person was Mark, whose name appears alongside Dave’s. The two may have had a familial relationship. The 1870 census lists ‘Mark Jones’ and ‘David Drake’ as living in the same residence.” It is notable that Simkins is not mentioned, as Jones is here, in any of the other interpretive object labels. (Simkins appears elsewhere in the exhibition, on a wall of names titled “The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina,” but not in connection with Drake’s disability.) Moreover, the 1870 census mentioned in the label brings up questions about Jones’s role in the creation of this piece. The census lists his occupation as turner. Would Jones have been operating the kick wheel while Drake singularly created the vessel? This scenario prizes Drake’s individual agency and uncircumscribed creative actions. Bringing Simkins into view as someone who drove the wheel, but who was not a turner, potentially changes the dynamic between Drake and Jones, particularly considering how Drake credited (or failed to credit) collaborators.

It is significant that while Drake occasionally inscribed the names of other men—Baddler, Mark, and Abram—who were potters like himself—on his works, he never included Simkins’s name.92 Simkins’s labor then, like that of many workers, apprentices, and journeymen, white or Black, free or enslaved, male or female, was subsumed underneath Drake’s signature: “Dave.” Here, Drake seems to have perpetuated craft hierarchy. Simkins’s unacknowledged contributions as someone who “drove the wheel,” in Dickson’s words, became part of Drake’s construction of a singular masculine artisanal identity. It is also telling that in the many verses Drake incised onto his vessels (forty are known to survive), there is no mention of his disability. Drake referenced many topics: heterosexual desire, loss and grief, religious faith, systems of commodification, the intended use of his vessels, cross-cultural encounters, and even occasionally his enslaved status—”Dave belongs to Mr. Miles / wher the oven bakes & the pot biles” (July 31, 1840).93 However, Drake never commented on his disability. While this is negative evidence, we believe his omission highlights the constructed nature of Drake’s “Dave” persona.

When seen in this way, Drake’s now-famous signature, “Dave,” becomes a marker not only of his identity as author and maker but also of his effort to declare his skill and independence, despite his enslaved status and disability. As with all enslaved craftspeople, Drake’s interest in asserting his artisanal ability could have been both personally and professionally motivated as well as a means of furthering his enslaver’s profit and thereby maintaining his assigned value. Similar to the ways that scholars have read Drake’s signature (which appears on over a hundred vessels) and his verses as a means of establishing a marketable “logo,” so too might we think of disability gain as inherently shaped by Drake’s multiple layers of enmeshment in the market.94 In this sense, disability gain, which has linguistic roots in accounting practices related to calculations of value, returns us to the uneasy constellation of craft, disability, and race, in which Drake’s persona and his logo enabled his enslavers to gain monetarily from him.95 Viewing disability gain, then, in light of conditions of unfreedom means acknowledging both the way that Drake minimized or omitted the contributions of others in his creation of his amanuensis as well as his logo’s co-option by his enslavers.

In light of what historians have revealed about enslaved disabled people’s use of disability to advance their agency whenever possible, it is also worth considering the potential connections between Drake’s disability gain as a creator and the means through which his disability might have engendered opportunities to shape his lived experience as an enslaved person. Historians have demonstrated that enslaved people used physical and mental impairments to their advantage when they could—to control work assignments and sometimes to reduce the risk of being sold away from family and friends.96 In Drake’s case, scholars have hypothesized that his disability might have kept him from being moved to Louisiana with his then enslaver, Henry Drake, and instead sold to the Landrum family in Edgefield. That stay likely involved a forced separation from Drake’s wife and family. Scholars have linked this trauma to Drake’s inscription from August 16, 1857, “I wonder where is all my relations / Friendship to all—and every nation.”97 In this sense, Drake’s disability together with his skill proved to be a personal liability. Yet perhaps Drake’s collaboration with Simkins might have resulted in a different kind of disability gain for them or for his later coproducers, who might have leveraged their situations to remain together. While we do not know the specifics of Simkins’s enslavement, given his importance to Drake’s production, it is possible that he was sold or leased along with Drake to different white pottery manufacturers. In other words, the collaboration of these enslaved artisans and the spectacular pots that resulted might have provided an incentive for their enslavers to allow them to remain together.

Conjuring Creations

Another possibility for framing Drake’s and Simkins’s social experiences of disability arises when we consider the persistence of African ancestral rituals, traditions, and worldviews in South Carolina’s enslaved African American communities. Decorative arts scholars have long been interested in a group of “face vessels” produced by enslaved and free Black potters in the Edgefield area in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which were also copied by white potters. These enigmatic clay items, which consist of human faces modeled in what appear to be expressions of fear, sadness, and anger, have been linked to Kongo power figures (Nkisi Nkondi) and to enactments of African-derived spiritual practices. Scholars have noted the illegal forced migration and sale of a group of Kikongo captives in the Edgefield region in 1858, positing that this influx might have sparked the creation of face vessels.98 Thus far consideration has been tied to the items themselves in terms of what their function, materials, and style might reveal about African American Edgefield potters’ spiritual beliefs and cultural practices. Instead, we propose taking these artifacts as a point of departure to raise questions about how conceptions of disability generated in West-Central Africa might have shaped the treatment of Drake and Simkins by enslaved communities in Edgefield. As Barclay argues, in some precolonial West African cultures, people who would be perceived as disabled in a Euro-American context were revered as “differently abled bodyminds” in possession of spiritual power and therefore also potential social power. Barclay relates this different view of disability to “conjuring” practices undertaken by enslaved African Diasporic peoples in North America.99

One face vessel in particular may evidence this connection. A piece from about 1850–70 in the collection of the Chipstone Foundation has darkened eyes (fig. 15). Chipstone’s catalogue entry for this object and its interpretation in the current The Dave Project exhibition at the Milwaukee Art Museum highlights this feature as unusual: “More atypical is the glazing of the eyes and the depiction of pupils, possibly using manganese or iron oxide.”100 While the eyes are made of bright white kaolin (the material basis of porcelain), the maker applied a glaze to change their color. The back of the vessel bears an inscription. Early scholarship identified the text as “Squire Pofu.”101 More recent work rereads it as “Squire Pope,” a name that appears in Edgefield census records.102 However, viewing the vessel through a lens of disability history may lend credence back to the former interpretation. Scholars Claudia Arzeno Mooney, April L. Hynes, and Mark M. Newell note that pofu, in present-day Swahili and late nineteenth-century Kikongo, translates to “blind.” They further note that Kikongo words were used in nineteenth-century South Carolina and that many people transported on the illegal slave ship the Wanderer, with whom face vessels are connected, spoke Kikongo. Connecting the inscription to the darkened eyes and its conjuring function, the authors posit that it was used “to either cause or cure blindness.”103 In the deficit model of disability, in which blindness could be used as a weapon, this is believable. And indeed, multiple scholars have written about targets of conjuration who experienced blindness, among other disabilities. However, Barclay’s scholarship presents another option in which the “blind squire” is the conjurer. “Many conjurers,” she writes, “exhibited various forms of physical and sensory difference that linked them to the spiritual realm and reflected their power.” A large portion of these differences were centered around eyes, such as blindness, “light or different colored eyes,” and “red eyes or albinism.” In two of Barclay’s examples, conjurers’ blindness endowed them with “a more penetrative type of ‘vision’ that extended into the spiritual world.”104 To move away from the cause/cure dichotomy of the medical model of disability, blindness may have in fact been the source of the conjuring itself, suggesting a larger possible connection between Edgefield face vessels and disability.

It is important to consider that for enslaved disabled people in Edgefield, disability as a lived experience was entangled with multiple structures of power beyond that of enslavement. There is the possibility of Drake’s and Simkins’s enmeshment in an African American community in which strict binaries of abled/disabled were not sustained and where disability could be a mark of power and possibly an indicator of a ritual practitioner. To that end, it is useful to circle back to the meaning of “thing” that we introduced above. Historian Jason R. Young has called attention to scholars’ use of the critical term “thing” (as opposed to the term “object”) in relation to Edgefield’s face vessels as a means of acknowledging the agency wielded by items, in particular items with spiritual and ritual significance.105 Young’s invocation of the power of things resonates with our attention to the collaborative and multivocal act of creation that brought the disabled Drake and Simkins together. In this alternative view of subject-object interactions in which agency is shared between clay, wheel, and people, we perceive the potential for disability gain to be achieved not only through but also in concert with the power of material things. By shifting our understanding of artifacts from passive evidence to zones of mutual interaction, entanglements of things’ animacy and Black disabled material histories become perceptible as potentially reinforcing. So too the material agency of those enslaved people, whose subjecthood was legally denied, can become evident through artifacts’ vibrant afterlives.106

Drake, Disability and Descendants

Alongside Drake’s verses and signature, the physical size and weight of his coproduced vessels have been recognized as among their defining formal features in scholarship and interpretation. The earliest collectors of Drake’s work noted its scale first and foremost. In early 1919, when the Charleston Museum acquired one of the 1859 pieces inscribed “Dave & Baddler” (see fig. 11), Paul M. Rea, the museum’s director, observed, “Until this jar was received we had no idea that such large pieces of pottery were made in South Carolina.”107 When Rea wrote those words, he did not know about its enslaved joint makers. In the years since, the large scale of Drake’s vessels has become a persistent part of his authorial identity and a factor used to identify vessels as being by him. Yet scale is also a consistent factor in communal production. As art historians Glenn Adamson and Joshua G. Stein argue, large-scale sculpture changes questions of authorship because of the number of people required for its execution.108 Industrial ceramic production similarly always relies on collaborative labor. Disability further upends standard authorship models. This standard model prizes the individual, rather than the collective, including tying the individual’s mark to concerns about authenticity. It is poignant, therefore, that the first Drake piece to be acquired into a museum collection was by Drake and Baddler. As we begin to imagine Drake’s vessels materializing the skills of several people, scale also stands in for their presence in the contemporary world and therefore in the historical archive.

Together, Drake and Simkins help us to consider the stakes of authorship—in the historical context of their creation and today—when a shared choreography from the embodied or tacit knowledge of craft, creativity, and disability come together in artistic practice. Moreover, later joint creations encourage us to look further outward to consider multiple turners as well as networks of enslaved men, women, and children who made the work of Edgefield’s potteries possible. As we turn to the space of the art museum and questions of authorship and value, we want to keep this community in mind.

In April 2023 Pauline Baker, Priscilla Carolina, Daisy Whitner, and John N. Williams Sr., all descendants of Drake, were interviewed by Washington Post reporter Dave Kindy. They spoke of their pride in their ancestor as well as the grief they felt in reading his verses. They also called readers’ attention to the fact that their family does not own any of Drake’s vessels and that the money these pots garner at auction does not benefit descendants of enslaved people in the United States. As Kindy summarizes, “There is little agreement on how to address the fruits of enslaved labor and the profits it has generated. The result is that families like Dave the Potter’s descendants have few options for sharing in the wealth connected to their ancestor’s creations.”109 We honor these descendants’ claims for their long-denied ancestral legacy. At the same time, their call for some form of reparations directs attention to the issues of value and authorship at the heart of our research. In a conversation recorded in Boston at the MFA, descendant Pauline Baker relayed, “It is a good feeling” to learn about her ancestral connection to Drake. Descendant Daisy Whitner concurred, adding that this was especially true “because a lot of Black Americans don’t know anything about their ancestors, absolutely nothing.”110 By considering Simkins as well as Baddler, Mark Jones, and Abram as collaborators with Drake, we envision the possibility of an extended descendant community, one in which the families of multiple comakers and perhaps even Edgefield’s larger community of enslaved workers might similarly recover their legacies.111

In this essay, we have argued for Drake’s cocreated vessels as material participants in the complex entanglements of Blackness, physical impairment, and skill in the nineteenth-century South, where enslaved people negotiated disability despite being denied ownership of their own labor or themselves. As we approach Drake’s unfolding legacy, and the afterlives of slavery in the United States, we are prompted to consider what happens when two disabled makers, together with other coproducers of Drake’s vessels, are collapsed into a model of single authorship. With increasing frequency, questions are being raised about who profits from “Dave,” including by several authors in the Hear Me Now exhibition catalogue.112 What is sacrificed when dealers, curators, scholars, and museumgoers attempt to fit the disabled enslaved potter David Drake into a contemporary art model, wherein value is determined by a work’s ability to be directly tied to a named and well-known individual artist?

Using the now-famous quilts of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, art historian Anna Chave has provided a haunting example of the reductions in artifacts’ multivalent personal and community-held meanings when items crafted by Black makers are forced into white-centric and heteronormative narratives of art history in museum exhibitions.113 As we approach Drake’s vessels, we are similarly drawn to consider what happens when “crip things” with vital ties to enslavement are moved into the art museum. In conclusion, we want to ask what might happen if we centered disability in Drake’s and Simkins’s stories. What if we recognized “Dave” as another type of construction, as a collective? Hear Me Now accomplished vital work by beginning to acknowledge the many makers at Edgefield’s potteries and the importance of “multiple maker(s),” as the exhibition listed the identities of “unknown” makers. We encourage consideration of whether in some instances the “known” maker, “Dave,” was a collective.114

In their 2023 press release announcing the entrance of a Drake vessel into their collection (see fig. 3), the National Gallery of Art (NGA) concluded by summarizing what they identified as the historic importance of this accession: “This is the first work known to be made by an artist while they were enslaved to enter the National Gallery’s collection. It is also the first ceramic vessel to be purchased (rather than donated) for the collection.”115 The NGA statement is indicative of a larger framing of Drake that has crystallized across museums, dealers, and collectors. We recognize the NGA’s efforts to bring more works by African American makers, and enslaved makers specifically, into their collection. Given the fact that the NGA is currently under political attack to cut Diversity/Equity/Inclusion initiatives, we are mindful of the dangers in pushing for institutions to go even further in inclusivity efforts. Yet for us, this statement that invokes Drake’s identity as an enslaved but not a disabled maker encapsulate the missed opportunities of omitting disability from our understandings of Drake’s creativity. As we think about the ongoing hopes of Drake’s descendants, such as a scholarship fund in his memory for African American students, we are eager to see whether attending to Drake’s disability can be another means to enhance a communal recuperative project—one that prioritizes connection and collaboration as a starting point for redress. We hope to inspire others to approach documentary, material, and visual archives attentive to the possibilities of disabled makers and multiple makers, to keep the potential for disability, creativity, and multiplicity in mind, and to speculate carefully about the need to create space for making otherwise.

A later NGA blog post included reflections from contemporary artist Phoenix Savage on the importance of Drake’s fame today in spite of the systems of slavery that worked to erase his identity, saying, “We know him. He made sure of that.”116 Savage’s comments make clear that Drake’s pieces are so special because of how, in inscribing his works, he tied his own longevity to the survival of the stoneware itself—one of the most durable types of clay. Drake’s pots articulate a version of Black futurity that overcame enslavers’ attempts to limit or control Black futures117 Scholars have argued that in our contemporary world, disability, too, is deemed incongruous with futurity.118 Because disability is equated with suffering and dependence, the cultural response has been a long-standing preference for death over disabled life. Disabilities, by ableist definitions today, both curtail futures and simply do not exist in utopian visions of tomorrow. To see Drake’s personhood and history as piercing the present without his disability is a failure to imagine his disability moving with him into the future, just as it is a failure to imagine that many enslaved craftspeople were disabled and that Drake worked with them. To remove disability from Drake interpretation because it requires an embrace of speculation is also to cut off descendants of disability from their ancestors. As Drake’s story continues to gain complexity, we urge those researching and writing histories of him and other historically marginalized artists and craftspeople not to “cure” these figures of their disabilities and thereby deny the impacts that their impairments had on the works that we are left with, beautiful as they are.