Peripheral Prints: Karamu House and the Rise of African American Art in the Midwest

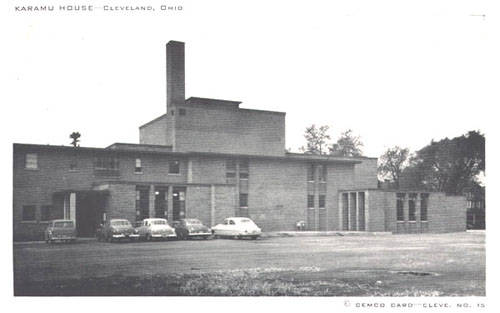

Cleveland, Ohio, was a vital, though overlooked, center of print production. Relatively inexpensive to produce and to purchase, prints were a central part of the US art market by the middle of the nineteenth century. And yet, scholarship has marginalized the history of print in Cleveland, a city haunted by deindustrialization and segregation, paying far greater attention to artistic activity in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Cleveland’s status as a center of print production arguably began as early as 1919 with the establishment of the philanthropic Print Club hosted by the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA)—the first of many such organizations that were formed at museums across the country.1 During the 1930s and ’40s, Cleveland grew to prominence as a print center when it was established as one of only five Federal Art Project (FAP) print shops by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The city was also home to the Cleveland Print Makers, whose print subscriptions introduced the Cleveland middle class to affordable art collecting. But most significant, Cleveland was also the location of Karamu House (fig. 1)—one of the earliest and most important Black community and performing arts centers in the United States and the site from which most African American artists in Cleveland got their start.

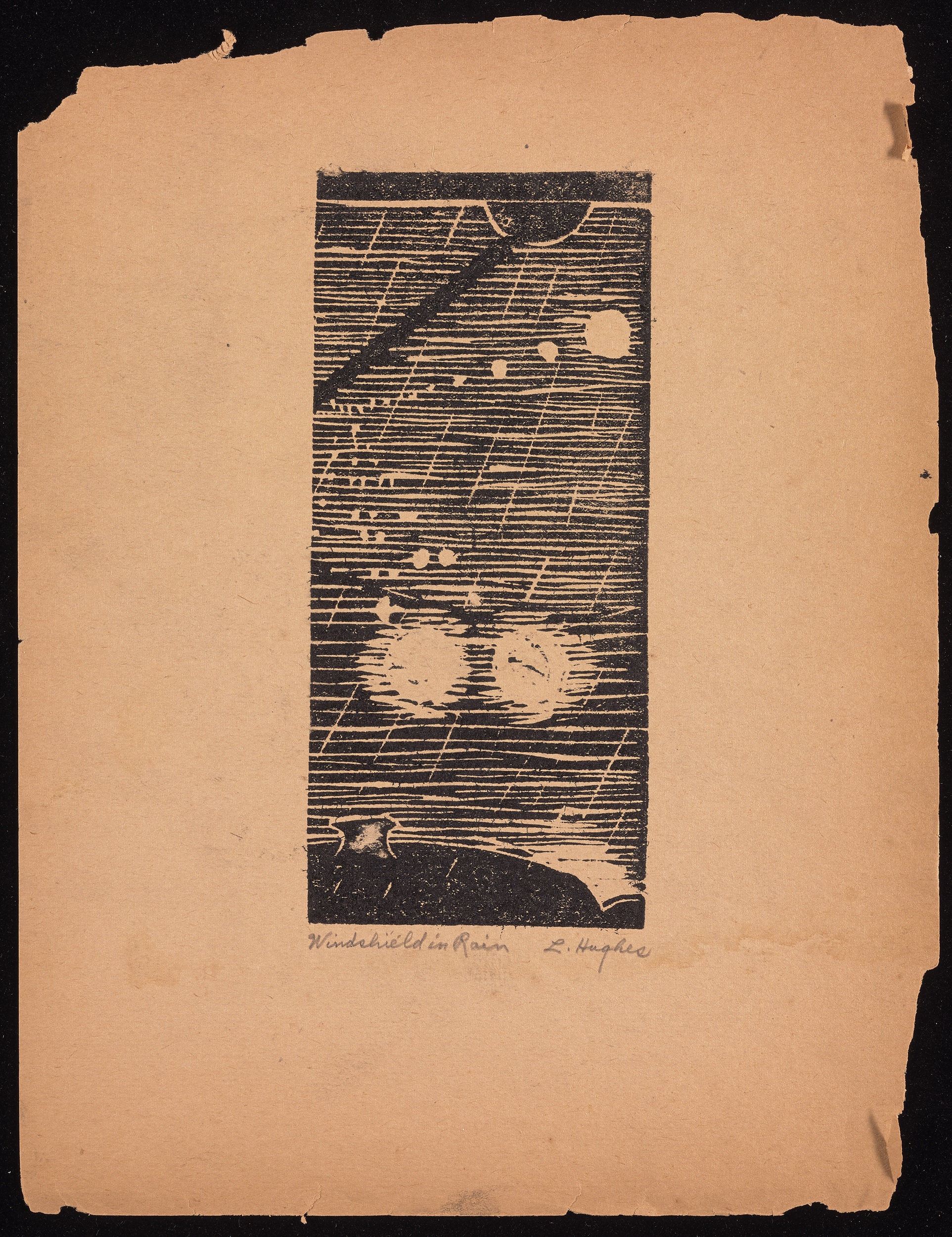

Initially founded as a settlement house in 1915 by two white sociologists, Russell and Rowena Jelliffe, Karamu House quickly became an important community arts center in the “Roaring Third,” the district that at the time was considered one of the worst slums in Cleveland.2 By the late 1930s, the famed Gilpin Players of Karamu House regularly staged the plays of Cleveland resident Langston Hughes (1901–1967), whose support of Karamu helped to establish its national reputation. At Karamu House, Hughes worked alongside a number of important Black visual artists, producing linocuts with Charles Sallée, William E. Smith, Elmer William Brown, Hughie Lee Smith, and Zell Ingram, all of whom came out of the Karamu House visual arts programs (fig. 2).3 These prints and the workings of the Karamu print shop, market, and gallery offer understudied evidence of what was, by the 1970s, an important destination for Black artists traveling across the United States. The Karamu House archives, now dispersed among several Cleveland institutions, quietly telegraph the impact of the Graphic Arts Workshop, where Romare Bearden, Moe Brooker, Jacob Lawrence, Nelson Stevens, Curlee Raven Holton, and other prominent Black artist-printmakers visited, taught, worked, and exhibited. While the Karamu print shop has long since dissolved, the prints themselves archive its history as an overlooked center for Black artists of both the Harlem Renaissance era and the Black Arts Movement.

Excavating and looking at these prints anew is not simply a matter of shedding light on a little-known site of Black art making. In some ways, the prints of Karamu House artists were, in fact, similar to those of other Black printmakers whose careers were launched at FAP-sponsored centers, such as Charles Alston and Norman Lewis in New York or Samuel Joseph Brown and Dox Thrash in Philadelphia. All of these artists made prints in a variety of mediums and focused on the themes of labor, urban squalor, and aspects of Black life. Further, all balanced their own individualized styles with the accessible Social Realist syntax demanded by the WPA-FAP. In his foundational publication Modern Negro Art (1943), James Porter identifies Karamu House as a veritable bastion of artistic productivity—dedicating an unusual amount of textual space to such a regionally specific group.4 What warranted Porter’s attention and what was unique about Karamu House, I argue, were the social and economic mechanisms that facilitated the professionalization of Black artists in Cleveland, despite the lack of any unified visual style in the collected works of Karamu House artists. What made Black artists in Cleveland “modern” invariably shifted over the decades, but remarkably, Karamu House remained central, shaping a trajectory for Black artists of the Midwest that was not conditioned by the WPA and was, I contend, dictated by the emergence of a Black art market in Cleveland.

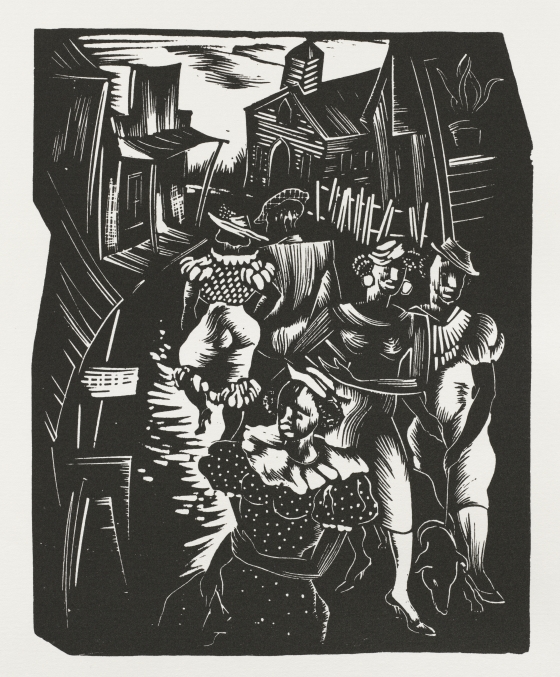

Lithographs, etchings, woodcuts, and linocuts made by Karamu House artists throughout the 1930s and ’40s have been the subject of very little scholarly consideration.5 Like the work of better-known Black printmakers, such as Aaron Douglas (1899–1979) and Hale Woodruff (1900–1980; fig. 3), these prints often convey images of Black life, and scholars have subsequently compared them with the Social Realist work of white artists, like Thomas Hart Benton or Grant Wood. By focusing on their potentially Social Realist content, however, scholars have disempowered the Karamu images, circumscribing their aesthetic efficacy solely in terms of their ability to foster racial empathy in the hearts of predominantly white viewers. In this art-historical model, prints by Sallée, W. E. Smith, Ingram, and others are persuasive examples of the geographic and racial breadth of the American Scene style, but the images do little else. In reality, however, prints by Karamu House artists did far more than ease racial tensions among a still largely, though unofficially, segregated population.

Despite a debilitating fire—likely the result of arson and a sign of entrenched local racism—and subsequent relocation in 1949, Karamu House grew to national recognition as a theater and as a center for visual artists from the 1950s through the 1970s. Rather than cleave to the broad trajectories of WPA-FAP–supported community art centers, Karamu House differentiated itself from prominent places of African American art making by continuing to emphasize the professionalization and accreditation of its artists and by building a Black clientele for the work they sold. Frequently omitted from histories of the Black Arts Movement, just as it has been from narratives of printmaking, Cleveland became an important site for the cultivation of Black cultural capital, with Karamu House at its core. Printmaking, thus, played an important and understudied part in the social and racial circumstances of art making in this milieu for two primary reasons. First, print is a historically collaborative medium that lends itself to the community-based practices that are integral to urban community art centers. Second, by virtue of their inexpensive, easily disseminated format of the multiple, prints offer an affordable entry into art collecting—a point that has been repeatedly made with regard to the democratization of art among white American collectors, but this idea has rarely been applied to the establishment of a Black collecting class.6 Karamu House fostered a Black middle-class art market that endured into the 1970s and 1980s, long after the democratizing effects of the WPA-FAP print shops had faded from US consciousness. It also worked to professionalize Black artists through the development of a vital social network and the statutes of legal incorporation.

Karamu Artists, Incorporated

During the 1930s, federally funded programs run by the WPA and local community art centers increased access to printmaking for artists and introduced the middle class in the United States to an affordable form of collectable art.7 Although the impact of the WPA-FAP programs on the history of print has been well documented, less attention has been paid to the enduring impacts of these programs on Black artist-printmakers from the 1940s through the 1970s.8 For instance, Robert Blackburn’s training at the WPA Harlem Community Art Center in the later 1930s and his subsequent establishment of the Printmaking Workshop helped to introduce Black printmakers to the broader art world, but ultimately, access to presses was still extremely limited for artists of color.9 In Cleveland, that access came via Karamu House.

Beginning in the 1930s, Karamu House hired Richard Beatty and other professional artists to teach visual art courses on site.10 Among the class offerings were ceramics, painting, sculpture, enamel work, and printmaking. Numerous unpublished archival documents suggest that printmaking was one of the most popular classes, and yet it seems unlikely that the center owned a printing press during such a financially difficult time.11 Instead, classes were offered in relief printmaking techniques. Unlike lithography and etching, relief prints—made by carving into wood or linoleum, inking the surface, and printing on dry paper—do not require a printing press. Karamu House therefore provided access to carving tools and matrices, and it funded scholarships to the nearby John Huntington Polytechnic Institute, where students could learn etching and lithography.12 What printing did take place at Karamu House during this period seems to have been done largely in the medium of linocut—which used an inexpensive substrate that was often donated to Karamu House by nearby flooring businesses.13 Made from burlap or canvas coated with powdered cork, rosin, and linseed oil and mechanically pressed into sheets, linoleum was a relatively new and important commodity in rust-belt cities in the 1930s, where it was marketed as an affordable alternative to more expensive flooring options and thus heralded as a material that could bring “art to every room in the house” through vibrant patterns and designs.14 As a printmaking substrate that was itself made from linseed oil—the very binding medium that revolutionized painting in the sixteenth century—and as a material with both specific graphic qualities and potentially democratizing effects, linoleum has important and understudied theoretical implications that will be taken up at greater length below.

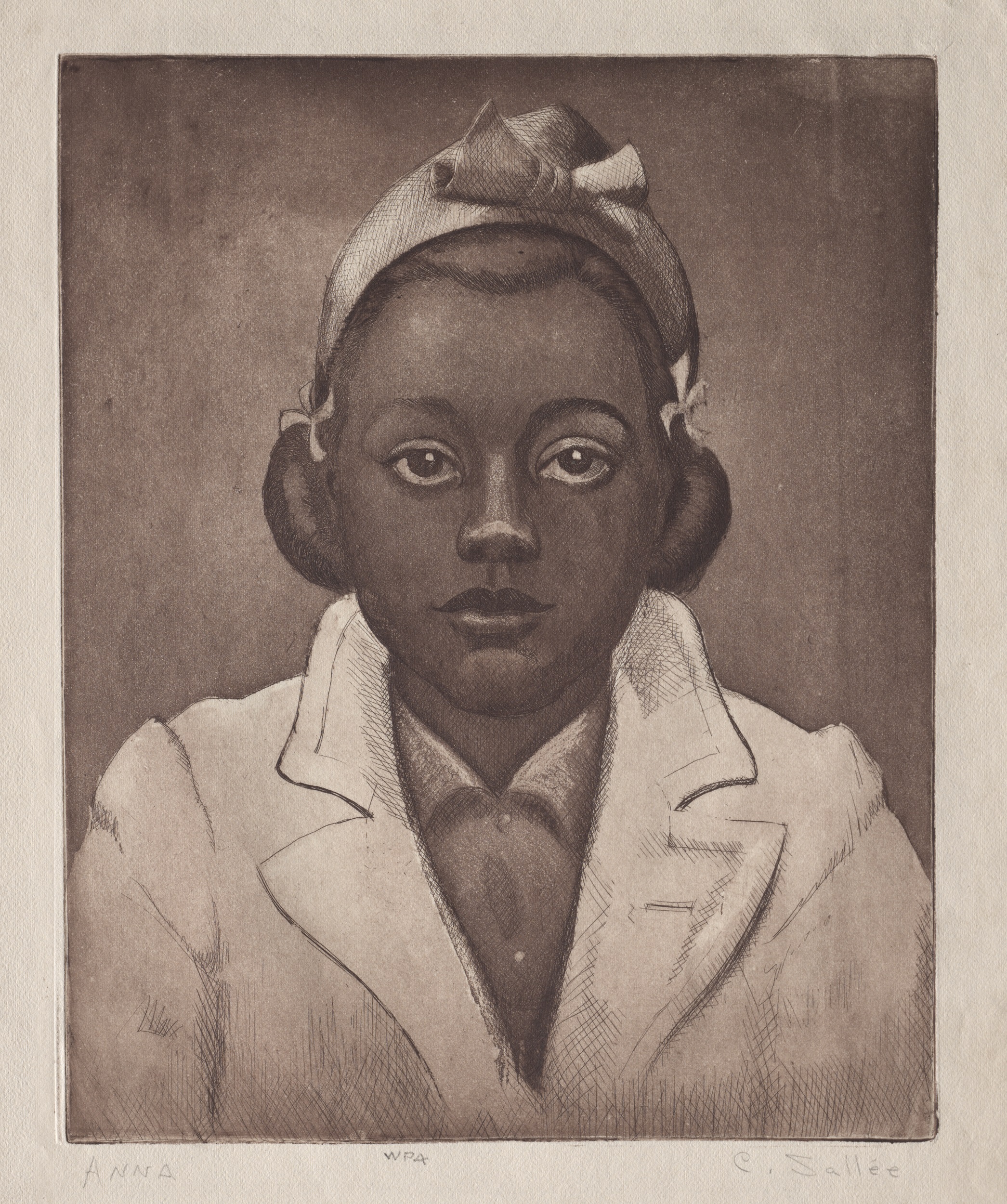

When Cleveland was established as just one of five US graphic art centers for the WPA-FAP in 1935, linocuts figured prominently in the artistic production of white and Black artists alike. Under the local direction of Kálmán Kubinyi, an instructor at the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art), the Graphic Arts Project of the WPA was first located at John Huntington Polytechnic, where Karamu artists Charles Sallée (1911–2006; fig. 4) and H. L. Smith were already enrolled. In turn, Sallée, Smith, and four other Karamu artists made prints for the WPA while simultaneously maintaining their affiliations with Karamu House. As Elizabeth Seaton’s research about WPA-era print history demonstrates, Black artists were also included in other FAP graphic art workshops, but they were in the vast minority—of the 789 artists employed to make prints for the FAP, only nineteen were African American.15 Notably, the Cleveland and New York workshops employed the same number of Black artists: just six in each city. Mirroring national statistics, the six African American members of the WPA print shop in Cleveland were outnumbered by sixty-nine Caucasian members.16

Kubinyi’s unusually successful leadership of a cohort of printmakers introduced Clevelanders to affordable print subscriptions, portfolios, print markets, and collecting opportunities that existed in tandem with the operations of the federally sponsored and controlled Graphic Arts Project.17 Although congress voted to defund the FAP in 1939–40, Kubinyi kept the Cleveland workshop afloat for several more years, facilitating the purchase of prints without restrictive governmental oversight. By 1941, Kubinyi had to concede defeat, however, and his organization disbanded. In previous studies of US prints and the WPA-FAP, and in the scant literature about Karamu House artists, scholars have implied that fine art printmaking ceased to exist in Cleveland with the total dissolution of the WPA-FAP in 1941.18 This inaccurate conclusion is refuted, however, by t.he formal incorporation of Karamu Artists Inc. in this exact year, signaling the ascent rather than the decline of Black printmaking in 1940s Cleveland.19

By their own description in their constitution and bylaws, Karamu Artists Inc. was “a group of Negro artists who were quietly and almost unnoticeably unparalleled anywhere else in the United States.” They state that, through the efforts of Karamu House and the Gilpin Players, “there has grown into maturity the largest group of producing Negro artists of standing in the country according to Alain Locke of Howard University, Washington D.C. The professional stature of this group of six Negro artists is based solidly upon achievements ranging all the way from prizes to places in museum collections. The group is unique in that each member has won outstanding professional approval.” In these previously unpublished legal documents, Karamu Artists Inc. establish that their purpose is to “bring the work of Karamu artists before the public” and to “spread art appreciation throughout the community and the nation.”20 In this way, Karamu Artists Inc. almost certainly saw the greater alignment of their purpose with the democratizing efforts of the FAP, which had, for the latter part of the 1930s, emphasized access to art across all socioeconomic strata. Unlike other locations of the Graphic Arts Project in New York or Philadelphia, the African American alumni of the WPA-FAP in Cleveland distinctly banded together to foster a Black arts infrastructure.

As a subsidiary of Karamu House, Karamu Artists Inc. operated in a fundamentally different way from other Black community art centers of the 1940s: Karamu Artists Inc. functioned as a visual arts branch of a center otherwise dominated by the performing arts; their intention from the outset was to run a profitable business so that Black artists could be properly recognized as professionals; and they foregrounded the role of the print medium (over other socially engaged media, like murals) as a component of their economic model. Like other WPA-era community art centers, such as Sommerset in Pennsylvania, the Fine Print Workshop in Philadelphia, and the Harlem Community Arts Center in New York, Karamu artists recognized in the print medium an opportunity to cultivate Black artists as thriving professionals, even without the support of WPA funds, which were retracted from all of these centers by 1943. Although the Southside Community Art Center, founded in 1940 in nearby Chicago, was also a settlement house and an artistic incubator for emerging Black artists, it did not run a for-profit theater on site, nor did it apparently work in tandem with local Black-owned galleries to shape a Black art market in Chicago in the 1960s through the 1980s.21 As such, Karamu Artists Inc. was unique in both its inception and because Karamu House itself continued to act not only as a physical site for the creation and display of art but also as an economic driver in the Black arts economy of Cleveland.

Karamu Artists Inc. planned for Black artistic success in Cleveland by including “one man shows, group shows, exchange exhibitions, formation of a free art lending society and issuance of a series of print portfolios to be sold at a nominal cost.”22 Membership to Karamu Artists Inc. was available to any artist able to pay the monthly fee of sixty cents, which entitled artists to a free one-person show and participation in the biannual group show. Notice of the establishment of Karamu Artists Inc. appeared in the Cleveland Plain Dealer newspaper in July 1940, just a month after their formal incorporation. Arts writer Grace V. Kelly was quick to note that the success of artists included in this group stemmed from their professional training at established arts institutions, including the Detroit Society of Arts (H. L. Smith), Connecticut Academy of Fine Arts (W. E. Smith), and Western Reserve University (Sallée).23 Further, each artist in the group had been recognized in the Cleveland Museum of Art annual May Show. A juried exhibition of local artists that ran until its dissolution in 1993, the May Show was the annual benchmark for northeastern Ohio artists who wished to establish their professional credentials; all but one of the artists of Karamu Artists Inc. had exhibited their work at the May Show by the later 1940s.

The resounding success of Karamu Artists Inc. was recognized by the CMA in 1941 when it staged an exhibition of Karamu House graphic artists, for which each artist wrote his own descriptive labels.24 The prints were also available for purchase and priced modestly, ranging from five to twelve dollars each. Although the exhibition included several drawings and watercolors, the vast majority of the prints were linocuts.25 Subjects ranged from portraits, to poignant personal vignettes, to scathing social commentary.

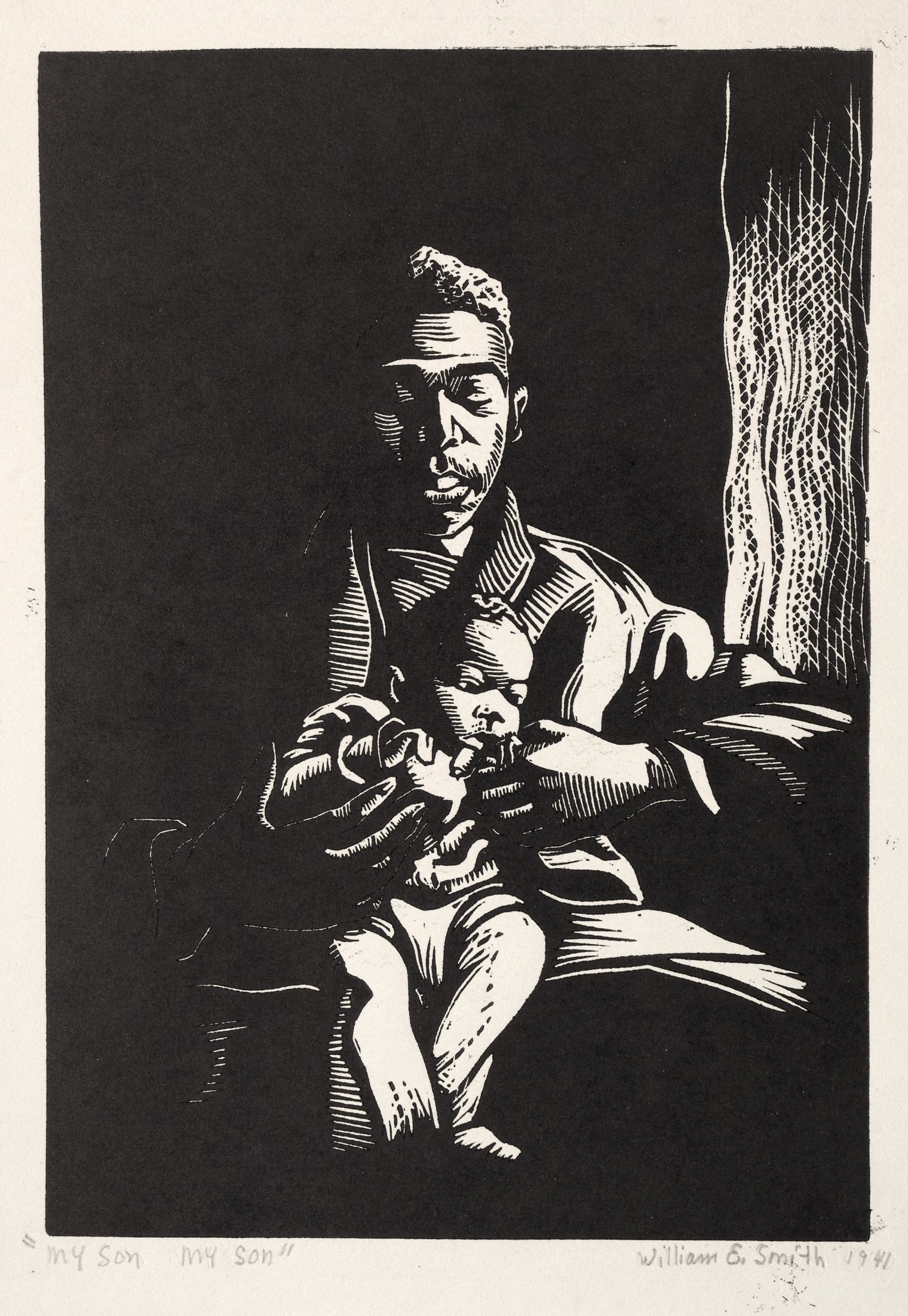

In his linocut titled My Son! My Son! (1941; fig. 5), W. E. Smith (1913–1997) depicts a young father tenderly holding his infant son. Smith expertly uses the uncarved portions of the block to isolate the figures, who emerge from the inky depths of the sheet. A roughly cross-hatched curtain suggests a domestic interior, and the father’s splayed elbows seem to rest on invisible chair arms. Although serene, the father’s fatigue is palpable—his downcast eyes shadow his cheeks, and his massive hands cradle the child. Smith’s accompanying text explains, “I saw a man with large rough hands handling his infant son with great tenderness. I knew that he thought of the life that was ahead of his son, and wished that it might not be as cruel for the son as it had been for him. I knew at that moment that this is the wish of every parent. I wanted to get this into my print, as well as the joy of the child in being close to the father.”26 Smith’s image is both hopeful and foreboding, embodying both the universal joy of parenthood and the particular vulnerability of the Black family.

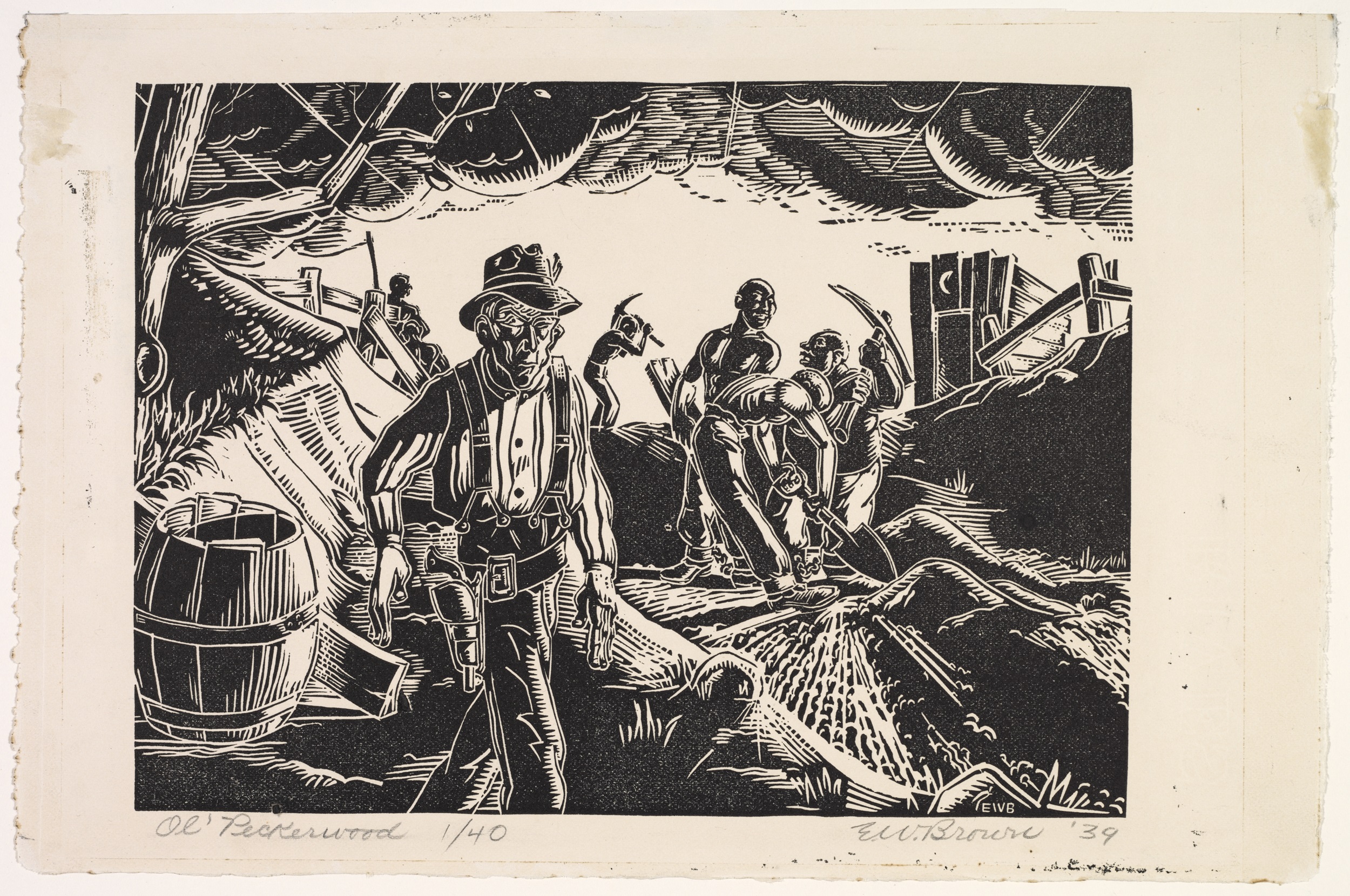

Other linocuts in the CMA exhibition were more explicit in their depiction of the violence of Black life. In Ol’ Peckerwood (1939; fig. 6), Elmer William Brown (1909–1971) communicates the horrors of his experiences in a Missouri prison. “When I was fifteen years old,” Brown writes in his label, “I was sentenced to a chain gang, because I had been caught riding a freight train. I was strong and husky and probably looked as though I was good for a lot of work. The gang was working in the region of Oakdale, Tennessee. The overseer we dubbed, ‘Old Peckerwood,’ which generally means ‘poor white trash.’ He was tough, and hard as nails. I have never hated anyone so much in my life.”27 Hunched and emaciated, Peckerwood looms in the foreground of Brown’s print and stares vacantly out at the viewer, his limp hands and holstered gun rendered impotent. Peckerwood is wrinkled and decrepit—his moral impoverishment is highlighted by the shackled, muscular Black prisoners toiling in the middle ground. Haloed by the luminous sky and foreboding clouds, the figures in Brown’s print offer a moralizing meditation on the objectification and brutalization of the Black body.

Brown liberates the figures from their restrictive plight with his use of soft, pliable linoleum. Receptive to the lightest pressure or blade, linoleum offered Karamu House artists access to a medium that did not require specialized tools and that facilitated illustrative, sinuous line making. Linoleum was first used as a print matrix around 1917 when German and French Expressionists experimented with the direct, spontaneous quality of line achievable with simple carving implements. Under the stewardship of British artist Claude Flight, founder of the Grosvenor School in London (1925), linoleum was heralded as the ideal medium for democratizing art production, because it could be carved with household implements and printed at home with little to no formal training or expertise.28 W. E. Smith, for instance, used both a traditional gouge and nontraditional carving tools—including a sharpened umbrella stave—to make his images. Without an imposing woodgrain, linoleum can be carved away in clean, curvilinear shapes, leaving flat, uninterrupted expanses behind. Ink easily adheres to its waterproof surface and transfers cleanly to paper without the need for specialized equipment or the powdered inks that are often used in Anglo-Japanese woodcut-printing techniques. Linocuts like those by Brown and W. E. Smith are therefore graphically sharp, and flat, opaque expanses of inked tone accomplish a similar effect as that achieved with screen print, a medium that later became synonymous with Civil Rights activist printmaking.29

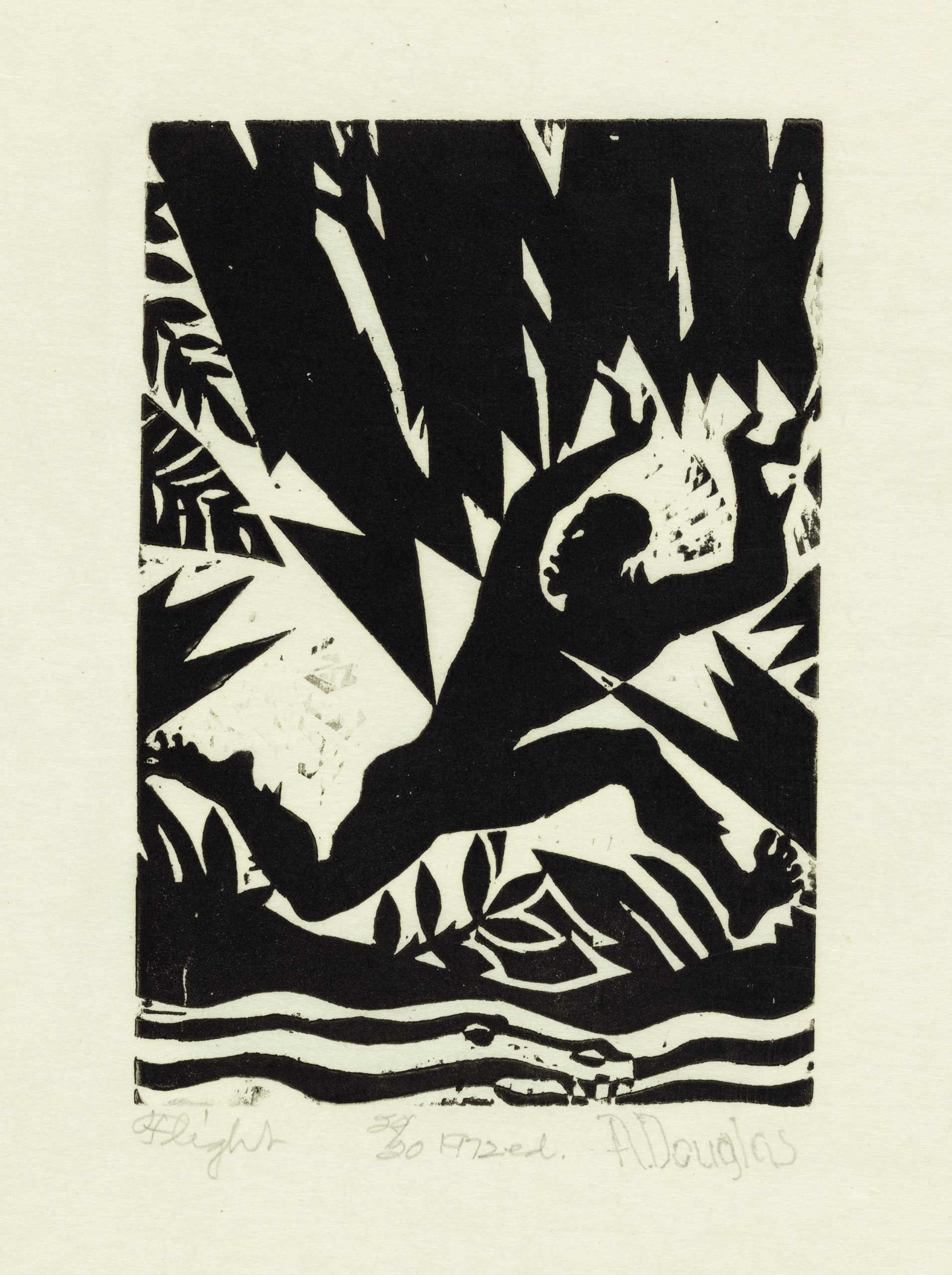

Linocut, however, was not only appealing for its cost efficiency; it was also capable of communicating in a distinct graphic style that led Henri Matisse to characterize it as the “true medium for the painter illustrator.”30 The visual effect of linocut is, as Matisse recognized, quite different from woodcut. In his Emperor Jones series, for example, Harlem Renaissance artist Aaron Douglas created bold figural compositions that reverberate with the inked traces of unrelieved wood grain (fig. 7). Scattered protrusions into the negative carved space of the blocks contribute to the urgent, organic chaos of Douglas’s scenes from Eugene O’Neill’s 1926 play of the same title. In Douglas’s series, the expressive potential of woodcut is harnessed to evoke the harsh setting of O’Neill’s play in the West Indies and to depict moments of an epic battle between humankind and nature. Karamu Artists Inc. also illustrated scenes from well-known plays, but linocut offered them a crisp, clean alternative to the grainy irregularity of wood.

Karamu Artists Inc. were certainly not the only Black printmakers of the 1930s and ’40s to exploit the inexpensive and graphically appealing medium of linocut. Both Hale Woodruff and later Elizabeth Catlett used linocut to depict the brutality and inequity of racial violence in Jim Crow–era United States. Having trained under the Taller de Gráfica Popular (People’s Graphic Workshop) in Mexico, Woodruff and Catlett also understood printmaking in general, and linocut in particular, to serve a political function, capable of fomenting social change. Karamu Artists Inc. might have similarly capitalized on the stark visual terms of linocut for its rhetorical appeal. When Karamu artist Zell Ingram contributed images to the periodicals Opportunity: The Journal of Negro Life and The Crisis, he selected the schematized linear effects of linocut. Ingram and Brown also printed most of the Karamu House Gilpin Players playbills and the covers of several of Hughes’s plays, all in linocut.31 Linocut was the graphic vehicle of Cleveland’s only Black theater and performing arts center, a central technique of its visual artists, and therefore a distinctive aspect of the emerging Karamu House aesthetic brand.

Despite the fact that linocuts were also criticized for their comparatively simple technique and deemed “childlike” by some critics, Karamu House seems to have holistically embraced the medium.32 The appearance of technical naivete in linocuts is, of course, misleading, since it, like all relief printing, requires careful and systematic knowledge of principles of design, reversal, and registration. Paradoxically, relief produces the effects of a drawn surface by inverting the drawing process itself. The marks made by the carving implement—whether umbrella stave or gouge—are not printed as lines. Instead these channels of unseen substrate recede, while the planes of intact block receive the ink. In the capable hands of the Karamu Artists Inc., the metaphorical connotations of the relief medium are particularly resonant: neither naive nor childlike, the adept relief of white negative matter yields to the positive, Black image on paper.

Displayed alongside the artists’ “descriptive paragraphs” at the 1941 exhibition at the CMA, the Karamu artists’ linocuts and other prints offered poignant testimony of their lived experience. They also worked to foster racial empathy through their tender description of the hardships of Black life, conforming with a type of biographical exhibition practice that was to dominate racialized museum practices throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.33 Through the depiction of specific, intimate moments, such as that conveyed by Smith’s poignant My Son! My Son!, Karamu artists, however, also pushed the graphically stark, unequivocal medium of linocut to new ends. Leveraging the opportunities offered by the coalition of Karamu Artists Inc., these artists created prints that, taken together, constituted an unprecedented assertion of the value of Black life rather than its simple documentation.

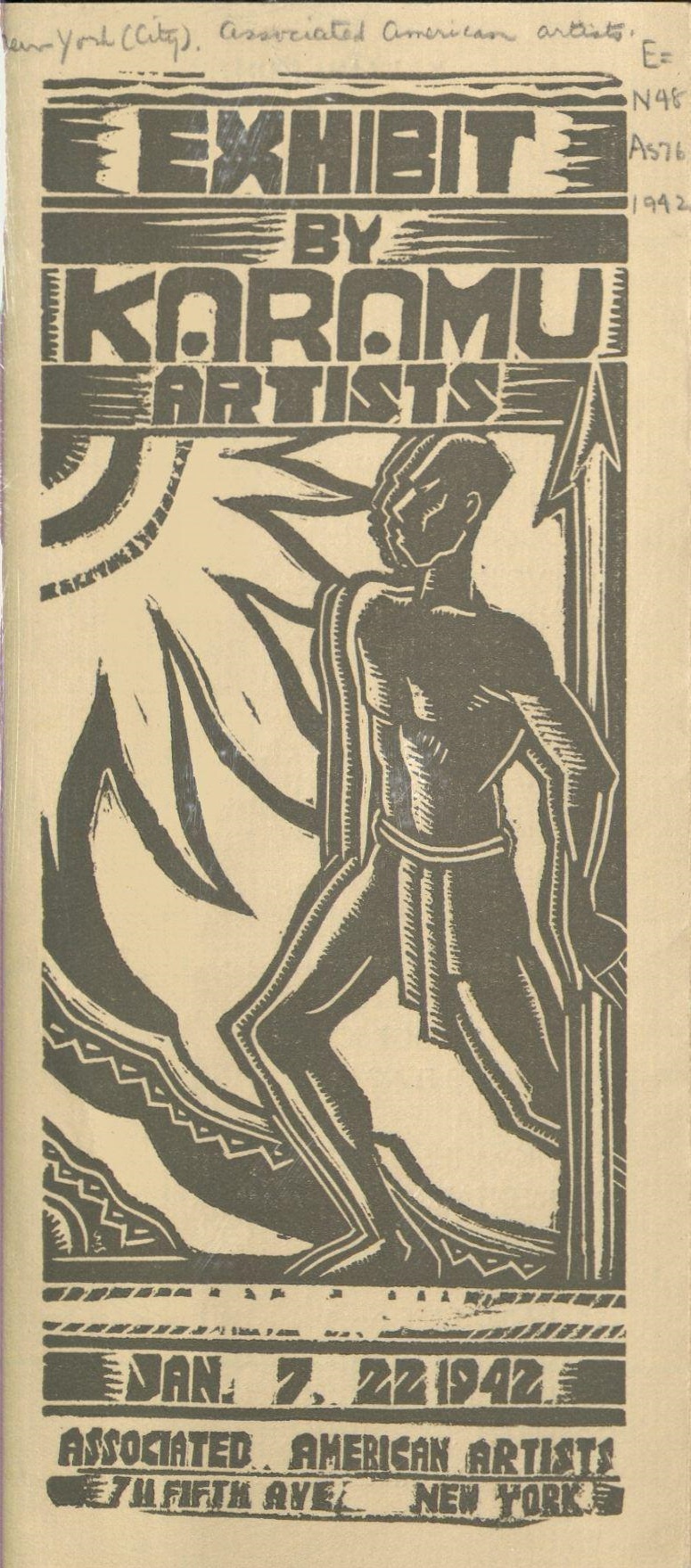

The CMA exhibition closed after just six weeks, but in January 1942, the Associated American Artists Galleries in New York hosted an exhibition of Karamu artists that featured many of the same objects that the smaller Cleveland show had. The New York exhibition assembled roughly 135 prints (lithographs, etchings, and linocuts), ceramics, metal and enamel work, paintings, pastels, and drawings by Karamu Artists Inc. and their associates; it was nearly triple the size of the CMA show. Founded in 1934 with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt as honorary chair, the Associated American Artists (AAA) was a for-profit business that famously sought to bring art into every American home, from “studio to doorstep.”34 Although the AAA is best known for its distribution of inexpensive editions of American Scene prints, their New York gallery also fulfilled a similar mission to “bridge the gap separating the artist from his audience.”35 The 1942 Exhibition by Karamu Artists therefore hoped to introduce broader US audiences to “a group of young men who have grown up and worked together through a period of years with common ideals and goals and, therefore, constitute a growing ‘school of art.’”36

An accompanying pamphlet for the show (fig. 8) trumpeted that this was the “first presentation of its kind in America,” presumably because it featured a group of artists who, by virtue of their association with and training at Karamu House, could be considered a “school” in conventional art-historical terms. Such a declaration also entirely erased the true “first presentation of its kind,” which, of course, had taken place in Cleveland the year prior. The wording of the AAA predictably centers New York as the location for artistic and racial progress, while Cleveland is shunted to the side.

As the pamphlet further clarifies, Karamu House used its arts program to accomplish two ends:

First, the direction of the Negro’s creative abilities into the main stream of American life, thus removing him from the isolation which has been so costly to initiative and ambition. Secondly, to enable the Negro to tell his own story to the community and the nation, making directly known his sufferings, dissatisfactions, his aspirations and ambitions. . . . In all the art endeavors of Karamu there is the conscious effort to retain and use the particular experience of the American Negro, to capture the essential Negro quality.37

Although the “essential Negro quality” is not defined by the pamphlet, the AAA exhibition conformed with other notable exhibitions of the 1930s and ’40s that similarly sought to acquaint the “mainstream” (that is, white) public with Black creative expression as a means to accomplish two social goals: to elucidate the perils of Black life and to better integrate and assimilate the Black population in the United States.38 A perforated donation form printed on the exhibition flyer assured visitors that their contributions to Karamu House would evidence the “spirit and principle of democracy” encoded in their charitable giving.39 Such giving was not, however, tied to the aesthetic value of the works of art in the exhibition, nor did it cultivate a network of patronage for the artists whose work was on view.

Through their exhibition and distribution in printed form, images like those by Brown and William E. Smith engaged with an evolving definition of Black art that centered life experience and promoted the Black artist as a “translator” whose primary function was to create a “visual analog of Black life” to be consumed by non-Black audiences.40 In some ways, this function of Black art was circumscribed by Locke, Porter, Hughes, and the New Negro Movement itself, which offered the “promotion of Negro culture in its original form with proletarian content” as a vital part of the movement.41 Indeed, in his lengthy 1943 discussion of Karamu Artists Inc., Porter describes their collective contribution in terms of its “attack on the problem of social description and interpretation.”42 Karamu artists were a means to “demonstrate the value and equality of Negroes to a larger mainstream audience.”43 This thesis was borne out in their depiction of African American “subject matter” rendered from a “discerning perspective, creating empathetic representations chronicling social conditions . . . affecting their communities.”44 The artists of Karamu Artists Inc., however, did far more than document the historical reality of their experience—they staked out an original graphic language that was to have lasting implications for the development of a Black art market in the Midwest and for the professionalization of Black artists more generally.45

Beyond the WPA: Prints and the Black Art Market in Cleveland

The dismantling of the WPA-FAP in 1941 foregrounded the shortage of patronage and commissions for Black American artists.46 Although Porter writes optimistically about this change in 1943, affirming that “the opportunities afforded Black painters and sculptors so far through the WPA Federal Arts Projects raise the hope that equal opportunities will soon appear through private and commercial patronage and that the prejudice and mistrust . . . of black artists . . . will be abolished,” such opportunities were, in fact, few and far between.47 In the absence of WPA-FAP programs and democratizing opportunities for artists of all colors, community art centers and exhibitions highlighted the place (or lack thereof) of Black artists in conceptions of US art more generally, a phenomenon about which much has been written.48 The Harmon Foundation exhibitions of the 1930s and ’40s, the WPA-FAP, and early exhibitions of Black artists at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) and the Baltimore Museum of Art similarly introduced critics, collectors, and citizens to art by Black artists, but they also did little to incorporate Black artists into conceptions of art in the United States.49 By keeping Black artists largely segregated in solo and group exhibitions throughout the 1950s and ’60s, art institutions perpetuated an othering ideology that peripheralized Black artists and further distanced them from broader trends in American modernism.50

In some ways, the distinction between a “mainstream” American modernism and a Black art aesthetic was also reinforced by the Black artists themselves. As curator Lowery Stokes Sims writes, despite the “fact that modernist genres such as abstraction were grounded in African art, and . . . that black dance and music had ushered in a modern sound and sense of the body, African American artists of Africana descent were positioned as followers and imitators of white artists recognized as pioneers of modernism.”51 In turn, Black artists of the 1950s through the 1970s struggled to define what “Black art” might look like and in what ways it should emphasize the African continent as an aesthetic point of origin.52 Although the broader significance of African art for evolving conceptions of US modernism lies outside the scope of this article, the emergence of pan-Africanism permeated the history of Black art making in Cleveland in notable ways. For instance, during the 1950s and 1960s, the Cleveland Museum of Art Extensions Collection (today the Education Collection) curated loan shows at Karamu House, including several of African art.53 In a formal document of response from Karamu House dated to 1960, Karamu administrators celebrated the success of these exhibitions in fostering public interest in the arts and providing a source of artistic inspiration to resident artists.54 As has been well established, Black artists of this period increasingly pursued abstraction as a means of simultaneously finding artistic freedom and asserting African pride. Artists like Woodruff, previously known for his Social Realist prints, began employing a semiabstract style to recast “the art of the Negro” as pro-Africa and antiprimitive.55 Exhibitions of African objects at Karamu House and the inclusion of African source material in the work of the Karamu artists (discussed in greater length below) also worked in concert with the politics of the Black Arts Movement, whose proponents called for a Black cultural nationalism that reclaimed Africa as central to Black identity.56

The 1950s and 1960s were a period of severe economic and racial unrest in Cleveland. Yet as Cleveland faced its most polarizing period of racial strife and economic decline, Karamu House anchored the Black community. During the early 1960s, the Karamu House exhibition galleries welcomed tens of thousands of visitors and hosted artist visits by Romare Bearden, Gordon Parks, and Hale Woodruff. With the historic 1967 election of Carl Stokes (1927–1996), the first Black mayor in the United States, Cleveland provided a safe haven for African American artists, creatives, and intellectuals traversing the country. Archival evidence suggests that Karamu House continued to thrive as a community center and as an artistic incubator, a point that has gone unrecognized, perhaps because of its increasing focus away from WPA-era interracialism and instead toward attempts to assist the Black community. As Karamu House transitioned from a Midwestern center of the Harlem Renaissance to a harbinger of the Black Arts Movement, it ultimately became an integral driver of the emerging Black art market.

Prints continued to play a pivotal role in Karamu House’s visual arts program despite the fact that it had grown to national prominence primarily as a center for the performing arts (including theater, dance, and music). During the 1960s and 1970s, two primary models emerged for the making of prints in the United States.57 One was the collaborative press, where master printers worked with artists like Jasper Johns, Jim Dine, and Robert Rauschenberg to realize their abstract visions in printed form. The rise of Universal Limited Art Editions, Tamarind Workshop, Crown Point Press, and other major workshops in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco played a major role in the elevation of print as a viable (and valuable) form of contemporary art, so long as that art was largely abstract. The second model was the community-based arts center, which shared the same collaborative emphasis as the former but instead harnessed the potential of prints for the purposes of activism and advocacy. Artists’ collaboratives, such as AfriCOBRA (African Community of Bad Relevant Artists), the Royal Chicano Airforce, and the Third World Liberation Front, made posters and other printed images for advocacy of the Civil Rights Movement. With the help of artists like Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, Malaquias Montoya, and Esther Hernández, printmaking in the United States became explicitly tied to social activism.

Karamu House followed neither of these models. It was not a professional, collaborative print shop nor was it an amateur community art center with an overtly political printmaking arm. Instead, Karamu House was an integral social center for the formation of artistic identity—a place where young Black artists saw others who, according to artist Curlee Raven Holton (b. 1951), “looked like them,” where said artists could access a library of art-historical sources, and where prints were made and, more importantly, sold on site.58 Helmed by director Kenneth Snipes, Karamu House of the 1960s and ’70s was the artistic home of a new generation of artists, including Nelson Stevens, Holton, and Michael D. Harris, who benefited from the professional infrastructure first established by Karamu Artists Inc.

As H. L. Smith recognizes in an article published in a 1964 issue of Negro History Bulletin, formidable obstacles impeded Black artists from achieving success. In addition to general economic inequities, Smith asserts that the “Negro artist is painfully familiar with the ever-present necessity of finding adequate patronage. In its efforts to emulate the white middle class in the acquisition of status symbols, the Negro middle class has completely over-looked the importance of art.”59 Karamu House actively worked to combat this broader national trend throughout the 1960s and ’70s by continuing to offer on-site art classes, by hosting exhibitions, and by selling the work of young and emerging artists.60 In so doing, a peripheral, Midwestern locale became a generative bastion of Black artistic productivity at a time when artists of color were still marginalized by the mainstream art world.

In celebration of its fiftieth anniversary in 1965, for instance, a week-long festival returned alumnus Woodruff to Karamu House to expound on the “Role of the Arts in Human Relations.”61 Shortly after, in 1969, the Karamu House Women’s Committee mounted the first major local exhibition since the 1941 CMA show to concentrate on the work of Black artists. Black Printmakers ’69 brought the work of twenty-five Black graphic artists from eleven states to Cleveland (fig. 9). In a letter to a gallery manager, Snipes remarks, “Karamu House continues to stimulate interest in the virtually untapped reservoir of Negro creativity as a means of building racial understanding” in Cleveland and beyond.62 The goal, writes Karamu Art Coordinator Elmer Turner, was to “acquaint the sensitive and concerned public of Cleveland with the dramatic and unique work being done by the Black artists of the United States.”63 More than four hundred people packed the Karamu galleries on opening night.

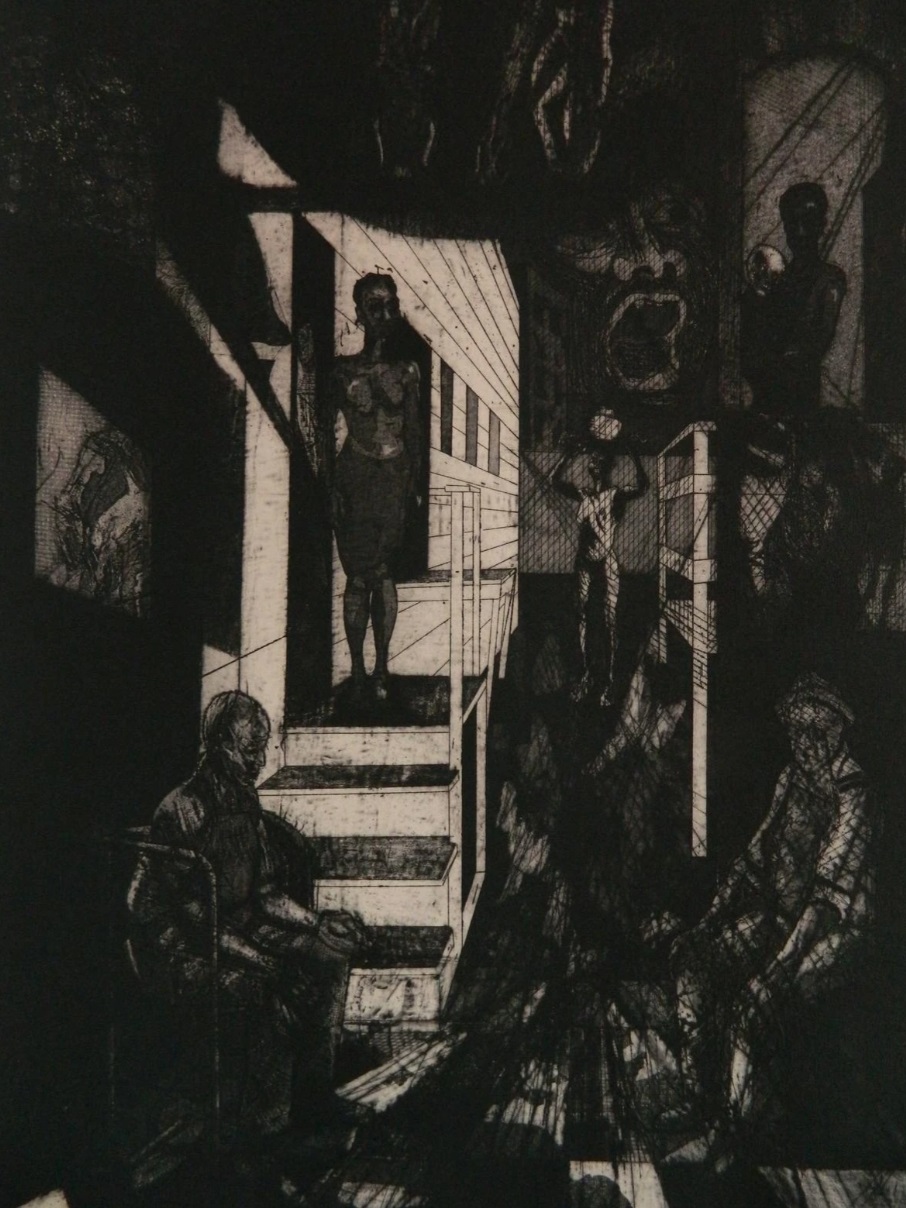

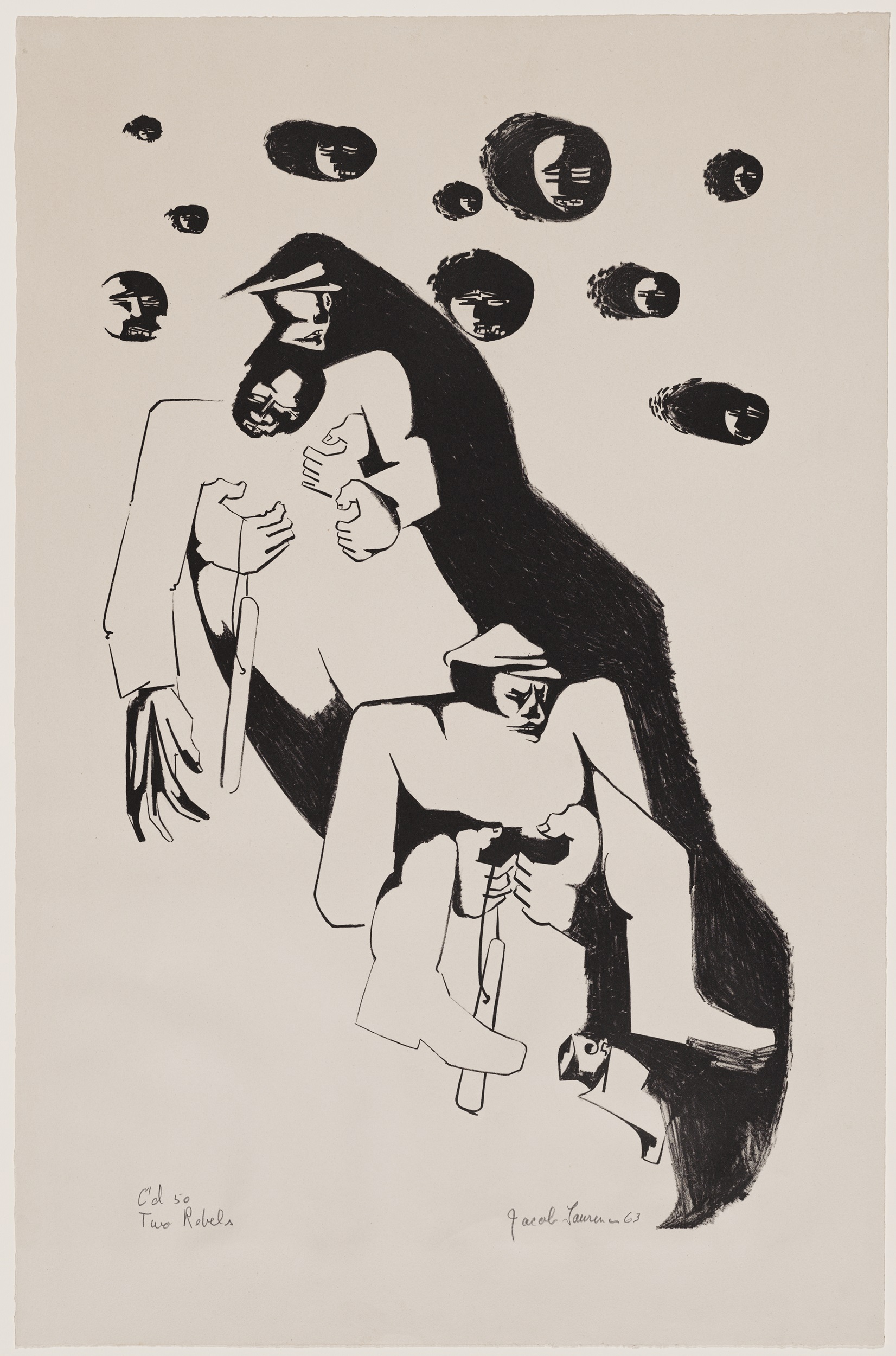

Black Printmakers ’69 featured the work of Wendell T. Brooks, Helen Evans, Moses Jackson, Nelson Stevens, Hartwell Yeargans, Jacob Lawrence, and others. A large number of the forty-two prints displayed focus on themes of oppression, emancipation, and African American identity, but unlike the earlier generation of Karamu artists, prints in the exhibition do not employ a Social Realist style but rather demonstrate new forms of figurative abstraction. Etchings by Leon Hicks (b. 1933; fig. 10) and Brooks (b. 1939; fig. 11), for example, employ the graphic potential of intaglio to depict the contorted, diseased head of a Black Appalachian man and a fraught scene of the US South, but both artists obfuscate easy visual reading by distorting “reality” with a matrix of finely wrought lines and fragmented planes. Similarly, Lawrence’s first known print, Two Rebels (fig. 12), a lithograph after a painting of the same title, depicts a figurative subject torn from Civil Rights–era headlines, but the artist’s flat, angular forms transform the documentary potential of the subject into an agonizing abstraction. Both the painting and the print depict 1963 antisegregation demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama, that led to violent police brutality.64 In the print, Lawrence (1917–2000) highlights the central trope of the painting—the limp, defeated body of a nameless rebel, hauled by two brutish policemen, their batons dangling ominously from their hands. Disembodied faces loom in the upper portion of the sheet, austere against the unrelenting negative space of the background. Deviating from the classicizing naturalism with which Lawrence was certainly familiar, his image transcends the historic particularity of the Birmingham event precisely through the metaphoric language of abstraction.65

Although Lawrence was likely one of the best-known artists in the exhibition, several others had already found widespread recognition in the important 1965 publication Prints by American Negro Artists, a catalogue produced by the Cultural Exchange Center in Los Angeles.66 Work by Joyce Cadoo, Hicks, William E. Smith, and Hartwell Yeargans (all also represented in the Cleveland show) is reproduced in high-quality color plates within the volume. The vast majority of the prints included in the catalogue are non-figural and, like the works in Black Printmakers ’69, convey a diverse array of styles, all of which might be categorized under the auspices of modernism. In the weeks following the opening of Black Printmakers ’69, both the African American Cleveland newspaper Call and Post and the Plain Dealer reported the astounding success of the exhibition and touted the high sales of prints at the show.67 With an adjacent bokari (Swahili for market), Karamu House did not separate the display of art from its purchase. As such, it offered Black artists opportunities for professional advancement beyond the ephemeral fame and recognition promised by the museum world. Helen Borsick, the arts writer at the Plain Dealer, further acknowledged that the exhibition provided a “representative view of the enormous creativity to be found among a hitherto neglected segment of the printmaking population.”68 In view of national racial turmoil, Borsick wrote, “it is difficult to separate purely artistic considerations from thematic content in this exhibition. Let it be said, . . . the show is a dramatic cultural demonstration.”69 Reluctant to characterize the art in the exhibition according to any particular stylistic criteria, Borsick, like other critics of the time, ascribed its significance to the racial “content” of the show.

This dramatic cultural demonstration stood in stark contrast with how prints were displayed and collected in the predominantly white museum spaces in Cleveland at the time. For instance, a press release published in advance of a major retrospective of US printmaking sponsored by the Print Council of America and held in 1962–63 at the CMA recognized that “a veritable renaissance in the medium” was taking place, but the exhibition included only one artist of color.70 Titled America Prints Today! 1962–63, the show displayed fifty-five prints, including canonical examples of modernist abstraction by Josef Albers and Jasper Johns. If a “renaissance” in the medium of print was taking place, the CMA show did not recognize the place of Black artists in that rebirth, perhaps because the curators (wrongly) assumed that Black printmakers worked in an outdated realist style. Black Printmakers ’69 marked a crucial turning point in the history of Black art by emphasizing the role of printmakers, in particular, and by featuring the work of artists whose graphic syntax no longer echoed that of the Harlem Renaissance.

Anticipating pivotal exhibitions like Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (1970), Contemporary Black Artists in America at the Whitney (1971), and Two Centuries of Black American Art at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1979), Black Printmakers ’69 reflected a new attention to the aesthetic merits of art produced by Black artists that looked beyond solely their ability to document the “Black experience.” Further, Black Printmakers ’69 was mounted at Karamu House, where the primary audience was African American or interracial rather than white. As such, Karamu House continued to foster a sense of racial belonging through art that, like better-known community art centers in Chicago and New York, dovetailed with the priorities of the Black Power Movement.71 Future member of AfriCOBRA and Yale professor Michael D. Harris, then a student and patron at Karamu House, notes that the integrationist values of the Harlem Renaissance were supplanted with self-determination and the representation of the Black self.72 Despite its foundation as an interracial theater and arts center, during the 1960s and ’70s Karamu House pivoted to become a more overtly political space in which African American artists and actors alike could assemble to discuss racial inequities.73 Exhibitions like Black Printmakers ’69 therefore worked to cultivate the Black art market described by H. L. Smith and to engender social change.

The success of the exhibition also must have inspired elements of the multiyear Urban Neighborhood Arts Project at Karamu House, which was funded by the National Endowment for the Arts. This program began in 1970 and professionalized young artists as a way of dealing with “life problems caused by racial unrest.”74 Cleveland native Nelson Stevens (1938–1922) began teaching and showing his work at Karamu House during these years, along with other politically motivated artists, including Hal Workman and Curlee Raven Holton. Although he would later be best known as a founding member of AfriCOBRA, Stevens gave regular gallery talks at Karamu House that were a platform for articulating the “emergence of Black art as an expression of our times,” urging Clevelanders to “create positive life images for positive Black folks.”75 Stevens directed African Americans to “unlearn art history, with its lack of appreciation for African and Egyptian art,” and he instead promoted an Afrocentricity that would elevate and encourage Black Americans.76 Nelson’s use of prismatic swatches of acidic color and abstracted stenciling and lettering resulted in a luminous, vibrating form of Black abstraction, despite his often-figural subject matter.77 When combined with the plays of Zora Neal Hurston then being performed on the main stage and the visiting artist talks by Stevens, Bearden, Parks, and others, Karamu House became, according to Holton, “a community center on par with Chicago. If you came to Cleveland in the 1970s, and you were a Black professional, you came to Karamu House. Karamu wasn’t just a showcase, it fostered patronage for and collecting of Black artists.”78 In this way, Karamu artists—and the printmakers, in particular—moved beyond their previous roles as so-called cultural translators for predominantly white audiences.

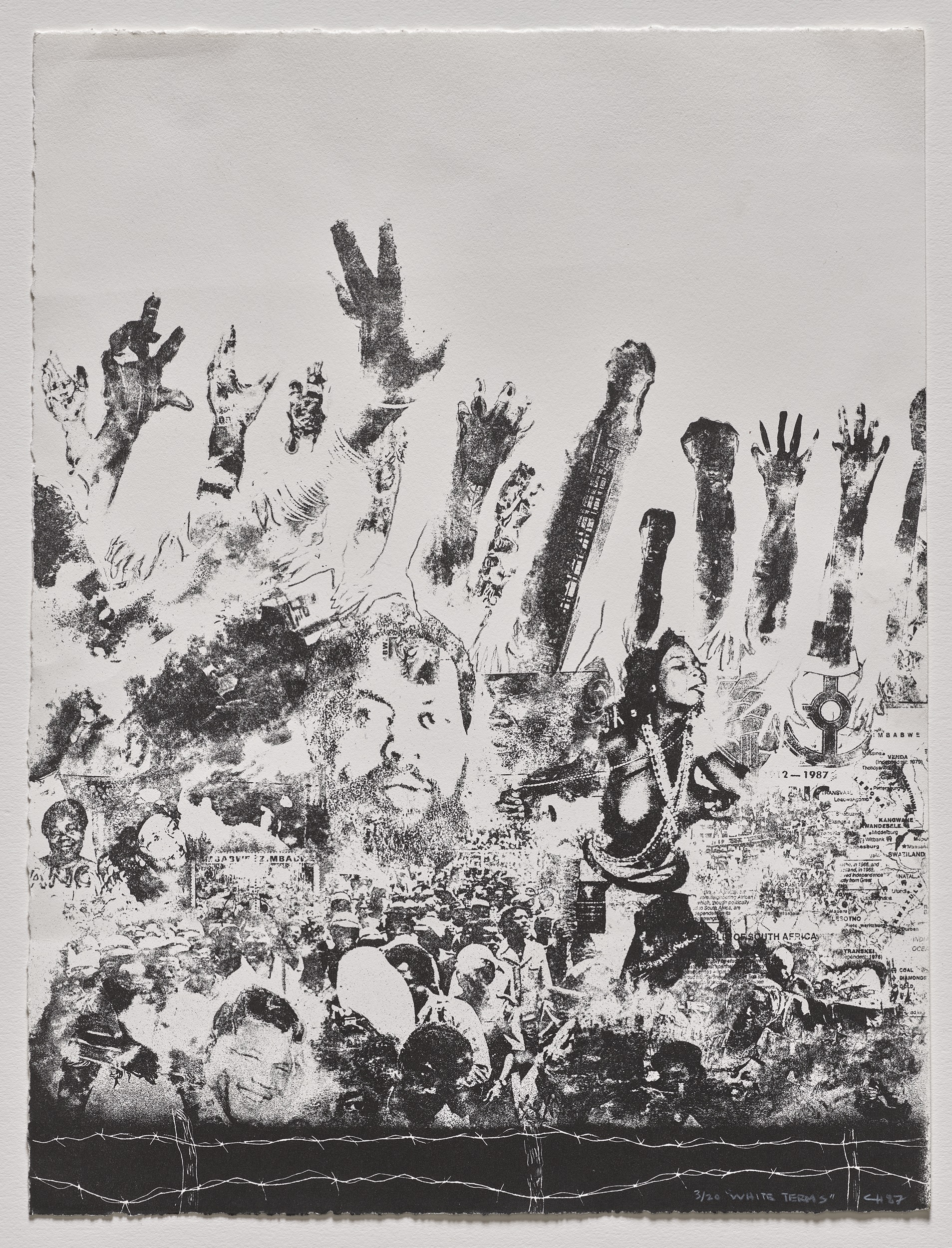

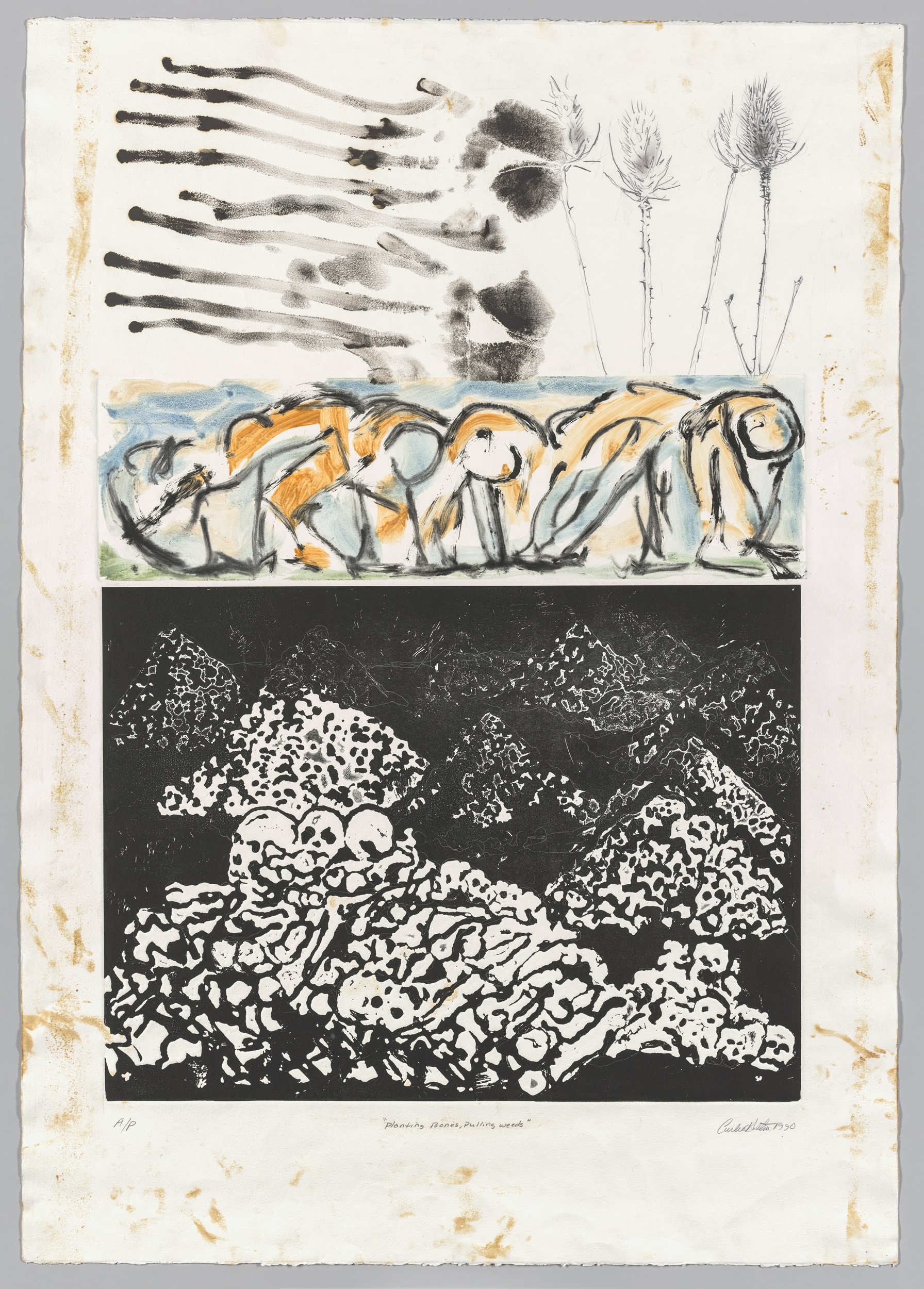

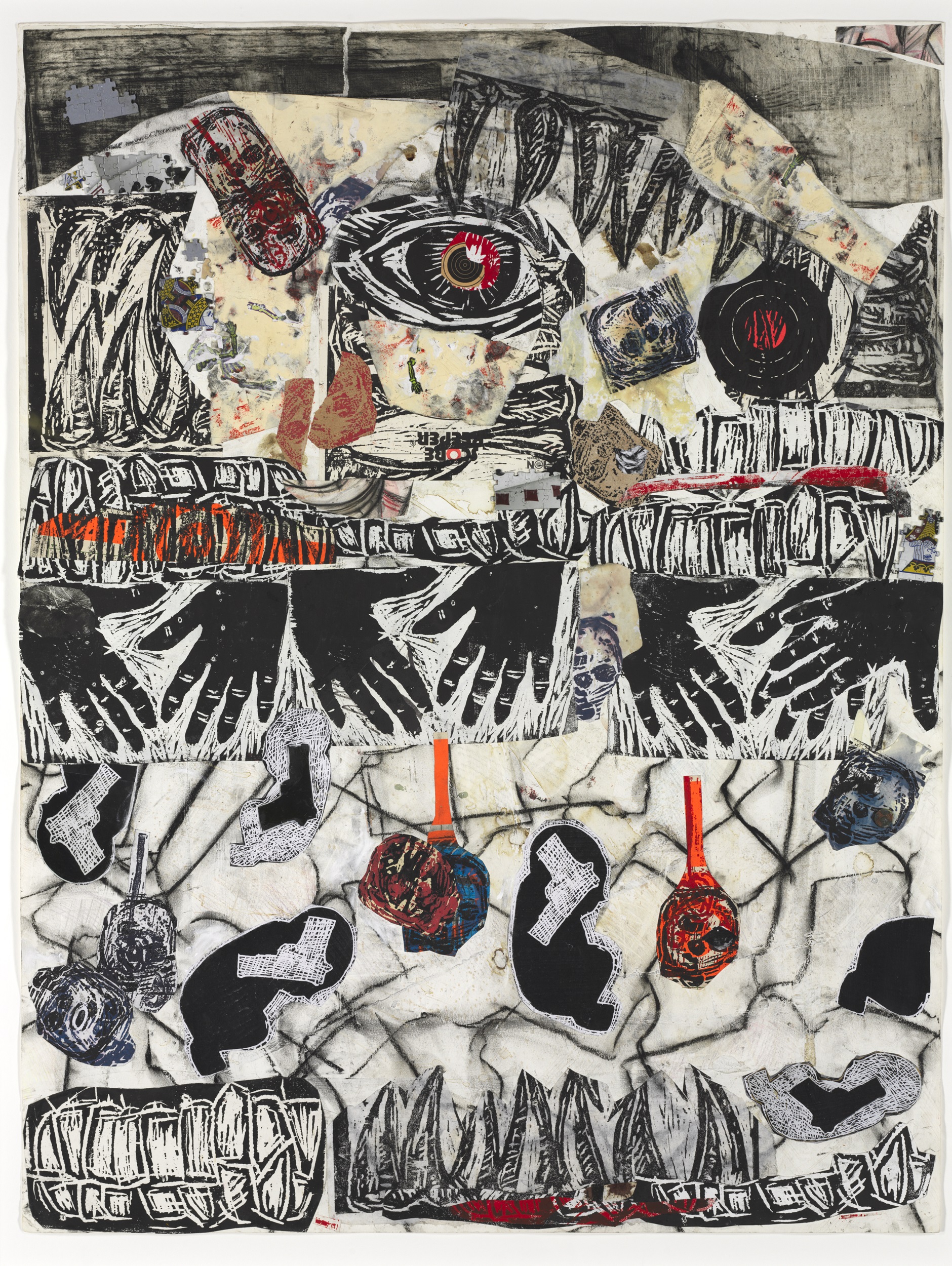

Prints became an indispensable apparatus through which Holton, Stevens, Harris, and members of AfriCOBRA disseminated their “positive images” intended to motivate social action and foster Black power.79 Graphic media, including lithography and screen print (fig. 13), also both associated with commercial arts, have the potential to communicate straightforward messages with bold, appealing designs and were integrally connected with Civil Rights activist art.80 With the establishment of a printmaking department at the Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA) in 1957 and at nearby Kent State University around the same time, there was an organic uptick in artists working in print media in northeastern Ohio over the next twenty years. As a part-time undergraduate student at CIA, Holton, who would go on to found the prestigious Experimental Printmaking Institute at Lafayette College, made his first print, a lithograph titled White Terms (fig. 14), while attending a meeting of the local chapter of the Africa National Convention (ANC). Attendees made prints to benefit ANC efforts to end apartheid in South Africa. A pastiche of Xerox transfers, the print assembles a bustling crowd of figures—some identifiable as Holton himself, his wife, and the Cleveland poet Bob Woods, while others are unrecognizable—their arms raised in protest. Dislodged from the masses below, these disembodied arms signify for Holton “Blacks reaching for freedom and whites pushing them down.”81 Etched with an X-acto knife into the lithographic stone, a menacing barbed-wire fence lines the bottom of the print. This sharp white line barricades both the densely packed protestors and the metaphorical space of Black activism. Holton was astounded by the mechanical pressure of the press and by the comparative tolerance of the inked paper; printmaking became the perfect metaphor to convey Holton’s political and artistic philosophies, articulating his figural and abstracted visions of race, violence, and beauty in the bifurcated United States (fig. 15).82

Holton’s prints, like those by Stevens and members of AfriCOBRA, were politically explicit and reflected growing racial tensions in Cleveland. During the 1960s, Muhammad Ali, Amiri Baraka, and others stopped at Karamu House on their visits to Cleveland as the center became a politicized space and Cleveland a “hotbed of Black Nationalism” (fig. 16).83 The 1966 riots in the historically African American neighborhood of Hough surfaced years of festering racial antagonism that, in a 1967 issue of the Saturday Evening Post, led John Skow to portray the entire city as “the mistake on the lake.”84 Against the backdrop of a burning city, Carl Stokes campaigned in 1967 with the slogan “I Believe in Cleveland,” calling for a “renaissance, a resurgence of faith in ourselves, a renewal of spirit and morale as well as a renewal of buildings and other physical facilities.” Stokes assured voters that his campaign had “no room for unclean peddlers of bigotry and hatred.”85 With his historic election, Stokes initiated a major urban revitalization strategy under the banner Cleveland: NOW! Plans to repair, beautify, and literally to lighten the city with thousands of added streetlights were coupled with efforts to add green city spaces in historically Black neighborhoods and to provide affordable housing for underrepresented communities.86

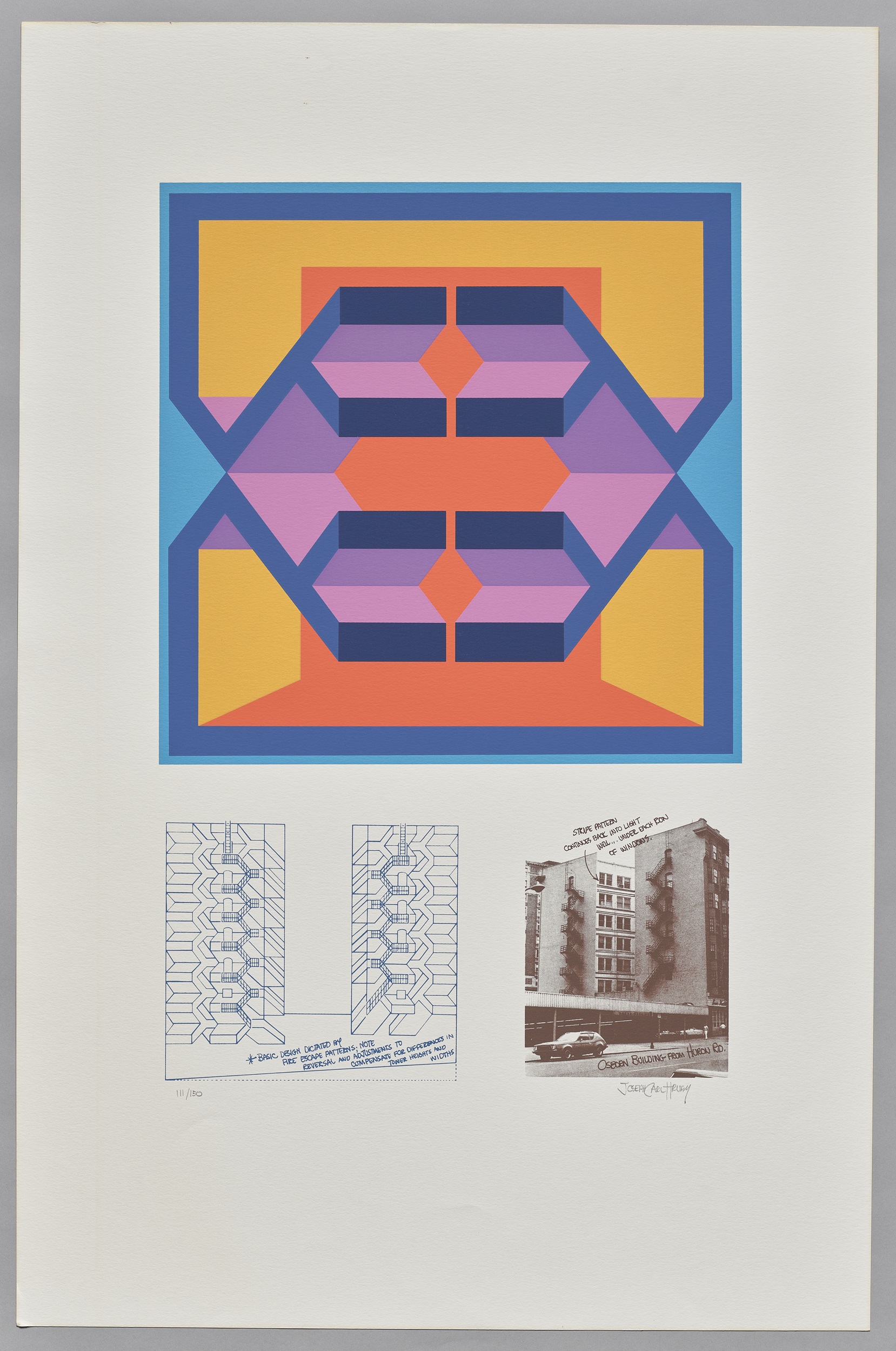

Attempts to revitalize Cleveland’s Black neighborhoods resulted in projects built around cultural production that often left Black artists to the side. The 1973–74 National Endowment for the Arts–funded project City Canvases was, for instance, a systematic effort to decorate underresourced neighborhoods with murals by exclusively white artists, accompanied by a limited-edition set of screen prints now owned by the CMA (fig. 17). The murals are no longer extant, but the prints shed light on the ways that art was appropriated as a tool for urban renewal even, as James Baldwin rightly pointed out in 1963, if that renewal came at the cost of “negro removal.”87 In 1977, the program was expanded, initiating a phase of public art making in Cleveland in which “community needs” were ostensibly integrated with efforts to revitalize ravaged neighborhoods.88 And yet, African American artists were still often marginalized from these processes of urban reclamation; instead it was in the medium of print that Black artists made important moves to cultivate a clientele of their own.

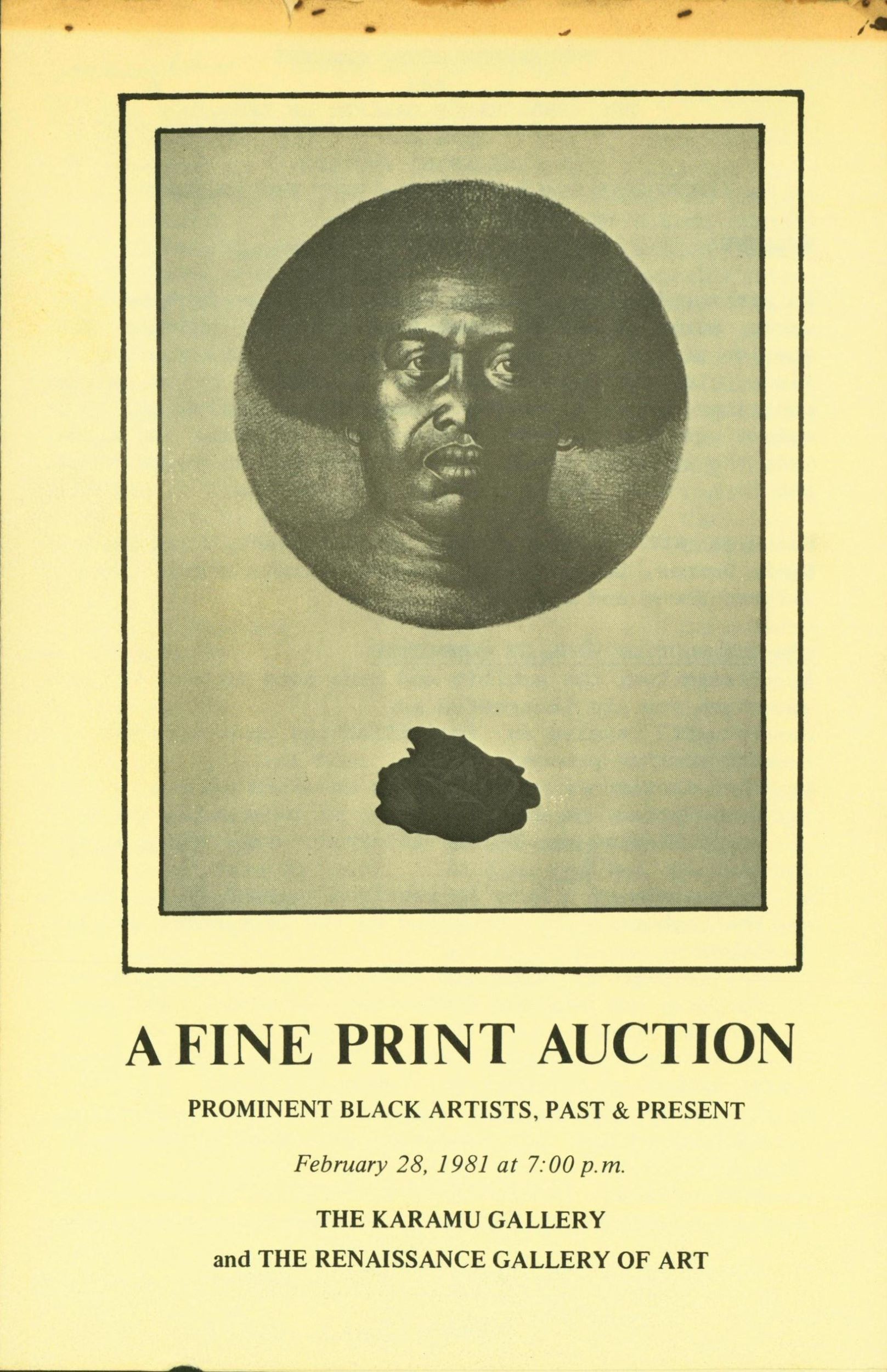

Like other major US cities, Cleveland’s urban development history is mired in discriminatory real estate practices that worked to segregate African Americans and to restrict their upward mobility. But by the 1960s, the integration of affluent inner-ring suburbs, like Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights, was underway.89 With a rising Black upper-middle class with disposable income to spend, Holton and others moved to fill the art-collecting demand first fostered by Karamu Artists Inc.90 Holton began curating traveling print sales at the homes of prominent collectors; he later brought prints to the after-parties of Black Professional Association meetings, effectively fostering a Black art market in Cleveland at a time when the predominantly white cultural institutions of the city were still unofficially segregated. With Karamu House support, the Malcolm Brown Gallery and the Renaissance Gallery opened in Shaker Heights and Cleveland Heights in 1980 and 1981, respectively.

Both galleries were established in what might be considered neighborhoods at the “urban periphery” and therefore contributed to shaping city spaces that were the loci of “Black middle-class social, economic, and political life.”91 Several historically significant Black-owned galleries had opened in New York and Washington, DC, during the 1940s and ’50s, and the 1960s and ’70s witnessed the addition of prestigious Black-owned galleries in Los Angeles.92 These Black-owned arts spaces marked a distinct turn away from the integrationist philosophy that had previously governed attempts to penetrate preexisting arts institutions.93 By the 1960s, Black businesspeople instead worked toward the creation of autonomous spaces of cultural consumption that arguably helped to construct Black middle- and upper-middle class identities.94 The ownership of Black art by Black patrons also worked against the “historic relational or spatial strategies that posited (white) subjectivity against (black) objectification, with whites as the owners and blacks as the owned,” as Craig Wilkins discusses.95 Much like Black homeownership, a well-documented marker of middle-class status, the possession of Black art by Black people likely signaled a desire to respond to and rectify legacies of Black marginality in cities like Cleveland.

With Karamu House acting as a sponsor, the Renaissance and Malcolm Brown galleries continued to foreground the work of nationally recognized Black printmakers, such as Charles White, Elizabeth Catlett, Romare Bearden, Ernie Barnes, and Leroy Foster.96 The establishment of a Black art scene in Cleveland was cemented when both Catlett and Bearden held exhibitions at the Malcolm Brown Gallery within just two years of its opening. Catlett arrived to a packed opening for her show in 1981, and the celebrated printmaker and sculptor led a printmaking workshop at the CMA while she was in town. Bearden’s first Midwestern show was held in 1982; already a giant in the art world, Bearden declared the event a call to responsibility for Black artists. “I think what is happening now, and why I am showing here, is that you have to respect first the Black entrepreneur—the Black gallery owner, and also the collector, after all an artist does paint for someone,” he told a Call and Post reporter. “Black gallery owners should be respected just as their white counterparts are.”97 Although geographically and institutionally distinct from Karamu House, both the Renaissance and Malcolm Brown galleries owed their foundation to it, a metaphorical debt that they paid back in print auctions to sponsor the community center (fig. 18).98

Arthur and Murtis Taylor were major clients of both galleries. The Taylors were leaders in the African American community, and as director of the Mount Pleasant Community Center, Murtis was also a force for interracial sociability and tolerance.99 Michael White, then city councilman and later mayor of Cleveland; George Lawrence Forbes, a lawyer and president of the city council; Sharon Williams, the director of public affairs for a local television station; and Cosmo Morgan, the son of the late Cleveland inventor Garret Morgan, were among Holton’s other important patrons. Just as Karamu House exhibitions and sales functioned as vital social functions, so too did events at the Renaissance Gallery. Regularly described in the pages of the Call and Post, Holton and his wife, gallery director Glee Ivory, hosted openings for crowds of more than two hundred, where guests “sipped champagne while they moved around the gallery, studying the works and mingling with other art lovers who continued to express appreciation for the fact that the gallery was opened to primarily promote black art.”100 Many of these events also served as fundraisers to support community projects, such as the restoration of the historic home of Garret Morgan, inventor of the stoplight and gas mask.101 Karamu House featured programming related to the exhibitions at the Malcolm Brown and Renaissance galleries, encouraging an active dialogue about the role of “black artists yesterday, today, and tomorrow.”102 The making, displaying, and collecting of Black art in this context indexed the ascent of Black artists in a struggling Midwestern city where Black power was on the rise.

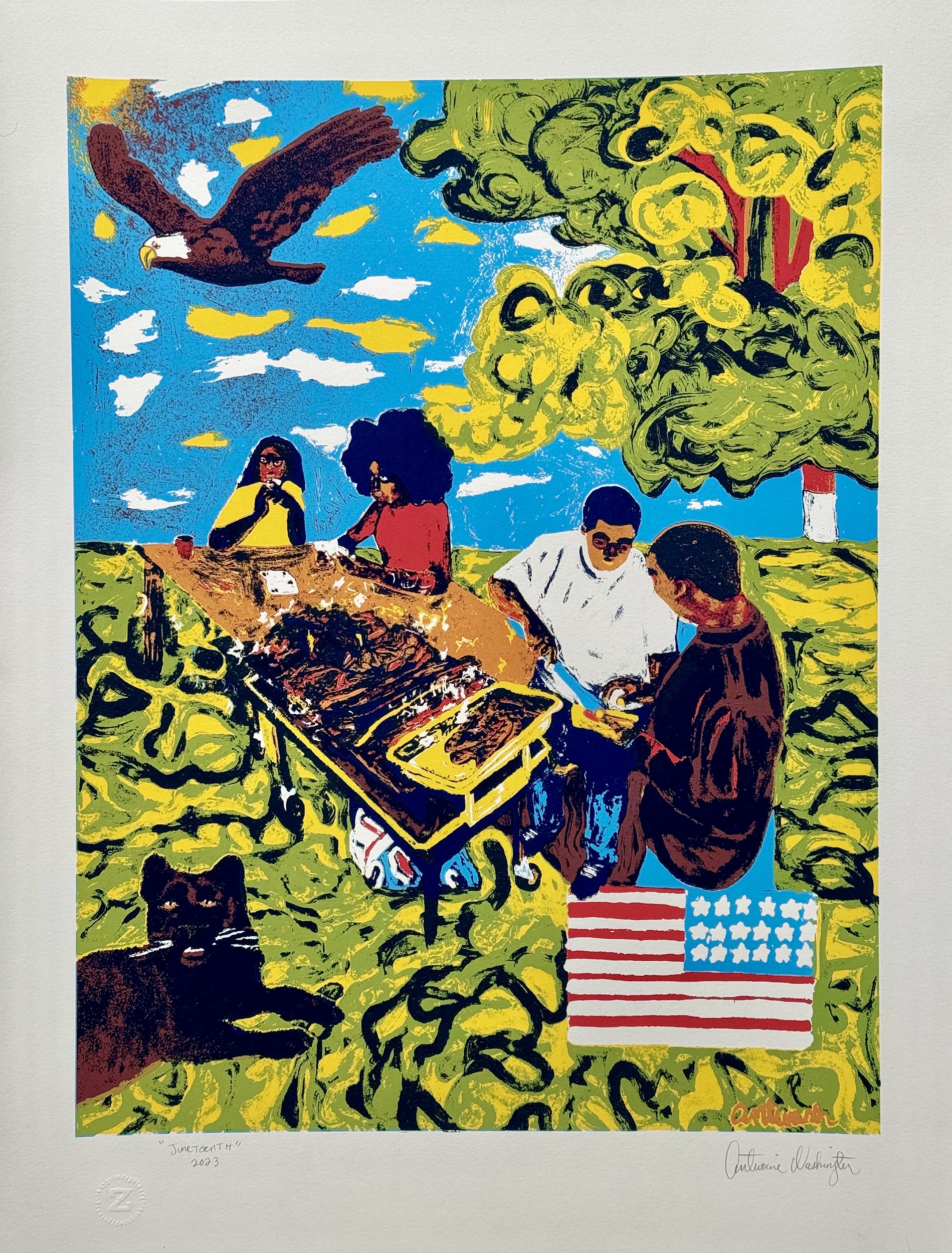

The Malcolm Brown Gallery and the Renaissance Gallery closed in the early 2000s, but other Cleveland art spaces have risen to meet the demand first cultivated by Karamu House in the 1930s. For instance, Gallery 2602, founded by curators Deidre McPherson and Thea Spittle, is a converted Cleveland Heights house that features the work of BIPOC artists and creatives. A recent exhibition of paintings by Cleveland artist Antwoine Washington was accompanied by the sale of a limited-edition screen print, Juneteenth, made in consultation with Cleveland’s only collaborative, open-access printmaking shop, Zygote Press (fig. 19). Displayed among the domestic trappings of a home interior, Washington’s paintings and their exhibition in this hybrid space evoke “vernacular curatorial practices” long associated with the display of art in Black family homes.103 As La Tanya S. Autry rightly points out, such an exhibition “demonstrates that patrons can find ways to support arts and culture initiatives grounded in caring about Black people. . . . Counter-hegemonic projects [like Gallery 2602] show that other trajectories for making and funding aesthetic experiences exist.”104 In Cleveland, such trajectories arguably began with Karamu House.

Like the far better-known Southside Community Art Center in Chicago, Karamu House remains a critical node in a constellation of Black Midwestern artistic centers with rich print traditions. Contemporary Cleveland artists Amanda King, Dexter Davis (b. 1965), and Darius Steward have all expanded their artistic training and exhibition practices by making and showing their printed work at Karamu House (fig. 20). More important, however, Karamu House has played a decisive part in shaping Black cultural capital in the city, a point that is reflected in the recent formation of FRONT International, a triennial for contemporary art that explicitly considers the role of artists of color at the intersections of social justice and art.

FRONT’s 2022 exhibition Oh, Gods of Dust and Rainbows summons verses from Langston Hughes’s 1957 poem “Two Somewhat Different Epigrams”:

I. Oh, God of dust and rainbows, help us see

That without dust the rainbow would not be.

II. I look with awe upon the human race

And God, Who sometimes spits right in its face.105

FRONT artistic director Prem Krishnamurthy suggests that visitors meditate on the inseparability of joy and suffering encoded in the poem. Spanning thirty different installation sites and featuring the work of one hundred artists, FRONT’s 2022 exhibition was monumental. Hughes’s poem was repeatedly marshaled as a fitting backdrop against which to stage humanistic dialogues about art, race, and empathy. Invoked as evidence of the poet’s early career in Cleveland, Hughes’s inscriptions remind a new generation of viewers and artists alike of Karamu House’s lasting role in the production of rust-belt culture.

By looking to the work of Karamu Artists Inc. of the WPA era, by recovering the archival evidence of its art program during the 1960s and ’70s, and by interrogating its role in Black art making and collecting in the Midwest, we see how prints are anything but peripheral to the art histories we tell. The story of printmaking at Karamu House, of Karamu Artists Inc., and of the community center at the heart of the Black Arts Movement and collecting in Cleveland is, however, at risk of being forgotten, repeatedly upstaged by its better-known peers in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Amplifying the role of Black arts in Cleveland means rewriting an art history in which Black artists have been relegated to a distant WPA-era past and only recognized in a very limited geography. When we circumscribe Black art making to the federally sponsored, pleasantly democratizing moment of the 1940s, we successfully avoid acknowledging the deeply entrenched racism that plagued the professionalization of Black artists as artists throughout the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, and ultimately to the present day. Rather than understand the end of the WPA-FAP as the foreclosure of fine art printmaking and the apotheosis of Black art in Cleveland, we can now recognize it as the crucial incubus for an enduring visual art tradition and thriving Black art market nurtured by Karamu House in an often-disregarded Midwestern city.106

Cite this article: Erin Benay, “Peripheral Prints: Karamu House and the Rise of African American Art in the Midwest,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18832.

Notes

My profound gratitude is extended to Tony Sias, current director of Karamu House; Kenneth Snipes, former director of Karamu House; and Curlee Raven Holton, without whom this research would not have been possible. I am also indebted to the anonymous reviewers of this essay, whose comments and feedback were invaluable to shaping my thinking, and to Britany Salsbury, curator of prints and drawings at the Cleveland Museum of Art, for her infinite generosity. Karamu House will be the subject of a major exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art in March 2025 (co-curated by Salsbury and myself, with contributions by Jacqueline Francis and Richard Powell).

- Philanthropic print clubs were later established at most major US art museums; see Theresa Moir Engelbrecht, “Inter-Collected: The Shared History of the Print Club and Museum Collection,” Art in Print 7 (2017): 30–33. ↵

- As in other US cities, Cleveland’s African American population surged at this time: between 1910 and 1920, the Black population increased almost fourfold, from 8,763 to more than 35,000. See Virginia Dawson, “Protection from Undesirable Neighbors: The Use of Deed Restrictions in Shaker Heights, Ohio,” Journal of Planning History 21 (2018): 1. Most of this population was confined to the southeast corner of the city in Cedar-Central, where Karamu House was first located. See John Selby, Beyond Civil Rights: Karamu’s 50 Years of Interracial Understanding, Achieved through the Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts (Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1966), 11; Leslie King-Hammond, “Black Printmakers and the WPA,” in Alone in the Crowd: Prints of the 1930s–40s by Afro-American Artists from the Collection of Reba and Dave Williams, ed. Reba Williams and Dave Williams (New York: American Federation of the Arts, 1993), 15. ↵

- Langston Hughes made a number of linocuts at Karamu House; several of these will appear in the forthcoming exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art and are loans from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. See, for example, Windshield in the Rain (JWJMSS 26) and Carnival: Havana (JWJMSS 26), both of which have cover sheets written in Hughes’s hand indicating that they were “made at Karamu House.” ↵

- James Porter, Modern Negro Art (New York: Arno, 1943), 159–66. ↵

- Mark Cole’s important essay “‘I, Too, Am America’: Karamu House and African-American Artists in Cleveland” remains the only substantive art-historical treatment of Karamu Artists Inc.; it was published in the exhibition catalogue Transformations in Cleveland Art, 1796–1946, ed. William Robinson (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1996), 148–75. Karamu Artists Inc. is absent, for instance, from Caroline Goeser’s fundamental text Picturing the New Negro: Harlem Renaissance Print Culture and Modern Black Identity (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2007); and from Allan Edmunds, “The Printed Image: Process and Influences in African American Art,” in The Routledge Companion to African American Art History, ed. Eddie Chambers (London: Routledge, 2020), 395–405. Nor are they recorded in many histories of WPA-FAP art making, such as John Franklin White, Art in Action: American Art Centers and the New Deal (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1987). ↵

- Elizabeth Seaton makes this point with regard to “mainstream” American collectors in Art for Every Home: Associated American Artists, 1934–2000, ed. Elizabeth G. Seaton, Jane Myers, and Gail Windisch (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015), 89–110. ↵

- Lowery Stokes Sims, “African-American Artists as Printmakers,” in Williams and Williams, Alone in the Crowd, 1–6. ↵

- The literature about art of the WPA era is extensive; on African Americans and the WPA-FAP, see, for example, Mary Ann Calo, “Expansion and Redirection: African Americans and the New Deal Federal Arts Projects,” Archives of American Art Journal 55 (2016): 80–91; Leslie King-Hammond, “Black Printmakers and the WPA,” in Williams and Williams, Alone in the Crowd, 10–20. On the WPA and the FAP more generally, see A. Joan Saab, For the Millions: American Art and Culture between the Wars (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004); Victoria Grieve, The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009); Isadora Anderson Helfgott, Framing the Audience: Art and the Politics of Culture in the United States, 1929–1945 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2015). It is telling that the magisterial exhibition and catalogue Art for Every Home describes at great length the democratization of art by the Associated American Artists but does not call attention to role of race in that process. ↵

- See Mary Ann Calo, “A Community Art Center for Harlem: The Cultural Politics of ‘Negro Art’ Initiatives in the Early 20th Century,” Prospects: An Annual of American Cultural Studies 29 (2005): 155–83. ↵

- Selby, Beyond Civil Rights, 122. ↵

- In the floorplans, financial documents for art classes, and descriptive passages of text found throughout the Karamu House archives, there is no mention of a printing press or expenses related to the upkeep of such a press during the 1930s and ’40s. Instead, portfolios of children’s relief prints and Karamu House artist W. E. Smith’s descriptions of working practices at Karamu suggest that linoleum and carving tools were available for use at the center. See MS 4606, boxes 3, 21, 22, 24, 28; and MS 4737, box 17, folder 244, Jelliffe Papers, all at Karamu House Records, Western Reserve Historical Society, hereafter WRHS. ↵

- Cole, “I, Too, Am America,” 151–54. ↵

- William E. Smith, The Printmaker: From Umbrella Stave to Brush and Easel (exhibition pamphlet), compiled by W. E. Smith and M. W. Johnson, p. 4, Clippings File, Cleveland Museum of Art. ↵

- Linoleum was invented and patented by Frederick Walton in 1860 and was brought to the United States around the turn of the century. Between the 1920s and ’40s, US linoleum production was dominated by only three manufacturers, two in Pennsylvania and one in New York. See Pamela H. Simpson, “Linoleum and Lincrusta: The Democratic Coverings for Floors and Walls,” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 7 (1997): 281–92. ↵

- Elizabeth Seaton, “Federal Prints and Democratic Culture: The Graphic Arts Division of the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project, 1935–1943” (PhD diss., Northwestern University, 2000), 93, 222–77. There were only nineteen African American artists employed in WPA-FAP print shops, and most were concentrated in Cleveland, New York, and Philadelphia. ↵

- For the history of the WPA-FAP Graphic Arts Project in Cleveland, see Sabine Kretzschmar, “Art for Everyone: The Cleveland Print Makers and the WPA,” in Robinson, Transformations in Cleveland Art, 182–83. ↵

- Although a full interracial history of print in Cleveland has yet to be written, Kubinyi’s role and that of Cleveland printmakers has been treated in part by Kretzschmar, “Art for Everyone,” 177–97. ↵

- Seaton, “Federal Prints and Democratic Culture,” 203. ↵

- The original founding members of Karamu Artists Inc. were Elmer William Brown, Fred Carlo, William E. Smith, Charles Sallée, Thomas Usher, Hughie Lee Smith, and Zell Ingram (MS 4606, box 21, folder 363, Karamu House Records, WRHS). ↵

- Karamu Artists Inc. Constitution and By-Laws, 1941, n.p., MS 4606, box 21, folder 363, Karamu House Records, WRHS. ↵

- Southside Community Art Center (SCAC) is one of the best known and frequently cited Black community arts centers in the country; much of the literature about SCAC treats particular aspects of the center’s long history. See, for example, Erik Gellman, The Black Chicago Renaissance (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012); Mary Ann Cain, South Side Venus: The Legacy of Margaret Burroughs (Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 2018); and, for a broader overview of the SCAC in relationship to Chicago’s activist art scene, Rebecca Zorach, Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965–75 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019). ↵

- Karamu Artists Inc. Constitution and By-Laws. ↵

- Grace V. Kelly, “Six Young Artists Launch New Karamu Organization to Aid Fellow Craftsmen,” Plain Dealer, July 7, 1940, 51. Western Reserve University is now Case Western Reserve University. ↵

- Karamu Artists Inc. Constitution and By-Laws. ↵

- “Exhibition of Karamu House Work of Graphic Artists,” checklist, Curator’s Files, Cleveland Museum of Art. ↵

- These descriptive labels are archived by the Cleveland Museum of Art and by the Western Reserve Historical Society (MS 4606, box 21, folder 361). ↵

- Descriptive labels, WRHS (MS 4606, box 21, folder 361). Elmer Brown’s own label differs in the spelling of “Old Peckerwood” from the title given to the print by Cleveland Museum of Art, Ol’ Peckerwood. ↵

- Flight wrote and published extensively about the qualities of linocuts during his lifetime; see, for example, The Art and Craft of Lino Cutting and Printing (London: B. T. Batsford, 1934), 1048. Flight’s contributions to the history of art are discussed by Gordon Samuel, The Cutting Edge of Modernity: Linocuts of the Grosvenor School (London: Lund Humphries, 2002). ↵

- I have argued this elsewhere: Erin Benay, “Casta State of Mind: Michael Menchaca and the Graphic Revolution of Caste,” Art Journal 81 (2022): 55–74. ↵

- William Lieberman, Matisse: Fifty Years of His Graphic Art (New York: George Braziller, 1956), 13–14. ↵

- Several of these playbills will appear in the Karamu House exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art, March 2025. Karamu House playbills can be found in several archives: MS 4606, box 13, folder 238; box 28, folder 497; MS 4737, box 9, folder 157, Jelliffe Papers; and ArtNEO scrapbook, all at Karamu House Records, WRHS. Ingram illustrated the first-edition cover of Langston Hughes, Dear Lovely Death (Armenia, NY: Torutbeck, 1931), Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, JWJ Zan H874 931d 1. ↵

- Stephen Coppel, Linocuts of the Machine Age: Claude Flight and the Grosvenor School (Hampshire: Aldershot, 1995), 7. ↵

- As Bridget Cooks proves, such curatorial approaches tend to emphasize the anthropological “reality” of Black artists and subjects rather than to frame the work of Black artists in aesthetic terms; in Exhibiting Blackness (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011), 1–5. The prints themselves were also anything but neutral documents; see Helen Langa, “Protesting Societal Injustice: Antiracism in 1930s Prints,” in Radical Art: Printmaking and the Left in 1930s New York (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 128–66. ↵

- Seaton, Myers, and Windisch, Art for Every Home, 10. ↵

- Seaton, Myers, and Windisch, Art for Every Home, 10. ↵

- Exhibit by Karamu Artists (New York: Associated American Artists, 1942). ↵

- Exhibit by Karamu Artists. ↵

- Cooks, Exhibiting Blackness, 42. As Cooks demonstrates, early exhibitions like Exhibition of the Sculpture of William Edmondson at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (1937), and Contemporary Negro Art at the Baltimore Museum of Art (1939) were less about the aesthetic merits of the art and artists and much more about the role of art in smoothing race relations. ↵

- Exhibit by Karamu Artists. ↵

- Mary Ann Calo, Distinction and Denial: Race, Nation, and the Critical Construction of the African American Artist, 1920–40 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007), 18. ↵

- James Edward Smethurst, The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 25. ↵

- Porter, Modern Negro Art, 159. ↵

- Cooks, Exhibiting Blackness, 18. ↵

- Cole, “I, Too, Am America,” 146. ↵

- Although the style employed by Black artists of the WPA era was, at the time, often denigrated as an example of simplistic “folk” aesthetics, Kellie Jones (among others) proves its place in a history of abstraction: Energy/Experimentation: Black Artists and Abstraction, 1964–80 (New York: Studio Museum in Harlem, 2006). ↵

- David C. Driskell, Two Centuries of Black American Art (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art with Random House, 1976), 56. ↵

- Porter, Modern Negro Art, 133. ↵

- See Jacqueline Francis, Making Race: Modernism and “Racial Art” in America (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012). ↵

- Calo, Distinction and Denial, 124. ↵

- The topic of Black art and abstraction has been the subject of extensive study; recent and important contributions include Jones, Energy/Experimentation; Phillip Brian Harper, Abstractionist Aesthetics: Artistic Form and Social Critique in African American Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2015); and, for a concise historiographic essay, Sarah Lewis, “African American Abstraction,” in Chambers, ed., Routledge Companion to African American Art History, 159–73, with bibliography. On dichotomies of seeing Black art in the museum context, see, for example, Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007); Richard Powell, Black Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2021). ↵

- Lowery Stokes Sims, Challenge of the Modern: African American Artists, 1925–1945 (New York: Studio Museum, Harlem, 2003), 1:13–14. ↵

- Kellie Jones, “It’s Not Enough to Say ‘Black is Beautiful’: Abstraction at the Whitney, 1969–1974,” in EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 408. ↵

- Exhibition checklists, boxes 1–3, Records of the Extensions Department, Ingalls Library, Cleveland Museum of Art. ↵

- Karamu House, Hugh Calkins, Karamu Board president, “The Karamu Exhibits—Some Observations and Evaluations,” written to then-director of the CMA Sherman Lee, 1960, n.p, box 24, folder 430, WRHS. Karamu House also had its own small collection of African objects that derived from artist Paul Travis’s 1927–28 collecting trip to Africa, which was funded in part by the CMA. ↵

- John Ott, “Hale Woodruff’s Antiprimitivist History of Abstract Art,” Art Bulletin 100, no. 1 (2018): 124–45. ↵

- Smethurst, Black Arts Movement, 17. ↵

- For these two models, see Susan Tallman, The Contemporary Print: From Pre-Pop to Postmodern (London: Thames and Hudson, 1996). ↵

- Curlee Raven Holton, interview with the author, July 1, 2023. ↵

- Hughie Lee Smith, “The Negro Artist in America Today,” Negro History Bulletin 27, no. 5. (February 1964): 111–12. ↵

- Curlee Raven Holton, interview with author, July 1, 2023. ↵

- “Karamu Festival to be Focal Point for Arts,” Call and Post, October 16, 1965, 12B. ↵

- Kenneth Snipes to Rost Warden, managing editor at Fine Arts Incorporated, MS 4606, box 22, folder 386, Karamu House Records, WRHS. ↵

- Press release for the exhibition, MS 4606, box 22, folder 387, Karamu House Records, WRHS. ↵

- Peter T. Nesbett, “Introduction: Jacob Lawrence: From Paintings to Prints,” in Jacob Lawrence: The Complete Prints (1963–2000); A Catalogue Raisonné, 2nd ed. (Seattle: Francis Seders Gallery, 2001), 9. ↵

- Although a full history of abstraction in Black Art and art historiography in the United States lies outside the scope of this article, it undergirds the transformations in making and collecting that are highlighted here. See, for example, Sims, Challenge of the Modern, 13–14. ↵

- T. V. Roelof-Lanner, ed., Prints by American Negro Artists (Los Angeles: Cultural Exchange Center, 1965). ↵

- Helen Borsick, “Impressive Imprints,” Plain Dealer, May 11, 1969, 16E; Lauretta White, “Karamu Presents Black Printmakers,” Call and Post, May 24, 1969, 2A. ↵

- Borsick, “Impressive Imprints.” ↵

- Borsick, “Impressive Imprints.” ↵

- American Prints Today! 1962–63, Exhibition/history, Cleveland Museum of Art archives. ↵

- Although Karamu House has been almost entirely excluded from these discussions, African American community art centers in other urban centers have been the subject of extensive scholarly analysis. See, for example, Elizabeth Schroeder Schlabach, Along the Streets of Bronzeville: Black Chicago’s Literary Landscape (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 25–49; Smethurst, Black Arts Movement, 179–246. ↵

- Michael D. Harris, interview, 2010, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, https://www.si.edu/es/object/archives/sova-aaa-africobr. ↵

- Holton, interview with author, July 1, 2023. ↵

- Urban Neighborhood Arts Project Proposal, 1969, MS 4606, box 3, folder 61, Karamu House Records, WRHS. ↵

- Borsick, “Brightly Black,” Plain Dealer, January 23, 1972. On the aesthetic philosophy of AfriCOBRA, see Kristn L. Ellsworth, “Africobra and the Negotiation of Visual Afrocentrisms,” Civilisations 58 (2009): 21–38. ↵

- Ellsworth, “Africobra and the Negotiation of Visual Afrocentrisms,” 25. ↵

- Margo Natalie Crawford, “When Black Experimentalism Became Black Power: The Black Arts Movement and Its Legacies,” in Chambers, ed., Routledge Companion to African American Art History, 104–15. ↵

- Holton, telephone interview with the author, July 18, 2022. ↵

- Rebecca Zorach, “‘Dig the Diversity in Unity:’ AfricCOBRA’s Black Family,” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context, and Enquiry 28 (2011): 108. ↵

- E. Carmen Ramos, “Printing and Collecting the Revolution: The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now,” in ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, ed. E. Carmen Ramos (Washington, DC: Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2020), 25. ↵

- Holton, email correspondence with the author, July 18, 2023. ↵

- Holton, interview with author, July 1, 2023. ↵

- On the political and racial climate of Cleveland under Stokes, see Leonard N. Moore, Carl B. Stokes and the Rise of Black Political Power (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2003). ↵

- John Skow, “The Question in the Ghetto: Can Cleveland Escape Burning?” Saturday Evening Post, July 29, 1967. ↵

- Stokes for Mayor Committee advertisement, Plain Dealer, July 28, 1967. ↵

- For a concise history of Stokes’s mayoral tenure, see J. Mark Souther, Believing in Cleveland: Managing Decline in the “Best Location in the Nation” (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017), 93–120. ↵

- James Baldwin, “A Conversation with James Baldwin,” interview, June 24, 1963, American Archive of Public Broadcasting, https://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip_15-0v89g5gf5r. ↵