Virginia Arcadia: The Natural Bridge in American Art

Curated by: Christopher C. Oliver

Exhibition Schedule: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA, February 6–August 1, 2021; Taubman Museum of Art, Roanoke, VA, April 1–August 7, 2022

Exhibition Catalogue: Christopher Oliver, foreword by Alex Nyerges, introduction by Jurretta Jordan Hecksher, Virginia Arcadia: The Natural Bridge in American Art, exh. cat. Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2021. 108 pp; 43 color illus.; 40 b/w illus. Paper: $20.00 (ISBN: 978193431185)

In light of the current environmental crisis and a related focus on ecocritical approaches to art history, several recent exhibitions have reexamined the cultural significance of landscape art in the Americas and its role in shaping and disseminating national mythologies.1 Virginia Arcadia: The Natural Bridge in American Art, featuring more than seventy objects across a range of media—maps, prints, photography, decorative arts, video, and paintings drawn from private collections and museums, including the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA)—continues this trend, tracing the visual history of a Virginia landmark and its place in the construction of America’s cultural identity.

The Natural Bridge, a 215-foot-tall limestone arch located in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, spans a tributary of the James River. It lies within the ancestral lands of the Indigenous Monacan nation, whose members continue to research and preserve the Natural Bridge and its significance in their history. While it is now believed to have been formed by erosion over millions of years, Thomas Jefferson, who purchased the bridge in 1774, speculated that “this most sublime of Nature’s works” was created by “some great convulsion” in the earth’s past.2

At the exhibition’s entry, mural-scale signage features a reproduction of David Johnson’s Natural Bridge, Virginia (1860; Reynolda House Museum of American Art), which immerses visitors in a panoramic view of the arch and the lush forests surrounding it. While a barely visible tavern and roadway hint at the area’s commercialization, these details are minimized by the grand sweep of Johnson’s pastoral vision. His painting, created just prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, envisions the natural world as a place of peace and serenity: the Virginia Arcadia referenced in the exhibition’s title. Soon, however, the Shenandoah became not a site of a harmonious golden age but a pivotal battleground in what Walt Whitman described as a “slaughter-house” of war.3 In ways both obvious and subtle, Virginia Arcadia highlights the malleability of the term “arcadia” and the varied meanings attached to it.

The exhibition is arranged chronologically, with its first section titled “Natural Bridge, Thomas Jefferson, and the Shaping of a National Landscape.” The viewer’s attention is initially drawn to Caleb Boyle’s full-length portrait Thomas Jefferson at Natural Bridge (fig. 1). The newly elected president, dressed in a simple black field coat, walking stick in hand, and framed by the surrounding landscape, is represented as a “natural man” of the Enlightenment who embodies simple republican values and virtues. The first of many responses to Jefferson’s call for American artists to paint the Natural Bridge, Boyle’s portrait reflects its subject’s appreciation for both the arts and America’s scenic wonders as useful tools in the process of nation building. Jefferson also promoted the Natural Bridge in his writings. In Notes on the State of Virginia (1787), for example, he describes it as “so beautiful an arch, so elevated, and springing, as it were, up to heaven.”4

Jefferson considered the Natural Bridge, like Niagara Falls, a monument equal if not superior to those of the Old World. Adjacent to the Boyle portrait, a reproduction of a section of Monticello’s dining room shows how he paired the two American sites visually as well as conceptually, with engravings of each framing a central window (see fig. 1). By coupling these landmarks from the country’s northern and southern regions and according them places of honor in one of his home’s most visible spaces, Jefferson highlighted their role in the shaping of a collective national identity that was rooted in the natural world.

The exhibition contextualizes these images within a selection of early maps and engravings and raises questions about Jefferson’s long association with the Natural Bridge. As a chart and wall text detailing the “Native American Presence” suggest, his 1774 purchase of this land from the Crown was enabled by the ongoing displacement of Virginia’s Native inhabitants. While linked favorably to his national and international status and pivotal role in founding and governing a new republic, Jefferson’s ownership of the bridge would also be identified with his actions regarding westward expansion, Native land rights, federal Indian policy and, as a slaveowner, his role in perpetuating a system he repeatedly decried.5

Like so many of his fellow citizens, Jefferson’s “arcadia” was linked to the American West and the “empire of liberty”—a land of yeoman farmers, rural prosperity, and union without coercion—that he envisioned there.6 Here again, the Natural Bridge was instrumental. The Great Wagon Road, crossing the bridge’s span as it headed southwest from Philadelphia, was an important pathway to early settlement in the West via the Wilderness Road into the Kentucky territory.

The second gallery moves from the early republic to the antebellum period and addresses “Romanticism and the Virginia Landscape.” At midcentury, the Natural Bridge was at the peak of its fame as a national landmark and a subject of art, due in part to Jefferson’s earlier efforts but also to the rise of the Hudson River School and the recognition of landscape as a defining cultural element and preeminent form of national art. Expanding tourism, transportation, and print networks made scenic sites widely accessible, either in person or via printed written and visual materials.

While introducing several lesser-known landscapists, Virginia Arcadia also offers new perspectives on the work of more prominent artists. Edward Hicks, for example, in his Peaceable Kingdom (1822–25; Mead Art Museum, Amherst College), reimagined the concept of arcadia in terms of his Quaker beliefs. He resituated biblical narratives in a New World setting, using the Natural Bridge as the backdrop for the gathering of animals and a “little child” cited in the Book of Isaiah. Hicks also makes the Natural Bridge the imagined setting for a key historical event, the 1682 signing of William Penn’s treaty with the Lenape chiefs (which actually took place in eastern Pennsylvania). Barely visible, the scaled-down Indigenous figures in the background underscore the scarcity of Native Americans in Natural Bridge imagery. In this body of work, the Shenandoah’s first inhabitants are present primarily as an absence that references the trope of “the vanishing American” in literal terms. Recalling Jefferson’s pairing, Hicks’s Falls of Niagara (1825; Metropolitan Museum of Art) hangs beside his Natural Bridge canvas in the exhibition.

Nearby, Frederic Church’s The Natural Bridge, Virginia (1852; Fralin Museum of Art, University of Virginia) likewise references Jefferson’s connection to the site but in a very different manner, underscoring the wide variety of formal, aesthetic, and narrative agendas and strategies represented throughout Virginia Arcadia. Emphasizing the monumental scale and steep vertical ascent of the rock face, Church situates viewers below the arch at relatively close range (a “keyhole” perspective). The dramatic play of light and dark illuminates not only the textures, color contrasts, and ancient striations that mark its craggy surface but also calls attention to two small figures engaged in conversation at its base: a standing man of African descent gesturing upward and a seated white woman. Theirs is the only human presence, a fact remarkable in and of itself, considering the political tensions and racial prohibitions of the era. Further, the African American male figure is placed in a position of authority; he is the teacher, the woman his student. His identity as Patrick Henry, a free Black man hired by Jefferson as caretaker and de facto tour guide at the Natural Bridge, was not known until 2003. Church’s inclusion of Henry underscores the complex place of African Americans in the Natural Bridge story.7

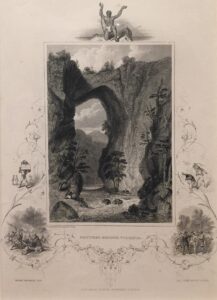

In connecting Jefferson, Henry, and the Natural Bridge, Church overlays the iconography of an American sublime—a focus on the overwhelming power of nature and, as Jefferson recounted in his Notes, the melding of terror and delight that it inspires—with his own antislavery convictions and a belief in landscape as a bearer of social and moral truths. While this idea may be implicit in Church’s canvas, two prints by British engravers J. and F. Tallis render the connection explicit by framing the Virginia State Capitol, designed by Jefferson, and the Natural Bridge with vignettes illustrating the cruelties of slavery (fig. 2). Above the stone arch, a manacled Black man reprises the “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” pose used by British and American abolitionists to raise funds and promote their cause. Hung in close proximity, the painting and prints initiate a powerful conversation about slavery and race, self-evident truths, Jefferson, and the land itself.

This conversation is indirectly referenced in what is arguably the most unusual image in the exhibit: a large panel from the wallpaper series Views of North America by the French firm Zuber et Cie. Again pairing the Natural Bridge and Niagara Falls, the Dance of the American Warriors section of the panel (fig. 3) depicts the bridge primarily as a backdrop for an imaginative mix of social and theatrical performances staged in the foreground. As a stagecoach overflowing with visitors approaches, a group of exoticized Native American “warriors” in generic Orientalist-derived costume converse, drum, and dance for the entertainment of fashionably dressed, mixed-race tourists. Popular in France, England, and the United States, this colorful, lively, and altogether fanciful representation of Jacksonian America as a prosperous, racially integrated society once decorated scores of fashionable homes. Based exclusively on print and literary sources, it appears to imagine a modern New World arcadia grounded in democracy and racial equality.

In keeping with one of the exhibition’s central narratives—the shifting place of the Natural Bridge in the national imaginary—the final section of Virginia Arcadia documents the arch’s post–Civil War identity as a genteel tourist attraction rather than as a national icon. Of particular interest here is a series of photographs by Michael Miley (1841–1918), many of which were printed only after his death. Tightly cropped and shot from unexpected angles, their singular focus on small sections of the bridge’s craggy surface lends them a modern sensibility that is unique in this exhibition.

A generously illustrated catalogue extends Virginia Arcadia’s rich visual content. Curator Christopher Oliver’s thought-provoking essay revisits many ideas and issues raised in the exhibition in greater depth, including an extended discussion of Church’s 1851 trip to Virginia and the on-site drawings he produced there. It also explores a number of topics relevant to but not directly addressed in the exhibition, such as Thomas Cole’s interest in the subject of bridges and archways in relation to the Natural Bridge. An exhibition checklist and select bibliography are included.

Thomas Jefferson’s wish that the Natural Bridge and its environs be preserved as “a public trust” was realized in 2016, when the area became a Virginia state park. While the arch has long been a locus of mythmaking, national aspirations, and contested histories, Virginia Arcadia alerts viewers to the multiplicity of meanings once attached to this natural site and to the concept of classical Arcadia reborn on American soil, prompting a deeper consideration of both. Finally, the exhibition asks: whose Arcadia is represented here; who is included and who is excluded from it; and how are these questions still relevant today?

November 19, 2021: An earlier version of this review misstated the nature of the reproduction of Jefferson’s dining room at Monticello; only a section of it was reproduced in the exhibition.

Cite this article: Debra Hanson, review of Virginia Arcadia: The Natural Bridge in American Art, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12749.

PDF: Hanson, review of Virginia Arcadia

Notes

- Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture (2020–21; Smithsonian Museum of American Art); Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment (2018–19; Princeton University Art Museum, Peabody Essex Museum, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art). ↵

- Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (1787, repr. New York: W. W. Norton, 1972), 24. ↵

- Walt Whitman to Louisa V. V. Whitman, July 7, 1863 in “Life and Letters,” The Walt Whitman Archive, https://whitmanarchive.org/biography/correspondence/tei/loc.00775.html. ↵

- Jefferson, Notes, 25. ↵

- Jefferson, Notes, 162–63. ↵

- “Thomas Jefferson: The West,” online exhibition, Library of Congress, accessed October 21, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffwest.html. ↵

- Henry died in 1831. For a more information on Henry, Church’s 1851 trip to Virginia, and his painting of Natural Bridge, see Christopher Oliver et al., Virginia Arcadia: The Natural Bridge in American Art, exh. cat. (Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2021), 53–63. ↵

About the Author(s): Debra Hanson is an independent scholar and faculty affiliate at Virginia Commonwealth University’s School of the Arts