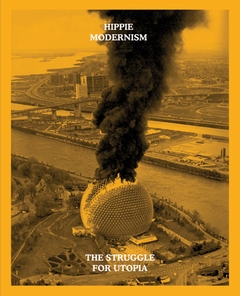

Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia

Edited by Andrew Blauvelt

Exh. cat. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 2015; 448 pp.; 200 color ills.; $55.00; ISBN: 9781935963097

Exhibition schedule: Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, October 24, 2015-February 28, 2016; Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, June 19-October 9, 2016; University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, February 8-May 21, 2017.

For an art historian, two of the most rewarding moments of the research process are leafing through the dusty, faded ephemera of an archive and opening a crisp new volume of cutting-edge scholarship. These distinct pleasures converge in the Walker Art Center’s exhibition catalogue Hippie Modernism: The  Struggle for Utopia, which sports the sun-bleached binding and yellowed pages of a book that has weathered a library shelf since the 1960s. Its scholarly essays and interviews, typeset in period fonts and illustrated with black-and-white graphics, are interspersed with full-page color layouts printed on paper textured with a swirling, psychedelic surface. Deftly collaging text and images from the 1960s and 1970s into contemporary configurations, these mock-advertisements for emerald green bottles of “WOBO” (“World Bottle”) Heineken and glossy inflatable furniture invoke the fun, funky tenor of the hippie era. Yet at the same time, they bespeak the serious tensions underlying hippie countercultures: conflicts between freedom and consumerism, joy and politics, global and local, individual and community, past and present—in short, between “hippie” and “modern.”

Struggle for Utopia, which sports the sun-bleached binding and yellowed pages of a book that has weathered a library shelf since the 1960s. Its scholarly essays and interviews, typeset in period fonts and illustrated with black-and-white graphics, are interspersed with full-page color layouts printed on paper textured with a swirling, psychedelic surface. Deftly collaging text and images from the 1960s and 1970s into contemporary configurations, these mock-advertisements for emerald green bottles of “WOBO” (“World Bottle”) Heineken and glossy inflatable furniture invoke the fun, funky tenor of the hippie era. Yet at the same time, they bespeak the serious tensions underlying hippie countercultures: conflicts between freedom and consumerism, joy and politics, global and local, individual and community, past and present—in short, between “hippie” and “modern.”

Initially, the titular phrase Hippie Modernism will strike many as a contradiction in terms. The freewheeling, sensual, and spontaneous excess of the hippie lifestyle has long been regarded as the antithesis of the universal, rational ethos of modernism, which was well institutionalized by the time the hippie counterculture blossomed in the 1960s. Further, the hippie penchant for crafts and agrarian, communal living situations seems to clash with the machine-age ideal of technocratic progress. This exhibition, however, seeks to challenge such binaric thinking through its subtitle, which foregrounds the “struggle for utopia” that engaged modernists and hippies alike. In the preface and the opening essay, “The Barricade and the Dance Floor: Aesthetic Radicalism and the Counterculture,” editor and curator Andrew Blauvelt stresses the importance of moving beyond clichés of hippieism as frivolous and superficial. Blauvelt clarifies, “The hippie was and remains a highly mediated figure, one used rhetorically within this project as the same kind of empty signifier to which accreted many different agendas” (12). For Blauvelt, the hippie spirit encapsulated a broader range of positions, aesthetics, and geographies than scholars have previously considered. At the same time, Blauvelt reminds us that individual hippie circles each carried distinctive, local inflections that must be acknowledged and restored.

Balancing these macro and micro views, the essays that follow explore various approaches and sites within Blauvelt’s expanded hippie modern rubric. A number of concepts link clusters of contributions; this review seeks to highlight just a few such connections by discussing the essays thematically rather than the order they appear in the book. In “Agency and Urgency: The Medium and Its Message,” Lorraine Wild and David Karwan focus on the underground graphic design of hippie independent newspapers, concert posters, flyers, manifestos, manuals, tracts, and other printed documents. Due to their DIY production and inexpensive materials, these media were not simply overlooked in the history of design, but were often denied status as “design” at all. Nevertheless, Wild and Karwan contend that this amateur aesthetic of densely packed text, uneven typesetting, and multiple forms of illustration—including hand-drawing, photography, and collage—effectively communicated the urgency of the hippies’ social and political goals. The form of the catalogue brilliantly reimagines this style in its own fonts, layouts, and materials, allowing the reader to experience the communicative power of hippie design firsthand.

By crafting a style so well-suited to delivering polemical ideas and information in a quick, compelling fashion, hippie graphic designers fulfilled the modernist dictate of form following function. But what was the nature of their politics? Simon Sadler takes up this issue in his contribution, “Mandalas or Raised Fists? Hippie Holism, Panther Totality, and Another Modernism.” Juxtaposing the loosely articulated goals of Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalogue (1968-1972; published intermittently through 1998) with the identity-based agenda of the Black Panthers, Sadler proposes that both groups extended the modernist dream of utopian social reorganization. Yet whereas the Black Panthers perpetuated the historical avant-garde’s militaristic Leftism, Brand and his acolytes espoused a holistic approach based on gradual, organic social change. This distinction supports Blauvelt’s view, developed across the volume, that the hippies practiced a politics of agitation and refusal through their lifestyle and aesthetic rather than through organized action. In this way, they function as important intermediaries in the shift to the depoliticized, institutionalized postmodernism that came to dominate art, architecture, and design during the 1970s.

Sadler’s essay highlights the heterogeneity of the Bay Area scene, which Craig J. Peariso and Greg Castillo elaborate further in their respective contributions. In “It’s Not Easy Being Free,” Peariso introduces us to the Diggers, a collective who distributed free food and other goods as means of contesting the capitalist economy, and the Cockettes, an urban commune and drag performance troupe who defied hegemonic gender norms. Peariso is interested in how both groups deployed “freedom” as an organizing principle, but he is also attuned to the ways in which such efforts could be co-opted and commodified by the mainstream. Castillo, too, concerns himself with how hippies rejected the logic of exchange. To do so, he moves outside the Haight-Ashbury of the Diggers and Cockettes, which he regards as the center of merchandized, media-friendly hippie culture, to the environs of Berkeley and Silicon Valley—or as he puts it in his title, the “Counterculture Terroir: California’s Hippie Enterprise Zone.” Castillo’s discussion centers on a contribution to Progressive Architecture magazine, “Advertisements for a Counter-Culture,” which is reproduced in facsimile as a catalogue centerfold. “Advertisements” features an editable diagram tracing connections between major hippie groups and figures; Castillo follows this map to illuminate themes of “earth awareness,” holism, education reform, and community that circulated across Northern California, once again revealing the politics underlying hippie antics.

This region was also the birthplace of computers, and many readers will be surprised to learn the role that hippies played in the development of Silicon Valley technologies. In their essay, “How Cybernetics Connects Computing, Counterculture, and Design,” Hugh Dubberly and Paul Pangaro offer a detailed, interdisciplinary history of cybernetics, the study of biological, social, and mechanical communication and control systems. Both in writing and in the visual form of a “social graph” (128-9), Dubberly and Pangaro detail the complex interrelationships between major players in computing, counterculture, and design, including Brand, Ross Ashby, Humberto Maturana, Gordon Pask, Heinz von Foerster, and Norbert Wiener. Brand’s writings on computers in the counterculture also serve as a starting point for Felicity D. Scott. In “Networks and Apparatuses, circa 1971: Or, Hippies Meet Computers,” she argues against Brand’s optimistic belief that the values of hippie engineers were compatible with their investors’ interests. The Ant Farm collective exposes the rift between corporate and countercultural worldviews with their nationwide Truckstop Network, which Scott describes as “a multifaceted project for a mobile community that would be equipped with nomadic shelters and high-tech equipment, along with a computer-controlled network of communication interfaces, in order to inhabit America differently” (104). Scott’s fear that hippie technological experimentation may, in fact, have served the interests of the United States’ military-industrial complex recalls similar concerns over mainstream co-option raised by Peariso and Castillo.

A real contribution of the catalogue is its expanded notion of a hippie diaspora that reverberates internationally during an age of burgeoning globalism. In “Buckminster Fuller’s Reindeer Abattoir and Other Designs for the Real World,” Alison J. Clarke probes the mutual influence between the Pan-Scandinavian Design Students’ Organization (SDO) and American-based utopian architects Fuller and Victor Papanek. Appropriating mainstream media outlets, these activists urged designers to consider the impact their products might have on the world’s cultures and ecosystems. Clarke reveals the true radicality of these figures’ ideas by situating them in their Cold War context, raising issues of anticonsumerism, ecology, and systems theory that link to other essays in the catalogue. Esther Choi gives a more literal inflection to themes of accessibility and transparency in her close analysis of Viennese collective Haus-Rucker-Co’s inflatable plastic membranes, prostheses, and architectures. Titled “Atmospheres of Institutional Critique: Haus-Rucker-Co’s Pneumatic Temporality,” her essay eschews a straightforward symbolism of the enclosed sphere or bubble as a utopian symbol of containment and purity. Instead, Choi views the “soft yet pressurized logic” (33) of the group’s mutable plastic forms as a means to counter the permanence, rigidity, and closure associated with the modernist tradition and the institutions it supported.

Catharine Rossi and Ross K. Elfline both transport readers to Italy, where as Elfline reminds us, intense debates over access to urban space made it difficult—not to mention counterproductive—for activists to embrace the “back-to-the-land romance” of US hippies (144). However, this does not mean American hippie discourse did not impact Italians. Rossi’s “From East to West and Back Again: Utopianism in Italian Radical Design” explores how West-Coast Beat culture, hippie living situations, and Eastern religions were major influences on the “Radical Design” movement that flourished in Florence, Milan, and Turin from the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s. Much like the SDO featured in Clarke’s essay, Ettore Sottsass and the collectives Superstudio and Global Tools advocated designs that fill practical needs rather than invented desires. Zeroing in on Superstudio, Elfline’s essay “Radical Bodies” proposes that the Italian media perception of American hippies inspired the collective’s turn to a more hopeful, human architecture, which they realized through dematerialized architectural proposals and events. In this way, the one-dimensional hippie stereotype that the rest of the volume seeks to counteract resurfaces, but is strategically deployed by Italians to envision alternatives to their own alienated labor.

A section of eight exclusive interviews give voice to the various themes developed across the catalogue’s nine scholarly essays. Choi reprises her discussion of Haus-Rucker-Co with one of its original members, Günter Zamp Kelp, and discusses another architectural group, ONYX, with participants Woodson (“Woody”) Rainy and Ron Williams. Adam Gildar speaks with Clark Richert and Richard Kallweit about “Drop City,” an artist commune of geodesic domes. Susan Snodgrass continues the discussion of the American built environment in her interview with architect and designer Ken Isaacs. In dialogue with Gerd Stern of USCO, Tina Rivers Ryan discusses the group’s pioneering “intermedia” artwork, while Liz Glass discusses related ideas of synesthesia with sound and light artist Tony Martin. Jeffrey T. Schnapp talks experimental pedagogy with Maurice Stein, Larry Miller, and Marshall Henrichs. Finally, Blauvelt converses with Franco Raggi of Global Tools, a “Radical Design” collective promoting democratic architecture in the spirit of “access to tools,” Brand’s tagline for the Whole Earth Catalogue (425). The interview format proves to be the perfect mode for exploring these communal, collaborative projects.

From the catalogue’s mosaic of images, texts, and interviews, as well as its design, it becomes clear that there is no singular Hippie Modernism, but multiple Hippie Modernisms. This comes into even sharper focus in the section of plates, which illustrate projects by artists referenced by the preceding articles and interviews, including Sottsass, Ant Farm, Haus-Rucker-Co, Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, and Corita Kent. The plates also expand the roster—and by extension, the definition of “hippie modernism”—to include work by newly introduced figures such as Alan Shields, Lucas Samaras, Hélio Oiticica, Nancy Holt, and Robert Smithson. As with any large-scale group exhibition, one could add even more names to this list: the French Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV); Bay Area fiber artists Kay Sekimachi, Ed Rossbach, and Barbara Shawcroft; members of the New York-based Pattern and Decoration movement; or the vast number of feminist and anti-racist artists that play supporting roles in the Walker’s project. It is a strength of this exhibition that it opens onto so many unexplored avenues for further inquiry. Nor are these frontiers confined to the past; Hippie Modernism’s revolutionary reconsideration of technology, ecology, community, and activism illuminate contemporary phenomena such as social media, global warming, #blacklivesmatter, and the polarizing politics surrounding the 2016 US presidential election. By bringing together two terms once thought to be opposed, Hippie Modernism has altered the way each concept is understood in isolation, providing “access to tools” we can use today.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1551

PDF: Parrish – Hippie Modernism

About the Author(s): Sarah Parrish is a doctoral candidate in the History of Art & Architecture, Boston University.