Of Masks, Mockery, and Modernism: Alexander Z. Kruse’s Self-Portrait of an Art Critic

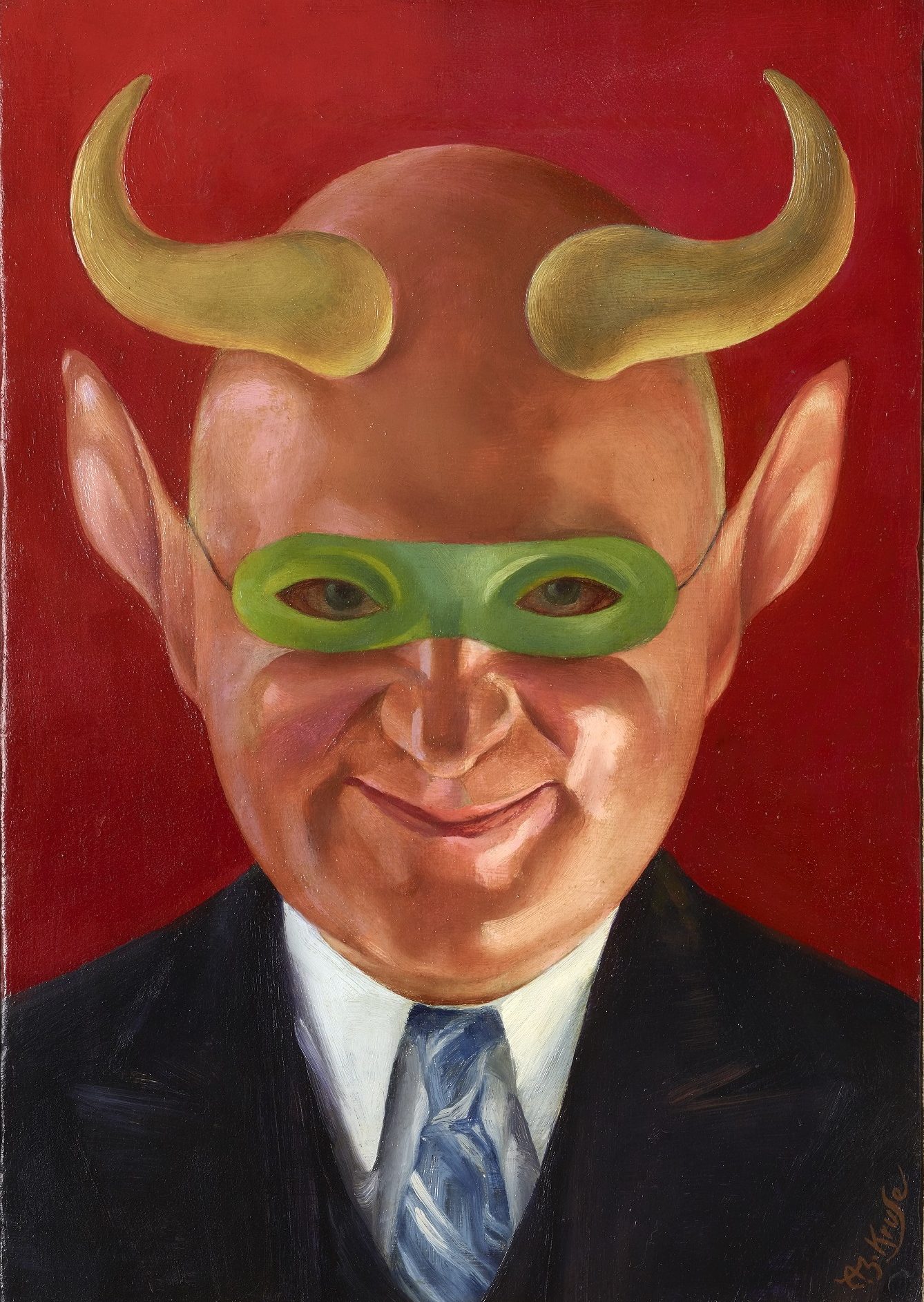

In 1936, during his third year as a critic at Art Digest, Alexander Z. Kruse (1888–1972) painted a self-portrait that alluded to the prominent role he held (fig. 1).1 Appropriately titled Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, the painting shows Kruse in a conservative suit and blue striped tie, on the surface irreconcilable with the yellow horns, elongated ears, green domino mask, and his impish grin, against a vivid red background. This startling full-frontal portrait, painted in high-key color and comprising incongruous imagery, begs us to ask: Why would the writer, painter, printmaker, lecturer, entrepreneur, critic, and teacher depict himself as such a hybrid and mischievous creature? How does Kruse’s self-fashioning relate to his art criticism, which distinguished him as an acerbic wit and clever commentator? Kruse, acclaimed and influential in his own day but now forgotten, wrote irreverent reviews and presented cheeky public lectures, unsparing of even the most lauded artists and movements of his time. On Pablo Picasso, Kruse quipped: “It is lucky that Picasso, with his uncontrollable urge for dynamic design experimentation, is an artist instead of a surgeon.”2

This essay explores Kruse’s use of humor in his art criticism and self-representation, considers how and why both aspects of his work relate to America’s enthusiasm for caricature during the interwar years, and examines how an artist adept with mass media and speaking to broad audiences engaged caricature and publicity to combat his fraught status in the art world. As is true of most caricature, Self-Portrait of an Art Critic requires the viewer to discern the true character of its subject through parodied referents, but Kruse also assists the viewer by providing a script for the painting—his often whimsical and outrageous reviews. Not only does Kruse unite the fine arts with de rigueur caricature, he appropriates other in-vogue forms of 1930s culture—the domino mask and a penchant for lightheartedness, humor, and ridicule—and it is this environment that fostered Kruse’s canvas. In doing so, Kruse attempts to advertise his work in both fields in which he practiced—the production and criticism of art. At the same time, he also advertised himself. Investigating the influence of caricature on Kruse’s work and the use of this dominant trend as a vehicle for publicity allows us to parse the two-fold position of the artist-critic. By revealing the parity of the narrative and painterly methods he employs we can by extension also understand how Kruse’s visual and written work, codified in Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, speak to the artistic moment when many of his contemporaries, critics and artists, were beginning to favor avant-garde art.

Kruse, whose training, art, and art criticism intersect with some of the most celebrated and influential early twentieth-century artists, was first and foremost a showman. An unabashed character bursting with personality, Kruse took center stage at nearly any opportunity. He studied and socialized with leading artists in New York, personally knew a number of eminent performers and thinkers, and aspired to be all of the above. Well recognized but working on the fringe of major success, Kruse calculated nearly every move he made to gain attention for his writing, his art, and even his inventions, which include a patented stapling machine for securing cardboard boxes. He authored a posthumously published semi-autobiographical novel, East of Broadway (1993), and two books for amateur artists: How to Draw and Paint (1953), comprising 164 illustrations and which sold more than three hundred thousand copies, and The ABC of Pencil Drawing (1956). Kruse was known in New York for his portrait demonstrations, where he would lecture on art while making a likeness of an audience member. An advertisement for the lectures describes Kruse as a “distinguished American Artist [who] has captivated the art lecture field with the same imagination he has displayed in his masterpieces in exhibition [sic] around the world.”3

Kruse was tremendously adept at making opportunities for himself. The same year he completed Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, Kruse orchestrated a commission to paint a canvas of Mayor LaGuardia. During the summer of 1935, LaGuardia conducted the Goldman Band in Central Park. Spurred by this popular public event, sensing an occasion for publicity, and in appreciation of LaGuardia’s support of the arts, Kruse conceived the idea to paint a portrait of the mayor and secured a commission from the head of the New York City Music Project, which was indeed covered by the press, to do just that.4 Unrealized ventures include a television show geared to the beginner artist (c. 1963) bearing the proposed titles “T.V. Art Studio” or “Hopalong Hobby Artist.” Kruse also tried to write, with his wife Anna, a newspaper column for the “30 million American men and women of 55 plus years.”5

After painting and printmaking, Kruse’s most consistent endeavor was art criticism. His magazine work began at the New Masses, where he served as art editor after World War I, following his mentor John Sloan’s earlier tenure in the same role at The Masses, the periodical’s predecessor. Strongly ambitious, Kruse took the position because of the publication’s prestige and its connection to Sloan, whom he deeply admired. The magazine’s leftist political stance piqued Kruse’s interest to a much lesser degree, and he did not use art to express an aggressive political agenda save for two extant anti-fascist paintings, discussed below, and a now-lost canvas addressing the fraught Sacco and Vanzetti case6 Unlike that of peers such as William Gropper, Kruse’s disposition was much too sunny to be embroiled in politics. For Kruse, the enemy was the art world that spurned him, rather than the fascist enemy. Celebrity caricature, the genre that inspired his self-portrait, was a neutral artistic language—a mode for humor and respite—divorced from the political concerns of the day. It was undemanding and fun, not rife for misinterpretation, such as Regionalism, which some connected to the chauvinistic nationalism of Nazi art.7

The years 1934 to 1939 mark Kruse’s initial foray as an art critic, when he wrote a column for Art Digest titled “Art to Heart Talks.”8 From September 1939 to 1946, Kruse penned a Sunday art column for the Brooklyn Eagle, and on June 26, 1949, the New York Post began running his “Art with a Small ‘a,’” an instructional commentary for amateur artists in the paper’s weekend magazine. In an article introducing the column, writer Wambly Bald described Kruse as a “jovial” and “genial, paint-splattered artist,” and Kruse wittily summarized the venture: “Art, like sex, is here to stay. But now everybody is getting into the act.”9

Kruse was trained by Ashcan artists Robert Henri, George Luks, and John Sloan at the Art Students League; however, he primarily worked as a printmaker in the 1920s and 1930s and was represented by the Weyhe Gallery. The early 1930s were Kruse’s heyday, when in 1932, The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired six prints; two lithographs were included in the Whitney Museum biennial exhibition (1933–34); and eight paintings were chosen for a Brooklyn Museum exhibition of painting and sculpture (1934), which were among over a dozen other showings. Kruse was well-enough known to have works acquired, in later years, for the permanent collections of major art museums, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Private collectors Alfred Stieglitz and Bernard Berenson owned Kruse’s art as well. To that end, a side goal of this article is to resurrect a once-prominent but now mostly neglected artist and critic.

Kruse took after his teachers by creating art in a realist mode, although in his case sometimes infused with humor. Kruse’s lithograph Back from the Country (fig. 2) for example, reproduced in the New York Evening Post and the Chicago Evening Post and shown at the 1930 exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists held at the Grand Central Palace, depicts a well-to-do woman weighing herself after returning from an indulgent vacation. Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, painted with oil and tempera, more forcefully adopts caricature, a mode by then also prevalent in Kruse’s art criticism.

In a survey of American graphic humor from 1933, a book with which Kruse may have been familiar, William Murrell describes caricature as “a satiric exposing of individual physical peculiarities and idiosyncrasies of manner, and its success depends wholly upon the psychological penetration of the artist. Diminution and exaggeration are among the most effective means employed. All caricature is inseparably shot through with irreverence . . . a caricature presents someone or something ridiculed.”10 Murrell delineates the essential components of caricature—irreverence, satire, and exaggeration—qualities Kruse deployed strategically in his work. Later in his book, Murrell usefully points to the history of caricature as a graphic art form, which changes in the early 1930s, an important development that influences Kruse’s self-portrait.

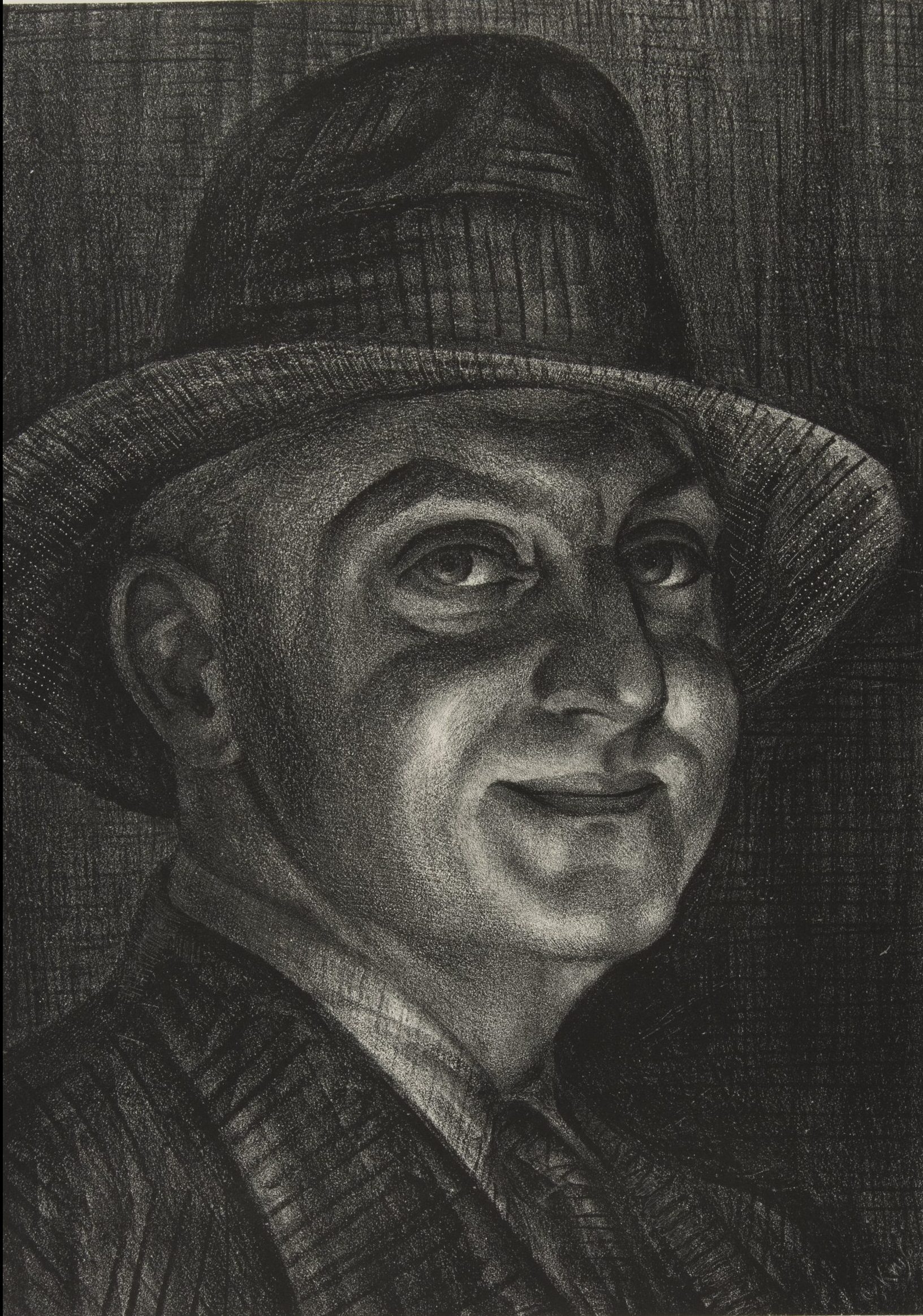

E. H. Gombrich’s short book on caricature understands such work as teaching the viewer to see the sitter “anew, to see him as a ridiculous creature. This is at bottom the true and hidden aim behind the caricaturist’s art. He is a dangerous fellow; his work is still somewhat akin to black magic. With a few strokes he may unmask the public hero, belittle his pretensions, and make a laughing stock of him.11” Gombrich points out the power of the caricaturist to unmask the public hero, but Kruse seems to be doing the converse: masking the reviled devil. Through a combination of a red, hell-fire background, a sinister smirk, and dangerous horns, Kruse constructs the artist-critic as a satanic figure, tightly cropped to maximize the menacing effect and the viewer’s encounter with the man-animal. Kruse skews his physiognomy by accentuating his cheekbones, chin, and forehead, which he bathes in a campfire glow, and he transforms his entire head into an oversized egg-shape, in contrast with his pointed, extended ears. And then there is the mask, a cover typically worn on the face to disguise the identity of the wearer or to transform the wearer into someone else by providing an alternate identification. Kruse submits an identity markedly different than that which we recognize in other self-portraits made throughout his life. Self-Portrait of an Art Critic contrasts with other self-images created early in his career (figs. 3, 4), which offer realistic views of the artist hewing closely to conventional standards of representational portraiture. In the 1936 self-portrait, Kruse obviously plays a role, in this instance enacting the part of his personality that fuels his success as an art critic. Yet Kruse’s primary vocation, that of a painter, is the means by which he renders his message, and therefore viewers must reconcile the binary position of the artist-critic as divine-devil. The striking masked creature that Kruse depicts may actually be more revelatory than the undisguised man portrayed in his other self-portraits.

Caricature and the Theater

During the interwar period, when caricature was at a peak of popularity, magazines such as the New Yorker, Arts, and Vanity Fair frequently published the work of Al Hirschfeld, Miguel Covarrubias, and William Auerbach-Levy, among others. Caricaturists were especially enamored with Hollywood glamour and theatrical subjects, a natural byproduct of the period’s particular fascination with celebrity.12 Celebrities appreciated the value of caricature, relishing likenesses of themselves along with attributes easily identified by an entertainment-conscious public. To be caricatured meant that one had achieved a degree of fame; if one can be recognized in a distorted portrait, then one unquestionably held celebrity appeal. Marius de Zayas, Ralph Barton, and Al Frueh made their careers by playfully picturing thespians in periodicals, and the walls of Sardi’s restaurant, opened in 1927, featured caricatures of show business figures, bringing the many dimensions of caricature to a New York audience who may not have been readers of sophisticated newspapers and magazines (Hollywood’s Brown Derby showed caricatures on its walls as well). Not only was Kruse’s devilish mid-1930s self-portrait shaped by the artistic tenor of the day and the performative nature of caricature and its connection to performers, it had roots in his own background in the theater, predisposing him to see self-representation in terms of performance.

Theater permeated several aspects of Kruse’s life. Born in New York to a poor Jewish immigrant family, at seventeen years old, Kruse worked for Oscar Hammerstein, who was a friend of his father’s, painting scenery for a musical theater production. When not making scenery, Kruse sketched the actors around him, but he had theatrical inclinations years before this early job. In a diary written late in life, Kruse remembered “play acting” with his childhood contemporaries. He described a “make-believe stage” in a friend’s backyard and the clever use of an outhouse for reserved seating. As a boy, Kruse and his friends Eddie Cantor and Willie Howard would place papier-mâché masks over egg-shaped constructions and impersonate ventriloquists.13 Cantor and Howard, who would later go on to become stars, were not the only future performers in Kruse’s life. He went to school in New York on the Lower East Side with vaudevillian Joe Cooper, composer Irving Berlin, and actor Edward G. Robinson. These early encounters encouraged Kruse, as a young printmaker, to favor theatrical subjects such as Musical Clown (fig. 5), depicting a jokester overwhelmed by his large sousaphone, which first was shown in the exhibition Fifty Prints of the Year, organized in 1930, by John Sloan for the American Institute of Graphic Arts. Paintings and prints from the time Kruse worked for Hammerstein engage similar material: Music Hall, Ted Lewis shows Lewis playing his instrument with one hand while gracefully standing in an arabesque (fig. 6). He commands the intensely lit stage in his blue costume with the audience featured in the foreground, watching from a balcony at left and lining the bottom as the orchestra plays below. Music Hall, Ted Lewis employs a strong artificial spotlight, a recurrent characteristic of Kruse’s work that, when staging Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, is used to particularly dramatic effect.

What is more, philosophically Kruse saw art as entertainment. In an undated note Kruse wrote, “[that] art functions as entertainment is undeniable. As a matter of fact when the generals of the army want to get the minds of the captive army off the sense of fear and fright they furnish them with brief periods of Entertainment.”14 Both Kruse’s writing and his art furnished entertainment for his audience; his success as an art commentator and his well-known portrait presentations made him something of a celebrity in New York. The March 15, 1941, issue of Art Digest published a caricature by Al Hirschfeld of the members of the self-proclaimed “Art Critics Circle,” New York’s most influential art critics, who gathered sporadically for luncheons to partake in friendly verbal jousting about art (fig. 7). Rendered with an economical use of line and a fair amount of exaggeration, Kruse sits on the right side of the table with his signature round glasses and an even rounder face, his small chin almost subsumed into his bloated neck.15 The publicity-conscious Kruse must have been delighted to be caricatured by such a well-regarded cartoonist and in the company of his esteemed peers.

Self-Portrait of an Art Critic predates a different kind of advertisement featuring Kruse. Showcasing his role as a painter, not a critic, Kruse appears in an advertisement for Mussini paintbrushes in the April 1940 issue of Parnassus (fig. 8) that highlights the artist in front of his LaGuardia portrait. Here, a smiling Kruse sanctions the product and, because he was viewed as important enough to endorse the brushes, Mussini sanctions Kruse (although notice that the artist’s surname is spelled incorrectly in the text below the picture, which also includes the major museums that hold his work). A little over a decade earlier, Kruse made a different appearance in one of John Sloan’s most recognized canvases, painted in multiple versions, McSorley’s Cats (fig. 9). Sloan sits at the lower left with glasses and a pipe, while Kruse is the central figure, posed in character as a distinguished, portly patron with a bowler and cane.

