Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina

PDF: Rothschild, review of Hear Me Now

Curated by: Adrienne Spinozzi, Associate Curator, American Wing, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Ethan W. Lasser, John Moors Cabot Chair of the Art of the Americas Department, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and Jason R. Young, Associate Professor of History, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Exhibition schedule: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (September 9, 2022–February 5, 2023); Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (March 4–July 9, 2023); University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, MI (August 26, 2023–January 7, 2024); High Museum of Art, Atlanta (February 16–May 12, 2024)1

Exhibition catalogue: Adrienne Spinozzi, ed., Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina, exh. cat. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Yale University Press, 2022. 200 pp.; 154 color illus. Hardcover: $45.00 (ISBN: 9781588397263)

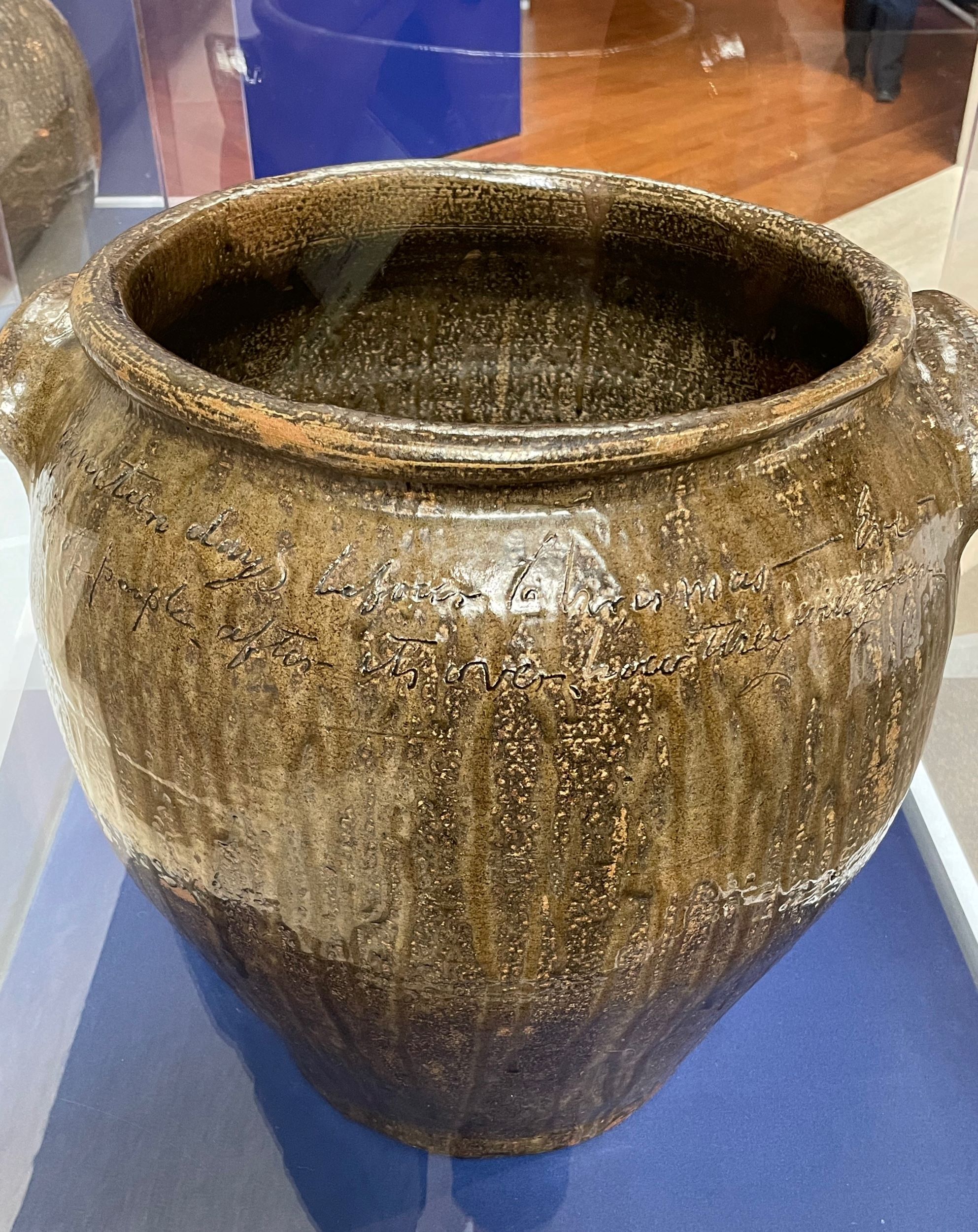

An enormous brown ceramic vessel beckoned visitors toward the entrance of Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina at the show’s first venue, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 1). An earthy-green glaze drips down the stately jar—a term that seems far too humble to describe the massive two-foot-tall container. An incised inscription on one side reads: “A very Large Jar which has 4 handles = / pack it full of fresh meats—then light candles,” denoting its intended use as a preservation container for meat, likely on a nearby plantation.

Its creator—Dave, later documented as David Drake (about 1801–1870s)—signed his name in a large script across the jar’s shoulders. (I will continue to refer to the artist as Dave, following the decision to do so within the exhibition.)2 Dave also inscribed the initials of Lewis Miles (1808–1868), his enslaver and the owner of the Stoney Bluff Manufactory where this jar was made, as well as the date of its production.

This stunning example of pottery announces the goal of Hear Me Now from the start: to celebrate the enslaved Black potters, known and unknown, of a distinctive, nineteenth-century ceramic tradition in the Old Edgefield District of South Carolina. Dave’s skilled facture of uncommonly large storage jars featuring evocative poetic verses has become widely known and celebrated within American art collections in recent years. Less frequently highlighted in this context are the products of other enslaved potters and laborers of African descent who worked in one of twelve pottery manufacturing sites in antebellum Edgefield.

Hear Me Now intentionally centers the Black individuals whose labor has long been present in such objects but whose authorship and creativity has not always been acknowledged. The show asks us to hear the stories these objects can tell about creative expression and craft under the conditions of industrial chattel slavery, about the resilience to make and mark one’s work when that claim to self-possession faced great challenges, and about the continued narrative and aesthetic force of Edgefield ceramics today.

The curatorial team—Adrienne Spinozzi, Ethan W. Lasser, and Jason R. Young—model a collaborative approach that increasingly defines curatorial praxis and that, as they assert, is both logical and imperative for a show like Hear Me Now. The exhibition emphasizes multivocal interpretation, nuanced historical context, attentive visual analysis, and tangible connections to the present moment and artistic production today in order to celebrate, analyze, and interpret the labors of enslaved creators within the fine art museum. It comes at a time in which many museums with historic American art collections are ardently striving to incorporate a greater diversity of makers, subjects, and interpretative perspectives into the narratives that they present.

So many questions surrounding the pottery from nineteenth-century Edgefield remain unanswerable. Informed speculation is, as a result, a necessary methodology for the ceramics’ analysis, and some of the most exciting moments in the exhibition came from the speculation or opinions provided by a wide range of contributors in labels and in the audio guide.3

The first of the exhibition’s five sections (in the Met’s installation) features a display of ceramics by Dave—the only enslaved artisan in Edgefield to have signed his own work—that includes an impressive gathering of twelve jars by the potter. The remainder of the exhibition explores the themes “Clay Beginnings,” “A Community of African American Potters,” “Faces of the Diaspora,” and “Edgefield and Contemporary Art.” Within these sections, the range of ceramics produced at Edgefield was made evident, from utilitarian containers for butter or syrup, to elaborately painted jars with narrative, figural scenes dancing across their surfaces, to the enigmatic practice of face vessels.4

The exhibition section “Dave: A Potter and a Poet” showcases the creator’s varied technical approach to ceramics and his sophisticated lyrical practice, the latter explored further by Michael J. Bramwell and Lasser in their catalogue essay. The gallery interpretation uses close visual analysis of Dave’s words and pottery to introduce a deeper historical and social context for the objects he produced. Dave created modest jugs—more typical of Edgefield pottery manufactories’ output—as well as uncommonly large storage jars with a forty-gallon capacity. His pottery features the green-brown tones of the site’s distinctive alkaline glaze, made from area lime or wood ash. Some objects feature a nearly seamless application of glaze, while others show the irregular, rhythmic drips that Dave seems to have relished.

