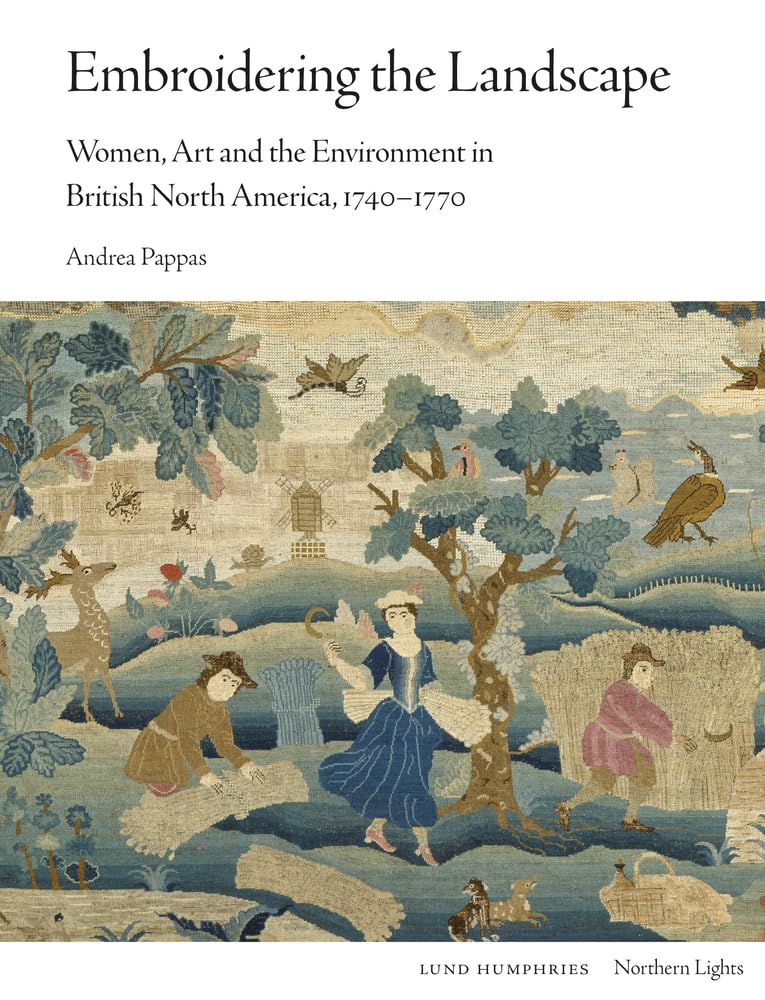

Embroidering the Landscape: Women, Art and the Environment in British North America, 1740–1770

PDF: Eager, review of Embroidering the Landscape

Embroidering the Landscape: Women, Art and the Environment in British North America, 1740–1770

By Andrea Pappas

London: Lund Humphries, 2023. 192 pp.; 40 color ills.; 30 b/w ills. Cloth: £50.00 (ISBN: 9781848226241)

In Hannah Otis’s embroidered textile View of Boston Common (ca. 1750), scarlet berries the size of human heads sprout jubilantly from the foreground, while a mix of animals, wild and domestic, frolic in the indeterminate space beyond (fig. 1). On either side of the composition, the carefully shaded bark of gnarled tree trunks contrasts with the pixelated sprays of leaves that decorate their upper reaches. Landmarks of eighteenth-century Boston, like Thomas Hancock’s house and the signal tower atop Beacon Hill, stand in recognizable relationship to their positions on period maps, even as the mill pond that occupied the city’s northern reaches has been relocated to the center of the Common. The scene presented is both enticing and bewildering, lush in its verdure but structured in ways that make unusual demands on the viewer.

The disorienting composition and disjunctive scalar shifts that characterize Otis’s landscape are commonly treated as signs of the embroiderer’s naiveté, evidence of the untrained eye and amateur hand wielded by young women in the production of domestic craft. However, as Andrea Pappas argues in Embroidering the Landscape: Women, Art, and the Environment, 1740–1770, to characterize such pictures as naive is to miss their “conceptual and perceptual complexity” (41). Over the course of nearly two hundred beautifully illustrated pages, Pappas unpacks the compositional conventions that make such landscapes intelligible alongside the broader landscapes of trade, agriculture, and husbandry from which these embroidered scenes originally emerged. The book is a welcome addition to a growing body of scholarship on women’s needlework and domestic craft in the eighteenth century. Like recent publications from Heidi Strobel, Serena Dyer, and Chloe Wigston-Smith (among others), this book moves beyond conventional questions of family history and women’s education to situate the production of needlework in histories of labor and trade, power and politics, empire and environment.1 Pappas, in particular, is concerned with environmental history and the way in which embroidered pictures produced in mid-eighteenth-century Massachusetts and Connecticut record women’s understanding of and engagement with the anthropogenic transformation of the region in the context of British colonialism.

Pappas has deftly structured the book like the landscape pictures in question. In line with her observation that the confounding “mix of near and far” that structures these embroideries also structured women’s relationship to nature in the eighteenth century, Pappas uses her chapters to move the reader from the most distant horizon—that of global trade—through the middle distance of fields and farms to the more intimate spaces of the kitchen garden (150). The first two chapters are global in scope, tracing a transoceanic flow of images and objects from which needleworkers drew inspiration while also documenting the ships, structures, and seascapes through which these items flowed. While acknowledging that the world both inside and outside the picture was the product of settler colonialism’s exploitative systems of territorial dispossession and enslavement, Pappas’s primary focus here is on the compositional conventions and visual technologies that gave this class of pictures their unique appearance, explained and interwoven as part of a globalized system of economic and intellectual exchange. Offering instructions on “How to Look at Colonial Embroidery,” Pappas reminds the reader that the elite young women who produced these pictures occupied a particularly rich visual environment, populated by Chinese export porcelain, palampore textiles from the Coromandel Coast, British printed chintz, and a wide range of printed material both European and domestic. This array of source material was also augmented by new forms of visual experience, made possible by mechanical aids to vision, like the spyglass. Pappas has thus coined the term “telescopic perspective” to formalize the sense of push and pull that these pictures exert on the viewer, connecting this unusual perspective to a temporal as well as spatial construction of the landscape and emphasizing the role of both movement and memory in the composition of the pictures’ spatial logic (37).

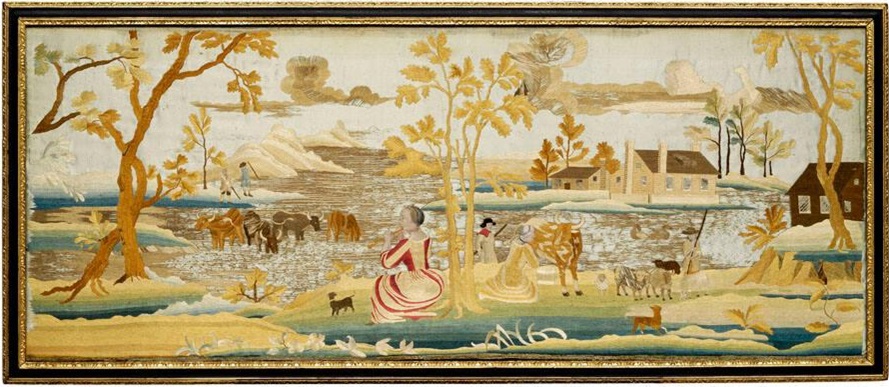

The middle two chapters address women’s experience of the landscape as a distant prospect in the fields, pasturage, and ponds that constituted the space of colonial agriculture and husbandry. Again, the framing of these chapters addresses the dispossession of Native communities and the legal structures enacted by colonial governments to undermine their property claims, but the primary focus is on the settler experience. As others have done, Pappas connects embroidered depictions of the agricultural landscape to the impact of Virgil’s Georgics on eighteenth-century Anglophone society. Offering an idealized vision of rural labor as well as practical advice on the cultivation of crops and the care of animals, the Georgics provided both aesthetic criteria and didactic instruction to a society that explicitly connected the concept of property ownership to the project of land “improvement.” Although previous discussions of this period’s embroidered pictures have focused on the aesthetic dimension of the georgic, Pappas takes a different approach, revealing the ways in which these pictures record an active awareness of contemporary farming techniques and the profound changes these techniques wrought on the American landscape. In her analysis of Faith Trumbull’s Seated Lady (1754), for example, Pappas draws our attention not to the elegantly attired figures in the foreground but to the muddy middle distance, where a herd of cattle are employed in “grazing down” an expanse of wetland—a practice that encouraged evaporation, the growth of new grass species, and thus the eventual repurposing of this area as fertile farmland (fig. 2). Further demonstrating her needleworkers’ attention to local specificity, Pappas also offers a deep dive into animal husbandry, the availability of certain breeds in the colonies, and the symbolic significance of fat, fluffy tails in embroidered representations of sheep. Countering the assumption that women’s lack of property rights also meant their lack of attention to or interest in its management, Pappas demonstrates her needleworkers’ continual engagement with both the practical and aesthetic dimensions of the local landscape’s physical transformation.

Turning in the final two chapters to a landscape closer at hand, Pappas takes her reader to the kitchen gardens overseen (if not always actively cultivated) by elite women as part of their broader household management. Where Virgil’s Georgics provided the literary counterpoint to the material knowledge displayed in the previous chapters, here Pappas offers a comparison with scientific texts on botany and zoology, such as Batty Langley’s Pomona, or The Fruit Garden Illustrated (1725) and Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands (1743). Paying careful attention to the dichromatic blush of apples on embroidered trees and the rendering of those supersized strawberries already mentioned (are their leaves trefoil or no? skins dimpled with seeds or with seeds protruding?), Pappas makes a convincing case for the botanical specificity of the needleworkers’ verdant landscapes. Likewise, her careful study of the coloring and form of one needleworker’s many stitched butterflies draws out the young woman’s own close observation of local wildlife. Far from slavish copies of the printed sources to which they are compared, these stitched descriptions of botanical and zoological specimens offer a more-than-textual record of women’s investment in both the practical and scientific knowledge of nature.

Across six compelling chapters, Embroidering the Landscape eloquently argues for a more vigorous engagement with both the specificities of individual embroideries and the broader social context in which they were created. I was particularly taken with Pappas’s insistence on the compositional complexity of these images and her resistance to accounts that treat their makers as mere copyists. Noting the way in which imitation and repetition were employed in other media (especially colonial portraiture) as tools to cement collective identity, Pappas positions the commonalities among this period’s embroidered landscapes as part of a broader project to forge familial and community bonds while also highlighting the specific differences that demonstrate each maker’s responsiveness to her own local environment. This effort to link embroidery and environment was only possible due to Pappas’s intensive research into the regional specificities of eighteenth-century agricultural practices and the unique genealogical histories of both historic and contemporary cultivars. It is an effort that has certainly borne fruit (so to speak). Reading her descriptions of New England’s newly drained wetlands and dammed waterways, it becomes impossible to imagine the embroidered pictures produced by the region’s young women to be anything but a response to the local environment. Pappas makes clear that the scale of the transformation taking place around them was simply too significant to be ignored. One comes away from the book with a clear sense of the changing environment as a site of active intellectual and physical engagement.

At the same time, the specificity with which Pappas can speak to these changes in the environment contrasts sharply with how little we know about the embroideries’ makers and the conditions of their manufacture. The unevenness of the historical record is precisely what Pappas seeks to redress, but it can feel at points throughout the text that the actual work of these young women has gotten lost amid the robust coverage of their fascinating context. There are, of course, exciting moments of crossover, such as a passage in the final chapter where Pappas notes that the tools and techniques of horticultural grafting are remarkably similar to those employed in embroidery. In the same vein, her careful attention to questions of color and fading in the embroidered pictures combined with her discussion of the kitchen garden’s varied contents bring to mind the botanical knowledge necessary in textile dyeing and thus the very tangible connections between gardens real and represented. It would have been fascinating to see Pappas probe further into such points of connection, fleshing out the pathways along which such material and technical knowledge might have flowed both to and from the needleworker, even if such inquiry required a certain degree of speculation. While deepening the reader’s appreciation of the embroiderer’s more-than-textual contribution to botanical and zoological knowledge, such an approach might also more explicitly situate the elite young women associated with these pictures among a broader network of innumerable unnamed figures—gardeners, field hands, housekeepers, maids, cooks, and other laborers—from whom such knowledge might have been gleaned or with whom it might have been shared.

As Pappas herself remarks in the final lines of Embroidering the Landscape, much more remains to be done to fully understand the complexity of these remarkable pictures. It is my hope that other scholars will soon follow suit and expand upon this already substantial body of research. Recognizing the intellectual inquiry and descriptive specificity of these embroidered pictures, Pappas has established a strong foundation on which to build a more diverse and ultimately more robust understanding of the ways in which the settler landscape was both physically and figuratively constructed in the eighteenth century.

Cite this article: Elizabeth Bacon Eager, review of Embroidering the Landscape: Women, Art and the Environment in British North America, 1740–1770, by Andrea Pappas, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 2 (Fall 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19272.

Notes

- See, for example, Heidi A. Strobel, The Art of Mary Linwood: Embroidery, Installation, and Entrepreneurship in Britain, 1787–1845 (London: Bloomsburgy, 2024); Serena Dyer, Labour of the Stich: The Making and Remaking of Georgian Fashionable Dress, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024); Chloe Wigston-Smith, Novels, Needlework, and Empire: Material Entanglements in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024). ↵

About the Author(s): Elizabeth Bacon Eager is assistant professor of art history at Southern Methodist University, Dallas.