Philly Necrofutures: Digital Curation to Counter the Under-Resourcing of African Collections at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

PDF: Whitham Sanchez & Smith, Philly Necrofutures

The exhibition Philly Necrofutures is a collaboration between Synatra Smith and Hilary Whitham Sánchez to address the lacuna in public and scholarly knowledge around the western and central African artworks held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA).1 Combining art-historical research with a mapping visualization seen through an Afrofuturist lens, we have created an interactive digital exhibition that directly grapples with colonial archives to center African makers, reaching scholarly and general audiences both locally and internationally.

Departing from popular notions of a “Black science fictional aesthetic,” we employ a conceptual framework rooted in what cultural critic Mark Dery terms “Afrofuturism,” which I (Smith) define as a reimagining of time and space through fantasy or technology in order to speculate about the future.2 Our approach is also aligned with Africanfuturism, defined by American Studies scholar Lidia Kniaź as “more future-oriented, focused on implementations of real technologies to improve the economic and political shape of tomorrow’s Africa rather than reassessing the past and contemplating contemporary American issues.”3 We acknowledge that we are not directly engaging with individuals on the continent in our work on this project, but we do aim to use our positions as individuals connected to the PMA through term-limited fellowships to advocate for an antiracist approach to art-historical praxis that decenters Eurocentric narratives in favor of underscoring the Africanness of each sculpture. Africanfuturism and Afrofuturism share some commonalities as speculative practices for African and African-descended people, but the former can operate as a critique of the latter, which often promotes a romanticized version of the African continent above the lived and historical experiences of people who exist and have existed in that geographical region.

Our work uses digital tools (namely technology) to represent and interpret works from the continent (that is, physical space) through a virtual story map, a visualization website that blends narrative and geographic data, enabling us to both reconstruct and problematize the routes through which a group of sculptures arrived in Philadelphia. By emphasizing their meanings within their communities of origin on the African continent, we subvert the Eurocentric colonial timescales that equate their creation with their arrival in the West and circumvent the PMA’s problematic database management system. Furthermore, digital tools enable us to bring local undergraduate students into the process of stewarding these artworks.4 Philly Necrofutures demonstrates the way complementary sets of expertise can disrupt the harmful Eurocentric/Euro-Americentric, patriarchal paradigms of the galleries, libraries, archives, and museum industry (which we will jointly refer to with the acronym GLAM) and their attendant lack of support for scholarship on African and diasporic arts by scholars of color, instead centering antiracist collaborative initiatives.

Historical and Intellectual Context

Long-standing international discussions about the ethics of collecting and presenting African objects during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries garnered significant attention from the general public in 2018 with the release of The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Towards a Relational Ethics. This study was commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron and carried out by provenance research expert Bénédicte Savoy and the economist and theoretician Felwine Sarr. Savoy and Sarr’s assessment of France’s collections determined that nearly all of the African artworks held in national repositories had been acquired through illegal or unethical means and should be eligible for return to their countries of origin.5 Public discussion has since remained myopically focused on the so-called Benin bronzes in major Western collections, including the Tervuen Museum in Belgium, the British Museum in the United Kingdom, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the United States.6 Furthermore, most accounts gloss over the way in which many of these objects were produced with funds generated by the enslavement and sale of fellow Africans.7 More nuance is required, especially from museum professionals living and working in the United States, a nation indelibly shaped by the forcible removal and trafficking of more than 12.5 million Africans against their will.8

Indeed, scholars have yet to undertake systematic studies of the African objects in the United States’ university museum collections and the municipal collections of regional cities, including those of Philadelphia’s flagship institutions.9 Historical African artworks totaling more than five hundred objects are scattered across two departments at the PMA, with the largest concentrations in Costume & Textiles (454). Since the turn of the millennium, the Modern and Contemporary (10) and Prints, Drawings, and Photographs (45) departments have acquired the work of artists born in Africa.10 These haphazard practices reflect the joint decision in 1943 between the PMA and the Penn Museum (formerly the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology) to divide their collections based on the specious yet widely prevalent distinction between “artworks” created by predominantly European-descended individuals and “artifacts” created predominantly by individuals of non-European descent. These taxonomies share the same intellectual roots as the physical violence of white supremacy: the so-called encyclopedic museum grows directly out of the violence of the settler-colonial project from which museums in the United States derive their collections and the lands they occupy.11

Most historical African objects in the PMA collection were part of larger gifts in which donors could not be convinced to break up.12 However, the PMA has not prioritized its African art holdings at all, neither hiring staff curators with the requisite expertise nor publishing information about the collections on its website until Whitham Sánchez proposed this project for the Mellon Fellowship in spring 2021. In line with wider trends in the industry, the PMA lacks a range of perspectives and knowledge in both its leadership and its positions that require specialized knowledge (curators and librarians), neither of which reflect the demographics of the city, which is 43 percent Black and 16 percent Latine/Hispanic.13 While US museums have increased their diversity in the last five years, following a period of stagnancy between 2015 and 2018, most of the inclusion of particularly Black and Hispanic employees remains in “people-facing” positions.14 Philly Necrofutures—launched in the winter of 2022 to address this dearth of resources within the institution—almost certainly catalyzed the creation of the Brind Center for African and African Diasporic Art.15

Philly Necrofutures contributes to long-standing discussions in art history and the digital humanities about the ways in which archives and their absences reflect racist, sexist, and classist hierarchies of knowledge.16 These conversations, primarily among scholars of color in both disciplines, were brought forcibly to the attention of white academia in 2019 with the publication of Saidiya Hartman’s powerful book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments.17 Through what Hartman elsewhere termed “critical fabulation,” Black scholars’ deployment of speculative, empathetic historical narratives grapples with the power structures governing how humans gather, conserve, and deploy artifacts and information, and thus make history itself.18 These Afrofuturist reimaginings are predicated on the excavation of colonial archives, what Pitt Rivers curator Dan Hicks terms “necrographies.”19 Combining the words necrology (the study of death) and geography (the study of terrestrial space), Hicks’s term encapsulates the process of identifying, cataloging, and analyzing repositories of physical violence and attempts at cultural erasure.

As a non-Black Latina scholar, I (Whitham Sánchez) bring an intersectional feminist lens to my study of Black material cultures and historiography. I pair an emphasis on the phenomenological qualities of these artworks with a critical, analytical approach to the texts and institutions that frame, interpret, and support them. My expertise provides grounding for the work of digital cultural preservationists like Smith.

Combining our complementary specializations, Philly Necrofutures offers a thoughtful and sustainable public presentation of under-resourced Black material culture at the PMA. Our primary concerns—outlined below—included assessing the suitability of available technologies and identifying financial and institutional constraints on their adoption, as well as the broader ethical approaches to sharing these works in ways that prioritize heritage bearers locally and on the African continent.

Museum Infrastructure and Student-Led Research

Art historians use a variety of methods to try to understand a work’s life story, from its arrival in an art museum in North America back to its beginnings in communities in sub-Saharan Africa. Collectors’ and dealers’ account books can sometimes be used to trace the object’s geographic origin. Government records might detail whether the work was commissioned for the international art market by colonial officers or created for Indigenous use and then bought or stolen. Comparing artworks across multiple museum and private collections enables scholars to identify the hand of a single carver, weaver, or other maker.20 Traveling to the continent to live with descendant communities, gather oral histories, and look at related works enables art historians to determine continuities and changes in style and function of a given art form over time.21 These visits also offer opportunities for museums to return works seized illegally or unethically.22

My (Whitham Sánchez) first concern on combing through the PMA’s collections database, The Museum System (TMS), was correcting the factual errors and negative stereotypes in as many of the object records as possible. Over several weeks, I worked with the collections information manager and the collections assistant in the Department of European Paintings to develop new protocols for cataloging African artworks in TMS.23 Although some free text fields were easily edited, my primary struggle was classifying the works within the existing structure predicated on the Getty Research Institute’s Art and Architecture Thesaurus (AAT). The AAT reflects the myopic understanding of cultural production endemic to the GLAM industry.

These predetermined selections—sculpture, painting, print, and so forth—reflect European aesthetic concepts and are often inappropriate for the majority of the world’s cultures. For example, the aesthetically and spiritually powerful figural sculptures termed waka sran (fig. 1), created since the 1700s by Baule-speaking makers in contemporary Côte d’Ivoire, exemplify the challenges of caring for African works within neocolonial systems.24 The example in the PMA is a finely carved female figure adorned with two slim strands of red beads and covered with complex abstract geometric patterns that traverse the stomach and cheekbones and skim the hairline. Such a work is the physical manifestation of an individual’s otherworldly counterpart, termed blolo bla, which allows the komien (specialist) to discern the cause of a client’s physical or psychological distress. The figure’s powerful yet contained pose, downcast eyes, and complex decoration instantiate the holistic balance that the komien can facilitate for their client.25 Forms like the waka sran are both sacred sculpture and ceremonial tools as well as time-based, community-driven ephemeral media intended for private use. In the end, the collections management team and I decided to identify the works as sculptures in order to acknowledge the fact that they have been transformed as a result of their current location at the museum. However, this choice reflects exigency and merits revisitation.

Furthermore, the AAT terminology used to refer to artists themselves is predicated on European notions of authorship. Indeed, the terms “unknown” and “anonymous” fail to account for the colonial conditions that resulted in these artworks’ arrival in museums.26 Artists are frequently neither unknown nor anonymous to members of their community of origin, but that information remains largely lost to us in written form today because it went unrecorded by various people along the chain of transfer from the continent to the United States, typically via Europe. The first generation of American art historians working at the height of the Civil Rights Era and funded by Cold War “soft diplomacy” organizations, like the Peace Corps, were able to attribute names to some of these early artists by speaking with elders then still alive.27 The loss of information makes the process of determining who might be interested in these works in African communities today particularly challenging, requiring significant resources to support provenance research in European colonial archives and oral history collection on the continent.

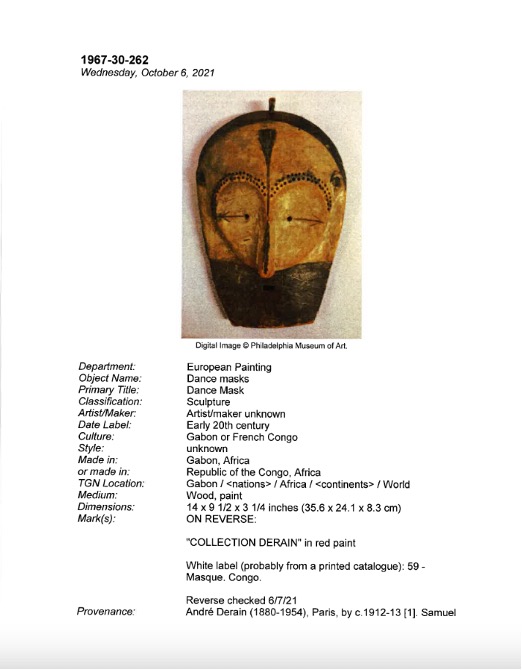

Once the PMA’s database was in order, I turned my attention to assessing specific works in the collection. My primary aims included determining each work’s provenance, gathering information about the work’s original use and function in western and central Africa from existing scholarly literature, and identifying related works in other public and private collections. Given the centrality of connoisseurship and material analysis to research on historic African arts, it was imperative to study the works in the museum’s off-site storage facility. This visit yielded important insights, perhaps most notably the dating of a facial covering for a masquerade from what is today Gabon (fig. 2).

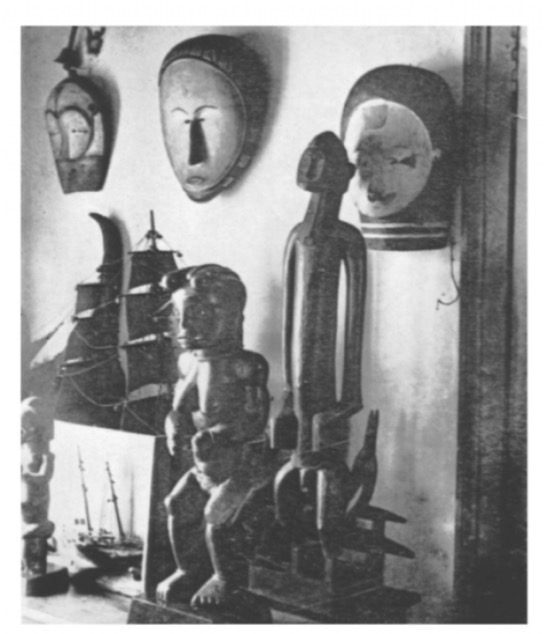

While the photographic image for this work in the TMS database (fig. 3) left me with questions, visual examination of the object in the museum’s off-site storage facility confirmed my initial assessment: this mask had once belonged to the French painter André Derain and was, until recently, believed to be lost. The scale, color, and markings on the masquerade facial covering were consistent with those in the 1912 photograph of the artist’s studio (fig. 4). Turning the mask over, I observed the phrase “collection Derain” in red ink along the back (fig. 5). While it is unclear how the work passed from Derain to Samuel S. and Vera White, who donated it to the museum, we can postulate that either Paul Guillaume or Pierre Matisse—the two most successful dealers on either side of the Atlantic—were involved in the sale.28 The photograph also enables us to attribute a general date to the work, probably within the first decade of the twentieth century. While it is possible that the artwork was created before it was documented on display in Derain’s studio, further research is necessary to determine more about the timing and conditions of its commissioning.

Unlike the other object carved by an unidentified Fang artist currently in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection depicted in the studio photograph, the PMA example was produced specifically for export to European markets, as evidenced by the absence of holes along the rim through which raffia would have been attached.29 Between 1895 and 1905, French colonizers deployed increasingly escalating levels of violence against Indigenous Gabonese people to maintain high levels of rubber production.30 Based on the account of the Catholic missionary Henri Trilles, scholar Louis Perroit postulates that Fang-speaking communities developed a new form of masquerade termed ngongtang.31 Translating loosely to “young white woman,” the mask was intended to harness and control the Europeans’ destructive spiritual power.32 The museum’s mask can thus be understood as the product of a particularly fraught set of relations between the Gabonese maker and the European colonizer who may have commissioned it.

I (Whitham Sánchez) provided students in my “Introduction to Arts of Africa” course at Villanova University with the opportunity to contribute to Philly Necrofutures. Under my supervision, students conducted research on the artworks in the PMA’s European Paintings department. While students were unable to see the artworks in person, they utilized the extensive photographs generated during my visit to the museum’s storage unit as well as visits to other area collections, including the Barnes Foundation and the Penn Museum, to develop their visual-analysis skills. The final projects for our course were two thousand-word curatorial reports as well as 150-word web labels; the former were added to the department files at the PMA while the latter appear on the project’s StoryMap. The Villanova students’ research on the PMA’s collection of African works contributes directly toward our aim to generate a more accurate understanding of the role of African works in the twentieth century—as spoils of colonial incursion, ethnographic artifacts, and aesthetic objects traveling through different but overlapping circuits, adhering to distinct but related definitions of value. Through our partnership with Villanova University, we demonstrate the value of engaging a variety of local stakeholders in the work of research and interpretation of these objects.

Digital Tools to Disrupt Traditional Curatorial Practices

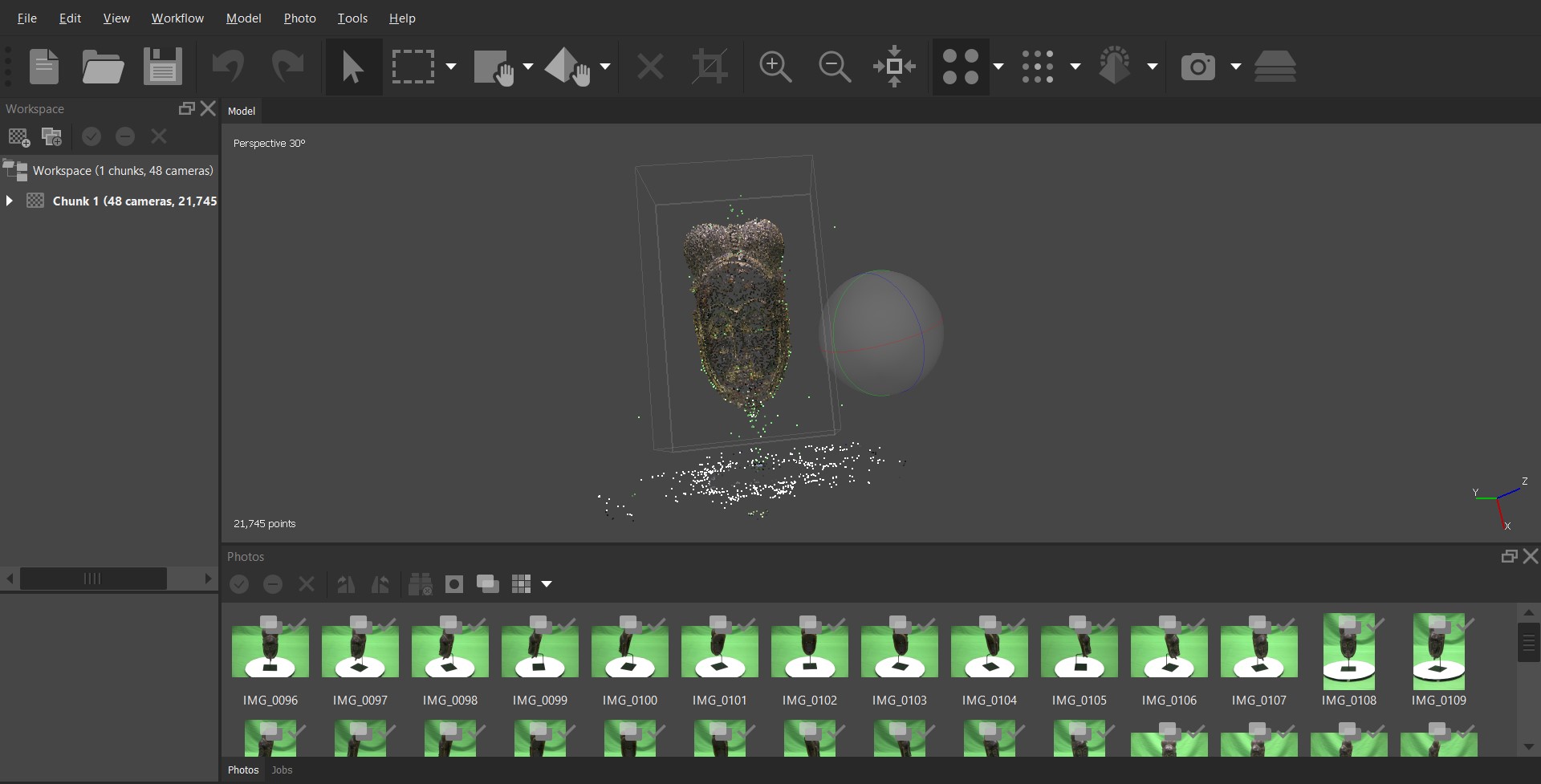

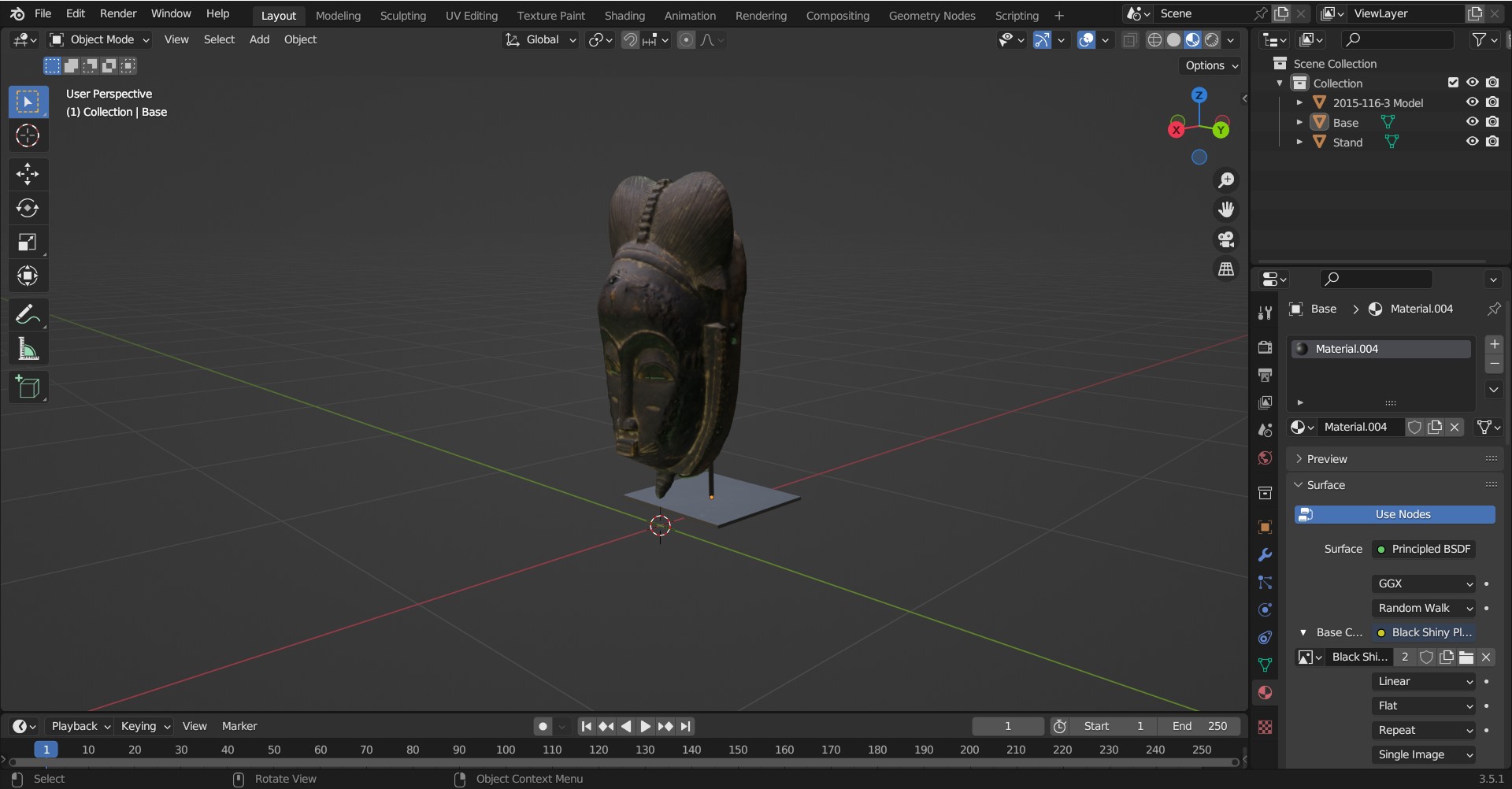

Concurrent with Whitham Sánchez’s material analysis and historical research, I (Smith) began producing three-dimensional models of the African sculptures using the photogrammetry technique (fig. 6). Photogrammetry involves capturing multiple photographs of each sculpture at three to five different angles, depending on the size of the sculpture, and using software to stitch the photographs together, removing any points that are not related to the object. Nine works were identified as suitable candidates for photogrammetry based on their structural integrity.33 For example, the blolo bla in figure 6 was durable enough to be handled repeatedly during the photography process.

Curatorial staff coordinated with the photography studio to arrange a pilot photography day for me and a museum photographer to determine our individual equipment setup since we would be working in a shared space, which resulted in additional African sculpture being photographed and modeled. After capturing about fifty to sixty photographs of each sculpture, the images were imported into the Agisoft Metashape photogrammetric-processing software (fig. 7).34 The model files were then imported into the Blender three-dimensional modeling software program for final editing and export (fig. 8).

Initially, I identified Wikimedia Commons, the media repository of free-use images, sounds, other media, and JSON files as a potential platform to ensure that the images and information about these works are available to the broadest possible audience.35 Wikimedia Commons is part of the Wikimedia Foundation’s series of tools that have unique functions but are publicly editable by anyone who creates an account. I was first introduced to the Wikimedia universe through a project editing Wikidata records for Black artists in the PMA’s collection to enhance their digital visibility.36 Wikidata is connected to the Google Knowledge Graph, which allows additional data related to a Google search to be displayed on the information panel located on the top right of the search results. I expanded my Wikidata work to include hosting an edit-a-thon for Black artists in other Philadelphia-area collections and working with fellows through the Temple University Libraries Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio to develop data visualizations based on Wikidata queries. In sum, the democratic nature of the Wikimedia universe’s crowdsourcing data technologies enables scholars and other knowledge bearers to effectively counter dominant histories for the digital record.

While I was given explicit permission from the museum to post the media files to the platform, an incident with another user about whether the images fit the criteria for open access redirected my progress with this part of the project, prompting us to reconsider our utilization of the platform. My direct communications with that user to clarify the scope and authorizations needed to include reproductions of these works on Wikimedia Commons were met with open hostility. They challenged my understanding of the copyright policies for the platform despite my insistence that I had the support of my institution, including the museum’s head librarian, my direct supervisor, who worked with our legal counsel to develop our image-use policy. The user threatened to have my account blocked from future editing, at which point my supervisor advised that I speak with two local Wikipedians about how to move forward.

In my communication with the Wikipedians, we considered the two copyright issues at hand. First, there is the issue of the copyright belonging to the makers: any sculpture with a creation date more than 120 years ago would automatically enter the public domain. Of the thirteen works for which a creation time period could be established, seven of the objects could be more than 120 years old; however, the provenance research could not determine their conclusive dates, and thus all of the markers are listed as unknown.37 Second, while the copyright belonging to the photographer is held by the institution, as the photographs were each captured by the staff photographer, the Wikipedians noted that the public-domain policy for copyright and image use is not explicitly detailed on the institution’s website. As such, it is difficult to prove my claims of permission to any Wikimedia Commons editors who challenge my authority to post the images. I considered posting photographs I captured myself from the photogrammetry process, but these images were not of sufficiently decent quality to share for purposes not related directly to photogrammetric processing. In fact, the photographs that were used for this process are intentionally flat and include extraneous data, like the turntable the object is placed on and the green screen, which assisted with removing the background as the three-dimensional model was processed. Lastly, we discussed adding language to my public profile to describe my use of the platform to demonstrate that I am acting in good faith as I post images.

At this point I considered the likelihood of the museum adding language around public domain specifically to the fair-use policy on the institution’s website and the fact that only one of the sculptures could be confirmed as having been made during the nineteenth century. With this information in hand, I opted not to circumvent the challenge made by the hostile Wikimedia Commons editor and ultimately chose not to upload any of the works to Wikimedia Commons. Instead, I uploaded three-dimensional modeled sculptures to the Sketchfab three-dimensional viewer platform, forming a collection called PMA African Sculptures (fig. 9). I then filled in the model properties, including setting the title as the sculpture name and accession number and adding the curatorial label in the description box with a research attribution credit to Whitham Sánchez and her students at Villanova. Sketchfab enabled me to embed the individual models into external websites. This was critical for our project because we wanted to create a geographic visualization for the works using the ArcGIS platform, and model files cannot be directly uploaded to that platform.38

PMA African Sculptures

by synatra

on Sketchfab

Fig. 9. Three-dimensional models of African sculptures from the Philadelphia Museum of Art collection, https://sketchfab.com/synatra/collections/pma-african-sculptures-cdbeb915cdce4d0e87c29bec889b33fc

My institutional affiliation with Temple University Libraries provided me with free access to the ArcGIS StoryMaps tool, which allowed us to integrate the contextual data, images of the sculptures, and the three-dimensional model collection within a single digital platform.39 The user can scroll through the StoryMap, which begins with a brief summary of the project that leads into the mapping visualization. This visualization is formatted as a guided tour through which the user travels from central Mali, southward through West Africa, and inland to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Each point on the map has an associated label with an image of the sculpture, its title and accession number, the curatorial label, and a research attribution. For the ten sculptures shown as three-dimensional models, there is a button to view the model externally on Sketchfab. Below the map, the entire interactive collection of African sculptures and a TikTok video showing the photogrammetry process are embedded directly into the site.

