Visuality and the Plantationocene: The Panoramas of Regina Agu

Passage: the act or process of moving through, under, over, or past something on the way from one place to another; the process of transition from one state to another; a duct, vessel, or other channel in the body; a connecting way; the right to pass through somewhere; the right to travel or leave a place; official approval of something, especially a new law; the act or process of moving forward; the process of time going past.

The Middle Passage: the forced voyage of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the New World.1

In 2019, contemporary artist Regina Agu debuted a site-specific installation called Passage at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA), which took the form of a multilayered photographic panorama that wrapped around the museum’s neoclassical Great Hall (figs. 1 and 2).2 At one hundred feet long, Passage is a digital composite of dozens of semitransparent images documenting multiple sites across the vast network of waterways that surround the city of New Orleans. Traversing the region by boat, Agu turned her lens to a changing, vulnerable ecosystem, where rivers, bayous, marshes, and wetland forests have been irreparably damaged by the petrochemical refineries that have lined the Gulf Coast for over a century, accelerating coastal erosion, saltwater intrusion, and sea-level rise.

There are no human figures to be found in any of the work’s four panels, but the specter of both agricultural and industrial interventions in the landscape is latently palpable, as is their toll on Black, Indigenous, and immigrant communities who live and work along these waterways. The loss of livelihood, land, and even human life in recent decades is implicated in the faint and doubled images of decommissioned refinery equipment, in the rhythmic intrusions of bent rebar and concrete, and in the stilted houses that hover, abandoned, above placid waters. Commissioned to run alongside a concurrent exhibition at NOMA that featured paintings of Louisiana produced during the colonial and antebellum periods, Passage is guided by Agu’s investment in Black geographies. Through this lens, she reveals the contemporary legacy of the establishment of plantation economies in the Americas, which continue to exist in systems of disenfranchisement, environmental racism, incarceration, and other forms of injustice. Agu is also sensitive to the ideological role that images have played in enabling the fulfillment of humankind’s fantasy to possess and cultivate nature, which resonates in her choice to utilize the panorama format, one that is historically affiliated with the scopic regime of imperialism.

While charting Agu’s interests in landscape painting, panoramas, histories of enslavement, and the plantation complex—each marked, in different ways, by their panoptic and carceral geographies—this article asserts that Passage may best be understood in light of Plantationocene discourse. This framework, whose orientation is temporal as much as it is spatial, charts the plantation as a point of origin and acceleration for our current ecological crisis and traces its unequal impact on marginalized populations worldwide. Interweaving reflections on parallel examples in Agu’s oeuvre as well as contemporary art, film, and photography in Louisiana, I suggest that Passage presents Louisiana’s semiliquid landscape in a state of temporal collapse, subverting the stable logic of the picturesque. Documenting sites that are losing land and mappable cohesion at a rate that cannot keep up with cartographic representation, her work imagines a kind of future ruin or, to borrow from the writing of Robert Smithson, a ruin in reverse, wherein the destruction of a landscape is set into motion by its cultivation. Finally, I conclude that the artist’s centering of an aquatic perspective serves as a foil to both the visual and extractive regimes of the plantation—its existence having been dependent on conscripted labor brought across the Atlantic, on irrigation and water-management systems, and on forms of enclosure and spatial fixity that the element of water necessarily resists.

Sea Change (2016): Panoramic Vision and Maritime Cartographies

Although Agu has recently relocated from Houston to Chicago, her work has long been invested in the politics and ecologies of the southeastern United States. In installations utilizing photography, found text, collage, and drawing, her practice examines Black communities’ relationships to landscape, be they political, social, or environmental. Born in Houston to a Nigerian father and a Louisianan mother, Agu is attentive to the maritime routes that mark not only her biography but also broader histories of the Black Atlantic, from the Middle Passage to the rise of petrocultures across the Americas and Africa. She explains, “As I moved back and forth between the Gulf of Mexico and the Gulf of Guinea, in particular, I became very aware of the shared connections of language, culture, and migration, as well as the common legacies of enslavement, colonialism, and economic ties that continue to circulate between these landscapes today.”3

For her breakout exhibition at Houston’s Project Row Houses in 2016, Agu created a site-specific installation titled Sea Change, which positioned the overdeveloped coast of Texas in relation to parallel flows of empire, natural resources, and human cargo across the Atlantic Gulf Stream (figs. 3 and 4).4 The piece took the form of an eighty-foot-long continuous photographic panorama, which was installed along three walls of the gallery, in a shotgun-style house in Houston’s Third Ward. Depicting the shores of Galveston, Texas, Sea Change surveys a landscape formed by artificially constructed sand dunes that line the scenic coastline. In what was popularly known as the “summer of seaweed” in 2014, Galveston’s beaches were inundated by large quantities of red Sargassum algae, which piled up in mounds, producing a rotten stench along the coast.5 Fearing that the invasion would negatively impact the region’s peak tourism months, Galveston city officials hired a team of engineers to bulldoze, remove, or somehow hide the algae in order to counteract what they considered an environmental crisis. The solution that they found was to create a system of artificial dunes that not only visually covered the seaweed but also helped to protect the beaches from future outbreaks and postpone the effects of coastal erosion.

Agu was intrigued to learn that the shores of Mexico, several Caribbean islands, and the coast of West Africa were also invaded by Sargassum algae during these exact same months; the global phenomenon was linked, in part, to changing temperatures across the Atlantic Gulf Stream. These locales are also dependent on tourism, but unlike Texas, their economic resources were insufficient to devise similarly ambitious solutions to the problem. “We have infrastructure to deal with it,” Agu told writer Casey Gregory in 2017, and the event, as Gregory summarized, “revealed inequities at multiple levels in . . . various countries” on either side of the Atlantic.6 As such, Agu’s project drew attention to regional disparities that will continue to intensify as locales face the rising costs of climate change from tropical storms to seaweed invasions, as well as salinity, pollution, and erosion.

Agu is interested in the interconnectedness of regions that are politically distinct, separated and demarcated by national borders, and yet face shared ecological and social conditions that are transoceanic in origin. The historic flows and conditions of imperialism, industrialization, and the modern nation state are, ultimately, linked to bodies of water. The simultaneous appearances of red Sargassum algae in Côte d’Ivoire and Galveston, for instance, is no surprise, given their histories as major ports on either side of the transatlantic slave trade; both coasts are also now lined with oil wells and refineries.

Sargassum algae is so named for the Sargasso Sea—a body of water located within the Atlantic Ocean that is recognizable by the swarms of seaweed that float freely across its surface. The only named sea that is not bordered by any land mass, it is embraced by a swirl of ocean currents that flow in a clockwise direction, from North America to Europe, to Africa, and then westward again toward the Caribbean archipelagos. The Sargasso Sea is mentioned in writings by Christopher Columbus, who crossed its waters on his maiden transatlantic voyage, setting into motion the European colonization of the Americas. This fact is acutely relevant to Agu’s choice of medium for this installation: Sea Change is the artist’s first work to utilize panoramic photography, a format that in many ways embodies the visuality of the nineteenth century and can be contextualized within broader histories of exploration, industrialization, and imperialism.

Circular panoramas and cycloramas, which immerse the viewer fully in painted vistas of exotic landscapes or city skylines glimpsed from rooftops, were popular attractions in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe and the United States (fig. 5). As visual spectacles, they enabled their audiences to experience the illusion of travel and visual command over a landscape. As Katie Trumpener and Tim Barringer note in their recent anthology on the history of panoramas, this quality could lead to the use of such displays “to justify colonial expansion” through the representation of foreign places as “savage” and in need of civilizing reform.7

The panorama extended and adapted many of the ideologies that had become associated with landscape representation in painting and other visual arts. As Denis Cosgrove points out, the invention of paesaggio (landscape) in Italian painting corresponds to the “physical appropriation of space as property, or territory” and accompanies the proliferation of estate charts, cartographic diagrams, and even the use of linear perspective in two-dimensional representations.8 The latter, as a visual device, allows the “sovereign eye” to experience “absolute mastery over space.”9 In turn, landscape representations came to offer a “structuring of the world so that it may be appropriated by a detached, individual spectator to whom an illusion of order and control is offered through the composition of space according to the certainties of geometry.”10

Panoramas introduced the additional effects of the beholder’s own mobility via the body’s perambulation across a viewing platform. It is this quality that led Walter Benjamin to consider motion to be one of the key elements of modernity, as it is fundamental to the panoramic experience.11 Okwui Enwezor writes more critically on the implications of the new senses of mobility and nearness that were provoked in the nineteenth century by factors such as the invention of photography, the panorama, the circulation of ethnographic travelogues, World’s Fairs, and transcontinental railroads, describing the summary effect of these technologies as “intense proximity, a form of disturbing nearness that unsettles as much as it exhilarates, and transforms as much as it disquiets the coordinates of national cultural vectors.”12 Through such transformative apparatuses and effects, modern subjects could be transported—both literally and conceptually—across space and time. Enwezor asks, importantly, “By what right does one travel? And by what authority does one explore?” These activities, he suggests, “form the bookends of colonial modernity’s relationship to the world of the outside.”13 Cognizant of Galveston’s significant role within the histories of both enslavement and liberation politics in the United States—as the location in which emancipation was declared in Texas on Juneteenth, two years after the American government officially outlawed the institution of slavery—Agu positions this coastline simultaneously as a key site within global currents of exploration and colonization, as a palimpsest of Black diasporic histories and narratives, and as a harbinger of the world’s ecological futures.

Landscape Painting in Louisiana

Agu expands on these same issues in her 2019 photographic installation Passage. NOMA commissioned the artist to create a new site-specific work to run concurrently with the exhibition Inventing Acadia: Painting and Place in Louisiana, which charted a history of the region’s representation in landscape painting of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.14 Passage was conceived as a kind of speculative companion to these works, which, in many cases, were commissioned by political authorities or members of Louisiana’s plantocracy to survey and document the landscape as it transformed from an alluvial wilderness to one that was agriculturally productive, cultivated at the hands of enslaved laborers. Given the realities of erasure and violent exploitation that undergird this narrative, the exhibition’s curator, Katie Pfohl, felt that a contemporary artist would be best positioned to augment the critical perspectives offered in the historical exhibition and explore the ways in which these landscape politics linger in the present day.

Inventing Acadia told the story of often-itinerant artists, traveling from Europe or elsewhere in the Americas, whose training in landscape painting was centered on the representation of the rocky woodlands and majestic valleys more characteristic of Western Europe or the northern United States. Positioning Louisiana as a kind of “testing ground” for artistic innovation amid the colonization and eventual modernization of the Gulf Coast, the exhibition charted the work of artists who grappled intensely with the enigmatic ecology of southeast Louisiana, which, in the eighteenth century, as Pfohl describes it, was “a landscape in which it was impossible to fix the boundaries between delta and marsh, swamp and bayou, or river and sea.”15 The set of paintings that first greeted the viewer represent this place as an untamable, watery wilderness; in many works, such as Joseph Rusling Meeker’s The Acadians in the Atchafalaya, “Evangeline” (fig. 6) or Henry Chapman Ford’s Water Lilies and Spanish Moss (1874), the murky light of humid dusks is dramatically refracted through tangled tree roots and lacy veils of Spanish moss. Such images reflect the words of the French geographer Élisée Reclus, who in 1853 described Louisiana as “a vast alluvia in a semi-liquid state.”16 A significant number of the included artists were affiliates of the French Barbizon School, which emphasized the importance of sketching from nature. Their cohort had found inspiration in the royal parklands just outside of Paris, a property that was preserved and protected for the enjoyment of the leisure classes, despite its frequent depiction by artists as rugged wilderness. As Kelly Presutti points out, “Barbizon painters pictured a landscape in the midst of major environmental reform . . . often explicitly respond[ing] to ongoing political and ecological conflicts regarding land and water use management.”17

Likewise, as Pfohl writes, artists who lent representation to swamps and bayous teeming with exotic flora and fauna were also, often, witness to that landscape’s harnessing through “levees and logging, the digging of canals, and the displacement and enslavement of people.” She continues, “[T]hese artworks picture a landscape actively refusing to be reshaped, either by painterly perspective or through land reclamation.”18 The artist Richard Clauge, raised in New Orleans in the early nineteenth century, brought these considerations to sketches of Louisiana’s majestic oaks, emphasizing their tangled root structures as an affirmation of their natural state in the context of forestry efforts that threatened conservation.

Several works in the exhibition attest to the eventual harnessing of Louisiana’s terrain. Marie Adrien Persac’s Bois de Fleche Plantation (1861) is an exemplary case: from a high vantage point we survey an expansive property, demarcated by picket fences that enclose residences and agricultural plots, with crops arranged in neat, productive grids (fig. 7). Citing the genre of the plantation picturesque that is also prominent in contemporaneous representations of Caribbean estates, Anna Arabindan-Kesson and Mia Bagneris explain that such works picture landscape as property, “emphasizing the plantation space as a pristine ‘colonial garden,’ a site of precise colonial—that is white—management and control.”19 As Arabindan-Kesson and Bagneris affirm, “What is being pictured is the regulation of black lives, the brutalization of black bodies, and the theft of black labor for white profit.”20 Through this picturesque mode of representation, the land is “transformed into an object to be consumed and nature ordered into a potential center of resource extraction.”21

For Katherine McKittrick, the plantation—an agricultural unit, historically dependent on enslaved labor and specializing in the cultivation of a single crop for export to European markets—should be understood as the point of origin for a range of complex spatial practices of domination that remain at work in the contemporary United States. Asking, “In what ways are the historical precedents of anti-black violence in the Americas spatial and linked to our present geographical organization?,” she asserts that the rise of the Plantation Complex and its associated systems of labor and capital created “an uneven colonial-racial economy that, while differently articulated across time and place, legalized black servitude while simultaneously sanctioning Black placelessness and constraint.”22 McKittrick’s writing draws out the politics and poetics of Black geographies as sites of both oppression and resistance, explaining that “the structural workings of racism kept black cultures in place and tagged them as placeless,” in ways that resonate with the carceral geographies and labor conditions of the present day.23

Rising and Sinking: Water Histories of New Orleans

Guided by the framework of Black geographies, Agu turned her lens to the contemporary legacies of the exploitative histories that were witnessed by the works in Inventing Acadia. In the summer of 2019, Agu held a residency at A Studio in the Woods, a program affiliated with Tulane University’s Bywater Institute. Aided by local environmental scientists, she explored the Greater New Orleans region by water, traversing the vast web of tributaries, canals, and bayous from Lake Maurepas down to the mouth of the Mississippi River at its confluence with the Gulf of Mexico (fig. 8). Agu, together with Pfohl, sought to revisit the locations that are depicted in the historic paintings in order to take stock of how the region has been shaped by its cultivation centuries ago. However, she found that the sites that were ascribed an Edenic romanticism in paintings by Toussaint Francois Bigot or Joseph Rusling Meeker are now eclipsed by highway overpasses, bridges, and toxic refineries, if they can be located at all.

The first long panel of Passage, situated to the left when entering NOMA, offered multiple views of shallow Gulf waters at the edge of a rocky shoreline (figs. 9 and 10). While unified by a consistent horizon line and clear blue sky, the photographs are nevertheless imperfectly aligned, shifting in scale and perspectival angles. Interrupting the tranquility of the water, we see the repeated echoes of rebar pillars, which rise from the surface with no known purpose, as well as an abandoned house on stilts and an enigmatic cruciform construction.

This panel depicts the levees of the Mississippi River–Gulf Outlet Canal (MRGO), an artificial channel that links the Gulf of Mexico to the five-mile industrial canal bordering New Orleans’s Upper and Lower Ninth Wards. The canal has been decommissioned and permanently closed to maritime traffic since 2009, four years after it suffered multiple levee breaches and engineering failures during Hurricane Katrina.24 It is the source of the catastrophic flooding of the Lower Ninth Ward and the deaths of at least two thousand residents of the Greater New Orleans region, most of them African American, in the wake of the storm. As historian Andy Horowitz chronicles, the canal’s construction in the late 1950s was met with immediate local resistance due to its known high probability of diverting floodwaters into residential neighborhoods across St. Bernard Parish in the event of a “100 year storm”; as early as 1957, a local newspaper claimed that MRGO would undoubtedly “cause the marshland to disappear due to subsidence.”25 Decades later (and just three years before Katrina would make landfall), the New Orleans–based Times-Picayune reported that the canal was essentially “a shotgun pointed straight at New Orleans, should a major hurricane approach from that angle.”26 In light of these histories, Agu’s representation of this site as an enduring, silent witness to the tragedy of Katrina attests to the fact that, as Horowitz puts it, “disasters have histories” and should never be understood as singular events or random acts of nature.27 The makeshift monument that emerges as a doubled image, just left of center in Agu’s panorama, was anonymously built of concrete and bent rebar as a memorial to lives lost amid a catastrophe that was as much human-made as it was environmental (fig. 11).

Horowitz’s study, Katrina: A History, 1915–2015, frames the storm not as a singular ecological occurrence but as a century-long mishandling of infrastructure projects and urban development. The “existential crisis” of sea-level rise and land loss in Louisiana, which has made the region increasingly susceptible to infrastructural failure and life-threatening floods, is the result of corrupt legislation and ill-conceived interventions in the built environment, which unevenly assigned either vulnerability or protection to various districts (predictably, along race- and class-based lines). Katherine McKittrick and Clyde Woods similarly attest that those individuals and families most severely impacted by the storm “were the victims of federal abandonment and centuries of racial segregation” as much as of the hurricane itself.28 The causes of the disaster, they write, should be attributed to “the failure of . . . ineffective, supposedly protective levees and floodwalls established under federal jurisdiction; . . . [and to] dwindling wetlands and barrier islands, which might otherwise have provided a ‘natural defense’ [but were] destroyed by oil, agricultural, and shipping industries.”29 The disproportionate vulnerability of poor communities of color, in other words, is by design, and the blueprint is evident in historically evolving cartographies of racial exclusion, segregation, and environmental racism.

The opposite panel in Passage, which hung to the right when entering NOMA, depicts the confluence of the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico, where the river’s cold, northern freshwater meets the warm saltwater of the Atlantic (fig. 12). This area was once home to wetlands and barrier islands, which have since disappeared at an astonishing rate; a popular statistic, known to all locals in Louisiana, alleges that the state loses a “football field” of coastal land every single hour. In this panoramic panel, evidence of the landscape’s transformation can be felt in the faint presence of a rusted oil-storage tanker, which is perched on the horizon line, near the image’s right edge. The equipment is among a scattering of leftover debris from an inactive refinery, which was closed once it had extracted and depleted the natural resources from the area, its machinery simply left behind to rot in the Gulf (figs. 13 and 14).

The dredging of canals by oil refineries has led to extreme saltwater intrusion from the Gulf into the coastal wetlands, completely eviscerating cypress forests, freshwater marshes, and entire ecosystems for marine species, including the oysters that were traditionally harvested here. While photographing the area, Agu met a group of oyster fishermen, mostly men of color, who live on a narrow sliver of land called Venice—the de facto endpoint of inhabitable space that extends precariously into the Gulf.30 Agu says, the men “shared openly with us about the ways they are struggling to adapt to the changing salinity of the site, caused by fresh water coming in through the Mardi Gras Pass—a natural diversion of water praised by some environmentalists, that is also drastically changing local ecosystems, and people’s way of life.”31 The disappearance of oysters has threatened their livelihood and caused financial strain, worsened by regulatory restrictions that have been put in place by the state in recent decades. Agu’s panel documents a haphazard array of wooden poles that jut out from the water—these are oyster leases, like property lines, marking the boundaries of the waters within which fishermen must pay to harvest following Louisiana’s assumption of state control over coastal areas since the 1980s, a decade that saw a rapid increase in canal construction related to oil and gas drilling in this area. Such regulations have further disenfranchised poor communities of color, who must make a living in a dying ecosystem. In the stories told by these changing and disappearing landscapes, we come to fathom how the central tenets of the plantation—land alienation, labor extraction, and racialized violence—are ongoing, taking new form in the petrocultures that have emerged in the wake of emancipation.

Through Space and Time: Passage, Industry, and the Plantationocene

Agu’s work joins a number of recent projects that connect antebellum histories to the disenfranchising effects of industry across the South. For example, in the opening scene of Alexander Glustrom’s award-winning documentary film Mossville: When Great Trees Fall (2019), audiences are introduced to protagonist Stacey Ryan, the only remaining resident of the titular community in Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana. Founded in 1790, Mossville was later settled by formerly enslaved Black Americans seeking refuge and self-governance; today, it has been overtaken by a sprawling campus of petrochemical plants owned by the South African megacorporation Sasol. We see Ryan wielding an axe as he chops the roots of a felled tree before the picket fence that surrounds his modest property. His voiceover is interspersed with images of detritus and abandoned signs of human life; these include a wall bearing a hand-painted mural of an abstracted genealogical map, in which a network of arteries snake through a map of continental Africa. Within a few seconds, our vantage point rises to glimpse the world beyond Ryan’s trailer and pickup truck: overturned dirt and grids of industrial roads and power lines eventually lead our gaze to a petrochemical skyline, revealing that his home is trapped within the property of an enormous refinery, which surrounds it on all sides (fig. 15). Ominous clouds of toxic gas paint the sky in chemical hues, ironically reminiscent of the palette chosen by landscape painters, centuries prior, to represent the haunting ambience of the region’s swamplands. Set against the repetitive sound of Ryan’s axe, the panoramic shot makes a clear and undeniable connection between histories of plantation agriculture and conscripted labor, showing how historic forces of oppression are today extended through the effect of contemporary industry on the lives and health of descendants of the enslaved. Indeed, visual parallels can be drawn between the film still of the petrochemical complex and Persac’s painting of the Bois de Fleche Plantation included in Inventing Acadia; in both images, our eye follows a grid of neat orthogonal rows—formed alternately by access roads or picket fences—toward an array of refinery towers in Mossville or toward the plantation’s “big house.”

In recent years, the term Anthropocene has been associated with the theory that we are living in a geological age when human activity and increasing proximity, especially since the Industrial Revolution, are the predominant factors influencing climate and the environment. Yet, as Donna Haraway and others have more recently pointed out, while the Anthropocene is a concept that allows us to speak in simple terms about the human impact on the planet, we must recognize as well that these effects “are not experienced uniformly across the surface of the . . . earth.”32 T. J. Demos has likewise ventured in his book Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today that the “universalizing discourse” of the Anthropocene “avoids the politicization of ecology that could likewise lead to the practice of climate justice” and disavows the “differentiated responsibility (and the differently located effects) for the geological changes it designates.”33

In a published roundtable conversation among anthropologists working on this issue, Anna Tsing elaborates that our focus should rest not on humankind, in its entirety, but on a specific conception of man “invented by Enlightenment thought and brought into being by modernization and state regulation. . . . It is this man who can be said to have made the mess of the contemporary world. It was this ‘man’ who was supposed to conquer nature.”34 For geographer Kenneth Olwig, one of the primary spatial forms that characterize this conquest is that of the enclosure, which, he explains, “is essentially a way of putting a Euclidian grid on the world,” thus forming “the basis of . . . property.”35 While the extraction of fossil fuels is a major factor in the acceleration of global warming, Haraway locates a deeper point of origin for contemporary crises: “We are looking at slave agriculture, not coal . . . as a key transition. . . . [T]he transportation [and alienation] of breeding plants and animals, including people, is crucial to the plantation.”36 The Plantationocene, as this theory has come to be called, locates the origins of industrial extraction in the Middle Passage, in the removal of human labor from one continent to another, and in the establishment of monocultures in colonial landscapes that have disrupted natural ecological systems. All of this is at stake in Agu’s documentation of oyster leases, those arbitrary property enclosures that restrict Black American communities’ ability to earn a living harvesting a marine species that petrochemical refineries have endangered.

The entanglement of spatial and temporal frameworks inherent to the Plantationocene is useful, for me, in parsing the conceptual duality that seems inherent in the formalism of Passage, which, on one hand, reflects on the historical connections between plantations, refineries, and other forms of enclosure but, on the other, resists a replication of their visual logic. Rather than deploying a Euclidian space—one that is rooted in Enlightenment visuality and reflects a desire for mastery and control over nature—Agu’s work is spatially unfixed, disorienting, and difficult to occupy. We are confronted, at eye level, with flooded landscapes wherein the only remains of human infrastructure are makeshift memorials, decaying machinery, and abandoned edifices. This fact produces an unsettling sensation reminiscent of other works by contemporary artists who tackle environmental issues in the region, such as the New Orleans–based artist Dawn Dedeaux’s Water Markers series (fig. 16). Her Plexiglas monoliths bear photographic transfers depicting water, which rises to heights that correspond with flood levels measured after Hurricane Katrina in various parts of the city, where the receding water left a faint discoloration on the walls of homes and businesses. The series is relatively abstract—thus resisting the disaster trope so evident in post-Katrina reportage—but, at the same time, it draws associations between quantifiable flood levels and individual experiences of loss or embodied memory. The works’ anecdotal subtitles—such as Nearly Eight Feet of Water, It Topped Over Seven and Had Over Five—are drawn from newspaper and firsthand accounts of heights that the waters reached within a hundred-mile radius of Dedeaux’s home.

While Agu’s use of a consistent horizon gives the panels of Passage a false sense of cohesion from a distance, on closer inspection we fully realize their composite nature, as layered images pull our gaze in multiple directions, disorienting us, and giving us no clear sense of our bodies’ relative position in relation to the depicted vista. At the same time, the work differs from the most typical format of historic panoramas in that it is not as fully immersive as the nineteenth-century spectacles, for which entire buildings were often constructed and outfitted with illusionary effects. Passage forces our awareness of the vulnerability of the landscape that surrounds NOMA in New Orleans’s City Park, which sits on the site of a former sugar plantation. In Passage, we are essentially left adrift in the depicted landscape, of and in the site we occupy as visitors, disoriented in a kind of Plantationocene aftermath.

In its compositional fragmentation and pictorial opacity, Passage finds resonance with another work in the artist’s oeuvre from 2017, which utilized panoramic imagery in order to explore issues of overdevelopment in Houston: prints 01 and 02 from the digital photo series Drape Panorama (figs. 17 and 18). These works’ compositional format and material apparatus, in which they are mounted at the edges of deep wooden frames, mirror that of nineteenth-century panoramic photographs, wherein individual images, shot along a single horizon line, would be laid out side by side to create the illusion of a seamless vista. Agu’s work depicts scaffoldings, tarps, and construction drop cloths, which characterize the urban landscape in gentrifying neighborhoods across the city. Closely cropped and shot from street level, the images obscure any legibility of place, fixing our eye, instead, on the materials that wrap and abstract the edifices of luxury apartment buildings.

Indeed, issues surrounding urban development and renewal projects—and their often disenfranchising effects on communities of color—informed Agu’s decision to print her earlier work Sea Change on billboard vinyl, a material that is symbolic of the postwar construction of America’s highway system (see figs. 3 and 4). In the 1950s and ’60s, newly constructed roadways cut across the landscape and quickly became the dominant means of traversing and beholding the vastness of America. At the same time, bridges and highway overpasses were frequently mapped across communities of color, disrupting and devaluing such neighborhoods in cities across the country. Sea Change addresses such negative impacts that have accompanied narratives of progress, industrialization, and modernity. Yet, while that work featured a continuous photographic image, the Drape Panorama works are visually disjointed. Markedly rhythmic and haptic in nature, the images focus on the surfaces of undulating tarps, forging a new visual language for the representation of contemporary “landscape” in the United States—one that is supplanted by an aesthetic of transience, demolition, and flux.

As in Drape Panorama, Passage seems to provoke a kind of anxiety in its unstable temporal positions, as if we are glimpsing the future as an already-realized past, looking back on a time when Louisiana had become uninhabitable. This slippage of time is in opposition to circular panoramas, which offered a fixed and more comforting image of the past—whether of ancient battlegrounds or the scenic ruins of Rome or Machu Picchu. When we survey the works’ multilayered depictions of crumbling machinery and abandoned buildings, we seem to be glimpsing our past as a kind of future in the making, with focus on the cultivation of the land as a force in its destruction, as the Plantationocene implies.

This uncanny revelation is also palpable in the photography of Houma artist and activist Monique Verdin, whose intimate portraits of family members taken over the last two decades would become the sole documentation of places that are gradually becoming absorbed by the Gulf of Mexico as sea levels rise (fig. 19). Indeed, the same era of European colonization that saw the Louisiana landscape harnessed for agricultural productivity also witnessed the violent displacement of Indigenous communities. Following the Seven Years’ War, for instance, the French sold off the ancestral land of the Houma people. Forced to migrate southward, the Houma settled in what are now the coastal parishes of St. Bernard, Terrebonne, and Lafouche. A descendent from these communities, Verdin grew up near Bayou Terre aux Boeufs—a region that was once home to prairies and forests that, as she writes, “were clear-cut for plantations to cultivate indigo, cotton, and sugarcane, and manmade levees were constructed along the river to protect these crops from floodwaters.”37 The levees burst in 1922, flooding homesteads all across the coastal parishes; in 1928, when the Mississippi River rose to worrying heights, the parish’s remaining levees were blasted with dynamite to prevent New Orleans from flooding. Members of these and nearby communities are today among the first refugees of climate change. Isle de Jean Charles, which has also become home to the Biloxi-Chitimacha and Choctaw tribes, has lost 98 percent of its land since 1955, as a result of rising sea levels and coastal erosion wrought by, among other factors, the dredging of canals for offshore drilling.38

One of the most prominent visual activists working around issues of environmental crisis, displacement, and cultural loss in New Orleans today, Verdin creates photographs and films that offer intimate stories of life and loss along a disappearing coastline. As Rickard points out, reflecting on an exhibition of Verdin’s photographs for the triennial exhibition Prospect New Orleans’s fourth edition, “The land where [the artist’s grandmother] had picked pecans as a girl is now open water where Monique’s cousins fish for crabs.”39 Across her images, neglected homes and hand-painted signs populate environments in which water and land become indistinguishable from one another, and children navigate streets by rowboat and balance atop partially submerged tree branches that lie scattered across flooded lawns.

