Historical Memory, Reconciliation, and the Shaping of the Postbellum Landscape: The Civil War Monuments of Forest Park, St. Louis

St. Louis was not immune to what Erika Doss has termed “statue mania,”1 the frenzy of monument building that engulfed the United States in the decades after the Civil War. Public art played a vital role as a reunited country grappled with how to heal the deep wounds caused by the divisive conflict and forge a new national history and identity.

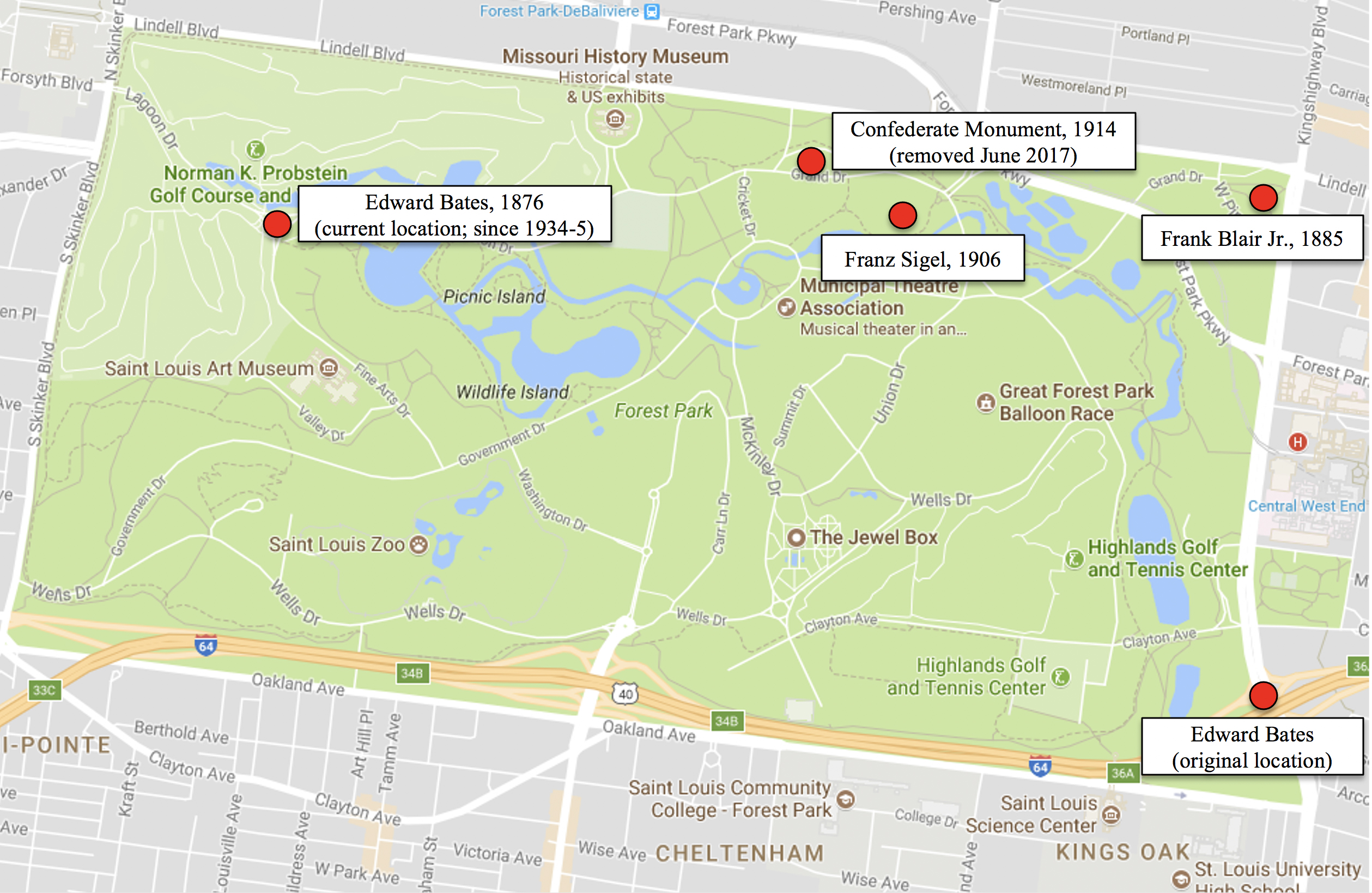

Forest Park contains the most significant public statement of Civil War memory in St. Louis. Four monuments honoring individuals from this turbulent period were erected between the park’s founding in 1876 and the entry of the United States into World War I. They celebrate Edward Bates, Lincoln’s attorney general (1876; fig.1); Frank Blair Jr., a fiercely Unionist politician and supporter of Lincoln (1885; fig. 2); German-born Union general Franz Sigel (1906; fig. 3); and the soldiers and sailors of the Confederacy (1914; fig. 4).2 In June 2017, following protracted public controversy, this group of monuments was reduced by one with the removal of the Confederate Monument.3

In his influential essay, “The Modern Cult of Monuments,” Alois Reigl argued that a monument is “erected for the specific purpose of keeping single human deeds or events (or a combination thereof) alive in the minds of future generations.”4 Not explicitly stated by Reigl, however, is that a monument’s ideological function is largely indistinguishable from its commemorative one. Through its choice of subject, be it a person or historical event, a public monument claims to assert the broader values, aspirations, and ideals of a community, city, or sometimes even a nation, at a certain time and place. It promotes a carefully constructed narrative, shaped by an individual or individuals with a distinct agenda and point of view.

The four monuments in Forest Park commemorating Civil War-era individuals were erected over the course of five decades that were some of the most consequential in United States history. Their installation was effectively bracketed by the end of Reconstruction (1877) and the fiftieth anniversary reunion of the Blue and the Gray at Gettysburg (1913), a ceremony overseen by President Woodrow Wilson, the first Southerner to assume the presidency in the aftermath of the Civil War. These decades witnessed passionate debate with regard to the shape of Civil War memory as the nation struggled to cement which version of the conflict’s history would endure, with public monuments playing a significant role in constructing and disseminating that history.5

Public monuments are now such a standard feature of our contemporary landscape that they are often overlooked. In antebellum America, however, public monuments were relatively rare. Initially there was resistance to their erection, owing to a close association with European monarchical precedents, a general Puritanical antagonism to graven images, and the belief that a monument could not adequately capture “true memory,” among other factors.6 In the aftermath of the Civil War, however, monuments began to proliferate. As Erika Doss, Kirk Savage, Michele Bogart, and other prominent scholars of public art have discussed, in the last decades of the nineteenth century, an unprecedented wave of commemoration began to transform public spaces.7

According to Savage, the uncertainty and anxiety born of this traumatic national conflict provided a fertile environment in which public monuments proliferated because patrons recognized their usefulness for shaping history into what they perceived as “its rightful pattern.”8 Designed to inspire reverence and emulation, the monuments erected in the years following the Civil War satisfied a national yearning for historical closure by celebrating the shared American ideals and values of patriotism, heroism, and moral and civic virtue, however fictional.

The four monuments erected in Forest Park exemplify the ways in which competing constituencies in St. Louis participated in debates over reconciliation and reunion. They represent significant shifts in ideas about patriotism and the role of Missouri in the Civil War and US history, raising critical questions about how and in what form the presence of these monuments kept that history alive in Forest Park. Who were these people deemed worthy of emulation and raised up on pedestals? And what were their deeds that merited remembering by the generations that followed? Equally important to consider: who were the individuals responsible for these commissions and, by extension, for shaping the public memory of the conflict? How did their perspectives and intentions inform the subjects chosen and the lessons taught? No coordinated program of installation existed in Forest Park, and the four distinct commissioning groups did not try to establish a unified visual statement or meaning. And yet, when viewed collectively, these monuments—and the ceremonies surrounding them—offer significant insight into the changing views and attitudes of the St. Louis citizenry with regard to sectional reconciliation, illuminating the shifting memories and evolving history of the Civil War in Missouri and the political, social, and cultural implications of the bloody and divisive conflict.9

Civil War St. Louis and Statue Mania

Missouri was a fiercely divided border state in the years leading up to the Civil War, a status that led it to be claimed by both the Union and the Confederacy, complete with competing governors and governments. It supplied troops to both armies, and a number of families had sons fighting on both sides of the conflict: roughly thirty thousand Missourians fought in the Confederate Army, and one hundred thousand in the Union Army. Missouri also witnessed more than one thousand battles and skirmishes during the course of the conflict, the third largest number of engagements in any state.

St. Louis, a city at the crossroads of the conflict, would remain a pro-Union and Republican stronghold for the duration of the war, owing in large part to the surge of German immigration in the preceding decades.10 Significant Confederate support also existed, especially among the city’s elites. A sizeable percentage of the white, native-born population of Missouri had Southern roots, originating from states south of the Mason-Dixon line, most prominently Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and North Carolina. In addition, even those opposed to secession were not a monolithic group. Many rejected the idea of emancipation and retained sympathy for their Southern brethren, while simultaneously remaining loyal to the Union. The success of the Unionist movement in Missouri was therefore largely due to individuals such as Edward Bates and Frank Blair Jr., two of the men whose bronze likenesses are atop pedestals in Forest Park. Both Bates and Blair understood the inherent fragility of their pro-Union coalition and the compromise required to keep it from splintering apart.11 The legacy of these internal conflicts influenced the public spaces—and the public monuments—of St. Louis for decades after the war’s last shot was fired in 1865.

Even before the conclusion of the war, new memorial traditions began to reshape the commemorative landscape in Missouri as throughout the rest of the United States. There were concerted efforts by federal and state governments, as well as local communities and private individuals, to recognize the war dead. These actions ranged from inaugurating the tradition of Decoration or Memorial Day in the years immediately after the war (1866 to 1868) to the creation of a series of permanent national cemeteries—including St. Louis’s Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in 1863—to the erection of public monuments honoring common soldiers alongside celebrated leaders throughout the North and South.

Initially, these monuments were largely funerary in nature and located in cemeteries. However, by the 1870s, the decade during which the first monument (to Edward Bates) was installed in Forest Park, a decisive shift had occurred. The individuals and events of the Civil War era were now more publicly commemorated, in civic spaces that citizens would encounter on a daily basis: in town squares, along city streets, on courthouse lawns, and in front of municipal buildings. As a result, these monuments began to take on a more celebratory cast, shifting from funereal iconography (such as obelisks) to embrace more heraldic and militaristic imagery.12

The shift toward a more celebratory message was a direct outgrowth of the national emphasis placed on sectional reconciliation, something that the Compromise of 1877, which formally ended Reconstruction, signaled was of the highest priority for the country. The loosening of federal control over the postbellum South signaled a new era in sectional relations for many white Americans, along with a growing acceptance of a romanticized version of the war, one given credence via the pageantry staged at Gettysburg, among other Civil War sites, and cities, including St. Louis. This recasting of the conflict in terms of American brotherhood and nation building offered a path toward reconciliation, but it was one reliant, in part, on forgetting, denial, or both, and characterized by debate.13

In Missouri, the immediate postwar period had seen the rise of the Radical Republicans and the implementation of their progressive agenda. However, the passage of a new state constitution in 1865—commonly referred to as the Drake Constitution, owing to its primary champion, Charles D. Drake, one of the most uncompromising of the Radical Republicans in the Missouri General Assembly—led to the fracturing of the Republican Party. This schism ultimately would result in the decades-long domination of statewide politics by the largely pro-Southern and segregationist Democrats.

The flash point for this political sea change in Missouri was the so-called Ironclad Oath, a key provision of the Drake Constitution. It targeted those who had been disloyal to the Union, stripping them of many of their rights, including the vote, a stipulation that even some of the fiercest Union defenders in the state, Blair among them, found excessively punitive. The oath’s repeal in 1870, and the subsequent re-enfranchisement of former Confederates and Southern partisans, returned to prominence and elected office many of the men Drake had hoped to permanently exclude from political life in Missouri.14 It set the stage for the rewriting of the public memory of the war by the newly empowered Democratic Party and its supporters, a shift reflected in both the monuments of Forest Park and the ceremonies surrounding their installations.

During the last decades of the nineteenth century, monument building was increasingly perceived to be an integral part of the “healthy process of sectional reconciliation,” facilitating the South’s reentry into the national mainstream.15 However, this national healing was, in the words of Kirk Savage, “a process that everyone knew and no one said was for and between whites.”16 As David Blight asserts, “the forces of reconciliation overwhelmed the emancipationist vision,” and what constituted sectional harmony became increasingly defined by the white supremacist memory of the conflict, exacting a great cost on the African American population.17

A critical distinction must be made with regard to the processes of reunion and reconciliation, as observed by Caroline Janney. Janney argues that while reunion was achieved with the legal and political reunification of Union and Confederate states immediately following the war, the process of reconciliation was more contested, drawn out, and difficult to define, with little agreement about what it meant or what shape it might take.18 And yet amid resistance to reconciliation on both sides, Savage argues that a “massive and deliberate process of collective forgetting took place” in postbellum America, aided in no small part by the extremely successful commemorative campaign engineered by the South.19

Former Confederates and their descendants possessed tremendous anxiety about what shape Civil War memory might take in the ensuing decades, and public monuments became a highly visible way for Southerners to propagate their history of the war, known as the Lost Cause. In this alternate history of the Civil War, slavery was systematically erased as a cause of the conflict, and the war was reframed as one of Northern aggression, with the heroic and victimized South positioned as the great defender of states’ rights and the Constitution.20

Citizens of the former Confederate states readily accepted this Lost Cause history, and its vindication of the Confederacy, as authoritative. It also would go unchallenged by many former champions of the Union cause—in St. Louis and elsewhere—who became complicit in this revisionism, all in the interest of national unity and healing. By the early years of the twentieth century, the public performance of fraternalism via Blue-Gray battlefield reunions, coupled with grand pronouncements concerning national unity, suggested the dissipation of sectional discord. However, this type of reconciliation-based pageantry belied a persistent refusal on both sides to grapple with the dissonance of accepting the war’s outcome while also maintaining their own distinct memory of the war. This acceptance of a romanticized and fictionalized version of the war, one fueled in large part by a conscious ignoring of the country’s painful past and the continuing legacy of slavery therefore paved the way for the segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement of the Jim Crow era. These policies endured virtually unchecked for decades throughout the South, as well as in some former border states, Missouri among them, from the 1870s, until the emergence of the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Lost Cause is preserved today through Confederate veterans’ organizations, holidays, and celebrations. Above all it lives on through the monuments that dot the landscape of both Southern and Northern states—even free states that abolished slavery decades before the Civil War—as well as those on the border that were slave-holding but sided with the Union during the war, such as Missouri.21 Public monuments, such as those in Forest Park, gain legitimacy and power from the sheer fact of their existence in shared spaces, and the belief that to be erected, there must be a consensus (whether or not one actually existed) that the subject is worthy of remembrance and that the history recorded is an authoritative one. In doing so, they offer an almost unparalleled opportunity for a small group of people, usually those with power, to publicly advance a selective and often romanticized version of the historical past.22 Through monument construction, the guardians of Confederate memory were able to significantly shape and control the history of the Civil War in public spaces throughout the United States. Therefore, while the Confederacy lost the war, those who sought to preserve its legacy and safeguard the privileges of white supremacy were extraordinarily successful, as was made clear by the passionate defense of St. Louis’s Confederate Monument mounted during the years-long debate over its removal.

What, then, were the consequences of the postbellum push for reconciliation via monument building in St. Louis, and how are the monuments of Forest Park representative of the situation throughout the United States? What does reconciliation mean today with regard to the public spaces these monuments occupy, to the history that was carefully constructed and celebrated by their original patrons, and finally, to the stories, voices, and memories that have been left out of this version of the past? Of the four monuments in Forest Park, the Confederate Monument most clearly took advantage of, and helped shape the reconciliation version of Civil War history in St. Louis, a history that purported to offer a path toward reconciliation for the entire nation. Its whitewashing of the realities at the root of the conflict, however, also ensured its failure and, eventually, its removal.

As a group, the monuments of Forest Park connected to Civil War memory—three dedicated to men whose loyalty lay with the Union, but two of whom were sympathetic to their Southern brethren, alongside one honoring the “heroes” of the Confederacy—offer a valuable opportunity to address these questions. In acknowledging both sides of the conflict in one prominent civic space, these monuments occupy the intersection of postbellum commemoration and reconciliation, illuminating the successes but also the limits and failures of the push for national unity in the aftermath of the Civil War.

The Civil War Monuments of Forest Park

Forest Park (fig. 5), founded in 1876, remains one of the largest urban parks in the United States; at 1,371 acres, it is more than 500 acres greater than Central Park in New York City. Despite a city budget stretched thin during the park’s early years, sculptural embellishment was a priority for the city commissioner of parks. In keeping with the ideals of the City Beautiful urban planning movement, which espoused the aesthetic and educational virtues of decorating public spaces with sculpted monuments, wealthy St. Louisans were strongly encouraged to contribute to the beautification of the city’s most prominent civic space. Eugene F. Weigel, the first commissioner of parks (1877–86), attempted to attract sculptural donations but had little success. In 1896, Commissioner Franklin L. Ridgely (1895–1902) implored St. Louis elites to donate “fountains, bridges, statuary, monuments, etc.”23

As Martha Norkunas has noted in her evaluation of the public monuments of Lowell, Massachusetts, monuments are often erected in public spaces that have no immediate connection to the individual or event being commemorated. Instead, there are “key sites in every city where citizens compete for the right to assert their identity and power.”24 In the decades following its opening, Forest Park became one of those key sites for St. Louis. Even before the 1904 World’s Fair, the park had become a popular recreation destination for those looking to escape the dirty, crowded streets of the downtown area. By 1896, Forest Park was attracting an average of more than two and a half million visitors per year.25

While the park itself is not significant in terms of the history of the Civil War in St. Louis, it was a logical choice for any group wishing to publicly commemorate individuals connected to the conflict, as it guaranteed high visibility and a wide audience for any monument, and that monument’s message.

The Monument to Edward Bates

The first monument to be placed in Forest Park was dedicated to Edward Bates (1793–1869), a moderate Republican who had served as Lincoln’s attorney general from 1861 to 1864. Commissioned in 1871 by the Bates Monument Association (BMA), it also was the first monument commemorating a prominent Civil War-era figure to be erected in the city of St. Louis. Despite St. Louis being a pro-Union stronghold during the war and largely receptive to the agenda of the Radical Republicans in the years immediately following, with the Bates Monument, the emergent public history of the conflict was one that privileged moderate voices. These voices suggested an easier and even inevitable path toward national reconciliation, rather than one that was complicated and fraught.

The Bates statue was originally intended for another of the city’s earliest public green spaces, Lafayette Park.26 When the BMA, under the direction of President Charles Gibson, proved unable to raise the full $11,000 owed to sculptor James Wilson Alexander MacDonald (1824–1908) for the completed sculpture, the commission languished.27 In 1876, the BMA succeeded in securing the remaining balance of $3,000 via the Forest Park Commissioners, the administrative body that oversaw the park until stewardship was transferred to the St. Louis commissioner of parks in 1877. The monument was installed prominently “on the highest knoll” just inside the southeastern entrance to the park, at the intersection of Kingshighway Boulevard and Clayton Road (now Clayton Avenue), two of the city’s main thoroughfares, with a “commanding prominence from all directions” (fig. 6).28 In the 1930s, it was moved to its current location on the opposite side of the park, near the northwestern entrance, to accommodate highway construction.29

The bronze figure of Bates is positioned atop a red granite pedestal adorned with four bronze portrait medallions of contemporary Missourians who had personal and political connections to the former attorney general. Bates is dressed in contemporary clothes and standing in a relaxed contrapposto, his determined gaze fixed outward into the surrounding landscape (fig. 7). In his left hand, he holds a partially open book, which he rests on an eagle-shaped stand emblazoned with the Great Seal of Missouri. This detail, combined with his serious, authoritative demeanor and extended right hand, suggests that Bates is in the midst of addressing a courtroom audience, presumably a nod to his storied law career and his years as attorney general and member of the famed “team of rivals” in Lincoln’s cabinet, alongside William Seward and Salmon Chase (Bates also served as the first attorney general of Missouri).

MacDonald, an Ohio native who made St. Louis his home at an early age, spent his antebellum years in the newspaper business while simultaneously establishing himself as an accomplished marble carver. It was during the postwar period that MacDonald, by then based in New York City, developed a national reputation on the strength of his bronze portrait commissions, which included both busts and larger scale statues of a variety of famous Americans, such as William Cullen Bryant, Washington Irving, and General Armstrong Custer.30 Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, bronze became the medium of choice for public sculpture, due not only to its greater durability and tensile strength, but also owing to its symbolic value. With the development of specialized bronze casting foundries and equipment in the United States, the decision to employ bronze was in part a patriotic one, with American sculptors proclaiming their artistic independence from Europe through their proficiency in the medium.31

The Bates statue was completed during the most successful decade of MacDonald’s career, which was also a peak period for bronze statues of military and political heroes in the United States. MacDonald’s skill with bronze is most evident in the sensitive modeling of Bates’s face. His exploitation of the textural variations made possible by the medium resulted in what one local newspaper praised as a “correct likeness”32 of the aged statesman, including his prominent crow’s feet and ample beard. The wrinkled brow, tightly pursed lips, and direct stare also convey a seriousness befitting its august subject, typical of the simple and direct naturalism that characterized MacDonald’s mature work.

By the time of his death, Edward Bates was a widely respected, nationally known figure, one of the “great men” of Missouri’s history and therefore deemed worthy of sculptural commemoration. In contrast to the three monuments that would follow, there is no explanatory text on the Bates Monument, no enumerating of his deeds, no indication of why he is raised on a pedestal. The sole identifying inscription, located on the front of the base, simply reads: “Bates.” Given Bates’s local and national fame, this is not surprising, as Missourians were very familiar with the accomplishments of this devoted public servant who reliably represented the interests of their “border state” in the years leading up to and during the Civil War.

As attorney general, Bates fought doggedly for the preservation of the Union. However, a Southerner by birth and a former slave owner, he also warned of the dangers of disenfranchising his Southern brethren, providing a crucial counterweight to the Radical Republicans in Lincoln’s cabinet. In addition, while three of Bates’s sons fought on the side of the Union—and his youngest was a cadet at West Point during the war—a fourth son, Fleming, served in the Confederate army. The Bates family personally experienced the consequences wrought by the bitter sectional conflict, agonizing divisions known to many Missouri families.33

Emphasizing the monument’s connection to Missouri Civil War history, each of the four men commemorated in the bronze portrait medallion reliefs not only had a link to Bates but also a key role to play in the conflict.34 On the monument’s north face is Hamilton Gamble (1798–1864), Bates’s brother-in-law and law partner, who served as the Union governor of Missouri during much of the Civil War era (from 1861 to 1864). His steadfast advocacy in defense of the Union was shared by his nephew, Charles Gibson (1829–1915), depicted on the west face, who occupied the office of solicitor general during Bates’s tenure as attorney general. James Eads (1820–1887; fig. 8), the famed civil engineer and inventor, adorns the east face. On the advice of Bates, President Lincoln enlisted Eads to spearhead the Union defense efforts on the Mississippi River, and he would construct the first US Navy ironclads in his St. Louis shipyard. Finally, Henry Geyer (1790–1859), who occupies the south face, was a lawyer and US senator from Missouri from 1851 to 1857, best remembered as the assistant legal counsel to the slave-owning defendant, John Sanford, in the famed Dred Scott case (1857), one of the most controversial decisions in the history of the Supreme Court and a precipitating event leading to the Civil War.35

Geyer held the most strongly pro-Southern and pro-slavery views of all of the men honored on the monument. And yet, like Bates and his three companions, Geyer also embraced a conciliatory approach to the sectional conflict, eschewing the strident condemnation and punitive measures favored by the Radical Republicans who dominated Missouri politics in the years directly following the war’s conclusion. Gibson would eventually resign his post as solicitor general over his belief that the Lincoln administration had too heartily embraced the Radical Republican agenda. Eads held strong anti-slavery and emancipationist views, and he, along with several other prominent St. Louisans, had written to Lincoln prior to his inauguration urging him to choose a secretary of state from a slaveholding state, specifically Bates, in an effort to forestall secession (Lincoln would ignore this advice in favor of William Seward).36

The monument, hailed as the “great and distinguishing feature of Forest Park,”37 was unveiled on the park’s opening day, June 24, 1876, less than five months before the contested presidential election of 1876 that would result in the end of Reconstruction. The ceremonies surrounding the monument unveiling offer insight into the political climate of the time, not only in St. Louis but nationally, as they also served as a dedication for the opening of the park overall. This, along with the fact that the Democratic National Convention was being held simultaneously in St. Louis, meant that the festivities were larger and more extensive than a typical monument unveiling, and it affected not only turnout but also the makeup of the crowd, which was striking in the number of Southern sympathizers who gathered to honor a proud Unionist and prominent member of Lincoln’s cabinet.

The Democratic governor of Missouri, Charles Henry Hardin (1875–77), and president of the Forest Park commissioners, Andrew McKinley (1874–77), were among the first to address the crowd of an estimated forty to fifty thousand attendees, praising the city and people of St. Louis and the newly opened park. The unveiling occurred just three days before the Democratic Convention was to be held in St. Louis, and several of the speakers were also convention delegates, including then–lieutenant governor of New York, William Dorsheimer, a former Republican who had served under General John C. Fremont in his Missouri campaign but switched his party allegiance following the war.

Mayor Henry Overstolz (1876–81), the first native-born German to be elected to city office in St. Louis, oversaw the unveiling ceremonies, completed by Minnie Holliday, daughter of a prominent St. Louis family. In his remarks, Overstolz praised Bates, “the illustrious statesman and jurist,” as a “model for the young men of all succeeding times.”38 Montgomery Blair, former postmaster general under Lincoln (and brother of Frank), and former Senator James Rood Doolittle of Wisconsin, both good friends of Bates and strong supporters of President Lincoln, also gave speeches. They, too, were former Republicans recently converted to the Democratic Party, underscoring the tumultuous and shifting nature of political allegiances during these decades. Doolittle praised Bates for his honest character and his patriotism, specifically the key role he played in the preservation of the Union as a member of Lincoln’s cabinet. Bates was a man who “stood by the helm of state, and by his faith, and courage, and good sense sustained and strengthened the hands of the President in the most trying hour of our country’s history,” a moment that “seemed to threaten to bring about the prayers of the despots of the old world that the Union should be destroyed and the flag of the stars and stripes to sink out of sight forever.”39 Mirroring the moderate tenor of the monument itself, the ceremony highlighted Bates’s identity as a committed patriot and public servant. His devotion to the preservation of the Union was worthy of emulation by Americans on both sides of the political divide, as was made clear by the speakers who themselves reflected the fluidity of allegiances that was a feature of Missouri politics in the postwar years.

The Monument to Frank Blair Jr.

Erected in 1885, the monument dedicated to Frank Blair Jr. (1821–1875), like the Bates statue before it, celebrates a man who was a staunch and vocal proponent of the preservation of the Union, one who believed that national unity must take precedence over sectional interests. Blair advocated for and represented a conciliatory approach to postwar relations between North and South, even switching his party affiliation from Republican to Democrat in 1866 owing to his vehement opposition to Reconstruction. The former soldier and lifelong politician is commemorated in a way that emphatically frames his Unionist devotion in terms of the larger national narrative of reunion taking shape during these years.

The Frank Blair Monument Association (FBMA) was founded in October 1879, but initial efforts to erect a monument stalled after the committee rejected seven proposals for lacking “sufficient merit.”40 A second call for proposals in 1881 resulted in the selection of Wellington W. Gardner, a little-known local sculptor who had received his training at Washington University in St. Louis.41 In 1883, after considering the two other prominent parks in the city—Lafayette Park and Tower Grove Park—the FBMA selected a location at the northeast entrance to Forest Park (fig. 9). The site guaranteed high visibility, as one of the city’s railway lines stopped nearby just outside the park boundary, and the extension of streetcar lines to the park in 1885 would make the location even more favorable (the landscape surrounding the monument has since been altered slightly in order to accommodate modern traffic needs).42 Commissioner of Parks Weigel assured the group that he would “gladly appropriate any suitable ground that may be asked for,” an eagerness born not only of the strong desire to embellish the park, but also indicative of the cachet Blair possessed in St. Louis.43

Blair, like his friend Bates, is represented by a bronze statue perched atop a high granite plinth. The figure, praised by contemporaries as a perfect likeness —including his characteristic “heavy mustache”—stands in a naturalistic pose with his left leg slightly forward, projecting determination and confidence.44 The furrowed brow and deep-set eyes communicate the impassioned orator’s well-known intensity and fiery nature, particularly in defense of the Union. Blair dominated Missouri politics in the decades surrounding the Civil War, first as owner and editor of the staunchly pro-Union Daily Missouri Democrat newspaper and later as a member of the House of Representatives. He was an especially fierce champion of then-candidate Lincoln, passionately campaigning on behalf of the future president throughout the country. He grips a scroll in his left hand while raising his right arm in a clenched fist, as he appears to address an unseen crowd (fig. 10).

Despite his distinguished military service under General Ulysses S. Grant and General William Tecumseh Sherman, Blair is depicted as a civilian, wearing a suit rather than his Union army uniform. However, the lengthy and effusive inscription (fig. 11) emblazoned on the back of the pedestal highlights Blair’s military valor as an essential aspect of his worthiness for commemoration. He is to be remembered as “the creator of the first volunteer Union army in the South; the saviour of the state from secession; the patriotic citizen-soldier, who fought from the beginning to the end of the war.”45 The materials used to cast the sculpture also subtly acknowledge Blair’s military record, as in April 1880, Congress approved the secretary of war to deliver “twelve condemned bronze cannon” to the FBMA, to be used “for the purpose of aiding in the erection of a monument to the late Major-General Francis P. Blair, junior.”46

Blair was born in Lexington, Kentucky, the youngest son of a prominent, politically connected family. His father was a close ally of President Andrew Jackson, and his brother Montgomery would achieve national recognition serving as supporting counsel to Dred Scott in his 1857 Supreme Court case; he would also serve as postmaster general under Lincoln.47 In the mid-1850s, Blair’s embrace of the newly formed Republican Party, and his subsequent courting of the German immigrant population in St. Louis, where he practiced law with his brother, made him an essential part of the party’s growth and success and a dominant force in Missouri politics. However, following the Civil War, Blair found himself increasingly estranged from his party, largely due to his emphatic opposition to the disenfranchisement of former Confederates. His strong anti-Reconstructionist—and by extension pro-reconciliation—views were at odds with the Radical Republicans then on the rise in the state.

Despite identifying publicly as an anti-slavery politician, Blair’s rhetoric was strikingly similar to that of his segregationist brethren in Missouri and throughout the country, who argued for the inherent racial superiority of white men. Like Bates, Blair had once owned slaves but also had opposed the extension of slavery into the new territories. He advocated for gradual emancipation while he was in Congress, but only if it was followed by repatriation to Africa, a position he also shared with Bates and other fellow moderate Republicans. Furthermore, Blair was vehement in his refusal to support the granting of citizenship rights to African Americans. Blair believed that emancipation would negatively affect white men, asserting in starkly racist terms that “freed blacks hold a place in this country which cannot be maintained. Those who have fled to the North are most unwelcome visitors. The strong repugnance of the free white laborer to be yoked with the negro refugee, breeds an enmity between races, which must end in the expulsion of the latter.”48

His white supremacist views led Blair to abandon the Republican Party in 1868 to run for vice president on the Democratic ticket alongside Horatio Seymour. He blamed Republicans for allowing the South to be ruled by “a semi-barbarous race of blacks who are worshipers of fetishes and polygamists” and who desired the subjugation of “white women to their unbridled lust.”49 Blair embraced a campaign of vicious racial animus, promoting the idea that, once elected, Democrats would return whites to power in the South and in doing so help preserve the “purity, beauty and vigor of our own race.”50 Following Seymour and Blair’s electoral loss to the latter’s former army commander Ulysses S. Grant, Blair returned to Missouri. In 1871, he was elected to the US Senate, his final political office, making the elimination of voting restrictions on former Confederates a chief legislative priority, as well as helping thwart legislation aimed at reining in the power of the Ku Klux Klan, then in its infancy.51

These “conciliatory” efforts on behalf of former Confederates and their sympathizers are given prominent placement in the monument’s inscription right alongside Blair’s Unionist devotion, both viewed as equally valid reasons to honor him. As the monument’s inscription makes clear, Blair’s identity as “herald and standard bearer of freedom in Missouri” was not viewed as incompatible with that of the “magnanimous statesman, who as soon as the war was over, breasted the torrent of proscription, to restore to citizenship the disenfranchised Southern people.” In fact, Blair’s outspoken desire that national unity not come at the expense of white citizens in the South perhaps explains, in part, the choice of civilian dress (over his soldier’s uniform) and the overall subtlety of the statue’s martial and Unionist elements.

On May 21, 1885, Peter Foy, the newly elected president of the FBMA and Blair family friend,52 presented the monument to Mayor David R. Francis (1885–1889) who had declared a citywide holiday for its unveiling and dedication. According to local newspaper reports, close to fifteen thousand people attended the dedication, a testament to what a beloved figure Blair was in St. Louis. Blair’s daughter, Christine Graham, was asked to lift the American flag that veiled the monument and preside over the elaborate ceremonies as a whole. These included a military parade featuring a large contingent of Union veterans marching in tribute, a thirteen-gun salute, and a series of laudatory speeches by another of Blair’s former commanding officers, General Sherman, among others.53 The Union hero offered this praise of Blair: “[He] did more than any single man to hold this great central city of our Union to her faithful allegiance to the General Government, so necessary to the perpetuity of the Union.”54 And former Illinois Governor Gustav Koerner, himself a German immigrant and, like Blair, a staunch supporter of Lincoln, highlighted Blair’s military leadership of the Germans in Missouri and his fight to keep the state in the Union.55

In the decade since the installation of the Bates Monument, Missouri politics had shifted decisively, with Democrats assuming legislative control and a number of former Confederates elected to statewide office. Reflective of this realignment of Missouri politics in the post-Reconstruction era and echoing the conciliatory tenor of the monument’s inscription, sharing the platform with Sherman and Koerner was Governor John Marmaduke (1885–1887). The former major-general in the Confederate army also spoke in praise of Blair, providing a fitting tribute to the man who had fought tirelessly for re-enfranchisement of former Confederates like himself and whose actions had ultimately paved the way for Marmaduke’s election to the governorship. In addition, among those participating in the parade were not only members of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), the largest and most powerful of the Union veterans organizations, but also representatives of the Southern Historical and Benevolent Society, which invited “all ex-Confederates to join the association and be present in body.”56 With the commemoration of Frank Blair, twenty years after the war’s conclusion, the language of reconciliation had become more prominent, both on the monument itself and in the celebration surrounding it. In addition, as David Blight notes, the voices calling for reconciliation had begun to mix with those of the segregationists, a merging of the two strains of memory that would reach its apex in the early 1900s.57

The Monument to Franz Sigel

The third monument to commemorate a Civil War-era figure in Forest Park was dedicated on June 24, 1906 (fig. 12). The equestrian monument, dedicated to German-born Union general Franz Sigel (1834–1902), was the first statue installed after the significant reshaping of the park precipitated by the 1904 World’s Fair. It was located in a highly trafficked area, close to the recently restored Music Pagoda (built 1876), a popular site for band concerts. The monument honors not only Sigel but all of the German Americans who fought to preserve the Union. It is the first monument in the United States to honor this group’s military service during the Civil War.58 Although it is Sigel alone on top of the pedestal (fig. 13), the monument’s inscription (on the north side of the base) pointedly celebrates the common soldiers’ contributions and sacrifices: “To remind future generations of the heroism of German American patriots of St. Louis and vicinity in the Civil War of 1861 to 1865,” it reads, with “General Franz Sigel” carved below (fig. 14).

