Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios and At First Light: Two Centuries of Maine Artists, Their Homes and Studios

Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios

by Valerie A. Balint, with a foreword by Wanda M. Corn

New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2020. 256 pp.; 225 color illus. Paper: $29.95 (ISBN: 9781616897734)

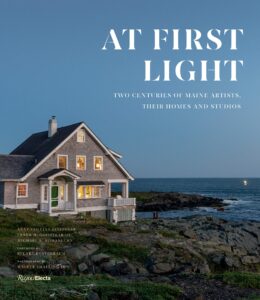

At First Light: Two Centuries of Maine Artists, Their Homes and Studios

by Anne Collins Goodyear, Frank H. Goodyear III, and Michael K. Komanecky, with a foreword by Stuart Kestenbaum and photographs by Walter Smalling Jr.

New York: Rizzoli Electa, in association with the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, ME, 2020, 240 pp., color illus. Hardcover: $55 (ISBN: 9780847867899)

Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios and At First Light: Two Centuries of Maine Artists, Their Homes and Studios were published in June 2020 and March 2020 respectively, and it initially seems that they could not have been released at a worse time. The fundamental premise of both volumes is that experiencing the environs in which an artist lived and worked enriches one’s understanding of that creative individual’s vision, influences, and working process. “To stand on the densely paint-stained floor at the Pollock-Krasner studio is a transformative experience even if you have seen Jackson Pollock’s paintings in museums hundreds of times,” writes Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios author Valerie A. Balint, arguing, “It is an experience that cannot be replicated outside of this particular place” (17–18). However, by the second quarter of 2020, the burgeoning COVID-19 pandemic had severely curtailed travel and temporarily shuttered many of the sites featured in these books. Simply put, accessing the “tangible, immersive experience” touted in the Guide was impossible (16). And yet now, after more than a year during which the line between our personal and professional lives was all but erased, we might argue that we have all gained a new appreciation of the extent to which the places where we live and work shape us and, likewise, how we shape them to suit our needs.

Occasioned by the twentieth anniversary of the Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation (HAHS), a network of independently run visual artists’ spaces in the United States, Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios is the first comprehensive publication dedicated to the program’s member sites (numbering forty-four in total at the time of printing). The volume opens with a foreword by Wanda M. Corn, founding chair of the HAHS advisory committee, who has championed the cause of preserving these historic properties for decades. In a special section of the journal American Art on artists’ homes and studios published in 2005, Corn characterizes these sites as “a special kind of archive” akin to, and arguably richer than, the scholar’s typical arsenal of primary sources (diaries, letters, scrapbooks, photographs, and the like). “By reading these work sites as material artifacts and comparing one against another, we gain insight into the history of artistic culture as well as the art and aesthetic allegiances of the artists who created and worked in these spaces,” Corn writes.1 And indeed, perhaps more so than the well-trodden homes of distinguished American writers, musicians, and political leaders, the built and natural environments of artists (for whom the visual and spatial are fundamental) hold tremendous interpretive promise.

Occasioned by the twentieth anniversary of the Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation (HAHS), a network of independently run visual artists’ spaces in the United States, Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios is the first comprehensive publication dedicated to the program’s member sites (numbering forty-four in total at the time of printing). The volume opens with a foreword by Wanda M. Corn, founding chair of the HAHS advisory committee, who has championed the cause of preserving these historic properties for decades. In a special section of the journal American Art on artists’ homes and studios published in 2005, Corn characterizes these sites as “a special kind of archive” akin to, and arguably richer than, the scholar’s typical arsenal of primary sources (diaries, letters, scrapbooks, photographs, and the like). “By reading these work sites as material artifacts and comparing one against another, we gain insight into the history of artistic culture as well as the art and aesthetic allegiances of the artists who created and worked in these spaces,” Corn writes.1 And indeed, perhaps more so than the well-trodden homes of distinguished American writers, musicians, and political leaders, the built and natural environments of artists (for whom the visual and spatial are fundamental) hold tremendous interpretive promise.

