We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85

Curated by: Catherine Morris and Rujeko Hockley

Exhibition schedule: Brooklyn Museum, April 21–September 17, 2017; California African American Museum, Los Angeles, October 13, 2017–January 14, 2018; Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, February 17–May 27, 2018; and The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, June 26–September 30, 2018

Related Publication: Catherine Morris and Rujeko Hockley, eds. We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 / A Sourcebook. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum, 2017. 320 pp.; 40 illus. Softcover $24.95 (ISBN: 9780872731837 0872731839)

The Brooklyn Museum exhibition, We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85, showcases art by nearly forty black women, as well as some Latina and Asian women and black men from the period noted. The resulting mosaic of perspectives dares us to rethink the very idea of revolutionary practice—artistic and otherwise, then and now, and includes work that runs the gamut from painting, photography, prints, assemblage, and sculpture to film, video, and performance art. In framing this eclectic collection, curators Catherine Morris of the Brooklyn Museum and Rujeko Hockley of the Whitney Museum of American Art supply an interpretive context rooted in the particular circumstances of black women amid liberation struggles in the United States from 1965 through 1985. In doing so, Morris and Hockley forgo a concentration on canonical art-historical movements when the presence of this canon might subsume specificities of the featured work, specificities understudied for far too long. Above all, the curators aim to reformulate and refine established chronicles of this time period, as they pertain to American art, feminism, and political change, by presenting salient artwork central to the makers’ challenges to the narrow understandings of class, gender, race, and sexuality that ensured their oppression. In effect, We Wanted a Revolution intimates that black women could not develop an art practice without also developing “a place for their own voices to be heard and their own work to be made and received,” because numerous forces of oppression (whether anti-blackness in the Women’s Movement, sexism in the Black Power Movement, or both in the art world) enveloped and prohibited them.1 While promoting the realization of such a place at the Brooklyn Museum, this exhibition addresses how the artwork acted as an agent of change in the communities where it initially circulated.

Moreover, this exhibition stands out for the ways it counters the curatorial tendency to elide or abstract the complex and pragmatic inter- and intra-community dealings behind the art it mounts. Steering clear of a simplistic or grand narrative, We Wanted a Revolution accentuates how its artists harnessed these dealings to bolster the revolutionary content of their work. As a result, visitors have the opportunity to explore an array of prescient tactics for collective struggle and conscientious art-making and to examine the inevitable perils of these activities.

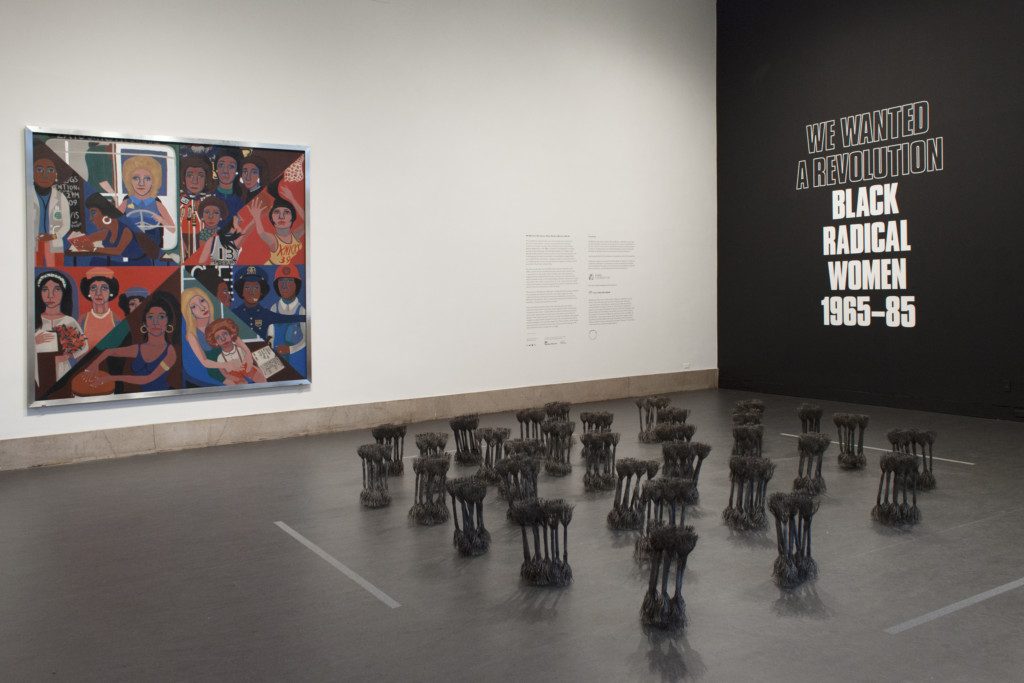

From the outset, We Wanted a Revolution characterizes its artists’ various radical aspirations as grounded in a sense of social accountability. At the entrance, Faith Ringgold’s mural For the Women’s House (1971; collection of Rose M. Singer Center, East Elmhurst, N.Y.) greets visitors with a kaleidoscopic scene of female protagonists of numerous ages and races. The women matter-of-factly perform roles deemed transgressive for their gender at the time the painting was completed. In adjacent vignettes, we see a president, professional league basketball players, and an unwed mother reading quotations from Coretta Scott King and Rosa Parks to her child.2 Ringgold pictured a world where women partake in society on their own terms for viewers whom society did not afford this opportunity: the inmates at the Correctional Institution for Women on Rikers Island. In a published interview, the artist and her daughter, cultural critic Michele Wallace, emphasize that Ringgold gave her incarcerated audience a plausible feminist vision that responded to what the inmates told her they wanted to see.3 Wallace applauds this project as an intriguing alternative to a prevalent rhetoric of resistance incommensurate with peoples’ everyday hardships. She concludes: “The revolution is too abstract, as it has turned out, far more abstract than any of us might have suspected. Therefore, the revolution has been too conveniently removed from our daily actions.”4 As if heeding this observation, We Wanted a Revolution respects the radical merit of artists attuned to life’s practical demands.

If the exhibition strays from aloof political postures, it still encourages visitors to embrace the potency of abstract art. On the floor in front of Ringgold’s painting, Maren Hassinger’s installation Leaning (1980; fig.1) opens the exhibition. Composed of dozens of shrub-like sculptures tilting in multiple directions as if blown by a desert storm, Hassinger’s atomized clusters of wire rope are evocative, not illustrative. Within a shared matrix, the physical differences among her units become all the more apparent. Hassinger’s arrangement, like Ringgold’s figurative painting for a community of imprisoned women, locates individual expression within a collective, concrete site. I propose that, as exemplified by these two inaugural works, the exhibition conveys a distinct, revolutionary ethic in lieu of a consistent revolutionary aesthetic. This ethic acknowledges the interdependency of people, defends personal expression without indulging illusions of complete personal autonomy, and pursues sustainable, empathetic strategies conducive to social inclusivity.

Fittingly, such a revolutionary ethic undercuts the dominant frameworks of resistance that have attended inadequately to the concerns of black American women. In this regard, the ethical orientation of the exhibition undermines the Black Power mantra of “by any means necessary.” Not coincidentally, the textual components of We Wanted a Revolution explicitly and implicitly echo language from the pioneering 1970s black feminist group, the Combahee River Collective, whose manifesto states, “[i]n the practice of our politics we do not believe that the end always justifies the means. Many reactionary and destructive acts have been done in the name of achieving ‘correct’ political goals.”5 Certainly, an ends-justify-the-means stance undergirds second-wave feminists’ penchant for neglecting experiences that differed from their middle-class, white, European American, heterosexual base. As the exhibition’s didactic material underscores, feminist groups frequently perceived the grievances of women of color as obstacles to abolishing patriarchy. The exhibition’s references to such skirmishes on the ground also notably depart from the disembodied, transcendent positions assumed by numerous modern artists who famously aligned themselves with revolution. Instead, We Wanted a Revolution poses the practical means—e.g., the negotiation of artistic processes, social and political institutions and infrastructures, psychological and physical needs, and what Wallace calls “daily actions”—as constitutive of, instead of incidental to, revolutionary ends.

To impart the ways that the art on view broaches these sentiments, thematic wall text, labels, and archival records narrate each gallery section. Scattered throughout, glass cases invite visitors to study sources on political controversies and conversations pertinent to nearby installations. These vitrines are a prominent and popular element of the show. They contain a wealth of primary research, such as news articles from the timespan under review, in addition to brochures, protest flyers, essays, letters, and photographs by and about the artists in the exhibition.

After its entrance, the exhibition unfolds in eight sections, arranged in a loose chronological progression. In keeping with the overarching emphasis on artistic and social interdependency, every section spotlights individual contributors in conjunction with networks and/or political issues that link neighboring art objects. Focusing on the Black Arts Movement, the first full gallery section presents objects geared toward political uses and contemplation, while flagging tensions among participants of this Black Arts milieu. Posters and prints with Afrocentric designs, vibrant colors, and graphics of black American historical heroines stretch across a long wall. The works on paper demonstrate how those associated with this movement employed printmaking to generate work that was monetarily and culturally accessible to black communities. Before this same wall, three-dimensional works accentuate the exquisite ways that black pride assumed embodied, feminine forms. The curvaceous contours of the Elizabeth Catlett cedar sculpture, Homage to My Young Black Sisters (1968; collection of Reginald and Aliya Browne) crescendo in a Black Power salute. Jae Jarrell’s fashion garments also attest to the translation of artists’ revolutionary gestures into the streets. Fabricated with patchwork and appliqué techniques, her radiant dresses Ebony Family (1968; Brooklyn Museum) and Urban Wall Suit (1969; fig. 2) are wearable collages of the imagery described by their titles. Lest viewers doubt their wearability, a black-and-white photograph accompanies them to show Jarrell donning Urban Wall Suit. In this snapshot, the designer sports the armor-like clothing as she stands by an urban fence with her two young children. This image of Jarrell as a mother and artist offers a glimpse into how she used her creative enterprise to reimagine traditional female duties, such as childcare, and embolden black women. Jarrell was a cofounder of the Chicago-based AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) that, along with the New York City-based collectives Spiral and Weusi, backed several artists represented in this section. Wall texts stress that men composed the majority of these black artist groups of the 1960s and early 1970s; Emma Amos was the only woman in Spiral. The secluded appearance of recurring self-portraits of Amos in her oil paintings Flower Sniffer (1966; courtesy of the artist and Ryan Lee Gallery, New York) and Sandy and Her Husband (1973; courtesy of the artist and Ryan Lee Gallery, New York) reflects this gender disparity. Despite the vital support of cultural networks connected to the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, few allotted female members sufficient space.

In contrast to Amos’s portrayal of herself as a slight, huddling observer, most of the compositions in the second section privilege solitary women whose bodies overtake their respective pictorial and physical spaces. These artistic avatars exude self-determination. Furthermore, these figures assume multiple media and situations, whether emerging in the oppressive setting of the Kay Brown etching Sister Alone in a Rented Room (1974; collection of Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York) or in the billowy woolen tendrils of the anthropomorphic sculpture by Barbara Chase-Riboud, Confessions for Myself (1972; fig.3). Here again, we sense the contributors’ ethical imperative against exclusionary art paradigms. The wall text unpacks the national relevance of this imperative by mentioning other barrier-breaking hallmarks of the period, such as the induction of Shirley Chisholm as the first African American woman to join the United States Congress in 1968. In sum, this second portion of the exhibition draws attention to black women’s innovations for artistic and organizational self-representation.

The curators posit such endeavors against and in proximity to second-wave mainstream feminism. A placard with the heading “BLACK FEMINISM” explains that black women in this era developed their own methods for combating sexism according to their own social priorities. Some even opted for the identification of womanist, a term “[c]oined by Alice Walker in 1983—and defined as ‘a black feminist or feminist of color . . . committed to [the] survival and wholeness of entire people, male and female.’” Looking not only to survive but to thrive, Kay Brown, Dindga McCannon, and Faith Ringgold banded together to start their professional confederation, “Where We At” Black Women Artists (WWA), in 1971. Vitrines of texts from WWA events as well as concurrent promotional art and news publications relay how black women rigorously inserted themselves into public discourse.

These archival accounts heighten the contradictions of institutional failures to incorporate long-term platforms for black women. The 1972 article by Kay Brown detailing the brief history of WWA concludes with six demands that members had issued to the Brooklyn Museum at an open hearing. Demand number one was to have “A Black Women’s Exhibition.”6 The Brooklyn Museum delivered with the exhibition under review but only after nearly a half century. When entering this exhibition, it is difficult not to notice yet another elephant in the room—the permanent installation of The Dinner Party (1974–79; Brooklyn Museum) by Judy Chicago. The monumental mise en scène sits at the heart of the museum’s Elizabeth Sackler Center for Feminist Art. The Dinner Party consists of a triangular table bedecked with place settings, each dedicated to a female trailblazer. As exhibition contributor Lorraine O’Grady points out, of the thirty-nine women with a place setting, Sojourner Truth is the sole black guest.7 Today, Truth remains the only black woman with a reserved seat at the actual and proverbial table.

Without remarking on these instances, the curators’ thoughtful redress of such neglect should not be underestimated. Then again, neither should the belatedness of their exhibition. Minimizing the latter consideration in his otherwise sensitive discussion of We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, Holland Cotter opined: “[t]he only change I would make . . . would be to tweak its title: I’d edit it down to its opening phrase and put that in the present tense.”8 However, this suggestion to elide the source of the utterance and the use of the past tense in the title dismisses, or at least misses, the critical implications of the pastness of the artists’ revolutionary assertions. In the exhibition, the historical treatment of the black women’s demands does not make the demands less urgent; it instead urges us not to take the work of fulfilling them for granted. In tandem with its display of art and archival treasures, the wording of the exhibition title makes the case not only for the recognition of the black women’s self-expression, but also the long-reigning and even local negation of this expression.

We Wanted a Revolution revises the historical terrain on which it treads while excavating it with nuance. Instead of sidestepping artists’ conflicts within their communities, the curators delve into these thorny patches. For instance, the third section, broadly organized around the theme of art world activism of the 1970s and 1980s, highlights debates that played out in feminists’ creative collaborations and elsewhere. Here we find trenchant works from Dialectics of Isolation, Ana Mendieta’s 1980 exhibition of Third World women artists at Artist In Residence (A.I.R.). Mendieta’s curatorial intervention confronted A.I.R., the first all-women’s cooperative gallery in the nation, with the First-World biases of its membership. In We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 / A Sourcebook, Catherine Morris introduces the Third World as a “loosely related group of countries emerging from colonial control and struggling with attendant economic disadvantages.” Morris continues, “[a]rtists of color from the Third World were continually denied the visibility, economic stability, and support systems of the Western art world.”9 The exhibition We Wanted a Revolution touches on these mechanisms of colonial disavowal among North American feminists. Published artwork and articles from some of Mendieta’s contributors surface in a constellation of pages from Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics. Although the journal was run by a relatively privileged, white core, the editors occasionally solicited women with other backgrounds for special issues, such as Lesbian Art and Artists, 1977; Third World Women, 1979; and Racism Is the Issue, 1982, which provide a fascinating subtext for the surrounding art.

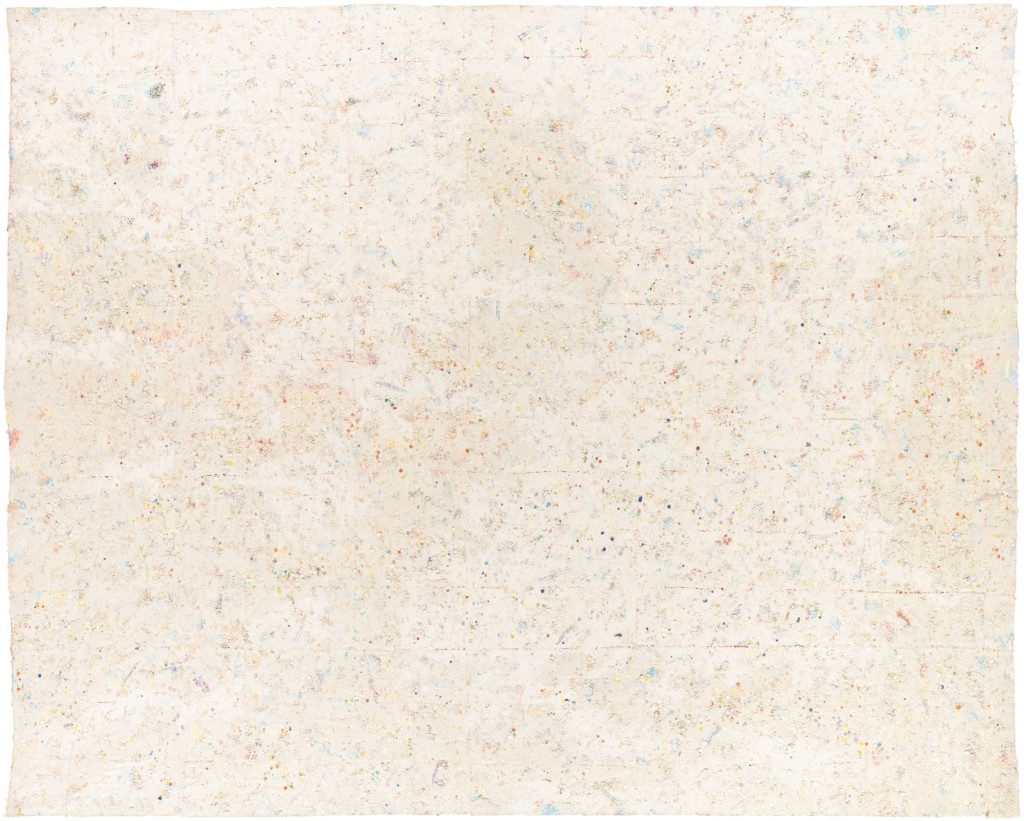

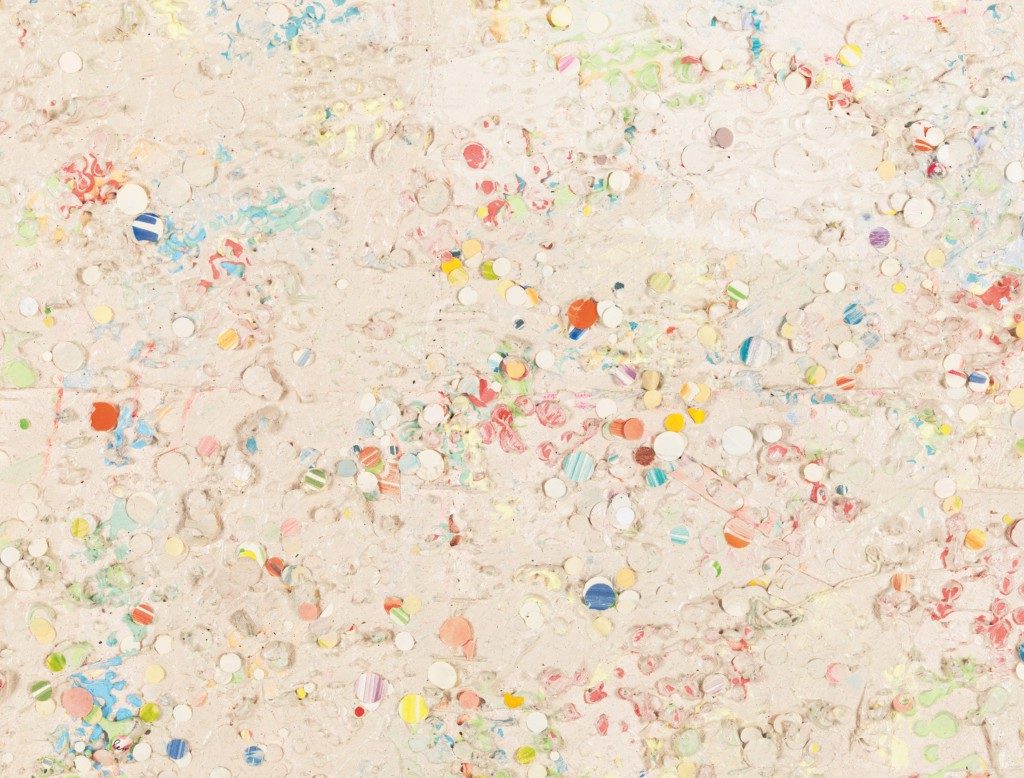

If this exhibition serves as an entrée into learning about the practices of influential black radical women, the knowledge offered goes beyond their courageous fights “against oppression on multiple fronts.”10 The sequencing of artwork within the exhibition insists on the makers’ deft experimentation with timely formal and conceptual approaches. Section four, dominated by atmospheric abstract paintings, attunes visitors to the oscillating optics of a work by Howardena Pindell, Carnival at Ostende (1977; figs. 4, 5). Hole-punched dots and acrylic encrust its canvas with curious effects; a label elaborates on them and Pindell’s methods. This gallery section is also where enticing, enigmatic performance art projects take hold. An installation of photographs captures moments from Senga Nengudi’s Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978; courtesy of the artist, Lévy Gorvy, New York, and Thomas Erben Gallery, New York) beneath an overpass in Los Angeles. Nengudi’s improvisational quasi-masquerade with fellow artists of Studio Z presages the final sections of the exhibition, in which videos of performances, films, and photographic series dismantle bourgeois social norms.

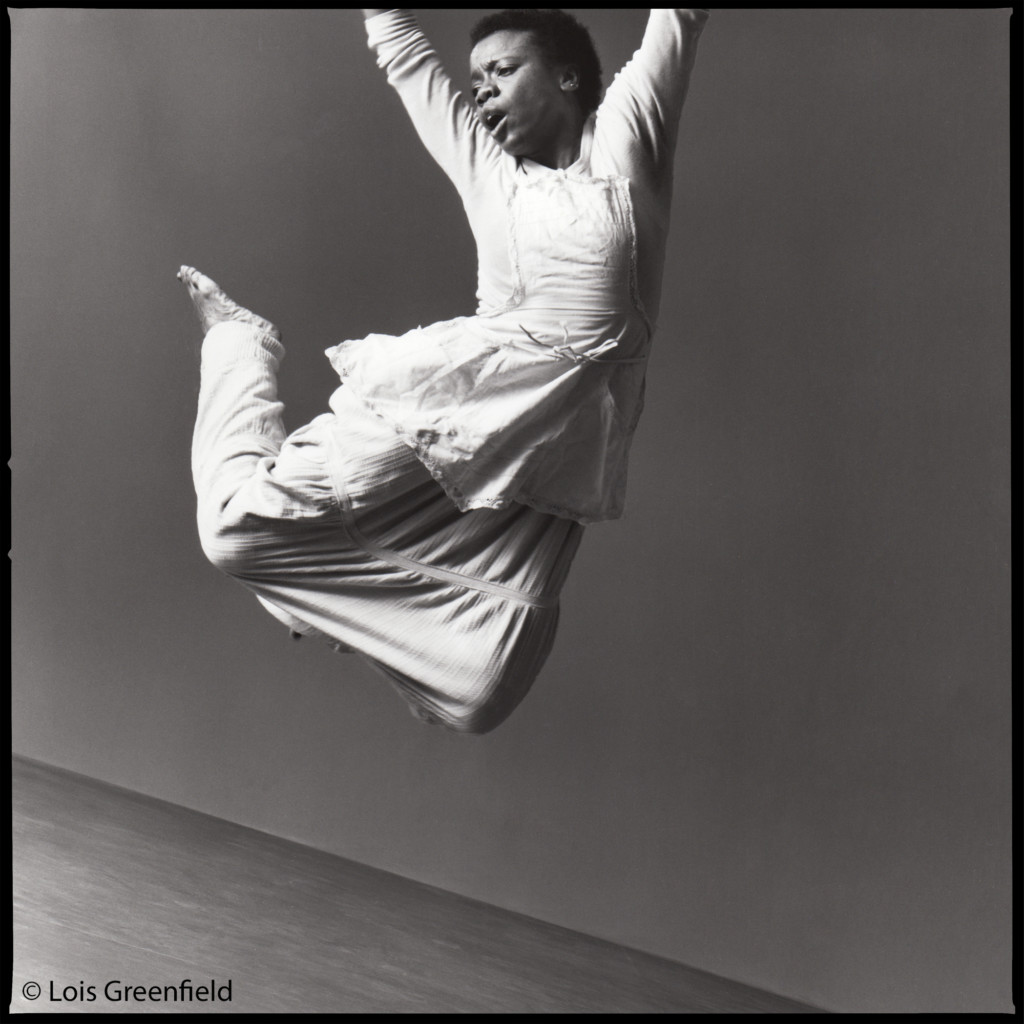

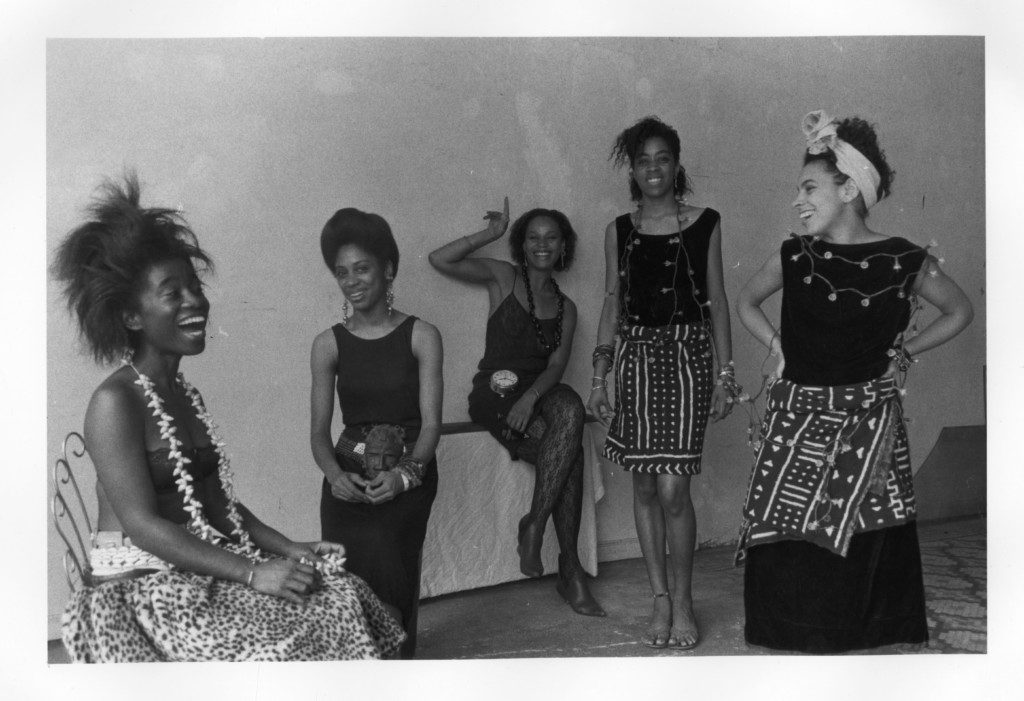

Visually dramatic and often witty, the works that close the exhibition subvert prevailing cultural narratives by retelling them through the artists’ subjective points of view. Touchstones by mavericks such as Lorraine O’Grady, Lorna Simpson, and Carrie Mae Weems shine alongside lesser-known but no less piercing gems. A range of personal strategies is evident too. The layout ushers visitors from the 1983 video recording of Chicken Soup (1981; New York Live Arts, New York), Blondell Cumming’s sparse and mesmerizing spasmodic dance interpretation of domestic work, to ephemera from the Rodeo Caldonia High-Fidelity Performance Theater collective’s maximalist plays (figs. 6, 7). As much as these juxtapositions amplify different signature styles, everywhere text informs us how many of the artists shown cultivated their careers with the aid of Just Above Midtown Gallery’s Linda Goode Bryant and other mutual partners.

A significant portion of the texts and other documents from We Wanted a Revolution appear in the skillfully edited compilation We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965–85 / A Sourcebook, which will surely invigorate the historical afterlife of the exhibition. A Sourcebook and the exhibition symposium at the Brooklyn Museum (as well as the forthcoming publication deriving from the symposium presentations) reinforce the large extent to which close-knit professional and political circles enabled the production of the art on view.11 These insights into coalitions of black women within inhospitable art and social ecosystems strike a chord with Kara Keeling’s writing on revolution. Citing Angela Davis’s 1971 essay “Reflections on the Black Woman’s Role in the Community of Slaves,” Keeling argues that a notion of meaningful resistance limited to total victory or total self-sacrifice, “devalues the tactics used by those who forged ways of sustaining life and communities in the face of violence, exploitation, and oppression.”12 We Wanted a Revolution mines such life-affirming tactics. It stages breakthroughs of the contributors’ practices conjointly with the histories of black women’s political organizing that underpin them. Still far from satisfied, these artists’ revolutionary desires are worth making our own.

Cite this article: Kim Bobier, review of We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85, Brooklyn Museum, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 3, no. 2 (Fall 2017), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1625.

PDF: Bobier, We Wanted a Revolution

Notes

- Morris and Hockley, “Revolutionary Hope: Landmark Writings, 1965–85,” in Catherine Morris and Rujecko Hockley, eds., We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965–85 / A Sourcebook (Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum, 2017),17. ↵

- Michele Wallace, “For the Women’s House,” 1972 interview with Faith Ringgold in Invisibility Blues: From Pop to Theory (New York and London: Verso, 1990), 40. This interview is reprinted in We Wanted a Revolution,102–13. ↵

- Ibid., 34–43 ↵

- Ibid., 41–42. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, “The Combahee River Collective Statement” in Barbara Smith, ed., Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, Inc., 1983), 273. ↵

- Kay Brown, “‘Where We At’ Black Women Artists,” Feminist Art Journal 1, no.1 (April 1972): 25. ↵

- Lorraine O’Grady, “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” Afterimage 20, no. 1 (Summer 1992): 14. ↵

- Holland Cotter, “To Be Black, Female and Fed Up with the Mainstream,” New York Times, April 20, 2017, C21. ↵

- Morris, “Struggling for Diversity in Heresies,” in We Wanted a Revolution, 186. ↵

- Morris and Hockley, “Revolutionary Hope,” in We Wanted a Revolution, 17. ↵

- To watch the online video-recording of the daylong symposium, We Wanted a Revolution, April 28, 2017, at the Brooklyn Museum see: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLzOFu6-OQMyPuYTxnUh7V–efyjP5vJqi . A volume of new essays, flowing from this symposium, is forthcoming. ↵

- Angela Davis, “Reflections on the Black Woman’s Role in the Community of Slaves,” The Black Scholar 3, no. 4 (December 1971): 2–15; Kara Keeling, The Witches Flight: The Cinematic, the Black Femme, and the Image of Common Sense (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 138. ↵

About the Author(s): Kim Bobier is a doctoral candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.