Future Ruins and Futurist Revisions

If Passage can be understood as both analogous to, and intervening in, the artistic travelogues of panoramists or antebellum paintings produced as acts of surveillance and exploration, another example from American art history may serve as a useful interlocutor within the trajectory of industrialization. In 1967, amid the construction of the nation’s highway system and urban renewal initiatives, the artist Robert Smithson produced his Monuments of Passaic, a photo essay and mock-travelogue, treating the reader to a sarcastically banal grand tour of New Jersey’s unremarkable wastelands: the monuments are drainage pipes, mounds of dirt, and steel bridges (figs. 20 and 21). Smithson refers to this landscape as a zero-panorama, as “the opposite of the romantic ruin, because the buildings don’t fall into ruin after they are built but rather rise into ruin before they are built.”40 The article and photographs together invite comparison to the grant, expeditionary literature of the nineteenth century, when settler colonists viewed the nation’s landscape as an expansive wilderness (available to us, variously, either to conserve or to render economically productive); yet Smithson pictures it as entropic, suggesting that to construct and industrialize is to simultaneously destroy.

As Jennifer Roberts suggests, this work not only constitutes an ironic play on the grandeur of traditional civic monuments but is also a thesis on the very nature of time and history. She writes that Smithson’s compositions replicate the scattered fields of Mannerist perspectival studies, wherein “oblique forms appear as fallen, wasted views,” pictured flatly from multiple angles.41 The shape of time, for the artist, is less a model of succession—wherein time flies or passes—than one of infinite accumulation. Like Mannerist drawings, these views of Passaic are deposits, infinite pileups of momentary glimpses, eschewing the authoritative gaze of one-point perspective. Roberts observes that “every glance [is] preserved intact, and piled upon the previous in an infinite photosculptural rubble.”42 (This phrasing both mirrors and departs from the earliest descriptions of panoramas; Barringer summarizes the panoramist Robert Barker’s promotion of the genre as “as a revelatory series of glimpses, disjointed yet cumulatively coherent.”43) Spatially and historically unfixed, Smithson’s skewed compositional logic “lends his view of Passaic its bleak and brittle sense of history.” The photographs “preclude memory even as they preserve it. . . . [They] do not remember Passaic so much as bury Passaic under an infinite deposition of mnemonic artifacts.”44 Smithson’s theorization of ruins-in-reverse further addresses the irony of renewal and preservation efforts that, in fact, accelerate the entropic destruction of the landscape, a theme that is subtly embedded in the exhibition narrative of Inventing Acadia as well.

Such descriptions suit Agu’s layered accumulation of photographs depicting the ill-fated waterways of the Gulf Coast. Bringing Smithson’s accumulative view of history into the domain of capitalism’s racial violence, Black geographies, and contemporary climate crisis, her panoramas are guided by a Plantationocene visuality, whose spatial logic, rather than reflecting the fixed Euclidian enclosures of the plantation and associated representational models, is instead brought into a dimension that supersedes space and time. Passage thus responds not only to the history and continuation of the plantation complex in Louisiana but to all interventions that have followed since then and will still come—levees and river management systems, highway overpasses that eviscerate Black neighborhoods, the endangerment of Black livelihoods and Indigenous homelands. Through the layering of directionless vistas of flooded, unpeopled landscapes, the semitransparent debris of construction and decay in Passage offers us a final grand tour of a landscape that is both disappearing and subsuming us: one last passage across future, present, and past temporal ruins.

At the same time, Agu’s harnessing of an aquatic perspective in her articulation of diaspora histories and narratives may serve to negate visual regimes that promise knowledge acquisition through practices of measurement and mapping. As McKittrick reminds us, “That which, and those who, no one knows might also be a map towards a new or different perspective on the production of space,” an alternate episteme wherein the “oceanic history of diaspora” is a foil to “coloniality’s persistence.” Such narratives, she writes, “need to be taken seriously because they reconfigure classificatory spatial practices”—like the plantation paintings on view in Inventing Acadia.45

Examples include the myth of Drexciya, imagined and articulated throughout the liner notes and lyrics of an electronic music outfit of that name based in Detroit. Drexciya, the artist duo, was active in the early 1990s, and as artist and writer Ayeesha Hameed describes it, the myth that they invented describes “a story where the children born of pregnant slaves thrown overboard were able to adapt to living underwater as they went straight from living in amniotic fluid to ocean water, and so built a Black Atlantis called Drexciya.”46 This narrative has gained interest and begun to feature prominently in work by Black and diasporic contemporary artists in recent years, from Ellen Gallagher’s series of paintings Watery Ecstatic (2001–present) to the Otolith Group’s immersive film Hydra Decapita (2010), which connects the futurist narrative of Drexciya to J. M. W. Turner’s tragic painting of the slave ship Zong, titled Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying (1775–1851). It also resonates with the recent work of New Orleans–based artist Katrina Andry, whose series of woodcut prints with holographic mylar transfers, titled The Promise of the Rainbow Never Came, pictures Black figures—adults and infants—thrown into the sea; their human bodies transform into eels and fish as they cross the water’s threshold (figs. 22 and 23). Shown in 2019 at the Louisiana State University Museum of Art, this series “considers the promise of the rainbow—the promise not to be destroyed again by water—unfulfilled for people of color who continue to endure violence and erasure three hundred years after the initial journey toward enslavement.”47

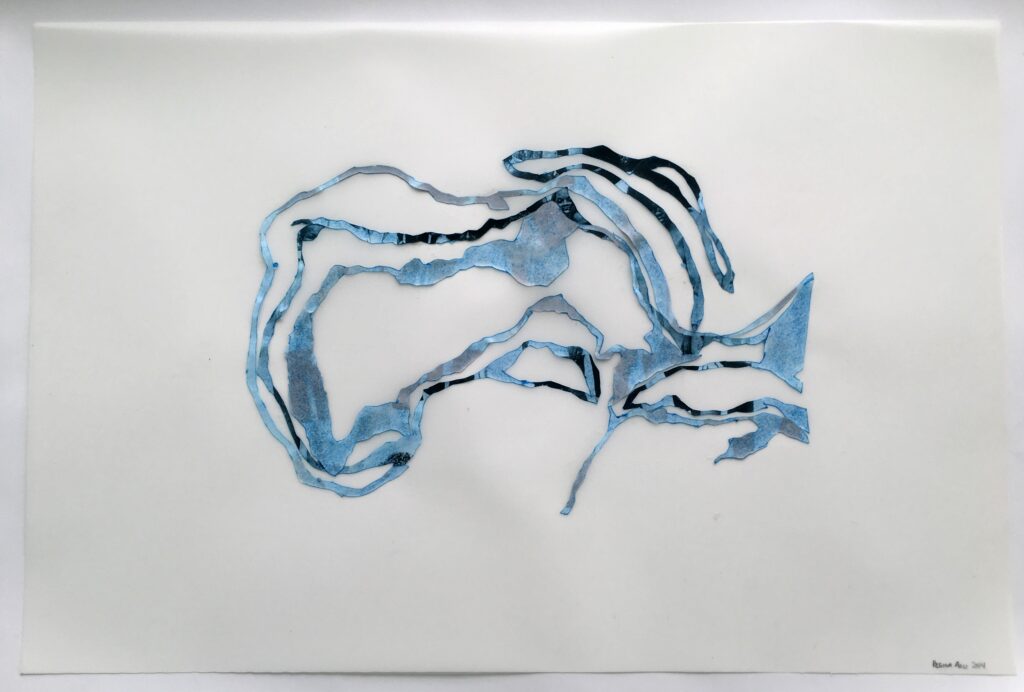

A number of other works in Agu’s oeuvre have addressed oceanic or watery narratives of Louisiana, the region to which she can trace her own maternal lineage, as a site of artistic inquiry. In her ongoing experimental short film Louisiana Water (fig. 24), she collaborated with anthropologist Hadeel Assali, whose Palestinian father also immigrated to Louisiana, to create a poetic reflection on migration, family history, and geopolitical intersections. The piece features small vignettes of performances shot along the Louisiana coastline. In her series Gulf Water (figs. 25 and 26), Agu renders the meandering flows of water as an abstracted collage into which archival portrait photographs are delicately embedded; blurred faces seem to rise and recede at the surfaces of winding, aquatic shapes. One is reminded of Elizabeth Deloughrey’s meditation on Atlantic modernity and the “heavy waters” of transoceanic histories; Deloughrey invokes the words of Gaston Bachelard, who writes that water “remembers the dead.”48

For Hameed, such narratives encapsulate the tension between divergent temporalities of the ocean: first, the near stasis of geological time; second, the “social and economic changes that take place over centuries,” and third, the “shortest measure . . . of events and people—the time of surfaces.”49 As she explains, Drexciya’s mythic power is in “its temporal proposition,” that is “to see time and history as equally in flux as the lapping ocean.”50

As Hameed puts it, the “afterlife” of the Middle Passage is “our present moment.” Water holds memory; it resists time and historicity; it will render porous even the most rigid of enclosures. Agu’s Passage reveals neither a stable and fixed destination nor an obtainable and conquerable history but rather a past and a future, layered and opaque, a speculative grand tour of a place that continues to resist any attempts to map it, a place that is disappearing and subsuming us as we speak.

Cite this article: Allison K. Young, “Visuality and the Plantationocene: The Panoramas of Regina Agu,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12985.

PDF: Young, Visuality and the Plantationocene

Notes

I would like to disclose prior employment as Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellow for Modern and Contemporary Art at the New Orleans Museum of Art from 2017 to 2019, preceding the finalization of the exhibition Regina Agu: Passage but overlapping with the early stages of its preparation. I was not a primary curator for this exhibition and did not undertake in its research directly, but I do know the artist and curator personally and acknowledge that their work has informed this research. I published an early, short reflection on Regina Agu’s Sea Change in the International Review of African American Art (Vol. 29, No. 4, 2020), guest edited by Eddie Chambers. Finally, a preliminary version of this article was presented at the Association for Art Historians conference in April 2021, in a panel entitled “The Plantation Complex” chaired by Drs. Anna Arabindan-Kesson and Emilia Terracciano. I would like to thank the panel chairs for their insightful comments and for the opportunity to share this research at an early stage.

- Definitions are compiled, and at times lightly adapted or re-ordered, from the following online sources: Oxford Languages, Oxford University Press via Google; Cambridge Online Dictionary; Lexico, powered by Oxford; and Encyclopaedia Britannica. All accessed online as of December 2021. ↵

- Regina Agu: Passage was on view at the New Orleans Museum of Art November 2, 2019–February 9, 2020 ↵

- Agu, quoted in “Acadia Revisited, Regina Agu in conversation with Ryan N. Dennis,” in Inventing Acadia: Painting and Place in Louisiana, ed. Katie A. Pfohl (New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art, and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 138. ↵

- Sea Change was on view at Project Row Houses, Houston, TX, as part of Round 45: Local Impact, October 22, 2016–February 12, 2017. For a comprehensive discussion of this work, see also Allison Young, “Between Two Gulfs: Ecological Politics and Black Geographies in the Work of Regina Agu,” in “Black Atlantic Dialogues,” ed. Eddie Chambers, special issue, International Review of African American Art, 29, no. 4 (March 2020): 27–33 ↵

- There was extensive local coverage of the so-called summer of seaweed in 2014. See, for example, Davis Land, “Galveston Researchers and the French Government Have a Question: What to Do About Sargassum?,” Houston Public Media, January 22, 2018, https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/news/2018/01/22/262713/galveston-researchers-and-the-french-government-have-a-question-what-to-do-about-sargassum. Agu discusses the work in Casey Gregory, “Texas Studio: Regina Agu,” Arts and Culture Texas, May 19, 2017, http://artsandculturetx.com/texas-studio-regina-agu. ↵

- Gregory, “Texas Studio.” ↵

- Katie Trumpener and Tim Barringer, introduction to On the Viewing Platform: The Panorama Between Canvas and Screen (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 26. The present article engages mainly with the format of static, while immersive, circular panoramas as a point of reference, rather than moving panoramas, which unscrolled in motion before the viewer’s eyes. For an in-depth study of the latter, see Erkki Huhtamo, Illusions in Motion: Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013). ↵

- Denis Cosgrove, “Prospect, Perspective, and the Evolution of the Landscape Idea,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 10, no. 1 (1985): 55. ↵

- Cosgrove, “Prospect, Perspective, and the Evolution of the Landscape Idea,” 48. ↵

- Cosgrove, “Prospect, Perspective, and the Evolution of the Landscape Idea,” 55. ↵

- Trumpener and Barringer (introduction to On the Viewing Platform, esp. 13) cite the discussion of panoramas that is central to Walter Benjamin’s The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999). ↵

- This concept is developed by Enwezor on the occasion of his exhibition presented at the Palais de Tokyo at the Paris Triennial, April 20–August 26, 2012. See Okwui Enwezor, “Intense Proximity: Concerning the Disappearance of Distance,” in Intense Proximity: An Anthology of the Near and Far, ed. Mélanie Bouteloup and Okwui Enwezor (Paris: Centre national des arts plastiques Tour Atlantique, Artlys, 2012), 22. ↵

- Enwezor, “Intense Proximity,” 20. ↵

- This show ran November 16, 2019–January 26, 2020. ↵

- Katie Pfohl, “In Land, Sea: Louisiana’s Shifting Landscape,” in Pfohl, Inventing Acadia, 21. ↵

- Élisée Reclus, quoted in Pfohl, “In Land, Sea,” 21. ↵

- Kelly Presutti, “Barbizon in New Orleans: Richard Clague’s Site-Specific Practice,” in Pfohl, Inventing Acadia, 60. ↵

- Pfohl, “In Land, Sea,” 22. ↵

- Anna Arabindan-Kesson and Mia L. Bagneris, “The Spirit of Louisiana: Painting Racialised Geographies in the Slave-Holding Atlantic,” in Pfohl, Inventing Acadia, 92. ↵

- Arabindan-Kesson and Bagneris, “Spirit of Louisiana,” 93. ↵

- Arabindan-Kesson and Bagneris, “Spirit of Louisiana,” 87. On this subject, the authors also cite Jill H. Casid’s important study Sowing Empire: Landscape and Colonization (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2005) as a resource for further reading. ↵

- Katherine McKittrick, “On Plantations, Prisons, and a Black Sense of Place,” Social & Cultural Geography 12, no. 8 (2011): 948. ↵

- McKittrick, “On Plantations, Prisons, and a Black Sense of Place,” 949. In Louisiana, this connection is made most saliently in the example of the Louisiana State Penitentiary, commonly called “Angola” after the former plantation on which the maximum-security prison is sited. ↵

- See “MRGO—Mississippi River Gulf Outlet,” Science for Our Coast—Pontchartrain Conservancy, accessed March 2021, https://scienceforourcoast.org/pc-programs/coastal/coastal-projects/mrgo-mississippi-river-gulf-outlet. ↵

- Andy Horowitz, Katrina: A History, 1914–2015 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), 83. ↵

- Horowitz, Katrina, 96. The article cited is John McQuaid and Mark Schleifstein, “Evolving Danger,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 23, 2002, J12. ↵

- Horowitz, Katrina, 6. ↵

- Katherine McKittrick and Clyde Woods, “No One Knows the Mysteries at the Bottom of the Ocean,” in Black Geographies and the Politics of Place, edited by Katherine McKittrick and Clyde Woods (Toronto: Between the Lines; Cambridge: Sound End Press, 2007), 1. ↵

- McKittrick and Woods, “No One Knows the Mysteries at the Bottom of the Ocean,” 1. ↵

- Agu, in discussion with the author, November 2020. ↵

- Agu, quoted in “Acadia Revisited,” 145. ↵

- Kenneth Olwig, quoted in Donna Haraway et al., “Anthropologists Are Talking—About the Anthropocene,” Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 81, no. 3 (2016): 540. See also Haraway, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin,” Environmental Humanities 6 (2015): 159–65. ↵

- T. J. Demos, Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and the Environment Today (London: Sternberg Press, 2017), 21. ↵

- Anna Tsing, quoted in Haraway et al., “Anthropologists Are Talking,” 541. ↵

- Kenneth Olwig, quoted in Haraway et al., “Anthropologists Are Talking,” 557. ↵

- Haraway, quoted in Haraway et al., “Anthropologists Are Talking,” 555. ↵

- Monique Verdin, “Treading Water: A Local Reflects on St. Bernard Parish’s Generations-long Struggle to Stay Afloat,” 64 Parishes, Spring 2019, https://64parishes.org/treading-water. ↵

- See Carolyn van Houten, “The First Official Climate Refugees in the U.S. Race Against Time,” National Geographic, May 26, 2016; Robynne Boyd, “The People of the Isle de Jean Charles Are Louisiana’s First Climate Refugees—But They Won’t Be the Last,” Natural Resources Defense Council, September 23, 2019, https://www.nrdc.org/stories/people-isle-jean-charles-are-louisianas-first-climate-refugees-they-wont-be-last. ↵

- Mary Rickard, “Monique Verdin’s Prospect 4 exhibit,” Via NOLA Vie, February 15, 2018, https://www.vianolavie.org/2018/02/15/monique-verdins-prospect-4-exhibit-shows-how-land-loss-is-always-personal. ↵

- Robert Smithson, “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey,” Artforum (December 1967): 52–57. ↵

- Jennifer L. Roberts, Mirror-Travels: Robert Smithson and History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 76. ↵

- Roberts, Mirror-Travels, 79. ↵

- Trumpener and Barringer, introduction to On the Viewing Platform, 10. ↵

- Roberts, Mirror-Travels, 79. ↵

- McKittrick and Woods, “No One Knows the Mysteries at the Bottom of the Ocean,” 5. ↵

- Ayeesha Hameed, “Black Atlantis,” in FORENSIS: The Architecture of Public Truth, ed. Eyal Weizman (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014), 713. ↵

- Exhibition statement, Katrina Andry: The Promise of the Rainbow Never Came, on view November 15, 2018–March 25, 2019, Louisiana State University Museum of Art, https://www.lsumoa.org/katrina-andry. ↵

- Elizabeth Deloughry, “Heavy Waters: Waste and Atlantic Modernity,” PMLA 125, no. 3 (May 2010): 704. Deloughry cites Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter, trans. Edith R. Farrell (Dallas: Pegasus Foundation, 1983). ↵

- Hameed, “Black Atlantis,” 713. ↵

- Hameed, “Black Atlantis,” 714. ↵

About the Author(s): Allison K. Young is Assistant Professor of Art History at Louisiana State University.