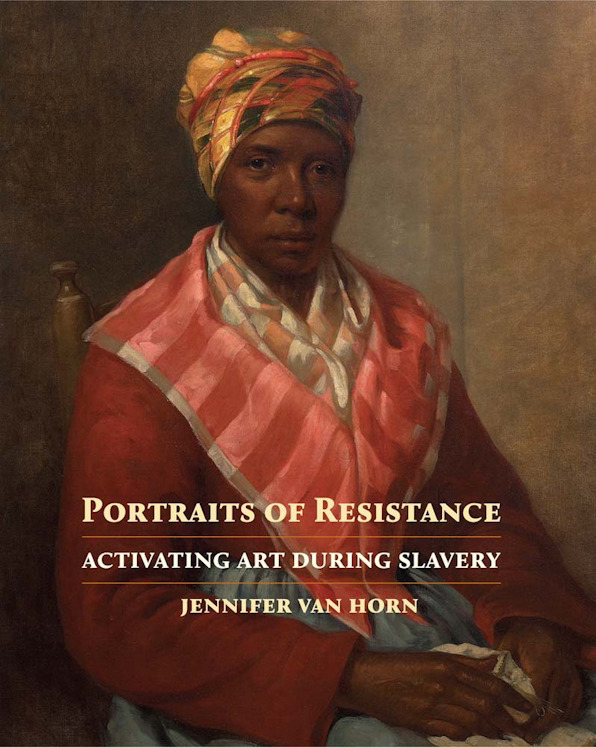

Portraits of Resistance: Activating Art During Slavery

PDF: Robertson, review of Portraits of Resistance

Portraits of Resistance: Activating Art During Slavery

By Jennifer Van Horn

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2022. 344 pp.; 105 color illus.; 34 b/w illus. Hardcover: $60.00 (ISBN: 9780300257632)

Jennifer Van Horn’s Portraits of Resistance: Activating Art During Slavery is a tour de force, complex in its structure and innovative in its methodology.1 The book analyzes the work of enslaved African Americans, both as art makers and as viewers, and the implications of that resistant activity. As Van Horn states in her conclusion: “Portraiture in early America cannot be separated from questions of racialized personhood, but was fundamental to forming them” (276). In other words, as scholars have argued for decades in other arenas of American culture, there are no separate white and Black spheres of activity or representation. American visual culture, just as literature and music, is built on the production of and response to Black makers.

Van Horn introduces her argument with a classic anecdote from one of the founding fathers of American portraiture, Gilbert Stuart. On his return in 1826 to Rhode Island, where he was born, Stuart declared: “Neptune was my first master. The first idea I ever had of painting the human features I received from seeing that old African draw a face” (1). This story belongs as a founding statement of American art together with Benjamin West’s famous response to first seeing the Apollo Belvedere in Rome: “How like a Mohawk warrior.” West, in that story, gave himself the same status of authenticity and originality as Greco-Roman artists, claiming that he, unlike his derivative Italian hosts, had witnessed the human body in its natural state and was thus inspired like the sculptor of the Apollo. Stuart’s story inverts this hierarchy of influence and indebts his sophisticated art, the most cosmopolitan being practiced in the United States at the time, to the humble sketches on barrel heads made by his neighbor, the enslaved Neptune Thurston. For Stuart, his statement indicates the exceptional range of his artistic journey, standing as an emblem of that arrival into full artistry for all (white) American artists. What is extraordinary, of course, is that Stuart makes his progenitor in art an enslaved man. One can tease out the many conscious meanings of this story for Stuart, but one can also, as Van Horn does, suggest the unconscious realities of the effects of slavery on white cultural production. What is equally astonishing for me is the fact that I had never heard the anecdote before. West’s story is historiographically canonical; Stuart’s should be. After, one suspects, Van Horn’s book is fully absorbed into the field, it will be.

None of Neptune Thurston’s drawings survive. Van Horn does an incredible job of finding equivalent visual images and verbal descriptions but makes the strong and convincing case that absence in the archive can speak as eloquently as presence. She briefly apologizes for speculating as much as she does—for using words like “probably,” “likely,” and “possibly” so often—but drawing on the works of scholars such as Saidiya Hartman, Van Horn makes the case that such speculation is both necessary and productive: “Absence [is] a starting point for investigation; absence is not a reason to stop asking questions” (19).

Van Horn’s speculations, however, are not free-form but thoroughly evidence-based. Her work in the archive is impressive, as is her command of the literature. But it is the complex structuring of the book that makes it work. Every starting point finds its visual or intellectual rhyme. You have to admire an author who sandwiches her account between two portraits of presidents: the book begins with Stuart’s Landsdowne portrait of George Washington and an illustration of an enslaved person drawing with charcoal; the book ends with Gordon Parks’s photos and Henry Roseland’s racist image of two formerly enslaved people reverently viewing a portrait of Abraham Lincoln. As Van Horn writes: “Portraiture was both a technology used to deny Black agency and aesthetic achievement and a means for African Americans to reaffirm their humanity and creativity” (10). Led by the book’s narrative, the reader, over and over again, returns to this point with eyes that begin to see as Van Horn’s argues we must see; she sticks her landings perfectly.

In the introduction, Van Horn uses the Stuart and Neptune Thurston story to lay out her argument in a series of sections that first provides examples of the kind of drawings Thurston must have made and then sets Black representation and Black making within the Atlantic traditions of elite portraiture. As representative of her astonishing ability to dig deeply, Van Horn ends the introduction with Thomas Mickell Burnham’s The Young Artist (1840), a genre painting that represents a white boy drawing, on the bottom of a tub, a “portrait” of a Black youth who poses for him. This reversal of Stuart’s story is inspired by it, and, Van Horn suggests, Burnham’s painting supplies a vivid demonstration of the active opposition to narratives of Black agency in making art of consequence. This is the raison d’être of the book: to overcome the habitual, unconscious, and powerful resistance to recognizing the presence of enslaved Black art making as an origin for any possible narrative of American art.

In the following five chapters, Van Horn focuses on a singular object or art action, which she uses as a springboard for wider analysis. In the first chapter, “Making Portraits,” she focuses on the one surviving original portrait by Prince Demah, a Black enslaved portrait painter whose education was paid for by his owners in the hopes of creating a new income stream for themselves. Van Horn uses this portrait as a catalyst for considering the nature and extent of Black presence in colonial portraiture primarily in Boston and New York, with an interesting emphasis on women sitters. Demah was a “project” for his enslavers, Christian Barnes and her husband, Henry Barnes. Through a scrupulous and almost relentless analysis of Christian Barnes’s letters, Van Horn is able to suggest something of the complex internal dynamics between her and Demah’s mother, Daphney, who was also enslaved by the Barneses. Demah and Daphne begin to appear as actors in the historical record, not shadows, objects, or victims.

The second chapter, “Fleeting Portraits,” focuses on Edward Savage’s The Washington Family (1789–96) and the inclusion of Christopher Sheels, George Washington’s enslaved personal servant, who stands to the right of the family. Van Horn methodically dismantles the legends surrounding the painting and Sheels’s portrait within it, suggesting both Sheels’s status as an imposing and dignified proud figure (he literally stands over the family), the complex racism of the portrayal (Sheels is an elite object, akin to Martha’s fine chair), the reworking of the portrait (how Sheels’s likeness morphs in the reconception of the image as an engraving) and finally Sheels’s resistance to his depiction by Savage. Van Horn writes that her attempt to recover the richly layered meanings of Sheels’s presence “is intended as a step forward in the long process of acknowledging the disremembering of Washington’s enslaved attendant” (120).

In the third chapter, “Haunted Portraits,” Van Horn “begins and ends with the search for a portrait, a depiction of Henry Ryan, commissioned by the man who enslaved him, Thomas Pugh” (122). Here Van Horn moves deeper into the Plantation South, to Louisiana, and discusses several portraits of enslaved people commissioned by their owners. She begins to map out a landscape of Black looking that she develops in the next chapter, “Viewing Portraits,” which focuses on formerly enslaved women’s memories of the portraits that hung in their enslaver’s plantations before the Civil War. Van Horn makes a persuasive case for the complicated response of enslaved viewers to the portraits of their white owners, one that is aesthetically complex.

In the final chapter, Van Horn focuses on iconoclasm, the destruction or mutilation of portraits of white owners by freed Black people during and after the Civil War. She argues that these are acts of aesthetic judgment. She focuses on John Wollaston’s portrayal of Daniel Ward in an eighteenth-century family portrait that was “rescued” by its previous owners from a cabin where it was being used as a fire screen. The painting had been covered in newspaper when Charles McGillivrary took it back, and Van Horn brilliantly traces the various ways to interpret this papering over, ending with different vodun responses. She then rereads the painting’s subsequent conservation and exhibition in a gallery dedicated to Southern “masterworks” as another, and more pernicious, papering over of the past (258).

In the epilogue, Van Horn shifts her attention to twentieth-century portraits and meditates on Archibald Motley’s painting of his grandmother Emily Sims Motley, titled Mending Socks (1924). An oval portrait of the grandmother’s former white enslaver, Emma Kittredge Sims, hangs on the wall, bisected in Motley’s depiction so that only its right side is visible. Van Horn elegantly dissects the Motleys’ positive account of the portrait of her enslaver (“‘The painting tells a beautiful story,’” in Motley’s words; 264) and allows its partial appearance to make her whole argument: we can only see this standard mid-nineteenth-century portrait of a white woman, one of many thousands of similar works, incompletely (264). Its absent half represents all the silences and erasures in the archive and in our historiography and scholarship; its visible half is shrouded in stories that conceal a more complex and ambivalent reaction than the Motleys’ words allow. This is the story of American portraiture Van Horn wishes to place at the center of our understanding of American art as a whole. It is significant that not only is the painter of this work Black but so is the viewer within the painting. It is also significant that they are family, in a lineage that extends from slavery in the South to freedom in the North—and finally into this book. We, Van Horn argues, must realize that we are all also part of this lineage.

My one regret is that the book does not consider the very substantial body of portraiture of free Blacks in the North, which must also be understood within the crucible of slavery. These works occasionally appear in the book but are not subject to the same depth of analysis as the portraits of enslaved figures or the responses of enslaved people to art. I understand Van Horn’s decision to focus so fully on the South: her reasons are ideological and methodological (and practical, no doubt). But I do hope that her work stimulates research into Northern Black portraiture and audiences. For example, the very noteworthy and coherent group of images of Black ministers, comparable to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century engravings of British clerics and just as important to their viewing publics, demands attention. Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw’s excellent 2006 book Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century assembles a few of these works, but there are many more. Other neglected bodies of material include portraits of craftspeople, fraternal organizations, and books of African American worthies, such as William J. Simmons’s Men of Mark. I hope Van Horn’s work indicates the start of a major shift in our attention and scholarship.

Cite this article: Bruce Robertson, review of Portraits of Resistance: Activating Art During Slavery, by Jennifer Van Horn Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19004.

- Bruce Robertson is a member of Panorama’s Advisory Council. ↵

About the Author(s): Bruce Robertson is Professor Emeritus History of Art and Architecture, and Director Emeritus Art, Design and Architecture Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara.