Sally Webster

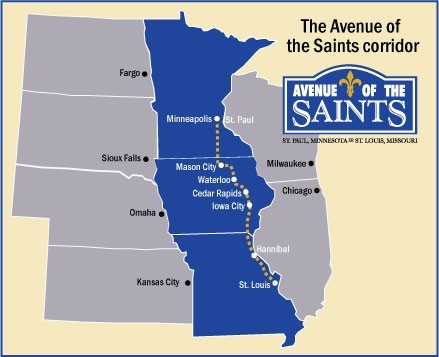

Last May, my husband and I flew to St. Louis to attend our granddaughter’s graduation from Grinnell College in Iowa, reputed to be the most liberal campus in America. Our drive northward was along the Avenue of the Saints (fig. 1), a name that conjured a pilgrimage route in northern Spain. Was this America’s Camino de Santiago de Compostela? No such luck; instead of grottos and shrines, there were discreet signs for beer, and admonitions to “Choose Life” and “Support Our Troops.” My son, who was driving, brought me back to earth by explaining that the Avenue of the Saints was a modern, four-lane parkway linking three states—Missouri, Iowa, and Minnesota—a pilgrimage route established for businesspeople who travel between St. Louis and St. Paul.

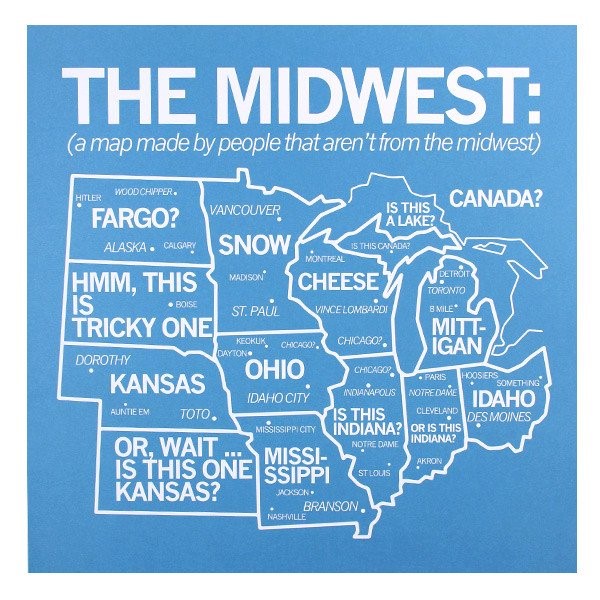

This Midwest—St. Paul, St. Louis, and Chicago—is familiar to me. It is where both my adult children live. Our son and his family lived first in St. Paul and now in St. Louis; our daughter and her wife are in Chicago. And I, an ardent New Yorker, was born in Indiana. These have never been flyover states for me, but their newfound political power came as a shock. The Midwest: (a map made by people that aren’t from the Midwest) (fig. 2), humorously visualizes the preconceptions and unfamiliarity of bicoastal snobs with that part of the country that by and large supported and continues to endorse President Donald Trump. How have we liberal academics become so disconnected from our country’s interior?

Hoping for enlightenment, I looked out the car window for answers and found a prosperous countryside north of St. Louis. Malls, office parks, and healthcare centers dot the landscape. Further along and into Iowa, this exurbant scenery gave way to untold acres of rich farmland that in late May held the green sprouts of late summer corn. This was not the rundown, post-industrial landscape of West Virginia or Kentucky that we see on the nightly news. Along with a gun store sign that read “Protect our Heritage,” there was a notice to “Go Solar,” and directions to “The Aviary, a Recovering Community” in Eolia, Missouri. Once in Iowa, we passed a fireworks superstore, the Riverside Casino, and Godfather’s Pizza at Exit 80. At the intersection of Route 92 and US 218N were the towns of Washington and Columbus Junction, names that document a story of migration and settlement. What ambitions or hubris prompted a community to call itself Bonaparte, Montezuma, Palmyra, Canton, or Memphis? Further north, and adding to the pastoral incongruity, were signposts for both the Iowa National Guard Readiness Center and the Amana Colonies, a utopian community founded in the mid-nineteenth century by German Pietists. Finally, just east of Grinnell in a field where black Angus grazed, was a large Adult Superstore. The bucolic scenery of Iowa laid bare a land of contradictions.

What I found captured my imagination but was not revelatory; the landscape, while revealing paradoxes, was mute. Before my trip and since Trump’s inauguration, I have talked with people—friends, family—about what they have heard, observed, and experienced from Trump supporters. Their reports are frightening—the hatred Trump adherents feel toward liberals is profound. This divisiveness concerns me. I am less bothered by Trump’s pronouncements than I am by my inability to find intellectual common ground with his supporters or to plumb the reasons for his appeal. At the same time, I believe that Trump creates a smokescreen, distracting and blinding us to a more sinister reality, which is in fact our disengagement from one another. How do we find our way back to tolerance—to listening, to respect?

Surprisingly perhaps, the word patriotism bubbled up. I recalled two recent conversations that I had had on the subject: one with a colleague and one with my St. Louis daughter-in-law. The colleague asked me what methodology informed my work, which I presumed was a reference to my last book on the nation’s first monument. I shot back, “patriotism,” and was met with a dead silence. I knew that patriotism was not a methodology and was uncertain why I conjured that word. This conundrum would not go away, and during my visit to St. Louis, I asked my daughter-in-law, “do you love your country?” There was a shocked silence, “Of course I love my country.” Her shock implying why I was even asking the question. My daughter-in-law, who works for the Federal Reserve, is a patriotic American. It was time to admit that I was too. She and I are both aware of the negative connotations of the word and its exploitation by dictators such as Adolf Hitler or American politicians such as Senator Joseph McCarthy. Our patriotism is more in line with the definitions set out by the philosopher Steven Nathanson in his 1993 book, Patriotism, Morality, and Peace. In it, he defined patriotism as a “special affection for one’s own country,” a “sense of personal identification with the country,” a “special concern for the well-being of the country,” and a “willingness to sacrifice to promote the country’s good.”1

I had already stuck my toe in the waters of patriotism with my book The Nation’s First Monument and the Origins of the American Memorial Tradition (2015). In retrospect, I wish I had tackled love of country head on. Now I want to better understand what motivated me to write about the nation’s first monument. Initially I had thought that this study would help me better understand our nation’s memorial tradition. There are few models for this type of work, and I chose to follow a traditional, academic one of tracing influences from the past and connecting the General Richard Montgomery Memorial, 1777, to later monuments. This enabled me to tease out the idea that the monument expressed a moment in time when glimmerings of independence meshed with a desire to retain a connection to European civilization. Yet after it was published, I felt that—despite all the heavy documentation I had assembled in support of my argument—there was a hole in the middle. Missing was my failure to claim that this monument, a memorial to Montgomery commissioned by Benjamin Franklin on behalf of the Continental Congress and designed by a Frenchman, was the nation’s first patriotic tribute to a brave hero who gave his life for the cause of liberty. What I had not acknowledged was that the Montgomery monument, along with the American flag and the Great Seal, were the first patriotic symbols of a new nation. Historically, I am justified in making this claim since at this turning point in our national narrative, patriotism was a supreme and all-embracing virtue, and I ask myself now, is it less so today?

Isn’t it patriotic that we care passionately about what the new federal administration is doing to our country? Aren’t our protests, letter writing, and community organizing confirmation of our patriotism? Aren’t we beginning to see with new eyes the fragility of our national compact? Is there more that we as academics can do to help take us back, not to a golden age, but to a common concern for our country and its welfare? If so, how would we accomplish this? Can it be manifested in our writing and lecturing? Can it be done without sounding the clarion calls of nationalism or exceptionalism? Is it worth doing? Does and should civic pride enter our discourse?

With these thoughts in mind, I reflected on my past teaching and realized that without calling it such, I worked from the premise of love of country. To take just one example: several years ago, I decided to create a counter-narrative for my graduate students, a reconceptualization of the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition. While not ignoring the scholarship around racism and exclusionism established by writers such as Robert Rydell, I focused instead on the positive impact the fair had on the Midwest—on the planning of its burgeoning cities; the design and decoration of its new state capitols; its influence on the creation and establishment of now-lauded cultural and educational institutions; the establishment of the Midwest as an important region economically; and its integral role in linking the east and west coasts. For me, the rethinking of the World’s Columbian Exposition was a way to create interdisciplinary dialogues among students of visual culture, urban planning, architecture and landscape history, commemorative sculpture, and mural painting, all of which we discussed and analyzed within a national context. The result was an expanded understanding of the Exposition that acknowledged the tectonic shift that occurred in the middle of the country at the turn of the century.

These ponderings were on my mind as we left the Avenue of the Saints in Iowa City, a city associated with Grant Wood and the Regionalists, and found ourselves smack dab in the middle of cornfields that stretched to the horizon in every direction. We reached Grinnell about suppertime, having stopped off at Swedesburg. Here an outsized, painted wooden horse graced the entrance to its tiny Swedish Heritage Museum, reminding me that Iowa, like the rest of the United States, was settled by immigrants, in this case New Englanders, Germans, and Swedes. We were joined at our destination by family members, and together we enjoyed the simple pleasures of a festive occasion. When the trip was over, I left Iowa with an aching concern for our great nation, asking myself what historians of American art can do to help. How can we work to reclaim love of country? Finding ways is our patriotic duty.

Cite this article: Sally Webster, “Bully Pulpit,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 3, no. 2 (Fall 2017), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1616.

Notes

- Stephen Nathanson, Patriotism, Morality, and Peace (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 1993), 34–35. ↵

About the Author(s): Sally Webster is Professor Emerita at the City University of New York.