Dave offered windows into his beliefs and worldview through the words that he carved into his jars at a time when it was illegal for those enslaved in South Carolina to read or write. On multiple vessels, Dave appears to critique the inhuman practices of chattel slavery. An 1857 jar featuring what might be the artist/poet’s most repeated verse—“I wonder where is all my relation / Friendship to all—and every nation”—is joined by another that speaks to the trauma of forced familial separation within a slave system: “nineteen days before Christmas—Eve— / Lots of people after its over, how they will greave” (fig. 2).

Jars made by Dave touched the lives of those with whom they made contact, and his inscriptions acknowledge those interactions. One label describes “the weekly social ritual known as ‘allowance day,’ when enslaved families . . . gathered to receive their rations,” an event at which Dave’s jars would have been at the center. There, his words, or, at least, the highly visible presence of his writing, would have signaled a bold, dangerous resistance to the South Carolina policy of forced illiteracy. Describing the jars’ use for the preservation and storage of meat also invites viewers to think about the enslaved men and women who smoked, salted, and brined meats, sealed the jars with wax, lugged the heavy containers in and out of storage, and cooked the stored meat on area plantations, handling Drake’s jars and viewing their words in the process.

As his own inscriptions sometimes indicated, Dave worked collaboratively, and through his literacy and practice of signing his work, he gave credit to potters who may have otherwise remained anonymous. An inscription from an 1859 storage jar reads: “• Mark and / • —Dave— / L • m • March 10 • 1859.” According to one account of Dave, he had lost a leg in a train accident.5 As a result, he would have needed help in aspects of his process, likely in pressing a foot-pedal mechanism that turned the wheel. We can envision other enslaved laborers working in the Edgefield manufactories bringing him materials and helping to carry his large creations in and out of the kiln.

The section “Clay Beginnings” provides an overview of the origins of the Edgefield stoneware tradition, which dates to the 1820s. This industry grew rapidly as a result of several factors: extant kaolin clay deposits that made ceramic production possible, a desire from buyers in the region to find an alternative to imported ceramics, and a local enslaved labor force to support large-scale pottery production. Gallery texts illuminate the complexity of labor at Edgefield pottery sites beyond the crafting of the objects on display: “African Americans . . . developed the specialized skills necessary for mining and processing clay, constructing sophisticated kilns, felling, hauling, and seasoning lumber for fuel, as well as managing multiday firings of kilns that spanned more than 100 feet in length.”

Reaching beyond a Black-white binary, this section also introduces a vital, underexamined area of inquiry within Edgefield studies—the relationship that this nineteenth-century stoneware practice had to Indigenous potters and pottery traditions of the region. The use of clay in the region to make ceramics by Catawba Indian Nation potters predates the industry’s establishment by thousands of years, and this section of the exhibition includes a bowl from about 1500 as well as a contemporary Cupid jug (2000) by Catawba Indian Nation artist Earl Robbins to illustrate this deep, continuous tradition. However, many questions remain about the potential exchange of ceramic knowledge that occurred in the nineteenth century between Indigenous potters and those working in the industry in Edgefield—an important avenue for future research.

The community of Black makers at the region’s many sites of pottery production and the presence of their now-anonymous craftsmanship are explored through the remaining examples of Edgefield pottery in Hear Me Now. By labeling the majority of ceramics as produced by an “Unrecorded Potter,” the curators prompt us to question the idea of authorship as it manifests in a signature or maker’s mark. This decision departs from the typical attribution of Edgefield ceramics only to the site or site owner, whose name appears on the objects. These unnamed potters come to the fore in an especially compelling vitrine that includes a jar, churn, pitcher, and fragment, all associated with the potteries of the white ceramicist Thomas M. Chandler Jr. (1810–1854), who enslaved four craftsmen (fig. 3). Slight differences of facture across these examples attest to multiple hands at work in their creation, but a recurrent decorative motif suggests their makers were directed to recreate the pattern as a hallmark of the site, one that subsumed their individual contributions.

