Marta Pérez García: Restos-Traces

PDF: Hanin, review of Marta Pérez García

Curated by: Vesela Sretenović, Director of Contemporary Art Initiatives and Academic Partnerships at The Phillips Collection

Exhibition Schedule: The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, March 31–August 28, 2022

Reviewed by: Mark L. Hanin

In the Restos-Traces exhibition at the Phillips Collection, Marta Pérez García explores the theme of domestic violence against women and children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Housed in a single gallery, the exhibition consists of a set of female torsos modeled after mannequins. Created from handmade paper with deft overlays of wire, nails, metal spikes, hair, teeth, and film negative, the works defy easy categorization and exist at the intersection of sculpture, assemblage, and craft. Most of the torsos hang from the ceiling, leaving just enough room for visitors to wander among them, an experience that is both effective and jarring (fig. 1). Restos-Traces is the thirty-first project in the Phillips Collection’s Intersections series, which was launched in 2009. Through this series, the museum invites contemporary artists specializing in a broad array of media to showcase works that engage with the museum’s architecture and/or permanent collection.1 Pérez García’s works are presented here alongside a painting by Francis Bacon and an installation piece by Annette Messager.

While Pérez García made thirty torsos as part of her Restos-Traces series, this show features nineteen pieces to highlight issues of violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United States, where one in four women experiences some form of intimate partner violence, the pandemic’s prolonged stay-at-home orders led to an 8.1 percent rise in domestic violence.2 The subjects of gender violence and domestic abuse, and the capacity of art to engage those topics in poignant and transformative ways for both survivors and society, have been central preoccupations of Pérez García’s work. Originally from Puerto Rico, Pérez García received her art education in the United States and works and lives in Washington, DC. She describes her art as striving to “create aesthetic spaces which shed light on the relationship between women and violence” and to “give a voice to women who have lived and continue to live in silence through . . . acts of abuse.”3

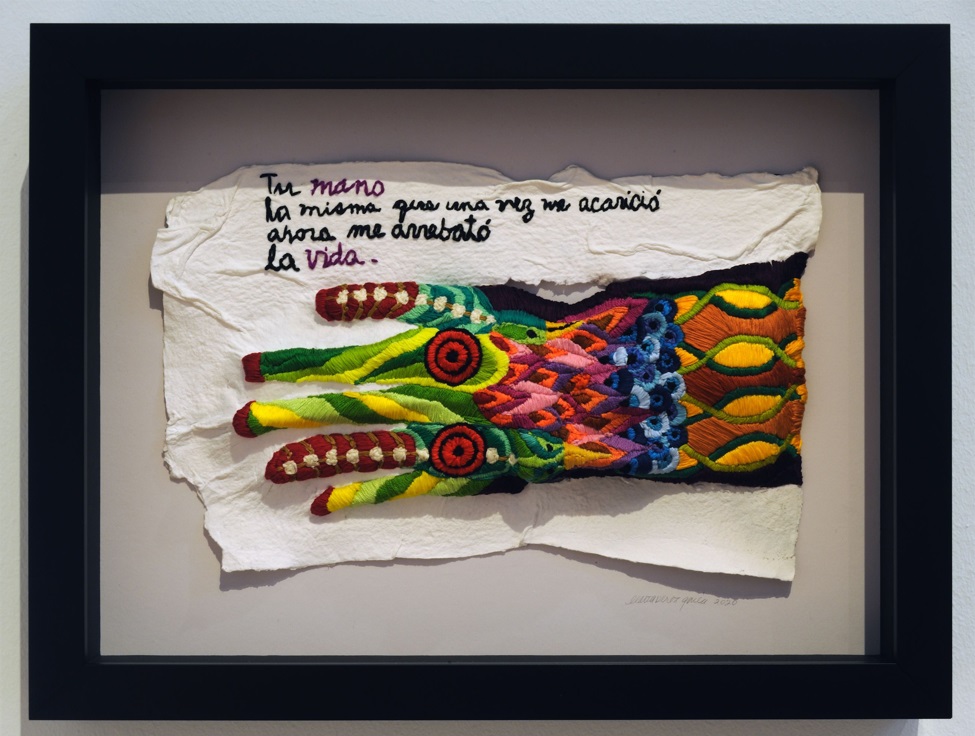

Pérez García works across a range of media, including woodprint, drawing, painting, tile, fabric, and found objects, as well as handmade paper and yarn. Many of her works feature bright palettes with bold primary colors, including reds, blues, yellows, and greens. Exemplifying these qualities, Tu mano (Your Hand) (2020), which the Phillips Collection recently acquired, bears the following inscription woven in black and purple yarn: “Your Hand, / The very one that once caressed me / Has now taken my life” (fig. 2).4 Indeed, many of the titles of her earlier works, including Me Desaparezco (My Disappearance) and Invisibles, point toward motifs and preoccupations that carry over to this show. The nearest precursor of the Restos-Traces series is Pérez García’s grant-funded 2018–20 project Si te cojo: Cuerpo, mujer, rotura (I’m gonna get you: Body, woman, rupture), which showcased more than 150 dolls made by survivors of domestic violence in workshops organized in partnership with the DC Coalition Against Domestic Violence.5 In the workshops, Pérez García asked participants to sew spines into the dolls as symbolic acts of regaining courage, which prompted some participants to break their silence about their experiences: “I never ask them to share their stories, but once we start making the dolls, they just open up.”6 Pérez García thus imbues her art with the dual functions of raising awareness about the scourge of domestic abuse—its profound toll on women’s bodies and psyches, as well as on entire communities—and, in a more hopeful or therapeutic vein, opening up opportunities for catharsis facilitated by art.

Restos-Traces fits recognizably within a tradition of art produced as a response to second-wave feminism. Begun in the early 1970s, this artistic movement broadly reacted to the dominance of mid-twentieth-century abstraction in art, championed largely by male artists, by turning the viewer’s attention back to embodied realities, including the humanity of the female body. This movement typically privileged mixed-media and installation projects that blended high art with crafts and deployed art to mount socially and politically salient critiques, including on issues of gender and women’s rights.7 In this vein, the Restos-Traces exhibition makes a tacit case for greater societal efforts to combat domestic abuse, bringing to mind ideas expressed by women’s rights advocate and abolitionist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In an 1892 speech in Washington, DC, titled “The Solitude of Self,” Cady Stanton argued that depriving women of educational, civic, and social opportunities is unethical and unjust because it renders women less equipped to confront life’s deepest existential challenges, which every person must ultimately face alone.8 Leveraging the visual medium, Pérez García makes a kindred case focused on the acute spiritual and physical burdens of domestic abuse, which disproportionately affect women.

In so doing, Pérez García implicitly points to a lacuna in Western art. While stories involving physical and sexual violence directed at women are often portrayed in European painting—from Titian’s The Rape of Europa (1559–62) and Tarquin and Lucretia (1571) to Nicolas Poussin’s The Abduction of the Sabine Women (probably 1633–34) and Guido Reni’s Susannah and the Elders (1620–25)—few contemporaneous works dwell on the aftereffects of sexual violence. How can this topic find expression in a contemporary visual medium?

Pérez García answers this question by playing on the relationship between image and text in various guises. The series title, Restos-Traces, fuses the Spanish word restos, which means remains or ruins, with the English word “traces.” When people experience abuse that leaves behind painful traces in their memories and bodily sensibilities, how does it alter their relationships with their bodies? How might a person’s inner self splinter off from an artificial, external persona shown to others? The word “person,” after all, comes from the Latin persona, which already connotes performativity and acting or, as Thomas Hobbes defines it, “the disguise, or outward appearance of a [person], counterfeited on the Stage,” including a mask worn over the face.9 Pérez García exploits the dualities of mind/body, interior/exterior, authenticity/performativity, and past/present to grapple with the theme of domestic violence through art.

The face is one of the most expressive parts of the body and is intimately tied to our identities. Yet faces are largely absent from the show. Anonymized bodies are instead the focus. None of the figures has a unique name. Each is simply titled Sin Nombre in Spanish (translatable as Untitled) or, perhaps more poignantly, Nameless in English, underscoring the prevalence of domestic abuse. Pérez García used mannequins as models for the torsos. Developed as part of the standardization of clothing sizes and ready-made ware, mannequins embody the role of display, specifically as lifeless, expressionless vessels used to showcase material goods. Subverting this generalization, Pérez García transforms the mannequin shells into sculptural figures that express a rage of potent psychological states. Seventeen of the torsos are suspended from the ceiling at slightly different angles, swaying as the air circulates. Two others stand on the gallery floor. Four torsos each have a single word inscribed in capital letters on their bodies: “SILENCIO,” “NO” (twice), and “INVISIBLE.”

The handmade paper used to construct the pieces has a highly textured quality, with countless topographical features, ridgelines, ripples, and minute variations. Consequently, the paper transcends the limits afforded by classical marble or stone. The dominant palette Pérez García employs to create the torsos is white, off-white, cream, and beige, complemented by elements of bluish-green, charcoal, black, and pink. Although the colors in this show are more muted than in her prior work (see fig. 2), the resulting figures are strikingly heterogeneous in their appearance and emotional register, from vulnerability, resignation, agony, and sensuality to vehemence and self-assertion. The combination of forthrightness, irreverence, and graphic bodily preoccupation in Restos-Traces has a kinship with the body-centered photographic oeuvre of Cuban artist Ana Mendieta (who herself may have been the victim of abuse by her partner, the artist Carl Andre10).

One common theme uniting the torsos is the centrality of spines and vertebrae. They play key compositional roles and are symbols of reaffirming self-esteem and physical integrity. Women scarred by domestic abuse, says Pérez García, “really need to be able to take possession of their bodies again.”11 This observation echoes the artist’s epigraph written on the gallery wall (fig. 3):

I inhabit this formless body, which not even paper can name. Memory mutilates it, the mirror destroys it. The gaze attacks it like a gunshot to a wounded animal. I disappear.

Me encuentro en este cuerpo sin forma que ni el papel lo reconoce. La memoria lo mutila, el espejo lo destruye. La mirada lo ataca como un disparo al animal herido, desaparezco.

These lines express a striking sense of dispossession and alienation from one’s own body as a consequence of abuse. The spines may thus act as a synecdoche for reconstituting the self, as in the doll-making workshop organized by Pérez García in her prior project Si te cojo. Each torso has carefully crafted vertebrae, some more anatomically realistic than others. In one case, pearls inlaid on a crimson background stand in for vertebrae, calling up associations both with glamour and violence. In another case, the vertebrae are represented by nails driven into soft brown material running up the back. Other figures have fantastical spinal columns with whimsically exaggerated vertebrae, bringing to mind conceptual drawings for theater costumes. Some take on impressionistic winglike shapes, evoking images of aerial nymphs in Renaissance art. And, in an eerie counterpoint, certain torsos have vertebrae-like elements on their chest cavities, with bony protrusions and dark, amorphous textures, vaguely reminiscent of Congolese nkisi n’kondi figures. The physicality of the torsos constructed from fragile paper—with a variety of openings, incisions, and decorative lattice-like patterns—blends into the empty spaces within and around the figures. It is almost as if the spirits of the torsos, dreaming to escape the confines of their suffering bodies, have a presence, hovering in the liminal spaces in and around the torsos. The interplay between materiality and void, the visible and invisible, permeates the gallery.

Consider the figure given pride of place in the alcove beneath the epigraph (see fig. 3). It has an elongated neckline, slender waist, and enlarged corset-like buttons at the front. A triangular incision is cut between the collarbones and breasts, bisected by a vertical line decorated with a heart.12 Playing on the adage of “looking into someone’s soul,” the incision opens up onto a spinal column with oversized vertebrae cascading downward. Beneath the ruffled peplum of the skirt emerges a conical, handmade wooden frame like a cage crinoline, a mainstay of nineteenth-century fashion to support dresswear, which often hemmed in and constricted the female body for the pleasure of the male gaze. Within the circumference formed by the cage crinoline on the floor, Pérez García arranged a heap of expressionless, masklike faces—as if the masks are linked to the torso’s identity, perhaps as haunting visages of its abusers or as alter egos of the victim herself (fig. 4).

The torsos portray a cross section of women at different stages of life, reflecting diverse sensibilities and relations to sexuality. Women who have experienced abuse “are not just survivors,” Pérez García emphasizes, but “[t]hey are moms, sisters, children, teachers. They are all of us.”13 One torso has a gaunt, even emaciated, appearance, with protruding ribs and pelvic bones. Other torsos of younger women are more sensual and sexualized, with formfitting clothes accentuating their figures. One such torso, dressed in white, depicts a young woman with a crucifix hanging askew on her chest. At whose hands did she experience abuse? Is Pérez García gesturing to the hypocrisies of the Catholic Church, given the abuse scandals that have emerged in the last twenty years?14 Two of the torsos appear pregnant, their abdomens featuring intricate ornamental incisions. Further complicating the role of fertility in women’s lives, one of the pregnant torsos has, in place of breasts, two enormous heads with mouths agape, as if to receive milk. Is this a commentary on the burdens of motherhood or on the inability to nourish a child because of the specter of abuse? Were these pregnancies wanted or the consequences of assault? These questions take on special significance in light of the US Supreme Court’s recent decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, which repudiated a Constitutional right to abortion and accelerated the passage of state laws restricting access to abortion.15

Further underlining motifs of sexuality, the torsos’ breasts and genitals are creatively embellished. Pérez García’s method of incorporating objects such as pearls, nails, spikes, and teeth to create an uncanny effect has an affinity with the ingeniously provocative work of contemporary artist Laura Kalman. Some breasts have ostentatious flourishes made of crumpled paper. Others are pointy and fierce. In one case, the breasts extrude dramatically from the body, emblazoned with dozens of metal spikes. Whether this militant posture is defensive or aggressive is left ambiguous. The figure’s genitals, too, have symbolic force, with floral elements that recall Georgia O’Keeffe’s work or vagina dentata representations, at once witty and jarring, almost at the risk of falling into bathos.

As a male viewer, I felt unease when meditating on the torsos, sometimes wishing to avert my gaze, as if to ward off vicarious shame for harms inflicted on women, typically by men. Viewing some torsos as sensual or attractive felt explicable but troubling. At the same time, reacting to elements of other torsos as off-putting in a visceral way was difficult to avoid; yet such a repellent response also seemed misplaced or even inappropriate. This perpetual discomfort about the ethical tenor of one’s reactions only reinforced the power of these figures.

Presented alongside the torsos are two works from the museum’s collection chosen by Pérez García in conversation with curator Vesela Sretenović: Francis Bacon’s Study of a Figure in a Landscape (1952) and Annette Messager’s installation piece Mes petites effigies (My little effigies) (1989–90). While Pérez García’s nineteen torsos are clustered together, they seem oblivious to each other’s presence, as if each is lost in its own world, much like the solitary figure in Bacon’s painting. Through his frequent portrayals of inchoate, masklike human forms, Bacon spoke to British society’s intolerance of homosexuality in the mid-twentieth century. In Figure in a Landscape, a man crouches warily amid a field of yellowish reeds, naked and without clear expression. Despite some obvious contrasts between Bacon’s and Pérez García’s art as to medium and thematics, the palpable sense of angst and contingency, along with an intense psychic struggle centered on sexuality and its social dimensions and implications, binds the works together.

By contrast, pairing Pérez García’s torsos with Messager’s Mes petites effigies illustrates how the two artists assign distinct functions to their art. Mes petites effigies consists of thirteen vignettes suspended from the wall at different heights. Each displays a small, eerie stuffed animal holding a decontextualized black-and-white photo of a body part next to a framed paper with one word written obsessively over and over in French—for example, “provocation,” “fear,” “treason,” “lying,” “scruple,” or “reconciliation”—rhyming with the one-word expressions on some of Pérez García’s torsos. Enigmatic and thought-provoking, Messager’s vignettes may allude to visions of romantic hope and its loss, physical and mental rupture, and doubts about whether a unified self can be attained, ideas that resonate with tensions in Pérez García’s work. But effigies externalize what society sees as evil, immoral, or corrupt onto objects that can be pilloried and mocked in a purgative fashion. Pérez García’s torsos, if anything, are anti–effigies. Rather than externalizing evil to purge it, they are created to externalize elements of one’s own self to reinfuse it with courage and strength.

Cite this article: Mark Hanin, review of Marta Pérez García: Restos-Traces, Phillips Collection, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15108.

Notes

For very helpful comments I am grateful to Monica Bravo, Brittany Wellner James, Vesela Sretenović, and the editors of Panorama.

- “The Phillips Collection Announces Spring/Summer 2021 Intersections Project,” Phillips Collection, April 5, 2021, https://www.phillipscollection.org/press/phillips-collection-announces-springsummer-2021-intersections-project. ↵

- “Fast Facts: Preventing Intimate Partner Violence,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last modified November 2, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html; Alex R. Piquero, Wesley G. Jennings, Erin Jemison, Catherine (Katie) Kaukinen, and Felicia Marie Knaul, Summary, “Domestic Violence During COVID-19: Evidence from a Systematic review and Meta-Analysis, National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice,” Council on Criminal Justice, February 2021, https://build.neoninspire.com/counciloncj/wp-content/uploads/sites/96/2021/07/Domestic-Violence-During-COVID-19-February-2021.pdf. ↵

- Marta Pérez García, NowBeHere, accessed September 17, 2022, https://nowbehereart.com/artist/marta-perez-garcia. ↵

- “The Phillips Collects: Marta Pérez García,” Experiment Station, Phillips Collection, December 17, 2021, https://blog.phillipscollection.org/2021/12/17/the-phillips-collects-marta-perez-garcia. ↵

- Marta Pérez García, “Installation: Marta Pérez García’s ‘Si Te Cojo . . . Cuerpo, Mujer, Rotura,’” Repeating Islands, August 24, 2019, https://repeatingislands.com/2019/08/24/installation-marta-perez-garcias-si-te-cojo-cuerpo-mujer-rotura; Stephanie Ramirez, “Local artist says DC is censoring her art exhibit on domestic violence,” WUSA9, October 16, 2018, https://www.wusa9.com/article/news/local/dc/local-artist-says-dc-is-censoring-her-art-exhibit-on-domestic-violence/65-605011033. ↵

- Andria Moore, “Local artist helps survivors share their stories in anti-domestic violence exhibit,” DC Line, September 17, 2018, https://thedcline.org/2018/09/17/local-artist-helps-survivors-share-their-stories-in-anti-domestic-violence-exhibit. ↵

- See Judith K. Brodsky and Ferris Olin, “Stepping out of the Beaten Path: Reassessing the Feminist Art Movement,” Signs 33, no. 2 (Winter 2008): 329–42. ↵

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, “The Solitude of Self,” in American Speeches: Political Oratory from Abraham Lincoln to Bill Clinton, ed. Ted Widmer (New York: Library of America, 2006), 99–109. ↵

- Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 112. ↵

- See Sean O’Hagan, “Ana Mendieta: Death of an artist foretold in blood,” Guardian, September 21, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/sep/22/ana-mendieta-artist-work-foretold-death. ↵

- Moore, “Local artist helps survivors share their stories in anti-domestic violence exhibit.” ↵

- Intentionally or not, the shape of the incision echoes certain nineteenth-century women’s fashion. See “Ball gown, c. 1842,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/155675. ↵

- Moore, “Local artist helps survivors share their stories in anti-domestic violence exhibit.” ↵

- See, for example, Tara Isabella Burton, “The decades-long Catholic priest child sex abuse crisis, explained,” Vox, September 4, 2018, https://www.vox.com/2018/9/4/17767744/catholic-child-clerical-sex-abuse-priest-pope-francis-crisis-explained. ↵

- See Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Org., no. 19-1392, 2022 WL 2276808 (U.S. June 24, 2022); Spencer Kimball, “Several U.S. states immediately ban abortion after Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade,” CNBC, June 25, 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/06/24/us-states-immediately-institute-abortion-bans-following-roe-ruling.html. ↵

About the Author(s): Dr. Mark L. Hanin is a Senior Associate at the law firm WilmerHale in Washington, DC.