Rufus Porter’s Curious World: Art and Invention in America, 1815–1860

Curated by: Laura Fecych Sprague and Justin Wolff

Exhibition schedule: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, December 12, 2019–May 31, 2020

Exhibition catalogue: Laura Fecych Sprague and Justin Wolff, eds., Rufus Porter’s Curious World: Art and Invention in America, 1815–1860, exh. cat. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019. 152 pp.; 87 color illus.; 19 b/w illus.; Hardcover: $39.95 (ISBN: 9780271084954)

Discovering the “Yankee Da Vinci”

Cultural critics have long warned us that technology can threaten the singularity of the art object. They forecast that new forms of media will end culture as we know it. Walter Benjamin and Marshall McLuhan detailed the deterioration of art’s unique societal contribution and its higher purpose in the face of changing information systems.1 These portents weigh particularly heavily in 2020 as we scramble to reinvent working and learning digitally during the COVID-19 pandemic. How refreshing, therefore, to spend time in the world of Rufus Porter, the nineteenth-century polymath who approached art and science as intertwined disciplines necessary and vital to one another. Porter’s contributions to both realms are the subject of an exciting exhibition at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Full of new discoveries, the show examines a man best known as a New England mural painter and founder of this country’s longest-running periodical, Scientific American. Thanks to dogged research by art historians Laura Fecych Sprague, consulting senior curator at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, and Justin Wolff, professor of art history at the University of Maine, Orono, Porter and his larger artistic, philosophical, and scientific world come vividly to life. Sprague and Wolff have brought together Porter’s murals, miniatures, scientific devices, paintings, publications, and letters to illustrate the artist’s lifelong pursuit of knowledge and its transmission on micro and macro scales.

The exhibition is arrayed over two large galleries and arranged roughly chronologically to provide an easy means for visitors to follow Porter’s emergence as an itinerant portraitist, muralist, author, publisher, and inventor. Sections such as “American Enlightenment,” “Itinerant Artists,” “Porter’s Early Endeavors,” “The Polymath at Work,” “Rufus Porter’s New York Newspapers,” and “Aerial Navigation” focus on breakthrough projects that anchor the artist’s career but also situate him within the larger cultural worlds in which he circulated and from which he drew inspiration. The curators have resisted the impulse to stray too far from Porter’s own art and inventions in their narrative. Luckily, Porter’s catholic interests provide them with a natural means to explore the history of a modernizing nation through a single, fascinating career.

Rufus Porter was born in Maine in 1792 and lived through a century of remarkable discovery. His formal education began and ended at the Fryeburg Academy, one of the country’s oldest private schools, although Porter continued to learn from friends, colleagues, and public institutions throughout his life. As a young artist, he settled in Portland around 1811 and established himself as an itinerant miniature painter and muralist. Restlessly peripatetic, he moved to Boston, New York, and Washington, DC, filing twenty-four patents, penning art and technological manuals, and editing several periodicals along the way. Porter was, however, an abysmal businessman, and unlike fellow artist-inventors such as Robert Fulton and Samuel F. B. Morse, he died in 1884 in relative obscurity.

The Rufus Porter Museum opened in 2005 in Bridgton, Maine to preserve the artist’s legacy, however, this exhibition provides the first comprehensive survey of Porter’s work at a major institution. To date, literature dedicated to Porter has disproportionately focused on his murals.2 Jean Lipman, and more recently Linda Carter Lefko and Jean Radcliffe, have researched Porter as a painter of New England interiors and charted his influence on other muralists of his day.3 Lipman also published the first comprehensive study of Porter’s full career, although her lack of footnotes has made her scholarship difficult for subsequent researchers to rely on as a resource.4 Porter also appears in explorations of nineteenth-century American taste and consumption, notably Sumpter Priddy’s American Fancy and David Jaffee’s marvelous study A New Nation of Goods.5 This exhibition and its attendant publication break new ground by emphasizing Porter’s role as a man who was above all else committed to bringing new ideas to the widest possible audience. If one leaves with an overwhelming impression of Porter’s aims, it is his lifelong pursuit to democratize information. As Sprague describes, “Porter promoted art among America’s burgeoning working and middle classes and pursued technological advancement as a way to achieve a better future.”6 Sprague and Wolff’s scholarship offers an important addition to the growing literature on nineteenth-century America’s visual and scientific evolutions and how new technologies changed social structures.7

The Bowdoin College Museum of Art, nestled within an idyllic liberal arts campus, is the ideal venue to present an exhibition that celebrates STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math) learning, albeit in nineteenth-century terms. True to the university art museum model, Rufus Porter’s Curious World is heavy on text, with nearly every object interpreted and section labels peppered throughout the show. The profusion of in-gallery writing allows for comprehensive assessments of objects and their connections to the exhibition’s themes. Labels also take pains to link Porter and his contributions to Bowdoin College’s history, an effort that reveals a few surprising confluences, but that can feel strained.

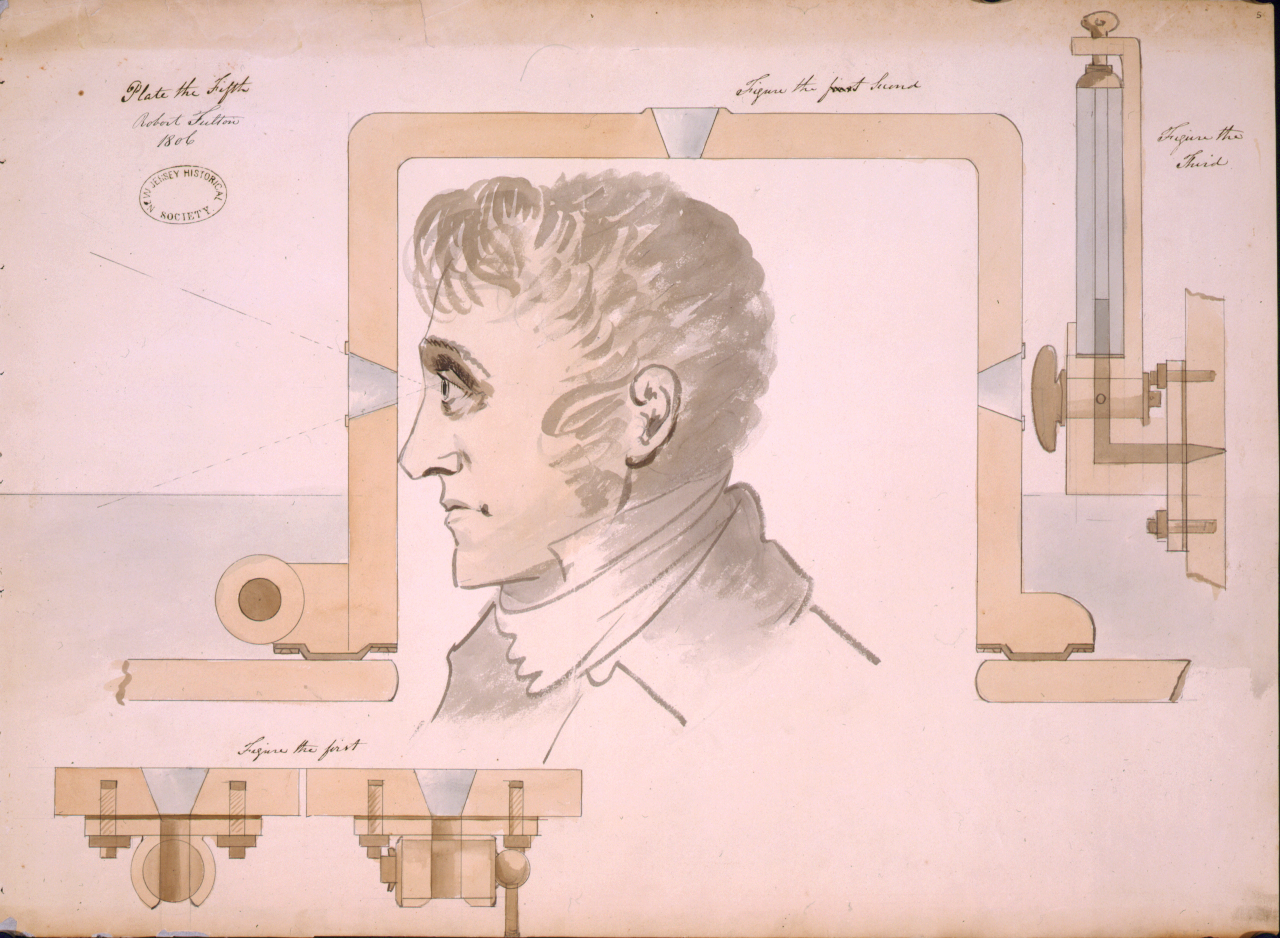

The show opens by introducing viewers to Enlightenment thought and its propagation in the United States (fig.1). Curators set out the stakes of their argument early, namely that Porter should be considered on a par with contemporaries such as Fulton and Morse. Benjamin West’s masterful portrait of Fulton in this section shows the inventor elegantly attired and seated in front of a drawn curtain. Beyond, West paints a maritime scene made lively by a bright burst of light: the detonation of an underwater torpedo. The torpedo was one of Fulton’s inventions, but the spray and sparkle close to the figure’s head also seem to visualize the eureka moment of a curious mind as it alights on a new idea. Fulton’s sketch for a periscope also hangs nearby (fig. 2). Somewhere between functional rendering and portrait, the watercolor and ink drawing exemplifies the artful depictions that men such as Fulton and Porter employed to bring their ideas to life.

The exhibition follows the young Porter from his rural Maine roots through his early career as an itinerant portraitist and miniaturist alongside other Maine-based artists such as John Brewster Jr. and William King. Curators thoughtfully include a painted drum to illustrate Porter’s role as a member of the Portland Light Infantry, a group who mustered at the base of the city’s Munjoy Hill. Painter Charles Codman’s Entertainment of the Boston Rifle Rangers by the Portland Rifle Club in Portland Harbor, August 12, 1829 (1830, Brooklyn Museum) illustrates the observatory at the apex of that hill, presenting a view that Porter would return to in his landscape murals. Charles Bird King’s 1830 painting The Itinerant Artist (Fenimore Museum of Art) anchors this section to help visitors imagine Porter’s work as a journeyman artist working in homes across New England.

