Mark Bradford: Pickett’s Charge

Curated by: Evelyn C. Hankins and Stéphane Aguin

Exhibition schedule: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, November 8, 2017–2021

Exhibition catalogue: Evelyn C. Hankins and Stéphane Aquin, Mark Bradford: Pickett’s Charge, exh. cat. Washington, DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, in association with Yale University Press, 2018. 82 pp.: illustrations (chiefly color). Hardcover $29.95 (ISBN: 9780300230772)

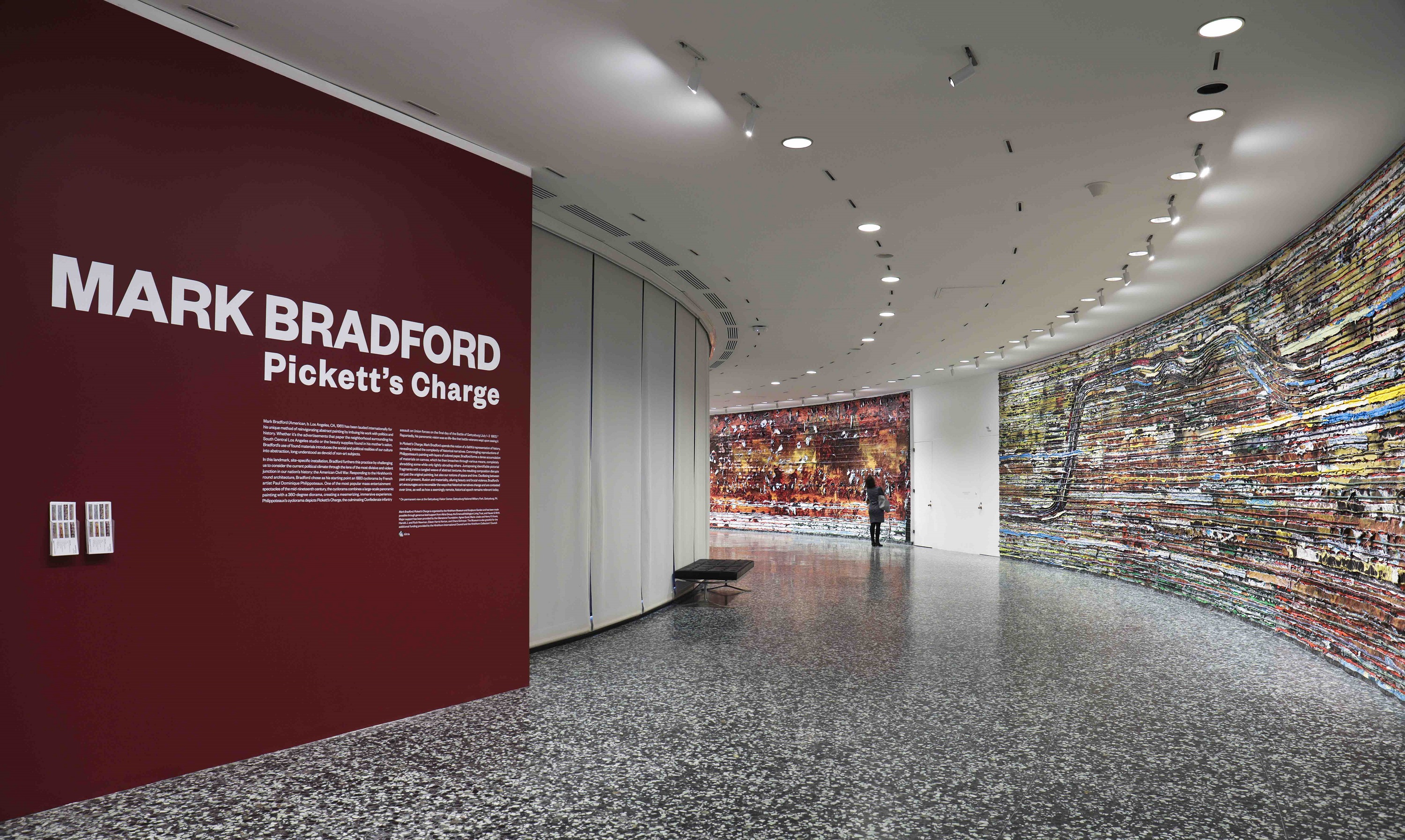

Mark Bradford (b. 1961) has solidified his position as a household name among art-going audiences in recent years. In the summer of 2017, the artist represented the United States at the American Pavilion during the Venice Biennale. Later that year, the Smithsonian Institution’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden opened an epic installation that runs until 2021. Titled Mark Bradford: Pickett’s Charge, the installation presents Bradford’s signature collage technique and highlights his penchant for oblique commentary on history, geography, and politics at a time when such discursive sites seem increasingly charged and contentious. For Pickett’s Charge, Bradford created eight large-scale panels, each twelve feet high and forty-five to fifty feet in length; the installation is a site-specific work that enters into a conversation with the Hirshhorn’s elevated, open cylinder structure (fig. 1). The work is based on Paul Dominique Philippoteaux’s (1846–1923) nineteenth-century Gettysburg Cyclorama (1883; Gettysburg National Military Park) depicting the pivotal moment in the Civil War battle when Confederate general George E. Pickett led a failed offensive against Union forces. For viewers traveling to the Hirshhorn Museum’s central location on the Washington Mall, in close proximity to the sites of so many recent political battles, Bradford’s installation presents a tongue-in-cheek interrogation of history, vision, and truth in the context of another critical crossroads in American history.

Bradford paints using a process of collage in which he builds layers of bright, vibrant pigmented paper, appropriated street posters, and other materials that are then manipulated through sanding, scoring, and tearing. Art historian Huey Copeland described Bradford’s compositions as suggesting “the historical, the cartographic, and the architectural while remaining resolutely abstract.”1 In Pickett’s Charge, the deep layers of colored paper are structured by lines of bungee cord or rope buried in the strata of color and material. They mostly run in regularly spaced bands parallel to the floor, although at times the regularity of these striations are broken as they swirl and wave across the canvas. The ropes are often pulled from their bedding in the canvas to reveal the layers of color below or to hang from the wall in messy, paper-coated tentacles. The deep troughs left by removed rope highlight the archeological nature of the work that sometimes invokes the peeling layers of postings and concert announcements on city streets, or neglected billboards. The work is recalcitrantly material, yet it contains moments of discernable imagery in the form of enlarged reproductions of Philippoteaux’s cyclorama, a scene only just discernable through the rips and seams of paper and rope. Instead of producing direct photographs of the painted cyclorama, Bradford culled these images from the internet and enlarged them to billboard-sized prints. The source images were apparently photographed from books, as the process of enlargement has exaggerated the overlapping Ben-Day dots from the CMYK printing process. These stages of mediation and manipulation, which Bradford does little to hide, add another layer of abstraction to the images in Pickett’s Charge.

Bradford’s choice to appropriate Philippoteaux’s 1883 Gettysburg Cyclorama is rooted in the artist’s recurring engagement with historical sources. For example, in 2014, he created a series of works based on Gustave Caillebotte’s canvas The Floor Scrapers (1875; Musée d’Orsay). The allusion to the Gettysburg Cyclorama presents a further engagement with modern notions of vision and history painting. Popular in the nineteenth century, cycloramas (or panoramas) were huge painting hybrids often presented in specially constructed buildings. Viewers entered the display via a passageway that went below the work and ascended to a viewing platform in the middle of the scene. Mimicking the construction of a panoptic prison, the viewers of these popular spectacles would survey the scene lit from a hidden window above. Philippoteaux was a well-known creator of such marvels, and his Gettysburg Cyclorama had a number of iterations. One version was exhibited in the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. The restored canvas on display today in Gettysburg was originally shown in Boston and is nearly four hundred feet in circumference and forty-two feet high. On the floor below the platform, earth and props were employed to blend seamlessly with the painted surface. Marveling at this nearly undiscernible blend of painting and prop, one nineteenth-century viewer wrote, “The visitor will miss much if he fails to notice this blending of the real and the illusory. And if he has never witnessed a battle, and has any desire to know what war in all its fearful reality is, he has only to look upon this wonderful picture.”2

Capitalizing on the unique architecture of the Hirshhorn Museum, Bradford adapts the cyclorama format for the twenty-first century in Pickett’s Charge. The massive yet intimate compositions cover the entire curving wall along the inner gallery of the third floor of the donut-shaped building, broken periodically by doorways into other galleries. The opposite wall of glass looks into the inner courtyard of the building. Given the plan of the Hirshhorn Museum, viewers cannot stand in the center of the installation to have one all-encompassing view of the work. The visual techniques of the cyclorama are thus disrupted. Of course, I could not help but imagine how, if the sheath of window shades were not lowered (which they were in my visits), one could look across the inner courtyard to Bradford’s work on the opposite side. Frustrated by the difficulty of this view, visitors must inevitably turn back to the work and, comparatively pressed against the canvas, they must move in either direction to follow the canvas curving out of view.

While perhaps initially frustrating, this difference from the experience of the cyclorama reflects some of the powerful critiques presented by Bradford’s play with the form. Philippoteaux’s viewers in the nineteenth century were engaging with new architectural technologies seen in iron buildings and new museological techniques seen in the proliferation of World’s Fairs, all brought together in the cyclorama form. For philosopher Walter Benjamin, such technologies mirrored the bourgeoisie’s celebration of its centrality in a new world order—gathering and organizing the world through commerce, display, and spectatorship. Referring to the fad of panoramas in Paris, he wrote,

The panoramas, which declare a revolution in the relation of art to technology, are at the same time an expression of a new feeling about life. The city dweller, whose political superiority over the country is expressed in many ways in the course of the century, attempts to introduce the countryside into the city.3

It is therefore no coincidence that curator Evelyn C. Hankins opens her catalogue essay on Pickett’s Charge with a quote from the theorist.4 Of course, Benjamin’s analysis probed Paris in the nineteenth century, and one must remain cognizant of how Philippoteaux applied the panorama as one tool in another struggle for mastery that was underway in America after the Civil War: that of overcoming the trauma of the Civil War and of writing the American narrative. Narrating the Civil War was a hugely important project just beginning to gain steam in the United Sates in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. This is reflected in other cultural productions, such as the increasing manufacture of Confederate monuments (plans for Richmond Virginia’s Monument Avenue were begun in the 1880s, and the famous Robert E. Lee monument was unveiled in 1890).5 Philippoteaux’s cyclorama presents the bloodiest moment of Civil War history as a frozen and controllable panorama—visitors witness but are never threatened by its unfolding chaos. The cyclorama in this respect was a technology of control over the world and over history.

Yet there is no controlling history in Bradford’s Pickett’s Charge. There is literally no stage for the centered subject and the masterful sort of viewer imagined by the nineteenth-century cycloramas. Bradford’s compositions do contain a few moments when images of the scene borrowed from Philippoteaux cohere; in these instances, one discerns representations of a haystack, pixilated soldiers armed and charging, or a pair of horsemen observing the battle. Still, these are brief glimpses of recognizable things, tentatively viewed through the striations of rope. At no time does one get the sense of the scene as a frozen moment in history. We are instead thrust into the event as layered, obscured, and impossibly mediated. These layers become the source of the work’s abstraction, and rather than using techniques to hide the illusion, viewers are confronted by the materiality of the work. Bradford’s abstraction is phenomenological, and one almost feels immersed in its materiality as the work literally peels off the wall into the viewer’s space. If history is a central theme of Pickett’s Charge, it is presented as the chaos of an all-encompassing process unfolding before us in physical form rather than in representation. Resolutely anti-monumental, Bradford presents us with history in the twenty-first century.

Of course, Bradford’s overwhelming abstraction is not without pleasure. The florescent yellows and blues and the sheer material nature of the work maintain a seductive sensuality. The abstracted scene could equally suggest a process of forgetting or provide a space for denial in which the implications of this intervention could be ignored, or at least muted, in favor of the pleasure of the work. If Pickett’s Charge has a message for us, it seems unclear, contingent, and unstable. This is not to say that the Hirshhorn has not made attempts to make the work and its implications accessible to the throngs of viewers that come through its doors every day. On my first visit to the exhibition, a gallery guide greeted viewers with an iPad in hand to provide information on the context of the work and to thus control its inscrutability. In later visits, the friendly gallery guide was gone, but beneath the title on the introductory wall, two prominently positioned pamphlet holders contained handouts with thumbnail illustrations and information on the installation. In addition, Chris Brenneman and Sue Boardman’s book, The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas, was placed on a number of gallery benches for curious or confused visitors.6

One provoking surprise for those looking closely is the fact that the informational handouts provided by the Hirshhorn Museum do not exactly coincide with the works on the walls. The haystack in the panel titled Dead Horse, for example, appeared significantly deteriorated in person, more so than in the illustrated materials. Clearly, the artist made adjustments sometime between the documentation of the work and its final installation—yet another example of the performative and improvisational aspect of Bradford’s process. But in my visits, I could not help but muse on the possibility of overzealous viewers pulling at the work. I was not alone in noticing the handout images as yet another divide between representation and reality in the exhibition. Recently, I had a conversation with a new acquaintance who had seen the exhibition and found the disparity somewhat unnerving. For her, the degrading haystack introduced a question of when or whether the work is complete.

Yet, in the end, we agreed that this evolving and unstable nature highlighted by the draping rope held exciting potential in its presentation of Pickett’s Charge. It perhaps suggested yet another way in which to critically alert viewers to the illusory representational techniques of Philippoteaux’s frozen battle scene. Pickett’s Charge insists that history is never complete. Without a doubt, the layers of interpretation produced by Philippoteaux and its various mediations inform our own embodied present. Today Americans live in times that are perhaps as confusing, chaotic, and fraught as they ever have been, and it is this condition that Pickett’s Charge seems driven to illustrate.

Cite this article: Tobias Wofford, review of Mark Bradford: Pickett’s Charge, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 2 (Fall 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1682.

PDF: Wofford, review of Mark Bradford

Notes

- Huey Copeland, “Painting After All: A Conversation with Mark Bradford,” Callaloo 37, no. 4 (Fall 2014): 814. ↵

- Rev. J. L. Harris, “The Battle of Gettysburg,” Zion’s Herald, March 18, 1885, 86. ↵

- Walter Benjamin, “Paris, the Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, ed. Peter Demetz, trans. Edmund Jephcott (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978), 150. ↵

- Hankins quotes Benjamin’s assessment of the panorama’s reworking of painting: “Just as architecture, with the first appearance of iron construction, begins to outgrow art, so does painting, in its turn, with the first appearance of panoramas.” Evelyn C. Hankins, “Mark Bradford: Into the Fray,” Mark Bradford: Pickett’s Charge, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, in association with Yale University Press, 2018), 1. ↵

- Melanie L. Buffington, “Stories in Stone: Investigating the Stories Behind the Sculptural Commemoration of the Confederacy,” Visual Inquiry: Learning & Teaching Art 2, no. 3 (2013): 299–312. ↵

- Chris Brenneman and Sue Boardman, The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Civil War (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2015). ↵

About the Author(s): Tobias Wofford is Assistant Professor in the Department of Art History at Virginia Commonwealth University