Mosquitoes, Malaria, and Cold Butter: Discourses of Hygiene and Health in the Panama Canal Zone in the Early Twentieth Century

In a 1921 article enumerating the many successes of the Panama Canal since its opening six years earlier, geographer and editor R. H. Whitbeck described in triumphal terms what he called America’s transformation of the Panama Canal Zone:

Today the swamps are filled, the mosquitoes are gone, the streets are paved and clean, and the zone is as healthy as Massachusetts. This is what man has done at a place where geographical conditions induced him to build an interoceanic canal. It is an inspiring example of man’s conquest of adverse nature; not man’s response to a hostile environment, but his defiance of it and his subjugation of it; an example of so-called geographic control upon which is superimposed a still more impressive example of man’s control.1

Whitbeck’s soaring rhetoric of mastery paralleled contemporary perceptions of and reactions to the canal at the time of its completion. Moreover, it shared with other observers the prevailing assumption that the herculean task was enacted by a powerful, manly nation that transformed the vexing imperial problem of a hostile environment—the tropics—into a meaningful and coherent zone of progress, health, indeed civilization itself.

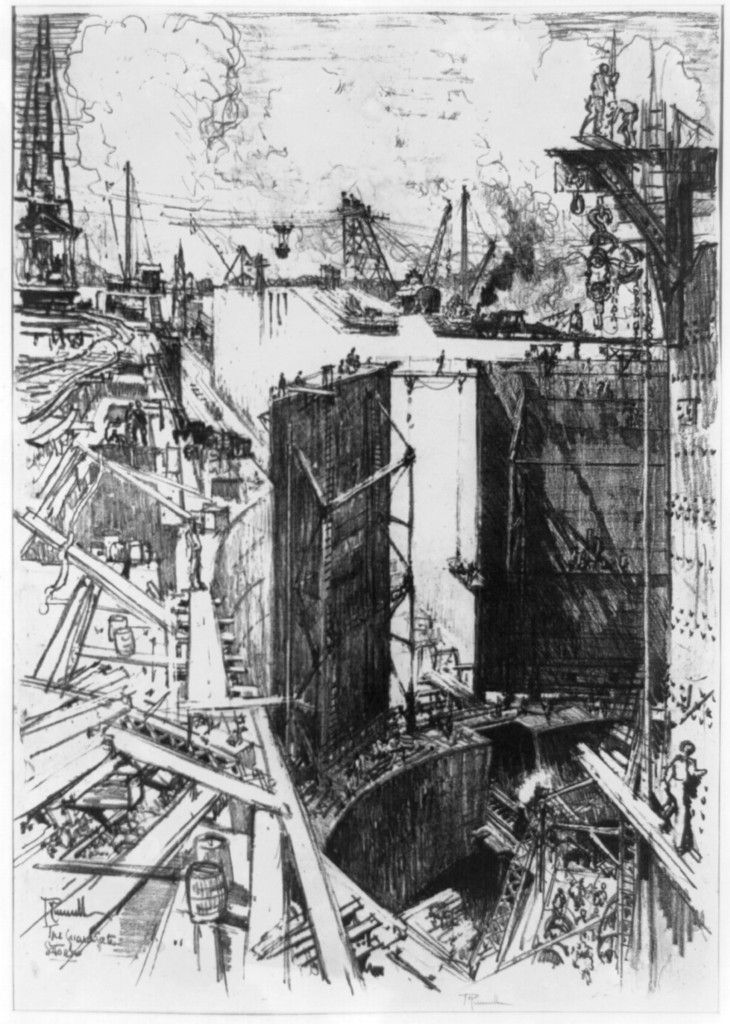

Contemporary visual images of the Panama Canal, almost without exception, were equally celebratory and affirmed the anthropocentrism of enterprise. Joseph Pennell (1857–1926), Alson Skinner Clark (1856-1949), and Jonas Lie (1880–1940), for example, traveled to the Canal Zone near the end of the construction phase and created images—lithographs and paintings—that canonized the epic nature of the engineering feat. Often utilizing a view from above—a common compositional strategy in nineteenth-century landscape painting to disclose the viewer’s privilege and dominance over a broad swath of land—Pennell and Lie conveyed the enormity and complexity of the canal project in their sublime images and defined them in equally epic terms: The Apotheosis of the Wonder of Work (by Pennell) and The Conquerors (by Lie) (figs. 1, 2).2

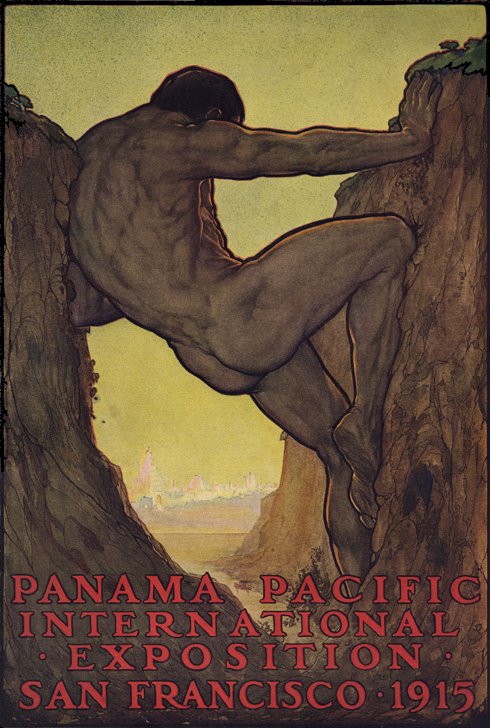

A particularly striking example of such celebratory images, and one that enjoyed wide circulation, is the official poster for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition held in San Francisco in 1915; the world’s fair was designed to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal. Thirteenth Labor of Hercules (fig. 3), by California artist Perham Nahl (the nephew of painter Charles Nahl, who traveled to the Panamanian isthmus in the 1860s), depicts a nude, hypermuscular male thrusting apart the continental barrier at the famed Culebra Cut—pushing back the forces of wilderness—to allow the seas to meet and give rise to civilization as evidenced, below Hercules’s feet, by the domes and pinnacles of the fairgrounds rising in the misty distance. Although previous world’s fairs in the United States employed a similar visual device for their publicity images—a representative figure of America gestures from above to a bird’s eye view of the fairgrounds below—Nahl’s gargantuan figure departs from the more common allegorical representation of the nation in the guise of a female figure such as Columbia or Liberty. Hercules is a modern hero/engineer whose prowess, healthful vigor, and supreme fitness are demonstrated by his ability to redeem and surmount the inefficient forces of nature and recreate it for his own needs. Indeed, the figure is an explicit expression of anthropocentric thinking that underscored the imperial project as a whole and assumed the supremacy of human needs and desires. This heroic superman embodies both the history of the United States and its taming of the frontier in the nineteenth century and its global future, naturalizing material evidence of the inevitability of American progress.3 Moreover, Nahl depicts Hercules as a discrete body, impenetrable to the forces of chaos and disorder—or mosquito bites, one imagines—and bound by distinct borders between subject (the imperial body) and object (the Panamanian landscape).

Indeed, the radical transformation of the land in Panama during the building of the canal was widely understood as the most magnificent modern expression of progress and civilization that has defined the complex relationship of America to nature since European colonists first encountered the North American continent. Moreover, it rendered in tons of concrete and steel the Cartesian dualism of nature and human being, itself at the root of anthropocentrism, seeing nature as something out there and into which civilization could and would encroach and triumph. Although its history as an imperialist project of continental expansion would not be fully addressed until several decades later, the global implications of the venture were noted by most.4

What most contemporary observers failed to consider, however, is what I would call the ecology of the project and the fact that the tropical environment was not only the most formidable and often lethal obstacle to its realization but also unstable, changing, and capable of producing change. To be sure, the geography and climate of the region were widely recognized as compromising the productivity of the venture. However, each was seen as a discrete location or definable problem that could be compartmentalized, measured, mapped, and otherwise contained so as to transform the tropics from a torrid zone to a temperate one. This so-called transformation of the tropics, however, was not a one-way street: transforming agent (United States technology) plus labor (largely West Indian) surmounts natural forces and objects (continental divide, torrential rains, mudslides, disease-carrying mosquitoes). Indeed, many of the objects against which the enterprise struggled—perhaps none more than the lowly mosquito—were transformative agents themselves that threatened the builders’ (real and imagined) efforts to separate themselves from the natural world.

In this essay, I would like to shift attention away from the building of the Panama Canal as an enactment of United States imperial prowess, technological know-how, and masculine chest beating—this terrain has been well covered by recent scholarship—and instead turn to the idea of the Panama Canal as a hybrid and shifting landscape, a zone in which the entanglements between human and nature as well as economy, technology, and politics proliferated and often contradicted one another. Despite material attempts to subdue the Panamanian landscape—both by the very act of physically cutting through the isthmus to make a canal and through the containment and eradication of disease—Panama’s non-human inhabitants proved to be stunningly resilient. Plants overgrew construction equipment, thwarted work, and complicated travel, while insects, particularly disease-carrying mosquitoes, proliferated in tropical humidity and migrated freely across spaces and bodies. The resulting hybrid landscape even created disease, facilitating the spread of malaria, although this reality was largely invisible in contemporary discussions and views of the region. Entrenched anthropocentrism disallowed even imagining nature as a potent agent.5

Following the lead of cultural historian Monique Allewaert in her work on what she calls the American Plantation Zone, I propose the term Panama Canal zone not as descriptive of a discrete place but constitutive of multiple interacting and overlapping systems.6 Discourses of health, hygiene, and progress—visual and textual—provide the primary metric with which to recalibrate thinking about the Panama Canal enterprise and zone as an ecology located at the nexus of intersecting discourses. To be sure, the Panama Canal zone—its landscape, technology, documentation, and human and nonhuman subjects—was managed by a powerful ideological and bureaucratic structure and an archive of visual images and written texts that valorized ideas about American ingenuity, progress, modernity, health, and superior fitness. At the same time, it is a fluid terrain—a borderland—that encourages the view of Nahl’s Hercules as an ecological body, instead of a discrete entity, just as is the water that passes through the canal: neither Atlantic nor Pacific but instead a hybrid, flowing across boundaries of all kinds.

Ecocriticism provides a transdisciplinary lens with which to compromise the long shadow cast by Cartesian dualisms and recalibrate critical understanding of the Panama Canal zone as an ecology in which an amalgam of interpenetrating forces—human, natural, insect, medical, vegetal, climatic, microbial—were entangled. Not simply an account of the so-called nature of the region, an examination of place, or an accounting of the “conjoined problems of economic and environmental exploitation,”7 an ecocritical reading interrogates how the human and nonhuman, corporeal and noncorporeal, organic and inorganic are entangled and amalgamate into a hybrid and unbound landscape that denies discrete borders between interior and exterior, subject and object, national and transnational. Instead of thinking of the Panama Canal region as an enclosed boundary, subject to technological, medical, and sanitary interventions from the outside, as well as aesthetic conventions that transformed the Panamanian isthmus into a landscape—a backdrop for human habitation and dominion—ecocriticism invites us to think of the Panama Canal zone as a set of relational media extending into, transformed by, and transforming events, places, and forces outside of it. Shifting away from the technological and medical heroism of modernization and disease eradication, and its fundamental anthropocentrism, interpretations of the zone in Panama can be interpreted as a “disaggregated and opened body” in light of environmental relationships, entanglements, and the agency of the nonhuman.8

“Rude Corner of the World”

President Theodore Roosevelt faced any number of obstacles between 1903 and 1904, vying for support of Congress and the nation to take on the enormous task of building the Panama Canal. Among those was the widely held and quite horrifying image of the canal zone as a formidable jungle of chaotic and inhospitable nature—distinctly outside of civilization, savage, and teaming with pestilence and danger—in the minds of Americans, most of whom had never set foot in Panama, by reports and images of visitors to the area. Noted author and editor James Anthony Froude wrote of Panama in 1885, “In all the world there is not perhaps concentrated in any single spot so much swindling and villainy, so much foul disease, such a hideous dung heap of physical and moral abomination.”9 Equally stinging were the words of Marie Gorgas, wife of the sanitation director, William Gorgas, regarding her husband’s first trip to the Canal Zone in March 1904. “Nature herself seems to have set aside the Isthmus as the headquarters of the worst manifestations of the human spirit.” She continued, “The whole forty-seven–mile stretch was one sweltering miasma of death and disease.”10 Gorgas’s remarks echoed a chorus of cautions about the hostile and vile nature of the tropical Isthmus, going back at least as far as the building of the Panama Railway in the 1850s. With the obvious reminders of the failed effort of France in the construction of the canal between 1880 and 1888, such as discarded machinery and numerous cemeteries—one doubter of the French effort noted in 1885 that “there will not be enough trees on the Isthmus to make crosses for the graves of your laborers”11—it is no wonder Roosevelt and the recently instituted Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC) recognized the gravity of the formidable task ahead and set their sights on sanitation and disease control as their first and most pressing issue in the Canal Zone.

No figure was more central to the early endeavor to combat disease in Panama than Army physician William Gorgas, whose efforts to eradicate yellow fever, malaria, and other diseases while recreating Panama as a modern and healthful environment, as defined by those living in temperate zones such as the United States and western Europe, were hailed as a fitting example of the civilizing force of the nation. Gorgas got his start fighting mosquitoes in Havana during and after the brief war with Spain and was the obvious choice to assemble an army of “health workers,” as they were known, to combat disease in the newest imperial arena of the United States. Gorgas believed he was restoring health and hygiene, indeed civilization, to this “rude corner of the world,” as he called the Panamanian tropics. His alignment of cleanliness, health, social discipline, and moral authority were not unprecedented, being invoked most recently in the American intervention in the Philippines following the Spanish-American War. The assumed racial superiority of the United States to enact this cleansing ritual—the “poetics of cleanliness” in the words of anthropologist Anne McClintock12—was clear in Gorgas’s 1909 article, “The Conquest of the Tropics for the White Race,” in which he likened the prevalence of disease in the jungle to what was widely perceived as indolence and barbarism in those native to the tropics.13

Many contemporary accounts included before-and-after descriptions and pictures that contrasted the depravity and lack of hygiene before the arrival of workers and engineers from the United States with clean cities, paved streets, bakeries, houses with screened windows, telephones, porcelain baths, and iceboxes owing to Gorgas and his army of health workers. A contemporary observer applauded the enormously successful transformation by Gorgas of the “most pestilential region on earth . . . into a practical winter health resort.”14 The modernity and civility of the canal zone, as a result of the United States sanitation efforts there, led one British tourist to remark, “Who ever heard of an American without an icebox? It is his country’s emblem. It asserts his nationality as conclusively as the Stars and Stripes afloat from this roof-tree, besides being much more useful in keeping his butter cool.”15 Implicit in such accounts is an anthropocentric and imperialist perspective on the enterprise.

The Trouble with the Tropics

At the turn of the twentieth century, tropical nature had become “a global and imperial environmental problem of the first order,” with the Panamanian isthmus as ground zero.16 Throughout the nineteenth century, the tropics were both an empirical fact—a geographical region of the world with mappable coordinates between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn (twelve degrees latitude north and south, respectively) and distinctive flora, fauna, and topographical details—and an imaginative construct that was defined as much by nostalgia, desires, and fears and as an identity counterpoint to everything the civilized world was not. Binary oppositions were routinely enlisted to define what was and was not the so-called torrid zone: wild/tame; uncivilized/civilized; humid/temperate; torpid/productive; slothful/energetic; south/north; unfamiliar/recognizable; illegible/decipherable; female/male; diseased/healthy; pestilential/paradisal. Moreover, during the course of the nineteenth century, the imagined tropics shifted dramatically from Humboldt’s richly detailed and aestheticized assessment of tropical abundance as a sublime landscape—a view that inspires terror and overwhelms rational assessment yet allows the viewer to see and experience fear without any actual danger—to a darker view of tropical nature defined by excess, degradation, disease, and resistance to the forces of civilization. This nature cannot be aestheticized and disarmed into a sublime landscape and refuses to be controlled by such human constructions.17 The presumption of environmental disorder extended to the inhabitants of the tropics who were widely discussed as racially inferior to those from more temperate zones. The assumed indolence and flaccid moral, mental, and physical tone of the native population were understood as evidence of their inferiority—a direct corollary to the vigor-sapping and morality-diminishing environmental effects of the tropics—and as justification for intervention from the outside.

Environmental historian David Arnold uses the term “tropicality” to discuss the discursive refashioning of the tropics—its landscape and inhabitants—at the turn of the twentieth century in response to, among other forces, the ideological imperatives of the imperial age.18 It can be argued that such ideological and representational shifts began a half century earlier, as the image of the tropics as a diseased and hostile environment was widely circulated by artists and writers following the discovery of gold in California, an episode that forever changed the United States engagement with the slender but recalcitrant isthmus in Panama.

“Beyond the Chagres River, All Paths Lead Straight to Hell!”

Although the story of nineteenth-century westward expansion is often conceptualized on an east-to-west trajectory, in fact the most practicable route between the east and west coasts was southerly, via Panama. One needs to remember that at mid-century, the territory west of the State of Missouri was often depicted as a blank space across which were printed the words, “Great American Desert.”19 And the four-to-five–month passage around Cape Horn—some fourteen thousand miles—was far too long for most impatient travelers and certainly for those seeking their fortune in California gold. By the late 1840s, the so-called Panama route was facilitated by two steamship lines operating between New York and San Francisco respectively; with the discovery of gold in California in 1849, demand on both lines increased dramatically.

The sixty-mile journey from the Caribbean to the city of Panama, on the Pacific, was not for the faint of heart. The first stage of the journey was made on the Chagres River, forty-odd miles, in wooden canoes propelled by native men using steering poles. In addition to the staggering heat and disease-carrying mosquitoes, the river swarmed with alligators, venomous snakes, and stretches of rough water. The final stage of the passage across the isthmus was on foot or on the back of a mule. The paths were narrow and swampy, often filled with mud due to incessant heavy rains. Contemporary descriptions underscored the wretchedness of the passage, including that by Frank Marryat, British sailor, artist, and writer, who traversed the Panamanian isthmus in 1850 on his way to California. His memoir of the journey, which was illustrated by the author, was published in 1855 in London and New York; his New York publisher, Harper and Brothers, printed a review of his book, including illustrations, in their periodical, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, assuring a wide readership.

Marryat’s narrative aligned with widely held perceptions of the future canal zone as the “foremost pest-hole of the earth, infamous for its fevers, and interesting only because of the variety of its malarial disorders and pestilences.”20 He described the town of Chagres, where the river passage begins: “The town of Chagres deserves notice, inasmuch as it is the birthplace of a malignant fever, that became excessively popular among California emigrants, many of whom have acknowledged the superiority of this malady by giving up the ghost a very few hours after landing.”21 His illustration Crossing the Isthmus (fig. 4) visually captures many of the hardships of the journey he described. Against an impenetrable jungle backdrop complete with jagged rocky peaks, a precipitous crevasse, palm trees entangled with vines, and incongruous cacti are vignettes of hapless foreign travelers, utterly ill-equipped for the journey across the jungle—some on foot, others on mules up to their bellies in mud, still others wrestling with or having been bucked off their obstinate mounts. In contrast with the fully dressed Anglo travelers, including one woman—referencing the anticipated domestication of the region—four Panamanian natives, dressed in loincloths, conform to widely held racial stereotypes; the male figure in the background gestures violently, aligning his behavior with the wildness of the jungle in which he is embedded.

The eye moves across the image from right to left, as do the Anglo travelers and their pack mules that struggle with their heavy parcels. One such creature has stumbled on the rocky terrain, and its parcel, clearly marked with the instructions “This Side Up,” lists precipitously. Two travelers depicted in small scale are being transported in makeshift chairs strapped to the backs of native men. This rather perplexing section of the image may allude to the fact that outsiders depended on the local knowledge and willingness of native inhabitants to successfully navigate the challenging terrain; this seems to contradict contemporary viewers’ knee-jerk alignment of tropical natives with the chaotic landscape. Two dogs accompany the travelers in the foreground; their partial domestication contrasts dramatically with the wildness of the scene, including its native inhabitants, and, if obliquely, disrupts the defining binary quality of the image. This image was reprinted in a number of texts on the history of the Panama Canal written during the first two decades of the twentieth century, suggesting its visual currency as a marker of the canal zone prior to its transformation into a region of hygiene, progress, and civilization. Moreover, it contrasts dramatically with the bird’s eye views that would come to define i

- Ray Hughes Whitbeck, “Geography and Man at Panama,” Bulletin of the Geographical Society of Philadelphia 19 (1921): 8. ↵

- See, for example, Joseph Pennell, Joseph Pennell’s Pictures of the Panama Canal (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1913), 9; and Oh Panama! Jonas Lie Paints the Panama Canal (Yonkers: Hudson River Museum, 2016). ↵

- For a fuller discussion of this image see Sarah J. Moore, Empire on Display: San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013), 169–89. ↵

- See, for example, Amy Kaplan and Donald E. Pease, eds., Cultures of U.S. Imperialism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993); Walter LaFeber, The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1963); Paul S. Sutter, “Tropical Conquest and the Rise of the Environmental Management State: The Case of U.S. Sanitary Efforts in Panama,” in Colonial Crucible: Empire in the Making of the Modern American State, eds. Alfred W. McCoy and Francisco A. Scarano (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009), 317–26, 605–6. ↵

- For ecocriticism and the hybrid landscape, see Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010); Stehen Frenkel, “Jungle Stories: North American Representations of Tropical Panama,” Geographical Review 86, no. 3 (July 1996 ): 317–33; Alan C. Braddock, “From Nature to Ecology: The Emergence of Ecocritical Art History,” in A Companion to American Art, eds. John Davis, Jennifer A. Greenhill, and Jason D. LaFountain (West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2015), 447–67; Timothy Morton, Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007); Richard White, “From Wilderness to Hybrid Landscapes: The Cultural Turn in Environmental History,” The Historian (2004): 557–64; William Cronon, ed., Uncommmon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996). ↵

- Monique Allewaert, Ariel’s Ecology: Plantations, Personhood, and Colonialism in the American Tropics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 29, 195. ↵

- Ibid., 18. ↵

- Ibid., 19. ↵

- Cited in John M. Gibson, Physician to the World: The Life of General William C. Gorgas (Durham: Duke University Press, 1950), 97. ↵

- Marie D. Gorgas and Burton J. Hendrick, William Crawford Gorgas: His Life and Work (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page, 1924), 139–40. ↵

- Gibson, Physician to the World: The Life of General William C. Gorgas, 97. ↵

- Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Conquest (New York: Routledge, 1995), 226. ↵

- William Gorgas, “The Conquest of the Tropics for the White Race: President’s Address at the Sixteenth Annual Session of the American Medical Association, June 9, 1909,” Journal of the American Medical Association 52 (1909): 1967–69. ↵

- Charles Francis Adams, The Panama Canal Zone: An Epochal Event in Sanitation (Boston, 1911), 26. ↵

- Winifred James, The Mulberry Tree (London: Chapman and Hall, 1913), 226. See also Sutter, “Tropical Conquest and the Rise of the Environmental Management State,” 318. ↵

- Sutter, “Tropical Conquest and the Rise of the Environmental Management State,” 318. See also Stephen Jay Gould, “Church, Humboldt, and Darwin: The Tension and Harmony of Art and Science,” in Frederic Edwin Church, ed. Franklin Kelly (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1989), 94–125. ↵

- Katherine Emma Manthorne, Tropical Renaissance: North American Artists Exploring Latin America, 1839–1879, New Directions in American Art (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989). See also David Arnold, The Problem of Nature: Environment, Culture, and European Expansion (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996), 141–68. ↵

- Nancy Leys Stepan, Picturing Tropical Nature (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001). ↵

- Sarah J. Moore, “‘The Great American Desert Is No More’: Mapping Progress and the American West at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition,” in The Trans-Mississippi Exposition of 1898: Art, Anthropology, and Popular Culture, ed. Wendy Katz (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 240–75. ↵

- Adams, The Panama Canal Zone: An Epochal Event in Sanitation, 5. ↵

- Frank Marryat, Mountains and Molehills; Or Recollections of a Burnt Journal (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1855), 2. ↵

About the Author(s): Sarah J. Moore is Professor of Art History at the University of Arizona.