This section and the next also offer the best opportunity to date to see miniatures attributed to Porter together in one place. Not only do these detailed paintings and silhouettes provide a lively account of au courant fashions, but the array also accentuates Porter’s precision and his use of optical devices such as a handmade camera lucida. Curators also include an advertisement for Boston’s Columbian Museum to remind us that what Porter lacked in formal education, he made up for in his interactions with like-minded artists, publishers, and thinkers through visits to centers of public learning. In a large case that is too deep to allow close inspection of individual objects, visitors may be able to pick out the first indication of what would became a lifelong occupation for Porter—the transmission of information in published books and pamphlets. Porter’s Revolving Almanack, an ingenious movable calendar, is on view and would make information graphics experts such as Edward Tufte swoon.8 This section also introduces visitors to Porter’s early and influential publication, A Select Collection of Valuable and Curious Arts. The manual for budding artists was replete with instructions on mixing pigments, creating optical devices, and fashioning dimensional effects with a brush. Although a modest object, Porter’s published recommendations had a wide impact on New England artists, providing mural painters, furniture decorators, and embroiderers with practical information. Unfortunately, curators have selected a single mourning embroidery and one Walter Corey chair to illustrate the use of Porter’s recommendations in the fine and decorative arts; their tableau feels spare in comparison to the rich array of works in the previous gallery and the wide influence of Porter’s ideas on art and material culture, particularly in New England.

The following sections highlight Porter’s inventions such as the percussion-cap revolving rifle, the patent for which Porter sold to Samuel Colt in 1836 for a paltry one hundred dollars.9 Also installed is a tall clock with mechanisms Porter designed that still keeps time. Its ticking creates a steady cadence in the gallery, an auditory reminder of the era’s pleasure in order and industry. Other inventions include a fire alarm system that Porter debuted in 1840 with a marvelous painted glass image of a house ablaze. The device stands out as yet another clever means by which Porter blended invention and artistry. This portion of the show also chronicles Porter’s career as a publisher and the evolution of what would become Scientific American. The original design for the magazine masthead encapsulates Porter’s lofty aims for the publication. We see a shrine of learning surrounded by new means of mass transportation connecting Americans over large distances, just as the magazine itself sought to do.

Luckily for visitors, the curators took on the considerable challenge of bringing an example of Porter’s fragile mural work to the galleries. Viewers can examine a large panel from a lively suite that Porter created for the Francis Howe home in West Dedham (now Westwood), Massachusetts (fig. 3). Unlike fellow muralists of the moment, such as Michele Felice Cornè, who illustrated European vistas in the parlors of his well-to-do American clientele, Porter painted familiar agrarian and coastal landscapes to bring the New England scenes into the homes of his patrons. A nearby touchscreen allows visitors to virtually tour the murals installed in their original positions and get a sense of how astutely he responded to the home’s architectural quirks in his designs.

The final portion of the exhibition unfortunately misses an opportunity to instantiate Porter’s most far-fetched but potentially transformative invention—a flying machine for cross-country travel during the California Gold Rush. Porter’s efforts to bring his “aeroport” into being unfold through cartoons lampooning the efforts and a series of letters between Porter and his principal investor, William Markhoe. In the correspondence, Porter makes increasingly desperate pleas and promises to secure funding for the ultimately unsuccessful project.10 Curators rely on enlarged reproductions of drawings and advertisements to present Porter’s invention but failed to utilize potential resources available at Bowdoin. The museum recently partnered with an on-campus lab to produce a 3D-printed Assyrian sculpture on view on the floor above, and such a collaboration between the arts and sciences might have yielded a model of Porter’s invention and put into practice the artistic and scientific synthesis that he championed.

Rufus Porter’s Curious World closes with a coda that poses but does not fully answer the question of why Porter never ascended into the pantheon of heralded nineteenth-century American inventors. A Currier and Ives print, The Century of Progress, features the technologies that made America, from Fulton’s steamboat to Morse’s telegraph. Sprague and Wolff posit that Porter and his inventions are excluded from such images because he failed to make his mark with one transformative idea and also because he was simply awful at business. This assessment is not entirely satisfying. Curators skirt, but do not address head on, the matter of class that also plays a role in the difficulties Porter encountered when compared to men such as Fulton and Morse. Morse descended from a well-known family of preachers and attended Phillips Academy and Yale University. Fulton married into wealth and spent time in Philadelphia before settling in rural Pennsylvania. Both traveled internationally to absorb and bring back ideas and influences from Europe that shaped their careers. Porter was a man of a different social sphere, who presented his ideas without the imprimatur of his better remembered compatriots. As Wolff describes in the catalogue, for instance, receiving patents relied as much on who one knew and how one worked the system as on the ingenuity of one’s invention. The playing field, in short, was not an even one.

The accompanying catalogue includes contributions by Sprague and Wolff and an additional essay on Porter’s miniatures by Deborah M. Child. The book is a handsome and important corollary to the exhibition. Sprague’s prodigious research situates Porter in his local and national milieu and details the surprisingly cosmopolitan worlds from which he emerged in New England. Figures such as Porter’s Maine neighbor, the printer Gardner Goold; Portland art historian John Neal; and the Bowen publishers of Boston overlap with Porter at opportune points to influence his thinking. Sprague’s biographical sketch makes a brief but tantalizing mention of a set of religious tracts that Porter published independently and as part of Scientific American. Her foray into Porter’s religiosity begs for more in-depth discussion and context. How did men of science such as Porter wrestle with their faiths in an age of reason? Child astutely surveys the published work on Porter to date, and provides a careful accounting of technique and patronage in Porter’s miniatures. Wolff situates Porter’s seemingly disparate contributions to the “useful arts” within a career-long interest in networks and social connections. As Wolff writes, “what Porter lacked in commercial success he compensated for with a farseeing vision for a networked nation, a country literally connected by transportation systems and metaphorically connected by shared, useful knowledge and the energy of vigorous optimism.”11 Like his subject, Wolff takes the aerial perspective and manages to locate a unifying thread between Porter’s seemingly disparate activities and passions.

The exhibition and catalogue bring much needed attention to an insatiably compelling nineteenth-century artist and inventor who has not gotten his due. Because of the COVID-19 epidemic, many students and visitors may sadly miss out on the chance to visit this show in person and to compare it to another long-anticipated exhibition organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture, in Washington, DC. That landmark display of the Prussian naturalist’s impact on American art and culture provides a fascinating companion exploration of the union of art and science in eighteenth and early nineteenth-century America.

The COVID-19 epidemic has caused social upheaval and forced isolation reaching far beyond the shuttering of exhibitions. We are estranged from one another in new ways, having severed connections that anchored our daily lives. Technology, despite Benjamin and MacLuhan’s warnings, is helping many of us alleviate some of that isolation. I take some solace in imagining what new tools Porter—a lifelong seeker of “useful knowledge” and a fervent advocate for linking people to information and to one another—might have devised to bring us together in these uncertain times.

Cite this article: Diana Jocelyn Greenwold, “Discovering the ‘Yankee Da Vinci,’”review of Rufus Porter’s Curious World: Art and Invention in America, 1815–1860, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10116.

PDF: Greenwold, Discovering the Yankee Da Vinci

Notes

- Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935; repr. London: Penguin Books Ltd. 2008); Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964; repr. London: Routledge Classics, 2008). ↵

- Scholars of New England painted interiors were the first to publish on Porter in the 1920s. See Edward B. Allen, Early American Wall Paintings, 1710–1850 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1926), 83–84; and Louise Karr, “Old Westwood Murals,” Antiques 9, no. 4 (April 1926): 231–36. ↵

- Jean Lipman, Rufus Porter, Yankee Wall Painter (Springfield, MA: Art in America, 1950); and Linda Carter Lefko and Jane E. Radcliffe, Folk Art Murals of the Rufus Porter School: New England Landscapes, 1825–1845 (Atglen, PA: Schiffer, 2011). ↵

- Jean Lipman, Rufus Porter: Yankee Pioneer (New York: C. N. Potter, 1968); and Jean Lipman, Rufus Porter Rediscovered: Artist Inventor Journalist (New York: C. N. Potter, 1980). ↵

- Sumpter Priddy, American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts, 1790–1840, exh. cat. (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Art Museum in association with the Chipstone Foundation, 2004); and David Jaffee, A New Nation of Goods: The Material Culture of Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011). ↵

- Laura Fecych Sprague and Justin Wolff, Rufus Porter’s Curious World: Art and Invention in America, 1815–1860, exh. cat. (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019), 9. ↵

- See Wendy Bellion, Citizen Spectator: Art, Illusion, and Visual Perception in Early National America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011); Peter John Brownlee, Samuel F. B. Morse’s “Gallery of the Louvre” and the Art of Invention, exh. cat. (New Haven, CT: Terra Foundation for American Art in association with Yale University Press, 2014); and Eleanor Harvey, Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture, exh. cat. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020). ↵

- Edward R. Tufte, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, 2nd ed. (Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press, 2001). ↵

- Herbert G. Houze, Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, and Carolyn C. Cooper, Samuel Colt: Arts, Art and Invention, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 294; and Sprague and Wolff, Rufus Porter’s Curious World, 36. ↵

- Historians such as Karen Halttunen, Neil Harris, and James W. Cook have documented the rise of confidence men and swindlers, men who put the nineteenth-century public on constant alert . We should understand Porter’s hyperbolic language and his repeated failures to gain investors’ trust as part of the learned skepticism of the age. See Neil Harris, Humbug; the Art of P. T. Barnum (Boston: Little, Brown, 1973); Karen Halttunen, Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830–1870 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986); and James W. Cook, The Arts of Deception: Playing with Fraud in the Age of Barnum (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001). ↵

- Sprague and Wolff, Rufus Porter’s Curious World, 82. ↵

About the Author(s): Diana Jocelyn Greenwold is Curator of American Art at the Portland Museum of Art, Maine