Exanimate Subjects: Taxidermy in the Artist’s Studio

In the course of researching my dissertation “Animal Pursuits: Hunting and the Visual Arts in Nineteenth-Century America,” I have often had occasion to consider (and sometimes lament) the unequal relationships between humans and animals that are frequently pictured in art. I have found taxidermy to be a potent material embodiment of this power dynamic that somewhat surprisingly connects a wide variety of nineteenth-century visual history, encompassing the work of Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), Victorian home furnishings, academic painting, and other visual realms. While the presence of taxidermy in nineteenth-century life is well documented, it has been more challenging to trace its intersection with the fine arts. References to artists such as Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) who employed taxidermy in the studio are scattered throughout the literature on nineteenth-century art, but relatively little material or documentary record of the practice remains.1 I was thrilled, however, to find a piece of visual evidence hiding in plain sight within a photograph of the studio of William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) at the Archives of American Art that allowed for the concrete determination of an artist’s use of a taxidermy model in the construction of a painting. While this might at first seem a minor discovery regarding the history of a single painting, it opens up intriguing avenues of inquiry into issues of nineteenth-century studio practice, animal representation, and the ways in which art served to negotiate the relationship between humans and other species, which constitute the essay that follows.

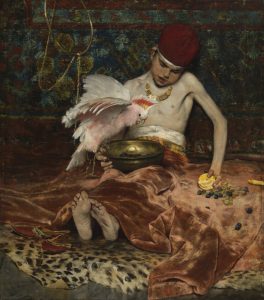

When Chase and Frank Duveneck (1848–1919) exhibited their closely related canvases The Unexpected Intrusion (The Turkish Page) and Turkish Page at the 1877 annual exhibition at the New York National Academy of Design, they attracted a great deal of attention as preeminent examples of the new direction in American art being pursued by young artists under the influence of the Munich Academy of Fine Arts (figs. 1, 2).2 The two works, painted together in Chase’s Munich studio the previous year, depict a young German boy dressed in Orientalist costume, seated in a sumptuously furnished interior, with a resplendent white and pink cockatoo perched upon his lap. Several critics singled out the technical bravado and skill of the painters at naturally representing the many varied surfaces within the scene, but also found fault in the staginess of the compositions and the artificiality of the overall subject. For example, after first praising Duveneck’s brushwork and use of color, a writer for the Atlantic Monthly, tempered this enthusiasm by adding, “The boy is plainly a model costumed for the occasion and surrounded by such easily arranged accessories as serve to give a hint of local color.”3 Although most critics acknowledged that the two works bore ample evidence of their status as studio concoctions, none recognized what was perhaps the paintings’ greatest conceit: the dazzling bird at the center of the two canvases was in fact not living but a taxidermy model, one of the many exotic objects that populated Chase’s studio.4

Despite Chase and Duveneck’s seeming disregard of the cockatoo’s sentience, the taxidermied animals that often appear in nineteenth-century paintings were never simply artists’ props or studio paraphernalia—mere inanimate objects—but were instead exanimate subjects, which when closely examined extend the discourse of nineteenth-century subjectivity in two of the key mediums of the period: animal and artist. Stripped of their agency prior to entering the studio, these animals were reanimated by the hand of the artist into fully formed subjects upon the canvas. On the one hand, taxidermy presented a technological solution to the problem of working with unpredictable creatures as models. However, the complete removal of animals from the act of their own representation through the killing, stuffing, and mounting of formerly living beings as taxidermy models, must also be considered as part of the larger process by which industrialization and urbanization divorced humans both physically and culturally from other animals. While animal subjects were traditionally held in low esteem within academic hierarchies (as well as art historical scholarship), a more thorough interrogation of the material processes of animal representation yields new insights into the ways in which images worked more broadly to structure the imperious relationship humans have to the natural world.

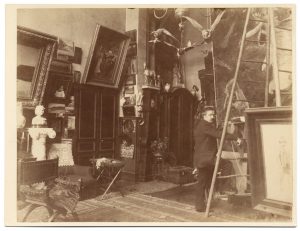

During his stay in Munich, Chase produced at least two other paintings that incorporated the taxidermy cockatoo: The King’s Jester (1875; private collection) and Serenade to a Cockatoo (1875; location unknown), as well as a canvas depicting Duveneck at work on his version of the Turkish Page (Cincinnati Art Museum).5 The avian model for the Chase and Duveneck paintings appears again, frozen in the same pose, in the upper right corner of a photograph taken in Chase’s New York studio around seven years after the paintings were produced (fig. 3). An 1879 article published only a year after Chase opened his Tenth Street studio, also described an encounter with the stuffed bird: “Over the door by which we enter, and which fronts the end of the studio just described, is the head of a polar bear, grinning down on three white-and-pink stuffed cockatoos perched on a screen—the frigid zone and the torrid in juxtaposition.”6 Clearly Chase possessed a strong affinity for the winged model, carrying it to New York and holding onto it for many years even after he had seemingly exhausted its painterly potential.

The use of mannequins, lay figures, and other studio props as stand-ins for human models was a common practice among artists since the Renaissance.7 Although strict academic principles privileged the study of the living model, the practicalities of life in the studio—in which the model’s time and artist’s money were often in short supply—spurred many artists to seek inanimate substitutes. During the late nineteenth century, the disjunction between the living figure and the lifeless model became a recurrent theme in the work of numerous forward-thinking artists who showed little adherence to academic standards which sought to downplay or disguise practical aspects of the artist’s craft. Shown in the fourth Impressionist exhibition, Edgar Degas’s (1834—1917) Portrait of Henri Michel-Lévi (c. 1878; Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon) depicts Degas’s friend, a lesser known artist associated with the Impressionist circle, surrounded by his paintings of boisterous scenes of bourgeois people engaged in outdoor leisure. Michel-Lévi stares forward sullenly while a life-sized mannequin clad in a stylish pink dress and bonnet sits crumpled at his feet.8 While Degas’s work presents a sardonic view of the discord between studio artifice and outdoor reality, John Ferguson Weir’s (1841—1926) His Favorite Model seems to revel in the uncanny relationship between the lifeless model and the dynamic painter (fig. 4). Such paintings have deep roots in Western artistic traditions, calling to mind the myth of Pygmalion, the sculptor whose intense love for his ivory statue moved Aphrodite to bring the sculpture to life. By the late nineteenth century, images that emphasized the inner workings of the studio and the special role of the artist in transforming the artificial into the natural gained particular resonance in an era of rampant industrialization and mechanization.

During the eighteenth century, the scientific impulse of the Enlightenment led many artists to seek a more direct understanding of animal subjects, based on close, firsthand observation of their bodies. In England, George Stubbs (1724—1806), then a young portraitist, spent several years from 1756 to 1759 on a farm in Lincolnshire dissecting horses in order to make drawings from every aspect of their interior and exterior anatomy. These intricately detailed studies became the basis for his engraved 1766 volume Anatomy of the Horse. Though working from dissected bodies, Stubbs endeavored in the plates to depict the animal as if in motion, through multiple perspectives of its anatomical structure, thereby reanimating the deceased specimens upon the page. He presented the volume as a resource for veterinarians and horse breeders, but also promoted its utility for painters and sculptors whose work might benefit from a more thorough description of the animal’s underlying structures. 9

Several decades later in the United States, Charles Willson Peale (who also began his career painting portraits) pursued a different method of more precisely representing animal bodies, which he displayed in his Philadelphia museum. Peale revolutionized the fledgling practice of taxidermy by inventing a method of preserving animal skins against the ravages of time, mold, and insects by immersing them in an arsenic solution.10 This process allowed the skins to retain the natural brilliance of their fur or feathers, while still leaving them pliable enough to be shaped over lifelike mannequins, which Peale often posed in a dramatic fashion. Peale’s taxidermy exhibits served primarily as didactic tools for teaching natural history but he also recognized their potential value for artists proclaiming, “The mussils [sic] of … many of these quadrupeds are so well [presented] that Painters might take them for models.”11 Throughout the nineteenth century, an array of artists who depicted animal subjects from John James Audubon (1785—1851) to Martin Johnson Heade (1819—1904) followed Stubbs’s example and Peale’s advice, modeling their works largely on the bodies and skins of dead animals.

By the second half of the nineteenth century, taxidermy had expanded well beyond the specialized realm of natural history to become a widespread cultural phenomenon. Stuffed animal specimens could be found decorating fashionable homes as well as taverns. Taxidermy shops flourished in many American cities, which churned out hundreds of specimens for both burgeoning natural history institutions like the American Museum of Natural History as well as private customers.12 The enthusiasm for mounted animals was echoed in Europe where firms like Deyrolle, founded in Paris in 1831, grew into large-scale taxidermy factories supplying specimens throughout the Continent. In England, designers constructed extravagant chairs, lamps, and fire screens out of animals’ bodies and skins that combined the fantastical with a hint of the grotesque.13 While in the United States, art periodicals such as The Art Amateur published guides for those amateur taxidermists and artists who wished to learn the craft for themselves.14

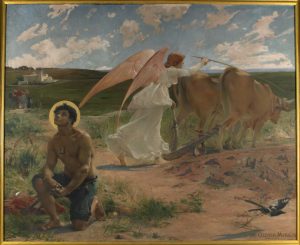

Considering the ubiquity of taxidermy in nineteenth-century life, it is unsurprising that artists would exploit such objects as stand-in models when depicting animals. Contemporary studio photographs and written accounts document the presence of taxidermy in the studios of a range of academically trained artists in addition to Chase, such as Jean Léon Gerôme (1824—1904), Hans Makart (1840—1884), and Luc Olivier Merson (1846—1920) (fig. 5).15 In many cases these objects functioned primarily as part of the overall eclectic decorative scheme of the studio, signifiers of the artist’s wide-ranging and refined aesthetic interests. However, in some instances specific references to the animals mounted in the studio can be found in an artist’s work, such as the magpie that appears in the lower right of Merson’s St. Isidore the Plowman flying rightward out of the composition (fig. 6). The bird appears practically identical in pose and coloring to the stuffed magpie seen hanging in his studio in the later photograph. Although taxidermy specimens commonly inhabited the studio space, their status as aids in the production of art was rarely acknowledged or discussed. At a moment when artists were engaged in examining the interplay between the real and the imagined by calling attention to the use of mannequins and lay-figures, animals were almost always presented as straightforward depictions of living creatures. For many painters, it would seem the stark existential differences between a taxidermied animal, frozen forever in a single pose, and a living, sentient creature was of little consequence.

Indeed most of the viewers who encountered works such as Chase and Duveneck’s portrayals of the Turkish page, which depended upon taxidermy, simply took for granted that they were observing a true likeness of a living creature. Despite the utter lifelessness of the stuffed cockatoo, the lively manner in which the two painters portrayed the animal led contemporary observers to describe the bird in highly active terms. One critic described the boy’s eyes as “listlessly following the movement of the bird,” while another surmised that the cockatoo must be in the act of feeding.16 That the particular species of cockatoo depicted was not native to Turkey where the scene was purported to take place, or Europe where it was created, did not seem to elicit any attention. An assurance of the animate nature of the cockatoo persisted in the literature on the paintings well into the twentieth century. Several years after the debut of the work, William C. Brownell proclaimed that Duveneck had rendered “the bird’s plumage as feathery as one might see in nature,” while a later biographer declared the bird “a vivacious and sturdy member of the parrot family.”17

Critics who encountered the paintings paid particular attention to the young boy, remarking upon the form of his body, but also carefully considering his inner character, commenting upon his pitiable condition, and debating whether he adequately embodied a Turkish youth or remained too much the German model.18 When discussion turned to the cockatoo, some writers pondered the narrative role of the bird, but most frequently their observations about the animal focused on the naturalistic way in which each painter rendered the feathers and other surface effects, comparing these to the other luxurious objects on display in the studio.19 Contemporary viewers were well trained to consider the interior complexity of human figures in art, but when it came to animals, there was little concept of inner life beyond a creature’s external appearance.20

This near total erasure of the subjectivity of the animal throughout the process of the production and reception of the artwork exemplifies John Berger’s concept of the “cultural marginalization” of animals. By the late nineteenth century, the processes of industrialization and urbanization had already significantly reduced the physical presence of animals in modern life. The physical displacement of animals from the human sphere in capitalist society precipitated a conceptual transformation that fostered a diminished cultural view of animals. As Berger writes, “The animals of the mind, instead of being dispersed, have been co-opted into other categories so that the category of animal has lost its central importance.”21 The animals that inhabited artists’ studios were plucked by the taxidermist from the normal biological cycle of life, death, and decay in order to service human needs. In the case of Chase and Duveneck’s cockatoo, despite its dramatic pose, the bird functions mainly as a lavish decorative object, contributing to the fiction of the far-flung locale of the scene and appealing to contemporary fascination with the exotic.

Taxidermied animals have never rested as comfortably in the object category that many nineteenth-century artists seemed content to consign them. As Rachel Poliquin has argued, “An animal—even if taxidermied—is not an arbitrary object, materiality indistinguishable from a bowl or a painting . . . This uncanny animal-thingness of taxidermy has the power to provoke to edify, and even undermine the validity of its own existence.”22 That most contemporary observers chose to interpret Chase and Duveneck’s cockatoo as a subjective, living being speaks to the power of taxidermy to transcend its object status, but also to the capacity of painting to creatively reanimate static specimens. Despite the indeterminate position of taxidermy between object and subject, Chase, Duveneck, and many other painters seemed wholly uninterested in deeply exploring its peculiarities to the same degree as those artists who readily depicted human mannequins and lay figures among living figures. Instead the larger compositional and thematic goals of the work (in this case, the attempt to create an Orientalist tableau) ultimately overwhelmed attempts at renewing the subjectivity of the animal.

As Chase matured as an artist, he moved beyond his academic training and developed a more overtly naturalistic manner. Chase did continue to depict animal subjects, but these were still lifes of dead fish, rather than the lively posed cockatoo or similar creatures. When he closed his Tenth Street studio and auctioned its contents in 1896, several stuffed birds were listed in the sale catalogue, but the pink and white cockatoo was not included among them.23 Late in his life Chase wrote on the subject of painting, “Truth is the practical ideal that the art of painting insists upon . . . . To me, the essential value of a picture is whether it has been well seen by the artist, whether he has been faithful in his translation, or whether he has imposed upon the truth to impress upon us an elaboration of his own.”24 Chase’s treatment of the stuffed cockatoo might at first seem to qualify for the final category mentioned, as his own elaboration of natural truth. However, such a reading fails to take into account the decidedly unnatural state of taxidermy that was composed of real animal tissue, but posed and articulated by a human taxidermist well before the creation of the painting.

Edward H. Coates Memorial Collection).

That Chase quickly moved away from the practice of using taxidermy as studio props would seem to indicate an awareness of the futility of trying to synthesize nature by modeling his work after a convincing forgery.25 However, other artists were not so easily deterred. While in Paris studying under the French academic painter, Alexandre Cabanel (1823–1889), Thomas Hovenden (1840–1895), created the elaborate costume piece, The Favorite Falcon in 1879 (fig. 7).26 Perhaps surpassing Chase and Duveneck in terms of sheer contrivance, Hovenden concocts an elaborate fiction of courtship in the painting by means of the lush setting and the costumes and poses of the human models. While no tangible evidence yet exists to prove that Hovenden’s bird was modeled from taxidermy, the practicalities of academic studio practice at the time make this possibility quite likely. More importantly, the utilization of the falcon within the painting conforms perfectly to the paradigm in both painting and other cultural forms of modern society in which nonhuman animals functioned only as contributors to human meaning, rather than fully developed subjects of their own.

The disregard with which the subjectivity of animals is treated within such images resulted from the interpretation and reception of paintings among a public increasingly unaccustomed to contact with other species, but was also deeply rooted in the material processes by which art was created in artists’ studios throughout the late nineteenth century. The discovery of Chase’s stuffed cockatoo has clarified my understanding of the fraught encounter between artist and animal, and continues to inform my research into the representation of hunting in American art. Such encounters never occur on neutral ground (particularly in images that depict animal death), but always exemplify the unequal relationship between human and animal, subject and object.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1549

PDF: Piper – Exanimate Subjects

Notes

- Shao-Chien Tseng, “Contested Terrain: Gustave Courbet’s Hunting Scenes,” The Art Bulletin 90 (June 2008): 220. ↵

- “The Contributor’s Club,” The Atlantic Monthly 40 (July 1877): 105. ↵

- “Recent Literature: Art,” The Atlantic Monthly 39 (May 1877): 641–42. For other critical appraisals see “The Academy Exhibition,” The Art Journal 3 (1877): 157; “The National Academy Exhibition, 1877,” Scribner’s Monthly 14 (June 1877): 263; “Paintings: The Exhibition of the National Academy of Design,” New York Commercial Advertiser (April 2, 1877), 3; “Pictures in the Spring Exhibition,” New York Daily Graphic (April 6, 1877), 3; “Fine Arts” New York Evening Mail (April 16, 1877), 1; “At the Academy,” New York Daily Tribune (April 7, 1877), 5. ↵

- For more on Chase’s studio environment see Nicolai Cikovsky, Jr., “William Merritt Chase’s Tenth Street Studio,” Archives of American Art Journal 16 (1976): 2–14; and Bruce Weber and Sarah Kate Gillespie, Chase Inside and Out: The Aesthetic Interiors of William Merritt Chase (New York: Berry-Hill Galleries, 2004). ↵

- Ronald G. Pisano with D. Frederick Baker and Carolyn K. Lane, William Merritt Chase: The Complete Catalogue of Known and Document Work, vol. 4 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), catalogue number F. 4, F. 5, and I.5. ↵

- John Moran, “Studio Life in New York,” The Art Journal 5 (1879): 345. While Chase did own living exotic birds that he kept as pets, the identical pose of the cockatoo across several paintings as well as the studio photograph make it practically certain that he used the same taxidermy model. ↵

- For a thorough history of the mannequin in art, see Jane Munro, Silent Partners: Artist and Mannequin from Function to Fetish (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014). ↵

- Theodore Reff, “The Pictures within Degas’s Pictures,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 1 (1968): 150–54. ↵

- Christopher Lennox-Boyd, Rob Dixon and Tim Clayton, George Stubbs: The Complete Engraved Works (London: Stipple Publishing Limited, 1989), 295–312. ↵

- On Peale and taxidermy, see David R. Brigham, “Ask the Beasts and They Shall Teach Thee: The Human Lessons of Charles Willson Peale’s Natural History Displays,” Huntington Library Quarterly 59, nos. 2/3 (1996): 182–206. ↵

- Charles Willson Peale, “A Walk through the Philadelphia Museum,” unpublished manuscript, 1805. Collected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and Family, vol. 2, Series II-D. (Millwood NJ: Kraus Microform, 1980). ↵

- See Mark V. Barrow Jr., “The Specimen Dealer: Entrepreneurial Natural History in America’s Gilded Age,” Journal of the History of Biology 33 (Winter 2000): 493–534. ↵

- William G. Fitzgerald, “A Curious and Interesting ‘Fad’ in Furniture,” The Decorator and Furnisher 29 (November 1896): 42–3. ↵

- J.B. Holder, “Amateur Taxidermy,” The Art Amateur 1 (July 1879): 40–41. ↵

- Photographs of Gerôme and Merson’s studios can be found in the collection, Photographs of artists in their Paris studios, 1880–1890. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution and Makart’s studio is illustrated in F.G. Dumas, Illustrated Biographies of Modern Artists, vol. 3 (Paris: L. Baschet, 1882), 213–14. ↵

- “Recent Literature: Art,” The Atlantic Monthly 39 (May, 1877): 641; “The Academy Exhibition,” The Art Journal 3 (1877): 157. ↵

- William C. Brownell, “The Younger Painters of America,” Scribner’s Monthly 20 (May 1880): 4; Walter Montgomery, ed., “Frank Duveneck,” American Art and American Art Collections: Essays on Artistic Subjects (Boston: E. W. Walker and Co., 1889), 985. Similar descriptions persist through the present literature. For example the entry in the Chase catalogue raisonné for The King’s Jester (F. 4) reports: “In the background of the work under consideration a cockatoo flies about freely, not distracting the jester at all from his task at hand.” Ronald G. Pisano with D. Frederick Baker and Carolyn K. Lane, William Merritt Chase: The Complete Catalogue of Known and Document Work, vol. 4, 131. ↵

- For considerations of the model’s nationality see, “Recent Literature: Art,” The Atlantic Monthly 39 (May 1877): 641. ↵

- For discussion of the surface effects see, “The Contributor’s Club,” The Atlantic Monthly 40 (July 1877): 105 and “At the Academy,” New York Daily Tribune (April 7, 1877), 5. ↵

- There were a few exceptions of artist’s who explored the interior nature of animals such as Edwin Landseer, but these were largely considered animal specialists. ↵

- John Berger, “Why Look at Animals?,” in About Looking (New York: Vintage Books, 1992), 15. ↵

- Rachel Poliquin, “The Matter and Meaning of Museum Taxidermy,” Museum and Society 6 (July 2008): 127. See also Rachel Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012). ↵

- Catalogue of Paintings, Studio Appointments, Curios, Bric-a-Brac, A Unique Collection of Finger Rings, Etc. Etc., Belonging to William Merritt Chase, N.A. (New York: The American Art Association, 1896), 36. ↵

- William Merritt Chase, “Artists’ Ideals, The Aims of Painters and Actors,” The House Beautiful 23 (February 1908): 11. ↵

- Chase was certainly not alone in his inability to resolve the complex interplay between living and deceased animal matter. Such questions have continued to intrigue artists such as Damien Hirst and Hiroshi Sugimoto to the present day. ↵

- Susan Danly, Telling Tales: Nineteenth-Century Narrative Painting from the Collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (New York: American Federation of Arts, 1991), 75. ↵

About the Author(s): Corey Piper is a doctoral candidate at the University of Virginia.