The HAHS volume describes itself as a guidebook, and its structure, content, and tone reflect this identity. The entry for each member site consists of a photograph of the artist inhabitant(s) and a quotation(s) from them about their art-making process, artistic philosophy, or relationship to place, followed by a short descriptive text accompanied by exterior and interior views of the property and, occasionally, a representative example of the artist’s work. The final paragraph of most entries highlights other noteworthy sites nearby. All HAHS member properties must be open to the public and demonstrate a commitment to preservation, but otherwise they vary quite widely. For example, some venues retain original furnishings while others do not, and some, but not all, house original works of art or archives. The properties also range in scale and utility, including the Florence Griswold House, a large, formerly bustling boarding house; the Arthur Dove/Helen Torr Cottage, a modest, functional structure with a spectacular water view; the David Ireland House, an integrated home/studio/gallery space/three-dimensional work of art in an urban center; and Frederic Church’s Olana State Historic Site and Russel Wright’s Manitoga, purpose-built properties in which architecture, interior design, and landscape were holistically conceived by their artist inhabitants. Likewise, the entry content varies, with some texts focused on specific architectural features and the material content of the spaces and others on the impact of the sites on the artists more generally.

Many entries offer novel information that enriches the readers’ picture of an artist’s working method or highlights relevant cultural networks or historical contexts. One learns, for instance, that Daniel Chester French had a railroad flatcar that could be pushed on a track installed in his studio so that he might see how various light conditions affected his sculptures. During the artist’s lifetime, the rafters in John F. Peto’s home studio supported a swing for his daughter Helen so that she could play alongside her father while he worked. George L. K. Morris sold Picasso’s classic Cubist portrait The Poet (1911; Guggenheim Museum of Art) to Peggy Guggenheim to finance building his and Suzy Frelinghuysen’s Indigenous-inspired house on the Morris family estate in the Southwest. Availing himself of the opportunity to live rent-free on the upper floor of a carriage barn in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, which was owned by a patron, Grant Wood was able to quit his teaching position and devote his full attention to painting. Georgia O’Keeffe’s restoration and customization of her home and studio in Abiquiu, New Mexico, proceeded by fits and starts due to competition for building materials with the Los Alamos National Laboratory, and the artist built a bomb shelter on her property in the 1960s.

While useful for the purposes of trip planning and visualizing geographic connections, the publication’s chronological organization by region and its “Map of Sites” lay bare the HAHS network’s uneven distribution. Less than half of the states are represented, and a significant majority of the featured properties are located in the Northeast. The paucity of locales in the South is perhaps the most conspicuous, but the middle of the country is also sparsely represented. Additionally, approximately only a quarter of the properties highlight locales associated with female artists. That said, the crucial role women played in managing these sites and/or securing their long-term preservation is a through line in the Guide. Josephine Holley, along with her husband, Edward, hosted numerous artist boarders in their Cos Cob home, while their daughter Constant Holley McRae facilitated the property’s 1957 sale to the Greenwich Historical Society. Julian Alden Weir’s daughter Cora Weir Burlingham was instrumental in preserving Weir Farm, while Daniel Chester French’s daughter Margaret French Cresson opened Chesterwood to the public in 1955 and gifted the site and collections to the National Trust in 1968. Lee Krasner provided for the long-term preservation of the Long Island home and studio she had shared with Jackson Pollock, and Corinne Melchers left the Gari Melchers Home and Studio to the state of Virginia.

To be sure, the history of American art told through these sites is incomplete. In addition to the limitations addressed above, the Guide only includes one site utilized by an artist of color: Melrose Plantation in Natchitoches, Louisiana. It was here that self-taught African American artist Clementine Hunter—notably an employee at the estate, not the owner—taught herself to paint, garnering national attention in her later years for her vignettes of local Black life. Only properties that are valued in their own time, by individuals with the resources and the wherewithal to safeguard them, survive for posterity; in her introduction, Balint concedes that the HAHS network “can represent only artistic narratives that have been preserved, and this has often excluded less-mainstream artists and diverse populations” (19). The unassuming suburban residence in Boise, Idaho, of the deaf, self-taught artist James Castle “represents an exception,” Balint writes, which is “emblematic of the modest conditions in which so many artists, both historic and contemporary, have created” (19).

Since publication of the Guide, four properties have been added to the HAHS network; notably, all were the home and studio of a woman artist, and one—the Saarinen House in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan—increases representation of the Midwest. HAHS’s printed volume is most valuable, then, when consulted in conjunction with the organization’s website, which offers regular updates on membership and programming.

The publication of At First Light also marked an anniversary—-in this case, the bicentennial of Maine statehood. A brief introduction by Anne Collins Goodyear and Frank H. Goodyear III, codirectors of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, explains that the book “celebrates the important place that the visual arts have played in the state’s history over the past two centuries,” featuring twenty-six artists “for whom Maine was or has been an important part of their lives and artistic careers” (8). The book’s entries are organized by the birthdate of the first featured artist inhabitant and range from Blue Hill’s Jonathan Fisher (1768–1847) to Rangely resident William Wegman (b. 1945). Some artists are represented by more than one Maine locale (most notably Marsden Hartley, who is linked to no less than nine different towns). Several entries focus on artist groups or pairs, including families (the Wyeths; the Porters) and couples (Marguerite and William Zorach; Rudy Burkhardt and Yvonne Jacquette). Each entry includes a likeness of the artist(s), representative artworks (typically depicting these locales and often drawn from Maine collections), and new photography of the architecture and surrounding landscape. Where the modest trim size of the Guide reflects its intended use as a travel companion, At First Light is a generously illustrated, coffee table-sized volume with plentiful striking, full-page color images.

Given At First Light’s single-state focus, geography plays a more substantial role here than in the HAHS Guide. Comparing the two publications’ entries on the Winslow Homer Studio and the Rockwell Kent/James Fitzgerald Home and Studio amplifies this subtle difference in approach; the Guide emphasizes the built environment and its effects on the lives of its inhabitants, while At First Light highlights visual relationships between the artists’ works and their natural environments. Striking interior photographs of Frank Benson’s Wooster Farm on North Haven and Lois Dodd’s home in Cushing show how these painters brought the outdoors inside through their art, adorning their walls with grand bay and forest views, while Anne Goodyear relates the “in-betweenness” of Richard Tuttle’s artwork to the location of his home on Mount Desert Island, situated “where water meets earth” (210). The influence of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, a three-hundred-acre rural campus located in central Maine, looms large among the entries devoted to living artists. Ashley Bryan came to Maine in 1946 as a member of Skowhegan’s first class, the book explains, and the school also lured David C. Driskell and Alex Katz, the latter of whom encouraged Burkhardt, Dodd, Jacquette, and Bernard Langlais to buy or build on property in the state.

At First Light closes with project photographer Walter Smalling Jr.’s anecdotal account of his 2018 road trip to document the book’s featured locales. This first-person narrative highlights the visceral experience of visiting these places. Smalling describes “fog seep[ing] into the rooms” of the Porter family home on Great Spruce Head Island on a cool summer day (234). He invokes letters John Marin wrote to Alfred Stieglitz from Carrying Place Island, lovingly complaining about the challenging conditions, and recalls his own experience at the site being bitten by mosquitoes “with a ferocity I had never before seen” (232). Smalling’s stories also alert readers that, unlike the HAHS properties, many of these historic sites are in private hands and closed to the public. Charles Herbert Woodbury’s Ogunquit home is now a vacation rental, for example, and prior to photographing the space, Smalling temporarily moved all the modern furniture out and filled it with Woodbury paintings and memorabilia loaned by the artist’s grandsons. Smalling notes that his photographs of Robert Indiana’s Vinalhaven home (a former Odd Fellows Lodge) are among the last documenting the residence and studio prior to Indiana’s death in May 2018.2 Since the book’s publication, two of the modest number of artists of color featured in At First Light—Driskell and Molly Neptune Parker—have passed away, the long-term fate of their Maine residences still in question.

The HAHS Guide and At First Light serve as sturdy jumping-off points for deeper analyses of the ways that artists’ homes and studios can enrich our understanding of their inhabitants’ lives and creative visions. Several recent publications provide models for this kind of scholarly investigation of places and possessions. In the field of literary studies, Magdalena J. Zaborowska’s Me and My House: James Baldwin’s Last Decade in France (2018) considers Baldwin’s late works through the lens of the Provençal home he inhabited for the last sixteen years of his life.3 Baldwin’s French country home was a creative incubator of sorts, Zaborowska argues, a safe space where the Black, gay, American writer hosted and exchanged ideas with a rotating cast of international artists and intellectuals. Much of Me and My House probes the compelling parallels between Baldwin’s “late-life turn to domesticity” in southern France and the “increasing focus of his works on families, female characters, and black queer home life.”4 Corn’s recent exhibition and catalogue Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern (2017) encourages art historians to consider artists’ creative existences holistically, collapsing arbitrary distinctions between art and everyday life. In this publication, Corn frames O’Keeffe’s decades-long course of modifications to her Abiquiu home and its interior decoration as an integral component of a comprehensive creative vision. The aesthetic elements that distinguish much of her artwork—simplicity, restraint, a reverence for nature—manifest themselves in O’Keeffe’s living spaces, Corn convincingly argues, and also informed the artist’s daily routines, most notably the clothes she chose to wear.5 The HAHS Guide and At First Light provide raw materials for building more scholarly narratives like these, which acknowledge the often intimate and revealing connections between what we create and the environments in which we do so.

Cite this article: Emily D. Shapiro, review of Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios, by Valerie Balint, and At First Light: Two Centuries of Maine Artists, Their Homes and Studios, by Anne Collins Goodyear, Frank H. Goodyear, and Michael K. Komanecky, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12856.

PDF: Shapiro, review of Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios and At First Light

Notes

- Wanda M. Corn, “Artists’ Homes and Studios: A Special Kind of Archive,” American Art 19, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 2. ↵

- In August 2020, the nonprofit Star of Hope Foundation, the sole beneficiary of Indiana’s estate, completed a year-long campaign aimed at stabilizing the deteriorating 1870s structure. The June 2021 settlement of a lengthy legal battle between the Star of Hope Foundation and the Morgan Art Foundation, which represented Indiana for more than twenty-five years and holds the copyright for much of his work, paved the way for Star of Hope to begin planning for the building’s long-term use. See “Historic Landmark Re-emerges, Following Major Stabilization Effort,” Courier Gazette (Rockland, ME), August 17, 2021, https://knox.villagesoup.com/2020/08/17/historic-landmark-re-emerges-following-major-stabilization-effort-1867789, and Bob Keyes, “Star of Hope, the Vinalhaven Home of Late Artist Robert Indiana, Gets New Life,” Portland Press Herald, March 21, 2021, accessed August 30, 2021, https://www.pressherald.com/2021/03/21/star-of-hope-the-vinalhaven-home-of-late-artist-robert-indiana-gets-new-life. ↵

- A companion digital exhibition organized by the author in collaboration with the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture features photographs of and personal belongings from Baldwin’s now-demolished property. See “Chez Baldwin,” accessed July 5, 2021, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/exhibitions/chez-baldwin. ↵

- Magdalena J. Zaborowska, Me and My House: James Baldwin’s Last Decade in France (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 134. ↵

- Wanda M. Corn, Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern (New York: DelMonico Books / Prestel, 2017). Another invaluable source for art-historical analysis of O’Keeffe’s New Mexico homes is Barbara Buhler Lynes and Agapita Judy Lopez, Georgia O’Keeffe and Her Houses: Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu (New York: Abrams, in association with the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, 2012). ↵

About the Author(s): Emily D. Shapiro is Managing Editor of the Archives of American Art Journal at the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution