Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History

Project Manager and Digital Art History Editor, Panorama

Contributors

Theresa Avila, “Plotting Counter Tactics to Erasive Strategies of Manifest Destiny within US Landscapes and National Parks”

Carolin Görgen, “Californian Women Photographers in the US Archival Landscape: Toward a More Inclusive History of American Photography”

Mary Okin with Celie Mitchard, “Mining @ Tenth Street: Visualizing New York City’s Tenth Street Studio Building”

Helena Shaskevich and Lia Robinson, “Analog Video in the Age of Digital Data: A Case Study of Shigeko Kubota’s ‘Social Practice’”

Introduction

Johnathan W. Hardy and Diana Seave Greenwald

The use of digital technologies in the humanistic disciplines—including art history—has largely lagged behind the rest of academia. This slow uptake of digital and quantitative approaches has limited the range of methods available to art historians, cutting off many potentially productive avenues of research. “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History,” a joint project funded through a generous grant by the Terra Foundation for American Art and administered by Panorama: The Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art, seeks to fill this theoretical and methodological lacuna. The grant makes it possible for the Panorama team to guide a pioneering generation of art historians through workshops, one-on-one meetings, and technical guidance. Our mission for this project, in addition to producing high-quality, peer-reviewed articles for Panorama, is to contribute to a scholarly environment in which digital art history is seen as a powerful tool for analysis and research that address both long-standing and emerging scholarly questions.

In early 2020, Panorama circulated an international call for proposals, receiving proposals on a wide array of topics. With a blind review from the Panorama Advisory Council and guidance from the Executive Editors, Diana Seave Greenwald (Digital Art History Editor), and Johnathan W. Hardy (Project Manager, “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History”), six scholars were chosen to participate in this pioneering project. The workshop’s goal was to foster an environment of collegiality, collaboration, and innovation, in addition to providing access to digital art history resources and expertise that would otherwise be unavailable at most participants’ home institutions.

The core of the workshop was held virtually from February 27 to March 1, 2021. Invited participants, the Executive Editors, the Digital Art History Editor, the Project Manager, and the Managing Editor gathered on Zoom. The workshop began with each participant introducing their project to the group and receiving feedback from their fellow participants and the editors on the scope, methodological approaches, and possibilities for future publication, either with Panorama, with another journal, or in the form of a lasting website or other public-facing web presence. Following the workshop session, the cohort was introduced to a range of methodological approaches—from basic statistical analyses, to data visualizations, to the use of GIS mapping systems—that participants might use to further their own projects and address the research questions at the core of their inquiries.

The culmination of the multiday workshop was a public keynote lecture by Paul Jaskot (Duke University), “Thinking about Visibility and Invisibility in the Art Historical Canon: The Tensions between Evidence and Data in Digital Art History.” More than 550 people from every (inhabited) continent registered for the event. This keynote highlighted real-world applications of digital humanities, allowing the general public and workshop participants to see the possibilities that a digital approach to art history can offer.

Below, we highlight a cohort of developing digital art historians. The first project selected for publication as a full-length peer-reviewed feature was “Commemoration of an Epoch: Mapping Monuments to the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the United States” by Sierra Rooney, which is available here. However, in order to highlight the exciting work that all of our workshop participants are doing—in addition to Rooney—we wanted to provide a platform for them to share the projects they brought to and developed through the Terra-sponsored workshop.

The studies detailed below, ranging from a deep dive into the gendered construction of early photography in California, to an intensive study of the residents of the Tenth Street Studio Building, to an examination of the erasure of Indigenous culture in national parks, and, not least, to the unexplored (and unacknowledged) work of Shigeko Kubota, all showcase the budding field of digital art history. As the reader will come to see through the following studies, the authors showcase the diverse applicability of digital techniques to age-old questions in the art-historical canon. We look forward to seeing how these studies grow and how they will help shape a new generation of art-historical research.

Cite this introduction: Johnathan Hardy and Diana Seave Greenwald, introduction to “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History,” special section, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12824.

PDF: Hardy and Greenwald, Toward a More Inclusive DAH

————————————————–

Plotting Counter Tactics to Erasive Strategies of Manifest Destiny within US Landscapes and National Parks

Theresa Avila, Curator and Assistant Professor of Non-Western Art History, California State University Channel Islands

For Plotting Counter Tactics, I propose to build a database that relates attributes of illustrations of US national parks—starting with a focus on Yosemite National Park—to government policies that affected the Indigenous populations living both in and around those same parks, and that tracks Indigenous communities’ own engagement with these spaces. By tracking intersecting visual and political histories, I hope to provide quantitatively grounded answers to questions like: How are Indigenous communities represented by or within the narrative and visualization of Yosemite National Park? What is the story that images of US national parks tell? And how does it compare to the history and belief systems of Indigenous communities? Answering these questions also has implications for understanding how imperial practices and nation-building defined who an American citizen could be and who could be an inhabitant or custodian of the land in the United States.

Through a series of meetings that took place between the summer of 2020 and the summer of 2021 with Panorama editor Diana Seave Greenwald and project manager Johnathan Hardy, I began to re-envision my project and transform my approach in terms of the type of data I collect and the methods of visualization I seek to engage. From Greenwald, I gained models for applications of data to examine traditionally marginalized peoples and to grapple with questions about the dominance of particular canonical subjects in art history. Hardy supported my development and investigation of data organization and interpretation as well as the use of various software suites that are designed for geospatial, statistical, and network analysis.

My focus has turned to Yosemite National Park, as the first site to be nationally protected for public use in the United States. Reading the history of massacre and dispossession of Indigenous communities as part of the development of California’s national parks prior to my first trip to Yosemite in June made the visit surreal. Many of the popular spots to pose for photos are sites of violence, forced removal, and destruction of Indigenous villages. Teasing out and visualizing the simultaneous history of Indigenous and Anglo communities at Yosemite within a digital space is now a primary objective for this project.

During the summer of 2021, I led undergraduate students Erica Guenthner, Yvette Hernandez, and Aricka Wedlaw to collect data for the project as part of the CSU Channel Islands Student Undergraduate Research Fellowship. Among the types of data collected, we conducted word scrapes of significant texts to produce word maps focused on language about Indigenous communities and national parks to highlight the nature of thought related to both (figs. 1, 2). As my team began our data collection, stories began to emerge in newscasts and on social media about the uncovering of hundreds of bodies of Native American children who had been students at Anglo faith-based boarding schools where they were forced to live. The horror and sadness of this news made real the extent and magnitude of anti-Indigenous bigotry in the United States and ignited a fire in our data-collection efforts. I continue to build my collection of data on Yosemite National Park, working toward engaging StoryMaps and/or Omeka to visualize what has been collected thus far. This project is an effort to revise OUR histories to be inclusive of the meaningful lives Manifest Destiny and Anglo settler colonialism have otherwise buried and erased.

Cite this project summary: Theresa Avila, “Plotting Counter Tactics to Erasive Strategies of Manifest Destiny within US Landscapes and National Parks,” in “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History,” special section, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12824.

PDF: Avila, Plotting Counter Tactics

————————————————–

Californian Women Photographers in the US Archival Landscape: Toward a More Inclusive History of American Photography

Carolin Görgen, Associate Professor of American Studies, Université Paris-Sorbonne

My digital art history project traces the contributions and archival legacies of Californian female photographers around 1900. In this period, photography became an increasingly accessible practice; simultaneously, California emerged as the eminent cultural symbol of the American West. Although the region was home to the largest photo community in the country—the four-hundred-member-strong California Camera Club (CCC)—scholarship has tended to frame this history as a succession of male “master” photographers. This canonic narrative has marginalized the disproportionately large number of women photographers (twice the national average!)1 active in the camera club, as well as their archival legacies.

Based on a dataset I created of the CCC’s fifty most productive members, my project aims to visualize the exhibition work of female club members during their lifetimes as well as their current preservation in US photo archives. The data is drawn from exhibition catalogues, the club’s periodical Camera Craft, as well as regional archives consulted over the course of four years. The selection of members in the dataset reflects the gender ratio of the CCC around 1900, when women represented some 20 percent of the total. Since the CCC practiced exclusionary policies toward the state’s minority populations—notably Black, Asian American, and Indigenous—the data can only integrate the contributions of the Bay Area’s European American circle. Unfortunately, it does not take into consideration works produced by people of color outside of this network (for whom very few records survive).

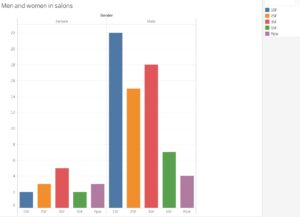

In the 1900s, as the club sought recognition amid the fine arts, members launched a series of salons (fig. 1). The first three in this series, hosted between 1901 and 1903, represented an unprecedented exhibition opportunity for western women photographers. Over the course of two years, their numbers steadily rose, from 10 percent in 1901 to almost 33 percent by 1903. This count reflects the tenor of both periodicals and correspondence of the time. We can observe an overall decline in salon participation by the mid-1910s, due to the dispersal of first-generation membership—that is, photographers who had been active since the 1890s and gradually abandoned the group. Nevertheless, the proportion of female contributors grew steadily. Notably, by the time of the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, for every four male photographers exhibiting, there were three female club members.

Going forward, I want to expand my dataset and data visualizations both chronologically and geographically with data from the next generation of California women photographers. By the 1920s, a set of prolific practitioners, such as Imogen Cunningham and Laura Gilpin, showed their work up and down the West Coast with a variety of photography clubs. Data from this later moment in time will allow me to trace whether the upward trajectory in the share of women photographers participating in exhibitions persisted. I also want to extend my dataset to gather information about the number of female photographers taking on positions as salon organizers or photo-journal editors.

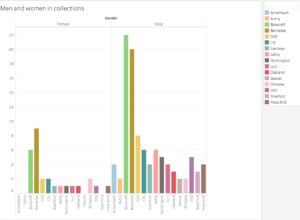

As this research is rooted in regional archives, the project also explores the archival repercussions of female production. To what extent is the constant growth of female photo work around 1900 represented in collecting institutions? Figure 2 provides a glimpse into this ongoing research, which currently confirms two of my hypotheses. First, the overall archival presence of male club members is much larger than that of female photographers, whose work oftentimes is recorded only in the contemporaneous literature and not extensively preserved in photography archives nor discussed in later literature. Second, while the overall archival presence of western women is low, there are exceptions to this pattern in the two archival collections that hold the greatest variety of club materials—the Bancroft Library at Berkeley and the Beinecke Library at Yale. While, on the whole, CCC materials are scarce, and women tend to be underrepresented, the two institutions that hold larger troves confirm the club’s gender ratio and reflect the broader impact of women: at the Beinecke Library, almost half of the collected materials come from women (especially thanks to the Peter Palmquist Collection), and at the Bancroft Library they amount to almost 25 percent of the CCC’s overall presence. In the future, my inventory would benefit from data in archival collections beyond the two coasts, notably the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, which is home to significant collections of later women photographers, notably Laura Gilpin.

As part of an ongoing project, the data visualizations presented here have helped me envision my corpus on a new scale. Assembling the mass of material in a spreadsheet and analyzing it with Tableau software has brought to light some of the striking lacunas of photo-historical research, notably regarding the archival absence of female camera club members. At the same time, visualizing the proportional contributions of women and men has allowed me to trace membership trends over an extended period and to understand the CCC’s social dynamics. I am eager to continue to use these methods to analyze these trends over a broader time scale and in other areas of photographic activity, like editorial work.

Notes

Cite this project summary: Carolin Görgen, “Californian Women Photographers in the US Archival Landscape: Toward a More Inclusive History of American Photography,” in “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History,” special section, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12824.

PDF: Görgen, California Women Photographers

————————————————–

Mining @ Tenth Street: Visualizing New York City’s Tenth Street Studio Building

Mary Okin, PhD candidate, University of California, Santa Barbara, with Celie Mitchard, Research Assistant, University of California, Santa Barbara

Mining @ Tenth Street: Visualizing New York City’s Tenth Street Studio Building is a macro-analysis of the canonical creative cluster and architectural structure that existed at 51 West Tenth Street (fig. 1) in Greenwich Village from 1858 to 1956. This project began in 2018 as an experiment with mining Annette Blaugrund’s pioneering work on the building’s nineteenth-century history, particularly her publication of rosters that catalogued tenant data: names, life spans, and years of occupancy.1 Her rosters and qualitative analysis demonstrate the centrality of the Hudson River School and American Impressionist painters within this space and model how to include understudied figures in the history of American art. Working initially on validating her data using recently digitized materials, Mining @ Tenth Street has since recovered more than two hundred additional nineteenth- and twentieth-century tenants and collected granular data about them, including age, gender, ethnicity, birthplace, education, travel, military service, preferred genre, and other quantifiable information.

This project demonstrates how big data and digital humanities tools enable us to trace the building’s gradual slippage from Gilded Age art center to postwar anachronistic periphery. Speaking to current debates about canon formation, the project positions the Tenth Street Studio Building as a particularly rich case study for exploring how to create a more inclusive American art history. Mining a more expansive dataset in search of aggregate insights about the building, we discover the ways in which it elucidates patterns of exclusion in art history and museum collections. In pushing against traditional art history methodology, namely monographic writing and chronological ordering, we illuminate the messy and fascinating life of the Tenth Street Studio Building and its substantial contributions to American cultural history within and beyond the visual arts.

Currently, for Mining @ Tenth Street we are processing data computationally to create visualizations, including a timeline, social network reconstruction, and mapping of the building’s transnational geographic reach, and to assemble data necessary for creating a 3D model that can be used to explore the building’s influential design and identify the spatial proximity of specific tenants to one another in the building. These and other avenues of growth for the project have benefited greatly from participation in Panorama’s “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History” initiative. Feedback from Diana Greenwald and Johnathan Hardy, as well as other members of the journal’s editorial board, has been invaluable to the project’s data-gathering methods, research agenda, findings, and future goals, which include our forthcoming Panorama article next fall and our concurrent development of a website that will be an open-access scholarly resource.

As the project team’s leader, I also found inspiration and encouragement in Paul Jaskot’s keynote address, “Thinking about Visibility and Invisibility in the Art Historical Canon: The Tensions between Evidence and Data in Digital Art History,” and the Q&A that followed at Panorama’s workshop. If our aim is to interrogate power relations in order to create a more inclusive digital art history, Jaskot suggested, then coauthorship is a way to render visible the networked efforts of collaborators. This advice is very much aligned with feminist approaches to digital humanities, particularly the principle of making labor visible.2 The publications I envision creating with the data—and data visualizations we are assembling—will take their cue from Jaskot, from proponents of feminist approaches to working with data, and from the Studio Building’s history of collaborative labor by crediting all those involved in constructing Mining @ Tenth Street.3

—M.O.

Notes

Cite this project summary: Mary Okin with Celie Mitchard, “Mining @ Tenth Street: Visualizing New York City’s Tenth Street Studio Building,” in “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History,” special section, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12824.

PDF: Okin and Mitchard, Mining @ Tenth Street

————————————————–

“Analog Video in the Age of Digital Data: A Case Study of Shigeko Kubota’s ‘Social Practice’”

Helena Shaskevich, PhD candidate in Art History at the Graduate Center, City University of New York

Lia Robinson, Director of Programs and Research, Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation

If Nam June Paik truly is the “father of video art,” as so many scholars claim, then Shigeko Kubota is in many ways its mother, performing the unacknowledged and undervalued labor of managing the “house” of video and taking care of its inhabitants.1 My digital art history project for Panorama, which performs a data-driven deep dive into Kubota’s networks, argues that Kubota’s legacy must be understood as a lived, “social practice” of care for video art and its communities (fig. 1). An émigré from Japan, Kubota (1937–2015) dedicated most of her career to conceptualizing video as a connective tissue; she imagined video as an electronic medium that could bridge geographic divides to build new artistic communities while processing personal and collective experiences.2 This philosophy is manifest in her frequent artistic collaborations, including those with Fluxus artists and her short-lived multicultural collective Red, White, Yellow, and Black, as well as her own writings and video work, which often provocatively liken video’s electronic signals to the fluid properties of water.3 “The role of water in nature is comparable to the function of video in our life,” Kubota writes. “In preindustrial times, rivers connected communities separated by long distances, spreading information faster than any other means. Today the electronic signals speed our messages and connect us globally.”4 Finally, when she was appointed the inaugural video art curator at Anthology Film Archives (AFA) in 1974, it was not only an important moment in the histories of video art, reifying video art’s status as artistic medium at such an early stage in its development, but also a meaningful and prescient acknowledgment of her role as a steward of the video art community.

The original data for this project came from a series of interviews with video artists conducted for the digital archive of the Women’s Video Festivals (WVF).5 To mine the interviews for patterns, I transformed them into a word cloud, a simple data visualization which correlates the frequency of a term with size and highlights important text by making it larger. The frequency with which Kubota’s name appears in the interviews was one of the surprising results of this exercise and encouraged me to dig deeper. In collaboration with Lia Robinson of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation, I began mapping Kubota’s relationships to artists, collectives, and institutional spaces during the 1970s. The map, which is an ongoing project, has already highlighted several interesting connections. For instance, the node related to the Women’s Video Festivals (fig. 2) displays a burgeoning and intimately interconnected network of small artist spaces devoted to women’s video and film. Kubota not only exhibited her own tapes during the festivals, but also, in coordination with the festivals’ curator, Susan Milano, screened many of the tapes during her tenure at AFA and attempted to organize an international iteration of the festival in Japan. As the network map helps further unearth these connections, it will inevitably reveal the transformative role Kubota played in shepherding countless video artists, especially women of color.

—H.S.

Notes

1 Nam June Paik is referred to as the “father” or “founder” of video art too widely in the literature to recite. For an important scholarly discussion of Paik and his writings, see, for example, John G. Hanhardt, Gregory Zinman, and Edith Decker-Phillips, eds., We Are in Open Circuits: Writings by Nam June Paik (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019).

2 Mayumi Hamada et al., “A Message from Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation,” in Viva Video: The Art and Life of Shigeko Kubota (Tokyo: Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2021), 4.

3 For additional discussions of Kubota’s collaborations, see Melinda Barlow, “Red, White, Yellow, and Black: Women, Multiculturalism, and Video History,” Quarterly Review of Film and Video 17, no. 4 (2000): 297–316; Emily Watlington, “Red, White, Yellow, Black: A Multiracial Feminist Video Collective, 1972–73,” Another Gaze, December 23, 2019, https://www.anothergaze.com/red-white-yellow-black-multiracial-feminist-video-collective-1972-73; Midori Yoshimoto, “Fluxus Nexus: Fluxus in New York and Japan,” MoMA Post: Notes on Art in a Global Context, July 9, 2013, https://post.moma.org/fluxus-nexus-fluxus-in-new-york-and-japan.

4 “Shigeko Kubota, 1976–79,” in Shigeko Kubota: Video Sculpture, ed. Mary Jane Jacob (New York: American Museum of the Moving Image, 1991), 43.

5 Founded by Steina Vasulka and organized by artist Susan Milano, the Women’s Video Festivals (WVF) represent a significant, but largely forgotten, moment in feminist media. Originally hosted by the Kitchen during the early 1970s, the festivals were eventually moved to the now-defunct Women’s Interart Center, a significant hub for feminist art and politics during the 1970s and 1980s in New York City. Featuring tapes, sculptures, and viewing environments created, produced, or directed by women, the WVF included work by influential video artists like Joan Jonas, Shigeko Kubota, and Susan Mogul, alongside more didactic and activist-oriented tapes by grassroots collectives and guerrilla television community groups.

Cite this project summary: Helena Shaskevich and Lia Robinson, “Analog Video in the Age of Digital Data: A Case Study of Shigeko Kubota’s ‘Social Practice,’” in “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History,” special section, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12824.

PDF: Shaskevich and Robinson, Analog Video in the Age of Digital Data

————————————————–

Cite this special section: Johnathan Hardy and Diana Seave Greenwald, ed., “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History,” special section, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12824.

PDF: Hardy and Greewald, Toward a More Inclusive DAH

About the Author(s): Johnathan W. Hardy is a doctoral candidate in art history at the University of Minnesota and Project Manager of “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History.” Diana Seave Greenwald is Assistant Curator of the Collection at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and Digital Art History Editor for Panorama.