Elevated: Along the Fringes of 291 Fifth Avenue

Threshold People

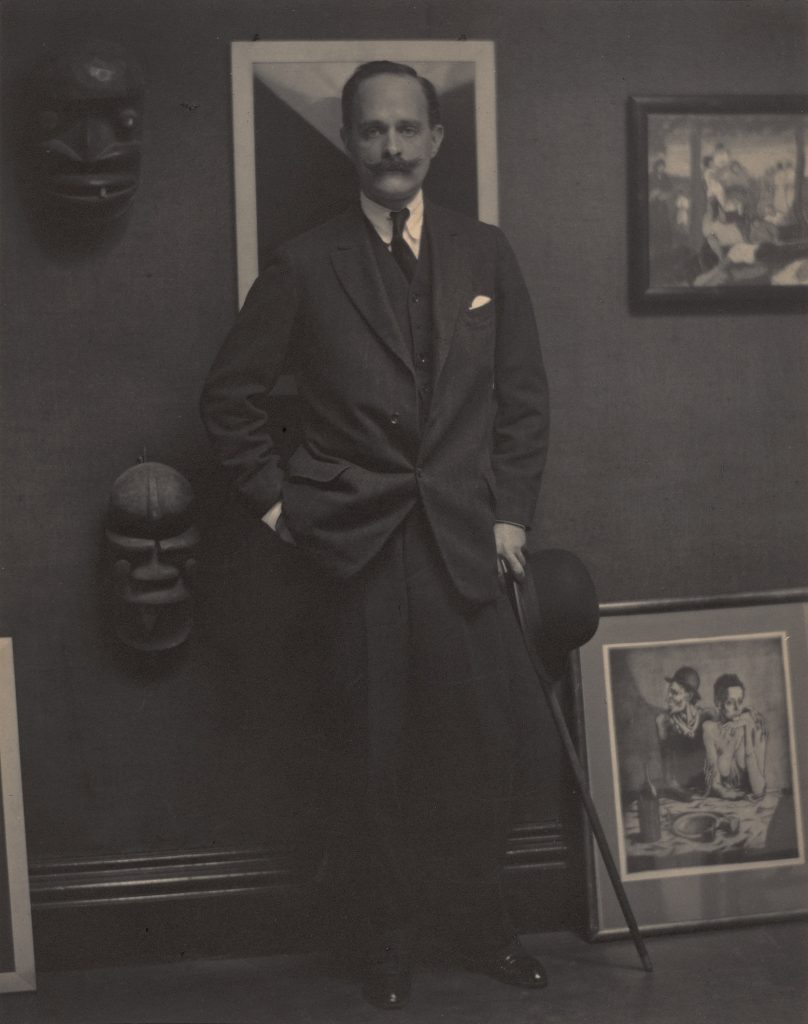

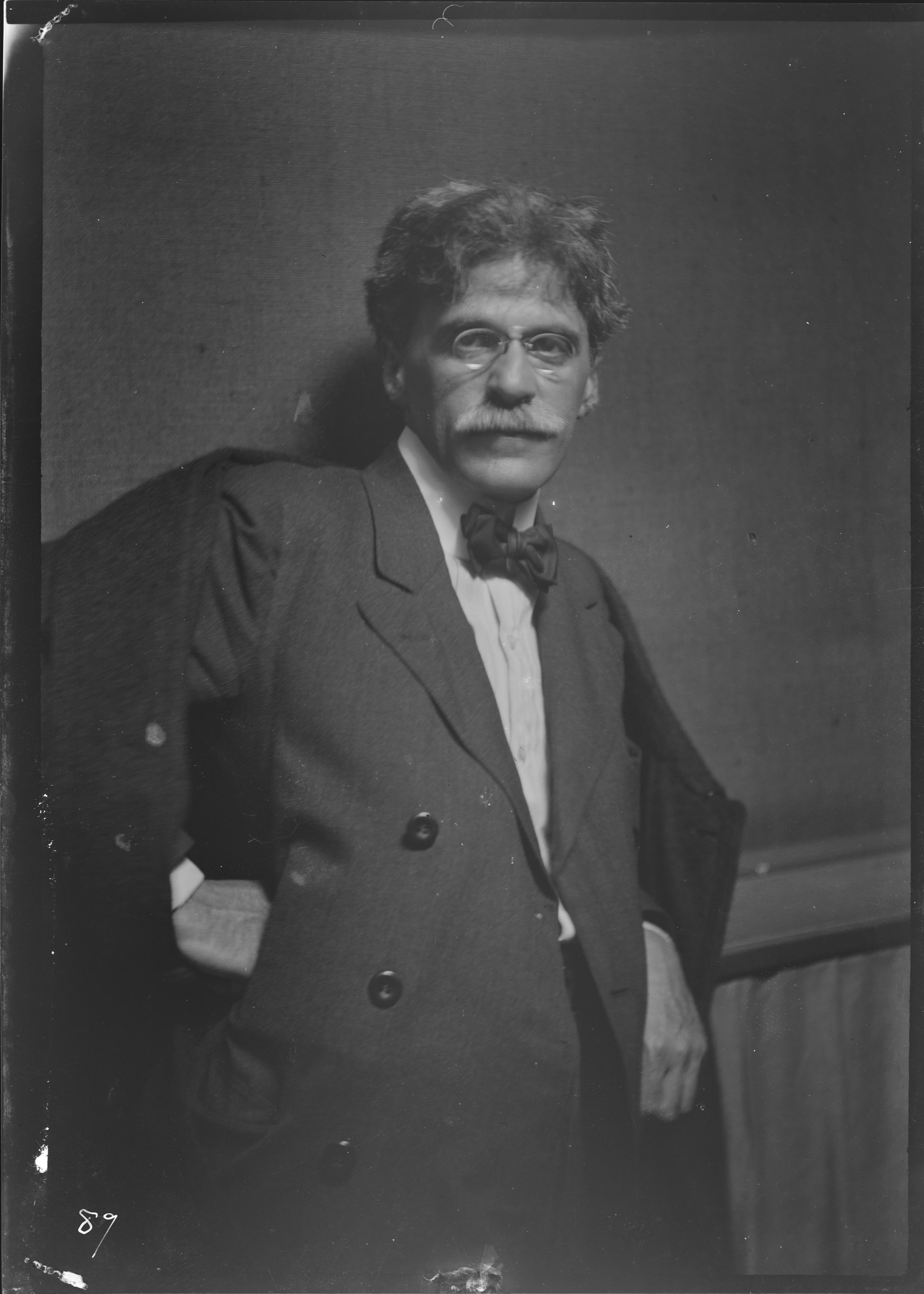

In 1910, the photographer Anne Brigman snapped a portrait of Alfred Stieglitz leaning against a burlap-covered wall of his gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue (fig. 1). His thick eyebrows brush against the wire frames of his glasses, and his graying, unruly tresses tumble toward his ears and cast shadows across his forehead. His elbows, hidden beneath the folds of his overcoat, bend outward as his fingertips curl inward. These are the same hands that, seven years later, framed a photograph of the noted West Indian scholar and historian Hodge Kirnon leaning against a doorframe (fig. 2). In the portrait, the dark skin of Kirnon’s fingertips trace the white fabric of his shirt, and he tugs at his suspenders in a subtle gesture toward the menial job he had taken to support his intellectual and cultural work: to lift viewers from the restless sidewalks of Midtown Manhattan to the attic-level artistic center.

Beneath the flesh of his left hand, a vein splits and pulses, forming a tapered, wedge-shaped ridge that echoes the triangular fold of his collar. The angles of these slanted lines emerge at the bottom of the picture plane, where Kirnon’s knuckle and wrist intersect, and again in the shadowy cleft between the extended index finger and the fist of his other hand. The elevator operator stares directly at the camera, his soft, almond-shaped eyes piercing through the shadows that cascade across his face and into the lens. In this instant, as he locked glances with Stieglitz, as the photographer snapped the shot, these two men met across an entryway and over a threshold—one behind the camera, the other in front.

This study explores the symbolic resonances of the in-between: the fringes of the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, the doorway where Stieglitz and Kirnon met, the elevator suspended between the streetlights and storefronts below and the heights of the artistic center above. In my examination of this passageway, the peripheral space along the fringes of the gallery takes shape, in Mircea Eliade’s words, as the “limit, the boundary, the frontier that distinguishes and opposes two opposite worlds,” as the threshold where two spheres overlap, where one realm ends and another begins.1 I suggest that Kirnon, who traversed these boundaries endlessly as he lifted and lowered passengers, was a “transitional being”; wedged in the border between the mundane realm below and the hallowed halls of the gallery, he learned to navigate social and intellectual borders with deftness and grace.2 In the elevator, he crossed paths with artists—many of them foreigners and outsiders engaged in their own struggle of “getting up,” as the German-born painter Oscar Bluemner once put it, of negotiating the “vertical of American society”—who occasionally invited Kirnon into the inner sanctum of their circle.3 Often, however, they leveled him as he lifted them up through the physical layers of the space, pushing him down in their struggle to hoist themselves up a social hierarchy that was splintered along the lines of gender and race. In recovering Kirnon’s previously forgotten place along the margins of the gallery, my aim is to retrace the complex contours of this ascent by suggesting that the artists who crossed the entryway into the elevator were, like him, navigators of the liminal realm; they, too, to borrow Victor Turner’s phrase, were “threshold people.”4 In this essay, I aim to complicate the existing art-historical literature by tracing the ways that they rose up to become archetypal American modernists from the in-between and out of the fault lines where cultures intersect. I suggest that they were not only invested in elucidating what made American art American—in developing a nativist aesthetic—but also in creating works of art that negotiate the spaces between cultures. My intention, in delving into these edges and fringes, is both to point toward new questions about the artists of the Stieglitz Circle and to unsettle discourses of American modernism that have historically been bounded by national borders and rooted in discourses of national distinctiveness.

This essay, hinging on an understanding of the spatial and symbolic significance of the intimate geography of Stieglitz’s gallery, suggests that the interactions that took shape within the physical boundaries of the small, architecturally humble space open insights into the broader dynamics of cultural discrimination and privilege. Ernst van Alphen, in his discussion of the symbolic resonances of his own home, explores the blurring of the intimate and the cultural within the small spaces of the domestic realm. He suggests that his address, the place where he lives and builds his deepest personal memories, is also a space that is continually “intruded upon” by the expanse of history that surrounds it. In the rooms of his home, he notes, the familiar and the cultural collapse and collide, shaping both the way he “feel[s] at home in that house” and the way he engages with the ruptures of the past.5 This study serves as a useful foundation for an exploration of the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, a site that although not exactly a domestic realm, was a living space before Stieglitz converted it to a gallery.6 It remained, for many of the artists who gathered there, a “place of comfort,” a kind of home.7 The artistic center emerges in my study as a micro-scale cultural space: a microcosm that contains the social tensions of the political sphere, a place where intimate encounters intersected with the unfolding of cultural history.