The monument was commissioned by the Franz Sigel Monument Association (FSMA), which formed in September 1902. The membership included representatives of both the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), the powerful Union veterans association, and the Turnverein, the influential German social societies that played a significant role in the public life of St. Louis during these decades.59 The FMSA, under the direction of Leo Rassieur, a prominent judge in St. Louis as well as a former Commander-in-chief of the GAR (1900–1901), began to raise money from German Americans throughout the country to fund the monument immediately following Sigel’s death.60 Fittingly, German sculptor Robert Cauer (1863–1947) was chosen to sculpt the monument, and the bronze statue of Sigel was cast in Lauchhammer, Germany. Cauer was a member of a prominent artistic family, and he completed several projects in St. Louis, including a second monument in Forest Park dedicated to another celebrated German, Friedrich Jahn, in 1913.61

Sigel is depicted in battle dress astride his horse on a high granite plinth ringed with a laurel wreath design. Cauer, a sought-after portrait sculptor, captured both a convincing likeness of Sigel (modeled after photographs of the general) and the distinct personalities of both horse and rider. The former Union general leans forward and to the side, field glasses in hand, with an expression of intense concentration on his face. He appears in the midst of scouting the surrounding landscape for enemy troops. Sigel’s horse is likewise alert, lending the sculpture a sense of immediacy and potential movement. Its four hooves are firmly planted, and its ears are perked up in shared surveillance, ready to respond to its master’s commands.

According to reporting by the Cassville Republican newspaper, Sigel is depicted at the moment of one of his greatest victories, when he rallied the German troops at the Battle of Pea Ridge to overcome what looked to be a certain defeat for the Union army.62 A preliminary design for the monument, recorded in the Missouri Sharp Shooter (fig. 15), included more emphatically martial content, with additional battle scenes carved on the sides of the pedestal. A bronze figure of a flag-waving Union soldier was to be positioned prominently at ground level beneath Sigel, perhaps a visual representation of the German soldiers honored in the completed monument’s inscription.63 Although it is unclear how seriously this proposal was considered, if built as described, the monument, the first in the park to explicitly celebrate a soldier, would project a pointedly sectional message, something that the FSMA may have felt wise to downplay given the political climate of Missouri at that time.64

Historically, the equestrian monument was the standard choice for representing military heroes, an image of commanding authority linked to the ancient Roman Empire and great leaders such as Marcus Aurelius. Although less ubiquitous than the standing soldier type, the equestrian form would proliferate in the decades following the Civil War, becoming omnipresent in the American memorial landscape. The Sigel equestrian monument—the first erected in St. Louis—announces the Union commander’s dominance on the battlefield. Rather than represent the general as victorious, Cauer embraced a “caught in the moment” realism that aligns Sigel with the depictions of Bates and Blair already installed in the park.

While the ability to erect monuments in public spaces is most often connected to power and wealth and thus reserved for the elite, certain ethnic groups have had great success with monument building campaigns at specific points in history. Martha Norkunas has observed that this success is most often achieved when the aims of the ethnic group in question align with the dominant ideology.65 The Sigel monument is a prime example of this phenomenon. It illustrates how the German immigrant population, the largest ethnic group in St. Louis during the second half of the nineteenth century, was able to claim civic power, identity, and a prominent public voice through monument building. These were attained, in part, through sheer numbers, but then amplified by the crucial role German Americans had played in defending and preserving the Union.

Franz Sigel was one of the so-called “Forty-Eighters,” supporters of the failed German Revolution of 1848 to 1849, many of whom immigrated to the United States in its aftermath to escape retribution. Although trained to serve in the government militia, Sigel was swept up in revolutionary fervor and joined the insurgent army in Baden in 1848. When the uprising was defeated, Sigel fled Germany, ultimately arriving in New York in 1852, before moving his family to Missouri in 1857.66

Like the majority of German immigrants, especially the strongly anti-slavery Forty-Eighters, Sigel was pro-Union and a supporter of the nascent Republican Party, which had rightly sensed that Germans could be persuaded to support their platform.67 When the Civil War began, Germans—now firmly in the Republican camp—were eager to support their newly adopted country, and many volunteered for the Union army. Sigel’s military experience in Germany led to his being given command of the 3rd Missouri Union forces, a regiment of mostly German American volunteers. Sigel was exceedingly popular with his countrymen, whose numbers had swelled in St. Louis during the decades just before the war. This made him a valuable asset to the Union cause in the eyes of President Lincoln, who, throughout the war, remained a staunch defender of Sigel, well aware of the enormous political influence Sigel wielded with the German American community.

Following some initial successes in the early years of the war and a promotion to major general, Sigel’s military record and reputation took a decidedly downward turn as the conflict stretched on. Following several significant defeats, Sigel was relieved of command in July 1864; however, his turbulent service record did little to dampen enthusiasm for the commander among the German American population. They continued to view their service under Sigel with undiminished pride, pledging their loyalty to the general long after the conclusion of the war and his military fall from grace, proclaiming: “we fight mit Sigel.”68 The installation of the monument in Forest Park offered the opportunity for German Americans to publicly rehabilitate their hero. They employed the language of the equestrian tradition to burnish Sigel’s military reputation, commemorating his efforts for the Union in triumphant terms, a victory not just for him but for all German Americans.

The 1906 dedication ceremony of the Sigel Monument celebrated his service to the Union while simultaneously underscoring his German identity, as it prominently featured speeches and songs in his native tongue. Hundreds of Civil War veterans representing every GAR post in the city participated in the parade to the monument. Many were German American, including a group of soldiers who had served under Sigel and had no doubt helped raise the funds for the monument. As president of the FSMA, Judge Rassieur presided over the celebration, offering words of praise as he presented the monument to City Commissioner of Parks Robert Aull (1903–6). Rassieur’s daughter, Cora, was given the honor of pulling the cord to unveil the monument as the band played “America the Beautiful.”69

Monuments to Union men with strong ties to the German community, including Sigel and Blair, were a key part of the annual St. Louis Memorial Day celebrations orchestrated by members of the GAR, the Women’s Auxiliary, and other Union veterans organizations. The fact that the Sigel statue unveiling ceremony, and later ceremonies involving the monument, were couched in the language of nationalist devotion and honored the German American population at large, not solely the general, aligns with the postwar acknowledgment of the group’s importance to St. Louis and to the nation at large.70

In contrast to those of Bates and Blair, the monument dedicated to Sigel represents a commemorative shift in Forest Park. It was the first to recognize common men alongside the illustrious one whose likeness was raised on the pedestal, and it was also the first to honor the Union in explicitly militaristic terms. And yet, Sigel’s martial identity did not preclude his serving as a strong symbol of the sanctity of national unity. He was representative of a “brothers in arms” mentality that had only grown stronger in the wake of the Spanish-American War (1898). This short-lived conflict nevertheless had a profound effect on sectional reconciliation efforts, uniting, in the words of then-Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, “the sons of the men who wore the blue and of those who wore the gray” against a common foe.71

As Gail Bederman posits in Manliness and Civilization, her examination of the intersection of race and gender at the turn of the twentieth century, Roosevelt celebrated a very specific—and racially limited—heroic nationalism, one that claimed “not only a personal power for himself but also a collective imperialistic manhood for the white American race.”72 As a German, Sigel fit the prescribed image of white, Anglo-Saxon heroism praised and embodied by Roosevelt, and thus he was an ideal figurehead for the reconciliationist history that was its byproduct. Although former Confederates did not play a significant role in the Sigel ceremonies (in contrast to those surrounding the Blair Monument), several Confederate veterans donated funds to FSMA for the completion of the statue, most prominently Joseph Boyce, vice president of the St. Louis City Council and a former captain in the Confederate Army.73 These donations indicate the potency of a Civil War history that is one of shared sacrifice, bravery, and patriotic devotion on both sides of the conflict. It is the advancement of this narrative—that honor and respect is owed to one’s fellow soldiers, regardless of allegiance—that helped to forge a path toward the final Civil War monument in Forest Park, then in its planning stages.

The Confederate Monument

Until its removal in the summer of 2017, the Sigel equestrian statue’s closest sculptural neighbor was the only monument in Forest Park to celebrate the Confederacy.74 Just as the Sigel Monument celebrates the collective contributions of German Americans, the Confederate Monument also honored the sacrifices of common soldiers, although in this case, they were the soldiers and sailors of the Confederacy, not those fighting to preserve the Union. According to the St. Louis Star, the location of the Confederate Monument was chosen because of its centrality in the popular park and because it was “one of the parts most frequented” (fig. 16).75 The placement meant that the two most explicitly partisan monuments in the park were placed in dialogue, facing each other across Grand Drive, one of the main northern thoroughfares within Forest Park.

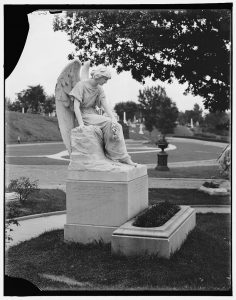

Beyond the subject it commemorates, the form of the Confederate Monument also distinguishes it from the previous three monuments. The conceit of the solitary bronze figure atop a pedestal that characterizes the Bates, Blair, and Sigel Monuments was replaced by a thirty-foot-high modified obelisk with a large bronze narrative relief panel depicting an unidentified Southern family sending a young man off to war (fig. 17). Carved into the upper portion of the granite shaft is a low-relief figure of an angel (fig. 18) representing the spirit of the South floating protectively over the family, “inspiring its men to deeds of bravery.”76 A dedicatory inscription at the base of the monument (fig. 19) states that it was: “Erected in the memory of the soldiers and sailors of the Confederate States by the United Daughters of the Confederacy of Saint Louis.”77

The choice to employ a form derived from the obelisk can be understood within the larger context of nineteenth-century funerary practices, allowing the United Daughters of the Confederacy to more easily characterize their commission as memorial in nature. During the postwar period, significant numbers of these space-saving, comparatively cost-efficient, and durable monuments, prized for their connection to one of the greatest civilizations of antiquity, were erected in cemeteries throughout the North and the South to commemorate the war dead on both sides of the conflict.78

The overall design of the St. Louis monument is ascribed to George Julian Zolnay (1863–1949), a Hungarian-born sculptor and one-time professor at Washington University in St. Louis.79 He was assisted by the prominent St. Louis architect Wilbur Tyson Trueblood, a colleague of Zolnay’s at Washington University, who lent his expertise to the construction of the granite shaft.80 Zolnay was celebrated in Southern circles owing to his sculptures for the Jefferson Davis family plot at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, completed between 1899 and 1911, and was responsible for numerous other Confederate commissions.81

The installation of the Confederate Monument in Forest Park in 1914, nearly fifty years after the conclusion of the war whose veterans it purported to honor, is reflective of the spike in Confederate commissions that occurred in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, as the Jim Crow era of legalized segregation flourished in the wake of the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision (fig. 20).82 Its addition to the commemorative landscape of St. Louis seemingly suggests that a new era of reunion was afoot in the city, that a public consensus had been reached concerning the history of the war and who was worthy of remembrance.

And yet, the controversy surrounding the Confederate Monument that culminated in its removal in June 2017 was not the first time it was at the center of heated public debate. Anxieties regarding Confederate commemoration in the city were evident from the earliest days of the monument’s conception, notably with regard to its placement in a public park (rather than a cemetery). It is the only monument in Forest Park to have required the passage of a city ordinance authorizing its construction (approved December 16, 1912), following an initial rejection by the St. Louis City Council and protracted controversy over its design.83

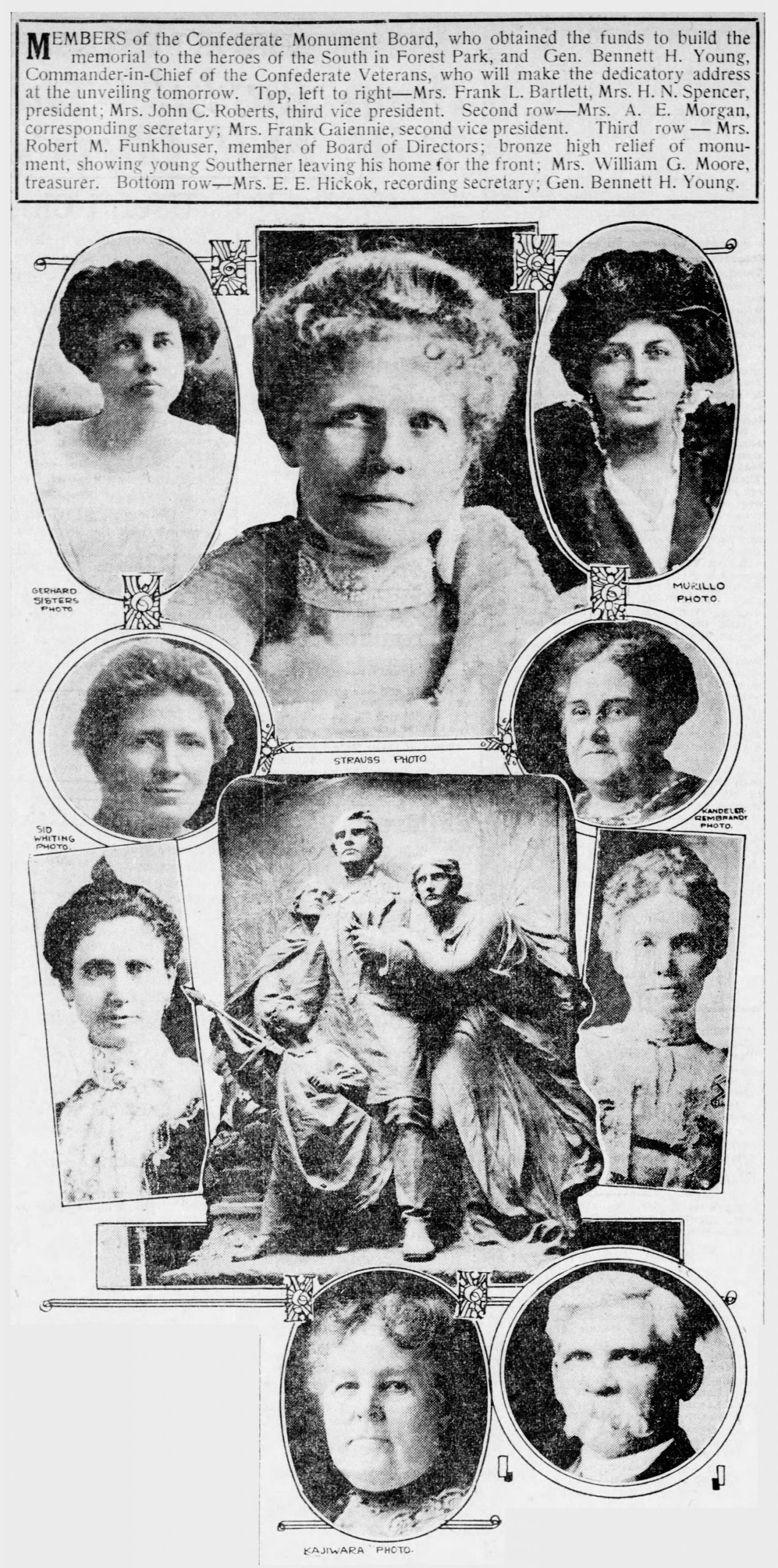

That the Confederate Monument is included as part of the Civil War history told by the monuments of Forest Park is a tribute to the extraordinarily savvy efforts of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), and, in particular, the Ladies’ Confederate Monument Association (LCMA), which was composed of members of the three principal St. Louis chapters of the UDC.84 Discussions about a monument date back to 1897, but it was not until March 1905 that the LCMA (fig. 21) was organized and tasked with the express purpose of raising the $23,000 (about a half a million dollars today) necessary to erect a statue in Forest Park.85

The UDC, founded in 1894, arguably became the most effective purveyor of Lost Cause ideology, with monument building an essential piece of their strategy of instruction and dissemination, particularly in the years leading up to World War I. As Karen L. Cox and others have noted, Southern women were the driving force behind much of the postwar Confederate commemoration, proving to be incredibly effective in gaining support for their monuments, using their gender to appear above the political fray. Monument construction enabled nineteenth- and early twentieth-century middle-class women to enter the public sphere and claim public power in an acceptable way, maintaining their traditional role as keepers of Southern memory, honoring their men, and safeguarding their heritage. Although St. Louis was a city of strong Unionist fervor during the Civil War, a significant portion of the population was allegiant to the Confederate cause. Southern sympathies endured in the years following the war, allowing the UDC to play an active role in the public life of the city during the early decades of the twentieth century.86

Additionally, the UDC was instrumental in shifting the terms of reconciliation to more directly align with their white supremacist version of Civil War memory, one that vindicated the Confederacy and those who fought for it as patriots and heroes. The war veterans could indulge in the “Blue-Gray gush” of pageantry and fraternalism that was increasingly the male experience of reconciliation. The United Daughters would steadfastly resist the reconciliationist impulse—that is, until the nation was ready to accept reconciliation as defined by the terms they dictated.87

In 1912, having raised a significant amount of the needed funds for the monument, the LCMA sponsored a design competition.88 Prior to the final committee selection, the designs of the three finalists—George Julian Zolnay, Robert P. Bringhurst, and Frederick W. Ruckstuhl—were publicly exhibited. Soon thereafter, Ruckstuhl sent a letter to Mrs. A. E. Morgan, secretary of the LCMA, asking for Zolnay’s elimination from the competition on the grounds that his design violated the terms of the competition, which explicitly stated there could be “no figure of a Confederate soldier, or object of modern warfare.”89

The UDC decision to include this design requirement was couched in terms of uniqueness, of not wanting a “conventional soldier’s monument of the sort which can be seen at nearly every county seat, both in the South and in the North.” They, however, simultaneously acknowledged that “they wished to avoid any possibility of arousing antagonism,”90 a charge that Ruckstuhl leveled against his fellow sculptor. Zolnay responded to Ruckstuhl’s objections with an unsparing critique of his fellow sculptor’s design, while fervently defending his own, arguing that the instructions may have expressly forbidden the use of a soldier, but “they contained nothing prohibiting martial character, such as every monument to the heroes of the Civil War must bear.” Nevertheless, while the sculptor proclaimed his design “the best thing he had ever done, and the best thing he ever would do,” he vowed to leave it up to the LCMA to decide whether “his design had not fulfilled their conditions.”91

Despite Ruckstuhl’s objections, the LCMA selected Zolnay’s design for the monument, concurring with a Post-Dispatch writer who concluded that the male figure was “a potential soldier though not yet an actual one.”92 The organization, however, ran into further opposition in November 1912, when members of the St. Louis City Council voted down their proposal, in part because Zolnay’s design prominently featured the Confederate flag, held by the child in the foreground. Councilman William Protzmann, one of the “no” votes, defended his action as a conciliatory one, stating: “I feel it would be flaunting the Confederate flag in the face of the Union men to authorize the erection of this monument in Forest Park. It would be opening an old wound.” President John Gundlach nonetheless expressed surprise that “any sectional feeling” remained in St. Louis.93

An editorial appearing in the Post-Dispatch less than a week after the vote argued for the acceptance of the monument as a gesture of tolerance, goodwill, and magnanimity toward the “nearly one-half” of St. Louisans possessing Southern roots and sympathies. The writer then continued: “The other half is made up mostly of persons with sufficient intelligence, breadth of mind and human sympathy to realize that the issues of the Civil War are settled forever, to forget all animosities of the past and to view the heroisms of the North and South as the common glorious heritage of the reunited American people.”94 After all, as one anonymous St. Louisan claimed in his letter to the editor (in reference to the monuments to Blair and Sigel already in the park): “Surely if the ex-rebels can stand for these, the ex-Federals would be reciprocally polite towards a more symbolic figure of the Confederacy.”95

LCMA board member Mrs. Robert M. (Alice) Funkhouser condemned the city council decision, calling the opposition “the height of narrow-mindedness” and “totally un-American.”96 Despite Funkhouser’s assurances that St. Louisans were “generous and open-minded” of spirit, many did not support a Confederate statue, regardless of design. Dr. F. W. Groffman, speaking on behalf of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (SUVCW), proclaimed that “the Confederacy is a lost cause, and we feel that those who supported it should abandon it. There is talk of a united country, no North, no South, but in some parts of the South there is even objection to placing the US flag on school buildings, and we are opposed to permitting those people to place a monument commemorating an attack on the Government in our public parks.”97

Groffman’s comments echoed earlier sentiments by James Dobyne, then commander of the St. Louis GAR Ransom post (no. 131), who during the planning phase of the monument declared: “If it is to be a monument of the brave deeds of the Confederate soldiers, I can see no objection to it. If it is to be erected as a monument to the ‘Lost Cause,’ I can see no reason for it.”98 Dobyne’s comments illustrate the near impossibility of creating a neutral monument to honor the common Southern soldier, as to erect a monument—especially in a public park—praising their brave deeds and stripped of the context of slavery was to erect a monument to the Lost Cause.

Thomas B. Rodgers, a representative for the Missouri division of the GAR, also issued a statement on behalf of the powerful Union veterans group, indicating that the organization believed that the cemetery at Jefferson Barracks would be a more suitable location for the monument. He reminded readers that the GAR had always supported honoring the Confederate dead, but that “this monument seems to be to the Confederate cause rather than to the Confederate dead, and there is a distinction.” And yet, despite the obvious discomfort regarding the monument, Rodgers also assured readers that “while we may doubt the propriety of placing a monument in a public park in St. Louis, which never was a Confederate city, we shall probably say nothing about it,”99 signaling that the GAR would allow the forces of reconciliation, unity, and by extension, the Lost Cause to rule the day.100

A Post-Dispatch editorial titled “Will St. Louis Offend Southerners?” published on December 3, 1912, ultimately appears to have turned the tide decisively in favor of the monument. The writer reminded readers of the importance of Southern trade and warned of the economic consequences that might accompany the rejection of the LCMA request and the appearance of having “no sympathy for Southern sufferings.”101 On December 6, a new vote was held by the city council, and the monument project overwhelmingly passed, nine to two. Councilmen William Edward Caulfield, who was absent for the first vote, and Henry Rower, who originally had voted “no” due to the presence of the Confederate flag, both later confessed that the editorial and its warning of possible offense to Southern businessmen had greatly influenced their affirmative votes.102

On May 25, 1913, less than six months after the affirmative city council vote, St. Louis hosted a parade billed as a “final reunion of the Confederate and Union Veterans of the Civil War,” an event that underscores the potency of the reconciliationist forces that, in part, helped make the Confederate Monument a reality. Staged in honor of Memorial Day, the festivities were designed to “cement the friendship” between the two groups. They serve as a prime example of the type of pageantry that had become increasingly common in the decade leading up to the fiftieth anniversary of the war, as the symbols and rituals of reconciliation proliferated and Blue-Gray reunions, both large and small, were staged throughout the country.

To visually underscore the spirit of unity, shared sacrifice, and service, the parade began with the former Confederates marching in front before the order was reversed, allowing Union soldiers to appear at the head. In his address to the crowd, Captain W. R. Hodges of the GAR stated: “Since Missouri was the scene of the embitterment of brothers and fathers and sons, it is the fitting place to start the annual reunion celebration, which will extend throughout the country.”103

At the same time that this idealized vision of peaceful, white brotherhood was being celebrated, race relations in St. Louis were growing increasingly fraught. In 1916, the city voters overwhelmingly approved a segregation ordinance by a three-to-one margin that prohibited anyone moving to a block with a population 75 percent of more of another race. And just across the Mississippi River in East St. Louis, Illinois, rising racial tensions reached a breaking point in early July 1917. An ongoing labor dispute between striking white workers and the black migrants brought in by employers to cross picket lines resulted in race riots considered to be among the most brutal episodes of racial violence in the first decades of the twentieth century.104

Like the Memorial Day celebration, both the design of the Confederate Monument and ceremonies surrounding its installation offered a highly romanticized version of the Civil War, stripped of any the divisiveness and rancor that characterized the actual conflict. Its indebtedness and fidelity to the tenets of the Lost Cause is made clear through its iconography and overall form, as well as the two inscriptions that adorn its reverse side. The prominent inclusion of female figures in the relief of the Southern family mirrors the narratives on a number of other UDC commissioned monuments, including the UDC’s only national monument, the Confederate Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery (fig. 22), which was unveiled on June 4, 1914, six months prior to the Forest Park monument. The UDC and other Lost Cause devotees viewed the Arlington memorial, as well as the ceremonies surrounding its installation, as their greatest triumph.105 Alongside the graves of the victorious Union dead, the UDC had succeeded in erecting a monument honoring states’ rights and denying slavery as the cause of the war, a monument heralded as patriotic, as an “emblem of a reunited people,” in the words of President Wilson, who spoke at the unveiling.106

One of the chief Lost Cause contentions, widely disseminated by the UDC through their monuments, was that the war had been fought to defend the Southern family. By highlighting the sacrifices made by women and children, their defense of the homestead, and the Southern way of life, while simultaneously downplaying the military angle, the monuments celebrated the Confederacy in a way that was difficult to publicly refute. As Nina Silber has argued, home and family were rallying points that both those in the North and South could agree on; therefore, this focus on the domestic assisted the “collective forgetting” that Kirk Savage describes. Those in the North could more easily accept and sympathize with the Southern plight when it centered on the familial repercussions of the war, notably when women (the UDC) were the ones making this argument.107

Annette Stott’s evaluation of the Thiele Family Monument in Union Cemetery, Milwaukee—specifically the representation of the matriarch, Johanna, as an angelic figure—also suggests a reading of the spirit of the South figure that augments the gendered message of Zolnay’s relief. Angels were common features in Gilded Age cemeteries.108 Stott, however, asserts that Johanna is depicted as the “angel in the house,” a widely popular conception of ideal womanhood in late nineteenth-century America, and one directly connected to selfless and self-sacrificing domesticity, the exact virtues that the women represented on the Forest Park monument are meant to embody.109 Additionally, the presence of a heavenly messenger floating above the Southern family was surely designed to recall Zolnay’s most celebrated work, the funerary ensemble for the Jefferson Davis family at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond. On top of the monument dedicated to Davis’s daughter, Varina Anne “Winnie” Davis (1899; fig. 23) perches an angel, eyes downcast and clutching a garland of poppies, a fitting tribute to the original Daughter of the Confederacy, an exemplar of Southern womanhood, devotion, and sacrifice.110

The memorial connotations of an angelic figure, especially one carved into a granite obelisk, may have been designed to mask, to a certain extent, the heroic and celebratory message of the Confederate Monument. However, the monument’s imposing size, its use of classical motifs, and its prominent placement within the city’s busiest public park, belies its memorial purpose and reveals the Lost Cause ideology at the heart of the commission, as do the inscriptions on its reverse side (fig. 24).

The first inscription, positioned at eye level, quotes General Robert E. Lee, the embodiment of Confederate heroics and a key figure in the propagation of the Lost Cause: “We had sacred principles to maintain and rights to defend for which we were in duty bound to do our best, even if we perished in the endeavor.”111 The second, lengthier inscription covers much of the reverse face of the obelisk and is courtesy of Virginia native and St. Louis transplant Robert Catlett Cave, a minister, author, and Confederate veteran. Cave was the author of Defending the Southern Confederacy: The Men in Grey (1911), a book that the UDC and other Confederate sympathizers celebrated for its role in “setting the historical record straight” through its propagation of critical pieces of the Lost Cause mythology. Cave roundly dismissed slavery as the primary impetus for secession, and indeed, his words on the monument pay tribute to the Confederate soldiers’ actions in defense of states’ rights and their fight for independence from tyranny—akin to the nation’s forefathers—praising their “sublime self-sacrifice” and “purest patriotism,” with nary a mention of slavery.112

The dedication ceremony for the Confederate Monument was held on December 5, 1914, with the hallmarks of a Lost Cause celebration on full display.113 It was not the first ceremonial event held in honor of the monument. On September 23, 1914, a Confederate flag-waving captain, Robert McCulloch, whose wife, Emma, was then president of the Confederate Dames chapter (no. 1225) of the Missouri UDC, led a procession to Forest Park to celebrate the laying of the monument’s cornerstone. He was accompanied by fellow members of the UCV as well as representatives of the three UDC chapters then active in St. Louis (fig. 25).114 The two chapters of the Children of the Confederacy based in the city, the Robert E. Lee and Betty S. Robert chapters, also played prominent roles in the parade and festivities that followed. This inclusion of representatives of the Confederate children’s groups for monument-related ceremonies was a typical practice aimed at impressing upon the next generation that they were now entrusted with the caretaking of these key Confederate traditions and “truths.”115

For the December ceremony, a crowd of around five hundred was in attendance (fig. 26). Although this was a comparatively smaller number than was present for the monument ceremonies previously held in the park, the gathering included civic leaders; Emil Tolkacz, the city’s director of public works, standing in for Mayor Henry Kiel (1913–1925); and national figures. Bennett H. Young, commander-in-chief of the UCV, gave the dedicatory address, paying special tribute to the sacrifices Missourians had made for the Confederate cause.116 General Seymour Stewart, commander-in-chief of the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), who had also spoken at the September cornerstone laying, then applauded the noble and heroic efforts of the Confederate soldiers, couching his praise in the language of family and home while highlighting the crucial contributions made by Southern women during the war, as was standard for UDC-hosted unveilings. To conclude, Mary Fairfax Childs recited her original poem, “The Boys Who Wore the Gray,” before the crowd paraded to the site of the monument itself. Alexander H. Major Jr. and Dean McDavid, the presidents of the Lee and Robert chapters of the Children of the Confederacy, respectively, unveiled the monument as the band played “Dixie” and the crowd cheered. The celebration concluded with remarks by Zolnay and Elizabeth Spencer, president of the LCMA. Spencer praised Missouri, “so strongly Southern in sentiment,” as a fitting location for a monument, recounting “the story of tearful women. . . . not holding back their loved ones, but rather encouraging them to do their duty . . . let it ever stand as a tribute of the unfailing love and devotion of the women of the South.”117

Like the three monuments that preceded it in the park, the Confederate Monument offers a visual barometer of the drive for reconciliation that took hold in the postbellum United States, one that had steadily gained traction over the course of the four decades since the installation of the Bates Monument. While it is possible that the UDC could have erected a monument in St. Louis prior to 1914, it seems likely that temporal distance was key to the commission’s ultimate success, as anxieties about Confederate commemoration could be met with arguments that, fifty years later, all sectional feeling had dissipated and the commission was solely memorial in nature. The Confederate Monument was approved by the city council only once it was framed in those terms, with its militaristic and partisan message muted and the focus squarely placed on the home front and patriotic sacrifice. Ultimately, it was this distance from the war, and the restrictions imposed during the commissioning process, chiefly with regard to iconographic choices, that not only allowed the monument to be constructed but helped to obfuscate its true ideological message for years to follow, publicly perpetuating a fictional consensus about Civil War memory in St. Louis.

The Limits and Future of Reconciliation

The Confederate Monument escaped popular notice for just over a century, blending into the larger commemorative landscape of St. Louis. Unnoticed that is, until April 2015, when Mayor Francis Slay announced the need to “reappraise” it.118 Slay’s decision to revisit the monument occurred amid the outrage and heightened racial tensions resulting from the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014 and the increased attention placed on Slay’s administration by the “Black Lives Matter” movement. The mayor’s call to action appeared tragically prescient when, less than two months later, on June 17, 2015, nine parishioners at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, were killed by an avowed white supremacist who embraced Confederate symbols. The following week, the Forest Park monument was one of a number of Confederate monuments to be vandalized in cities ranging from Richmond to Baltimore to Austin.119

Slay’s invitation to debate the future of the Forest Park monument was met with mixed reactions from the public. Many were surprised to learn that such a monument existed in St. Louis, even those who viewed it on a regular basis, having never gotten close enough to read the inscriptions—although those, by design, could be mistaken as simply honoring the brave sacrifices of common soldiers. Others were enthusiastic about the prospect of ridding the city of what they viewed as a racist monument. Still more argued that any removal effort would be an attempt to whitewash history, the first stop on a slippery slope leading to large-scale historical revisionism and the erasure of other historical figures, potentially even the censure of founding fathers owing to their slaveholding pasts. Some of the most enthusiastic protestors labeled the prospect of removal Orwellian, fascist, and Taliban-esque.120

In December 2015, a committee of business and civic leaders appointed to evaluate the monument concluded its work, recommending removal. The Request for Proposals (RFP) regarding the re-siting of the monument that had circulated in September 2015 was met with deafening silence. The Missouri Civil War Museum was the sole cultural institution in St. Louis to submit a proposal, subsequently rejected by the committee because it declined to address plans for future interpretation and exhibition of the monument, a key requirement of the RFP.121

After Lyda Krewson was elected mayor of St. Louis in April 2017, the removal of the monument from Forest Park became a top priority for her administration. Debate about its future reached a fever pitch in May, following the removal of four Confederate monuments in New Orleans. In early June, owing to renewed instances of vandalism and numerous protests, a fifty-foot perimeter was installed around the monument, and the city initiated a plan for its removal. Only then did the UDC claim full, legal title to the monument, subsequently transferring that ownership to the aforementioned Missouri Civil War Museum.122 The city appeared ready to contest the actions of the UDC, but the parties ultimately reached an agreement for removal that stipulates that the monument cannot be displayed publicly in either St. Louis city or county and, in addition, must be located in one of three types of spaces: a Civil War Museum, a Civil War battlefield, or a Civil War cemetery.123