Kruse, the entertainer, provided opportunities for laughter in the form of slapstick written critiques and paintings such as Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, which New York Times critic Howard Devree called “libelously amusing” in his Sunday, April 27, 1941, column. Devree saw the work in a Kruse retrospective, held in New York at Wally Findlay Galleries, an exhibition that consisted of eighty-two works, thirty of which were prints, and termed the show “a laudable full-length report of personal achievement.”16 Kruse’s first solo exhibition in seven years was also well reviewed by Art Digest critic Helen Boswell, who remarked on his “amusing notes from Brooklyn . . . side-glance type of wit . . . and long associat(ion) with important names in art.”17

Kruse’s Disdain for Modernism

Kruse’s self-portrait is directly connected to his views on modernism, which he understood as art that deviated from a naturalistic representation of the world in favor of a proliferation of “isms” and experimentation, modes he felt were cheap, inauthentic, and inferior. This was especially pronounced when he perceived that an artist was hiding behind artistic “fads,” as he put it, because of a lack of skill to paint otherwise. As Kruse wrote in “Art to Heart Talks” the year before he painted his self-portrait: “Propagandistic dilettantes, who can neither paint, draw, design nor create, try to hide behind some political ‘ism’ in order to conceal their lack of ability as artists.”18 A month later Kruse riffed on the same issue: “A violin, not made of the right kind of wood and with sound considerations excluded from its construction, will not have any additional value in a hundred years, nor even a thousand. So it is with anxious writers on art who suffer from chronic poverty of thought. . . . Their mental make-up, like the common wood of the cheap violin, never improves.”19 The introduction to How to Draw and Paint contains a comparable comment for Kruse’s beginner artist audience: “One of the purposes of this book is to start the amateur artist in the right direction by teaching him the fundamental principles of art and by not allowing him to succumb to fads prematurely. It is important for ‘hobby artists’ to remember that artistic fads come and go.”20 It did not matter to Kruse that Picasso, for example, knew how to draw; that Picasso chose not to use his training was enough to pique Kruse’s sensibilities. Unlike his contemporary Thomas Hart Benton, who asserted his distaste for modern art even as he was still influenced by it, throughout his life Kruse remained staunchly resistant to almost all forms of modernism.

To convey his anti-modernist perspective, Kruse used written humor in his penned reviews, an approach akin to caricature. He adopted forms of exaggeration and distortion, as demonstrated by his commentary on Picasso, where he twisted the Cubist’s style into a joke.21 Consistently degrading modern art and promoting representational art, Kruse’s criticism often begins or ends with a punch line. In 1934, he wrote: “A rose is a rose because it is not a daisy; and a daisy is a daisy because it is not a rose. And just as there is a difference between a beer stein, a Holstein and a Gert Stein, so is there a difference between a modernist, an ultra-modernist and a faddist.”22 This excerpt, from Kruse’s first year as an art critic in his Art Digest column “Art to Heart Talks,” plays on the German word “stein,” and appropriates American expatriate writer Gertrude Stein’s language for his own purpose. As the short column continues, Kruse’s turn from jocularity to a serious tone reveals his opinion of modernism: “The artist of today, who is willing and self-satisfied enough to paint in the tradition of the popular discordant art fad of the moment, must of necessity pattern his mental make-up after the method used by the popular song writer or ballyhoo lecturer. He must keep abreast of the changing fetish of novelty in art, closely watching the aesthetic chameleon, performing a constant transition in point of view to suit the current fabricated fashion in art.”23 Kruse, in various forums, culminating with his painted critique in Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, made no bones about his belief in the limits of modern art.

As did many other realist artists, Kruse hoped that modern art was a passing trend; he used the word “fad” in three of the above commentaries. From the outset of his career as a critic he took artists that he viewed as modernists to task. His first Art Digest entry, dated April 15, 1934, bears the title “How Luks Explained It,” and relays an incident from his days in the classroom: “On one occasion, when Luks passed before the class, we were all startled by the sound of a crash of things tumbling, rolling, breaking their way down the stairway. With his usual spontaneous humor, Luks had the mystery solved. He said, with a wave of his hand and a snap of his finger: ‘Nothing to get frightened about—that’s just one of Max Weber’s abstract ideas falling down the stairs.’ It had been Weber’s first season as an instructor at the Art Students League.”24 Here Kruse appropriates Luks, along with Luks’s joke, to his cause.

On the subject of stairs, Kruse’s response to the threat of avant-garde art is analogous to the widespread outrage over Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912; Philadelphia Museum of Art) when it hung in the Armory Show. Now the stuff of legend, one critic ridiculed Duchamp’s canvas by likening it to “an explosion in a shingle factory”; former president Theodore Roosevelt mocked the painting by comparing it unfavorably to “the far more satisfactory” Navajo rug in his bathroom; and a cartoonist for the Evening Sun caricatured the painting as “The Rude Descending the Staircase (Rush Hour at the Subway).”25 This earlier use of humor to deflate, diminish, and critique Duchamp’s art, and the Armory Show as a whole, served as a valuable model for Kruse’s own brand of criticism, but even more, his quips and puns were inspired by the success of the sharp, stinging wit of the Algonquin Round Table writers.26

The Algonquin Round Table writers famously met for daily informal lunches at one o’clock at the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street in New York from 1919 through the early 1930s. Members of the group, dubbed The Vicious Circle—which included columnist Heywood Broun and Dorothy Parker, who wrote for Vanity Fair—were appreciated for their cultural and intellectual wit.27 Their wisecracks as well as caricatures of the group, both as a whole and as individuals, were published regularly in newspaper columns. Writings by Robert Benchley, an Algonquin member, essayist for the New Yorker, and editor of Vanity Fair, share a particular kinship with Kruse’s mode of commentary. In “Wear-Out-A-Shoe Week,” Benchley subversively asks, “Why are economists always so concerned with shoes? It amounts to fetishism. When they want to make a point it is always illustrated by the number of pairs of shoes that a given number of people will wear out over a given period. Just as in the old arithmetics it was always that A and B were sawing wood or swimming up-stream, in practical economic problems it is always that shoes are being worn out. Doesn’t anyone ever care about socks?”28 Kruse, always fond of the punchline, deployed his final jab at Max Weber—via Luks or not—in much the same way.

Dorothy Parker’s caustic humor was particularly renowned, with numerous victims the butt of her trenchant jokes. A woman once approached the Round Table, congratulating herself on the duration of her marriage. “I’ve kept him these seven years!” the woman bragged. To which Parker replied, “Don’t worry, if you keep him long enough he’ll come back in style.”29 Algonquin member Edna Ferber remembered the group’s particular gripe against “charlatans” in her autobiography, A Peculiar Treasure (1939): “The talk actually was witty, frequently biting and brutal. . . . They were ruthless toward charlatans, toward the pompous and the mentally and artistic dishonest.”30 Even though Kruse did not skew his victims for casual pleasure—as did the sharp-tongued Parker, Ferber, and others—his writings maintained a similar edge. Furthermore, Kruse also saved his most cutting remarks for those he viewed as charlatans or, as he put it, “faddists.”

At the same time that the Algonquin pundits’ irreverence was featured in sophisticated publications, humor also received pride of place in magazines devoted solely to joking and fun. Ballyhoo ran monthly from August 1931 to February 1939 (briefly published again from 1953 to 1954 as a quarterly), selling one hundred and fifty thousand copies of its first issue in only three days; the magazine met with such success that the print run for its sixth issue reached nearly two million31 The back cover of the magazine announced that the periodical was “Kept fresh by cellophane,” and the inside was filled with cartoons. Burlesques commonly parodied advertisements, and the final issue of Ballyhoo (February 1939) lampooned Life with a mock-up of the magazine. Anthologies also offered humor in various forms, including Wyndham Lewis and Charles Lee’s The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse (1930), with an index and editorial remarks even funnier than the bloated and corny poetry contained within the covers.32 Martha Bensley Bruère and Mary Ritter Beard’s volume Laughing Their Way: Women’s Humor in America (1934) debunked the notion that women are not funny by presenting readers with a selection of amusing prose, verse, and drawings.33

It was around this time that Constance Rourke’s pioneering and best-selling study on American humor (1931), vis-à-vis character types in literature, drama, and poetry, made the bestseller list, demonstrating strong interest in humor’s manifestations on native soil. Six years later, Walter Blair’s Native American Humor (1800–1900) tackled the subject from a more scholarly perspective while also reprinting a diverse range of source material, ranging from the Farmer’s Almanac to formal literature.34 Interest in humor grew during the Great Depression, when comedy and laughter served as a form of escapism and at times a mode of mocking commentary on the hardships of the moment. In the case of Kruse, his penchant for humor predated the nation’s economic challenges, and his jokes never directly addressed them.35 Nevertheless, the national predilection for at least a temporary panacea from the country’s ills was at a peak during Kruse’s prime. Humor flourished in words and images in the 1930s, and Kruse unites those fashionable manners of expression—caricature and humor in art and writing—in a dual treatise when his self-portrait and art criticism are viewed together.36 Kruse’s distaste for modernist trends and the facetious way he describes art help clarify his ideological stance as an art critic, but these factors do not fully clarify why he painted himself as such a devilish creature.

Who Was that Masked (Horned) Man?

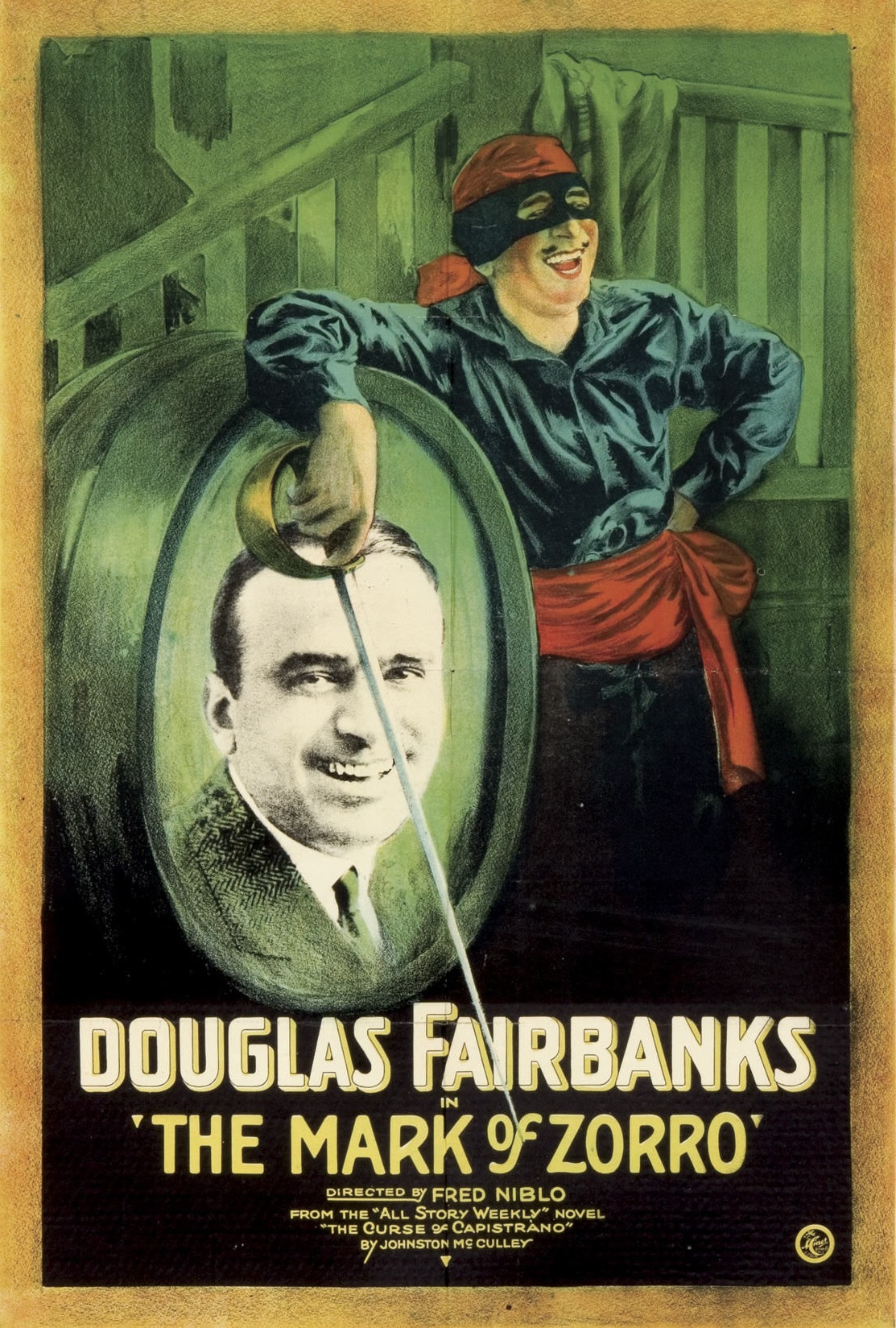

During this period, a number of prominent characters in popular culture were shown in domino masks, a successor to the half masks that covered the eyes and noses of commedia dell’arte actors in the Renaissance. The Lone Ranger, who wore a domino mask to conceal his identity from the Bush Cavendish Gang, premiered January 30, 1933, on Detroit radio, and soon became a well-recognized symbol of justice. The first Lone Ranger novel reached publication the year of Kruse’s painting, with the main character in his domino mask on the cover, and eighteen volumes followed from 1936 to 1956. The Domino Lady, whose moniker derives from her mask, was the heroine of six stories published from May to November of the same year that Kruse painted his self-portrait. This magazine serial told the story of Ellen Patrick, a beautiful woman sworn to avenge the assassination of her politician father. Along with high heels and a purse, Patrick wore a sleek, backless halter dress, gloves, and a domino mask to conceal her identity as she committed her justifiable crimes. Each month the fashion queen appeared on the magazine cover wearing her black mask (fig. 10). Zorro, the secret identity of Spanish nobleman Don Diego de la Vega, who fought political tyranny in early California, wore a long cape and a black face covering: in this case, a variation of the domino mask. The costumed swordsman who slashed his trademark letter “Z” on his defeated opponents originated in the 1919 serialized novel The Curse of Capistrano, written by Johnston McCulley. The silent film The Mark of Zorro (1920; fig. 11) starred Douglas Fairbanks, and Zorro graced the silver screen in 1936—again the year of Kruse’s painting—in the first color film by Republic Pictures, The Bold Caballero (fig. 12). Posters for both adopted the garish colorization that Kruse employed in his self-portrait, advertising films in which the clever, brave, and funny Zorro swashbuckled his way into viewers’ hearts as he fearlessly saved his cherished city, San Juan Capistrano, from ruin. The emergence of these masked avengers at the moment Kruse painted his enigmatic self-portrait suggests that popular imagery of the day influenced his conception, one that can best be explained by a twofold interpretation of the artist’s attempt to convey his twofold status as an artist-critic.

Between the wars, many American caricaturists moved away from the traditional line drawings of late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European caricaturists such as George Cruickshank and Thomas Rowlandson, and earlier work by Americans, such as Thomas Nast, whose cartoons were published in periodicals including Puck, Judge, and Harper’s Weekly. Already used by Vanity Fair artists following a design initiative in the late 1920s, the vibrant colors found in advertising prompted caricaturists’ bold use of color.37 Color’s prominence in caricature increased during the 1930s, bolstered by the popularity of cartoon movies and the influence of modern art, and further influenced Kruse’s vivid self-presentation.38 Not only does the polarity of the man-animal in a professional suit capture the eye, but so do the vibrant red background, yellow carnivalesque horns, and chartreuse mask, especially in contrast to the plastic, fleshy sheen of Kruse’s shadowed face and bald pate. Press caricaturists of this period often utilized this kind of lively color. To name one example, Paolo Garretto’s caricature of Josephine Baker for the cover of the February 1936 issue of Vanity Fair presents the lithe dancer and singer against a bright yellow curtain (fig. 13). Using the stylistic forms typical of caricature in the press in conjunction with popular iconography, Kruse shows himself as a kind of superhero in oil—a champion, if you will, of the underdog artist. Kruse’s resemblance as an art critic avenger—in the same vein as the masked Lone Ranger, the Domino Lady, and Zorro—emerges because of his own empathy for the artist’s plight, which he translated into his art criticism.

Kruse’s mask, however, does not function as a full disguise. Even if Kruse’s name does not appear in the title of the painting, he clearly announces the work as a self-portrait, and his signature lines the bottom right corner of the canvas. His propensity for performance even finds its way into the signature, which is applied with theatrical flourish. The “S” in Kruse, worn near his label like a nametag, almost acts as the artist’s own Zorro-like insignia, although here marked on the portrait subject rather than a vanquished foe.39 Indeed, Kruse the art critic aspired to be clever, brave, and funny, sometimes tinged with aggression, as is acknowledged by the artist in his use of dangerous horns, like those of a bull waiting to attack.

Kruse again exploited the dangerous quality of horns the following year in the service of caustic commentary, this time of a political ilk. In the provocative protest painting Espanolaphone (fig. 14), one of the artist’s few expressions of political engagement, Kruse depicts a menacing Benito Mussolini in the company of a melodramatic Adolf Hitler wearing a clown suit marked by swastikas. Mussolini speaks to Hitler through the horn of a green bull, a key symbol of Spain transformed into a telephone, with the Führer receiving Il Duce’s message though the bull’s metamorphosed tail. A ruddy-skinned, satanic-looking Mussolini is outfitted in a blue full-body costume, topped by more horns and animal-like ears, smaller than those of the art critic but noticeably similar in shape. Behind the fascist pair, a graveyard visible through the window reveals the deadly outcome of their support of the Spanish Civil War. Espanolaphone, a highly theatrical conception, establishes Kruse’s rarely visualized political sympathies and belief in art as a tool for political change, likely fostered by his work at the New Masses. Paired with Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, the canvas also demonstrates the artist’s iconographic repertoire and continuing interest in caricature. It is the liberation experienced through role-playing, the unrestrained behavior in which Kruse indulges through his subversive art critic persona, which prompted his written art critiques. With the mask, horns, and other accoutrements removed, Kruse once more becomes a genial, paint-splattered artist. But when wearing the mask, his alter ego as a fighter against modernism emerges.

Kruse’s Disdain for Art Critics

Kruse viewed most art critics as harsh and disapproving cultural authorities who had no right to cast judgment. As an art critic himself, he knew that some saw him as a devil; the subjective aspersions of a critic possessed the ability to wound. No matter a critic’s preference, whether an advocate of realism or abstraction, Kruse believed that critical commentary could be validated only when the arbiter wore, as he did, two hats. As he wrote in “Art to Heart Talks”:

He who never does anything never makes any mistakes. The reason why so many of the cuttingly critical in print never produce any bad paintings is due to the fact that they never paint. The enlightened art critic of today, with his highly developed sensitiveness, has grasped the full significance of the art of criticism. Therefore, he looks at the silver lining inside of the clouds-upon-clouds of art production, until he finds virtues that over-shadow the many faults of many artists.40

Only as both artist and critic, claimed Kruse, would the reviewer’s sensitivity be heightened, and could he develop an eye for what he was judging.

As far back as the Italian Renaissance, Giorgio Vasari worked as both an artist and art critic, but over the course of history few have attempted, or at least found success, straddling both sides of the fence. In the first half of the twentieth century, however, a number of American artists made names for themselves in both fields. Henry McBride of The Dial and the New York Sun; Guy Pène du Bois, editor of Arts and Decoration; Louis Lozowick, who published in arts based venues as well as leftist periodicals like The Nation; Albert Gallatin, whose vast oeuvre includes art criticism in the New York Times and more than twenty monographs, including a volume on James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s caricatures; and Walter Pach, widely published and especially known for Ananias, or the False Artist, his indictment of opportunistic artists, occupied that ambiguous space between critic and artist, but they are among only a few that, like Kruse, fit into this category. One important critic of the time took a different stance. New York Herald Tribune writer Royal Cortissoz felt that artists could not be critics because they lacked objectivity, instead criticizing “in the light of what they have themselves done.”41 Kruse’s peers recognized his twin position in reviews. Robert Francis of the Brooklyn Eagle observed, under the headline “Practices What He Preaches—Eagle Critic Has Own Show,” that the Wally Findlay Galleries exhibition gave “his fellow artists an opportunity to see how he has applied his advice to his own efforts,” and Emily Genauer of the New York World Telegram noted, “an art critic’s a brave man to exhibit his own paintings in a public gallery.”42 Margaret Breuning of the New York Journal-American praised Kruse’s Findlay Galleries exhibition, affirming that “critical writing has not impaired his creative energy.”43 Critic-artist Ralph Flint, who wrote the exhibition catalogue foreword, asserted that the exhibition “seems to prove once more that this two-sided program of practising as well as preaching painting is a thoroughly rewarding one. That it brings a double return on the original investment . . . Alexander Kruse is once again on the air with pertinent observations on how a critic thinks in terms of line and color.”44

Kruse was not alone in his artistic contempt for critics who were not artists. Arthur Dove’s The Critic (1925), a collage portrait of Cortissoz, communicates a similar message (fig. 15), albeit from a position within the avant-garde. Wittily mixing materials, including newspaper clippings of art reviews, cord, and fabric, Dove ridicules this advocate of realism. The conservative Cortissoz emphatically preferred representational art; among the artists he supported were Thomas Eakins, Pène du Bois, and Luks, whose names pepper Dove’s collage. Cortissoz described his approach to criticism: “As an art critic I have been a ‘square shooter’ . . . I have been a traditionalist, steadfastly opposed to the inadequacies and bizarre eccentricities of modernism.”45 Standing rigidly at the front of the work as a showman in a top hat, and with a monocle hanging limply around his neck, the faceless critic in Dove’s work is therefore eyeless, blind, and incapable of sound judgment. Dove may have taken his inspiration from the title of the Dada magazine The Blindman, published just twice in 1917, which features a drawing on the cover, by caricaturist Alfred Frueh, of a blind man walking past a modern work of art. Dove further ridicules Cortissoz by having him stand uncertainly on roller skates, trying to maintain his balance by steadying himself on a vacuum cleaner rather than a cane. Such bad choices, like the decision to promote realism, were surely worthy of mockery. In contrast, caricaturist Peggy Bacon’s 1931 portrait of critic Henry McBride seems tame (fig. 16). An advocate for modernism beginning with his reviews of the Armory Show, McBride, who taught a teenaged Kruse at the Educational Alliance, is portrayed as a cultured and sophisticated gentleman enjoying his afternoon tea. Set against red, as in the creature in Kruse’s painting, McBride’s backdrop functions as a refined velvet curtain instead of a suggestion of hell-fire.

Other artists shared Kruse’s preference for the artist-critic. In September 1947, Kruse received a letter from artist Maurice Kish, thanking him for his art criticism, which is worth quoting:

I always admire your brave fight for the sincere and talented artist who does not care to become an “ultra-modernist,” but rather tries to create in his individual style, in spite of the “opinions” of the so-called ultra art critics who despise everything which resembles nature.

Another thing which I appreciate and admire, is your artistic eye. Since you are a fine painter yourself, you were never fooled by those who looked for quick recognition by becoming “abstractionists,” “primitives” and distorters of nature. . . .

If the so-called “ultra” art critics, who know so little about practical art, could know the pain of the artist before he finally succeeds in creating a real work of art, they would be more sincere and careful in their art criticism. . . .

I hope that all the “charlatans,” “clowns” and “freaks” who have penetrated the world of art, will be exposed for what they are, and their so called “art” will be thrown in the ash heap. I hope too, that some of the “blind” art critics will open their eyes to the real, true art, and to the artist who is fighting the uphill fight.

Perhaps the day is not too far off when a new renaissance will be born, and the world will know who the true artist is, and who the “charlatan.”46

Kish believed that Kruse’s dual standing encouraged his sensitivity to realism and his “brave fight” against modernism, as opposed to “‘blind’ art critics,” like that found in Dove’s portrait. An obviously frustrated Kish casts many aspersions in his scathing commentary; uses the word “charlatan,” as did Edna Ferber in her assessment of those she felt ill-equipped to render judgment; and adopts superhero language to describe Kruse. Kish’s negative reaction to art criticism is consonant with Kruse’s painted discourse on art criticism/art critics, although Kruse makes his points with sly wit to somewhat moderate his aggression. To that end, Kruse was generally a well-regarded art critic, although at times his humor can distract readers from his larger points. As much as he dug his feet into the mud on modernism, at its best his art criticism can be clever and insightful, and his art incisive, lending further credence to the importance of reconsidering his body of work.47

Kruse never backed down from his role as a critic-avenger with a devilish streak, entrenched in a valiant fight against modernism, whereas Pène du Bois had second thoughts. Looking back at his early art criticism, Pène du Bois wrote in his 1940 autobiography that he would “think twice about the manner of my attack. I might even have a fleeting moment in which I would consider behaving like a gentleman, although such an attitude in art and criticism is untenable.” Pène du Bois further recalled, “sometimes my victims were irate, sending me letters usually written in the heedlessness of reflex action.”48 Realist artists such as Kish, on the other hand, wrote thank you notes to Kruse for his art criticism. Amid modernist proponents such as Henry McBride, Lena Gurr also found Kruse to be a blessing. She wrote a letter to the editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on May 4, 1945, praising Kruse: “My fellow artists join me in my great appreciation for the splendid art criticisms of A. Z. Kruse appearing in your Sunday editions.”49

Even if Kruse presents his case against modernism in a more toned-down manner than Kish, the artist’s verbal jokes, while enjoyed by his audience as a form of entertainment, are still distinguished by an underlying combativeness, as signified in the self-portrait by Kruse’s horns. In his influential work Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, Sigmund Freud identifies humor as a form of aggression: “There are only two purposes that it [a joke] may serve. . . . It is either a hostile joke (serving the purpose of aggressiveness, satire, or defence) or an obscene joke (serving the purpose of exposure).”50 Cultural critic Gershom Legman similarly describes the joke, using language that intersects with Kruse’s iconography: “Under the mask of humor, our society allows infinite aggressions, by everyone against everyone. In the culminating laugh, by the listener or observer . . . the teller of the joke betrays his hidden hostility and signals his victory.”51 Under the mask of humor, Kruse’s aggressions certainly do emerge as a form of entertainment, his frustrations securely acted out because he is viewed as a showman. His verbal pronouncements, or denouncements, on modernism are more indicative of his jokester personality than of unbridled criticism of his contemporaries. Through jocularity in both print and paint, Kruse freed himself from the restrictions of his standing as a member of an artistic community to which he wanted to belong. Kruse’s joking playfulness, promoting his artistic ideals, also addressed the rising insecurities of realist artists, as especially demonstrated by Kish’s troubled letter, written as modernism began to dominate the art world.

While Kruse did show regularly in the 1930s and his work was sponsored by the Works Progress Administration, his insecurities were surely on the rise. His art was receiving little attention compared to his teachers, the artist’s measuring stick and tough shoes to fill; his wife was forced to take job as a keypuncher to help support the family; and the press frequently degraded realism. While some favorable reviews nodded toward Kruse’s ability to achieve humor in his art, more often he received only a glance from critics, and his work was not selling at a pace to sustain a living. Edward Alden Jewell’s January 4, 1932, column describing the exhibition A Chapter in Art at the Rehn Galleries provides an example. Jewell favorably mentions John Carroll’s Mother and Children as a “worthy addition” to his oeuvre, “marvelously integrated” and “beautiful”; Eugene Speicher’s Emigrant as memorable; and George Biddle’s Paper Flowers and South Carolina Landscape as “delightful.”52 Jewell also praises Sloan, Reginald Marsh, and Bacon (Kruse studied alongside Marsh and Bacon in Sloan’s art classes), but Kruse merely occupies a list of other artists who contributed to the exhibition, none of whose works were singled out as commendable. Still, there were moments of acclaim and hope. Small reproductions of his work appeared in many periodicals, including the New York Evening Post (1930), Pencil Points (1930, 1933, and 1935), Arts Weekly (1932), Creative Art (1933), Studio News (1933), and Art Digest (1932, 1933, and 1935). A delicately rendered drawn portrait by Kruse served as the frontispiece for a volume about French poet and writer André Spire (fig. 17).53 Most prominently, in 1935, Frank Nankivell wrote a one-page article in Prints magazine dedicated to Kruse, wherein he praised the artist’s “simplicity of expression . . . delight in pattern . . . and subtle sense of humor.”54

A Critic in Donkey’s Clothing

Kruse’s Janus-faced self-portrait, with its extremely unusual iconographic juxtapositions, features donkey ears, long associated with human beings to manifest stupidity. In showing himself as an ass, Kruse follows in a tradition of using animal symbolism to convey human imperfections. Such attitudes find form in various sources, including the ancient legend of King Midas (recalled in diverse texts, such as Ovid’s Metamorphoses XI, 165–216; dramatized by John Lyly in 1592, 4.1.149–50). Midas, the ruler of Phrygia, possessed the ability to turn all he touched into gold. This seemingly fortuitous gift was the result of a wish granted by Bacchus, who wanted to thank the king for rescuing his friend Silenus. Midas’s choice turned out to be a poor one; when the king became hungry and thirsty he could not meet those needs because food and drink changed to gold upon his touch. Even when servants tried to feed Midas, his lips metamorphosed sustenance into the intractable ore. Realizing that his wish was not judicious, Midas begged Bacchus to relieve him from his “gift.” The story demonstrates that Midas was not a very wise king, also illustrated by the second part of the tale, one in which Midas’s poor judgment, as in the poor judgment displayed by some art critics, is underscored again. Legend has it that as a judge between Apollo, the god of music, and the satyr Pan, Midas bestowed preference on Pan. The insulted Apollo then transformed Midas’s ears into those of a donkey for choosing foolishly.

Erasmus’s The Praise of Folly (1511), a book Kruse owned and annotated, also comments on the fatuity of man. Employing donkey symbolism, Erasmus notes that those disguised as “the ass in a lion’s skin” will ultimately be exposed as fools, for “the tips of their Midas-ears sooner or later slip out.”55 In William Shakespeare’s comedy A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the sprite Puck turns the head of Nick Bottom, the play’s hapless lover, into that of a donkey. Bottom, in fact, is such a dolt that he does not even realize his transmutation. A well-read man, Kruse would probably have been familiar with Shakespeare’s use of the ass motif through its original source but, if not, A Midsummer Night’s Dream was made into a successful film starring James Cagney (Bottom), Mickey Rourke (Puck), and Olivia de Havilland (Hermia) just one year before the self-portrait was painted. Several artists have made renditions of the hilarious moment in Shakespeare’s play when the fairy queen Titania fawns over the oblivious donkey-eared Bottom. Henry Fuseli painted Titania and Bottom (c. 1790; Tate Gallery), depicting Titania’s servants waiting on Bottom at their queen’s behest, and Titania, Bottom and the Fairies (1793–94) with an enamored Titania caressing her lover’s altered head (fig. 18).

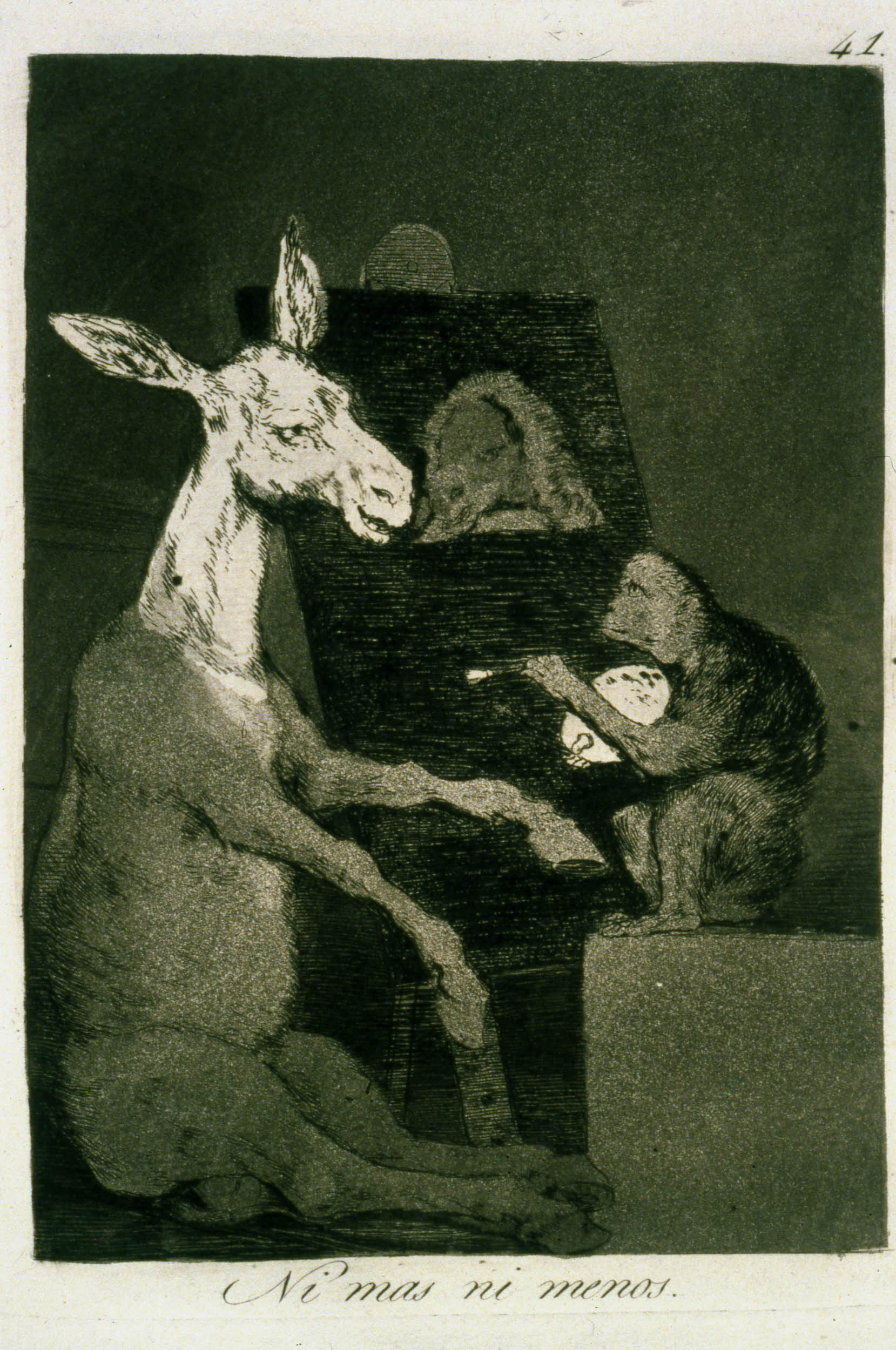

At nearly the same time Fuseli painted his Shakespearean canvases, Francisco Goya conceived Los Caprichos (1797–99), a portfolio of eighty derisive etchings and aquatints that used animal metaphors as a means of social satire. In his far-reaching critiques of Spanish culture, Goya used an anthropomorphized donkey to stand for the aristocracy and monkeys to signify artists and musicians. As a court painter, Goya felt like a trained monkey performing for the jackasses, as seen especially in plate forty-one, Neither More nor Less (Ni más ni menos) (fig. 19), which sharply comments on power relationships and roles within the art world. Kruse himself used an animal metaphor in much the same way in his satirical anti-fascist painting Two Generations (1936), also shown at the Findlay retrospective, where he transforms Kaiser Wilhelm into a kangaroo wearing a traditional German pickelhaube, with a tiny Hitler, replete with farcical ears incised with swastikas, peering out from the emperor’s pouch (fig. 20). This large canvas hung at An Exhibition in Defense of World Democracy: Dedicated to the Peoples of Spain and China, mounted by the American Artists’ Congress and opening in December 1937, alongside work by Gropper, Philip Guston, and Weber, among others. Time magazine singled out Two Generations as a favorite with union members.56

The ass as a sign of stupidity famously finds a place in children’s literature. Pinocchio, the story of the little wooden puppet who wanted to become a real boy, was a staple long before Walt Disney’s 1940 film of the same name. First published in Italian in 1883 and translated into English by 1904, the story includes an episode in which Pinocchio wakes up one morning to find that during the night his ears have grown over ten inches. Hearing Pinocchio’s shrieks of despair, a dormouse visits the marionette’s room and tells him: “Fate has decreed that all lazy boys who come to hate books and schools and teachers and spend all their days with toys and games must sooner or later turn into donkeys.”57 To cut a long story short, the symbol of the ass has historically denoted faulty choices and ideas, much like those of art critics in the 1930s whose tastes were turning toward modernism.

By outfitting himself with donkey ears, long established as a sign of stupidity in art and literature, Kruse mocks his very profession. As an arbiter of taste he sees himself as a hero, but as the subject of such evaluations he found most art critics to be lacking in judgment. With donkey ears, Kruse degrades his critic-self (an ass), which in turn exalts his artist-self, thereby turning the tables on the art critic to vindicate the artist. And here is where the caricature fails. In trying to incorporate his double-barreled perspective on the art critic, with which he clearly grappled, Kruse created an unreadable caricature. Kruse incorporated the ears as a means of ridiculing the profession of art criticism—which included those critics who ignored his work and dismissed realism in general—because of his firm belief in the power of caricature to make an influential statement. As Kruse articulated in a public lecture, “The Art Adventure,” which adopts superhero nomenclature in line with his position in Self-Portrait of an Art Critic: “Cartoonists and caricaturists combating the evils of their eras, have often wielded powerful public influence.” Kruse felt that caricature possessed, he continued, the power to “stir up public indignation [and] . . . to cause the downfall of the . . . corrupt.”58 For Kruse, promoters of the avant-garde were corrupt and unfit to render judgment. His caricature, in part, aimed to skewer those so-called charlatans and faddists in what he hoped would serve as a public visual statement to accompany his copious written statements on the foolishness of art critics. The layers of meaning in Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, however, may also have contributed to the fate of the painting. For even though Kruse capitalizes on his audience’s familiarity with caricature, the self-portrait’s challenging iconography—as opposed to his less abstruse written caricatures—leaves the intricacies of his lampoon falling flat.

The Fate of Self-Portrait of an Art Critic

As much as Kruse disdained the artistic climate in which he lived, he still sought the approval of his modernist contemporaries. Sometime in the winter of 1943 or early 1944, Kruse took Self-Portrait of an Art Critic and at least one other work to the avant-garde Société Anonyme for consideration for their collection. Soon after his visit, Kruse received a letter from Katherine S. Dreier, president of the organization, and Marcel Duchamp, secretary for the group, indicating their disinterest:

Marcel Duchamp and I are terribly sorry that we cannot add your amusing painting ‘The Self Portrait of An Art Critic’ to our Collection of the Société Anonyme. You will have noticed my hesitancy the day you brought your painting, and how I said that the painting of the portrait would be the only one which we might consider, because of its humour. But though both pictures are good, they do not come within the definite direction which this Collection has always followed.59

It is odd that Kruse chose to submit his work to Dreier for consideration, as “the definite direction” of art to which Dreier refers favors the fads Kruse denounced in his art criticism. Among the work the Société Anonyme collected was that of Duchamp, Man Ray, Wassily Kandinsky, and Piet Mondrian.

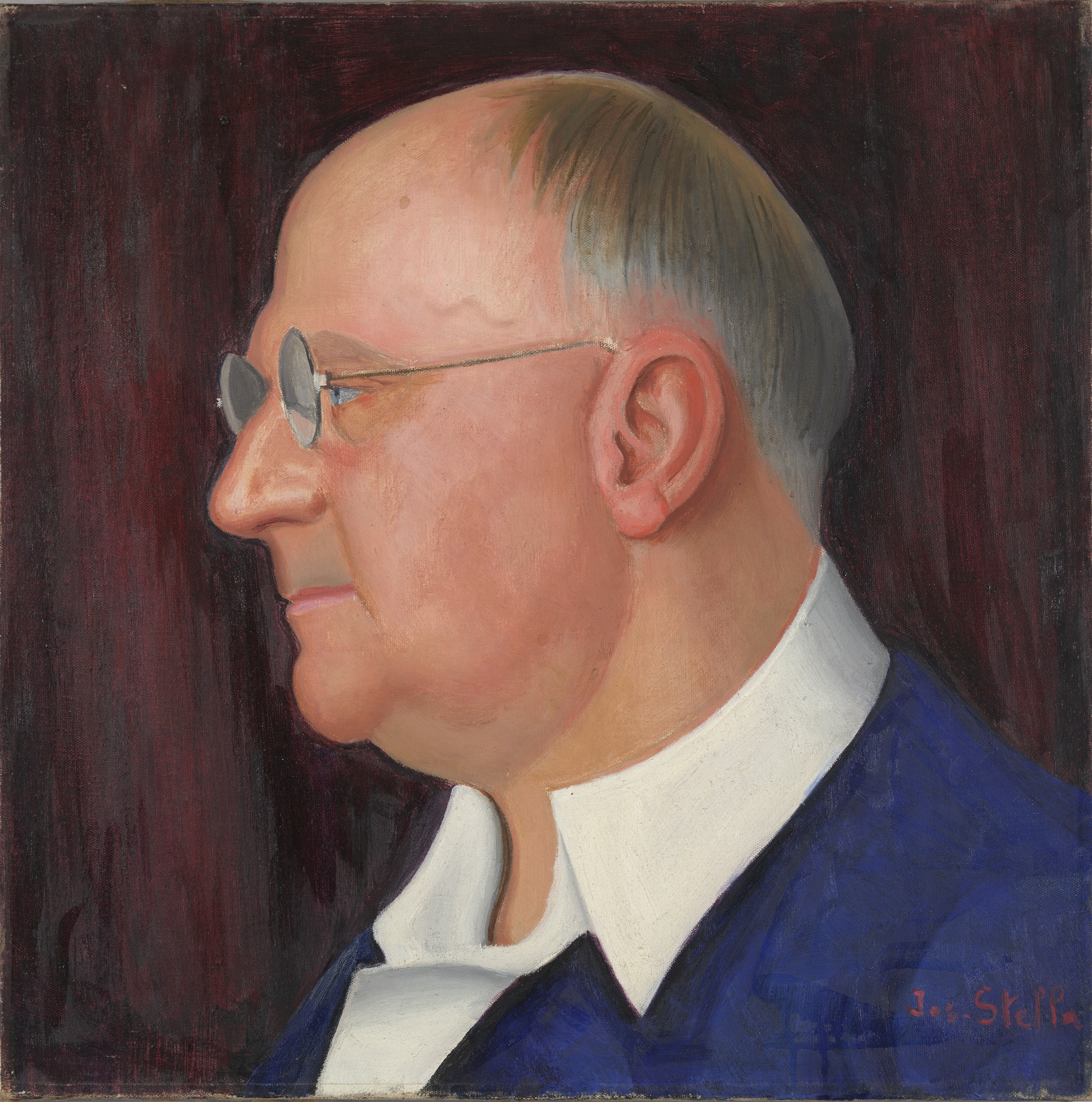

Founded in early 1920 by Duchamp, Dreier, and Man Ray, the Société Anonyme aspired to establish America’s first modern art museum and initiate informed discourse on modern art. The Société Anonyme hosted the first public symposium on Dada in America in April 1921, coming to the consensus that humor, irreverence, irony, and wit defined Dada. These are all qualities found in Kruse’s Self-Portrait of an Art Critic and his art criticism, and are mainstays of caricature in general. At the symposium, Joseph Stella described Dada as “having a good time . . . But it is a movement that does away with everything that has always been taken seriously. To poke fun at, to break down, to laugh at, that is Dadaism.”60 That wit, that poking fun, that subversion of seriousness (certainly mocking the seriousness of the art critic) are features of Kruse’s visual and written work. Take Kruse’s commentary from Art Digest on Stella’s contribution to a 1935 group exhibition. After describing Stella’s work as “refined, perfected and developed,” Kruse continues: “Joseph Stella made his dreams come true by way of powerful lyrics in color . . . his works sparkle with depth of vision, expressed through inspiring pattern placement . . . [He’s] a superior craftsman.”61 In an earlier column from the Brooklyn Eagle, Kruse described Stella as “possibly the most electrifying painter in America today.”62 Notwithstanding Kruse’s bad pun (Stella was known for painting the lights of New York), this accolade for a cutting-edge artist was unusual for the artist-critic. Stella was so appreciative of Kruse’s support that in 1941 he made an oil portrait of him, which unsurprisingly looks nothing like the creature in Self Portrait of an Art Critic (fig. 21). Set against a neutral brown background with only hints of red, Kruse wears conservative attire, as he does in the 1936 self-portrait, but here his clothes cohere with his normative presentation. Stella’s more conventional portrait presents the round-faced, bespectacled Kruse in profile, his human ear nearly front and center and realistically drawn, and his balding head devoid of any animal accoutrements.

In his self-portrait, Kruse also does away with that which has “been taken seriously”—the art critic, himself included. Considered closely, one sees that Self-Portrait of an Art Critic engages the characteristics of Dada valued by Dreier and her colleagues—wit and irreverence, among others—yet presented in a different form than Duchamp and Dove. Dadaists were fond of this kind of punning as well as irreverent acts in art, like Dove’s The Critic, which in its own way is a form of caricature. The irrepressible and publicity-conscious Kruse may have showed his work to the Société Anonyme, an organization that would most likely be antipathetic to his conservative painting style, on the off chance that the art world’s hot ticket might read the painting as an act of Dada and acquire it under that rubric. The direction of the Société Anonyme, however, was emphatically avant-garde, and so nearly a decade later Self-Portrait of an Art Critic still remained in Kruse’s possession.

At the suggestion of an unnamed friend, Kruse offered Howard University six paintings, one of which was Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, in addition to canvases by five other artists, including Lena Gurr, the artist who wrote to the Brooklyn Eagle praising our intrepid artist-critic.63 A letter of December 31, 1952, indicates acceptance of the gift, followed by a letter of March 5, 1953, from a Howard University curator thanking Kruse for the six paintings, which were to be named the Lena Kruse Memorial Collection in honor of Kruse’s mother.64 No further correspondence exists about this donation, and in February 1964, Self-Portrait of an Art Critic appeared on the cover of a catalogue for a solo exhibition of Kruse’s work, where the painting is still listed as part of the Howard University Art Collection.65 In 1998, however, the painting was donated by Kathreen Kruse, in memory of Martin Alexander Kruse (Alexander Kruse’s grandson), to the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami Beach.66 How and why this painting returned to the Kruse family warrants further research and remains an open question.

As amusing as one may find Kruse’s painting before knowing its background, the discordant elements of the self-portrait, which cannot be sorted out without reference to the artist’s writings, could very well relegate the work to a silly little painting by an eccentric artist-critic. Caricature’s success relies on the public recognizing an artist’s referents, much as the comprehension of a joke depends on the identification of cultural signifiers. That is to say, if a reader of Kruse’s art criticism does not know that Gertrude Stein penned “a rose is a rose,” or for that matter does not know Stein’s identity, then the wordplay of Kruse’s commentary would go unrecognized. Kruse’s abstruse painting does not allow easy identification, or to put the matter another way, the canvas is not easily decoded without his art criticism, “the script.” Devree, Duchamp, and Dreier found the work amusing, but that may be due to the incongruity of Kruse showing himself with horns, a mask, and oversized ears rather than because they read the complex meanings embedded in his caricature. On close examination, the anti-modernist Kruse jokingly used oil and tempera to simultaneously validate and condemn the art critic by painting his contradictory views in one of the few dominant artistic fashions of his time, caricature, an artistic mode that necessarily hinges on recognition—in other words— representation. Moreover, Kruse’s modus operandi as a popularizer of art, and his desire to get his body of work as both a critic and an artist known to a mass audience, pushes against the recondite tendencies of modernists such as Duchamp. Kruse’s efforts were an attempt to militate against art that he believed was obscure and elitist, therefore appealing to a small audience. To this point the impact of the discordant caricature, so in need of pairing with its concomitant written commentary, has been lost. Indeed, only when reuniting Kruse’s performances in paint and on paper can one come to a richer understanding of the artist, his self-portrait, and contested positions of modernism and representation in the 1930s.

Cite this article: Samantha Baskind, “Of Masks, Mockery, and Modernism: Alexander Z. Kruse’s Self-Portrait of an Art Critic,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2023.

PDF: Baskind, Of Masks, Mockery, and Modernism

Notes

The author would like to thank Brad Collins, Erika Doss, and Ellen Landau for their invaluable advice on earlier iterations of this manuscript.

- The Wolfsonian-FIU curatorial files in Miami Beach, Florida, date the painting “before 1941,” but my research more precisely indicates that the painting was made in 1936. Kruse includes the painting, with a date, in a list he wrote of the works in his April 22 to May 10, 1941, retrospective at Wally Findlay Galleries in New York. See Alexander Kruse Papers, 1888–1972, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, roll 1460, frame 607 (hereafter Kruse papers). The catalogue for the exhibition also has the painting dated as 1936 (roll 1460, frame 760). ↵

- Benedict Kruse, Taking Art to Heart: The Life and Times of A. Z. Kruse (Salt Lake City: Northwest Publishing, 1994), 116. The only full-length book on Kruse, this monograph is valuable but flawed. Written by his son, the book sometimes veers into sentiment. ↵

- Kruse papers, roll 1461, frame 241. ↵

- “A Mayor’s Portrait,” Art Digest 10 (February 31, 1936): 28. ↵

- For a letter about the proposed show, see Kruse papers, roll 1460, frame 284. For a script, see roll 1460, frame 286. For other matters related to the project, see frames 287–95. Column proposal in frames 311 and 314. ↵

- Boston Sunset (1926; collection unknown) portrays the Italian immigrant anarchists hung on a cross, a more stringent conception than the later and better-known canvases addressing the biased case by Ben Shahn, which are named The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti rather than actually showing “the Passion.” The Modern Monthly, a leftist periodical, reproduced Boston Sunset on its cover with a small caption explaining that the painting was barred from the John Reed Club because it contained crosses and was refused space in all galleries save one (unnamed), which only allowed private viewings. Studio News reproduced Boston Sunset in the interior and at over half a page with a similar caption, also adding that the canvas was now owned by the Rand School of Social Science, an institution associated with the Socialist Party. The Modern Monthly 7, no. 7 (August 1933) and Studio News 5, no. 1 (December 1933): 5. ↵

- Cécile Whiting, Antifascism in American Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), esp. 98–99. ↵

- As of the November 15, 1936, column, the name of the feature changed to “Art Talks.” On January 15, 1939, the column title is once again “Art to Heart Talks.” ↵

- Wambly Bald, “Art Soothes the Nerves and Salts the Ego,” New York Post (Home News Magazine) (June 24, 1949), 1. ↵

- William Murrell, A History of American Graphic Humor, vol. 1 (1747–1865) (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1933), 5. ↵

- E. H. Gombrich and E. Kris, Caricature (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1940), 13. ↵

- Wendy Rick Reaves elaborates on this point in her excellent exhibition catalogue, from which I have drawn material for this article. See Celebrity Caricature in America (Washington, DC: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, 1998), especially 13–14, 18, and 88. ↵

- Alexander Kruse as quoted in Benedict Kruse, Taking Art to Heart, 6, 7. ↵

- Kruse papers, roll 1459, frame 83. Capitalization in the original. ↵

- The caricature’s accompanying caption reads: “In case you’ve never seen an art critic this is how they look—at least to caricaturist Al Hirschfeld who peeked when they gathered together in a basement restaurant and dubbed themselves ‘The Art Critics Circle.’ From left to right around the horrendous horseshoe, they are Betty Chamberlain of Time; Aimée Crone of Stage; Peyton Boswell, editor of Art Digest; Emily Genauer of The World Telegram; Edward Alden Jewell and Howard Devree of The Times; Carlyle Burrows of The Herald Tribune; Maude Riley of CUE; A. Z. Kruse of The Brooklyn Eagle; Nelson Lansdale of Newsweek; Rosamund Frost of Art News; Elizabeth McCausland of The Springfield Republican; and Frank Caspers of Art Digest.” ↵

- Kruse papers, roll 1460, frame 1471. ↵

- Helen Boswell, “Fifty-Seventh Street in Review: Alex Kruse of the ‘Eagle,’” Art Digest 15, no. 15 (May 1, 1941): 20–21. ↵

- A. Z. Kruse, “Art to Heart Talks,” Art Digest 9, no. 19 (August 1, 1935): 24. An August 1, 1969 clipping from the Christian Science Monitor in Kruse’s personal papers, annotated in his handwriting “caption for cartoon,” states, “Young man, it takes a lot more to make a great modern artist than only an almost total lack of technical ability.” Kruse papers, roll 1459, frame 1786. ↵

- A. Z. Kruse, “Art to Heart Talks,” Art Digest 9, no. 20 (September 1, 1935): 19. ↵

- A. Z. Kruse, How to Draw and Paint (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1953), vii. ↵

- A. Z. Kruse, How to Draw and Paint (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1953), vii. ↵

- A. Z. Kruse, “Art to Heart Talks,” Art Digest 9, no. 4 (November 15, 1934): 4. ↵

- Kruse, “Art to Heart Talks,” Art Digest 9, no. 4 (November 15, 1934): 4. In the 1950s, with the ascension of Abstract Expressionism, a number of artists adamant about representational art began the journal Reality: A Journal of Artists’ Opinions. Published annually for three years (1953–55), the journal had the support of many well-known artists, including Edward Hopper, Jack Levine, and Reginald Marsh. Levine wrote an article that employs aggressive humor to convey a sense of some artists’ frustration vis-à-vis Abstract Expressionism: “We have no respite from puerile self-utterances in recent painting exhibitions, all rendered in the abstract, a Rorschach of neuroses, epilepsies, compulsive fetichisms {sic} and what not. It’s less interesting than might be the psychoanalytical case history of an Easter Bunny.” Jack Levine, “Man is the Center,” Reality 1, no. 1 (Spring 1953): 5. ↵

- A. Z. Kruse, “How Luks Explained It,” Art Digest 8, no. 14 (April 15, 1934): 7. The early columns were yet to be titled “Art to Heart Talks.” ↵

- Theodore Roosevelt, “A Layman’s Views of an Art Exhibition,” Outlook 103 (March 29, 1913): 719. ↵

- Bettijune Kruse, the artist’s daughter-in-law, told me about Kruse’s admiration for and interest in the Algonquin Round Table. Bettijune Kruse to the author, May 9, 2010. ↵

- The Art Critics Circle, by name and intent, was clearly trying to reconstruct the kind of camaraderie, and perhaps the notoriety, of the Algonquin Round Table. ↵

- Robert Benchley, My Ten Years in a Quandary, and How They Grew (New York: Harper Brothers, 1936), 56. ↵

- As quoted in Margaret Case Harriman, The Vicious Circle: The Story of the Algonquin Round Table, illustrated by Al Hirschfeld (New York: Rinehart, 1951), 16. Harriman was the daughter of the owner of the Algonquin Hotel. For an anthology of the work of the Algonquin writers, see The Algonquin Wits (New York: Citadel, 1968). ↵

- Edna Ferber, A Peculiar Treasure (New York: Garden City Publishing, 1940), 292–93. ↵

- Margaret McFadden, “‘Warning—Do not risk federal arrest by looking glum!’: Ballyhoo Magazine and the Cultural Politics of Early 1930s Humor,” Journal of American Culture 26, no. 1 (March 2003): 124. ↵

- D. B. Wyndham Lewis and Charles Lee, eds., The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse (London: J. M. Dent, 1930). ↵

- Martha Bensley Bruère and Mary Ritter Beard, Laughing Their Way: Women’s Humor in America (New York: Macmillan, 1934). ↵

- Constance Rourke, American Humor: A Study of the National Character (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1931); Walter Blair, Native American Humor (1800–1900) (New York: American Book Company, 1937). ↵

- On radio humor during the Great Depression, see Arthur Frank Wertheim, “Relieving Social Tensions: Radio Comedy and the Great Depression,” Journal of Popular Culture 10, no. 3 (Winter 1976): 501–19. A special issue of Studies in American Humor (2015) looks at humor across media in the 1920s and 1930s, including cartoons, film, and radio. See especially Margaret T. McFadden’s essay about Kruse’s childhood friend Eddie Cantor: “‘Yoo-Hoo, Prosperity’: Eddie Cantor and the Great Depression, 1929–36,” Studies in American Humor 1, no. 2 (2015): 255–78. ↵

- For an excellent discussion of humor in the downtrodden 1930s in conjunction with Grant Wood’s art, see Erika Doss, “Grant Wood’s Queer Parody: American Humor during the Great Depression,” Winterthur Portfolio 52, no. 1 (Spring 2018): 3–45. Although preceding Kruse’s time, Jennifer Greenhill, Playing it Straight: Art and Humor in the Gilded Age (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012) convincingly demonstrates the importance of humor in late nineteenth-century American art and culture. ↵

- See Roland Marchand’s discussion of the “color explosion” in advertising in Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920–1940 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 120–37. ↵

- Reaves, Celebrity Caricature in America, 211–13, 271. ↵

- John Wilmerding examines American artists who place their signatures within the narrative of paintings in Signs of the Artist: Signatures and Self-Expression in American Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003). He argues that by conspicuously signing a painting the artist may be making a larger statement related to his or her association with the work’s subject rather than simply taking responsibility for the image’s production. ↵

- A. Z. Kruse, “Art to Heart Talks,” Art Digest 9, no. 10 (February 15, 1935): 22. ↵

- Royal Cortissoz, Personalities in Art (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), 8. ↵

- See Robert Francis, “Practices What He Preaches—Eagle Critic Has Own Show,” Brooklyn Eagle (April 22, 1941), 4; Emily Genauer, “Solo Exhibitions by Two Brave Art Critics,” New York World Telegram (April 28, 1941), Kruse papers, roll 1460, frame 1471. ↵

- See clipping in Kruse papers, roll 1460, frame 1471. ↵

- Kruse papers, roll 1460, frame 759. ↵

- Royal Cortissoz quoted in “Royal Cortissoz, Art Critic, 79, Dies,” New York Times (October 18, 1948), 23. ↵

- Kruse papers, roll 1459, frame 1112. Emphasis in original. ↵

- The most recent exhibitions of Kruse’s work were held at the Educational Alliance in New York City (2003) and the Huntington Library and Art Gallery in San Marino, California (1997). On the latter see Carrie Haslett’s small but excellent catalogue From Pushcarts to Paradise: The New York of Alexander Z. Kruse (1888–1972) (San Marino: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, 1997). In 1966, New York’s Burrell Galleries mounted a retrospective, “Alexander Z. Kruse: 50 Years in American Art.” The fourteen-page catalogue includes laudatory quotes from a number of important figures, such as Bernard Berenson: “It is a rare pleasure to find painting as inspired and disciplined,” in Alexander Z. Kruse: 50 Years in American Art (New York: Burrell Galleries, 1966), unpaginated. ↵

- Guy Pène du Bois, Artists Say the Silliest Things (New York: American Artists Group, 1940), 160, 161. Of his art criticism, Pène du Bois thoughtfully reflected in a way that Kruse never did: “It seems to me that the only test I applied to an artist was merely whether he was or was not a realist,” 161. ↵

- Kruse papers, roll 1459, frame 1034. ↵

- Sigmund Freud, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, trans. and ed. James Strachey (1905; reprint, New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1960), 97 (emphasis original). ↵

- Gershom Legman, Rationale of the Dirty Joke: An Analysis of Sexual Humor (New York: Grove Press, 1968), 9. ↵

- Edward Alden Jewell, “American Art on View,” New York Times (January 4, 1932), 26. ↵

- Stanley Burnshaw, André Spire and His Poetry (Philadelphia: The Centaur Press, 1933). ↵

- Frank A. Nankivell, “The Work of Alexander Kruse,” Prints 5, no. 3 (March 1935): 32. Although it was published two years after Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, it is worth pointing out that a short book, Two New Yorkers, paired fifteen works of art by Kruse in concert with poetry by Alfred Kreymborg. See Alexander Z. Kruse and Alfred Kreymborg, Two New Yorkers (New York: Bruce Humphries, 1938). The book was reprinted three years later under the title A Marriage of True Minds (New York: Dryden Press, 1941). ↵

- Desiderius Erasmus, The Praise of Folly, trans. Clarence H. Miller (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 13. Kruse’s copy of The Praise of Folly is housed as part of the Kruse papers, Huntington. ↵

- “Art: Congress,” Time 30, no. 26 (December 27, 1937): 36. ↵

- Carlo Collodi, Pinocchio (1883; reprint, London: Sovereign, 2013), 103. ↵

- Kruse papers, reel 1460, frame 265. ↵

- Katherine Dreier and Marcel Duchamp to Alexander Kruse, January 19, 1944. Kruse papers, roll 1459, frame 991. ↵

- Joseph Stella quoted in Rudolf E. Kuenzli, ed., New York Dada (New York: Willis Locker and Owens, 1986), 140. ↵

- A. Z. Kruse, “Art to Heart Talks,” Art Digest 9 (January 15, 1935): 8, 24. ↵

- Alexander Kruse quoted in Benedict Kruse, Taking Art to Heart, 99. ↵

- For correspondence on the donation, see Kruse papers, roll 1459, frames 1178 and 1459, 1181, 1461, and 281. No documentation exists as to the identity of the friend who suggested the donation to Howard, but most likely the gift was fueled by Kruse’s enthusiasm that his art would be in a new museum rather than a strong inclination to offer objectified cultural capital to a historically black college. By no means am I indicating that Kruse was unsympathetic to the struggles of African Americans. Collection building at historically black colleges played a role in donations for others, including Georgia O’Keeffe’s major gift to Fisk University in 1949, but Kruse’s foremost concern was promoting his career and artistic legacy. ↵

- Kruse papers, roll 1459, 1184. Two accession numbers, 52.82 and 52.6, are on the back of the painting. ↵

- Kruse papers, roll 1460, frame 837. ↵

- Wolfsonian-FIU curatorial files. ↵

About the Author(s): Samantha Baskind is Professor of Art History at Cleveland State University