“A Kind of Traveling Gazette”: Edward Lamson Henry’s The Latest Village Scandal, Gossip, and History at the Dawn of Sensational Journalism

In 1885, as the first serious debates over the social role of the press raged in the wake of a drumbeat of revelations about the misdeeds of prominent politicians, religious leaders, and society figures, Edward Lamson Henry (1841–1919) painted The Latest Village Scandal (fig. 1). A grizzled farmer gossips to passersby, as their buckboards clatter past each other on a cratered country road. Eager to share some piquant piece of news, the tattler leans inward toward his neighbors. His profile abuts the backside of his horse, caricaturing him as a “horse’s ass” or comic fool. While the mother scrunches her face into a disapproving scowl, her husband grins buffoonishly. Tickled by the amusing tale, their sable steed also perks its ears attentively, cocks its muzzle toward the gossip, and whinnies with laughter. Royal Cortissoz delighted in these genial touches and in the feeling of sociability that permeates the scene. “Somehow one can’t help feeling that there is a kind of innocence about the ‘scandal,’” he wrote. “That is the ultimate impression that Henry leaves, one of the sweet sentiment, the neighborliness, the friendly domesticity to which he was essentially dedicated.”1

Henry is celebrated as a meticulous painter of old-fashioned genre scenes unsullied by the ravages of modern life. Indeed, The Latest Village Scandal’s picturesque world of neighborly prattle, horse-drawn carriages, and stretches of scrubby farmland seems far away from the vexing forces of social fragmentation, industrialization, and urbanization that roiled American life in the decades following the Civil War. Yet Henry’s seemingly antiquated scene wryly investigates his generation’s troubled relationship to mass-mediated scandal. The nostalgic painting of provincial oral gossip is haunted by allusions to the rapid mass production and nationalization of newspaper scandal in the 1870s and 1880s. The work both blithely evokes simpler times and anxiously meditates on the expanding market for printed gossip and scandal in Henry’s own era. It even animates the rhetoric of influential press critics, among them the first writers to advance the principle of “the right to privacy,” which remains a legal and conceptual cornerstone of modern experience. At the same time, however, the painting also gleefully participates in the emerging economy of scandal by contriving specific sensations that dominated the news as Henry worked. This ambivalence between the clashing perspectives of the painting toward publicity, one distressed and one more sanguine, was symptomatic of Henry’s own predicament: he was an enthusiastic reader of newspaper scandal whose patrons felt vulnerable to media exposure and renounced the sensational press with special zeal. Henry depended on their largesse and equivocally tailored his work to their tastes.

Street Gossip, Printed Gossip

Henry and his wife Frances Livingston Wells built a summer retreat in the upstate hamlet of Cragsmoor, New York, in 1884. In this remote village nestled in the Shawangunk Mountains, they sought escape from the dizzying pace of life in New York City, where Henry maintained a winter studio, as well as a deeper connection to the vanishing scenery and traditional ways of life still practiced by the longtime inhabitants of the region. Henry painted a version of The Latest Village Scandal, now lost, in the first season of his rustic idyll, and the surviving second canvas one year later.2 The composition unfolds like a trip down memory lane, its rutted, one-lane roadway sweeping the viewer’s gaze from the foreground up a steep slope to a vista overlooking miles of farmland and pristine forests. The mounting hills and high horizon of the countryside form a visual barrier between foreground and background that implies the geographical and spiritual isolation of the village from the modern world beyond. Henry’s fidelity to historic details such as the primitive buckboards, probably modeled on examples in his own collection of early American wagons, lend an aura of authenticity to his evocation of old-fashioned village life.

The central pageant of neighborly gossip also recalls bygone times. In 1889, Henry Adams recollected how the first writers on the Republic “spoke with annoyance of the inquisitorial habits of New England and the impertinence of American curiosity.”3 More recently, historian David Flaherty has confirmed that “gossip was inevitably prevalent” in early America, where the absence of formal news media, the general dependence on oral communications, and the isolated nature of rural life all fostered the pastime.4 The vast, unpeopled landscape of The Latest Village Scandal evokes the rural isolation that heightened the attraction of gossip. A French visitor to the United States in 1802 called curiosity “so natural to people who live isolated in the woods, and seldom see a stranger,” such as Henry’s characters.5 Likewise, in The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820), Washington Irving described how sequestered villagers hungry for news “greeted with satisfaction” the itinerant schoolmaster Ichabod Crane, whom Irving characterized as “a kind of traveling gazette, carrying the whole budget of local gossip from house to house.”6

Irving’s description of Crane as a circulating newspaper recalls the work of numerous scholars and critics who have framed small-town village gossip as the historical antecedent to modern industrial newspaper gossip. For example, Janna Malamud Smith has written that the task of modern newspaper stories “was partly to replace the informal gossip of village life; it was impossible to whisper fast enough to pass important gossip to a whole city and few were inclined to whisper to strangers.”7 She suggests that the slow pace and interpersonal nature of oral gossip hampered its spread as opposed to the rapid and broad distribution of the printed newspaper feature. Similarly, Edward Bloustein argued that oral gossip was less powerful and pernicious in the tight-knit communities of early America than printed gossip in later times. He wrote:

(T)he small town gossip did not begin to touch human pride and dignity in the way metropolitan newspaper gossip mongering does. . . . The whispered word over a back fence had a kind of human touch and softness while newsprint is cold and impersonal. Gossip arose and circulated among neighbors, some of whom would know and love or sympathize with the person talked about. Moreover, there was a degree of mutual interdependence among neighbors which generated tolerance and tended to mitigate the harshness of the whispered disclosure.

Because of this context of transmission, small town gossip about private lives was often liable to be discounted, softened and put aside. A newspaper report, however, is spread abroad as part of a commercial enterprise among masses of people unknown to the subject of the report and on this account it assumes an imperious and unyielding influence. Finally . . . the gossip was never quite believed or was grudgingly and surreptitiously believed, while the newspaper tends to be treated as the very fount of truth and authenticity, and tends to command open and unquestioning recognition of what it reports.8

Bloustein described a small-town America where neighborly goodwill tended to squelch the potentially damaging effects of gossip. Legal assistance was rarely necessary, although in extreme circumstances the victims of gossip could seek redress under the laws of defamation and barratry.

Henry’s generation, however, was the first to look back on village gossip nostalgically. The late nineteenth century created the perception of small-town oral gossip as innocuous and picturesque, in contrast to the modern menace of sensational journalism. Rosy representations of old-fashioned village gossip, like Henry’s painting, expressed the anxieties of the era over its own prying press, viewed as a threat far more extensive, potent, and dangerous than the parochial chatter of old. Historian Glenn Wallach and others have demonstrated how gossip and scandal journalism surged beginning in the mid-1870s, when the popular press began to devote unprecedented attention to aspects of Americans’ private lives, usually sordid ones, previously off-limits to public discussion. Its riveting disclosures about famous preacher Henry Ward Beecher’s adulterous affair with his parishioner Elizabeth Tilton and his subsequent trial catalyzed the first widespread critiques of the American media’s impropriety, increasing power for libel and blackmail, and disregard for the sanctity of private life. These critiques proliferated in the following decades as Joseph Pulitzer, William Randolph Hearst, and other enterprising publishers perfected the dubious art of press sensationalism, “enshrin(ing) the values that emerged from the ashes of the Beecher scandal.”9 Responding to the Beecher affair, which engulfed the headlines in 1874, an English observer bemoaning “The Abolition of Privacy” called the American reporter “the old village gossip revived on a colossal scale.” He continued that “He is more terrible in so far as it is more disagreeable to know that many hundred people are gloating over the details of your private life than to know that half-a-dozen neighbors are talking scandal. . . . On the whole, in such a case as that of Mr. Beecher, the new evil is undoubtedly worse than the old.”10 In 1884, the very same year that Henry composed The Latest Village Scandal, American intellectual John Bascom alleged, “Printed gossip is no better, but worse rather, than street gossip.” In an article on the “Public Press and Personal Rights,” he claimed, “To crave scandal is bad enough; to publish it is worse.”11

E. L. Godkin also drew a sharp contrast between the relatively harmless spoken gossip of the village and malign industrial newspaper gossip in an influential 1890 Scribner’s Magazine essay titled “The Rights of the Citizen IV. To His Own Reputation”:

The most absorbing topic for the bulk of mankind must always be other men’s doings and sayings, and it can hardly be denied that there is some substance in this apology. But as long as gossip was oral, it spread, as regarded any one individual, over a very small area, and was confined to the immediate circle of his acquaintances. It did not reach, or but rarely reached, those who knew nothing of him. It did not make his name, or his walk, or his conversation familiar to strangers. And what is more to the purpose, it spared him the pain or mortification of knowing that he was gossiped about. A man seldom heard of oral gossip about him which simply made him ridiculous, or trespassed on his lawful privacy, but made no positive attack on his reputation. His peace and comfort were, therefore, but slightly affected by it.

In all this the advent of the newspapers, or rather of a particular class of newspapers, has made a great change. 12

Of course, those victimized by village gossip had not experienced it this way, as mostly benign. For example, Jane Kamensky notes that the “heightened value” early Americans “placed on speech” had the opposite effect of making “ill words extraordinarily costly.”13 According to historian of early America Mary Beth Norton, “Reputations were sustained and lost in the early colonies primarily through gossip.” The consequences for the objects of spoken gossip could be grave and numerous: gossip invited ridicule, dashed marriage prospects, led to commercial and professional ruin, and set in motion “investigations, indictments, and punishments” for criminal conduct. People appropriately dreaded gossip; they “were well aware of their vulnerability to nasty tales.”14

But later critics believed in the escalated hazard of printed gossip, which demanded bold action from responsible citizens and the legal system. Bascom pleaded for “new customs, if not new laws” to be established as a safeguard against the “omnipresent press, breaking in on many of the amenities of social life, and scattering as news things of private interest only and of dear personal concern.”15 As a “remedy for the violations of the right to privacy” perpetrated by the press, Godkin also called for “defenses (to be) thrown by law or opinion around the reputation or privacy of individuals.”16 Only a few months after the publication of Godkin’s Scribner’s Magazine article, jurists Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis advanced the concept of “the right to privacy” for the very first time in American jurisprudence. In a legendary essay in the Harvard Law Review titled “The Right to Privacy,” they implored the legal system to defend embattled citizens against the newspapers’ unauthorized publication of their personal information. “Even gossip apparently harmless, when widely and persistently circulated, is potent for evil,” Warren and Brandeis warned. Whereas they claimed “the injury resulting from such oral communications would ordinarily be so trifling that the law might well, in the interest of free speech, disregard it altogether,” gossip’s appearance in print mistakenly imbued it with authority and unprecedented influence for ill: “When personal gossip attains the dignity of print, and crowds the space available for matters of real interest to the community, what wonder that the ignorant and thoughtless mistake its relative importance.”17

At the same time that Henry’s painting pictures the amusing oral gossip of olden times, its title slyly conjures the alternate world of sensational journalism that made village gossip so appealing to his generation. Consider the very word “scandal.” By the late nineteenth century, the term had come to signify, specifically, a “mediated event”: the exposure of unseemly behavior through the press. In Political Scandal: Power and Visibility in the Media Age (2000), John B. Thompson describes how writers in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries had used the words “scandal” and “scandalous” differently, to characterize allegations and publications deemed “libellous, seditious, or obscene.” Yet changes to the nineteenth-century press, which began as early as the late eighteenth century, created the new, modern definition of scandal as “an event which involves the disclosure through the media of previously hidden and morally disreputable activities, the revelation of which sets in motion a sequence of further occurrences.” The nineteenth century, according to Thompson, was “the birthplace of mediated scandal.”18 The historical emergence and popularization of scandal as a media phenomenon underscores how Henry’s painting anticipates the growing sensational news industry and directly positions itself as an alluring counterpoint.

Henry also playfully utilizes the term “latest” to evoke the modern newspapers. Much of the humor of The Latest Village Scandal derives from the disjunction between the calm clip of rural life symbolized by the trundling wagons and the title’s reference to the “latest” scandal, which refers to speed, newness, and efficiency—in particular, the industrial speed of newsgathering and news dissemination in 1885. In the Gilded Age, quicker printing presses, the formation of telegraphic news agencies, and new technologies such as the telephone, automatic typesetters, and halftone printing machines all “enhanced (the) capacity for swift gathering and disseminating of news.”19 Henry marveled at the locomotive pace of the modern press inconceivable to earlier generations. His archive at the New York State Museum contains a clipping Henry saved from the New York Herald titled “The Largest Press in the World” (fig. 2), which boasts about the newspaper’s newest “monster printing machine” churning out 150,000 eight-page papers every hour, at the pace of 2,500 pages per minute. The machine “concentrated the achievements of a hundred years” and represented the “crowning triumph” of a long history of invention, from the first hand-operated press to the rotary press (invented by the millionaire Robert Hoe, who was an early purchaser of Henry’s work) to the Goss press. The printer was as large as a “locomotive” and as fast as an “express train,” accelerating “the spread of intelligence and news” to a velocity “never dreamed of” before.20 Other publishers imagined themselves as express trains. A cartoon by Homer Davenport (1867–1912) for Hearst’s Journal titled “And the Train Went By” (fig. 3) characterized that paper as a steam engine hurtling past its rivals, including caricatures of Pulitzer as an idle farmer and Charles A. Dana as a pursuing pooch. The cartoon’s rustic setting vaunted the reach of the “new journalism” to remote areas, which was made possible by a complicated distribution system involving an expanded postal service and new transportation infrastructure such as the transcontinental railroad. For example, news outlets hired “special” or “fast” trains to race Sunday papers from New York City across the country.21 Whereas Davenport’s “new journalism” roars from background to foreground instantaneously, conquering the temporal and spatial distance separating the source of news from the viewer, its implied recipient, the rutted roadway of The Latest Village Scandal, communicates the plodding and laborious nature of spreading scandal in earlier times.

A major boon of faster presses was that they enabled the New York Herald and its competitors to provide readers with the very “latest” news in a torrent of up-to-date editions issued throughout the course of a single day. By the early 1870s, some evening papers produced four distinct editions, at one, two, four, and five o’clock in the afternoon. On special occasions, papers were produced every hour until late in the night, amounting to up to nine or ten issues per day. Every edition blared a new, more “timely” banner headline, touting the latest possible news.22 Newsboys swarming the city streets also attracted customers day and night with the familiar cry of “latest news!” In Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889), a medieval newsboy hawks copies of the Camelot Weekly Hosannah and Literary Volcano! with the exclamation, “latest irruption—only two cents—all about the big miracle in the Valley of Holiness!”23 Like The Latest Village Scandal, an illustration by Daniel Carter Beard (1850–1941) of the newsboy as a fleet-footed herald (fig. 4) reimagines a slower era of news dissemination through the Victorians’ exhilarating encounter with the “latest” news.

As the news cycle dramatically accelerated, a common critique was that the breakneck tempo of news gathering and reporting scuttled responsible journalism. Many felt that the race of the papers for scoops had eclipsed their critical function. A writer for The American called the increasing ideal of newspaper work since James Gordon Bennett Sr. (founder, editor, and publisher of the New York Herald) “getting a ‘scoop’ . . . [t]hat consists in publishing a bit of sensational news before any rival can get hold of it, and the important point is not whether the news has any value, but whether it is exciting and the enterprise of competitors is beaten.”24 Another critic bemoaned the decline of journalism that educated and elevated public opinion. “To satisfy the craving for speed is the object of the journalist’s ambition. . . . It is not wit, not wisdom, not humor, not clear thought and balanced ideas, that the journalist is ambitious of supplying.”25 Gossip and scandal thrived in the vacuum left by intelligence, reason, and judgment. By comically referring to the latest scandal in a tableau of sluggish spoken gossip, Henry’s painting gestures towards these reproofs.

Harvesting Gossip

The Latest Village Scandal was displayed at several major exhibitions, including the National Academy of Design annual of 1886 and the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889; however, few contemporaneous reviews of the scene survive.26 One comes from the auction catalogue for the American Art Association’s sale of the paintings of banker, philanthropist, and collector George Ingraham Seney, which took place after his death in 1893:

A farmer, driving his wife and baby on a visit, meets on a road which descends a hill a neighbor who is returning from the grist mill. Each pulls up to exchange salutations, and the neighbor relates the latest gossip of the village, which he has acquired upon his visit to the mill. The family man listens with an undisguised grin to the petty scandal, while even the expression of severity which his wife assumes does not conceal the interest she takes in the narration.27

Several details support this narrative of a wayside encounter en route from the village mill. The palette of burnt umbers and oranges indicates harvest season. A lumpy sack stowed in the gossip’s buckboard bulges with grist ground to meal or flour. Nineteenth-century writers also liked to recall the convivial days when villagers gathered in mills to swap stories and collect news of the day while awaiting the work of the stone.28 One described how “(i)t was often the habit of the customer if his grist was a small one and he had two or three miles to go to mill, to wait for his grain to be ground that he might take it back home with him. Then perhaps he would meet there two or three of his neighbors with similar intentions and this gave them an opportunity to talk and gossip over the affairs of the neighborhood and this made the mill a sort of rendezvous to hear and impart local news and happenings of the time.”29 In an article on the history and modern uses of windmills, engineer and professor Robert Henry Thurston also called the miller “an authority on local as on national politics, village gossip, and the news of the day.”30 There was truth to the perception of mills as social hubs and gossip rendezvous. As early as 1804, an agriculturalist had invoked Richard B. Sheridan’s play The School for Scandal in calling gristmills “the schools of parochial scandal” in a treatise on estate management.31

To Thurston, a specialist in steam power, wind- and water-powered mills were icons of a romantic but endangered past, disappearing with the rise of steam power. It “calls up much of romance and interesting and impressive history,” he wrote of the windmill, “and the true artist finds place for it in many a rustic scene.”32 Village mills held a central place in the historical imagination of late nineteenth-century American artists and audiences. Currier and Ives prints such as The Roadside Mill (1870) and Winter in the Country, The Old Grist Mill (1864) were immensely popular. The Old Mill (1876, fig. 5) by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823–1900) also attracted wistful crowds when it was exhibited at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. The painting pictured the Sanford gristmill nestled peacefully on the Wawayanda Creek near Warwick, New York. Its roofline blends into the forest canopy, and its palette repeats the autumnal tones of the plant and animal life encircling the building, entailing a harmony between man and nature. A flirtatious couple conveys the social cohesion and romance of village life centered on the mill. The setting sun bathes the scene in a celestial glow that implies divine sanction, while elegizing the agrarian way of life in its twilight by the 1870s. Henry’s mill imagery summoned a serene and untroubled past resembling Cropsey’s rural fantasy.

However, viewers may have also read such imagery as a distant echo of contemporary media practices closely associated with milling in the popular vernacular. Read from a different vantage point, in relation to gossip and scandal, The Latest Village Scandal’s allusions to the mill visually pun on modern expressions like “gossip mill,” “scandal mill,” and “rumor mill.” These epithets entered common parlance not in the preindustrial era of gristmills but at the end of the nineteenth century, when they frequently referred to modern journalism (the Oxford English Dictionary dates the first usage of “rumor mill” to an article in the New York World in 1888, although there are earlier examples of these expressions). The action of the mill described how the papers methodically churned out scandalous stories while grinding down the reputations of prominent persons like grist to the stone. The mill’s invocation of America’s utopian agrarian origins set up an implicit contrast with the modern industrial culture of scandal to pose a stirring picture of national decline. When presidential candidate Grover Cleveland was accused by a Buffalo newspaper of fathering a child out of wedlock, in one of the first political sex scandals in American history, an 1884 article in Harper’s Weekly lamented the publication of “stories containing gross charges” against the Democrat: “There seems to be a regular scandal mill here, from which the most revolting stories are sent forth,” it quoted a local Cleveland supporter.33 In Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, We and Our Neighbors (1875), published as the Beecher-Tilton trial became first-page and daily news, a character complains about the “four or five big dailies running the general gossip-mill for these great United States.”34 Deployed by press critics unnerved by the scandals plaguing prominent men such as Beecher and Cleveland, expressions like “gossip mill” and “scandal mill” lend a menacing undertone to Henry’s painting of old-fashioned village gossip.

The painting’s related theme of the harvest may also register language critiquing the cultivation of gossip by the newspapers. Again, the harvest’s various stages succinctly captured the workings of the press while invoking the bucolic past to imply societal decline. Warren and Brandeis unspooled an evocative analogy between the modern media and the grower and reaper in a memorable passage from “The Right to Privacy”:

Gossip is no longer the resource of the idle and of the vicious, but has become a trade, which is pursued with industry as well as effrontery. To satisfy a prurient taste the details of sexual relations are spread broadcast in the columns of the daily papers. . . . Each crop of unseemly gossip, thus harvested, becomes the seed of more, and, in direct proportion to its circulation, results in a lowering of social standards and of morality.35

Warren and Brandeis’s harvest metaphor is elaborate and nuanced. The action of sowing seed modeled the way the papers broadly diffused or “spread broadcast” intimate news over vast terrain. The original meaning of the term “broadcast” was to scatter seeds widely instead of sowing them in drills or rows. Prefiguring the future radio and television applications of the term, however, Warren and Brandeis describe the expanding dissemination of news by the newspapers as a “broadcasting.” The work of reaping and selling crops also captured the practice of newspapers of collecting personal information, then retailing it as a commodity in the burgeoning market for private and tawdry news. The perennial cycle of the harvest, the way germ begets germ, and old crop yields new crop, resembled the way that newspaper gossip continually fed the public appetite for more, generating the continuous cycle of information propagation and consumption. Warren and Brandeis further derided the morally corrupting influence of this “crop of unseemly gossip” in agricultural terms, as a blight invading the minds of the reading populace: “Triviality destroys at once robustness of thought and delicacy of feeling. No enthusiasm can flourish, no generous impulse can survive under its blighting influence.” They characterized printed gossip as a pestilence invading society at large, writing “(n)or is the harm wrought by such invasions confined to the suffering of those who may be made the subjects of journalistic or other enterprise.”36 Printed gossip multiplied endlessly the first intrusion it practiced on the individual object of talk.

“Visual Gossip”

Warren and Brandeis’s description of gossip journalism as a plague afflicting the American populace, including the objects and writers and readers of gossip, raises an intriguing question about The Latest Village Scandal. Who or what is the subject of the painting’s salacious chatter? The actual scandal at the heart of the painting, and its cast of actors or malefactors, remains ambiguous. Karen Zukowski has written that the vagueness of the painting title “encourages viewers to concoct their own versions of these country folks’ conversation,” or to speculate about different possible explanations for the scandal.37 Viewers of Henry’s painting would have imaginatively discussed and debated the scandal’s tantalizing significance. Who did what? To whom? When, and how?

Owing to its scent of scandal and purposeful, enticing indeterminacy, we might compare The Latest Village Scandal to the genre of the “problem picture” popular in Britain from the 1890s to the 1910s, although select canvases were also reviewed and reproduced in America. Problem pictures by artists such as John Collier (1850–1934) and William Frederick Yeames (1835–1918) depicted highly charged moments within enigmatic narratives reminiscent of contemporary scandals and other media events capturing the public’s imagination in the press. Such ambiguity generated lively conversation among art audiences at exhibitions and in the pages of papers and periodicals, speculating about the experiences, motives, emotions, and morals of the painted characters, as if they were real players in an unfolding scandal. In her work on problem pictures, art historian Pamela Fletcher writes that these speculative readings “move(d) aesthetic response into the realm of gossip,” and she therefore calls the problem picture a form of “visual gossip” that actively participated in the era’s culture of scandal and sensation.38 Painted at the dawn of the sensational press, The Latest Village Scandal also compelled viewers to partake in visual gossip, by inviting them to decipher the eponymous scandal. Although no specific interpretations of the scandal appear to survive in written reviews of the painting, we can imagine Henry’s viewers chattering about the lives of his villagers as would the village gossip or the sensational press.

What narratives, then, might Henry’s viewers have invented for The Latest Village Scandal? The painting’s imagery suggests at least one possible plotline, related to recent scandalous headlines. Consider more closely the party encountering the gossip. The woman’s aggressive scowl may telegraph not merely disapproval of the misdeeds of her neighbors relayed by the gossip but outrage directed at the gossip himself. Authors had long counseled readers, especially women, to scorn the loose-lipped spreaders of scandal. Other details indicate that the gossip poses a direct and personal threat to the woman and her family. His wagon wheel casts a menacing shadow in the shape of a pitchfork aimed to skewer the family group. A brewing storm portends danger, as does the act of stopping in the roadway to chatter. One critic noted that Henry’s painting showed “two vehicles met in a dangerous place on the hill side and remaining stationary while their occupants, regardless of the peril, detail the most recent gossip of the neighborhood.”39 Also note the woman’s protective grip on her rollicking baby, as well as her husband’s clownish and unwitting demeanor. These cues subtly suggest sexual infidelity and even a bastard child as grist for the gossip’s mill. Such a prurient reading may seem farfetched now, but it would have been immediately available to Henry’s generation, much more so than to our own, since the “latest scandal” of the mid-1880s converged on the scintillating matter of a sexual affair and illegitimate baby.

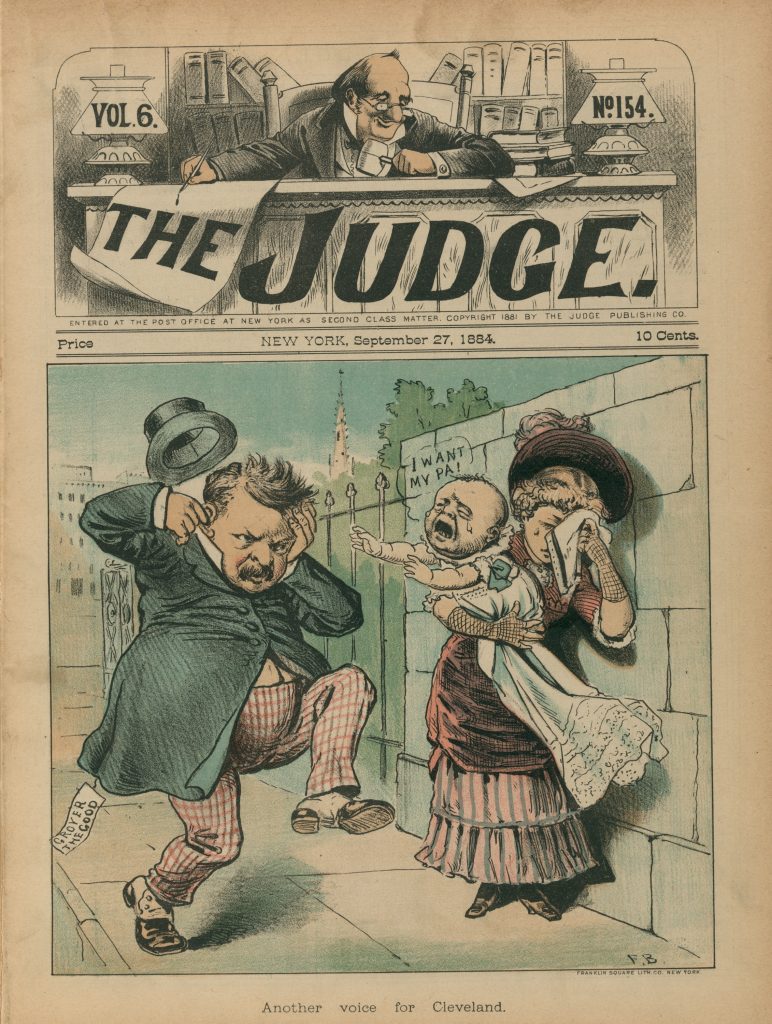

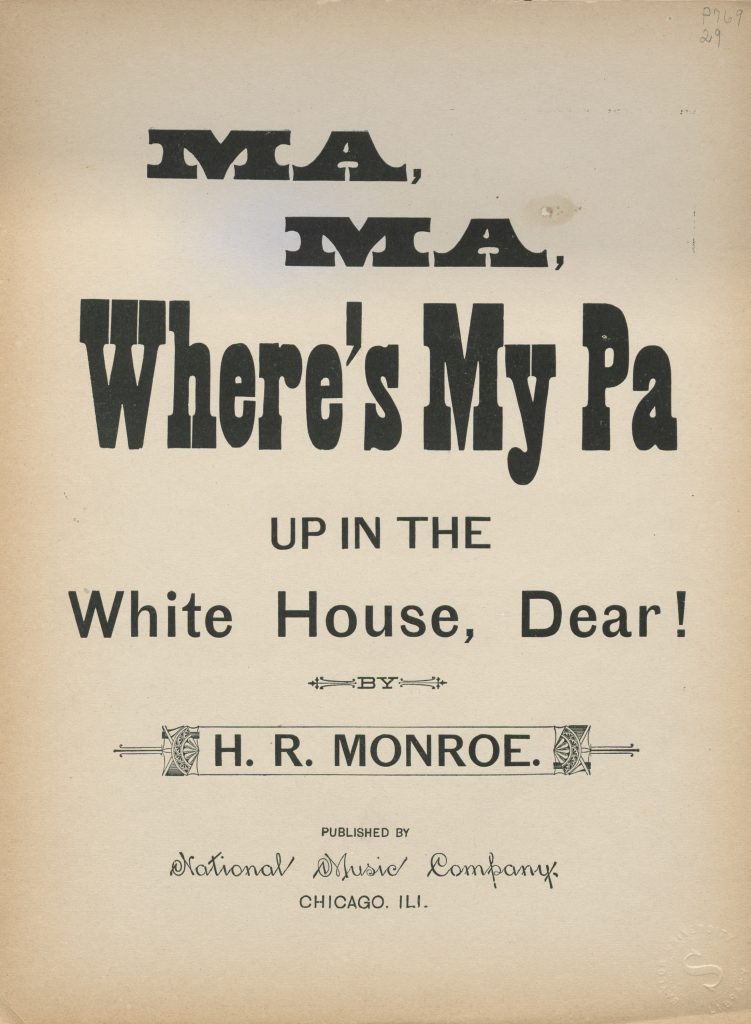

In the summer and autumn of 1884, exactly as Henry painted the first version of The Latest Village Scandal, papers nationwide overflowed with stories accusing Grover Cleveland of fathering an illegitimate son. On July 21, just ten days after Cleveland won the Democratic Party’s nomination, the Buffalo Evening Telegraph carried a front-page article claiming that years earlier Cleveland had seduced a local shopgirl named Maria Halpin and revoked his promise of marriage, although she bore him a son. Eventually Cleveland employed villainous detectives to forcibly commit Halpin to an insane asylum and toss her child into a local orphanage.40 The “Terrible Tale” became a national sensation during the election season. Cleveland’s campaign was pressed to admit to the illicit relationship, although it also characterized Halpin as a harlot and questioned the paternity of the boy. As the Cleveland-Halpin scandal gripped the reading public, concern for the abandoned infant became a cause célèbre. In a famous cartoon on the September cover of the popular humor magazine Judge, illustrator Frank Beard (1842–1905) caricatured the exasperated president, spurned mistress, and forsaken baby, wailing, “I want my Pa!” (fig. 6). The image recycled a popular campaign chant devised by Cleveland’s opponents: “Ma, Ma, where’s my Pa?” Republican operatives also pushed carriages containing baby dolls in parades and rallies.41 Even sheet music was written about the “Poor Little Tom Tid” who “cried for his daddy in vain” (fig. 7). Henry must have relished the saga of the Cleveland baby, both titillating and pitiable, as an avid reader of newspaper sensations.42

“The Gossip of History”

Henry was a voracious consumer of newspaper scandal. His scrapbooks contained smutty stories snipped from the pages of outlets including the New York World and New York Herald. His early biographer Elizabeth McCausland noted Henry’s sundry and frequently unseemly sources of amusement when she described, “The demolition of old buildings, murders, divorce cases . . . are some of the subjects which interested Henry sufficiently so that he saved clippings on them.”43 He followed the twists and turns of sensations closely. A notable case is that of society belle Mrs. Fayne Moore, who along with her husband attempted to extort cash from the well-to-do proprietor of New York’s New Amsterdam Hotel in 1898. Features on Moore’s highly publicized trial, one illustrated with a magnetic portrait of “Pet Strahan” (fig. 8), as Henry’s handwritten notations and the papers referred to her, survive in the artist’s archive.44 Another clipping reports Robert B. Van Cortlandt’s suicide by slashing his wrists in his antique home, Guard Hill, in Old Bedford Village, New York, an incident that combined Henry’s dual interests in early American houses and contemporary scandal.45 Two tintypes of Henry in costume (fig. 9), likely staged as studies for an unknown historical genre painting, hint at the artist’s exuberant embrace of such media entertainments. They show the artist reading a newspaper, with his legs cantilevered atop another edition crackling over the crest rail of an empty cane chair. He puffs on a cigar and sports the tall top hat popular in the first half of the nineteenth century. His engaged looks in either direction suggest a social setting, recalling the days when newspaper reading was primarily a public activity performed in the course of discourse and debate on current events in the post offices, taverns, and inns of the early Republic.46 However, the artist’s ease and irreverent lack of etiquette also connote the feeling of empowered enjoyment that Henry likely derived from reading the later sensational news.

Additional clippings in Henry’s scrapbooks on colonial and revolutionary subjects suggest that he also took a deep interest in popular historical writing that resembled gossip journalism. One example is a New York Herald article from 1901 that Henry preserved for source material, titled “Christmas at Mount Vernon when George Washington was Alive” (fig. 10). Commanding the page is a spirited portrait of the stoic president striking the unexpected pose of a society host, a dazzling nabob decked in ruffs and frills. As he raises a twinkling goblet of madeira to toast his party, Washington’s usual square jaw slackens into a welcoming grin. “The Father of His Country, who from a present day standpoint stands always on a pedestal, knew how to unbend from his accustomed dignity and take graceful part in the merry-making,” the article revealed.47 Encircling Washington are photographs of the south side of Mount Vernon’s façade and the home’s well-appointed period rooms, where his bountiful holiday fêtes transpired. There are clear parallels with newspaper items divulging the home lives of modern day elites, such as an article featuring “Photos of Children of the Rich,” which Henry also saved (fig. 11).48 The bold headline and lavish layout of the Washington article, its descriptions and illustrations of the home life of a socially prominent person, and its overall framing of society life as simultaneously exclusive and accessible to the reading public, echo the gossip columns. Its focus on the sumptuous interior of Mount Vernon and the president’s generous banquet smacks of newspaper items on society entertainments, including the masquerade balls hosted by fashionable New Yorkers, where historical costumes such as Washington’s fancy dress were always in vogue (fig. 12).

The Washington feature exemplified a new brand of historical writing that commentators explicitly connected to gossip and gossip journalism: social history. Bucking the long tradition of historical scholarship that recounted public events and the public deeds of great men, a new generation of historians in the mid- to late nineteenth century began to approach the past from the perspective of the domestic, “reshap(ing) the narrative of America’s past to include private spaces of home and family.” 49“Domestic history,” to use the period term, emphasized the private realm of everyday life, such as Washington’s home life, to convey a more vivid, humanized, and authentic account of the lives of America’s ancestors. Whereas previous writers had analyzed the actions of historical figures recorded in official documents, domestic historians turned to unpublished private letters and diaries and the warm recollections of descendants, in search of more personal and affecting information. An early champion of this mode was Benjamin Bussey Thatcher. In a review of James Thacher’s history of Plymouth, Thatcher likened its trivial details of everyday life to “the gossip of history,” although he defended their inestimable value to the historian seeking to enliven the past:

All this, indeed, may be the gossip of history. Yet who would be willing to part with it? Who does not see that it pours a flood of light on the character of the men, and on the condition of the times? Who does not perceive, that it is the multitude of trifles, like these, which make up the life of the volume? Would there were more of them! How should we rejoice over the discovery of the private journal of Standish, for example,—had that worthy been so obliging as to keep one; or of Elder Brewster, or the handsome John Alden himself.50

However, more conventional historians likened such accounts of the private lives of America’s ancestors to gossip and gossip journalism in less forgiving terms. One flashpoint for these dueling models of historical writing was the bestselling history of prominent men and women in the colonial and revolutionary eras, Through Colonial Doorways (1893), by the Philadelphia writer Anne Hollingsworth Wharton.

In the preface, Wharton began: “To read of councils, congresses, and battles is not enough: men and women wish to know something more intimate and personal of the life of the past, of how their ancestors lived and loved as well of how they wrought, suffered, and died. With some thought of gratifying this desire, by sounding the heavy brass knocker, and inviting the reader to enter with us through the broad doorways of some Colonial homes into the hospitable life within, have these pages been written.” The frontispiece (fig. 13) depicted an elegant colonial dame graciously welcoming a visitor into her stately abode. A magnificent hat obscures the caller’s face, allowing the reader to imaginatively identify with the anonymous houseguest, who is offered a privileged view into the hostess’s genteel domestic world. With titles that parroted modern society headlines such as “New York Balls and Receptions,” the proceeding chapters highlighted “the informal intercourse” of the homes of the era’s grand women and provided intimate “glimpses of their husbands and lovers, the warriors, statesmen, and philosophers of the time, at some social club” like Cambridge’s Hasty Pudding or the Delphian Club in Baltimore. “Meeting them thus, enjoying witticisms and good cheer in one another’s excellent company,” Wharton wrote, “we feel a closer bond between their life and our own than if they were always presented to us in public ceremonial or with pen and folio in hand.”51 Her claim that domestic history could uniquely draw modern readers closer to history’s great men and women recalled Pulitzer’s claim that personal journalism about notable men “will bring him more clearly home to the average reader than would his most imposing thoughts, purposes, or statements.”52

Such connections alarmed a critic for The Nation:

Readers in whom the last remnant of good taste has not been destroyed by the customs of contemporary journalism, have learned to turn a deaf ear to invitations to invade the privacy of domestic interiors and hear intrusive gossip concerning the affairs of their inmates. When, however, they are invited, as in the present volume, to an “At Home” of the stately entertainers of ceremonious colonial days, it seems but reasonable to expect that instead of gossip there shall be picturesquely illustrative anecdotes, and in place of inventories of the ladies’ silks, satins, and jewels, chronicles of gracious speech and finished deportment. A measure of familiarity, gained from the fiction of Thackeray and Hawthorne or the soberer pages of essayists, most readers already have with the times when our country’s manners still preserved something of an old-world courtliness. To their store of such literary reminiscences all would gladly add others of like quality.

Unfortunately for expectations of better things, what is here actually shown through colonial doorways is too much of a feather with what the public at the heels of the reporters sees through modern doorways.53

What was shown through colonial doorways resembled too closely the gossip of contemporary reporters. The connection was all the stronger, since many of the colonial families that Wharton discussed remained fixtures in the modern society pages. Wharton herself admitted, “How the old names repeat themselves in the social life of to-day!”54

Historian Elizabeth F. Ellet also faced similar scrutiny and was someone whom Henry greatly admired. He even based his 1871 painting Drafting the Letter (fig. 14) on Ellet’s description of a little-known incident in the life of Philadelphian Elizabeth Graeme Ferguson, from her two-volume history The Women of the American Revolution (1848). Published nearly half a century before Wharton’s text, Ellet’s groundbreaking history introduced women’s lives as valid historical subject matter. However, a review of a later edition in the New York Times belittled her contribution as “a volume of reference as to ‘who was who’ in Revolutionary days,” showing “no real effort at serious biography in any of the sketches.”55 Ellet’s account of the lives of presidents from Washington to Grant and their leading ladies, titled The Court Circles of the Republic, or the Beauties and Celebrities of the Nation (1869), was also criticized as historical gossip. One critic wrote that Ellet’s book “will interest all lovers of gossip and biography,” although “we think she has drawn too much from the newspaper accounts of balls and parties at Washington.”56 Today Ellet is best remembered as a gossip not for her writings, but for her role in circulating a rumor about Edgar Allen Poe’s love affair with Frances Osgood, which enraged the pair.57 Yet the domestic histories of Ellet, Wharton, and their peers were likened to gossip and gossip journalism.

Given that Henry mined domestic histories for subject matter, it should not be surprising that certain qualities of his art emulate gossip and gossip journalism, as well. Put another way, although Henry’s practice may seem far removed from gossip, there are close connections between the two. Return, for example, to Drafting the Letter. According to Ellet, Ferguson had hoped to end the revolutionary war speedily by relaying to American colonel Joseph Reed the offer of a British bribe in exchange for his surrender. The colonel spurned her overture and on July 26, 1778, Ferguson received a copy of Towne’s Evening Post decrying her involvement in the war. Henry’s painting shows her at her home, called Graeme Park, as she seals a letter to Reed castigating him for allowing the newspaper to libel her as a tool of the British. The newspaper is tossed aside on the floor, framing Henry’s scene as a more revealing and private account of Ferguson’s life than the public image portrayed by the paper. Henry’s attention also shifts from Ferguson to the highly detailed environment of her home, which Henry attempted to replicate from visits to Graeme Park and by populating the interior with objects drawn from his own collection of period furnishings. Amy Kurtz Lansing has suggested that these features of the canvas emulated Ellet’s methodology, meaning the insistence on “authenticity” and the “sentimental tone” she imparted through “descriptions of each heroine’s charms rather than a litany of names and dates.”58 But by emphasizing the private life of Ferguson and the details of her domestic surroundings, Henry’s work also approaches the content and narrative strategies of gossip.

The same may be said of numerous “domestic history” paintings by Henry, including The Lafayette Reception (1874; Cliveden, A National Trust Historic Site) and A Wedding in the Thirties (1885; Philadelphia Museum of Art). Depicting receptions at the stately houses of yesteryear, both extend the modern viewer a metaphorical invitation to witness the homes’ “informal intercourse,” in Wharton’s words. Unlike Ellett and Wharton, however, charges of gossipmongering were never leveled at Henry. This may be because his subjects were often imaginary rather than specific historical personages, as in A Wedding in the Thirties. Other paintings Henry completed for his subjects’ descendants; Samuel Chew III commissioned The Lafayette Reception, which showed Benjamin Chew, Jr. entertaining the Marquis de Lafayette at the family’s Philadelphia estate in 1825. Henry’s masculinity also likely immunized him against any association with gossip, usually gendered as feminine. Yet Henry’s art shared its interest in the private lives of social elites with domestic historians and the period papers alike.

“The Unfortunate Exposé”

Henry’s clientele, a cadre of socially prominent New Yorkers, typically had a more complex and less positive perspective on gossip journalism. According to Maureen Montgomery, the upper crust of Gilded Age society was largely dependent on flattering publicity to consolidate their social power in the eyes of the public. Montgomery demonstrates how many high society men and women aided and abetted the public interest in their lives by flatly courting media coverage. However, their prominence also made them uniquely vulnerable to invasions of privacy and accusations of scandal, leading them to especially fear and denounce sensational journalism. “In truth, it was difficult to simply ‘switch publicity on and off.’”59

The danger that unwelcome publicity posed to Henry’s patrons is evident in a social register that he retained until his death. Titled The “400.” (Officially Supervised) (fig. 15) and published by The Melville Company in 1890, the booklet offered Henry a list of deep-pocketed buyers to whom he could potentially market his art: written from the perspective of an anonymous insider, it indexed the 617 most prominent men and women of New York City, revising the famous assessment of Ward McAllister, arbiter of New York social life, that there were exactly four hundred individuals whose ancestry and breeding gave them claim to belong to the fashionable set, or so-called “society.” The roll of names that followed—including the Schuylers, the Astors, and the Vanderbilts—formalized the exclusive inner sanctum of society. However, the dangers of belonging to an “exclusive set” are revealed by a publisher’s note at the back of The “400.,” which claims that “a memoranda of the principal writers upon our great Metropolitan newspapers” is in preparation, “together with information [on] how to get matter into, and how to keep it out of newspapers.”60 One prominent New Yorker who came out on the wrong side of this Faustian bargain between fawning and fickle coverage was George Ingraham Seney, who purchased The Latest Village Scandal from Henry shortly after falling victim to newspaper scandal.

Born on Long Island in 1826, the son of a Methodist minister, Seney rose steadily through the banking world of New York City to become president of the Metropolitan Bank in 1877. He also invested heavily in railroad development and speculation. Seney freely watered stock as he and several other investors acquired control of major lines including the East Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia Railroad and the Richmond and Danville Railroad. In the classic memoir Twenty-Eight Years in Wall Street (1887), Henry Clews called Seney’s schemes “entirely novel in the history of Wall Street”:

Instead of starting with moderate issues in amount, as has usually been the custom of most men handling railroad and telegraph properties, and doing the watering process by degrees, Mr. Seney boldly began the watering at the very inception of the enterprise, pouring it in lavishly and without stint. There was nothing mean or niggardly about his method of free dilution, the sight of which threw some of the old operators into a fit of consternation. The stocks were strongly puffed, and as they were so thoroughly diluted their owners could afford to let them get a start at a very low figure. The future prospects of the properties were set forth in the most glowing colors, the public took the bait, and the stocks became at once conspicuous among the leading active fancies of the market.

The cause of the vigorous life and amazing activity so suddenly imparted to the stocks of the Seney Syndicate can only be revealed by a careful perusal of Mr. Seney’s checkbook, which, if still in existence, will show commissions paid for the execution of the orders to buy and the orders executed to sell, both by the same pen and in the same handwriting.61

The initial result of Seney’s machinations was a windfall for the wily financier. “(F)rom being almost one of the poorest men in Brooklyn, he soon became marked as the richest,” wrote Clews.62 Through gifts to Wesleyan University, the Long Island Historical Society, the New York Methodist Hospital (originally Seney Hospital), and other charities, Seney “came prominently before the public” as a generous benefactor.63 Moreover, he courted positive media attention through his philanthropic activities. The Boston Sunday Herald noticed that Seney gave away money “in a splurgy way, and the affair was certain to find its way to the newspapers in an hour after the check had been drawn.”64

However, the panic of May 1884 rapidly gutted Seney’s fortune and scandalized his reputation. Seney had speculated with Metropolitan Bank funds, making it vulnerable to falling share prices. His imprudent loans and investments caused the bank to collapse in mid-May. He resigned and immediately forfeited more than one million dollars’ worth of personal assets to the bank, including his Brooklyn home and his vast collection of paintings, which were sold at an American Art Association auction in late March and early April of 1885 to pay off the debt. The bank would recover, and Seney would eventually earn a new fortune and return to collecting, purchasing The Latest Village Scandal, among other compensatory acquisitions of the late 1880s and early 1890s. But Seney would never regain his former public stature, irreparably tarnished by newspaper scandal.

In May 1884, there were “sharp things published about bank presidents who were of a speculative turn and interested in railroads as promoters, and they all pointed to Mr. Seney and the roads of the Seney syndicate.”65 A scathing front-page feature in the Sunday supplement of the New York World (fig. 16) contained a portrait sketch of Seney and twelve other “Wall Street Celebrities” said to be responsible for the crash. Based on a studio photograph, Seney’s likeness emphasized his dignified bearing. Yet the text unveiled the hidden chicanery lurking beneath this correct public façade. Of Seney’s underhanded malfeasance, the paper wrote, “With one hand he scattered donations on all sorts of charitable institutions and with the other took the funds of the Metropolitan National Bank, of which he was President, to speculate in Southern stocks and land. . . . [H]is operations compelled the Metropolitan Bank to close its doors.”66 Another article on “Gossip Concerning Blue Wednesday in Wall Street” in The Boston Sunday Herald claimed that “Bro. Seney had two sides—his Sunday side and his every day side. The former led him to give away with unparalleled generosity the money which the latter enabled to make.” The latter, though, led him to be “the author, if not the finisher, of a system of railroad operation, which . . . morally strikes the casual observer as decidedly thin and tenuous.”67 Others felt shades of pity for the once illustrious banker, now bled of his fortune and held up to public scorn and ridicule. Clews himself sounded a note of regret: “It would seem that Mr. Seney at one time aspired to be a great philanthropist, and had it not been for the unfortunate exposé which was the result of the panic, he might one day have stood in as high and lordly a position as the renowned Peabody, with even a greater reputation as a financier.” Clews concluded that “It is the winding up that tells the tale and exposes the duplicity of the ablest financiers, who vainly imagine that dishonest methods will always prevail.”68

The toll that scandal and insolvency exacted personally on Seney can be gleaned from descriptions of his behavior following the crash. One paper described him as “suffering, from nervous prostration.”69 Another observed, “He is said to be very much cast down, as his manner on the street would seem to indicate. He is rather a small man, and ordinarily walks with a brisk, quick step, conveying the impression of a man thoroughly satisfied with himself, and conversant with affairs, needing no help from anybody, and quite competent to deal with his present and the future. Now he walks with less erect port, and the drawn corners of his mouth indicate the trouble on the old man’s mind.”70 Scandal and misfortune contorted Seney into a broken shadow of his former self.

In light of this bruising period in his personal and public lives, we should question what attracted Seney to The Latest Village Scandal. By displacing and rendering laughable his own experience with scandal, perhaps the canvas helped to allay its damaging psychological toll. Whereas Henry enjoyed and even emulated some of the sensational matter he encountered in the press, his painting addressed itself most directly to the interests of a patron and a social class increasingly wary of newspaper gossip and scandal, as a balm for their fears and emotional injuries. The sheer number of canvases in Henry’s oeuvre that returned to the comforting subject of village tattle—including Food for Scandal (or Gossips) (1907; Private Collection), The Gossips (1908; whereabouts unknown), and The Village Tavern (or Telling of the Latest Sensation) (n.d.; whereabouts unknown)—suggest the enduring appeal of this imagery to his sponsors.71 According to the artist’s wife, Frances Livingston Wells, Edward Lamson Henry “always tried to give some deeper meaning to a painting than to show just a pleasing picture.”72 Beneath The Latest Village Scandal’s comic panorama of neighborly gossip is a complex reckoning with the modern culture of sensationalism. Henry’s painting offered Seney and his cautious, battered consumers a reassuring vision of innocent village banter, born of profound anxieties about the modern mass media and nostalgia for a rapidly vanishing world.

Cite this article: Nicole J. Williams, “‘A Kind of Traveling Gazette’: Edward Lamson Henry’s The Latest Village Scandal, Gossip, and History at the Dawn of Sensational Journalism,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 2 (Fall 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1656.

PDF: Williams, A Kind of Traveling Gazette

Notes

- Royal Cortissoz, “Edward L. Henry and Some Others,” New York Herald Tribune, April 26, 1942, E8. ↵

- Henry frequently painted the same image twice or made slight variations on a common theme. Dated 1884, the first canvas was slightly larger but compositionally identical to the later version. The two separate paintings are cited in Karen Zukowski, “Edward Lamson Henry,” in Paris 1889: American Artists at the Universal Exposition, ed. Annette Blaugrund (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts; New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989), 257. ↵

- Henry Adams, History of the United States During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, Vol. 1 (1889; reprint, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1909), 56. ↵

- David H. Flaherty, Privacy in Colonial New England (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1972), 104. ↵

- Francois André Michaux, Travels to the West of the Alleghany Mountains, Vol. 3 (London: D. N. Shury, 1805), 248. ↵

- Washington Irving, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. (1820; reprint, New York: G. P. Putnam, 1859), 423. Partially quoted in David J. Seipp, The Right to Privacy in American History (Cambridge: Harvard University Program on Information Resources Policy, 1978), 5. ↵

- Janna Malamud Smith, Private Matters: In Defense of the Personal Life (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1997), 86. On page 92, Smith also asserts that the typical reader of media gossip “has no personal relationship that might temper knowledge and provide context” and that although oral gossip “invades privacy” to a degree, “it also preserves it by specifically avoiding public declamation.” ↵

- Edward J. Bloustein, “Privacy as an Aspect of Human Dignity: An Answer to Dean Prosser,” in Philosophical Dimensions of Privacy: An Anthology, ed. Ferdinand David Schoeman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 173. Partially quoted in Seipp, The Right to Privacy in American History, 6. ↵

- Glenn Wallach, “‘A Depraved Taste for Publicity’: The Press and Private Life in the Gilded Age.” American Studies 39, no. 1 (Spring 1998): 53. For more details on the Beecher-Tilton Scandal, see Richard Wightman Fox, “Intimacy on Trial: Cultural Meanings of the Beecher-Tilton Affair,” in The Power of Culture: Critical Essays in American History, ed. Richard Wightman Fox and T. J. Jackson Lears (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 102–32. ↵

- “The Abolition of Privacy,” The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science, and Art, August 29, 1874, 268. Partially quoted in “Contemporary Sayings,” Appleton’s Journal 12, no. 289 (October 3, 1874): 447–48. The critic referred specifically to “the interviewer.” ↵

- John Bascom, “Public Press and Personal Rights,” Education 4, no. 6 (July 1884): 610–11. ↵

- E. L. Godkin, “The Rights of the Citizen. IV.—To His Own Reputation,” Scribner’s Magazine 8, no. 1 (July 1890): 66. ↵

- Jane Kamensky, Governing the Tongue: The Politics of Speech in Early New England (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 48. ↵

- Mary Beth Norton, Founding Mothers and Fathers: Gendered Power and the Formation of American Society (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996), 253–54. Most infamously, local gossip played a major role in fueling accusations of witchcraft and diabolism. John Putnam Demos has written, “The story of witchcraft in early New England spotlights very sharply the power of local gossip. Behind the court proceedings . . . one invariably finds a thick trail of talk.” John Putnam Demos, Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England (1982; reprint, New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 246. For more on gossip in colonial America and the early Republic, see When Private Talk Goes Public: Gossip in American History, ed. Kathleen A. Feeley and Jennifer Frost (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014); Terri L. Snyder, Brabbling Women: Disorderly Speech and the Law in Early Virginia (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003); Robert Blair St. George, “‘Heated’ Speech and Literacy in Seventeenth-Century New England,” in Seventeenth-Century New England, ed. David G. Allen and David D. Hall (Boston: University of Virginia Press for the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1984), 275–322; Mary Beth Norton, “Gender and Defamation in Seventeenth-Century Maryland,” The William and Mary Quarterly 44, no. 1 (January 1987): 3–39; and Joanne B. Freeman, “Slander, Poison, Whispers, and Fame: Jefferson’s ‘Anas’ and Political Gossip in the Early Republic,” Journal of the Early Republic 15, no. 1 (Spring 1995): 25–57. ↵

- Bascom, “Public Press and Personal Rights,” 604–5. ↵

- Godkin, “The Rights of the Citizen,” 67. For Godkin’s beliefs that private life merited protection against excessive publicity, and that the popular press was more damaging than oral gossip, see also E. L. Godkin, “Libel and its Legal Remedy,” The Atlantic Monthly 46, no. 278 (December 1880): 729–38. ↵

- Samuel D. Warren and Louis D. Brandeis, “The Right to Privacy,” Harvard Law Review 4, no. 5 (December 1890): 196, 217. Legal historian Samantha Barbas has written, “The privacy action was aimed specifically at the press on the theory that printed matter, because of its permanence and mass circulation, could create deep and irreversible harms. Embarrassing facts communicated orally, as chitcat or rumors, would not be legally remediable; spoken gossip, fleeting and transitory, was a familiar albeit annoying aspect of daily life that could be dealt with through extralegal means, or if the comments were especially impertinent, the law of slander.” Samantha Barbas, Laws of Image: Privacy and Publicity in America (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015), 37–38. ↵

- John B. Thompson, Political Scandal: Power and Visibility in the Media Age (Cambridge, England: Polity Press, 2000), 52, 57. See chapters two and three for the development and characteristics of mediated scandal. See also chapter one for an analysis of the relationship between gossip and scandal. On page 27, Thompson notes that in the case of newspaper gossip, “gossip can slide easily into scandal, precisely because the information is made available publicly and can be easily interlaced with opprobrious discourse.” This closer relationship between gossip and scandal in print versus spoken form further emphasizes The Latest Village Scandal’s relationship to the mass media of the Gilded Age. ↵

- Alan Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age (1982; reprint, New York: Hill and Wang, 2007), 123. ↵

- Unidentified undated clipping from New York Herald. Edward Lamson Henry Papers, New York State Museum, Albany (henceforth cited as Henry Papers), H-1940.17.634. ↵

- Charles Johanningsmeier, “The Industrialization and Nationalization of American Periodical Publishing,” in Perspectives on American Book History: Artifacts and Commentary, ed. Scott E. Casper, Joanne D. Chaison, and Jeffrey D. Groves (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press in association with the American Antiquarian Society and The Center for the Book, Library of Congress, 2002), 331. ↵

- James Dabney McCabe, Lights and Shadows of New York Life (Philadelphia: National Publishing Company, 1872), 255; and Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America, 124. ↵

- Mark Twain, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1889), 338. ↵

- D. O. Kellogg, “The Coming Newspaper,” The American 20, no. 522 (August 9, 1890): 329. ↵

- “An Interviewer’s Apology,” The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science, and Art, January 1, 1887, 4. Reprinted as “An Interviewer’s Apology,” The Critic 7 (February 19, 1887): 93. ↵

- See National Academy Notes and Complete Catalogue, Sixty-First Spring Exhibition, National Academy of Design, New York (New York: Cassell, 1886), 18, 39 (cat. no. 434); and Paris Universal Exposition 1889 Official Catalogue of the United States Exhibit (Paris: Charles Noblet et Fils, 1889), 11 (cat. no. 163). ↵

- Catalogue of Modern Paintings, Water Colors, Etchings and Engravings Belonging to the Estate of the Late George I. Seney (New York: The American Art Association, 1894), 34 (cat. no. 87). ↵

- David Flaherty points to other locations where gossip frequently was exchanged in early America, noting that women often stayed at home or met at wells and markets to swap confidences, whereas men gathered in the neighborhood tavern or coffeehouse. Flaherty, Privacy in Colonial New England, 105–6. ↵

- “Old-Time Grist Mills,” Milling 3, no. 3 (August 1893): 232. Reprinted from the New Haven Register. ↵

- Robert H. Thurston, “Modern Uses of the Windmill,” The Engineering Magazine 4, no. 5 (February 1893): 722. ↵

- William Marshall, On the Landed Property of England (London: G. and W. Nicol; G. and J. Robinson; R. Faulder; Longman and Rees; Cadell and Davies; J. Hatchard, 1804), 319. ↵

- Thurston, “Modern Uses of the Windmill,” 719. ↵

- “A Futile Blow,” Harper’s Weekly 28, no. 1454 (November 1, 1884): 717. ↵

- Harriet Beecher Stowe, We and Our Neighbors (New York: J. B. Ford, 1875), 292. ↵

- Warren and Brandeis, “The Right to Privacy,” 196. ↵

- Warren and Brandeis, 196. ↵

- Zukowski, “Edward Lamson Henry,” 168. ↵

- Pamela Fletcher, “Narrative Painting and Visual Gossip at the Early-Twentieth-Century Royal Academy,” Oxford Art Journal 32, no. 2 (June 2009): 249. ↵

- “American Artists,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 6, 1889, 1. ↵

- “A Terrible Tale,” Buffalo Evening Telegraph, July 21, 1884, 1. ↵

- John H. Summers, “What Happened to Sex Scandals? Politics and Peccadilloes, Jefferson to Kennedy,” The Journal of American History 87, no. 3 (December 2000): 833. ↵

- Perhaps feeding Henry’s fascination with scandal was the fact that his family luckily averted it. Citing Henry’s unpublished personal papers in her possession, Kaycee Benton Parra notes that his parents had a “runaway secret marriage . . . considered quite a disgrace” at the time. As a result, their marriage was hidden publicly, and Henry was raised as his mother’s nephew. Henry ensured that biographies of the artist were vague on his upbringing. This “subterfuge” was a success: no ill gossip or scandal on the subject ever touched Henry in the course of his career. See Kaycee Benton Parra, The Works of E. L. Henry: Recollections of a Time Gone By (Shreveport, LA: The R. W. Norton Art Gallery, 1987), 5. This author has found no direct statements by Henry elsewhere on the topics of gossip and scandal. ↵

- McCausland, The Life and Work of Edward Lamson Henry, 54–55. Most of the clippings that survive in Henry’s archive date to the late 1890s and early 1900s. McCausland noted that another two large scrapbooks compiled by Henry were accidentally destroyed shortly after his death. It is not known when exactly Henry began his practice of collecting newspaper clippings. ↵

- Unidentified clippings, Henry Papers, 13.12.33 and H-1940.17.628. The first is dated November 8, 1898, from the New York Herald; the second, on the subject of the Moores’ divorce, is dated May 9, 1902. ↵

- Unidentified clipping, Henry Papers, H-1940.17.873. ↵

- For the historical shift in news reading from a collective ritual to a private one, and for similar renderings of early American newspaper reading, see Thomas C. Leonard, News for All: America’s Coming-of-Age with the Press (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), chapter one. Henry strongly resembles the men who puff on cigars and tilt their chairs backwards in scenes of public news reading like Nicolino Calyo’s watercolor painting Astor House Reading Room (c. 1840; Museum of the City of New York). Leonard notes that European visitors often interpreted these behaviors as a rejection of the aristocratic manners of Europe and an assertion of American independence. Henry’s masquerade performs these patriotic airs and may be interpreted as a flattering self-portrait of the artist as a quintessentially American republican male. ↵

- Rene Bache, “Christmas at Mount Vernon When George Washington was Alive,” New York Herald, December 15, 1901, 4. Henry Papers, H-1940.17.247. ↵

- This article appears on the verso of an illustrated feature on “The Last of the Gouverneur Morris Mansion,” about a historic New York house slated for demolition as the New Haven Railroad expanded. Its author described the home’s deserted halls and silent rooms while sharing “the story of the Morris family of Revolutionary Fame”—this, despite the fact that “for years surviving members of the family, disliking publicity of their affairs, refused inspection of the premises unless visitors came well recommended or really desired to add contributions of value in historical reference to the Morris estate.” “The Last of the Gouverneur Morris Mansion,” New York Herald, June 11, 1905, n.p. Henry Papers, H-1940.17.227O. ↵

- Scott A. Casper, “An Uneasy Marriage of Sentiment and Scholarship: Elizabeth F. Ellet and the Domestic Origins of American Women’s History,” Journal of Women’s History 4, no. 2 (Fall 1992): 10. Casper specifically addresses Ellet’s goals here. See also Susan Reynolds Williams, Alice Morse Earle and the Domestic History of Early America (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013); and Julie Des Jardins, Women and the Historical Enterprise in America: Gender, Race, and the Politics of Memory, 1880–1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.) ↵

- Benjamin Bussey Thatcher, “Thacher’s History of Plymouth,” Christian Examiner 21 (September 1836): 68. Partially quoted in Eileen Ka-May Cheng, The Plain and Noble Garb of Truth: Nationalism and Impartiality in American Historical Writing, 1784–1860 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2008), 79. On page 85, Cheng notes the gendered implications of such language: “The very terms that historical writers used to speak of social history, such as ‘domestic history’ or the ‘gossip of history,’ pointed to the feminine associations of this kind of history. These associations in turn reflected the assumptions of domestic ideology, which identified the private realm with women.” ↵

- Anne Hollingsworth Wharton, Through Colonial Doorways (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1893), 3–4, 10–11. ↵

- Quoted in Don Seitz, Joseph Pulitzer: His Life and Letters (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1924), 422. ↵

- “Through Colonial Doorways,” The Nation 56, no. 1455 (May 18, 1893): 374. ↵

- Wharton, Through Colonial Doorways, 82. ↵

- “Women of the American Revolution,” New York Times, Saturday Review of Books and Art, October 20, 1900, 725. ↵

- “Passes en Passant at Books, Publishers, and Authors,” The XIX Century 2, no. 5 (April 1870): 897. ↵

- For Ellet as a gossip about Poe and Osgood, see John Evangelist Walsh, Plumes in the Dust: The Love Affair of Edgar Allan Poe and Fanny Osgood (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1980); Mary G. De Jong, “Lines from a Partly Published Drama: The Romance of Frances Sargent Osgood and Edgar Allan Poe,” in Patrons and Protégées: Gender, Friendship, and Writing in Nineteenth-Century America, ed. Shirley Marchalonis (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1988), 31–58; and Sidney P. Moss, Poe’s Literary Battles: The Critic in the Context of His Literary Milieu (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1963), 207–21. ↵

- Amy Kurtz Lansing, Historical Fictions: Edward Lamson Henry’s Paintings of Past and Present (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2005), 12. ↵

- Maureen E. Montgomery, Displaying Women: Spectacles of Leisure in Edith Wharton’s New York (New York: Routledge, 1998), 147. Eric Homberer writes similarly, “The growth of interest in society was something of a Faustian bargain for the wealthy.” Many “colluded unashamedly in their heightened visibility. What inevitably followed was the discovery that once journalists had been admitted to a society ball, socialites were captives of the machinery of publicity.” “Scandals became harder to hide” among aristocratic circles, and “(t)he costs of discovery could be high.” Eric Homberger, Mrs. Astor’s New York: Money and Social Power in a Gilded Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 11–12. ↵

- The “400.” (Officially Supervised) (New York: Melville Publishing, 1890), 19, Henry Papers, H-1941.5.4. ↵

- Henry Clews, Twenty-Eight Years in Wall Street (New York: J. S. Ogilvie Publishing, 1887), 164. ↵

- Clews, 164–65. ↵

- “Crash in Wall Street,” New York Herald, May 15, 1884, 5. ↵

- “The Stricken Capitalists,” The Boston Sunday Herald, May 25, 1884, 16. ↵

- “Crash in Wall Street,” 5. ↵

- “Crushed in Wall St.,” New York World (Sunday Edition), May 18, 1884, 1. See also the advertisement for this feature, “Wall Street Celebrities,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 17, 1884, 6. ↵

- “Gossip Concerning Blue Wednesday in Wall Street,” The Boston Sunday Herald, May 18, 1884, 16. ↵

- Clews, Twenty-Eight Years in Wall Street, 165, 167. ↵

- “Crash in Wall Street,” 5. ↵

- “The Stricken Capitalists,” 16. ↵

- The Gossips is illustrated in McCausland, The Life and Work of Edward Lamson Henry, 287 (cat. no. 349). A photograph of The Village Tavern (or Telling of the Latest Sensation) is in the Henry Papers, H-1982.107.4. These canvases belonged to a still-larger subset of Henry’s work that pictured the transmission of the news by way of country folk and their face-to-face encounters. Canvases such as News of the Nomination (1896; Mead Art Museum at Amherst College) and News of the War of 1812 (1913; Private collection) pictured the older patterns of information exchange that prevailed before the rise of the popular press at midcentury supplanted oral news networks with printed ones. For another art-historical perspective on the “transition from communal and artisanal forms of information exchange to increasingly impersonal ones” represented by the commercial press, see Bryan Wolf, “All the World’s a Code: Art and Ideology in Nineteenth-Century American Painting,” Art Journal 44, no. 4 (Winter 1984): 328–37. ↵

- Henry, “A Memorial Sketch,” 339. ↵

About the Author(s): Nicole J. Williams is a PhD Candidate in the Department of the History of Art at Yale University