“The Sunflower’s Bloom of Women’s Equality”: New Contexts for Mary Cassatt’s La Femme au tournesol

In a 1913 article for the Philadelphia Inquirer, an unnamed critic fumbles awkwardly with a description of a painting by Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) (fig. 1). “She gives us here a scientific solution of a difficult problem—a light interior with reflections and juxtapositions of extraordinarily daring color,” the critic begins. “It is one of those canvases which shows more determination than of unconscious grace, and the result seems to have been arrived at through knowledge rather than inspiration. It is interesting in its uncompromising decisiveness, but is of an austerity which has never charmed the general public.”1 Failing to coalesce into any meaningful commentary, such a collection of words leaves the reader unsure as to whether the painting and its maker are a subject of scorn or esteem. Decisive, daring, austere, lacking in charm, a “scientific” solution to a problem: such a description is more befitting of the geometric abstractions of Analytic Cubism, which would flourish just a few short years after Cassatt completed La Femme au tournesol (Woman with a Sunflower).

In this painting from around 1905, Cassatt pairs a young woman, dressed in a shimmering yellow and green negligée, with a naked child seated in her lap. A wall mirror, painted in a loose hand, hangs behind them, doubling but also obfuscating the pair. The woman’s left hand gently braces the child’s shoulder as they gaze together into a small hand mirror. The mirror’s circular pane is filled with the child’s face, her rosebud lips and dappled cheeks slightly incongruous with her serious gaze, which refracts out to meet that of the viewer. Behind the child’s back—in linear alignment with her reflection and her head—a radiant sunflower is pinned over the woman’s heart, its petals unfurling and swelling. The flower forms the third point of a triangle with the child’s reflection and the woman’s face. One of the painting’s earliest mentions in print, the Inquirer description is an unfortunate augury for what was to come in the painting’s critical history.2 Despite its innovative composition and placement in what is arguably the most significant public collection of Cassatt’s work—the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC—La Femme au tournesol has been somewhat overlooked in critical scholarship, dismissed as yet another saccharine or even banal mother-and-child painting, merely one repetition among hundreds in Cassatt’s oeuvre.

In the few instances in which it has been subjected to closer scrutiny, the results have been less than favorable. Harriet Chessman calls it a “powerful and disturbing” painting, a meditation on the pitfalls of bourgeois femininity in which the child is severed from her own self-image. By offering her access to the hand mirror, the woman—assumed by Chessman to be the child’s mother—is complicit in this violence, as she “engages in an ongoing discourse of substitution, through which an actual body of an actual girl becomes subsumed in a series of representations.”3 Perhaps catalyzed by the presence of the double mirror, the painting seems to be a lightning rod for this kind of psychoanalytic commentary. Linda Nochlin, for example, describes it as paradigmatic of Cassatt’s “passionate devotion to the nude child’s body.” Desire, Nochlin asserts, is the operative force in Cassatt’s painting: “One might almost speak of Cassatt’s lust for baby flesh,” she writes, “a desire kept carefully in control by formal strategies and a certain emotional diffidence: in some cases, the less successful ones, displaced and oversweetened as sentimentality.”4

Griselda Pollock similarly fixates on the child’s nudity, though she moves away from the psychoanalytic in favor of a more allegorical reading about social constructs of femininity. Resisting assigning a maternal relationship to the figural pair (a point to which I will return), Pollock interprets La Femme au tournesol as a study of a kind of generation gap, wherein the woman—fashionably dressed and with finely coiffed hair—stands for a socially acceptable, restricted notion of femininity, while the child, in her naked, unfettered state of reflection, represents the potential to question and subvert that form of femininity.5 Pollock relies on the woman’s clothing—a “costume of the adult masquerade of fashionable femininity”—as evidence for her condemnation of the figure, and yet she misidentifies the woman’s garb as a gown or dress, when it is actually a negligée or peignoir. The garment’s low, scooped neckline and flowing sleeves are much more consistent with turn-of-the-century fashions in nightgowns than with dresses suitable for public wear.6 While it may still be understood as fashion-forward, the reidentification of the model’s dress as a private, intimate garment undermines arguments like Pollock’s, which hold the figure to be a symbol of performative, bourgeois gender; though hardly subversive, the peignoir categorizes the painting as a private scene rather than a public one. Moreover, though her interpretation leans heavily upon her understanding of the woman’s attire, Pollock entirely ignores the garment’s most prominent feature: the sunflower.

Despite its compositional centrality, the sunflower has proven recalcitrant as an interpretive element. More often than not, it has gone unremarked on in the few critical discussions of the painting. When not dismissed outright as mere ornament, the sunflower has been taken by scholars and critics as a sort of sublimated sexual symbol, an emblem of “female fecundity,” in the words of one review.7 A 1980 catalogue entry describes it clumsily, jostling between its formal qualities and a halfhearted attempt to ascribe to it a connotation of organic abundance: “The sunflower is an unusual motif, and it spreads its golden summer light throughout the painting, played against green, the other color of growth.” Following a description of the figures’ “rotundity,” the entry continues, “As in nature, there are already signs of inevitable decay amid the fecundity,” gesturing to the degradation of Cassatt’s eyesight in the decades that followed by critiquing her handling of the figures’ hands.8 In her catalogue essay for the landmark exhibition Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman (1998–99), Judith Barter mercifully refigures such vague suggestions in more concrete terms. Looking to the long tradition of flower symbology in Christian image making, Barter calls upon the sunflower’s emblematic association with the Madonna to clarify the nebulous association of the painting with female fertility.9

While the instinct to examine the iconographic associations of the sunflower is a good one, Barter fails to consider its specific resonance in Cassatt’s own lifetime. By turning our critical gaze to the painting’s focal point and restoring its historical specificity, a new interpretation of La Femme au tournesol begins to emerge. Far from a symbol of restrictive, retrograde femininity (or essentialist fertility), the sunflower and its bearer are beacons of Cassatt’s fervent feminism, a latent symbolism that emerges when the painting is considered within the context of the American suffrage movement.

In 1867, the sunflower was adopted as the official symbol of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), a way of honoring the (unsuccessful) bid for women’s right to vote in Kansas—the Sunflower State. A notice in an 1887 edition of the Woman’s Journal invokes not the sunflower’s association with the Virgin Mary but instead the progressive poetics of its natural heliotropism: “The woman suffragists of Kansas lately adopted a yellow ribbon as their distinctive sign. They call it the ‘sunflower badge.’ They say they chose it ‘because, as the sunflower follows civilization, follows the wheel-track and the plow, so woman suffrage inevitably follows civilized government.”10 The published proceedings of NAWSA’s twenty-eighth annual convention in 1896 bore a sunflower insignia on its title page (fig. 2) and included a speech given by a delegate from South Carolina entitled, “The Sunflower’s Bloom of Woman’s Equality.”11

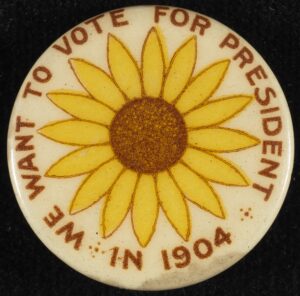

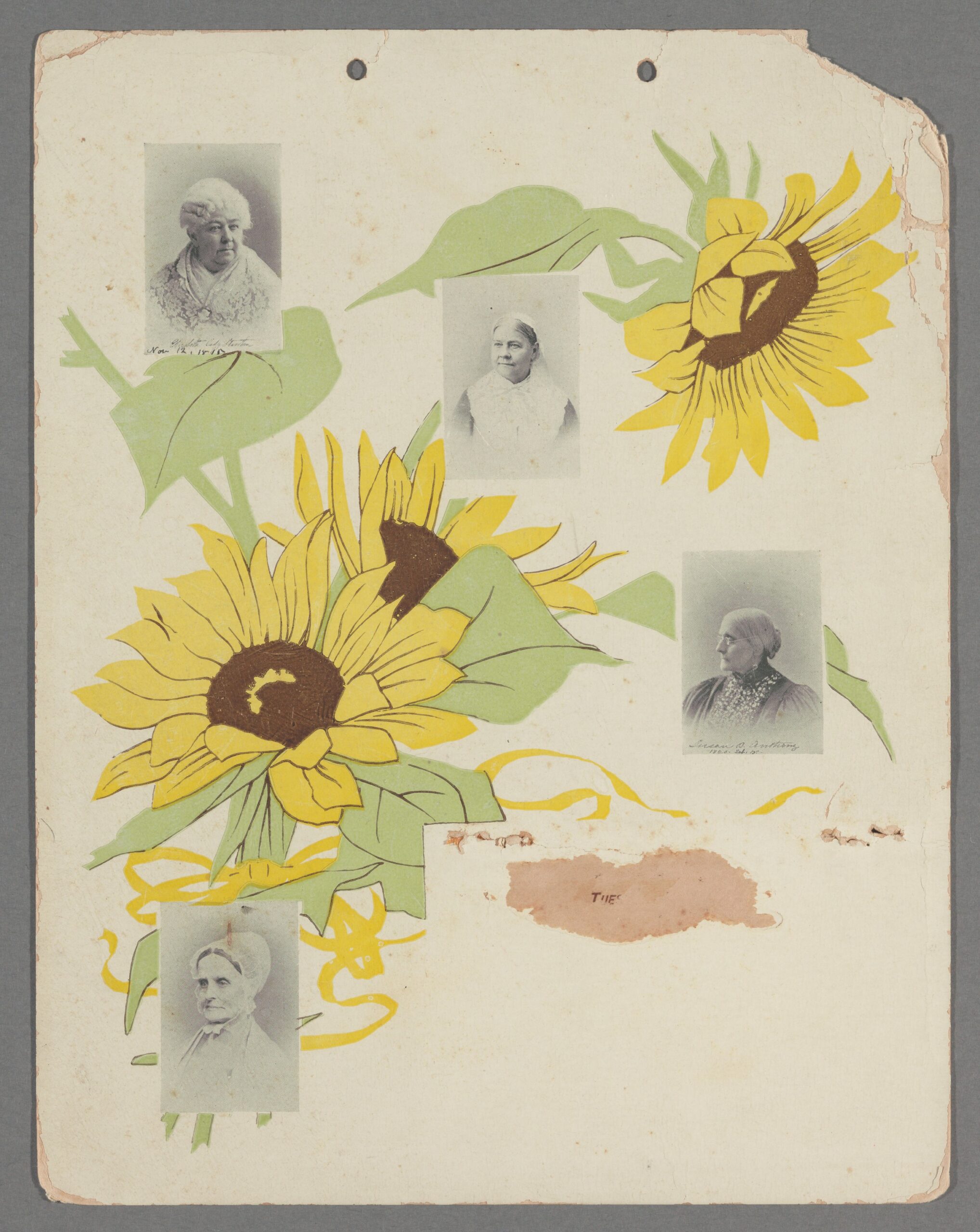

Beyond internal materials, the sunflower also came to be associated with the suffrage movement in popular visual and material culture. As Margaret Finnegan has studied in detail, activists were keenly aware of the power of consumer culture and its role in shaping public discourse.12 As such, NAWSA produced a number of buttons, stickpins, and other wearable commodities featuring the suffrage sunflower. One such badge bears the slogan “VOTES FOR WOMEN” adjoined to a fabric sunflower, identifiable by its color and characteristic layered petals (fig. 3). Cassatt’s painted sunflower reads like a surrogate for just such an accessory, pinned over her model’s heart much as the badge would be to an activist’s chest. Another pin hosts a simplified rendering of a sunflower at center, ringed by the clarion call, “WE WANT TO VOTE FOR PRESIDENT IN 1904”—just one year before Cassatt painted La Femme au tournesol (fig. 4). An ephemeral print now held by the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Radcliffe Institute (fig. 5) embeds photographic portraits of American suffrage leaders among effulgent sunflower blossoms.13 By the turn of the century, the sunflower and its distinctive golden color were deeply embedded within the popular visual vocabulary of the American women’s suffrage movement.14

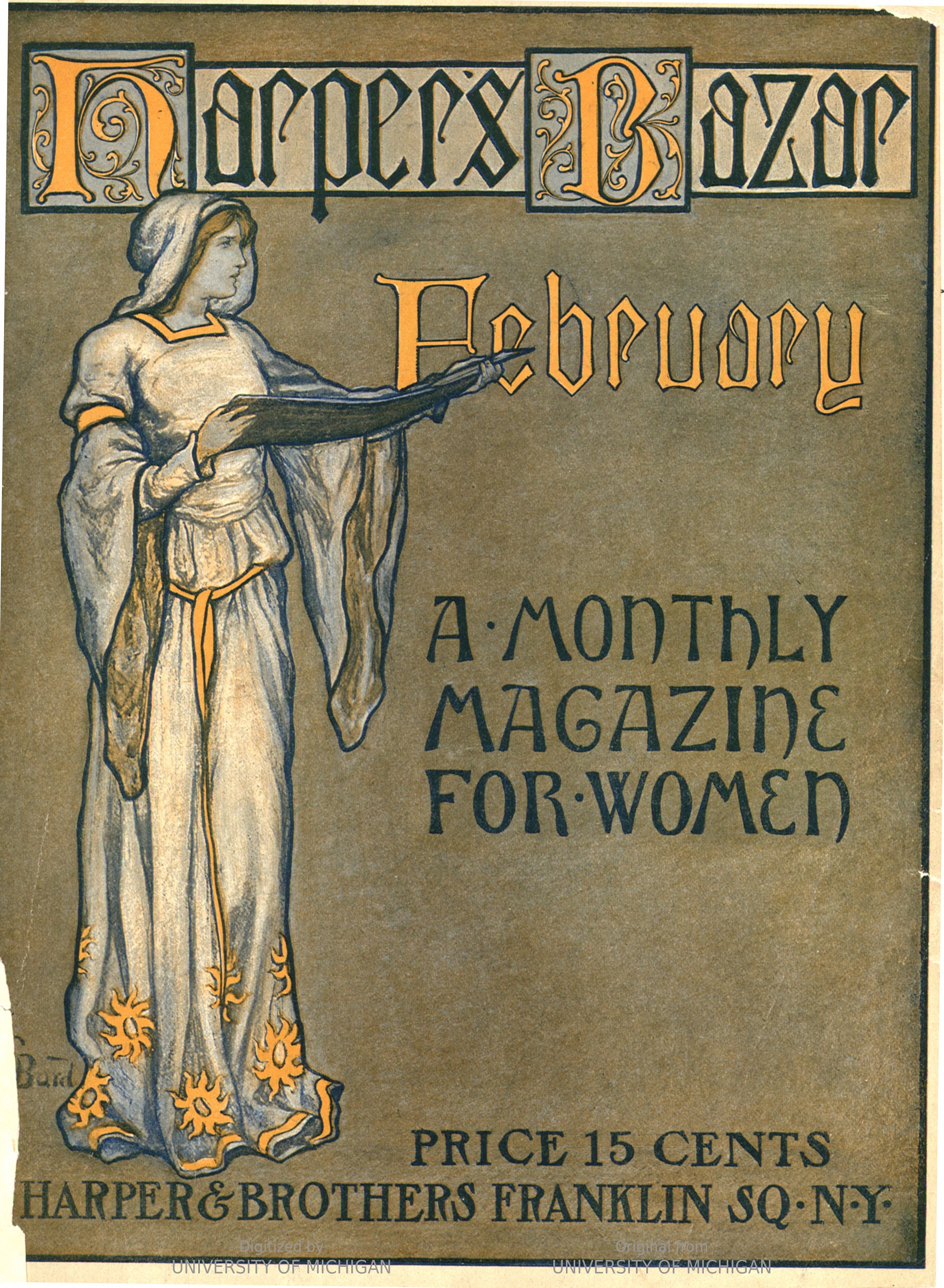

There can be little doubt that Cassatt was aware of the sunflower’s significance to the suffrage cause when she centered it so prominently in her painting. In the years following La Femme au tournesol’s completion, Cassatt wrote prolifically about the importance of gender equality and the right to vote. Though she had lived permanently in France since the 1870s, her engagement with feminist thought and movements was largely in an American context. Louisine Havemeyer (1855–1929), her closest friend and interlocutor, was an active and highly visible member of the suffrage movement; at one point she was even arrested for her participation in a protest action for the cause. Cassatt got her news primarily from the American press, regularly reading the Paris Herald Tribune (the European edition of the New York Herald Tribune, now the international edition of the New York Times).15 There is also evidence to suggest that Cassatt engaged with American publications geared toward women, such as Harper’s Bazar, which frequently featured articles on prominent leaders of the suffrage movement (as well as on Cassatt herself). Indeed, there is a striking resemblance between the flowing negligée worn by the model in La Femme au tournesol and an illustration on the cover of the February 1905 edition of Harper’s, which featured a stylized medieval woman (perhaps a priestess) donning a robe with a similarly draped sleeve, embellished with blazing yellow suns (fig. 6).16

Despite an overwhelming body of primary archival evidence documenting her devotion to the cause of suffrage and her strident belief in gender equality, there remains a scholarly aversion to calling Cassatt a feminist. Even if we lack a letter or written account of Cassatt overtly describing herself as such, the term itself is hardly anachronistic, especially given its prevalence in French women’s movements at the time, with which Cassatt would have been familiar.17 Of course, Cassatt’s feminism is necessarily circumscribed by her historical position: an upper-class white woman at the turn of the century, she was largely unconcerned with the plight of the working class and, as far as the extant historical record shows, unaware of the parallel activism and struggles of Black women in her time.18 Such limitations, however, should not stand in the way of articulating what was a meaningful political and ethical force for Cassatt; indeed, much of the critical rhetoric that has curtailed our understanding of Cassatt’s feminism says more about the internalized misogyny of the present than the shortcomings of the past.

In a review of Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman—the most recent monographic exhibition of Cassatt in the United States—one critic praised the curator, Judith Barter, for qualifying Cassatt’s feminism as “emerging” and “of a nineteenth-century variety,” as if it could be of any other time. He continues, quoting Barter’s definition of this brand of feminism: “‘What this means is that women felt that they should have the authority and the power to instill the moral values that were necessary in their children.’ In other words, Cassatt was no bra-burner.”19 Putting aside the critic’s trivialization of feminism writ large, the delimitation of Cassatt’s feminism as one that is concerned solely with the role of mothers in child-rearing is a profound erasure of her devotion to women’s rights. In fact, while the archival record of Cassatt’s feminism is practically silent on the question of motherhood or other family issues,20 Cassatt frequently expressed her concern for women’s rights within the context of global politics, crystallizing around the advent of the First World War. Having been forced from her home at Beaufresne in the summer of 1914 by the advancement of German troops, Cassatt wrote with urgency to Havemeyer of the geopolitical exigency of women’s suffrage. “When will the world grow more civilized?” she wrote in December 1914; “Will it be when women vote? I hope so.”21 A letter from Cassatt in that same year transcribed in Havemeyer’s memoir employs even more forceful phrasing:

Of course every question is subordinated to the war, but never more than now was suffrage for women the question of the day,—the hope of the future. Surely, surely! Women will wake to a sense of their duty and insist upon passing upon such subjects as war, insist upon a voice in the world’s government.22

Whether or not she conflagrated her undergarments, Cassatt’s feminism was clearly one that looked beyond the walls of the home and the duties of motherhood. Overlooked as conventionally sentimental or otherwise disdained as an image of bygone femininity, La Femme au tournesol is a monument to our scholastic failure to relinquish our hold on fundamental assumptions about the political potential of “feminine” artistic practices. Recognizing the iconographical source of the sunflower in the American suffrage movement allows us to reconsider Cassatt’s painting entirely.

Examining her career more broadly, we can see evidence of Cassatt’s feminism not only in her use of suffragist iconography but also in her strategies for exhibition and circulation. La Femme au tournesol was among the twenty-nine works by Cassatt that hung in a 1915 exhibition organized by Havemeyer, the Loan Exhibition of Masterpieces by Old and Modern Painters, staged at the Knoedler Gallery in New York.23 The exhibition’s innocuous title obscures its vital purpose, namely to raise funds for the suffrage cause. Proceeds from the exhibit, garnered from entry fees, founded the Woman Suffrage Campaign Fund, fulfilling Havemeyer’s desire that her art collection “take part in the suffrage campaign.”24 Correspondence between Havemeyer and Cassatt in the year leading up to the exhibition makes clear Cassatt’s involvement and investment in the exhibition as a collaborator and advisor. While Havemeyer’s original concept was a monographic exhibition of the work of Edgar Degas (1834–1917), she developed the idea further to include Cassatt’s work as well. Despite some initial reluctance, Cassatt was eventually persuaded to participate by the promise of promoting the suffrage cause. She wrote to Havemeyer in May 1914 to acquiesce: “As to an exhibition of my work in New York you know how I feel about the, to me, question of the day. If such an exhibition is to take place, I wish it to be for the cause of woman suffrage. In that case I will send over the few things of mine I own.”25 From that point on, Cassatt was integral in helping the exhibition take shape, writing letters on Havemeyer’s behalf to arrange for further private loans and generally acting in an advisory capacity.

In its final form, the exhibition consisted of a central gallery featuring the work of Degas and Cassatt, flanked by two smaller galleries devoted to the work of the Old Masters, including Johannes Vermeer, Rembrandt van Rijn, Peter Paul Rubens, and others.26 While, at first glance, the contents of the exhibition do not seem to bear a suffragist subtext, Ruth Iskin has argued convincingly that Havemeyer’s aims were beyond the fiduciary support of the cause. Her ambition, Iskin writes, was to present Degas and Cassatt as equals, “thus embodying a feminist message of gender equality in the exhibition that supported women’s suffrage, and demonstrating the continuity between the Old Masters and modern painters.”27 Iskin’s point is well taken; Cassatt’s frequent misidentification as a student or follower of Degas thoroughly vexed her, and the chance to be seen on equal footing would have appealed to both women.28 One month before the exhibition opened, Cassatt reflected in a letter to Havemeyer, “I am surprised at the coolness I show in exhibiting with Degas alone, but one thing Louie I can show, that I don’t copy him in the age of copying. I cannot open a catalogue without seeing stealings from me.”29 For her part, Havemeyer had no problem stating this outright. In the opening lines of her lecture on Degas and Cassatt, delivered on the day of the exhibition’s debut, Havemeyer put the matter plainly when describing the trajectory of the artists’ relationship: “She could do without him, while he needed her honest criticism and her generous admiration.”30 Both women understood the role that art could play in the sociopolitical sphere, even if its contents were seemingly free of feminist messages.31

In addition to its inclusion at the Knoedler exhibition and its invocation of the visual vocabulary of the suffrage movement, there is further evidence to suggest that Cassatt understood the inherent political power of La Femme au tournesol. A closely related painting (fig. 7)—linked indelibly by the appearance of the distinctive peignoir—tells yet another story of Cassatt leveraging her profession to political ends. The tondo was one of three for which Cassatt accepted a commission in 1905 for the Ladies’ Lounge at the newly erected Pennsylvania statehouse in Harrisburg.32 Cassatt would complete only two of the promised paintings, neither of which would ever be delivered, as she withdrew her works under dubious circumstances. After accepting the commission, Cassatt was approached by a local politician who demanded a kickback of half of her payment.33 According to a 1910 newspaper item, this was but one instance of corruption in a larger “capitol ring” that surrounded the construction of the statehouse.34

The visual proximity of the La Femme au tournesol to the Harrisburg tondo not only suggests that Cassatt was thinking about a political context for her works (in the most literal sense) at the time of their creation but further indicates that she was actively considering the political capital of her paintings. Pulling the commission was both an act of financial self-preservation as well as a moral stand against the corruption that she detected within the capitol building project. Regardless of subject or style, Cassatt understood how her work and reputation lent her significant cultural capital; withholding her name and her paintings was one way to enact that power in the political sphere of her home state.

This is not to say that the content of Cassatt’s works themselves should not be considered politically potent. Indeed, the assumption that her primary subject—the lives of women—is not inherently political hews to retrograde ideas about gender, domesticity, and their interpretive limitations. Moreover, Cassatt’s return in her later years to the formal language of figural realism has long since been written off as a retreat, as if the style itself signaled a latent conservatism. Suspending these assumptions opens up a more generous understanding of the political bent of Cassatt’s work, one that more accurately aligns with her own politics. Cassatt’s great talent was her proclivity for relaying radical ideas via a seemingly anodyne visual vocabulary; in other words, Cassatt used the inoffensive imagery of women and children—appropriate subjects for a woman of her class—as cover for her works’ feminist connotations. Nowhere is this clearer than in yet another public commission, the Modern Woman triptych that Cassatt made for the Woman’s Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (fig. 8).

From its inception, the Woman’s Building was a politicized sphere, openly declaring itself as a space dedicated to both the past accomplishments and future flourishing of women. An early statement from its organizing body, the Board of Lady Managers, boldly set out the building’s aim to illustrate that women “were the originators of most of the industrial arts, and that it was not until these became lucrative that they were appropriated by men, and women pushed aside.”35 For her part, Cassatt’s contribution to the Woman’s Building’s Hall of Honor was an allegory for the cultivation and sharing of knowledge between generations of women. Reimagining the biblical tale of Eve’s temptation, in which she is lauded rather than condemned for partaking of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, Cassatt paints a harmonious scene of labor and the pursuit of success, in which women work together to support one another in their mutual endeavors. In her study of the mural and its iconography, Sally Webster describes Modern Woman as “a transgressive interpretation of the Genesis legend,” cloaked in a “genteel manner.”36 The Chicago mural represents a major turning point in Cassatt’s career, not least because it inaugurated a motif in her artistic practice that would continue until her death, namely her appropriation of biblical and Marian imagery. Referred to by scholars as her “modern Madonnas,” Cassatt’s late works frequently participate in the broader trend among turn-of-the-century feminists of retooling Judeo-Christian iconography for their own progressive purposes.37 In this light, Barter’s interpretation of the titular sunflower in La Femme au tournesol as an emblem of the Madonna is fitting and not at all at odds with the radical connotations of its suffragist context.38

Cassatt’s ability to leverage seemingly conventional imagery to progressive aims did not go unnoticed in her lifetime. Warding off the assignment of conservatism to her late figural style, the critic Roger Marx (1859–1913) pointed to evidence of Cassatt’s “profound study of the Old Masters,” as well as her fruitful “interpretation of the modern ideal.” Cassatt’s work, Marx writes, is subtle and progressive; it possesses a:

value all its own. . . . The arrangement, the distribution of masses and balance of lines give her work the stamp which characterizes the creations we are wont to term nowadays classical. Let us hasten to add that while holding to the rules which guided the masters, she transforms their tradition by revivifying it.39

Marx’s admiration for Cassatt was reciprocated; in 1902, she wrote to Havemeyer, “When one gets with the right person talking Art is pleasant as we know. I wish you knew Roger Marx[;] you must meet him.”40 The two enjoyed a fruitful friendship and correspondence until Marx’s death in 1913. Marx wrote robustly on the social and political potential of art and worked both as a critic and a museum professional (having been named the inspecteur général des musées départementaux in 1899). He is best remembered for his concept of art social, which held that artists could improve the lives of others through their work and that art could provide a space of healing and growth.41 Harmony and beauty, he asserted, were not merely secondary needs but were instead “the sign by which the desires of instinct and the progress of civilization are affirmed.”42 Significantly, Marx insisted that this category of art social not be restricted based on class—in the sense of neither a class of people nor of objects.43

Marx was one of the most vocal proponents of utopian aesthetics at the turn of the century, and his ideas clearly took hold of Cassatt. Their correspondence is rife with exchanges about the nature of art, especially as it pertained to women. Despite his progressive views about art and class, Marx was party to the sexism of his era, though that did not stand in the way of his open admiration for both Cassatt and Berthe Morisot.44 In a letter from around 1910, Cassatt upbraids him for suggesting that she take part in an exhibition of women artists, something that she categorically refused to do throughout her lifetime. With her frustration palpable, she writes, “Men have never refused women artists their share in exhibitions or in awards, now we want to separate them? How can you approve of this? No, in art, at least, men and women are on equal footing, at least as regards appearing before the Public.” Cassatt then goes on to revive a thread from previous correspondence: that women had not yet achieved greatness in visual art. Morisot and Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, she continues, are the great exceptions to that rule, and if either were still alive, they would surely agree with Cassatt’s reasoning.45 Though her assertion that equal opportunities had been presented to women by their male counterparts now reads as overly optimistic, her insistence on being judged on “equal footing” rather than by metrics determined by her gender demonstrates the importance Cassatt placed on gender equity in her professional life as well as in the political sphere. Given their robust exchange on the social dimensions of art, it is perhaps unsurprising that Marx would be the first owner of La Femme au tournesol, Cassatt’s homage to the political movement closest to her heart.

The circumstances of Marx’s acquisition of the painting are murky, archivally speaking. While some scholars suggest that he bought it via the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, it is more likely that he purchased it directly from the artist herself. Collection records indicate that the Cassatts acquired by Marx via gallerists were primarily prints, including an impression of In the Omnibus (1890–91) from Durand-Ruel.46 His archive is unfortunately silent on the matter of how and exactly when he acquired La Femme au tournesol; a letter between Cassatt and Marx, however, may provide a clue. In July 1906, Cassatt wrote to Marx from her home at Beaufresne: “I would be very happy if you can come visit in September, and I will answer all of your questions about my painting.”47 Though she could conceivably be referring to another work or even her practice in general (she elects the word peinture here rather than tableau, the former lending itself to ambiguity), the proximity of the letter’s date to the time that she was working on La Femme au tournesol allows for a degree of confident speculation. What is certain is that Marx was in possession of the painting by 1908, when it had its public debut at the Galerie Durand-Ruel, appearing under the title Le Miroir.48

Titles have proved challenging in Cassatt’s oeuvre at large, her works often taking on vague descriptive titles such as Mother and Child.49 La Femme au tournesol is perhaps the perfect case study; the painting has gone by multiple names in French and English, to say nothing of the myriad translations outside of Cassatt’s primary languages. Their development over time tells the story of the critical history of Cassatt, a cautionary tale about the interpretive proscription that can occur when titles saddle historians and the general public with a certain set of assumptions. In the case of La Femme au tournesol, a brief review of its capricious naming history reveals that its title was, at least partially, responsible for the erasure of its feminist undertones.

From the painting’s accession in 1963 until February 2019, the National Gallery of Art’s official title for it was Mother and Child, a title that was never used in an official capacity (that is, in either sales or exhibition catalogues) during Cassatt’s lifetime.50 The title I prefer here—La Femme au tournesol—is taken from the first record of sale for the painting, the 1914 sale of Marx’s collection following his death.51 Given that Cassatt was alive and in contact with Marx throughout his period of stewardship of the painting, it stands to reason that she would have had some say in the title that it went by.52 Moreover, it would retain this title through its next sale in 1930, following the death of none other than Cassatt’s friend Havemeyer, who had bought the painting from the Marx sale.53 Again, considering the intimacy and professional camaraderie enjoyed by the two women, it is safe to assume that Havemeyer would have used a title that was sanctioned by the artist.

From the sale of the Havemeyer estate, the painting was then acquired by the American banker and prolific art collector Chester Dale, who went on to bequeath his collection to the NGA in 1963. An official inventory of the Dale collection undertaken the following year lists the painting as La Femme au tournesol—Le Miroir (Woman with Sunflower).54 It is at this point—the transfer of stewardship to the NGA—that this title was obliterated. A copy of the same inventory page that lives in the museum’s object file renders this change visible: a handwritten notation amends the title to include “Mother and Child.” Another document, written in the same hand, repeats this gesture, this time scratching out “Woman with Sunflower” and adding the new title below.55 Following the NGA’s acquisition, the painting would be exhibited exclusively under the title Mother and Child.56

Yet another document in the NGA’s curatorial records proves illuminating on the question of the title change. In July 1968, the renowned Cassatt scholar Adelyn Dohme Breeskin wrote to John Bullard, then a member of the NGA curatorial staff, seemingly in response to his inquiries about the Dale Cassatts. After confirming dates for a number of other paintings, she writes, “Then if you could consider calling the c. 1905 painting ‘Mother with a Sunflower on her Dress’ as a translation of ‘Femme au tournesol’—it would certainly be definitive.”57 Breeskin, who would go on to publish the first catalogue raisonné of Cassatt’s paintings in 1970 (in which she identifies the painting according to her recommendation here to Bullard), inadvertently points to two challenges. The first is linguistic; the French preposition “à,” upon which the French title hinges (appearing here as “au,” a compound with the masculine definite article), is notoriously ambiguous and difficult to translate. Typically rendered as “at” or “to,” the preposition can also indicate possession; none of these options work particularly well in the syntax of the painting’s title. It is for this reason that I have retained the French title throughout the present article. Given her letter to Bullard, we can assume that Breeskin had similar issues in granting the painting a name in English, leading to the compromise of naming the sunflower as an ornament to the model’s dress, which is an accurate visual description, if a bit cumbersome as titles go: Mother with a Sunflower on Her Dress. And yet, something is lost in this interjection of the dress as an intermediary between the woman and the luminous blossom. La Femme au tournesol suggests an intimacy between the woman and flower, as if they exist in mutual definition, each granting equal meaning to the canvas. Though the NGA has now elected the very sensible and accurate title of Woman with a Sunflower, I would be more inclined toward Woman of the Sunflower (linguistic fidelity aside) in order to release the flower from its status as mere accessory, restoring its place as an interlocutor, shaping our reception and understanding of the figure it adorns and the painting writ large. Prepositional quibbles aside, the NGA’s reintroduction of the sunflower into the painting’s official title sets the stage for reconsidering its interpretive possibilities, namely its status in the visual and material culture of American suffrage at the time of the painting’s creation.

By way of conclusion, I want to return to Breeskin’s letter for its second instructive substitution. Without explanation—a tacit acknowledgment that one is not needed—Breeskin effortlessly substitutes “Mother” for Femme, the French word for “woman.” Womanhood and motherhood are thus elided, the former collapsed into the latter. Perhaps unwittingly, Breeskin participates in a critical erasure that has haunted Cassatt’s legacy, namely the presumption of maternity as the default mode of relation between a woman and a child. This slippage would be less troublesome had it not been widely known that Cassatt often paired unrelated women and children as models for her studio paintings.58 Breeskin was neither the first nor the last Cassatt scholar to commit this reductive error; the title of Cassatt’s first biography, for example, Achille Segard’s Mary Cassatt: A Painter of Children and Mothers (published in French in 1913), weds her to the subject of maternal relationships.59 So strong is the association between Cassatt and the maternal ideal that it has even carried over to other fields: her paintings and prints can be found littering the pages and covers of psychology textbooks and studies on child development, not to mention countless Mother’s Day cards.60 Even in the twenty-first century, critics and curators alike cannot seem to break the habit; a review of the 2018 Cassatt retrospective at the Musée Jacquemart-André declared in its title, “No one can beat Mary Cassatt at painting mothers and children.”61 The critic herself is hardly to be blamed; a section of the Jacquemart-André exhibition devoted to Cassatt’s late works bore the title “Maternités.” As Breeskin’s translation demonstrates, the theme of motherhood has become so deeply entrenched within the inherited image of Cassatt’s work that it has become an a priori interpretive category.

Feminist art historians have long recognized that the immutability of this theme has been detrimental to both Cassatt scholarship and the public imagination. Perhaps no scholar has gone further to redress this limitation than Pollock, who, in her 1998 book Mary Cassatt: Painter of Modern Women, attempted to dismantle the presumptive theme of maternity in Cassatt’s work. Pollock poses a critical challenge to art historians looking at and writing about Cassatt’s woman-and-child images:

Rather than slipping them seamlessly into the stereotype of ‘Mother and Child’ or maternité, simply because a woman painted them, we need to pose some questions. What are these paintings of? Motherhood or Childhood? Adult or Child? Family or Domestic Labor? Are they psychological portraits? Whose position are we invited to adopt before such paintings?62

For Pollock, maternity is merely one aspect of what it might mean to be a modern woman, and, importantly, it was not something that Cassatt herself ever experienced, never having had children of her own. Instead, Pollock insists, we should understand Cassatt’s women as resisting what Pollock calls the “troping of femininity.” Irreducible to the role of “mother,” these figures instead represent a rich and complex web of potential roles, characteristics, and personae.63 Under Cassatt’s brush, womanhood is not and cannot be collapsed into motherhood.

Whether because of the internalized sexism inherent in art-historical methodologies, the erasure of the sunflower from its title, or the interpretive foreclosure occasioned by the presumption of maternity, the radical symbolism of La Femme au tournesol has fallen by the scholarly wayside, hiding in plain sight for over a century. Restored to its centrality in the title, the sunflower can now be reclaimed as an active constituent in the painting’s meaning. As the principal icon of the American suffrage movement—a cause to which Cassatt was wholeheartedly devoted—the sunflower sheds its luminous light on the ways in which the painter understood the political potential of her artistic practice. Seen in this renewed context, the painting’s figural pair is released from the literalism of a mother-daughter duo. The woman, emblazoned with the symbol of suffrage, lifts the small mirror to reveal the young girl’s face, which overwhelms the mirror pane in its plenitude. The mirror is transformed into a kind of scrying glass, a glimpse into futures unknown made possible by the promise of political enfranchisement. Despite its shortcomings, the suffrage movement was at its best when it dedicated its energies to younger generations, advocating for their rights. Sunflowers—which turn instinctively towards the sun—naturally lend themselves to this progressive sensibility. As one 1888 marching song exhorted:

Put on the yellow ribbon, friends, the badge of honor true,

The sunflower turns to meet the sun, each day with hope anew,

So may we ever track the truth whose light is breaking through,

As we go marching, marching onward!

. . .

Put on the yellow ribbon, friends, and let its colors glow

Above each patriotic heart, like sunlight’s earliest flow;

‘Twill be a message to each friend, a challenge to each foe

As we go marching, marching onward!64

In painting La Femme au tournesol, Cassatt heeded the call.

Cite this article: Nicole Georgopulos, “‘The Sunflower’s Bloom of Women’s Equality’: New Contexts for Mary Cassatt’s La Femme au tournesol,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.13070.

PDF: Georgopulos, Sunflower’s Bloom

Notes

- “Mary Cassatt’s Unique Position,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 1, 1913, 9. ↵

- There are two published references to the painting that precede the Inquirer article, but they only mention it briefly in passing: Edouard Sarradin, “Notes d’art,” Journal des débats, November 26, 1908, 3; and Walter Pach, “Quelques notes sur les peintres américains,” Gazette des beaux-arts 51, no. 2 (1909): 334–35. Pach never actually addresses the painting directly, despite including a full-page reproduction. ↵

- Harriet Scott Chessman, “Mary Cassatt and the Maternal Body,” in American Iconology: New Approaches to Nineteenth-century Art and Literature, ed. David C. Miller (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 257. ↵

- Linda Nochlin, “Mary Cassatt’s Modernity,” in Women Artists: The Linda Nochlin Reader, ed. Maura Reilly (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2015), 202. Nochlin carefully avoids an anachronistic diagnosis of “Freudian displacement,” warding off an assignment of sublimated maternal desire, reminding us that, in the nineteenth century, the nudity of babies was “often envisioned as simultaneously pure and desirable” (203). ↵

- Griselda Pollock, Mary Cassatt: Painter of Modern Women (London: Thames and Hudson, 1998), 210–11. ↵

- A 1901 article in Harper’s Bazaar clarifies the codification of this kind of garment as one intended for the privacy of the home, as well as its class implications; see A. T. Ashmore, “Gowns and Negligées for House Wear,” Harper’s Bazaar 34, no. 11 (January 1901): 186–66. For examples of this style of nightgown around the time of the painting’s creation, see “Negligées & House Gowns,” Harper’s Bazar 39, no. 10 (October 1905): 910; and “House Gowns and Negligées,” Harper’s Bazar 40, no. 2 (February 1906): 150. ↵

- Stephen May, “The Triumph of Diligence: The Art of Mary Cassatt,” American Artist 63, no. 683 (June 1999): 40. ↵

- Frank Getlein, Mary Cassatt: Paintings and Prints (New York: Abbeville Press, 1980), 138. ↵

- Judith Barter, “Mary Cassatt: Themes, Sources, and the Modern Woman,” in Mary Cassatt, Modern Woman, ed. Judith Barter (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 98. Barter reproduces a detail of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes’s Ave Picardia Nutrix (1865, Musée de Picardie, Amiens) as evidence of the sunflower’s persistence as a Marian emblem, pointing out that Cassatt would surely have been familiar with the mural due its proximity to her home in Beaufresne. Indeed, the sunflower was a favorite motif of many artists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Julia Margaret Cameron, among others. On the broader history of sunflower iconography in particular, see Debra Mancoff, Sunflowers (Chicago: Thames and Hudson, 2001). On the subject of flower symbology, the so-called language of flowers—in which particular flowers were understood to signify certain feelings or meanings—was popularized in the nineteenth century but varied based on specific time and context. In popular floral emblem books, such as Charlotte Latour’s Le Langage des fleurs (Paris: Audot, 1819) or Alexis Lucot’s Emblèmes de flore et des végétaux (Paris: L. Janet, 1819), sunflowers were associated not only with the Madonna but also with pride, haughtiness, false riches, and rejuvenation; see Beverly Seaton, The Language of Flowers: A History (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995); for another key discussion of flower symbology in the nineteenth century, see Alison Syme, A Touch of Blossom: John Singer Sargent and the Queer Flora of Fin-de-Siècle Art (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010). ↵

- “Sunflower Badge for Suffrage,” Woman’s Journal, November 26, 1887, 1. The unnamed author goes on to note that the suffragists of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania—Cassatt’s home state—followed suit. ↵

- Virginia D. Young, “The Sunflower’s Bloom of Woman’s Equality,” in Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual Convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, Held in Washington, DC, January 23–28, 1896, ed. Rachel Foster Avery (Philadelphia: Alfred J. Ferris, 1896). ↵

- Margaret Finnegan, Selling Suffrage: Consumer Culture and Votes for Women (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), especially chapter 4, “From Sunflower Badges to Kewpie Dolls: Woman Suffrage Commodities and the Embrace of Consumer Capitalism.” See also Kenneth Florey, Women’s Suffrage Memorabilia: An Illustrated Historical Study (Jefferson: McFarland, 2013). ↵

- Portraits of Suffrage Leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott Among Sunflower Prints, suffrage miscellany in the Mary Earhart Dillon collection, drawings of women, some printed, 1895, n.d.; one of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, two by Nina Allender (printed), A-68, series XIII, folder 627, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. I am grateful to my anonymous reviewer for bringing this felicitous object to my attention, as well as for their attentive reading and generous suggestions for avenues of expansion. ↵

- NAWSA and its constituents represented only a particular portion of American women, namely white women of a certain social strata. Recent histories have begun to redress the insidious racialism and racism inherent in the American suffrage movement; see Lisa Tetrault, The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014); Martha S. Jones, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All (New York: Basic Books, 2020). Any discussion of Cassatt’s feminism and the suffrage movement in which she participated must be understood under these conditions. ↵

- Cassatt makes frequent mention of the Herald Tribune in her correspondence; for example, in reference to the 1915 exhibition at the Knoedler Gallery, discussed below, Cassatt wrote to Havemeyer, “My dear I am so very glad about the exhibition. It has indeed been a success and you deserve all the credit. The Herald Paris edition has an article about us.” Mary Cassatt to Louisine Havemeyer, April 29, 1915The Havemeyer Family Papers relating to Art Collecting, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (hereafter Havemeyer Family Papers), box 1, folder 13, item 08. The corresponding article, “Art Exhibitions in New York,” appeared in the Paris Herald Tribune on April 3, 1915, 3. ↵

- I am grateful to Justine de Young for drawing out the medieval aspect of the garment in Cassatt’s painting, as well as for pointing me in the direction of the digitized Harper’s Bazar archives. ↵

- On French feminism in the nineteenth century, see Claire Goldberg Moses, French Feminism in the 19th Century (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1984); Jennifer Waelti-Walters and Steven C. Hause, eds., Feminisms of the Belle Époque: A Historical and Literary Anthology (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994); James F. McMillan, France and Women, 1789–1914: Gender, Society and Politics (London: Routledge, 2000). ↵

- There are few—if any—extant records of Cassatt commenting on class or race. A rare exception is a brief comment made in a letter to Havemeyer in which Cassatt passes judgment on how upper-class people treat those in their employment, in this case, a gardener; she remarks, with a certain degree of exasperation, “I tell you my dear I am becoming absolutely socialist in my sympathies.” Mary Cassatt to Louisine Havemeyer, March 12, 1915, Havemeyer Family Papers, box 1, folder 13, item 06. ↵

- Carl Little, “Mary Cassatt: Redux,” Art New England (April/May 1999): 21. ↵

- In fact, when the US Congress passed a resolution making Mother’s Day an official holiday in May 1913, Cassatt wrote in exasperation to Havemeyer, “What do you think of that goose of a congressman getting up ‘Mother’s Day’?!,” going on to say that the congressmen’s mothers should “box their conceited ears!” Mary Cassatt to Louisine Havemeyer, May 1913Havemeyer Family Papers, box 1, folder 11, item 16, cited in Nancy Mowll Mathews, Mary Cassatt: A Life (New York: Abbeville Press, 1994), 308. ↵

- Mary Cassatt to Louisine Havemeyer, December 28, 1914, Havemeyer Family Papers, box 1, folder 12, item 13. ↵

- Louisine Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector (New York: Ursus Press, 1961), 296. Cassatt evacuated to the Breton town of Dinard, where she wrote the above-cited letter to Havemeyer. ↵

- While only eighteen works by Cassatt were listed in the exhibition catalogue, Rebecca Rabinow found an additional three works, which she published in 1993. More recently, Ruth Iskin’s examination of the Knoedler archives has yielded eight additional works by Cassatt that were featured in the show. See Loan Exhibition of Masterpieces by Old and Modern Painters (New York: M. Knoedler, 1915); Rebecca Rabinow, “The Suffrage Exhibition of 1915,” in Splendid Legacy: The Havemeyer Collection (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993); Ruth Iskin, “The Degas and Cassatt 1915 Exhibition in Support of Women’s Suffrage,” in Monographic Exhibitions and the History of Art, ed. Maia Wellington Gahtan and Donatella Pegazzano (New York: Routledge, 2020). ↵

- Louisine Havemeyer, “The Suffrage Torch: Memoirs of a Militant,” Scribner’s Magazine 72 (April 1922): 529; Rabinow, “Suffrage Exhibition,” 89–92. By financial measures, the exhibition was a success. After taking out his own profit, Knoedler cut a check to Havemeyer at the end of the exhibition for $1,375.10 (Rabinow, “Suffrage Exhibition,” 92); adjusted for inflation, that amount had a purchasing power equivalent to about $36,000 in 2021, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Inflation Calculator; see https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. ↵

- Mary Cassatt to Louisine Havemeyer, May 30, 1914, Havemeyer Family Papers, box 1, folder 12, item 05. ↵

- On the works included in the exhibition (both on and off the checklist), see Rabinow, “Suffrage Exhibition”; Iskin, “Degas and Cassatt.” ↵

- Iskin, “Degas and Cassatt,” 26. ↵

- A century later, the equal exchange between the two artists would be the subject of the 2014 exhibition Degas/Cassatt at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, curated by Kimberly A. Jones; see Kimberly A. Jones et al., Degas/Cassatt, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel, 2014). ↵

- Mary Cassatt to Louisine Havemeyer, March 12, 1915, Havemeyer Family Papers, box 1, folder 13, item 06. ↵

- Louisine Havemeyer, Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer’s Remarks on Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt, April 6th 1915 (New York: Kneodler, 1915), n.p. ↵

- This is not to say, however, that Cassatt’s works in the show might not have been perceived as having such undertones. Writing about an entirely different exhibition that benefited the suffrage cause—also staged in New York in 1915—Mariea Caudill Dennison has made a forceful case for how the proliferation of images of women and children in such exhibitions would have been understood as closely related to suffrage messaging. See Mariea Caudill Dennison, “Babies for Suffrage: The Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture by Women Artists for the Benefit of the Woman Suffrage Campaign,” Woman’s Art Journal 24, no. 2 (Autumn 2003–Winter 2004): 24–30. ↵

- The second extant tondo, known only today through a black-and-white photograph, depicts another young woman in a flowing negligée with a nude child. See Adelyn Dohme Breeskin, Mary Cassatt: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Oils, Pastels, Watercolors, and Drawings (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute, 1970), cat. no. 471. Though the third mural was never completed, a study for a child figure in the collection of the Speed Art Museum (1964.22) in Louisville, Kentucky, suggests a continuity with the other two. ↵

- Ruthann Hubbert-Kemper and Jason L. Wilson, eds., Literature in Stone: The Hundred Year History of Pennsylvania’s State Capitol (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee, 2006), 234. ↵

- “MISS CASSATT’S PAINTINGS: Striking Collection by American Girl Shown in Paris,” Washington Post, March 6, 1910, A14. ↵

- Board of Lady Managers, “Preliminary Prospectus,” 1891; reproduced in Sally Webster, Eve’s Daughter/Modern Woman: A Mural by Mary Cassatt (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 57. ↵

- Webster, Eve’s Daughter/Modern Woman, 10. ↵

- The most popular instance of this retooling was the publication of The Woman’s Bible, a collection of commentary edited by Elizabeth Cady Stanton on both the New and Old Testaments, scrutinizing the foundations of Judeo-Christianity for its misogyny and patriarchal ideas, maintaining that religion was, in its essence, a source of subjugation of women. Received as highly radical and subversive, much of the text is dedicated to freeing figures such as Eve and Mary from their biblical reputations and roles, instead positioning them among a laudatory pantheon of historical and contemporary women. Moreover, a strong Catholic contingent contributed to the flourishing of French feminism at the turn of the century, coming at the tail end of the Marian revival of the nineteenth century. On Catholic feminism in France, see Steven Hause and Anne Kenny, “The Development of the Catholic Women’s Suffrage Movement in France, 1886–1922,” Catholic Historical Review 67 (1981): 11–30. ↵

- Cassatt’s engagement with the motif of the Madonna can be readily traced through her admiration for and knowledge of Old Master painting, with which she became deeply familiar through her travels in Italy and Spain in the early 1870s. In 1871, she was commissioned by the second bishop of Pittsburgh to carry out copies of two paintings by Correggio in Parma; though the resultant paintings are no longer extant, at least one of them focused on the Madonna, namely Correggio’s Coronation of the Virgin (1522, Galleria Nazionale, Parma, previously in the apse of the church of San Giovanni Evangelista). On Cassatt’s travels and her study of Spanish and Italian masters, see M. Elizabeth Boone, “Mary Cassatt, Modern Woman, and the Ritual of Spanish Travel,” in Vistas de España: American Views of Art and Life in Spain, 1860–1914 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 89–113. ↵

- Roger Marx, “Awakening of the Baby,” in Noteworthy Paintings in American Private Collections, ed. John La Farge and August F. Jaccaci (New York: August F. Jaccaci, 1907), 355. Marx began drafting this essay as early as 1904. ↵

- Mary Cassatt to Louisine Havemeyer, December 24, 1902; reproduced in Cassatt and Her Circle: Selected Letters, ed. Nancy Mowll Mathews (New York: Abbeville Press, 1984), 277. ↵

- Here I retain the francophone term rather than the English translation of “social art” due to the latter’s proximity to later mid-twentieth-century connotations. On Marx, see Catherine Meneux, “Roger Marx (1859–1913), critique d’art” (PhD diss., Université de Paris IV-Sorbonne, 2007). ↵

- Roger Marx, “De l’Art social et de la nécessité d’en assurer le progrès par une exposition,” in L’Art Social (Paris: Bibliothèque Charpentier, 1913), 50. Translation mine. ↵

- “On ne saurait restreindre à une classe le privilège de ses inventions; il appartient à tous, sans distinction de rang ni de fortune; c’est l’art du foyer et de la cité-jardin, l’art du château et de l’école, l’art du bijou précieux et de la broderie paysanne; c’est aussi l’art du sol, de la race et de la nation.” Marx, “De l’Art social,” 50–51. ↵

- For example, Marx exhorts, “Too many women have made the mistake of ignoring, in the practice of their art, the special obligations laid upon them by organic laws. Except in the case of abnormal natures, certain tasks demand masculine energies.” Cassatt, he explains, avoids this very misstep. Marx, “Awakening of the Baby,” 354. ↵

- Mary Cassatt to Roger Marx, c. 1910, “Cassatt, Mary,” collection Roger Marx, Bibliothèque Jacques Doucet, Institut national d’histoire de l’art, Paris, autographes 112, 59. I am grateful to James H. Rubin for his assistance in untangling Cassatt’s at times unintelligible handwriting, exacerbated by her grammatically imperfect and imprecise French. I am further indebted to Catherine Dossin for assisting me in identifying one of the exhibitions to which this letter refers—Die Kunst der Frau, held at the Vienna Secession in 1910—which led me to confirm the date of the letter. As it happens, there is a striking visual resonance between La Femme au tournesol and a painting by Vigée Le Brun (recently acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019.141.23) of her daughter looking into a mirror, her reflection’s gaze similarly meeting the viewer’s. It is possible that Cassatt saw the painting when it hung in an exhibition at the Louvre in 1885. ↵

- See invoices from S. Mayer (dated November 1906) and Durand-Ruel & fils (dated May 1905) in Fonds Roger Marx, Bibliothèque Jacques Doucet, Institut national d’histoire de l’art, Paris (hereafter Fonds Roger Marx), carton XXI, série 5, dossier 3. I am deeply grateful to Jakub Koguciuk for providing invaluable research assistance at the INHA archives in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. ↵

- Mary Cassatt to Roger Marx, July 24, 1906, “Cassatt, Mary,” collection Roger Marx, Bibliothèque Jacques Doucet, Institut national d’histoire de l’art, Paris, autographes 112, 59. ↵

- “6. Le Miroir, appartient à M. R.M.” Tableaux et Pastels par Mary Cassatt: Exposition du 3 au 28 novembre 1908 (Paris: Durand-Ruel, 1908), n.p. ↵

- A simple search in the newly digitized and updated Cassatt catalogue raisonné for the title “Mother and Child” yields no fewer than 150 results. I am grateful to Elizabeth Oustinoff of the Adelson Galleries for granting me early access to this (as yet unpublished) invaluable resource, soon to be accessible at marycassatt.com. ↵

- The change of title from Mother and Child to Woman with a Sunflower was made official by a memo dated February 22, 2019 (Department of Curatorial Records, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, file 1963.10.98), and it was occasioned by the curators responsible for the painting learning of the research I present in the current article. I am profoundly grateful to Mary Morton and Kimberly A. Jones of the Department of French Paintings for their openness and collaboration on this matter, among many others. ↵

- Catalogue des tableaux, pastels, dessins, aquarelles, sculptures faisant partie de la collection Roger Marx, 11–12 mai 1914 (Paris: Galerie Manzi-Joyant, 1914), cat. no. 15. ↵

- In addition to the official sales catalogue, two handwritten inventories of Marx’s collection are preserved in his archives. One, undated, is organized by the rooms in which works were hung; under the heading “Grande Galerie,” four works by Cassatt appear, including Femme jaune et enfant. The second inventory, dated 1911, is alphabetical; one listing reads, “Cassatt mère {au tournesol} et enfant,” with the bracketed phrase written below the word “mère,” as if to insert it. Despite the disparities between these entries (and with the final official title in the sales catalogue), it is clear that Marx’s titles consistently gestured to the sunflower and its distinctive color; Fonds Roger Marx, carton XXI, série 5, dossier 2. ↵

- Important Paintings from the Havemeyer Estate, part 1 (New York: American Art Association, Anderson Galleries, 1930), 59 (cat. no. 82). As discussed above, Havemeyer would go on to include the painting in her 1915 exhibition for suffrage at the Knoedler Gallery. Intriguingly, this is the only time that the painting would be exhibited or published in Cassatt’s lifetime with a title that referred to maternity, namely Mother with Baby Reflected in Mirror (cat. no. 50). However, there is good reason to believe that Havemeyer was not responsible for producing the small exhibition catalogue in which this title appears. For one thing, the checklist is highly incomplete, representing only a fraction of the works that appear in the installation photographs (as discussed by Rabinow and Iskin, as cited above in n. 23). Moreover, the life dates given to Cassatt in the catalogue are incorrect; her birth year is listed as 1855 rather than 1844 (Loan Exhibition of Masterpieces by Old and Modern Painters, 21). Given their closeness at the time, I find it hard to believe that Havemeyer would have made such a radical error of over a decade (and, though this might be coincidence, 1855 is Havemeyer’s birth year). As such, I am not convinced that the title here necessarily reflects Havemeyer’s (and, by extension, Cassatt’s) preferences. ↵

- “Collection Inventory #1, C, circa 1964,” Chester Dale Papers, c. 1883–2003, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC, series 4, box 2, folder 23. ↵

- Department of Curatorial Records, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, file 1963.10.98. The second document has a typewritten notation “David E. Rust” at the lower left, suggesting that the autograph notations were the work of Rust, then curator of French, British, and Spanish painting at the NGA. ↵

- The one exception was the painting’s inclusion in the 1998–99 retrospective, for which it was restored to its first public title, Le Miroir. See Barter, Mary Cassatt, 327 (cat. no. 89). ↵

- Adelyn Dohme Breeskin to John Bullard, July 15, 1968, Department of Curatorial Records, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, file 1963.10.98. ↵

- See Chessman, “Mary Cassatt,” 243; Nancy Mowll Mathews, Mary Cassatt (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987), 72–76. ↵

- Achille Segard, Mary Cassatt: Un Peintre des enfants et des mères (Paris: Ollendorff, 1913). The ascription of maternity to Cassatt’s works is often traced back to comments by J. K. Huysmans in his review of the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition. See Huysmans, “L’Exposition des Indépendants en 1881,” in L’Art moderne (Paris: Plon-Nourrit, 1883), 256–57. On the gendered criticism of Cassatt in her lifetime, see Pamela Ivinski, “‘So Firm and Powerful a Hand’: Mary Cassatt’s Techniques and Questions of Gender,” in Women Impressionists, ed. Ingrid Pfeiffer and Max Hollein (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2008), 178–205; Ingrid Pfeiffer, “Impressionism Is Feminine: On the Reception of Morisot, Cassatt, Gonzalès and Bracquemond,” in Pfeiffer and Hollein, Women Impressionists, 12–30. ↵

- See, for example, the cover of Susan P. Gelman and James P. Byrnes, eds., Perspectives on Language and Thought: Interrelations in Development (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991). ↵

- Laura Freeman, “No One Can Beat Mary Cassatt at Painting Mothers and Children,” Spectator, May 5, 2018, https://www.spectator.co.uk/2018/05/no-one-can-beat-mary-cassatt-at-painting-mothers-and-children. ↵

- Pollock, Mary Cassatt, 187. ↵

- Pollock, Mary Cassatt, 122. ↵

- “The Yellow Ribbon: Written for the Woman’s Jubilee Air—Marching through Georgia,” Woman’s Tribune, March 28, 1888, 1. ↵

About the Author(s): Nicole Georgopulos is Assistant Professor in the Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory, at the University of British Columbia.