The inclusion of the map in the Philly Necrofutures project is an effort to address the moment of rupture and the colonial legacies of the twentieth century. These artworks were removed from their geographic contexts and housed in the European Paintings department of a predominantly white institution. They were subsequently given limited institutional attention that focused on their histories of provenance—and thus adjacency to Euro-American artists and collectors—instead of their African cultural origins. Underscoring the art-historical and anthropological research through the inclusion of the curatorial label text in the description field for the Sketchfab documentation grounds the models in the histories of their makers and intended purposes.

Fig. 10. Recorded demonstration of augmented reality iOS application on Sacred Geographic Superimpositions story map, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1osMhwNIZXbs-BVH2vY-7dXVxUf5HCsIU/view?usp=share_link © Synatra Smith

The Philly Necrofutures sculpture models also appear in my (Smith’s) augmented reality project titled Sacred Geographic Superimpositions alongside models of public artworks by Black artists in Philadelphia and of African instruments in the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection (Blockson Collection) at Temple University Libraries.40 Like in Philly Necrofutures, each artwork in Sacred Geographic Superimpositions includes a short pop-up label with text, an image of the artwork, and a “Read more here” link to an external website with additional information about the artwork, if one exists. I also developed an iOS application using the Unity game engine software to enhance the images in the pop-up label with an augmented reality experience. When the mobile application is deployed, the user points the device’s camera at the photograph in the pop-up label on the map, and an associated rotating or pivoting three-dimensional model of the artwork reinterpreted as an altar appears on the device’s screen (fig. 10).

As I was developing this project, I sought to reconcile the criticisms of Afrofuturism as a movement that “treats Africa as a mythical continent and an unfulfilled fantasy of sorts.”41 My intentional blending of art-historical and anthropological research with speculative technocultural curation is rooted in the widespread African American artistic and intellectual tradition of seeking to understand one’s partially unknowable past as a result of the transatlantic trafficking of enslaved people. Commenting on the combination of Egyptian and outer-space imagery used by the influential musician Sun Ra, sociologist Tricia Rose asserts, “If you’re going to imagine yourself in the future, you have to imagine where you’ve come from; ancestor worship in Black culture is a way of countering a historical erasure.”42 In contrast to more generalized projects, Sacred Geographic Superimpositions honors and preserves specific temporary and semipermanent public artworks in Philadelphia. Additionally, the altars pull from my own spiritual practice, which participates in the African diasporic traditions to syncretize Indigenous, European, and African practices as a response to the complex social relations between these groups throughout the western hemisphere.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical art history and data curation consider what kinds of displays are appropriate for culturally sensitive materials and how representations of marginalized communities function within larger image ecosystems structured by white supremacy.43 The digital aspect of Philly Necrofutures combines critical technocultural discourse analysis (CTDA) with Afrofuturist theory. While the former considers the relationship between the tool, the user, and the way the tool is used, the latter offers the philosophical apparatus to understand the impact of technologies on Black history and culture. CTDA stresses the importance of the interfaces with which the user interacts to understand the technology itself.44 Media studies scholar Tanner Higgin notes that video games and other digital media are derived from real-world structures and experiences and often replicate age-, gender-, and race-based biases. He writes, “Blackness is only allowed visibility in very specific and calculated moments that enact the desires of the dominant audience and fit into their cultural imaginary.”45 For example, in the globally popular, massively multiplayer, online role-playing game World of Warcraft, the human race is coded as European, while other races are typed as non-white. In contrast, the game Aurion: Legacy of the Kori-Odan provides a refreshing alternative in which all characters are phenotypically Black. Created and developed by the Cameroonian engineer Madiba Guillaume Olivier, Aurion was the first video game by, about, and for Africans when it launched in 2015. The replication of racialized hierarchies in digital media noted by Higgin can be directly connected to the misuse of cultural heritage items in the entertainment industry. While our intention is to share these works with the public in order to remove barriers for access throughout the knowledge commons, we also considered the potential harm of appropriation that could be enacted by unintended audiences.46

Returning to CTDA, interdisciplinary scholar of library and information science André Brock defines technoculture as the means of understanding the material and epistemological underpinnings of how technology and culture intersect in contemporary life. Distinguishing Afrofuturist utopian thought from dominant white supremacist notions of modernism, he identifies the central propelling question of technoculture for people of African descent: “What if modernity’s alienation is a feature and not a bug for Black folk?”47 In other words, twentieth- and twenty-first-century technologies were not constructed for Black users and are therefore fundamentally alienating for them. Brock’s astute rhetorical question necessitates that we remain attentive to the ways in which Philly Necrofutures could simultaneously subvert and inadvertently reinforce this alienation.

Conclusion: Africanist Historical Research and Black Speculative Practice as a Collaborative Antiracist Cultural Heritage Toolkit

Digital humanities scholar Bethany Nowviskie explains that cultural heritage sources (such as archival records, material culture, language, and song) are fundamentally functional and can therefore be considered “active technologies . . . still running code and tools that hum with potential.”48 We explored the myriad ways our combined skill sets could enhance the visibility and utility of the PMA’s collection of African artworks through scholarship and technology. The use of photogrammetry and StoryMaps to present scholarly interpretation “offers us new ways to map, view, encode, or decode traditional cultural systems and symbols with dynamically changing information, sometimes digital in form and closely linked with the development of a techno-cultural network.”49 While these works have experienced an ontological death as a result of their removal from their communities and imprisonment in museum storage, our project offers resuscitation by utilizing digital tools to draw attention to these histories, a form of life in death, thus necrofutures.

While the sculptures may exist within the European Paintings department at the PMA, the map is a direct effort to disrupt those proprietary claims, stressing their geographic and cultural foundations instead. By selecting open-source and low-cost proprietary tools, we aim to ensure that our methodology can be replicated by independent researchers and/or other institutions to address under-resourced collections of cultural heritage belonging to historically marginalized populations. At a moment when institutions throughout the GLAM industry are facing increased scrutiny and pressure to address their failures to promote diversity, equity, inclusion, and access in their collections, programming, and staffing, we offer Philly Necrofutures as our pragmatic approach to addressing these institutional limitations.

Cite this article: Synatra Smith and Hilary Whitham Sánchez, “Philly Necrofutures: Digital Curation to Counter the Under-Resourcing of African Collections at the Philadelphia Museum of Art,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 2 (Fall 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18261.

Notes

- Philly Necrofutures derives from initial conversations held while Smith was CLIR/DLF Postdoctoral Fellow in Data Curation for African American Studies at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Temple University Libraries, and Whitham Sánchez was Mellon Graduate Fellow in the Department of European Paintings at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Our project was supported by grants from the Lepage Center for History in the Public Interest at Villanova University and the Sachs Program for Arts Innovation at the University of Pennsylvania. We would like to thank Jennifer Thompson, the Gloria and Jack Drosdick Curator of European Painting and Sculpture and curator of the John G. Johnson Collection, for ensuring that we were able to examine all the works in person despite all of the logistical challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as Paul Brinkley, Grant Cox, and Kurt Christian for their adept assistance. We are also grateful to Tim Tiebout, museum photographer, for his thoughtful efforts to showcase the works—especially those intended to be seen in motion—in a way that gestures to their original meanings and functions. We also want to thank him for sharing his expertise of photogrammetry best practices. ↵

- Mark Dery, “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose,” in Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture, ed. Mark Dery (Durham: Duke University Press, 1994), 180. On the aesthetics of Black science fiction, see Faithe Day, Synatra Smith, Jodi Reeves Eyre, John MacLachlan, and Christa Williford, “A Third Library Is Possible,” Curated Futures Project, 2021, https://futures.clir.org/about. ↵

- Lidia Kniaź, “Capturing the Future Back in Africa: Afrofuturist Media Ephemera,” Extrapolation 61, no. 1 (2020): 54. ↵

- Day et al., “A Third Library Is Possible.” ↵

- Felwine Sarr and Benedicte Savoy, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Towards a Relational Aesthetics, trans. Drew S. Burk (Paris: Ministère de la Culture Française and Université Paris Nanterre, 2018). ↵

- Phillip Ihenacho, “Benin Bronzes: Whose Restitution Is This Anyway?,” Art Newspaper, May 31, 2023. ↵

- Moyo Okediji, “On Reparations: Exodus and Embodiment,” African Arts 31, no. 2 (1998): 8–10. ↵

- David Eltis and David Richardson, “Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database—Statistics,” accessed July 10, 2023, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database#statistics. ↵

- Whitham Sánchez’s book project Art/Artifact: African Material Cultures in Philadelphia’s Museums, marks the first comprehensive study of the role of African material cultures in Philadelphia’s three flagship institutions: the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Penn Museum, and the African American Museum in Philadelphia. Art/Artifact explores notions of cultural patrimony and authenticity among cultural leaders along the color line from the Harlem Renaissance to Black Lives Matter. ↵

- These numbers include the internationally renowned white South African artists William Kentridge and Marlene Dumas. ↵

- Tukufu Zuberi and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, eds., White Logic, White Methods: Racism and Methodology (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008); Theresa Stewart-Ambo and K. Wayne Yang, “Beyond Land Acknowledgement in Settler Institutions,” Social Text 146, no. 1 (March 2021): 21–46. ↵

- These statistics are derived from Whitham Sánchez’s research into the Philadelphia Museum of Art archives and the European Paintings departmental records, May–July 2021. ↵

- United States Census Bureau, “United States Census, Philadelphia—Quick Facts,” 2022, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/philadelphiacountypennsylvania. The US Census uses the terms Latine and Hispanic interchangeably; the former refers to those born in the United States with roots in the Caribbean and South America, while the latter refers to immigrants from Latin America, Spain, and Portugal. ↵

- Liam Sweeney, Dierdre Harkins, and Joanna Dressel, Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey 2022 (Mellon Foundation and Ithaka S-R, 2022), https://assets.ctfassets.net/nslp74meuw3d/6gnnNJOBeDbYImaDPNnyT9/3221a846b1706bd73c552b2eb5931b5e/art_museum_staff_dem_survey_2022.pdf. ↵

- Holland Cotter, “Museums Are Finally Taking a Stand. But Can They Find Their Footing?,” New York Times, July 11, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/11/arts/design/museums-protests-race-smithsonian.html; Anni Irish, “Philadelphia Museum of Art Workers Reach Contract Agreement, Ending Three-Week Strike,” Art Newspaper, October 18, 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/10/18/philadelphia-museum-art-workers-strike-ends-union-contract; “Philadelphia Museum of Art to Establish Center for African Art,” ArtForum, February 24, 2023, https://www.artforum.com/news/philadelphia-museum-of-art-to-establish-center-for-african-art-252534. ↵

- Alexis Lothian and Amanda Phillips, “Can Digital Humanities Mean Transformative Critique?,” Journal of E-Media Studies 3, no. 1 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1349/PS1.1938-6060.A.425; Renée Green, “Archives, Documents? Forms of Creation, Activation, and Use” (2008), in Other Planes of There (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 176–90; Margaret Bruchac, Savage Kin: Indigenous Informants and American Anthropologists (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2018). ↵

- Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019). ↵

- Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 11. ↵

- Dan Hicks, The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence, and Cultural Restitution (London: Pluto, 2020), 3. ↵