The address of the gallery, where, as Brigman suggests, the “numerals . . . have grown to mean more than numerals,” had such a profound metaphorical salience that the gallery was often identified by its physical location along Fifth Avenue: 291.8 Indeed, Stieglitz published Brigman’s description of the gallery in a special issue of his journal Camera Work titled “What is 291?” Entirely devoted to the responses that he received after asking his colleagues “what they see in [291]; what it makes them feel,” these pages are filled with essays and poems that transform the space from a humble loft into a symbol for their most elevated intellectual ideals.9 Printed in these pages alongside the writings of prominent artists and intellectuals he lifted up as he worked in the elevator, Kirnon’s contribution to the collection describes the gallery in a way that transcends the boundaries of the physical structure to suggest its figurative reverberations. “It would be sheer impertinence to encourage the idea that words are efficient to convey all that I gleaned from ‘291,’” he writes, noting the limits of language in conveying the depths of its influence on him:

Visitors to “291” will find no difficulty in calling to mind how readily Mr. Stieglitz replies with his usual “I cannot tell you that” in response to some inquisitor who pleadingly entreats him for an explanation of what the paintings mean to him. I fail to see how Mr. Stieglitz could justly claim an adequate reply to this subject, when it is quite apparent that it is through the many exhibitions of these paintings, coupled with an inexplicable something else, which have given the Secession its unparalleled record, and have also rendered its meaning so significant. . . . I have found in “291” a spirit which fosters liberty, defines no methods, never pretends to know, never condemns, but always encourages those who are daring enough to be intrepid.10

In his essay, Kirnon intimates that he was—at least at times, at least partially—welcomed into the center of the gallery. This place, this address, was not only where he lifted others up, where he rose and fell along the length of the elevator shaft, but also a space that engaged him, that pulled him inward, that remolded his ideas and redirected his intellectual work in profound ways. At 291, he learned to engage with elusive truths, intangible and often, as he suggests in his writing, indescribable, with a sense of curiosity and courage.

Stieglitz and Kirnon, who worked together in these rooms above the street that resonated for the elevator operator with an “inexplicable something else,” existed in the ambiguous spaces between systems and structures, sliding through the network of socially constructed categories designed to determine cultural status.11 They remained suspended in the in-between, in the boundaries that divide nations, cultures, and widely accepted racial constructs. Stieglitz, as a second-generation German Jewish immigrant, continued to grasp after, but was never able to reach, the impossible, unattainable ideals of whiteness. He fought throughout his career to hide his ancestral roots out of his longing to elevate himself within the stratified social structure in a culture that never fully embraced him.12 Kirnon, from the edges of the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, was also engaged in a struggle to make sense of his in-betweenness. Because he was a foreigner, a recently arrived immigrant, he too struggled to become an American, to fit into the structures and strictures of blackness in this nation. As “transitional beings,” “threshold people,” they were also what Kirnon describes as “wide-awake-men”: intellectual leaders and advocates of “radical change.”13 They were wide awake in the way they negotiated their complex and conflicting roles along the margins, wide awake in the way they worked to reshape the contours of the cultural realm and the boundaries of what it meant to be an American.

Inside the narrow, cramped walls of the gallery and in the pages of “What is 291?” Kirnon surfaces as this kind of threshold person—wide awake and in-between, both pushed down and pulled inward, often, but not always, relegated to the margins. As he notes in the passage he contributed to the special issue of Camera Work, it was here, in this “place of ascension,” that he crossed paths with other intellectuals who pushed against the “ideals and standards established by conventionalism”; it was here he learned that his work was “worthy in proportion as it [was] the honest expression of [himself].”14

Kirnon’s work, his real work, the work where he articulated his deepest concerns, however, was not the work he did each day as the elevator operator at Stieglitz’s gallery, but instead the work he did as a cultural critic, as a writer and historian. An early supporter of the black intellectual leaders Hubert H. Harrison and Marcus Garvey—both, like him, immigrant scholars from the Anglophone Caribbean—he wrote articles for Negro World, and, in 1920, three years after 291 closed its doors for good, he began to serve as the editor of the short-lived but significant magazine The Promoter. As he toiled along the fringes of a gallery devoted to shifting, controversial, even radical understandings of art, Kirnon was developing ideas about radicalism as a form of social revolution—as a fight for the redistribution of cultural power and privilege. “Racialism and Radicalism . . . might be considered as different varieties of the same kind,” he argues in an essay he circulated in The Promoter, a “bifurcation of the same stem”; they are both outcomes of unrest, of discrimination, of “dissatisfied and discontented peoples seeking some clear solution towards alleviating their present condition.”15 As he worked at 291, a place where he foresaw the “inevitable decline and extermination” of stagnant “institutions,” Kirnon was also rising up among “wide-awake Negroes.”16 He was emerging as a leader in the struggle for a revival of black cultural pride and vibrancy, for a resurgence of creativity.17 As he stood in the doorway of Stieglitz’s gallery, suspended above the street and below the attic, Kirnon could think about the threshold between forced servitude and racial emancipation, about what it meant to be in the midst of “social transformation and reconstruction.” He learned to be “servile and humble” in his daily tasks in the elevator as he began to insist in his writing, for the “right and opportunity to live.”18

As Kirnon suggests in the essays he circulated in The Promoter, he navigated the in-between in many aspects of his life; he was in profound and complex ways a threshold person. He worked to negotiate his divergent roles as an American intellectual who was finding ways, in his words, to “express . . . his manhood” and, at the same time, to exist, often stripped of his masculinity, in the margins—to be what Stieglitz describes in the opening pages of “What is 291?” as a “West Indian Elevator Boy.”19 With these words, Stieglitz rhetorically lowers Kirnon as a means of elevating himself above widespread visions of Jewish men as feeble and effeminate.20 The photographer recast himself as a wise and fatherly mentor to a childlike black laborer. In the pages that follow, however, Kirnon reclaims his manliness by emphasizing his own capacity for intellectual growth. “I well remember how baffled and perplexed I became when I first saw the exhibitions there,” he writes of his initial forays out of the doorway and into the center 291:

I could see nothing inviting or attractive in paintings so devoid of “beauty,” yet judging from the conversations and controversies which were hourly occurrences, I grew convinced that “291” had a potent meaning and a mission which I did not comprehend. . . . I gradually yielded up most of my previous opinions, and now my confusions and perplexities have become pleasant reminiscences.21

With these words, Kirnon intimates that his ideas evolved through his work at 291 as he questioned his preconceptions and began to participate in—or at least to overhear—the discussions that unfolded in the space beyond the elevator. He moved past his initial confusion and into more layered, nuanced understandings of art and beauty. Stressing the transformation of his ideas and the maturation of his capacity for abstract thought, Kirnon subtly distances himself from what the historian Martin Summers describes as the widespread stereotype of black men as “infantile . . . consumers” and realigns himself with a then emerging model of African American and African Caribbean masculinity that was tied, instead, to cultural production.22 In balancing his diametrically opposed positions at the edges of an artistic revolution and an unfolding fight for social change, Kirnon became this kind of man—a creator of ideas, a “leading light . . . of the post–World War I New Negro movement”—from the threshold, from the elevator at 291, from the space between his homeland and his new home. 23

When he arrived in the United States, Kirnon, like many other West Indian immigrants, experienced a loss of status, a distinct drop in prestige, a plunge like the fall he felt each time the elevator lurched into its descent.24 Growing up as part of the social majority in the village of St. Johns in Montserrat, West Indies, where he was born in 1891, he had access to the kind of education that allowed him to flourish intellectually. He lived a life that, until the moment he resettled, was not wholly defined or restricted by his ancestral heritage.25 Kirnon’s struggle to find a place for himself in his new home was complex and layered: as a recently arrived immigrant, he felt the assimilative pressures that surged up around him—a desire for belonging—but as a black man, he understood that to become American was to suffer under the weight of a racial prejudice he had never felt before.26 In some ways, he was able to achieve a higher social standing because he was not native born, because he was not an African American, because, in a certain sense, he did not belong.27 He felt these tensions, these opposing forces that shaped his new life, even from within the confines of the elevator at 291. The job he took there, lifting and lowering the artists who gathered at the gallery, was manual labor, well beneath the intellectual status he had earned in his homeland. It represented the employment discrimination he encountered in his adopted country that pushed him to the margins of society and the fringes of 291.28 However, it was also work that gave him partial access into the exclusive realm of a not-quite-white photographer who, at times, accepted Kirnon into his inner circle, perhaps because, as a foreigner, the elevator operator lived in the in-between.

