Joseph E. Yoakum: What I Saw

Curated by: Mark Pascale, Esther Adler, and Édouard Kopp

Exhibition schedule: Art Institute of Chicago, June 12–October 18, 2021; Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 28, 2021–March 19, 2022; Menil Collection, Houston, April 22–August 7, 2022

Exhibition catalogue: Mark Pascale, Esther Adler, and Édouard Kopp, eds., Joseph E. Yoakum: What I Saw, with contributions by Esther Adler, Katheen Ash-Milby, Mary Broadway, Clara Granzotto, Whitney Halsted, Édouard Kopp, Faheem Majeed, Laura K. Minton, Emily Olek, Mark Pascale, and Ken Sutherland, exh. cat., Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2021. 252 pp.; 200 color illus. Cloth: $50.00 (ISBN: 9780300257489)

Who was Joseph Yoakum? The exhibition Joseph E. Yoakum: What I Saw, organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and also traveling to the Menil Collection and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) (where I saw it), foregrounds this question through the artist’s social circle, his approach to drawing, and his extensive travels. His oft-recited biography goes something like this: in 1962, at the age of seventy-one, Yoakum had a dream that inspired him to draw (16, 30). Five years later, his landscape drawings—prominently displayed in the window of his storefront studio—caught the eye of Chicago State University anthropology professor John Hobgood. Yoakum’s quick rise to popularity afterward recycles the discovery tropes woven through biographies of many Black “self-taught” artists. He was befriended by the (largely white) artist community of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), who collected and promoted his highly detailed drawings of both real and imagined topographies. What I Saw complicates this narrative by bringing together more than one hundred of Yoakum’s images from myriad collections across the United States. It offers a fuller picture of the artist’s life and work, incorporating Yoakum’s rarely exhibited sketchbooks and figurative drawings alongside an analysis of his technical evolution.

What I Saw considers movement and travel as a curatorial methodology, drawing on Yoakum’s own experiences working for various circuses and his later deployment overseas during World War I. While this approach has been previously employed in shows such as Traveling the Rainbow: The Life and Art of Joseph E. Yoakum (Museum of American Folk Art, 2001), What I Saw distances itself from murky biographical details and the artist’s relationship with the Chicago Imagists.1 Yoakum’s biography is marked with ambiguities and contradictions, and many of his drawings are undated. In response, What I Saw does not attempt to organize his works chronologically—instead, MoMA’s curatorial team constructs groupings based on thematic and formal elements. These include Yoakum’s approaches to drawing and materials, landscapes, and figurative works.

The didactic texts examine Yoakum’s interpretation of the natural world, his mark-making processes, and his self-articulated identity. Each new section offers additional information about the artist without limiting the work to a strictly biographical interpretation. While this gesture may be a common interpretive strategy in contemporary exhibition practice, most “self-taught” or “outsider” artists, especially those of color, have historically not been given such treatment. What I Saw attempts to intervene in decades of racist, classist, and generally uncritical scholarship on the work of artists associated with such nomenclatures. Rather than make a claim about Yoakum’s identity or even the validity of his stories, it presents him as a complex—and complicated—figure of twentieth-century American art.

The exhibition begins with a black-and-white photograph of the artist in his studio. In this introductory room, viewers are encouraged to spend time in Yoakum’s workspace: we are provided with an intimate portrait of his studio setup and chosen materials, lit by a lone light source over his drawing table. A label indicates that the image was taken by Roger Vail (b. 1945), who was, at the time, an art student at SAIC. Yoakum appears relaxed, with a half smile, poised with hands on his knees as if ready to rise and show us around. This is one of many images taken by Vail of Yoakum’s Eighty-Second Street home studio in Chicago—others not selected for the exhibition portray him looking more apprehensive about being photographed.2 Here, the exhibition’s design team chose their accent wall colors carefully, as the subtle variations of deep blue anticipate Yoakum’s own palette that unfolds throughout the galleries.

In the succeeding small room, a short didactic text introduces Yoakum alongside three drawings that are autobiographical in subject. Back Where I Were Born 2/20-1888 AD (1965), What I Saw in Alberta B.C. Pacific Coastal Range (n.d.), and Mt Annaconda in Annaconda Mtn Range near by Annaconda Montana (stamped 1968) are rare examples of the artist referencing his experiences in the first person. As a curatorial gesture, hanging Yoakum’s few autobiographical works together—and at the exhibition’s entry—is reparative. Apart from his sketchbooks and a few letters, the majority of Yoakum’s life story has been told through the archives of artist Christina Ramberg and art historian Whitney Halsted. Other narratives were drawn from letters he wrote to Gladys Nilsson and Jim Nutt, who befriended, collected, and sometimes promoted his work. As the exhibition’s catalogue cautions, telling (and retelling) Yoakum’s story through a circle of white historians, artists, and critics presents an imbalanced narrative (16).

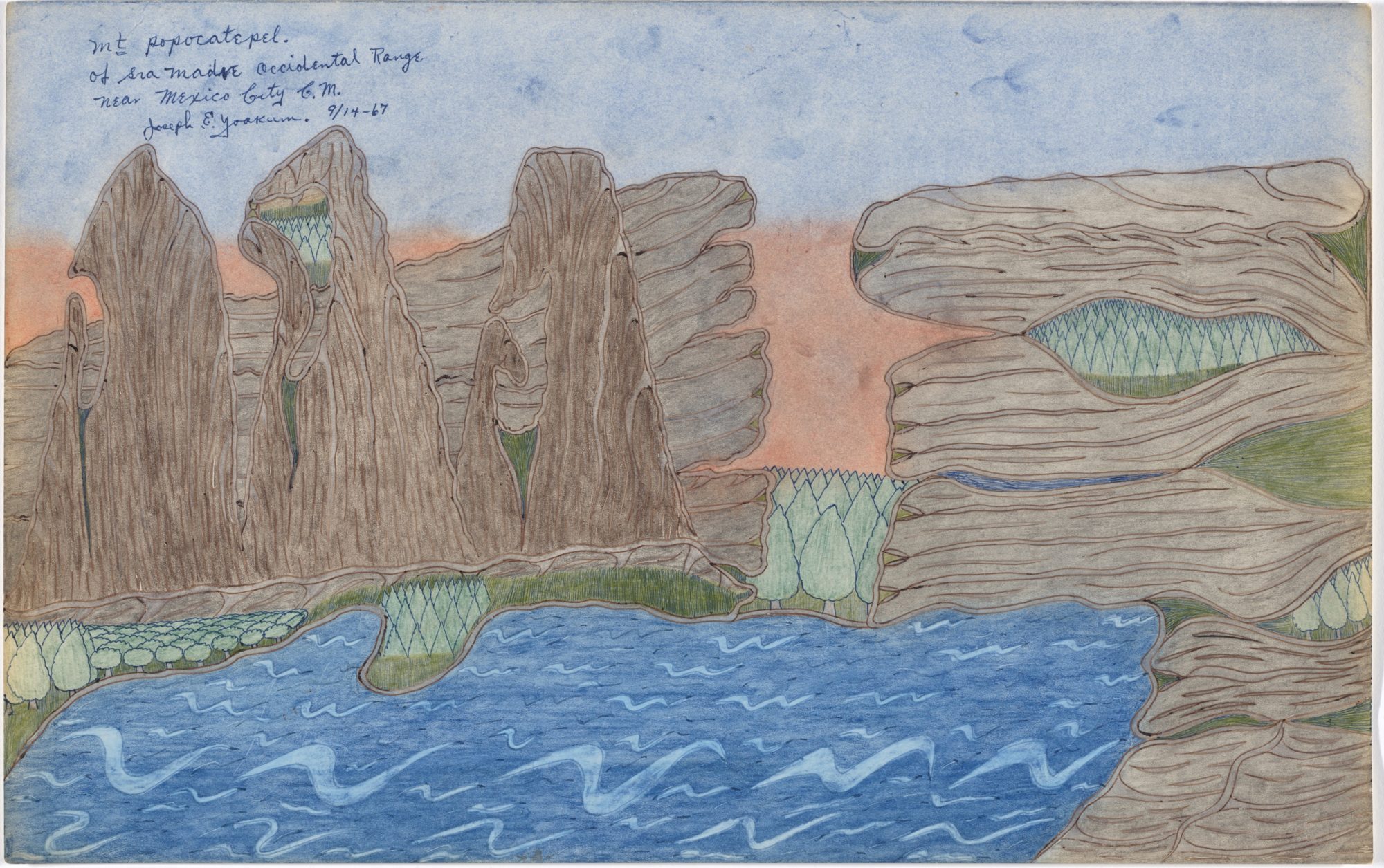

The striking visual impact of Yoakum’s work is most evident upon entering the main room of the Tatyana Grossman Gallery—MoMA’s dedicated space for the display of prints and drawings (fig. 1). When viewed as a collective entity, Yoakum’s drawings are better understood as a form of storytelling. On closer inspection, most landscapes indicate their location in small lettering on the bottom or top margins, sometimes accompanied by a signature or date. They deviate from traditional landscape imagery, which employs linear perspective to indicate depth, utilizing instead intricate linework to convey variations of geological and topographic elements. Yoakum’s application of dark, sinuous lines and saturated color—mostly blues, purples, greens, and yellows—give the illusion of movement when seen from a distance. He used toilet paper to effectively blur the edges of large swaths of color, resulting in an atmospheric effect. Mt Popocatepel of Sra Madre Occidental Range near Mexico City C.M. (1967) (fig. 2) exemplifies this smudging process. In this landscape that appears bisected by a series of geological formations, Yoakum has carefully blended blue and red together to produce a striking sunset or sunrise.

Yoakum’s graphic technique is a central theme of What I Saw. In the main gallery space, his early ballpoint-pen drawings—produced without color—are paired with explanatory labels. In this section, Caucasus Mtn Range USSR—Russia (1965, stamped 1964) and The Great Mtn Range Near Canberra Australia (stamped 1964) are displayed together, illustrating Yoakum’s use of linework to indicate deep mountain crevasses. A label nearby explains that Yoakum would frequently create copies of his drawings to experiment with color and dramatic shading. Some works, such as Bitter Root Range Near Boise Idaho (1962), are marked with the text “Model Don’t Paint” to remind the artist not to add color, therefore leaving only the outlines visible. The term “visionary” has often been used to describe Yoakum’s unconventional drawings—and indeed, he was prompted to begin making art after having a pivotal dream. What I Saw is clearly invested in showcasing Yoakum’s processes and takes seriously his drafting skills, further complicating the term “visionary,” since it has often been used to minimize the skill sets of artists without formal training.

The Grossman Gallery is free-flowing, allowing thematic groupings to inform one another. Near the exit of What I Saw are Yoakum’s figure drawings that were traced from the pages of popular magazines. Idealized portraits of white women and Native Americans are accompanied by a text panel titled “Yoakum’s Shifting Self-Identity.” Viewers are confronted with a complex portrait of Yoakum as someone who identified as being of African, European, and possibly Native American heritage and who performed a fictionalized version of Navajo identity. He rejected the label African American—a decision that contributing catalogue essayist Kathleen Ash-Milby thoughtfully considers in her essay, “Back Where I Were Born: Joseph E. Yoakum and the Imaginary Indian.” She writes: “The Native American narrative allowed him to be exceptional, to embrace romantic cliches, and most importantly, to push back against a society that expected him to be inferior” (72).

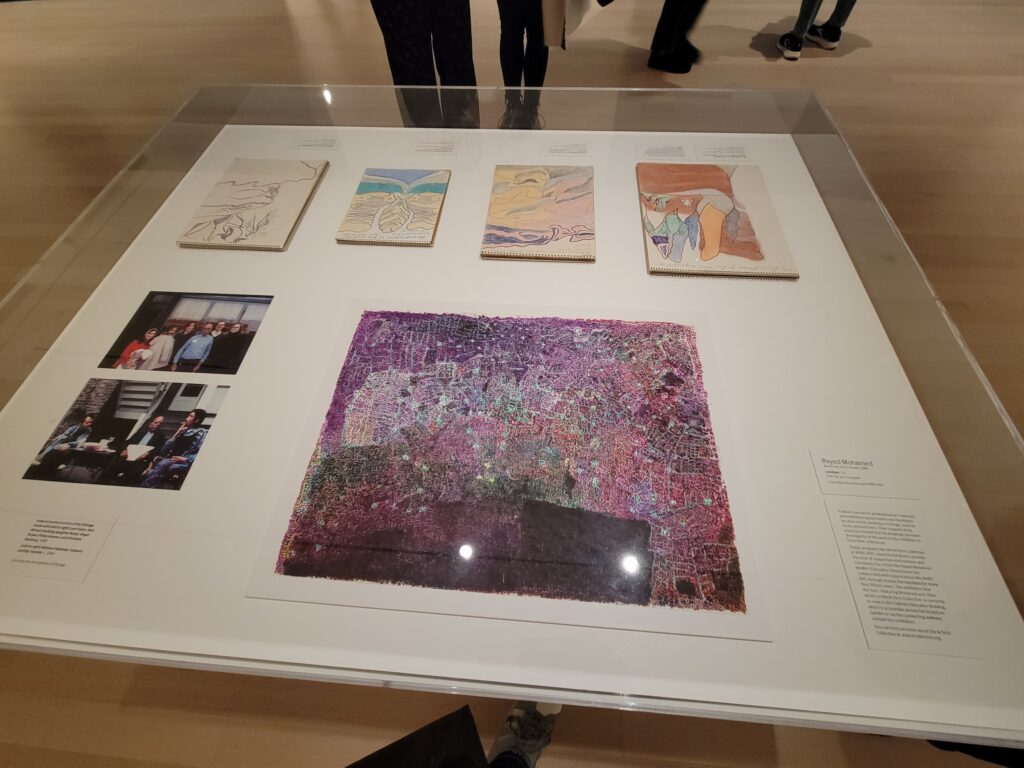

In the room’s center, a small table case displays four of his sketchbooks, two photographs of the artist with his Chicago Imagist network, and a work by the living American artist Rayed Mohamed (fig. 3). Here is where the exhibition’s careful presentation begins to unravel: the corresponding label explains that Yoakum, like Mohamed, was supported and championed by his peers. Mohamed was also included in a concurrent MoMA exhibition titled How Are You?, which features artists in the ArTech Collective—an organization that supports neurodivergent artists in developing their practices. This connection haphazardly links both artists as “outsiders” without employing the word outright. It negates their individual approaches and decisions for drawing, which have very little in common outside of their intricate linework.

The Museum of Modern Art has a long—and contentious—history of engaging with artists of color that they considered “self-taught” or “visionary.” Bridget R. Cooks’s book Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum (2011) draws attention to the failings of white institutional frameworks, which have often limited our understanding of such artists.3 She examines MoMA’s first exhibition of a Black self-taught artist, William Edmonson, in tandem with the museum’s interwar cultural agendas. In this case, Edmonson was portrayed as “primitive,” as someone who produced work without an understanding of the larger art-historical narrative. What I Saw does not recycle this egregious framework, and its curatorial team has empathetically presented expansive documentation of Yoakum’s life and work. Yet, in its attempt to include Yoakum within the canon of American drawing, MoMA never addresses why he was excluded in the first place. MoMA and other similar large institutions have made recent strides to incorporate so-called folk, self-taught, or outlier artists within their holdings without grappling with the nomenclatures themselves—a reminder that mere inclusion fails to do the hard, ongoing, reparative work that is necessary.

Cite this article: Elizabeth Driscoll Smith, review of Joseph E. Yoakum: What I Saw, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.13354.

PDF: Smith, review of Joseph E. Yoakum

Notes

- The Chicago Imagists were not a formal group but rather a network of artists who exhibited at the Hyde Park Art Center in the late 1960s under Don Baum’s leadership. They included Roger Brown, Barbara Rossi, and Ray Yoshida, among many others, who were interested in “the vernacular, the comedic, and the grotesque” (17–18). ↵

- For an example, see Vail’s photograph included in Emily Olek, “Crossing Paths: The Friendship and Partnership of Joseph Yoakum and Whitney Halstead,” Art Institute of Chicago, July 27, 2001, https://www.artic.edu/articles/918/crossing-paths-the-friendship-and-partnership-of-joseph-yoakum-and-whitney-halstead. ↵

- See Bridget R. Cooks, Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011). ↵

About the Author(s): Elizabeth Driscoll Smith is a PhD Candidate at the University of California, Santa Barbara.