Telling Imperfect Histories with the Digital

PDF: Van Horn, Telling Imperfect Stories

A note at the beginning of the digital catalogue for the Library Company of Philadelphia’s exhibition Imperfect History: Curating the Graphic Arts Collection at Benjamin Franklin’s Public Library alerts readers that the “unprecedented public health crisis, the concurrent 2020 Black Lives Matter and social justice protests, as well as the January 2021 insurrection at the United States Capitol need to be acknowledged as contributing influences on the works included.”1 Indeed. In many ways, the digital catalogue and digital exhibition that accompany the in-person Imperfect History exhibition document a process of institutional soul-searching and acknowledgment of the need for systemic change that was accelerated by the racial reckoning at museums, libraries, archives, and heritage centers.2 As they have prioritized social justice and sought greater inclusivity and equity, many institutions have redirected collecting priorities, reevaluated cataloging practices, and even reconsidered their missions, hiring practices, and work environments. These shifts have also involved a new transparency about, and critical assessment of, institutional histories and past curatorial aims and practices.3

For the Library Company of Philadelphia’s graphic arts department, that history is both a long one, beginning in 1731 with Benjamin Franklin’s founding of the library, and a comparatively short one, starting in 1971 with the creation of a separately curated collection of popular visual materials. Conceived in response to the department’s fiftieth anniversary, Imperfect History is a microhistory of a research collection that now encompasses approximately one hundred thousand works on paper, prints, photographs, and ephemera from the sixteenth through the early twentieth centuries. Far from hagiographic, Imperfect History’s institutional critique and critical reflections on the role of the curator, as well as the responsibilities of any viewer of graphic materials, will resonate widely. That reach is heightened by the project’s significant digital components. While the Library Company mounted an exhibition, printed a catalogue, and hosted a visual literacy workshop, they also created a multifaceted digital experience funded in large part by the Henry Luce Foundation.4 This material includes the digital exhibition and digital catalogue as well as a virtual symposium and exhibition opening, supplemented with numerous blog and social-media posts, in addition to a curatorial fellowship.

The hybrid nature of Imperfect History is indelibly shaped by the cultural moments of 2020–21 and the virtual modes of public engagement necessitated by the pandemic. However, while engineered for an emergency, this two-pronged solution provides lasting benefits. The digital components of Imperfect History are not subsidiary to their physical counterparts and, indeed, are more robust than the exhibition’s footprint allowed, enabling the curators to increase the exhibition’s impact and accessibility by reaching a broader audience for a longer period. This review takes the digital exhibition and digital catalogue on their own merits.

As a digital exhibition, Imperfect History is visually gripping, easy to navigate, and offers opportunities for close looking. After clicking to enlarge an image, a digital tool reminiscent of a magnifying glass’s round lens allows viewers to zoom in to better see the object’s surface, as well as any stains, holes, and tears. In the introductory section, the lens enables readers to peer closely at a series of photographs of the Library Company (c. 1880 to c. 1960) to follow the curators’ prompt: “What is visible and hidden in these views of the people, materials, and spaces that comprise the history of the Library Company of Philadelphia?” This magnifying lens motif also structures the exhibition’s title graphic (fig. 1), which features a series of details from collection materials that are presented in round circles, as if encountered through a telescope or magnifying glass. This graphic captures both the episodic glimpses into the collection that Imperfect History offers and the curators’ injunction to look carefully and critically.

Beyond recording an institutional history, Imperfect History has two primary concerns. The first is visual literacy: the idea that graphic materials are a form of evidence that have to be situated in historical contexts of making and viewing in order to be understood fully. While the concept of visual literacy will not be surprising for art historians, it is important for those unaccustomed to interacting critically with visual materials. The digital exhibition prepares viewers to recognize visual artifacts’ significant potential for producing histories, a function directly related to the Graphic Arts Department’s location within a research library.

Imperfect History’s second major focus is on curatorial practice. The digital exhibition highlights and demystifies the role of the graphic-arts curator in developing and interpreting a collection. The exhibition performs a doubled movement: interpreting the selected works but also calling attention to their curation, past and present. Imperfect History thus offers a self-reflective, frank, and engaging look at the curatorial process. Sometimes curators dislike objects they curate, as explored in the wonderfully named section “What Curators Love to Hate and Hate to Love.”5 Sometimes curators flub up; a blog post discusses accidentally giving a researcher the wrong answer about archival holdings.6 The most laudable aspects of the digital exhibition, however, are the exposition of past curatorial practices and priorities that cumulatively enacted white supremacy and the attention paid to diversifying and problematizing a white-centered graphic archive, a trajectory that Imperfect History advances.7

As conceived by Library Company curators Sarah Weatherwax and Erika Piola, joined by then-curatorial intern Kinaya Hassane, the digital catalogue and digital exhibition hinge on the term “imperfect.” “Imperfect” indicates a critical stance that connects the materiality of visual artifacts to acts of viewing and collecting in the past, as well as to histories of gendered and racialized institutional bias and, more broadly, to the impact of positionality. As the concept is developed across the six sections of the digital exhibition, “imperfect” acknowledges the racism and sexism that shaped Philadelphia’s visual past. This is evident in the racially stereotyped imagery on a nineteenth-century trade card or an eighteenth-century hand-colored engraving of Jamaican John Richardson Primrose Bobey. Bobey suffered from vitiligo and was exhibited in an anatomy museum founded by the Philadelphia-born Dr. Thomas Pole, who donated the print in 1790. Representation in the print collection was also “imperfect” in relation to the Philadelphia communities surrounding the Library Company. The term suggests the relative paucity of Black and women artists and subjects included in the collection as well as the demographics of those employed by the Library Company and the roles women and people of color were allowed to assume. “Imperfect” also marks artifacts that exhibit signs of damage or loss, errors in printing, or even fakes. And, finally, the term points to the recognition that the questions curators and visitors bring to visual materials are themselves “imperfect,” conditioned by the viewer’s positionality and by the social and cultural concerns of the moment.8

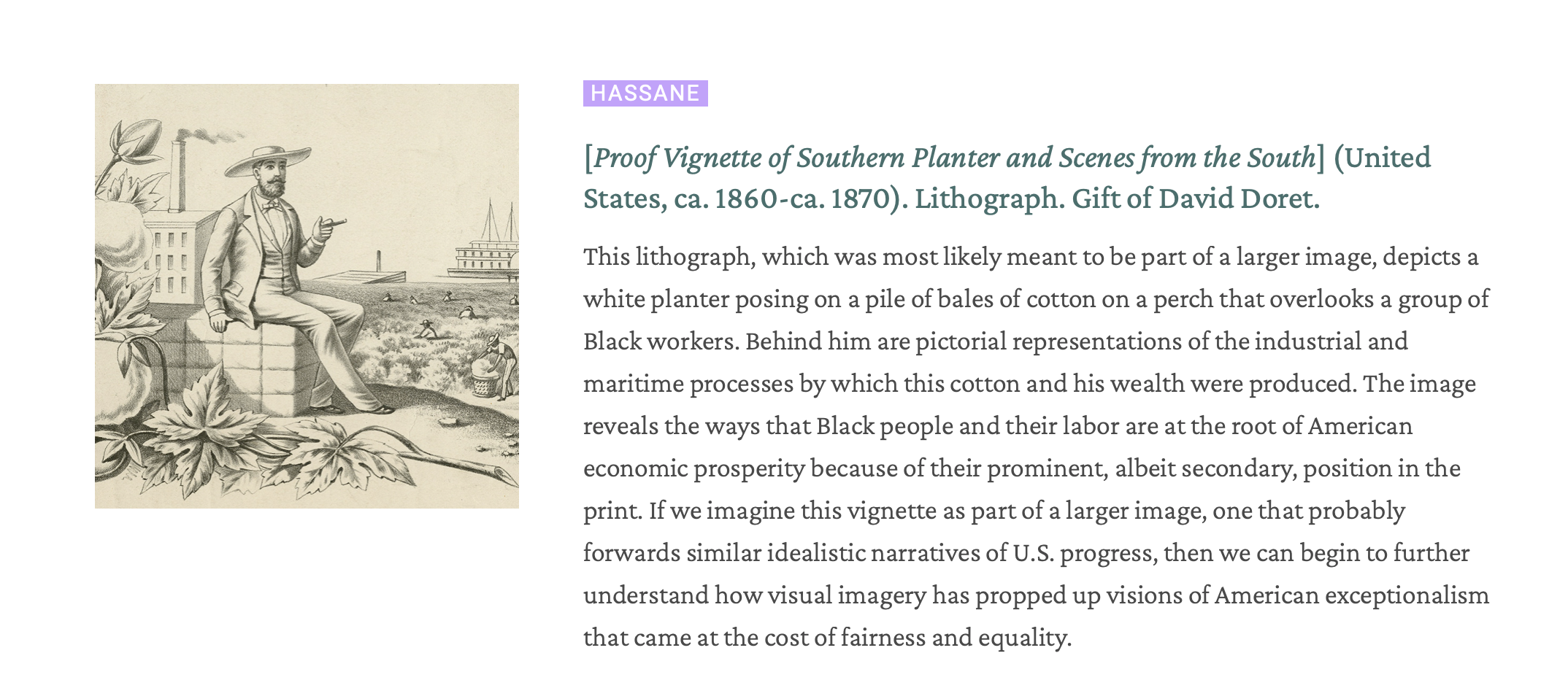

Curatorial perspective is addressed directly in the digital exhibition’s final section, “Made You Look: Three Curators’ Perspectives on the Graphic Arts,” developed by Hassane. This section both deconstructs and redistributes curatorial agency. Long gone is the singular voice of authority that characterized much label writing and cataloging in the past. Each curator wrote an object label for four historical visual artifacts that have complex stories in relation to race and gender. The purpose, as Hassane articulates, is “to illuminate the fruitfulness of considering multiple viewpoints, whether they are disparate or overlapping,” so that “seeing our different perspectives can allow you to consider yours.”9 This kind of antiracist approach, intended to reveal “(un)conscious bias and multiple viewpoints,” is extended in the digital catalogue. The curators invited four guest cataloguers to write entries for a daguerreotype, lithograph, and watercolor, all from the nineteenth century. A diverse group, the guest cataloguers include two graphic arts curators, a scholar of American art history, and a contemporary artist and designer.10 The digital catalogue offers multiple pathways for readers to test their own perceptions against these entries. Readers can view the visual materials without interpretation, choose to read all cataloguers’ entries for an object, or elect to read the entries written by one cataloguer. The multiperspectival catalogue and label writing in Imperfect History is both fine-grained and an intriguing demonstration of the impact that personal predispositions can have, suggesting the cumulative impact of the biases that shape the fields of American art history, visual culture, and photography. Especially for those teaching museum studies or art history, such an exercise helps increase students’ awareness of how curators’ perspectives, as well as their own, impact their work as knowledge and content producers; it is a vivid reminder that “museums are not neutral.”11

Despite the importance of sharing multiple authors’ perspectives, in the “Made You Look” section, a different design could have provided greater clarity. The shifting curators can be difficult to distinguish visually, since only colored rectangles around the curators’ surnames signal a label’s author (fig. 2). Moreover, because labels are presented sequentially and have to be read by scrolling down the page, it is difficult to compare them, which is the intention of the section. Since an image is tied to the first entry, it is also impossible to consider the graphic material being discussed while reading each of the entries. The conceptual links between this section of the digital exhibition and the digital catalogue are apparent after reading both. But as these projects are presented, there is no access directly between them. In order to read the digital catalogue, viewers have to go to a separate landing page that links all components of Imperfect History. The digital organization thus frustratingly cordons off the digital catalogue from the digital exhibition as well as from the other content.

Thinking across Imperfect History’s many components, there are further opportunities to build connections between the exhibition and the plethora of video content, blog posts, and social-media posts, which are neither linked nor referenced in the digital exhibition, leaving readers to make their own intellectual and visual linkages. While the landing page highlights the multiple aspects of the project, it does a disservice to the digital exhibition. From the main Imperfect History page, it is confusing to find and access the digital exhibition; it requires clicking on “Exhibition” and then scrolling down to a menu at the bottom of the page and clicking on a link for “Digital Exhibition.” This unclear navigation belies the digital exhibition’s importance.

Overall, the power of the Imperfect History digital exhibition is in its curatorial transparency and the institutional accountability that it promotes. That extends to collection development and changing modes of preservation. The sections “Inception, Collection, Reception: Reading the Graphic Arts Collection” and “As Time Goes By: Snapshots of the Evolution of the Graphic Arts Collection, 1731–2021” lead viewers through shifting collecting priorities and the major donations and acquisitions that altered the collection. These sections illuminate how all collections have gaps and indicate how acquisitions and donations can reinforce those lacunae or help to address them. It is fascinating to learn how now–well-known visual artifacts entered the collection and were initially curated or ignored. For instance, early library stewards placed many of Edward Clay’s racist images of African Americans in a “scrapbook of caricatures” when they entered the collection in the 1890s. The scrapbook was a technique deployed for many visual artifacts in this period, forcing new associations and obscuring inscriptions in an effort to unite “like” materials for ease of access and storage. The digital exhibition missed the opportunity to give viewers virtual access to one of these scrapbooks; the ability to page through a digital facsimile would have strengthened viewers’ connection with this complex format and helped to infuse a sense of materiality and scalar specificity. As it is, the digital exhibition presents almost all objects, regardless of their actual measurements, in same-sized virtual images. This presents a uniform appearance but creates a false equivalency between small and large graphic materials. Adding to this scalar blurring is the fact that no dimensions are included as part of the labels. While the viewer can zoom in and out, it is difficult to get a sense of the works as graspable physical objects.12

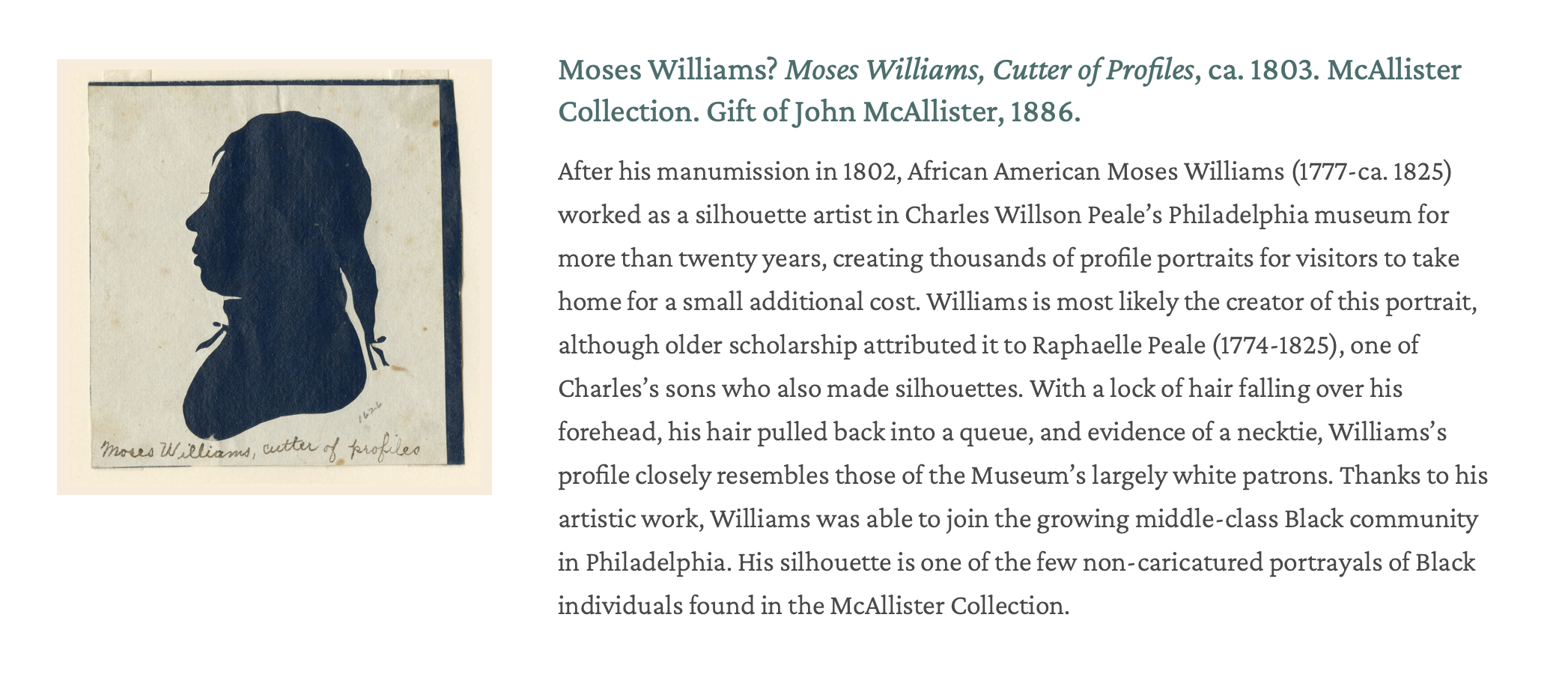

In addition to the Clay caricatures, the digital exhibition reveals how a famous collection object, Moses Williams’s powerful c. 1803 silhouette self-portrait, entered the collection by a circuitous route. It came as part of an 1869 major gift from Dr. James Rush, who bequeathed the massive collection of his father (Dr. Benjamin Rush), which encompassed hundreds of silhouettes from Peale’s Museum. Here, too, a glimpse beyond Williams’s silhouette, which is presented in isolation (fig. 3), could have allowed viewers to experience the object in this initial archival context. As it is, the only hint of earlier formats remains in the pieces of visible adhesive that bind the silhouette to a paper support. Despite the fact that the silhouettes entered the collection in the nineteenth century, curators did not accession the works until 1991, perhaps an indicator of the lesser value ascribed to the medium historically. Thanks to the scholarship of Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, these images are now recognized as primarily the work of the enslaved artist Moses Williams.13 Through Williams’s silhouette self-portrait, the exhibition illuminates how an institution’s decisions about not only what to acquire but what to catalogue impacts which histories researchers are able to support using archives. Equally important is how this section enables viewers to see the impact of significant donations. Notable is the album of Richard DeReef Venning (c. 1865–c. 1922), a record of African American family, community, and middle-class spaces in Philadelphia donated by the Stevens-Cogdell/ Sanders-Venning family in 2012. This donation strengthened and encouraged the Library Company’s now-significant holdings of visual materials that depict or were created by African Americans.

Imperfect History centers the curatorial perspective. As the donation by the Stevens-Cogdell/ Sanders-Venning family suggests, however, community members are a vital part of the institution’s past and future. The incorporation of more interactive supplementary content in the forms of blog posts, audio clips, or videos could have helped to include voices beyond those of the curators and to spur viewer engagement in what appears to be a static and “finished” digital exhibition. The addition of something like the series of interviews included in the site for the Yale Center for British Art’s exhibition Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain could have brought the multiplicity of perspectives included in the digital catalogue to the digital exhibition in the form of responses to specific visual artifacts.14 Reactions from donors, other staff, or Philadelphia community members could have furthered the exhibition’s possibilities for antiracism and included perspectives beyond that of the curator, which both shapes and limits its focus. Perhaps the Library Company’s role as a research institution discouraged curators from explicitly addressing the community involvement that has been a primary motivator for change at many institutions.15

Despite these limitations, Imperfect History will prove useful for those teaching about, and working as, museum professionals at other institutions, as well as for all those asking how best to pursue antiracist and anticolonial practices in relation to the legacies of white-centered, patriarchal, and heteronormative collections.16 Given its 1731 founding, the Library Company has an exceptionally long institutional history, but the issues addressed here are nevertheless representative of most collections of graphic arts. While the digital catalogue and exhibition format provide a model for the ethical interrogation of a collection and the difficult artifacts within it, the feasibility of achieving this at smaller sites without the benefit of grants by the Henry Luce Foundation is unlikely. Nor does the museum field need hundreds of variations on the microhistory so deftly and thoroughly presented here. Imperfect History, then, does not directly point the way forward for other institutions seeking a modular digital solution. Rather it documents one successful approach in a larger and ongoing collective reassessment. I look forward to seeing the multiple ways that institutions document their own “imperfect” histories as they use digital tools to direct a critical gaze both inward and outward in order to forge more inclusive paths forward.

Cite this article: Jennifer Van Horn, “Telling Imperfect Histories with the Digital,” review of Imperfect History: Curating the Graphic Arts Collection at Benjamin Franklin’s Public Library, online exhibition at The Library Company, Philadelphia, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.14595.

Notes

- Library Company of Philadelphia, Imperfect History: Digital Catalog, 2021, https://ihcatalog.librarycompany.org. ↵

- Imperfect History: Curating the Graphic Arts Collection at Benjamin Franklin’s Public Library (digital exhibition), https://librarycompany.org/digital-imperfect-history. ↵

- It is important to note that activists and protestors within and beyond the museum field have long called for, and continue to advocate for, changes to make museums more inclusive. Protesters called for action during the summers of 2020 and 2021 and still do so. See, especially, LaTanya Autry and Mike Murawski, Museums Are Not Neutral, accessed May 20, 2022, https://www.museumsarenotneutral.com; Museum Hue, accessed July 15, 2022, https://www.museumhue.com/about-hue; @ChangetheMuseum (Instagram), accessed May 20, 2022, https://www.instagram.com/changethemuseum; Wendy Ng, Marcus Ware, and Alyssa Greenberg, “Activating Diversity and Inclusion: A Blueprint for Museum Educators as Allies and Change Makers,” Journal of Museum Education 42, no. 2 (2017): 142–54; An Empathetic Museum is an Antiracist Museum (blog), October 12, 2020, http://empatheticmuseum.weebly.com/blog–honor-roll/an-empathetic-museum-is-an-antiracist-museum; and StrikeMoMA, accessed May 20, 2022, https://www.strikemoma.org. ↵

- The physical exhibition was open September 2021–April 2022 at the Library Company. The workshop was held in the summer of 2021. See Library Company of Philadelphia, 2021, https://librarycompany.org/imperfect-history/exhibition and https://librarycompany.org/imperfect-history/vis-lit-workshop. The digital content is consolidated on one landing page: https://librarycompany.org/imperfect-history. ↵

- Library Company of Philadelphia, Imperfect History, 2021, https://librarycompany.org/digital-imperfect-history/section3.html. ↵

- Erika Piola, “Wanting to Kick Myself: My First Days in the Graphic Arts Department” (blog post), Library Company of Philadelphia, Imperfect History, 2021, https://librarycompany.org/2020/06/16/wanting-to-kick-myself. ↵

- The exhibition “makes visible the often unseen people, places, meanings, and aesthetics—’the hidden lives’—of the pictorial records representing the Library Company’s distinct and multifaceted history.” Library Company of Philadelphia, Imperfect History, 2021, https://librarycompany.org/imperfect-history/exhibition. ↵

- The curators’ (and guest Shawn Michelle Smith’s) comments succinctly laid out their approach to this term. See Library Company of Philadelphia, “Exhibition Opening: Imperfect History and the Archive, with special guest Shawn Michelle Smith,” January 20, 2022, video, 1:33:28, https://youtu.be/4_LLBuG7Cig. ↵

- Library Company of Philadelphia, “Made You Look: Three Curators’ Perspectives on the Graphic Arts,” Imperfect History, 2021, https://librarycompany.org/digital-imperfect-history/section6.html. ↵

- The guest cataloguers were Lauren B. Hewes, Clayton Lewis, Tanya Sheehan, and Joy O. Ude. For their biographies, see Library Company of Philadelphia, Imperfect History, 2021, https://librarycompany.org/imperfect-history/digital-catalog. ↵

- Autry and Murawski, Museums Are Not Neutral; see also La Tanya Autry and Mike Murawski, “Museums Are Not Neutral: We Are Stronger Together,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://journalpanorama.org/article/public-scholarship/museums-are-not-neutral. ↵

- For scalar specificity, see Jennifer Roberts, “Introduction: Seeing Scale,” in Scale: Terra Foundation Essays, ed. Jennifer Roberts (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 2:10–24. ↵

- See, especially, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, “A Cutter of Profiles,” Lapham’s Quarterly, June 26, 2018, https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/cutter-profiles. ↵

- Yale Center for British Art, “Slavery and Portraiture in 18th-Century Atlantic Britain,” “Listen” tab, https://interactive.britishart.yale.edu/slavery-and-portraiture/audio. ↵

- I recognize the multiplicity and sometimes conflicting meanings of the word “community” for museum professionals. For an entry into thinking about “community,” see Ruth B. Phillips, introduction to Museums and Source Communities, edited by Laura Peers and Alison K. Brown (New York: Routledge, 2003), 155–70. ↵

- I acknowledge the complexity of the terms “anti-colonial” and “decolonize” in relation to museum work and the importance of Indigenous efforts to decolonize land ownership. See Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40. I am inspired by the definitions for “decolonize” put forth in Huey Copeland, Hal Foster, Davi Joselit, and Pamela M. Lee, “A Questionnaire on Decolonization,” October 174 (Fall 2020): 3–125. For an analysis of the possibilities and potential co-option of “decolonizing,” see Sumaya Kassim, “The Museum Will Not Be Decolonised,” Media Diversified, November 15, 2017, https://mediadiversified.org/2017/11/15/the-museum-will-not-be-decolonised. ↵

About the Author(s): Jennifer Van Horn is Associate Professor of Art History and History at the University of Delaware.