Several unexpected, highly decorated objects, adorned with figures that appear to be of African descent, were on display nearby, visualizing the presence of Edgefield’s enslaved residents. On a watercooler made by an “Unrecorded Potter,” a Black male and female figure clink their glasses together in a celebratory scene that may represent a wedding. The gallery texts reveal that some of these examples could have been made by the white potters Chandler Jr. or Collin Rhodes (1811–1881), and thus this section also prompts viewers to negotiate how they, and how an institution or scholarship, should treat the art of the enslaver. The way in which this exhibition brings together their potential work, while highlighting the enslaved craftsmen who made and shaped many additional works on view, offers a compelling case study.

Several cases display the iconic face vessels of Edgefield (fig. 4), a practice dating from the 1850s. These ceramic jugs with carved faces and often unglazed white kaolin eyes and teeth were only produced by African-descended makers and reflect a tradition apart from the utilitarian stoneware that the same artisans were otherwise forced to manufacture. The exact function of face vessels is unclear, and they may have been varied. Yet the exhibition affirms a lineage of studies on these objects that ties them to African spiritual practices.6 Kaolin was seen as a substance that could summon the dead in African spiritual sculptures, as the gallery text explains, which leads to the understanding that face vessels may have been used to conjure spirits. Evidence of this is found in the face vessel on display once owned by African American ritual expert Mamie Deveaux (1906–1983)—her matchbook still stuck on the inside of the jar. Young explores the connections between Edgefield ceramics and funerial traditions of West-Central Africa and its diaspora in one of the catalogue’s most original contributions.

While the majority of the face vessels are not firmly dated and could have been made before or after the Civil War, Hear Me Now does not focus on postbellum nineteenth-century Black pottery and the lives of artisans after emancipation. This is, in part, a challenge emerging from an absent archive, but the question of what these potters made and how they lived in the last quarter of the nineteenth century deserves further scholarship. Additional research is also needed on the geographic dispersal of their knowledge beyond Edgefield, as well as the transition between the Black production of face vessels and the predominantly white practice that began at the turn of the twentieth century.

What the exhibition achieves through the visual evidence of Edgefield ceramics alone is impressive and thought-provoking, although at times I wished for a greater presence of additional materials to more fully bring the story of “an African American community of potters” to light. Some visitors to Hear Me Now may have been fortunate enough to see the exhibition Crafting Freedom: The Life and Legacy of Free Black Potter Thomas W. Commeraw at the New-York Historical Society (January 27–May 28, 2023), curated by Margaret K. Hofer, Allison Robinson, and Mark Shapiro. In addition to the display of dozens of the New York–based potter’s signed or attributed works, the exhibition richly contextualized his practice with primary source documents, other artworks of the time, and didactics about his process. While there is something to be gained by placing the objects of Edgefield into the art-museum vitrine, some archival material would have visibly illuminated the nature of artisanship under enslavement in Hear Me Now.

A final section draws together a selection of contemporary artists whose work builds on the legacy of Black potters at Edgefield. In many ways, Simone Leigh’s (b. 1967) colossal white-glazed Large Jug (fig. 5), covered in giant cowrie shell forms, demands the most attention. Leigh recently represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2022, and her visibility in the art world, as well as that of Theaster Gates (b. 1973), whose work Signature Study (2020) is also included, adds cachet to the premise of this section—that the work of enslaved potters in nineteenth-century Edgefield indelibly shaped the trajectory of American art and craft histories and continues to do so. Some of the artworks by these artists directly reference Edgefield traditions, while others draw connections to the past through shared materiality, like Adebunmi Gbadebo’s (b. 1992) K.S. (2021) and In Memory of Pirecie McCory, Born 1843, Died June 10 1933, In They Place to Stand, HFS (2022), which physically incorporate South Carolina clay from the plantation in Fort Motte, where the artist’s ancestors are buried.

Bringing together so many works from Edgefield, and by Dave in particular, within Hear Me Now should be lauded. Excepting the inscribed vessels by Dave, these ceramics were not singular works of art but made in multiples. They benefit from being seen with other kindred examples, since the collective evokes the many artisans who labored at Edgefield and the repetitive acts of their service. Groups of similar objects also keep these jars from the hurdle many encounter in the art museum context—being the only thing like them and often “other” to the traditional fine art that surrounds them.

Perhaps the greatest impact of the exhibition will be its presentation of Edgefield ceramics within several major fine art museums, implicitly arguing that these objects should be considered among the canonized art history those institutions represent. And yet this exhibition does not seek to situate the work of Dave or his contemporaries within a Euro-American art-historical context, allowing the chorus of Black potters to sing together and on their own terms. As a result, I was left wondering how the voices of Black Edgefield potters can continue to be heard when these objects return to their home institutions. How do we ethically place an unadorned jar by Dave or an unrecorded artist next to contemporaneous paintings, sculptures, or decorative art that otherwise populate the historic American art gallery? Should such objects anchor a discussion about art and enslavement, a topic that continues to be underprobed in many museums’ collections, or does that conversation delimit the possible narratives around such works? Could these ceramics not initiate a powerful interrogation of traditional art objects and the institutions that house them on the subject of value and authorship, finish, singularity, and media? Curators, scholars, and museum visitors must confront these challenging questions that will reverberate long after Hear Me Now concludes its tour.

Cite this article: Jill Vaum Rothschild, review of Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 2 (Fall 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18431.

Notes

- Katherine Jentleson, a Co-Executive Editor of Panorama, is one of the coordinating curators for the High’s presentation of Hear Me Now. ↵

- Authors in the exhibition catalogue argue for and against the use of “Dave,” the name used by the artist to sign his work, and “David Drake,” the name by which he was recorded in public records after emancipation. During the period from which most of his ceramics date, the artist was enslaved, and like the majority of bonded Africans and their descendants in the United States’ chattel slave system, he was only ever referred to by a given name. In records following his emancipation, the artist appears as David Drake. Some contributors, and many institutions, refer to the potter and poet as “David Drake” in the belief that the artist chose this name after emancipation when he was able to do so, considering this act an expression of his freedom and its use as “a posthumous act of repair,” in the words of historian Vincent Brown. Others elect to use “Dave” for the reason that he signed his name this way or because Drake was the surname of the artist’s former enslavers, meaning that it may not have been chosen but rather forced upon him amid bureaucratic needs of census taking and other recordkeeping of the state. However, Brown also offers a compelling reason to sit with the artist as “Dave”: “Perhaps we should be hesitant to overrule the humility of his signature. Indeed it might be key to understanding the relationship between the abuses Dave suffered, the injuries that burdened his life, and the work of his own hands.” Brown, “The Art of Enslaved Labor,” in Adrienne Spinozzi, ed., Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Yale University Press, 2022), 17–18. ↵

- The audio guide can still be accessed on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website: https://www.metmuseum.org/audio-guide/playlists/edgefield. ↵

- The literature review in Adrienne Spinozzi’s catalogue essay covers the field’s evolving understanding of the function of face vessels: “Confronting, Collecting, and Celebrating Edgefield Stoneware,” in Spinozzi, Hear Me Now, 26–49, and 183–85. ↵

- This biographical fact came from an oral history interview from the 1930s. In their catalogue essay, Michael J. Bramwell and Ethan W. Lasser speculate that Dave’s loss of a leg could have actually been a form of punishment stemming from his writing; “Incidents in the Life of an Enslaved Abolitionist Potter Written by Others,” in Spinozzi, Hear Me Now, 55–56, 186n15. ↵

- For key examples of this approach, see Robert Farris Thompson, “The Structure of Recollection: The Kongo New World Visual Tradition,” in Robert Farris Thompson and Joseph Corner, The Four Moments of the Sun: Kongo Art in Two Worlds (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1981),157–59; John Michael Vlach, “Pottery,” in The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1978), 81–94; and Claudia A. Mooney, April L. Hynes, and Mark M. Newell, “African-American Face Vessels: History and Ritual in 19th-Century Edgefield,” in Ceramics in America (Milwaukee: Chipstone Foundation, 2013), 3–37. ↵

About the Author(s): Jill Vaum Rothschild is a Luce Curatorial Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.