It is this position, this place of liminality, that Stieglitz evokes in the photograph he took of Kirnon standing in the edges of an entryway. The doors, wrenched open to reveal the wrinkles of his shirt against the doorframe, allude symbolically to what Kirnon describes in an essay he penned for The Promoter as the “doors of opportunity,” at times “closed tightly against him,” at times “placed slightly ajar for him.”29 It was often Stieglitz who turned this figurative knob, both relegating Kirnon to the margins of the elevator and drawing him into the center of artistic debate, both pushing him aside and snapping the sumptuous, sensitive portrait of him—a photograph that, in the words of the cultural critic Paul Rosenfeld, depicts a “negro” who “looks out warmly, faithfully, selflessly”—over the entryway.30 These two culture workers undoubtedly crossed paths in what Rosenfeld alludes to in his text as the “rickety elevator” that lifted him up to the gallery on his way to the garret, along his own journey from the profane realm to what was, in his words, a “house of God.”31

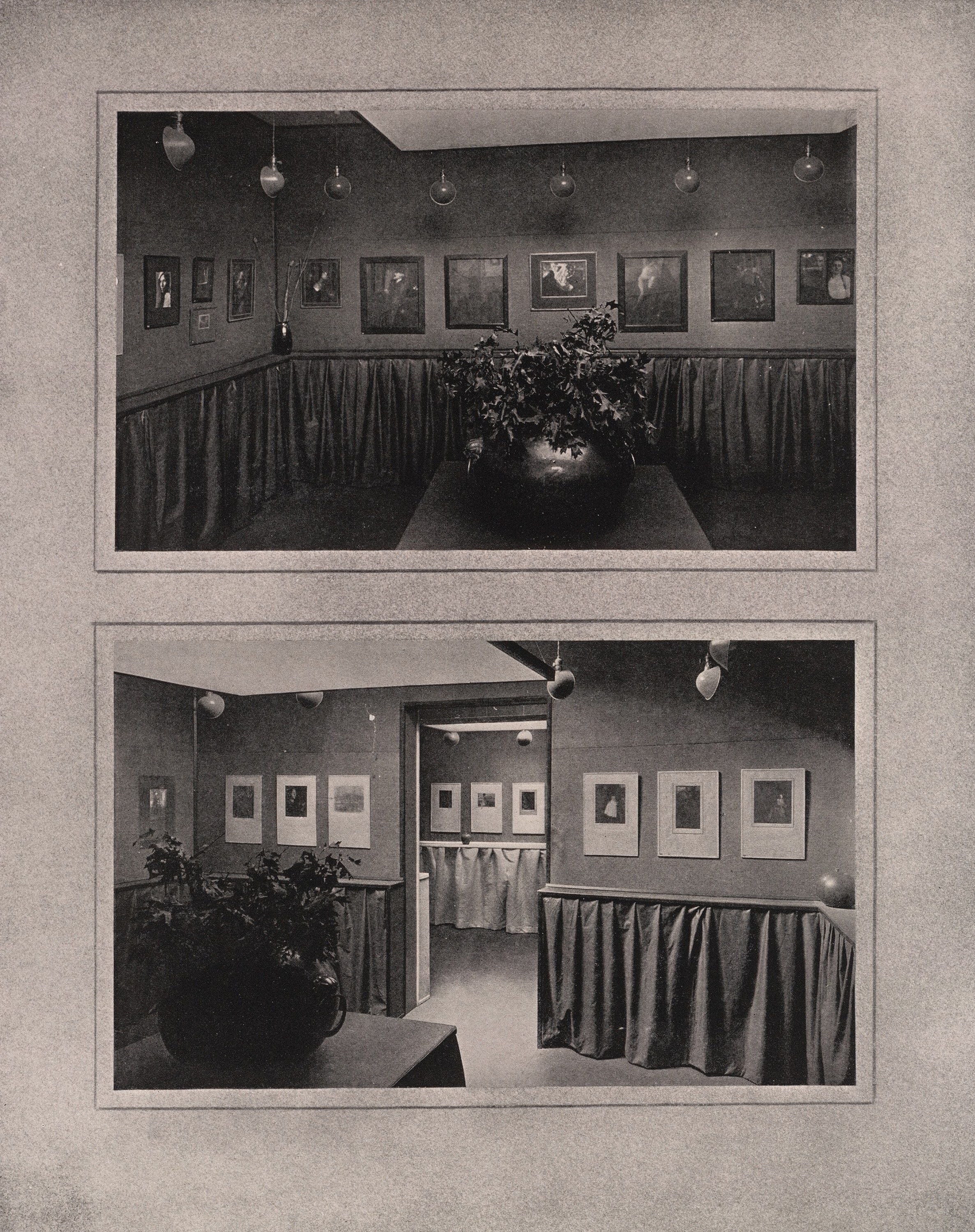

Stieglitz’s gallery, hovering over the mundane streets of New York, represented for Rosenfeld the heights of artistic enlightenment, the soaring pinnacle of intellectual achievement that he discovered after he emerged from the elevator. It was the place where he rose, where he stood in the midst of beauty, where the “spirit of life came alive.”32 The essence of 291 would cohere for him as the traffic swirled below, as he observed the curtains that fell from shelves suspended halfway up the walls inside the gallery. “Alone among the subdued fall of day,” he watched the sunlight—diffused through the semi-transparent scrim and amplified by the row of electric lamps that Stieglitz framed along the upper edge of his installation photographs of 291—shift and pour through the skylight to illuminate the “segments of marble and strange movements of color and line” on display (fig. 3).33 Rosenfeld describes stepping out of the elevator and crossing the threshold to understand what he describes as the “sanctity of these rooms,” a holiness that, in the writings of many of his colleagues, often emerges in connection to the uppermost level of the gallery interior and the light that filtered down from the shimmering heights of 291.34 In his 1906 article “The Photo-Secession Galleries in the Press,” the critic Roland Rood, for example, writes: “I had forgotten that it was evening, and that there must be some kind of light. I had never seen the series of beautiful electric lights that by their quality and disposition gave such a natural illumination that you did not notice them.”35 For Rood, as for Rosenfeld, the carefully aligned modern lamps that Stieglitz hung from the ceiling of 291 filled the rooms with a “mystic feeling.”36

Rosenfeld, who moved through the liminal spaces and across the threshold on his way up to see the light cascading across the walls of 291, was also in many ways a “transitional being.”37 As the son of racially marked German Jewish immigrants, he, like Stieglitz, remained in a state of becoming, of transforming. It was perhaps because of their shared heritage that Rosenfeld made visible what Stieglitz, in his desire for artistic success and cultural inclusion, almost always suppressed: the ambivalence of their position along the fringes, fluctuating, according to widespread racial constructs, between blackness and whiteness.38 Indeed, the overwhelming influx of immigrants that poured into American ports led progressive-era sociologists to create a new regime of racial understanding, one that categorized first- and second-generation European immigrants—who, in earlier decades, would have been understood as white—as genetically inferior racial types. In the years that Stieglitz and Rosenfeld engaged in their intellectual work, they slid between constantly shifting constructs of Jewishness, at times biologically determined and inflexible, but more often culturally based and adaptable.39 Rosenfeld draws these often repressed tensions to the surface in an essay from Port of New York: Essays on Fourteen American Moderns, a book-length study that he wrote in close consultation with Stieglitz. The volume, borne out of the intimacy of their friendship, as the scholar Marcia Brennan notes, took form collaboratively, through a long series of discussions and letters that ultimately shaped Rosenfeld’s words.40 Wanda Corn, in her discussion of the 1924 collection, suggests that as a channel into New York—and synecdochically into the nation as a whole—the symbol of the port surfaces in Rosenfeld’s prose as an emblem of homecoming. In her reading, the image evokes the wave of formerly expatriated artists who were returning from overseas to cultivate what Celeste Connor, in her foundational work on the Stieglitz Circle, terms as a “specifically American aesthetic and social philosophy,” a “native visual idiom.”41 The New York harbor, Corn suggest, emerges in Rosenfeld’s text not only as a metaphor for arrival—for return and reentry, for cultural reintegration—but also as a liminal space, a “place of transition”: a channel between land and water, an edge where nations and cultures intersect.42

Rosenfeld’s imagery of the port filters in a different form into his description of Stieglitz’s work as an artist. Indeed, Rosenfeld frames the photographer’s camera as a threshold between Germany and America, as a kind of passageway from one culture to another, a place where two realms brush up against each other. Through the photographer’s lens, the author writes:

the ancient religiousity of the old world has found channel once again into life; the cathedral upreared itself serene in shrill American day. This is the radiant wonder of the maker of the prints and his tragedy and endless struggle, too: that in flaccid breast-choking, desiccate New York among hard little-feeling people, his spirit should have remained intense, ever-liquid, profoundly poetical, and joyous, outpouring fountainwise in exhaustless flow its living waters. There is the separation of only a generation from the humid European soil to help explain the gift; but that explains really nothing. There are ten student years in green and liberal Berlin and Munich to help; there is a family tree of old life-loving western Jews.43

In Rosenfeld’s text, Stieglitz’s ancestral heritage was what allowed the photographer to reveal in his images an old world as it rises up within the new. It was the fluidity of his Jewishness that created the continual shifting and evolution of his vision. It was the liquidity of his position along the fringes that shaped Stieglitz’s ability to pour life into the withering art scene of what these two wide-awake men understood to be an increasingly mechanistic and industrial metropolis. The Port of New York points toward the possibility that for Stieglitz and Rosenfeld, what it meant to rise up as an American artistic leader was not only to develop a distinctively American modernist aesthetic—but also to skillfully navigate the shifting and unstable realm of the threshold, to create visions that surface from the edges and margins between cultures.

Through the lens of his camera, his channel between here and elsewhere, Stieglitz—perhaps recognizing aspects of his own cultural in-betweenness reflected back at him through Kirnon’s eyes—framed his 1917 portrait of the elevator operator leaning against a doorframe. In that moment, these two ever-liquid “transitional beings”— “American moderns,” to use Rosenfeld’s phrase—stared at each other across an entryway.44 They crossed paths each day in the elevator, a channel, a kind of port leading up to a gallery that, in itself, was a node in a web of intraregional and intercontinental migratory pathways. In the salient words of the painter Emil Zoler, 291, an attic-level space that hovered above the street, was figuratively suspended over the waves that divide nations. “To me—symbolically—‘291’ is the little craft,” he writes in his essay for Stieglitz’s special issue of Camera Work:

the lone speck on the high seas, braving, bleeding, battling and weathering hurricane upon hurricane, single; sailing, creeping and navigating at snail pace; perpetually piloting, crossing, re-crossing, broader channels, to enter, and re-enter anew upon still far greater seas, of far greater importance; eventually destined to arrive at some very positive port; of character, absolute.45

For both Stieglitz and Kirnon, to rise up was in many ways to remain in the transitional spaces of ports and elevators, to weather the liminal edges where spheres overlap, and to cross and re-cross cultural boundaries. From this position along the fringes, Kirnon lifted Stieglitz up to the heights of 291 and metaphorically to the upper echelons of a culture that never fully embraced the photographer because he remained off-white and racially marked. It was from his place in the fringes that Kirnon struggled for social transformation, that he fought for the visibility of those who lived at the threshold, for those who slipped through the cracks of social constructs, for those who remained both rooted and rootless. It was here that he became a loyal and subservient laborer and an intellectual leader—a lowly elevator operator and a significant advocate for social uplift. These two men worked together from the threshold, from the spaces of the in-between, to become American cultural leaders at the same time that they were redefining the boundaries of what it meant to be an American. They were wide awake.

Zig-Zagging Up, Up

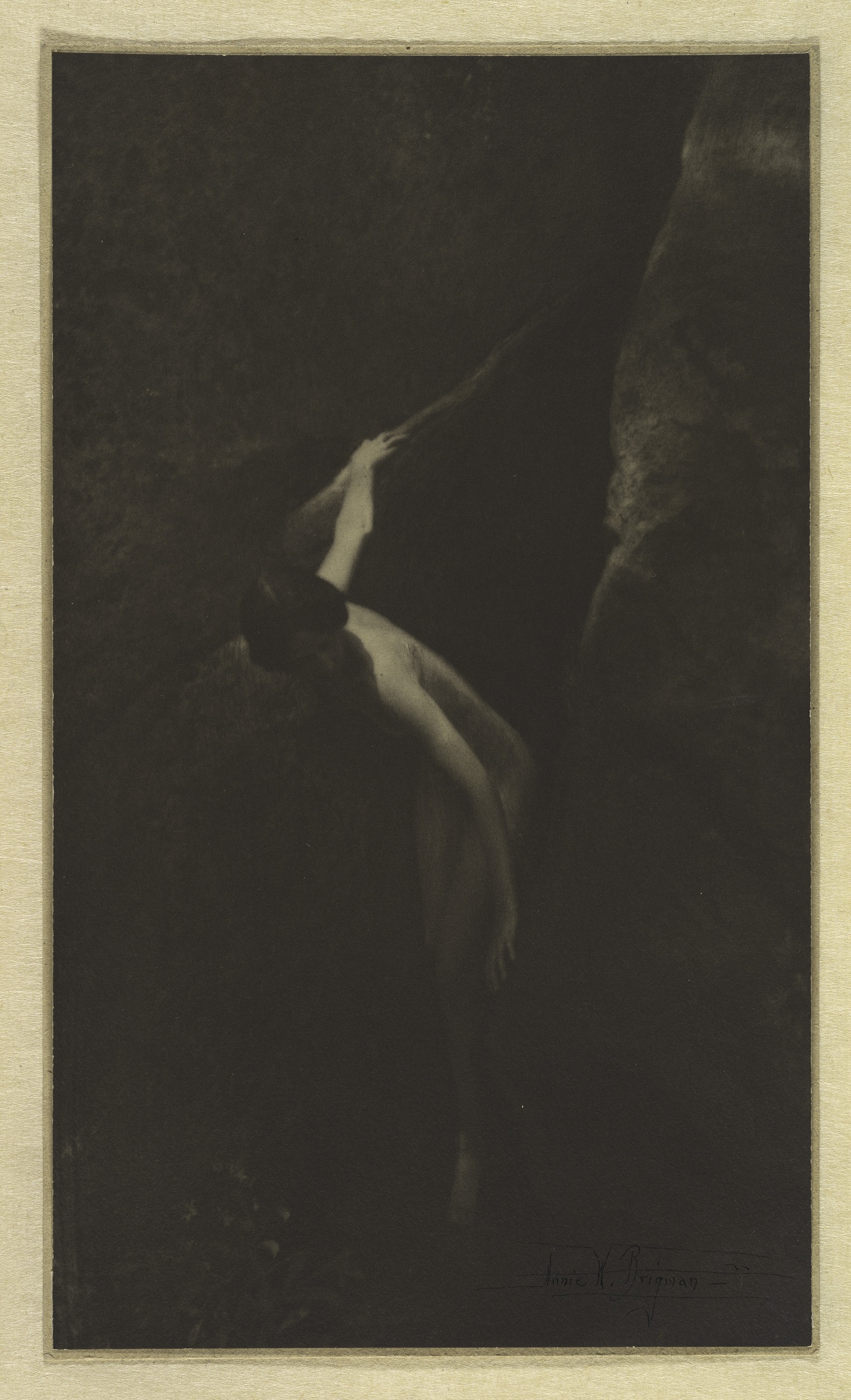

In Anne Brigman’s 1907 photograph The Cleft of the Rock, the form of a woman—possibly the artist herself—surfaces from the blackness of a fracture cut into layers of sediment (fig. 4). Flickers of light bend around her knees, fading into the contours of her shins as they fall into obscurity.46 A subtle, silvery node of sunlight and shadow at the edge of her foot marks the boundary between her pale flesh and the darkness that envelops the rough edges of rock. Her arms extend diagonally from her sundrenched shoulders, weaving across the surface of the fissure in sharp, snaking angles as she pushes herself against the blackness and bends her waist toward the light. Visually, this photograph mirrors the written language that Brigman uses in the essay she penned for “What is 291?” Describing another kind of emergence, another form of twisting and winding, her contribution to Stieglitz’s journal retraces the end of her long-awaited journey from the West Coast to the East, her rise from the restless streets of midtown Manhattan and up to the gallery.

Overwhelmed with fear and struggling to find the courage to navigate the bustling veins of the city, Brigman found what the artist John Weichsel describes as the inconspicuous “sun-disc emblem” that marked the entryway to the gallery, nestled in a humble building with a discontinuous façade, perhaps pieced together from older, remodeled structures.47 Pacing up and down the “long steep trails that lead zig-zag mile after mile,” Brigman discovered the near-hidden entrance—easily overlooked and eclipsed by the surrounding placards for competing businesses—that emerges in a 1917 photograph of the building exterior and continued along her path “away from the trees and brooks, up, up,” into the narrow elevator where she first crossed paths with Kirnon (fig. 5). She rose above the sidewalk, beyond the “heat of the rocks” that were, like the rough wall of stone in her photograph, “blessed by the sun.”48 In the elevator that lifted her into what was for her, as it was for Rosenfeld, the near-sacred realm of the artistic center, she ascended up from the shadows of the mundane and into the glimmering light of artistic awakening. She stepped over the entryway and continued to follow the trail that was unfolding before her. The door of the elevator closed, and she crossed the threshold to behold, in her words, the “Vision—the glory of things beyond,” the gray walls and drop lights of the architecturally humble exhibition space that would alter the course of her career. The “memory and wonder” of that place lingered within her long after she left.49 It stayed with her as she descended back down the levels of the old building. It pulsed within her as the elevator plunged away from the attic and back down to the “lowlands,” drawing her back down to the corner of Thirtieth Street and Fifth Avenue, back down to the rocks cast in sunshine and shade.50

In her description of this journey in her essay for “What is 291?” Brigman lingers on the moment that Kirnon first carried her up from the mundane street and into the hallowed halls of the gallery. “Came a rattle and whirling in the darkest corner, and lo, the elevator about as large as a nickel-plated toast-rack on end with a six-foot African in command”:

“Does this go up to the Little Galleries?” I breasted.

“Yassum!”

A flash of teeth, a tattoo of huge knuckles, a pull on the rope and we were crawling up inch by inch to Mecca.

When I stepped out on the fourth floor. . . . there wasn’t a sound.

I knew the dark brother in the elevator was watching through the grill, and I felt like Brer Rabbit when he was “dat nerbous, dat he kicked out every tahm a weed tickled him.”

The door of the elevator had closed; it was shaking into the third depth.

Ahead was a tiny hall. . . . It was as though I had come from or gone to another planet.51

Brigman, in her description of the elevator operator’s gangly stature and courteous behavior, paints Kirnon, the man who lifted her up, through a complex series of deeply rooted and damaging cultural myths. He emerges in her text as a combined stereotype of a subservient servant and a strapping black laborer; he bears his teeth as a sign of what she perceives to be his animality. It seems that as she wrote this passage, her memory of Kirnon’s dark skin, his black eyes staring at her through the grate, his knuckles wrapped around the rope as he pulled her upward, spurred her move, rhetorically and imaginatively, from the confines of the elevator at 291 Fifth Avenue to the southern plantation—to Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus stories.

Interwoven into her description of the elevator operator, layered with racist statements that flattened who Kirnon was, Brigman’s reference to Harris’s work was, I suggest, thoughtful and carefully constructed. In a letter to Stieglitz from 1914, she describes the process of writing her essay for the issue as another kind of journey, one that led her to textually retrace her physical passage across the streets of Midtown Manhattan and up to the artistic center from many different angles. “I tried a number of times to tell simply and deeply—for your special—our special number of Camera Work, and felt that I’ve failed,” she notes, describing her difficulty in expressing what the gallery meant to her when it “mean[t] so much.”52 The letter, laced with literary references, suggests that her writing process involved many drafts; her reflection on the symbolic dimensions of the gallery was a string of vigilantly selected words that took on many different forms before the version that appeared in Stieglitz’s magazine.

In the final iteration, Brigman alludes to her own anxiety about her passage upward through a reference to a pivotal moment in what became Harris’s 1918 collection Uncle Remus Returns. In her description, she cites almost word for word a line from Harris’s story “How Brother Rabbit Brought Family Trouble on Brother Fox,” part of a longer series of interwoven tales that he first published serially in The Metropolitan Magazine between 1905 and 1906 (fig. 6). The story begins when Brer Rabbit is summoned into King Lion’s lair to help relieve the monarch of a briar caught in his paw. After consulting with the suffering ruler about possible ailments and remedies, Brer Rabbit, on his way home, encounters Brer Fox, who is carrying with him two delicious chickens and a duck. Exploiting Brer Fox’s inability to read, Brer Rabbit recites a forged letter from King Lion, shrewdly pretending that the monarch was outraged by the canine’s absence in the pack that had gathered outside of the ailing lion’s den earlier that day. Brer Rabbit then stealthily follows his associate home after their meeting, arriving at the front door moments after Brer Fox had scurried away to amend his social misstep. With another feigned letter, the sly hare convinces the illiterate Miss Fox to give him her husband’s poultry. Brer Fox returns home from the ruler’s lair to his wife, who, angry about their stolen dinner, lashes out at him about the counterfeit letter he had supposedly written. He struggles to assuage her rage until they pause from their argument long enough to overhear Brer Rabbit’s maniacal laugher ringing out from his own home down the road. Realizing in that moment that the trickster had fooled them out of their scrumptious meal and provoked their marital strife, they vow to seek revenge by hiding in places Brer Rabbit usually passes by and waiting to attack.53

At this point in the story, Brer Rabbit begins to live in constant fear, in a state of heightened alertness; he takes each step with caution, knowing that anywhere he goes, Brer Fox might be waiting to pounce. It is this turning point in the narrative that Brigman quotes in her essay from “What is 291?,” restating Harris’s words in her reflection on feeling, as she lurched up along a thrilling, anxiety-ridden vertical pathway into the unknown, “like Brer Rabbit when he was ‘dat nerbous, dat he kicked out every tahm a weed tickled him.’”54 In the context of the story as Brigman would have encountered it in The Metropolitan Magazine, Harris’s line is repeated as a caption beneath J. M. Condé’s illustration of Brer Rabbit moving cautiously along a pathway bounded by a crooked fence (fig. 7). His limbs—evoking, likely coincidentally, the zig-zagging undulations of the outstretched arms and fingertips in Brigman’s The Cleft of the Rock—are stretched behind him and out into the foreground, as if he is struggling for balance as he teeters at the edge of being caught, as if he is fighting to emerge from the darkness of his deception unscathed.

There are differences between the story Brigman cites and her narrative of her own ascent: as the elevator wobbled upward, she was not bracing herself for a retaliatory response to a devious act; she was not, like Brer Rabbit, a trickster. However, she identifies the nervousness that surged within her as she approached the gallery with his unbearable fear as he anticipates the impending counterattack, rhetorically transforming herself into a tense hare, trembling with apprehension. Significantly, at the end of Harris’s tale, Brer Rabbit ultimately finds a way to move further into the lion’s den and deeper into the center of power by destroying his would-be avenger. Shaking with terror, Brer Rabbit returns to the lair to convince the king that by wrapping his blistered paw in fox hide, the ruler could cure his wound. Literally sacrificing Brer Fox’s skin in order to save his own, Brer Rabbit cuts down his rival in order to lift himself up. Similarly, Brigman, “wilder,” as she stood in the elevator, “than Brer Rabbit,” describes Kirnon in her passage as a lanky, grinning, and animalistic servant. She uses her carefully crafted language to push him down as she alludes to her own moment of rising, both literally, within in the narrow confines of the elevator, and metaphorically, in her work as an artist. Following the pathway that led her up into the fourth-floor gallery, she arrived at the den of the wild-maned photographer whose fingertips, folded against the edges of his hips in the portrait she shot of him in 1910, take on the shape of unfurled claws—of an injured paw (see fig. 1). Although Stieglitz also remained in many ways suspended in the in-between, he was, like the character of King Lion, the leader of the symbolically significant artistic lair he built at 291; he had the leverage to reshape her career.

Brigman’s reference to Harris’s Uncle Remus tales, her textual depiction of Kirnon as a menial laborer who responds to her with an obedient “Yassum,” is based on a string of assumptions about who he was—about his past, his heritage, his position along the fringes of 291.55 Leaning on literary conventions rather than the actual tenor and tremor of his voice, she mimics the contrived dialect that Harris uses throughout his Uncle Remus tales, language that was, during the era, often read as an authentic representation of southern black speech patterns.56 Kirnon, however, was not a former slave who had relocated from the plantation to the city in hopes of forging a path for himself in the wake of unbearable suffering; he was not an African American. He was instead a foreign-born intellectual who resettled in New York in 1908, just one year before he crossed paths with Brigman in the elevator at 291.57 It was here that he earned his living for several years, in the words of the curator and critic Christian Brinton, as the “genial liftman from the southern isles.”58 A respected writer and historian in his homeland, he mingled with artists and “greet[ed]” the visitors to 291 “in mellow monosyllables” as he lifted them up from the restless streets of Midtown Manhattan to Stieglitz’s gallery—and never in the contrived, southern, African American dialect that Brigman evokes in her description of him.59

Brigman, linguistically dismissing Kirnon as a means of rising up into the gallery she describes in “What is 291?” as “Mecca,” frames her own intellect and artistic insight in contrast to what she assumes to be his savagery.60 Forming in her text an unbridgeable distance between them; however, she obscures the striking parallels between their lives: both deeply rooted in humid, island landscapes, both recently arrived strangers to the city, both working along the edges of 291 as they fought to heighten the resonances of their cultural work. Brigman, who was raised on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, links her early artistic development to the wave-beaten shorelines that bounded her childhood. She continued, as the art historian Kathleen Pyne has noted, to explore the wildness of the twisted branches and jagged crests of her second home in California.61 As she stepped off the elevator in New York, feeling as if she had “come from or gone to another planet,” she crossed the threshold into 291 as a kind of interloper. She was a woman among men, a woman from a very different world. She was a woman with a “‘strange, foreign,’” feminine vision that was, for her East Coast colleagues, shaped by her closeness to the earth and the sea—by the untamed coasts from which she emerged.62 Kirnon also remained embedded in the tropical landscape of his native land; as he fought for the “awakening of the race,” for “racial self-realization” in New York, he was also compiling a volume, completed in 1925, that traces the history of Montserrat.63 Although he emerges in Brigman’s text as a subservient stereotype of blackness, he was also in some ways an insider within the intellectual circle that gathered at 291. He remained, like Brigman, always at the edges and in the fringes, never fully excluded from the space, never wholly included.

Kirnon and Brigman, who met in the elevator, the border between the bustling street and the rising heights of the attic, were “threshold people,” “transitional beings”; they were “neither one thing or another,” neither islanders nor city folk, neither insiders nor outsiders.64 They remained on the fringes of 291, in the liminal space of the in-between, in a state of rising up. In the essay she wrote for Camera Work, however, Brigman rhetorically drew upon her position of relative privilege—her whiteness—to cut Kirnon down as a means of pulling herself higher into the exclusive and exclusionary space of 291. She emerged, like the figure in her photograph Cleft of the Rock, out of the wilderness, out of the layers of shadow she cast over him, out of the rhetorical choices she made to level him into a silhouette, out of the way she shaped him into a vision of servility and animality. Winding through what she described as the “long steep trails” that wove “zig-zag mile after mile” through Manhattan, she crossed the threshold into the elevator at 291 and stepped symbolically over Kirnon, “up, up” to the divine realm, “up, up” to the soaring heights of Stieglitz’s gallery.65 To borrow language from the biblical passage she references in the title of the photograph, she found, at the place where she met Kirnon, the shadowy “clefts of the rock,” the “secret places of the stairs”; she moved across what theologians, in their interpretations of the verse, have described as the “zig-zag path” to the “place of ascension.”66 The journey carried her across the doorway into the elevator, a secret and sacred cleft, a nearly-hidden site of spiritual evolution, marked at street level only by “an easily overlooked little wooden signboard with the legend ‘Photo Secession.’”67 Like the figure in her photograph, whose pale fingertips press against the edges of the shadowy rock, Brigman pushed against Kirnon’s blackness in her struggle to transform herself into an artist, to lift herself up—to rise.

Inside (and Out)

In 1913, the year before his groundbreaking and deeply fraught exhibition Statuary in Wood by African Savages—the Root of Modern Art opened at the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, the Mexican-born curator Marius de Zayas posed before Stieglitz’s camera (fig. 8). Leaning against the ruffling curtain that extends along the bottom edge of the wall that marks the otherwise indefinite space as a small, symbolically laden room at 291, he shifts his weight to the left and into the shelf behind him, and his right shoulder lifts in response, partially blocking a work of art he created, on display along the wall. His fingertips curl around the brim of his hat and the top of his cane, in the same gesture of gripping that emerges in the space between the Stieglitz and de Zayas in another image the photographer made two years later (fig. 9).68 In the second photograph, de Zayas stands again in front of one of his own abstract caricatures. Mirroring the position he took for the earlier image, he takes one hand to his hip and holds his cane in the other. Wearing the same black suit and white pocket square, he is flanked on one side by a mask created on the Ivory Coast by the Bete people and on the other by the Paris-based artist Pablo Picasso’s 1904 etching The Frugal Repast. As the art historian Lauren Kroiz has observed, Stieglitz’s portrait of de Zayas frames the caricaturist in the space of the in-between; he is visually positioned along the axis of the image, in the border between socially constructed categories, in the boundaries between what was, in his understanding, the “primitive” and the modern.69 Building on her observation, I suggest that the conceptual foundations of his exhibition Statuary in Wood by African Savages—the Root of Modern Art emerged, at least in part, out of de Zayas’s struggle to situate himself among the intellectual and social elite, to lift himself up, to pull himself from the margins in.70

In Stieglitz’s 1915 photograph, de Zayas, again, holds his cane. He angles it downward in a diagonal toward the floor, emphasizing the connection between the bowler hat he holds in the same hand and the repetition of that form: a second hat, resting on the ridges of the gaunt man’s skull in the Picasso etching propped up at his feet. Visually linked to the man within the frame, de Zayas becomes, in another sense, a subject bound by picture planes. Caught within the edges of the photographic surface, his eyes pierce the lens from within another border, the white boundary of the caricature displayed along the wall behind him. The lines inside the frame, edges where white meets black, slant into the contours of his face, emphasizing the asymmetrical part of his hair. These forms, marks along the surface of an image that he himself created, echo the curving line in the background of Picasso’s work, extending from the upper edge of the etching into the side of the attenuated profile of the subject. In the photograph, it appears that de Zayas also emerges as the maker of the work within the frame behind him and, bounded by its edges, a stand-in for the subject he occludes. He becomes both seer and seen, aligned, in Stieglitz’s image, not only with the haggard man seated at Picasso’s café, but also with the Spanish artist as the creator of each etched mark.

As he developed his research on African art, De Zayas, who emerges within the frame of this image as both vision and visionary, was engaged in a project of remaking the way he was seen, of reconstructing himself as a subject, of untangling the threads of his ancestry that threatened to bind and constrain him after he resettled in New York. Like Picasso, who represented for de Zayas the central pioneering force of a new approach to artmaking and who used the “grotesque and deformed” forms of African art as a platform for transformation, the curator found in his own study of these sculptures a latent potential for a revolutionary recasting of ideas.71 His project, however, took a different turn: it was not focused on the curves of form, but instead on his own precarious position within the complex contours of the social realm. Born in Veracruz in 1888, de Zayas, the son of the noted historian and poet laureate Rafael de Zayas Enriquez, was raised in the upper tiers of Mexico’s wealthy, aristocratic class. Suspended, as the scholars Antonio Saborit and George J. Sanchez have argued, above the “street cries and noise” of the escalating social unrest below, de Zayas remained largely impervious to the struggles of the masses until, at the age of twenty-seven, he was forced to flee his homeland to escape the repressive regime of Porfirio Díaz.72 Although de Zayas benefited from a culture that tended to be primarily stratified along the lines of class instead of race during his formative years, he arrived in the United States to find that his ancestry threatened the status that his affluence and classical education afforded him in Mexico.73 As he crossed the threshold—the border—in 1907 to resettle in New York, he fell from his perch among the Mexican nobility, descending into the edges between nations and the cracks between socially constructed categories. He dropped downward into the liminal realm, becoming, in the words of his colleague Leo Dabo, “racially Spanish, natally Mexican, residentially American, temperamentally universal.”74 The exhibition he developed on African art, inside the elevated, exalted space of 291, became a foundation that he pushed against—as he leans away from the Bete sculpture in the 1915 portrait—in order to gain the leverage and traction that would allow him to rise up out of these ambivalent spaces between cultures and to claim his place among American intellectual leaders.

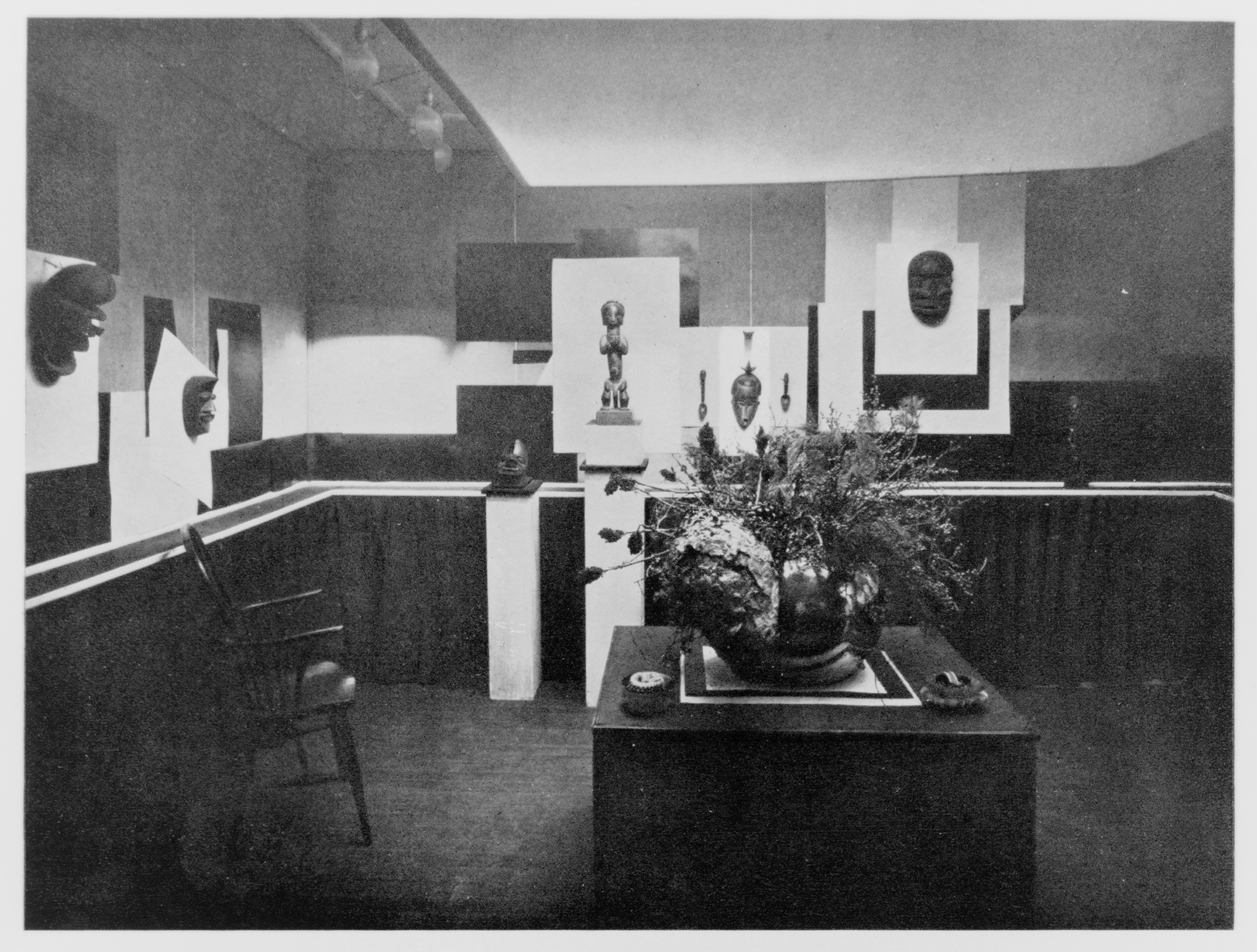

The same mask, suspended on the wall behind de Zayas in Stieglitz’s portrait, also appears, this time in profile, along the left edge of the picture plane of an installation shot that the photographer made one year earlier in that narrow room of 291, at the Statuary in Wood by African Savages—the Root of Modern Art exhibition (fig. 10).75 The dark wooden surface of the Bete sculpture rests against what appears, in the image, to be a sheet of white paper pasted against the fabric-covered wall. The mask is suspended over what de Zayas describes as the “large box” positioned at the center of the small, cramped exhibition space in the “old and decrepit building” at 291 Fifth Avenue, “on which always stood a big bronze bowl full of dry branches and pussy willows.”76 The tonal gradations of the black-and-white photograph masks a revision to the display that the Luxembourgian American photographer Edward Steichen made after the exhibition first opened. In his efforts to “brighten up” the bare walls, he took the carvings down; created geometric designs across the gallery walls using pieces of yellow, orange, and black paper; and rehung them against what he, drawing on problematic atavistic stereotypes, later described as a “background of jungle dreams.”77 In the space of Stieglitz’s attic-height gallery, de Zayas displayed eighteen sculptures that he had acquired during his time in Paris, including a sculpture by the Fang ethnic group of Gabon on a platform at the center of the wall—and the installation photograph—framed to the right by a mask of the Ivory Coast We people. In both its original and reworked form, the exhibition, as the scholar Helen Shannon points out, interweaves the visual balance and decorative quality that typified colonial exhibition traditions and the modernist aesthetic that was taking shape at 291, erasing, or in some cases, suggesting only by accident and coincidence, the ritual functions and cultural meanings embedded in the works.78

In consultation with his colleagues, de Zayas ordered and arranged these forms in a way that diverged from the grid-like, linear, and ordered installations that typified strategies of display at 291 (see, for example, fig. 3). Mounting the sculptures in a way that heightened what he perceived to be their emotive and intuitive qualities, de Zayas suspended them at different heights along the wall, spaced them unevenly, and accented them with bursts of bright color. Even as the sculptures undulated poetically across the gallery walls, visitors encountered them in the spatial center of what the curator understood to be art that “opened its doors wide to science,” art that “ceased to be merely emotional in order to become intellectual.”79 Indeed, for the curator, Stieglitz’s gallery was a place of inquiry and reasoning, “not an Idea or an Ideal,” as he notes in “What is 291?,” “but something more potent, a Fact.”80 Many contributors to the special issue of Camera Work echo de Zayas’s rhetoric, evoking the austere precision of a research facility in their descriptions of the stripped-down, stark walls of the gallery, covered in matte, gray burlap. The journalist Hutchins Hapgood, for instance, describes the gallery as a “‘a laboratory . . . a place where people may exchange ideas and feelings, where artists can present and try out their experiments.”81 Similarly, the writer Paul Haviland frames 291 as a “modern . . . laboratory where human beings as well as their productions may be mere subjects for experiment and analysis, and where investigators of life can find the richest material at their disposition.”82 For the painter Arthur B. Carles and the art critic Christian Brinton, the gallery was a “diagnostic” “laboratory,” where artists gathered to share ideas, or to “test and prove each other.”83 In these writings, the gallery emerges as a space where intellectuals met, as the sunlight fell from the skylight cut in the ceiling, to bring what de Zayas describes as “scientific significance” to the African forms displayed along the plain, unornamented walls. It was a place where they developed “new canons, new theories, [and] new schools . . . from their structures,” where they experimented with ideas, where they awoke to new artistic possibilities.84

The scientific rhetoric that de Zayas evokes in his essay “What is 291?” was also central to his conception of the exhibition he designed for this conceptual laboratory; he used sociologically inflected language to build the theoretical foundation of what he claimed to be the first exhibition anywhere that framed African sculptures as works of art rather than ethnographic curiosities. Hinging on an unquestioned assumption that the work of black artists is unchanging and visually indistinguishable across centuries and continents, the curatorial understanding of African art, as he outlines it in an essay he wrote for a 1913 issue of Camera Work, is based on an understanding that the “representation of Form expresses the state of the intellectual development of each race,” “irrespective of the country and the surroundings.”85 “The Negro,” as he writes in his 1916 book African Negro Art: Its Influence on Modern Art, is “indifferent to the social happenings”; “he has no history,” no capacity for evolution or transformation; his “psychology everywhere remains the same.”86 His “awakened intelligences” are tempered by “savage sentiments,” and his emotional, sensorial approach to form, indicating, in the view of de Zayas, what was his elementary and stunted cognitive development, allowed him to create interwoven concave and convex planes shaped “more in direct relation to [his] feelings than that of higher art.”87

The sculpture that de Zayas explores in these writings was displayed, in a literal sense, higher, above the street, in a place where he found an intellectual refuge. Inside the walls of 291, de Zayas— a recent immigrant who left his home in Mexico just six years before the exhibition opened—found a way to claim his place as a wide-awake man, an experimenter in his new homeland’s central laboratory of ideas. As he visually aligns himself with the Spanish-born artist Picasso in Stieglitz’s 1915 portrait, gesturing by extension toward his own Spanish lineage, de Zayas subtly enacts what the historian Héctor Calderón frames as a widespread strategy for Mexican-born settlers struggling to climb the stratified social hierarchy in the United States. Exploiting the myths of a history constructed by conquerors, de Zayas worked to fashion himself as a descendant of the conquistadors, of the professed heroic warriors of the past who bravely tamed the wilderness and forged a civilization. He stressed his Spanish heritage as a means of placing himself within a legacy of cultural exploration and expansion—of reclaiming the social privilege he lost as he crossed the border and resettled in New York.88 I suggest that for de Zayas, his exhibition of African art became this kind of platform: the project allowed him to reassert his power by engaging an intellectually and linguistically violent conquest, a metaphorical bloodshed. He reclaimed his intellectual prowess through a rhetorical domination of a culture that he believed was marked by savagery and cognitive deficiency; he elevated himself by brutally cutting others down.

From the fringes, from his place in the elevator, Kirnon watched Statuary in Wood by African Savages—the Root of Modern Art take shape as he ushered de Zayas up along the physical contours of this upward and inward ascent. Wrestling with the complexity of the de Zayas exhibition from the elevator and the entryway, Kirnon developed the ideas that he finally published six years later in a 1920 issue of his journal The Promoter. In his essay, “The Growing Recognition of Negro Culture,” he frames Stieglitz and de Zayas as two “American pioneers in what is known as the modern art movement” who broke with the previous tradition of framing “Negro sculpture . . . merely as curios—as the antics of undeveloped, simple and primitive peoples with crude, fantastic and grotesque conceptions of ideals of the beautiful.”89 In “the biggest and truest sense of the term,” Statuary in Wood by African Savages—the Root of Modern Art pried open a new approach to understanding and engaging with these works for Kirnon: they were, in his understanding, transformed through de Zayas’s curatorial efforts into objects of beauty, of cultural and aesthetic value, embedded with “expressions of the impressions and feelings” that had the potential to open new directions in modern art.90 Kirnon suggests that the exhibition was an especially important achievement because it began to open the door for what he describes as the “serious and intelligent consideration” of black history and culture.91 He ends his essay by arguing for the importance of “unbiased and scientific study,” for the gathering of facts that would provide “convincing evidences that the Negro and Africa gave to the world some splendid gifts of culture to which our present civilization is greatly indebted.”92

Kirnon seems willful, even strategic, in his refusal to discuss the problematic theoretical foundations of de Zayas’s approach to African sculpture in this essay. Reveling instead in what the art historian Sarah Greenough describes as the most successful aspects of the exhibition—its efforts to break open deeply ingrained traditions of naturalism with a different visual tradition, tied to sensation rather than sight—Kirnon overlooks the biased language in de Zayas’s writings that in many ways follows the same patterns that he observes in the most destructive approaches to the study African cultures.93 Kirnon was almost certainly aware of the notions of racial evolution that formed the theoretical paradigm undergirding the exhibition at 291. As a man who both worked on the margins of the artistic circle who gathered at Stieglitz’s gallery and fought alongside black intellectual leaders, he was deeply invested in the politics of race and representation. Furthermore, as he notes in the letters he wrote to Stieglitz, he was a close follower of the discussions that were unfolding in and around 291.94 In a 1924 letter that he wrote to the photographer, years after the doors of the gallery had closed, Kirnon remarks that he often turns to the special issue of Camera Work devoted to 291 because it brought him relief during difficult times.95 As he flipped back through these pages later in his career, as he continued his work—his real work, beyond the narrow boundaries of the elevator—he would have lingered on the ways he felt included in that space, reading over his own description of the gallery, his own words as they appeared in Stieglitz’s journal. He would have also inevitably stumbled onto Brigman’s essay, printed on the following page, to find himself distorted into the form of a gangly, animalistic laborer—to find himself pushed down and stepped over as he lifted her up.96

For Kirnon, the in-betweenness of his position, the complexity of the liminal space he carved out at the edges of the gallery, shaped in many ways the rhetorical choices he made as he wrote his essay on Statuary in Wood by African Savages—the Root of Modern Art. Published not in Camera Work alongside numerous other reviews—both positive and negative—of the exhibition, but rather in a journal aligned with the New Negro movement, his words seem to indicate an awareness of his precarious position at the edges of 291. He knew how he could rise up in the eyes of the intellectuals he greeted each day in the elevator and how, even more easily, he could descend from a respected member of the circle to the depths of what they at times perceived to be his savagery. The words he chose for his review of de Zayas’ exhibition, dispassionate and scientific, stripped of the rage that must have risen up within him as he read the curator’s prejudiced treatises on racial evolution, I suggest, became a means of underlining his own cerebral dexterity. Writing without emotion, but instead with a detached intellectuality, he distances himself from the very constructs of black masculinity at the core of de Zayas’s approach to African art. Kirnon, in his essay, instead balances himself on a precarious edge: pushing against de Zayas’s antiblack rhetoric without identifying it directly, fighting for black emancipation without sliding into the very negative constructs of blackness he subtly struggles to dismantle. Refusing to allow himself to rhetorically fall—to become not a man, an intellectual, but instead a myth of impulsivity, emotion, and cognitive deficiency—he found a way in and up, a way to bridge the developing conversations about African art that were taking shape at 291 and also beginning, in a very different form, to surface among black artists and intellectuals in Harlem.

Uptown, discussions centering on the political potential of African sculpture converged in the writings of the philosopher Alain Locke, whose essay “A Note on African Art” appeared in 1924 alongside a piece by Paul Guillaume—a Paris-based dealer who assisted de Zayas in acquiring the collection for the exhibition at 291—in Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life. Although Locke never mentions Statuary in Wood by African Savages—the Root of Modern Art directly, he does attack the theoretical paradigm at the core of the exhibition. Drawing upon language that echoes, but undercuts, de Zayas’s writings, Locke argues that the “theory of evolution” that shaped the curator’s work “has put art into a scientific straight jacket,” limiting the meaning of African sculpture and forcing it to fit within the boundaries of “rigid preconceptions.”97 Locke goes on to suggest that given how these forms have infused European art with new force—allowing artists like Picasso to break open previouslyprescribed laws of representation and move in unprecedented directions—there was an issue that was becoming increasingly pressing for black intellectuals: “what artistic and cultural effect it can or will it have on the life of the American Negro.” “[W]e must believe that there still slumbers in the blood something which once stirred will react with particular emotional intensity toward it,” he continues, claiming that although the artists of Harlem were absorbing an understanding of African form shaped by white artists, curators, and critics, “[n]othing is more galvanizing than a sense of a cultural past.”98 In Locke’s view, the artists of Harlem could—and should—make work that revealed a visual affinity with African art as a means of claiming a place in American cultural and intellectual life, of inserting themselves into a broader conversation about modern art while, at the same time, recovering a sense of pride in their heritage and their pasts.99

Locke, an American-born scholar who wrote from the cultural center of Harlem, made arguments about African art that Kirnon, who stood each day in the elevator of 291, lifting and lowering patrons between the street and the fourth floor attic, never could. Standing in the doorway, at the threshold, Kirnon was involved in an endless project of navigating the spaces between the West Indies and the United States, between Midtown and Uptown Manhattan, between discussions of American modernism and the New Negro movement, between the outside and the inside. His intellectual work unfolded along the axes amid worlds, and he spent his career in a state of rising up, balancing within the complexities of these borders, these edges, with a mastery that allowed him to sustain a place within the dark richness of the liminal realm. It was here, along the margins, that he played a significant role in lifting a circle of intellectuals, many of them threshold people in their own ways—outsiders searching for a way in—up along their complex pathways of social and artistic ascent.

Cite this article: Tara Kohn, “Elevated: Along the Fringes of 291 Fifth Avenue” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 2 (Fall 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1657.

PDF: Kohn, Elevated

Notes

- Mircea Eliade and Willard R. Trask, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion; {The Groundbreaking Work by One of the Greatest Authorities on Myth, Symbol, and Ritual}, A Harvest Book (San Diego: Harcourt, 1987), 25. ↵

- Victor W. Turner, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, The Lewis Henry Morgan Lectures 1966 (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1995), 95. ↵

- This language comes from Bluemner’s discussion of what it meant for him, as an immigrant, to begin at the “bottom of the great American melting pot” and work his way to the “so-called top.” Significantly, his comments emerge within his broader discussion of the symbolic and spatial significance of Stieglitz’s Fifth Avenue gallery. See Oscar Bluemner, “Observations in Black and White,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 51. ↵

- Turner, The Ritual Process, 95. ↵

- Ernst van Alphen, Caught by History: Holocaust Effects in Contemporary Art, Literature, and Theory (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997), 193–204. ↵

- Kathleen A. Pyne, Modernism and the Feminine Voice: O’Keeffe and the Women of the Stieglitz Circle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 98, 68. ↵

- John Marin, “I Know a Place,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 74. ↵

- Anne Brigman, “What 291 Means to Me,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 17. ↵

- Alfred Stieglitz, “Editor’s Note,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 3. ↵

- Hodge Kirnon, “What 291 Means to Me,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 16. ↵

- Kirnon, “What 291 Means to Me,”16; and Turner, The Ritual Process, 95, ↵

- For more on Stieglitz’s Jewish heritage, see Lauren Kroiz, Creative Composites: Modernism, Race, and the Stieglitz Circle, The Phillips Book Prize Series 4 (Berkeley: University of California Press with The Phillips Collection, 2012); Jason Francisco and Elizabeth Anne McCauley, The Steerage and Alfred Stieglitz, Defining Moments in American Photography, Vol. 4 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012); Tara Kohn, “An Eternal Flame: Alfred Stieglitz on New York’s Lower East Side,” American Art 30, no. 3 (September 1, 2016): 112–29. ↵

- Turner, The Ritual Process, 97; Kirnon, “The New Negro and His Will to Manhood and Achievement,” 6. ↵

- Watchman Nee, The Song of Songs (Anaheim, CA: Living Stream Ministry, 1995), 38; and Kirnon, “What 291 Means to Me,” 16. ↵

- Hodge Kirnon, “Racialism and Radicalism,” The Promoter 3, no. 1 (July 1920): 4. ↵

- Kirnon, “What 291 Means to Me,” 16, And Hodge Kirnon, “The New Negro and His Will to Manhood and Achievement,” The Promoter 1, no. 4 (August 1920): 6. ↵

- Kirnon, “The New Negro and His Will to Manhood and Achievement,” 6. ↵

- Kirnon, 5. ↵

- Kirnon, 5; and Stieglitz, “Editor’s Note,” 5. ↵

- For more on cultural stereotypes that position of Jewish men as effeminate, see Karen Brodkin, How Jews Became White Folks and What That Says about Race in America (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998) and Sander L. Gilman, The Jew’s Body (New York: Routledge, 1991). ↵

- Kirnon, “What 291 Means to Me,” 16. ↵

- Martin Anthony Summers, Manliness and Its Discontents: The Black Middle Class and the Transformation of Masculinity, 1900–1930, Gender and American Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 241. ↵

- Marcus Garvey, with Mariela Haro Rodriguez, Anthony Yuen, and Robert A. Hill, eds., The Marcus Garvey and United Negro Improvement Association Papers, Volume XII The Caribbean Diaspora, 1920–1921. What was, in the 1920s, widely known as the New Negro Movement is now often referred to the Harlem Renaissance. I have chosen here to use period-specific language in referring to this social movement. ↵

- Louis J. Parascandola, ed., “Look for Me All around You”: Anglophone Caribbean Immigrants in the Harlem Renaissance, African American Life Series (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2005), 14. ↵

- Parascandola, 4–5. ↵

- Parascandola, 5. ↵

- Parascandola, 5–7, 34. As Parascondola points out, the intermingling of native-born and foreign-born blacks in Harlem evolved into antagonistic conflicts, and social and political alliances between these two groups remained tense as the intellectual foundations of the Harlem Renaissance took shape. Caribbean New Yorkers were often pushed to the edges of what it meant to be black in America and viewed, because of their position of relative privilege in their homeland, as arrogant and condescending outsiders. At the same time, so-called white Americans (or, in the case of this study, immigrants who adopted the lessons of white supremacy as a means of rising up the social hierarchy) tended to accept West Indian immigrants more readily than they did African Americans. ↵

- Parascandola, 8. Hubert Harrison, the West Indian American intellectual leader who influenced Kirnon’s writings, also worked for a time as an elevator operator. Indeed, this was an occupation that many educated and skilled black immigrant intellectuals were forced to take on when they arrived in New York. Also see Jeffrey Babcock Perry, Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883–1918 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 54, 227. ↵

- Kirnon, “Racialism and Radicalism,” 5. Rosenfeld’s description of Stieglitz’s portrait at the entryway to 291 was one that Kirnon himself, as he noted in a letter to the photographer in 1924, would have known; he encountered it among the passages about 291 he read in Paul Rosenfeld’s influential book, Port of New York: Essays on Fourteen American Moderns (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1961). Letter from Kirnon to Stieglitz, May 9, 1924. YCAL MSS 85, box 28, Stieglitz Papers, Beinecke Library, Yale University, New Haven (hereafter cited as Stieglitz Papers). ↵

- Rosenfeld, Port of New York: Essays on Fourteen American Moderns, 273. ↵

- Rosenfeld, 258–59. ↵

- Rosenfeld, 257. ↵

- Stieglitz framed these installation shots during the exhibition season of 1906, at the Edward Steichen exhibition (top) and the Gertrude Käsebier and Clarence H. White exhibition (bottom). The photographs appeared as half-tone reproductions in the April 1906 issue of Camera Work. ↵

- Rosenfeld, Port of New York, 258–59. ↵

- Roland Rood, “The Photo-Secession Galleries and the Press,” Camera Work 14 (1906): 36. ↵

- William Zorach, “291,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 38. ↵

- Victor W. Turner, The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967), 97. ↵

- David R. Roediger, Working toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White: The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs (New York: Basic Books, 2005), 13–18. ↵

- For more on this, see Werner Sollors, Beyond Ethnicity: Consent and Descent in American Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986); Brodkin, How Jews Became White Folks; Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998); and Roediger, Working toward Whiteness. ↵

- Marcia Brennan, Painting Gender, Constructing Theory: The Alfred Stieglitz Circle and American Formalist Aesthetics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001), 89–91. ↵

- Wanda M. Corn, The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915–1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 12; Celeste Connor, Democratic Visions: Art and Theory of the Stieglitz Circle, 1924–1934 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 1–2. ↵

- Corn, The Great American Thing, 5. ↵

- Rosenfeld, Port of New York, 240. ↵

- Turner, The Forest of Symbols, 97. ↵

- E. Zoler, “291,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 41. ↵

- Brigman used herself, her sister, and a friend interchangeably as models in her work, and it is often difficult to tell them apart in her photographs. It is possible that The Cleft of the Rock is a self-portrait, but it could also be an image of one of her close companions. For more on this, see Pyne, Modernism and the Feminine Voice, 98. ↵

- John Weichsel, “291,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 70. ↵

- Brigman, “What 291 Means to Me,” 20. ↵

- Brigman, 20. ↵

- Brigman, 20. ↵

- Brigman, 17. ↵

- Letter from Brigman to Stieglitz, September 12, 1914. YCAL MSS 85, Box 8, Stieglitz Papers. ↵

- After they appeared serially in The Metropolitan Magazine, these stories were collected and published together in the 1918 volume by Joel Chandler Harris, Uncle Remus Returns. ↵

- Joel Chandler Harris, “How Brer Rabbit Brought Family Trouble on Brer Fox,” The Metropolitan Magazine 24 (April 1906): 463; Brigman, “What 291 Means to Me,” 17. ↵

- Brigman, 17. ↵

- For further discussion of dialect in Joel Chandler Harris’s work, see Lee Pederson, “Language in the Uncle Remus Tales,” Modern Philology 82, no. 3 (February 1985): 292–98. ↵

- Howard A. Fergus, Gallery Montserrat: Some Prominent People in Our History (Cave Hill, Barbados: Canoe Press, 1996), 96–97. ↵

- Christian Brinton, “Multum in Parvo,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 45. ↵

- Brinton, “Multum in Parvo,” 45. ↵

- Brigman, “What 291 Means to Me,” 17. ↵

- Pyne, Modernism and the Feminine Voice, 64–68, 92. ↵

- Brigman, “What 291 Means to Me,” 18; Therese Thau Heyman, Anne Brigman: Pictorial Photographer/Pagan/Member of the Photo-Secession (Oakland, CA: The Oakland Museum, 1974), 6. ↵

- Kirnon, “The New Negro and His Will to Manhood and Achievement,” 6. ↵

- Turner, The Ritual Process, 110; Turner, The Forest of Symbols, 97. ↵

- Brigman, “What 291 Means to Me,” 20. ↵

- “Song of Solomon 2,” Barnes’ Notes on the Bible, accessed September 17, 2017, http://biblehub.com/commentaries/barnes/songs/2.htm; Nee, The Song of Songs, 38. ↵

- “291: The Mecca and the Mystery of Art in a Fifth Avenue Attic,” The Sun, October 24, 1915, 5. ↵

- This photograph, according to the art historian Sarah Greenough, was likely taken at de Zayas’s Modern Gallery. The caricature that de Zayas occludes within the image depicts the painter Katherine Rhodes, and the photograph on the left of the image has yet to be identified. For more on this, see Sarah Greenough, ed., Alfred Stieglitz: The Key Set: The Alfred Stieglitz Collection of Photographs (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art in association with Harry N. Abrams, 2002), 252. ↵

- Kroiz, Creative Composites, 55. ↵

- I draw here on David Roediger, who argues that newly arrived foreigners often strategically absorbed the lessons of white supremacy as a means of evading marginalization in the United States. See David R. Roediger, Working toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White: The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs (New York: Basic Books, 2005), 72, 119. ↵

- The connection de Zayas felt to Picasso may have extended beyond their shared artistic and intellectual interests; the caricaturist also likely identified with the critical reactions that the painter garnered by American critics. Picasso often emerged in the press as an “olive skinned . . . Spanish type,” his work cast in terms that would have resonated with de Zayas, as a newly arrived foreigner who left his homeland—and his position of social privilege—in Mexico to slide between the fractured, indefinite, shifting racial constructs that shaped the social hierarchy of his new home. Marius de Zayas, How, When, and Why Modern Art Came to New York, rev. ed., ed. Frances M. Naumann (1940; repr., Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), 31; Kroiz, Creative Composites, 61–62. ↵

- Antonio Saborit, “Marius de Zayas: Transatlantic Visionary of Modern Art,” in Nexus New York: Latin/American Artists in the Modern Metropolis (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with El Museo del Barrio, 2009), 86; de Zayas, How, When, and Why Modern Art Came to New York, viii; Kroiz, Creative Composites, 50; George J. Sanchez, Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 29. ↵

- The Mexican Revolution, as George J. Sanchez points out, began to upend these previous structures of cultural power in the years after de Zayas left Mexico to resettle in New York. See Sanchez, Becoming Mexican American, 20. ↵

- de Zayas, How, When, and Why Modern Art Came to New York, x; Leon Dabo, “Marius de Zayas: A Master of Ironical Caricature,” Current Literature 44, no. 3 (March 1908): 281, as quoted in Kroiz, Creative Composites, 207n7. ↵

- de Zayas, How, When, and Why Modern Art Came to New York, 55. ↵

- de Zayas, 2. ↵

- As quoted in Helen M. Shannon, “African Art, 1914: The Root of Modern Art,” in Modern Art and America: Alfred Stieglitz and His New York Galleries (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2000), 174. ↵

- Shannon, “African Art, 1914: The Root of Modern Art,” 76. ↵

- Sarah Greenough, “Alfred Stieglitz, Rebellious Midwife to a Thousand Ideas,” in Alfred Stieglitz and His New York Galleries (Washington, DC: The National Gallery of Art, 2000), 50; Shannon, “African Art, 1914: The Root of Modern Art,” 169. ↵

- Marius de Zayas, “291,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 73. ↵

- Hutchins Hapgood, “What 291 Is to Me,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 11. ↵

- Paul Haviland, “What 291 Means to Me,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 32. ↵

- Brinton, “Multum in Parvo,” 45; Arthur B. Carles, “291,” Camera Work 47 (January 1915): 40. ↵

- de Zayas, “291,” 73; de Zayas, “The Evolution of Form—Introduction,” Camera Work 41 (January 1913): 48. ↵

- de Zayas, “The Evolution of Form—Introduction,” 48. ↵

- Marius de Zayas, African Negro Art: Its Influence on Modern Art (New York: Modern Gallery, 1916), 10. ↵

- de Zayas, “African Negro Art, 10; and de Zayas, “The Evolution of Form—Introduction,” 45. ↵

- Héctor Calderón, Narratives of Greater Mexico: Essays on Chicano Literary History, Genre, and Borders, CMAS History, Culture, and Society Series (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004), 13–14, 33, 60–61. Although Calderón focuses in his study specifically on Mexican immigrants in the southwestern region of the United States, I suggest that his analysis provides a useful framework for understanding the way that de Zayas shaped his career after he resettled in New York. ↵

- Hodge Kirnon, “The Growing Recognition of Negro Culture,” The Promoter 1, no. 5 (September 1920): 5. ↵

- Kirnon, 5. ↵

- Kirnon, 6. ↵

- Kirnon, 6–7. ↵

- Greenough, “Alfred Stieglitz, Rebellious Midwife to a Thousand Ideas,” 50. ↵

- In one letter to Stieglitz, Kirnon comments on a public debate between the photographer and the art critic Thomas Craven that appeared in The Nation and an article on Stieglitz and 291 by the writer Herbert J. Seligmann for American Mercury. He also notes, in the same letter, that he was beginning to read Rosenfeld’s then–recently published Port of New York. Letter from Kirnon to Stieglitz, May 9, 1924, YCAL MSS 85, Box 28, Stieglitz Papers. ↵

- Letter from Kirnon to Stieglitz, May 9, 1924. ↵

- Brigman, “What 291 Means to Me,” 17. ↵

- Alain Locke, “A Note on African Art,” Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life, 2 (May 1924): 135–36. ↵

- Locke, 138. ↵

- Locke, 138. ↵

About the Author(s): Tara Kohn is a Lecturer in the Department of Comparative Cultural Studies at Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff