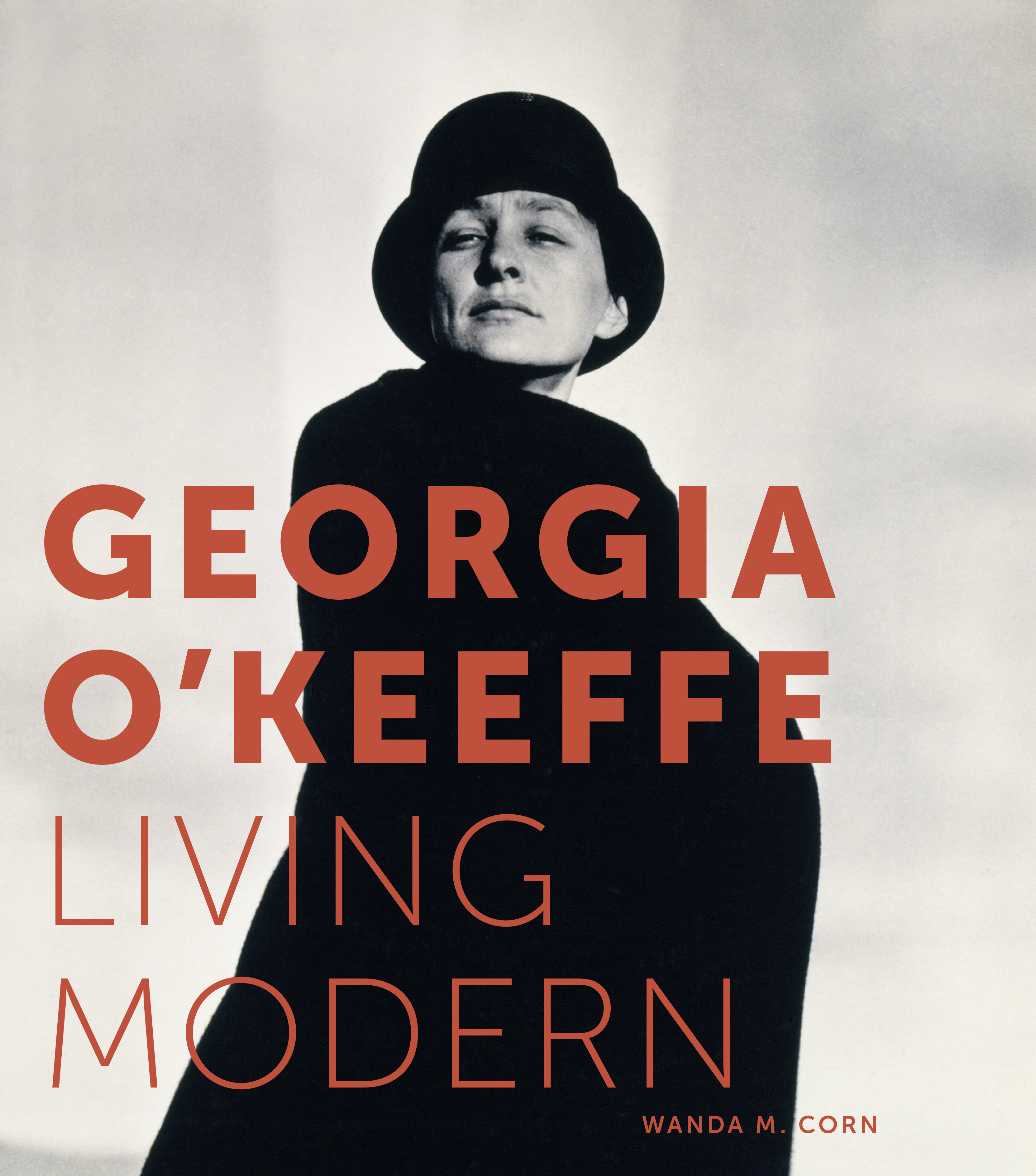

Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern

Wanda M. Corn

Wanda M. Corn

Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum in association with DelMonico Books/Prestel, 2017. 320 pp.; 217 color illus.; 112 b/w illus. Hardcover, linen $60.00 (ISBN: 9783791356013)

Wanda Corn intends her latest project, Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern, to be a contribution both to the study of one of the most well-known American artists of the last century, and to the field in general. She wants us to consider Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), and by implication other modernist artists, within an arena larger than their art and its reception: their art and their lives together, a Gesamtkunstwerk, as she calls it. She hopes to open “doors through which future students of art and art history will pass (283).” And she succeeds. Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern is a sumptuously produced and exhaustively documented monograph. “This book . . . testifies to what an art historian can glean from the material culture an artist leaves behind (12),” she writes. Indeed it does.

Corn had previously examined Gertrude Stein’s life as a piece of performance art, in part through looking at her clothes as costumes.1 Following this, Corn notes that Barbara Buhler Lynes, the dean of O’Keeffe studies, mentioned to her that O’Keeffe’s clothes closets presented a full range of O’Keeffe’s life in dress and were available for study. This book and the related exhibition are the result.

Corn maps the clothes against O’Keeffe’s life along two axes: as an oeuvre comparable to her oeuvre of paintings, and as an element in the many devices O’Keeffe used to create an image or a performance of herself as an artist. The book is primarily organized along very much the same lines as any monographic study of O’Keeffe’s paintings. The first chapter is devoted to her slow beginnings as a student studying to become an art teacher, to a short passage working in fashion illustration, to her last teaching job in Texas. The second chapter is devoted to the New York years with Alfred Stieglitz in the 1920s and early 1930s; the third to her reinvention of herself in New Mexico from the mid-1930s onward. The last chapter is devoted to O’Keeffe’s last work, from the 1950s, with a final epilogue considering her influence. Where Corn radically diverges from the usual monograph on O’Keeffe is the fourth chapter, devoted to O’Keeffe’s Asian influences, which in a monographic account of O’Keeffe’s paintings gets short shrift because there is no coherent body of work associated with her fascination with Asian art. As any scholar does when approaching O’Keeffe, Corn marvels at her “amazing continuity”—the fact that O’Keeffe, once she decided on something that was right for her, rarely changed her mind or deviated from the decision. This is as true of the spirit of her clothes as it is for the vocabulary of abstraction that undergirds her art-making from her first independent drawings in 1915 to the very end of her career in the 1970s.2

Corn’s approach has both the strengths and limitations of a monographic approach. The strength arises from the deep and rich picture we gain of O’Keeffe. Where Corn pays scant attention is the context of O’Keeffe’s decisions, offering only cursory explanations. O’Keeffe was one of the very last major figures from the very first generation of abstract artists who was still painting abstractions; there certainly is amazing continuity from first to last in the abstract visual language out of which her paintings are generated. But it is harder to say that so easily about her costume performance. As a “New Woman” of the 1910s and 1920s, Corn situates O’Keeffe between the feminist theorist and writer of a slightly earlier generation, Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935), and Coco Chanel (1883–1971), just four years older than O’Keeffe, whose first casual wear collections were featured in the America press by 1916. But Chanel bobbed her hair, while O’Keeffe never adopted this fundamental sign of modernity; she wore her hair long all her life. The bob, made fashionable by the dancer Irene Castle by 1915, had become one of the essential signs of a young woman’s modern identity, along with slim, short dresses, by the 1920s. This is the costume and look of the flapper, a term and an idea one could never associate with O’Keeffe. It is important to remember that by the time O’Keeffe met Stieglitz and moved to New York she was thirty. She was young during the Progressive Era, before World War I, and the amazing continuity of her style (whether clothing or painting) dates from then. At the same time, as Corn makes clear, the radical rupture in O’Keeffe’s costuming of herself comes when she relocates to New Mexico, the same moment when one would identify a decisive shift in her paintings. But perhaps the shift in costume and image is greater than the one in her paintings, where the change in subject matter masks the fundamental continuity in the way O’Keeffe constructs her paintings. It is wonderfully liberating to think of O’Keeffe herself as a Gesamtkunstwerk, but one where the various elements are not necessarily working together in sync, and where the differences throw O’Keeffe’s psychology into high relief.

Chanel, as she evolved as a designer, continually changed her clothes to keep herself young and relevant, while retaining the same basic aesthetic (her audience did not age along with her, one of the big differences between producing fashion and painting). It is astonishing in contrast to see how quickly O’Keeffe ceases to be young and becomes timeless: by the early 1930s she is dressing in long black robes that look like nuns’ habits. Her dress is essentially sexless. Or perhaps it is better to say she is mature. It is an exceedingly useful corrective to our usual image of O’Keeffe as a strong feminist modernist (flavored in our minds retroactively by her Western image), to see the long, severe and pleated black wool outfit with two white and two black long ribbons hanging down from the neck (81). She wears a version of the dress in a set of photographs of her and Stieglitz taken at his gallery An American Place by photographer Cecil Beaton in 1946 (80). Stieglitz is wearing his usual black cape, and he and O’Keeffe together look both compatible and uncompromisingly severe. One realizes that O’Keeffe has positioned herself outside fashion, or perhaps just adjacent to it, but not in the swim of it. This is made abundantly clear in several of the photographs when an unidentified woman in contemporary dress appears in the background. O’Keeffe’s costume looks like a reproof. In the exhibition (as seen in Cleveland) this dress overwhelmed the art exhibited near it.

At the core of her costume performance is the working through of the experience of being photographed by Stieglitz, and her reinvention of her image in New Mexico. That Stieglitz’s photographs of O’Keeffe nude, which he exhibited in the 1920s, both made O’Keeffe a celebrity and trapped her within a sexualized reading of her art is well-known, and discussed by Corn at some length. Corn distinguishes five elements in the typology of the First Photographer’s Woman Portrait (Corn’s ironic formulation of Stieglitz’s heavy hand): Sexual Woman, Artist Woman, Nature Woman, Modern Woman, and Spiritual Woman (95–101). Corn argues that it is the last, O’Keeffe as “artist-nun” that becomes the bedrock of the self-fashioned image that O’Keeffe developed in New Mexico and remained even as “younger generations knew her only as a Westerner, and not as the famous wife of a famous husband with a New York address (104).” Speaking of O’Keeffe’s New York address, Corn provides an excellent analysis of O’Keeffe’s residences in Texas and New York in “Domestic Self-Fashioning: O’Keeffe’s Early Residences” (106–11) which, along with Erin Coe’s Modern Nature: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George, gives all the information one needs about where O’Keeffe lived until she got to New Mexico.3 Corn’s chapter is one of a series of illuminating sidebar sections that populate the book. For example, “Contracts and Commissions” (112–15) provides an excellent summary of O’Keeffe’s work with Cheney Silks and Elizabeth Arden.

The chapter on O’Keeffe in New Mexico adds considerable nuance, however, to the simple view of the artist as a Westerner. “Artful Homes and Studios” (184–91) considers O’Keeffe’s houses as part of her performance (with wonderful photographs of her kitchen at Abiquiu). Photographs of O’Keeffe’s jewelry show that she succumbed to Southwest Native American silverwork like everybody else (but only in the most minimalist way); adding a discussion of her acquisition of Marimekko fashions complicates the image of her in jeans and a bandanna. But just as Corn positions O’Keeffe between Gilman Perkins and Chanel in the first chapter, it might have been interesting to have enlarged the focus so that we could see what Mabel Dodge Luhan was doing, or when women in jeans first show up in popular media (were there cowgirls in Hollywood in the 1940s other than Dale Evans?). Corn works through the various photographers that O’Keeffe permitted to photograph her in the section “In Front of the Camera” (169–83) in the most comprehensive overview of how O’Keeffe managed her image. This focus on image is the natural set-up for the last chapter, on O’Keeffe’s celebrity, with an amusing final section on “Artist Homages.” With an epilogue on O’Keeffe’s lasting influence on the world of fashion, the book comes full circle, from O’Keeffe adapting the fashions of figures such as Chanel to influencing them. The amazing continuity that Corn argues for is most visibly seen in the section on “The Black Suit” (242–50), where a black suit by Eisa (Cristóbal Balenciaga, Spanish) forcibly reminds the viewer of the black dress mentioned previously, designed and made mostly by O’Keeffe herself. The line is a little cleaner; there are fewer pleats; the ribbons and hem are shorter—but that is about it.

The most unusual chapter is the one on Asia, chapter four, which fits no monographic model. Asian art had been an element of O’Keeffe’s interests at least since her studies with Arthur Wesley Dow in the 1910s. She owned many books on Asian art and paid great attention to the Asian galleries of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Finally, in 1959, she visited Asia. She ordered clothes from tailors in Hong Kong, bought kimonos, and so on. Corn comments: “Few items of traditional Japanese and Chinese clothing seem to have gotten past O’Keeffe.” This deep involvement with Asian clothing justifies Corn’s claim that attention to O’Keeffe’s non-painting life illuminates her art. Just about the only aspect of her painting career not mapped against her clothes is her Hawaiian episode of 1938, which produced over twenty paintings but, sadly, no Hawaiian shirts.

The most interesting aspect of Corn’s work is perhaps her methodology. In an odd way, the book, which aims to overturn our narrow conception of what an artist is really doing in her work, succeeds on two very old-fashioned foundations: biography and connoisseurship. For O’Keeffe studies, biography has been inescapable, as it is for the study of any artist who has become popularly famous. (Indeed, I can think of no study of an artist who is either famous, or is being returned to visibility, that does not rely on biography.) But the connoisseurship aspect of Corn’s project is remarkable and rather lovely to behold, for several reasons. First, it brings into American art an interdisciplinary methodology that has been successfully revived in other fields, notably early Netherlandish painting. In that field, and increasingly throughout object-based art history, teams of conservation scientists and scholars are pooling knowledge and disciplines to examine the objects on which the field has grown through new technologies, often with remarkable results. It is heartening to see Susan Ward, a fashion scholar, work with Corn to describe, date, and attribute O’Keeffe’s clothes. In one charming aside, Corn comments that the group is all of a generation to remember the Marimekko slip dresses that O’Keeffe wore in the 1960s (297). It is also a little amusing to resurrect the notion of the artist’s “hand” out of the “early” material: Corn and her colleagues, Ward and curator Carolyn Kastner, convincingly attribute one set of costumes to O’Keeffe’s own seamstress skills. Corn, through this attribution, is then able to compare the mental habits required for this kind of fine work to O’Keeffe’s similarly focused and obsessional paintings, and indeed her whole attitude to her public persona. All is of a piece.

One could go further; Corn tends to limit comparisons to O’Keeffe’s paintings to color, but her very painting technique bears comparison to her sewing. There are few records of O’Keeffe at work, but in at least one instance a journalist describes her as beginning in the top left corner of the painting and working her way methodically down the canvas. Her painting technique is similarly scrupulous and organized, the surfaces of her paintings barely registering the carefully calculated brushstrokes that bring the color and form to the blank surface. Painting, for O’Keeffe, is a structured, sequential project of one considered step after another, such as sewing. Corn discusses O’Keeffe’s exploration of abstraction in terms of color, or more accurately, in terms of the way in which she uses black and white to construct space (75). But O’Keeffe’s early abstractions construct space in other novel ways as well, suggesting close analogies to cloth, by pleating, folding, or crumpling forms.4

The self-conscious performance of being an “artist” has a longer genealogy than Corn addresses and one worth remembering. It is essentially a Romantic idea, and was already nearly a century old when adopted by modernist artist groups. One could open out the project, as Corn invites us, to consider Bauhaus, Die Brücke, and any number of contemporary groups. Suggestively too, the epigraph which stands at the head of the introduction, from Frances O’Brien in 1927, ends: “To her art is life, life is painting (9).” The echo of Robert Henri’s admonition is real. Corn focuses on Frida Kahlo as another example of how rewarding this enlarged focus can be, but, as she acknowledges, there could be many others.

O’Keeffe is an artist who makes many an art historian uncomfortable—she is too popular, not sufficiently dangerous, simply too much. Corn deliberately toys with that discomfort by ending the book with a serious discussion of O’Keeffe’s influence on fashion, and with an aside: that she realized she was rectifying a mistake in the literature by taking the discourse from public culture as seriously as she took art-historical perspectives. Corn rather cannily addresses and subsumes some of the vast literature on the material side of O’Keeffe’s life into academic scholarship (such as the houses—and here it should be mentioned that one of the things the book admirably succeeds in doing is assimilating a large body of separate studies of different aspects of O’Keeffe’s life, many produced by the O’Keeffe Museum). But there is so much more. As Corn notes, O’Keeffe was a serious cook, herbalist, and gardener. But she also was a serious hoarder of paint brushes and paint tubes, not to mention all the rocks, shells, and bones she placed on window sills. Where does one stop in studying O’Keeffe’s performance? It is tempting to end the review with an amusing quip about what we might look forward to: scholarly studies of O’Keeffe: Eating Modern, etc. But, here is where Corn and the great scholarship of her colleagues come into play: undergirding the book is the laborious effort of describing, analyzing, and cataloguing a large body of material artifacts. One of the great pleasures of material culture studies is that one can pay serious attention to any artifact and draw from it scholarship of interest and value. Food studies is a growing field, after all.

Corn has thrown down the gauntlet for us to return to artists we thought we knew well and discover the meanings of their archives in full. Marsden Hartley’s trinkets and Coptic textiles await the researcher at Bates College and the Beinecke Library, for example. What else is there for us to rediscover and consider?

Cite this article: Bruce Robertson, review of Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern, by Wanda M. Corn, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2282.

PDF: Robertson, review of Georgia O’Keeffe Living Modern

The Cleveland venue of this exhibition was reviewed in Issue 5.1 of Panorama. Please click here to read the review by Samantha Baskind.

- Wanda M. Corn and Tirza True Latimer, Seeing Gertrude Stein: Five Stories, exh. cat. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011). ↵

- See Barbara Haskell, ed., with contributions by Bruce Robertson, Elizabeth Hutton Turner, Barbara Buhler Lynes, and Sasha Nicholas, Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009). ↵

- Erin Coe, Gwendolyn Owens, and Bruce Robertson, Modern Nature: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2013). ↵

- See Robertson, “Useable Form: O’Keeffe’s Materials, Method, and Motifs,” in Haskell, Georgia O’Keeffe, 128-9. ↵

About the Author(s): Bruce Robertson is Professor Emeritus of the History of Art & Architecture and Director Emeritus of the Art, Design, & Architecture Museum at UC Santa Barbara