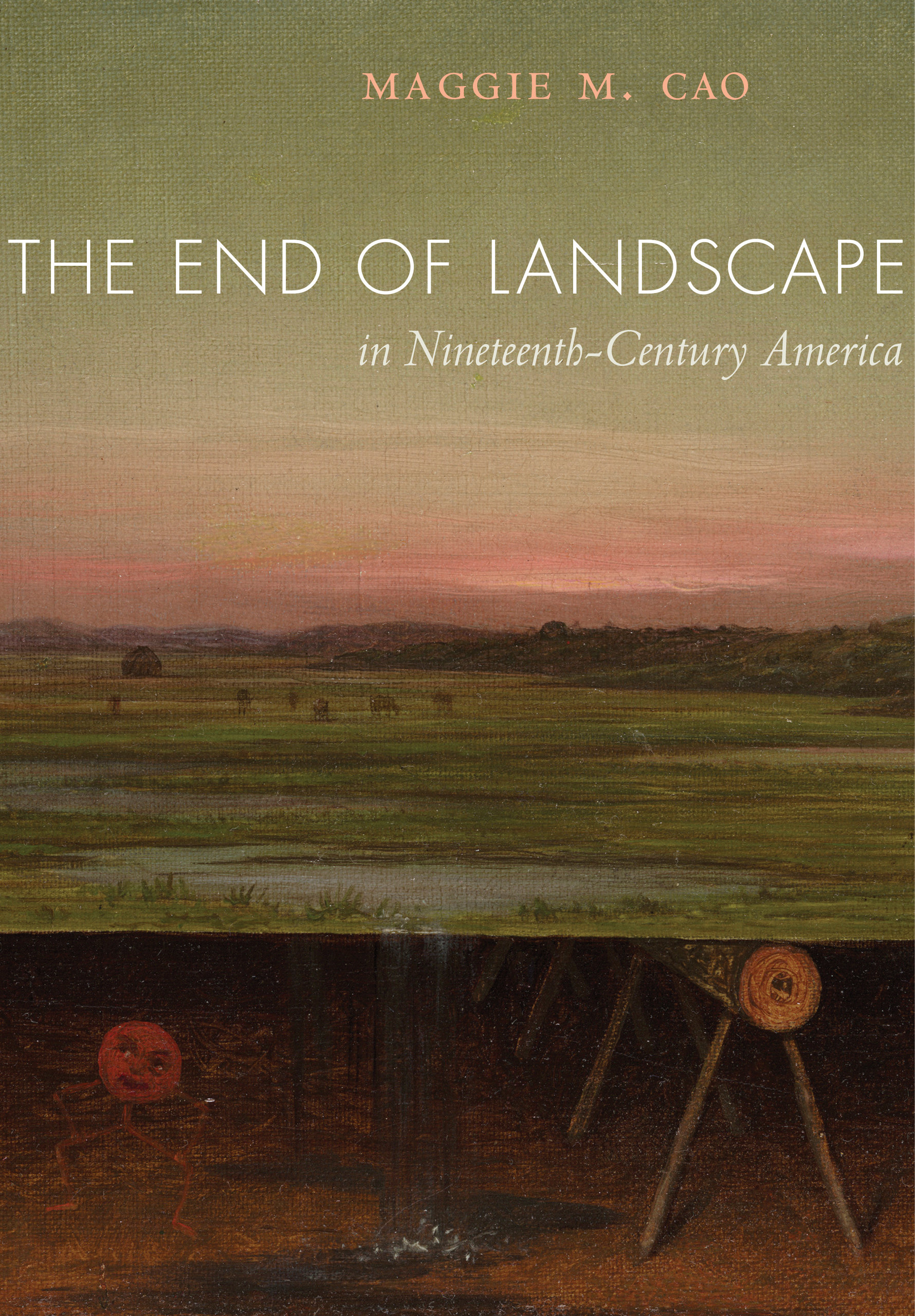

The End of Landscape in Nineteenth-Century America

Maggie M. Cao

Maggie M. Cao

Oakland: University of California Press, 2018. 280 pp.; 105 color illus. Hardcover: $65.00 (ISBN: 9780520291423)

In 1873, when Jervis McEntee complained that “my pictures accumulate on my hands and there seems no one to buy them,” he was grumbling, as usual, about his own economic anxieties, as he compared sales of his landscapes to those of some of his contemporaries, such as Frederic Edwin Church. He was also putting into words what must have been nagging at the minds of all American landscape painters in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, namely the precariousness of their genre in a rapidly changing world.1 Maggie Cao addresses this “end of landscape” in her exceptional book of the same title. In this volume, which combines agile prose, wide-ranging historical research, and surprising and thought-provoking images, Cao provides an account of the long and fraught dissolution of landscape painting in the face of modernity.

In the chronologically organized book, in four chapters that focus on the works of six artists, she argues that contemporary historical anxieties were manifest in the artists’ material practices, particularly in objects—such as butterflies formed by folding paper over wet paint or animal-shaped stencils placed on small landscape paintings—that were on the periphery of the landscape genre. Cao brings this extraordinary set of objects out of the shadows and applies keen visual analysis in order to uncover the ways in which the concerns of the age regarding the physical landscape and landscape painting erupted in art, language, scientific and technological experiments, and management of the land itself. Cao uses these objects—which she characterizes as “landscape experiments spanning five decades” (199)—as vehicles to understanding larger cultural shifts, such as Western expansion and the subdivision of land. Each chapter of the book pairs a broad contemporary concern about the land with a material practice that probes associated cultural anxieties.

Cao’s analysis departs from established scholarly emphasis within American landscape painting, which has either focused on the significance of the land depicted and featured the terrestrial in an effort to find symbolic meaning, or explored the intersection between social history and the landscape through investigations of tourism, imperialism, and scientific exploration.2 The artists were flexible about the equation between land and meaning, freely reworking plein air sketches in their New York studios whereby material practice could take precedence over accuracy. More recent studies in landscape have prioritized environmental and ecocritical concerns evident in nineteenth-century works.3 The End of Landscape gives both the material and the immaterial their due: investigating the meaning of the physical landscape, artistic practice, cultural discourse, and changing conditions of modernity.

Cao moves away from an analysis of the critical and economic reception that marked the decline in popularity of the genre in the late nineteenth century. Since many of the objects under consideration never entered the public arena, Cao instead suggests ways in which landscapists responded privately to the concerns of their age. In this study, the exceptional is used to explain larger themes. One of the notable attributes of the book is Cao’s ability to locate and recognize fascinating objects and to identify in them the importance of what might otherwise be dismissed as oddities. In her account, the objects are unified through their departure from convention, by artists whom she describes as standing out, standing alone, and going “too far” (6). Asking whether these artists were conscious of the anxieties that Cao argues are revealed in their practice is an impossible question, and one that she wisely does not try to answer.

In chapter one, “Closure: Albert Bierstadt’s Last Pictures,” Cao addresses the theme of closure as seen in small paintings of butterflies produced by Bierstadt beginning in the 1870s. Produced by folding pieces of cheap paper, and depending upon chance for their design, Bierstadt made these objects in a manner that was highly unlike his carefully composed, publicly exhibited large-scale canvases. Also unlike the large works, the butterflies circulated outside the financial market—they were presented as gifts in person and through correspondence. Cao uses the term closure and the idea of the fold to connect Bierstadt’s works both to the spatial compression of the West through the railroad and postal system and to the visual compression of the land and doubling through innovations such as stereo viewers. Her argument about the theme of folding incorporates other extraordinary mechanical innovations—such as Bierstadt’s design for a folding railway car, described in writing and drawing, and the stereo camera, cards, and viewer—along with the idea of chance in image making, concerns around specimen collecting, and cartographic depictions that mimic the shape of the butterfly and intersect with ideas of folding and spatial compression. In addition to these concrete technological developments, Cao points to more generalized spatial anxieties on national and individual scales and argues that in the performative aspect of the production of these objects, Bierstadt’s reenactment of “expansion in his unfolded butterflies circumvented his fears of closure” (63).

While chapter one addresses Bierstadt’s folding as a subliminal expression of anxieties about land closure, chapter two, “Sabotage: Martin Johnson Heade and Frederic Church,” is organized around the idea of sabotage. Cao explores the ways in which Heade’s pictures challenged the genre of landscape painting itself, as well as expressed concerns about environmental destruction. Although this chapter opens with a fantastic (but anomalous) composition that shows one of Heade’s own canvases as a dripping painting on an easel, below which there is a mischievous gremlin, Cao also looks at Heade’s more familiar images of tropical birds and flowers. She argues that Heade’s paintings emphasize the fragmentary nature of parts that also comprise Church’s compositions, creating parallels between the personal and professional relationship Heade had with the more successful (but younger) artist. Further, Cao proposes that the focus on the details (in opposition to the whole) and the body of the viewer are manifest both in Heade’s play with scale (the miniaturized landscape behind the birds and plants in the foreground), and in the lattice created by hummingbirds and branches. Through visual analysis, Cao argues that the foreground screen creates a rupture between planes by removing the middle ground, challenging the viewer’s navigation of the painting. She argues that Heade’s salt marsh paintings also present a landscape that is not traversable. It is literally soggy, empty of topographical interest, and resistant to contemporary reclamation projects. Heade’s work on both continents breaks down conventions of landscape and reassembles it in a way that calls attention to its construction, questioning the importance of the genre.

The commoditization of land through real estate development, as well as contemporary questions about the value of paper money, are addressed in chapter three, “Insolvency: Ralph Blakelock’s Economic Accretion.” Known only through a few examples and textual accounts, Blakelock’s small landscapes, or paper “currency,” were created on paper the size of banknotes toward the end of his life. He painted the landscapes in colors that resembled those used for paper currency and distributed them to friends and acquaintances. Investigating counterfeiting, trompe l’oeil still lifes, and the two-dimensional drawings created during real estate subdivision, Cao considers contemporary concerns around mimesis and systems of representation—both in artistic practice and the creation of paper money. Through analysis of Blakelock’s more conventional landscapes—nocturnes built up through a time-consuming process of repeated application of layers of paint—Cao connects both types of artistic production to growing modernist concerns about artist labor and the intersection of landscape (both actual and depicted) and economics. In her typically expansive manner, wherein she unites disparate elements around a single concept, Cao discusses such far-reaching ideas as hoarding, fetishization, and silhouette production. Through this investigation, she locates Blakelock’s interest in economics not only in his own financial worries following his institutionalization and precarious economic situation, but also around larger cultural anxieties about landscape painting and the physical landscape. In the end, these concerns are ironically reflected in the counterfeiting of his own works by others.

The last chapter of the book, “Camouflage: Abbott Henderson Thayer and John Singer Sargent,” studies these two artists and their work with camouflage not only as it intersects with Darwinian theory but also as it relates to modernity in artistic practice, psychology, and warfare. Cao reads the pictures of both artists as transforming the connection between the figure and the landscape, and she features the latter through an organizational approach that reflects the compositional claims she makes. She describes how the figure is hidden in a landscape in Thayer’s work, while background and foreground are reversed in Sargent’s paintings. Cao points to the way in which Thayer explores the figure-ground relationship through “disfiguring” or “landscaping”—changing a figure into landscape through camouflage. Although Thayer’s paintings, book illustrations, and scientific investigations have been well documented, Cao also discusses at length other kinds of objects, including his “bird skin landscapes” (made using the feathers and skins of birds), collages of photographs, and stencils. Sharing with Thayer an investigation of the relationship of the figure to the landscape, Sargent created images that enact “foreground-background inversions” (189). In his post-1900 landscapes, he experimented with perspective and form, giving landscape elements the appearance of figural forms and camouflaging figural forms through their depiction as landscape-like elements. By bringing this to the fore, Cao highlights the way in which the pictorial inversions in the work of both artists become a game of hide-and-seek for the viewer and also intersect with modernist aesthetics and concerns about space and subjectivity.

In The End of Landscape, Cao presents an extraordinary set of objects and carefully engages with the practices of these artists and the materiality of these particular works. Her astute visual analyses facilitate new ways of looking at familiar artists. From insightful discussions of the visual oddities of canonical works, such as Heade’s bird and flower subjects, to the unearthing of Blakelock’s currency, Bierstadt’s butterflies, and Thayer’s stencils, this book is a welcome addition to the literature on American art. In her conclusion, she describes art as “un-landed,” a concept that also characterizes her methodological approach. Throughout, Cao considers form and subject independently and yet weaves the two elements of each object together into a complex tapestry that includes the artist’s biography, general cultural concerns, historical and cultural developments, and technological innovations. Using richly evocative language, Cao’s book mirrors that of the objects she studies, joining its material form with unusual content and larger cultural meanings. In this manner, she shifts the ways in which landscape painting of the nineteenth century will be considered in the future and certainly puts to rest the notion that landscape painting merely “ended quietly” in 1875.

Cite this article: Melissa Geisler Trafton, review of The End of Landscape in Nineteenth-Century America, by Maggie M. Cao, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2245.

PDF: Trafton, review of The End of Landscape

Notes

- Jervis McEntee’s diary entry for May 21, 1873, as cited in Garrett McCoy, “Jervis McEntee’s Diary,” Archives of American Art 8, nos. 3/4 (July–October 1968): 20. ↵

- An excellent summary of the scholarship of American landscape (and more complete than can be recounted here) can be found in Cao’s own 2017 text: Ross Barrett and Maggie Cao, “Landscape in American History: Pasts, Presents, and Futures,” American Art 31, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 32–34. ↵

- See, for example, Karl Kusserow and Alan C. Braddock, eds. Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment (New Haven: Princeton University Art Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2018). ↵

About the Author(s): Melissa Geisler Trafton is Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of Visual Arts at the College of the Holy Cross