- Ezio Bassani, Masterhands—Mains Des Maîtres (Brussels: Cultuurcentrum, 2001). ↵

- Susan Mullin Vogel, “Known Artists but Anonymous Works: Fieldwork and Art History,” African Arts 32, no. 1 (Spring 1999): 40–55. ↵

- “One: Egúngún,” Brooklyn Museum, August 8, 201AD, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/one_egungun; Alex Greenberger, “Scottish University Becomes First to Repatriate Benin Bronze to Nigeria,” ARTNews, March 25, 2021, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/university-of-aberdeen-returns-benin-bronze-1234587803. ↵

- Whitham Sánchez extends her thanks to Renée Baumgartner and Emily Rice for their enthusiastic collaboration outlined above. ↵

- Susan M. Vogel, Baule: African Art, Western Eyes (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997). ↵

- Alain-Michel Boyer, Baule: Visions of Africa (Milan: Five Continents, 2007). ↵

- Alisa LaGamma, “Authorship in African Arts,” African Arts 31, no. 4 (1998): 18–23. ↵

- Kate Cowcher, “Soviet Supersystems and American Frontiers: African Art Histories amid the Cold War,” Art Bulletin 101, no. 3 (2019): 146–66. ↵

- Yaëlle Biro, Fabriquer Le Regard: Marchands, Réseaux et Objets d’art Africains à l’aube Du XXe Siècle (Dijon: Les Presses du réel, 2018). ↵

- For more information about so-called tourist art, see Ruth Philips and Christopher Steiner, Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds (Oakland: University of California Press, 1999). ↵

- Jean Suret-Canale, French Colonialism in Tropical Africa, 1900–1945, trans. Till Gottheimer (New York: Pica, 1971); Xavier Cadet, Histoire Des Fang, Peuple Gabonais (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2009). ↵

- Henri Trilles, Chez Les Fang, Ou Quinze Années de Séjour au Congo Français (Lille: Desclée, De Brouwer, 1912). ↵

- Louis Perrois, “Fang Masks of Equatorial Africa: Relationship, Diversity, Evolution,” Tribal Art 50, no. 1 (2008): 100. ↵

- Again, we wish to thank Jennifer Thompson for facilitating this aspect of our work. We would also like to thank Elysia Petras, a doctoral student in Temple University’s anthropology department, for sharing her photogrammetric workflow with Smith during her graduate externship with the Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio at Temple University Libraries. ↵

- See full photogrammetric workflow via http://bit.ly/pmamaskmodeling. ↵

- The PMA has two systems that work in tandem to manage information about artworks in the collections. While neither is currently accessible to the public, images of the artworks are available for free download on the collections database pages of the museum’s website. ↵

- See http://bit.ly/wikidatablogs for more information about how this project was implemented including a cross-institutional programming collaboration, editing Wikidata records, querying the database using SPARQL, and using Python to generate data visualizations. ↵

- Some of the works are dated to between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which does indeed include dates less than 120 years ago. ↵

- The ethical conundrum of determining the correct protocols for engaging with these works with the permission of and/or in partnership with the “objects” themselves and descendant communities remains unresolved. Identifying those stakeholders through more extensive research and building those relationships requires significant institutional support, in addition to a shift in notions of agency. El Museo del Barrio’s Taino Council, which advises the curatorial team on the care procedures for Cemí/Zemí in the collections, offers a model for working through this issue. The authors hope that by sharing these works digitally, stakeholders will be encouraged to come forward and new relations between the works, the public and the museum can emerge. ↵

- While Sketchfab does offer a free account with limits on file size, ArcGIS Online requires a paid subscription. However, other free mapping tools that offer viable alternatives include QGIS, StoryMap JS, and Mapbox. ↵

- Synatra Smith, “Sacred Geographic Superimpositions: Reimagining Public Art, for Us by Us, as Enshrined Spaces,” ed. Faithe Day et al., Curated Futures Project, 2023, https://futures.clir.org/sacred-geographic-superimpositions. ↵

- Lidia Kniaź, “Capturing the Future Back in Africa: Afrofuturist Media Ephemera,” Extrapolation 61, no. 1–2 (2020): 54. ↵

- Tricia Rose, quoted in Dery, “Black to the Future,” 215. ↵

- Patricia Hill Collins, Fighting Words: Black Women and the Search for Justice (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998); Bethany Nowviskie, “5 Spectra for Speculative Knowledge Design,” April 22, 2017, http://nowviskie.org/2017/5-spectra. ↵

- André Brock, “Critical Technocultural Discourse Analysis,” New Media & Society 20, no. 3 (2018): 1020–23. ↵

- Tanner Higgin, “Blackless Fantasy: The Disappearance of Race in Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games,” Games and Culture 4, no. 1 (2009): 20. ↵

- Ihenacho, “Benin Bronzes”; Kishonna Gray, “Deviant Bodies, Stigmatized Identities, and Racist Acts: Examining the Experiences of African-American Gamers in Xbox Live,” New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia 18, no. 4 (2012): 262, 268. ↵

- André Brock, “Black Technoculture and/as Afrofuturism,” Extrapolation 61, nos. 1–2 (2020): 12. ↵

- Nowviskie, “5 Spectra for Speculative Knowledge Design.” ↵

- Nettrice R. Gaskins, “Afrofuturism on Web 3.0: Vernacular Cartography and Augmented Space,” in Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness, ed. Reynaldo Anderson and Charles Earl Jones (Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2016), 28. ↵

About the Author(s): Synatra Smith is an anthropologist exploring extended reality (XR) and other digital tools to enhance special collections and archival records featuring Black art, history, and culture. Hilary Whitham Sánchez is an art historian specializing in the circulation and interpretation of African artworks during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.